Long before Wisconsin became a geopolitical entity or even a glimmer in the minds of European cartographers, it was shaped—both geologically and spiritually—by the passage of ice. The glaciers that scraped across its bedrock left behind more than just kettles and moraines; they sculpted a terrain that Indigenous peoples would later mark with visual forms of memory and belief. Among the earliest and most enigmatic of these marks are the effigy mounds—earthworks in the shapes of birds, bears, panthers, and serpents—created by cultures who lived in the region between roughly 700 and 1200 AD. These mounds are not merely burial sites or topographic anomalies. They are early, large-scale interventions in the landscape, blending spiritual function with formal composition. In them, one finds a fusion of ecology and cosmology, rendered not on canvas but in earth itself.

The visual language of the effigy mound builders, part of what archaeologists call the Late Woodland culture, is not preserved in pigment or stone but in topographic gesture. Their art moved horizontally across the ground rather than vertically across walls. These constructions—carefully contoured to align with natural ridgelines or water sources—suggest a cultural aesthetic attuned to scale, symbolism, and relationship with the land. In effect, they were shaping both what could be seen and how it would be seen, from above or from the approach.

Petroglyphs and pictographs, found in sites like Roche-a-Cri and the Driftless Area, offer a more directly legible counterpart to the abstract forms of the mounds. These carved or painted images—deer, handprints, abstract forms—emerge from sandstone outcrops and cave walls, frequently positioned near seasonal migratory paths or ritual gathering points. Though fewer in number than in the Southwest or Plains, Wisconsin’s rock art provides rare glimpses into ancient symbolic systems. The visual conventions—simple outlines, repeated motifs, spatial balance—suggest the presence of an aesthetic code: neither wholly decorative nor purely documentary, but a system of signs rooted in belief.

The influence of landscape on pre-contact visual culture

The scale and subtlety of these early forms of visual culture reflect the peculiar geography of Wisconsin—a state divided by water, forest, plain, and bluff. The cultural production of the Indigenous peoples here was inevitably shaped by seasonal rhythms and resource cycles. Visual art did not exist in isolation, as in the Western studio model, but as part of a larger cultural matrix: ceremony, sustenance, migration. The land was not a backdrop for human action; it was a living participant in the composition.

This deeply embedded environmental orientation is echoed in the materials used for adornment, ritual, and trade. Shell gorgets, copper amulets, intricately carved bone tools—many of these objects were not merely utilitarian, but richly symbolic. The Mississippian influence, which filtered northward from Cahokia through the river networks, brought with it a more codified visual grammar, including symmetrical patterns, anthropomorphic deities, and motifs linked to fertility, war, and cosmology. Yet in Wisconsin, these motifs were reinterpreted in localized forms—less monumental than at Cahokia, but no less potent.

An illustrative example is the birdman motif, a figure straddling the human and avian worlds, found on copper artifacts and engraved stones in the Upper Midwest. In Wisconsin, this symbol is often more abstracted, rendered through simpler shapes and more organic integration with natural surfaces. The local variant emphasizes motion and transformation over dominance or hierarchy, reflecting perhaps a different cosmological orientation than in its southern counterparts.

Three particularly vivid glimpses into this pre-contact visual world include:

- A copper crescent discovered near Lake Winnebago, etched with abstract wave patterns and believed to be worn in ritual contexts.

- A sandstone cliff face in Grant County showing overlapping deer and handprints, their layering suggesting both spiritual continuity and ancestral presence.

- A bear-shaped mound in Dane County, whose size and placement mirror both hunting paths and celestial alignments.

These artifacts do not cohere into a single “style” in the art-historical sense. Instead, they suggest a regional sensibility—one defined by adaptation, symbolism, and reverence for the non-human world.

Reconstructing vanished traditions through fragment and echo

Most of Wisconsin’s early visual culture was never meant to be preserved in the museum sense. Created in biodegradable materials—wood, fiber, hide—it vanished with time, leaving archaeologists and historians to reconstruct cultural meaning through fragment and echo. This has often meant reading backwards from later traditions: studying the beadwork, birchbark scrolls, and quillwork of 18th and 19th century Ojibwe and Ho-Chunk communities to hypothesize what came before.

But the danger of backward reading is that it can impose a linear narrative where none existed. Much of the visual tradition in early Wisconsin was non-linear, rooted in cycles and recurrences. The Anishinaabe notion of time as a spiral rather than a line finds a visual analogy in the recurring motifs of stars, animals, and seasonal symbols across multiple art forms.

The transition from sacred landscape to documented artifact—from mound to map, from cliff painting to catalogue entry—mirrors the larger shifts that would come with colonization. By the 17th century, the arrival of French explorers and Jesuit missionaries brought new visual forms and new conceptions of representation. European drawings of Native people, and later Native adaptations of European forms, marked the beginning of a visual hybridity that would shape the next several centuries.

Still, the older, less tangible aesthetics never disappeared. One sees their echo in the way Native Wisconsin artists today—like contemporary Ho-Chunk photographer Tom Jones or Ojibwe painter Rabbett Before Horses Strickland—return to ancestral symbols, materials, and spatial relationships. Their work does not merely revive the past; it continues a tradition of visual thought shaped by water, wood, and sky.

Wisconsin’s earliest art was not made to be hung, sold, or displayed. It was woven into the rhythms of snowmelt, migration, and dream. And yet it endures—not in permanence, but in placement, gesture, and return.

Immigrant Imprints: European Folk Arts in the Upper Midwest

Norwegian rosemaling, Polish wycinanki, and German fraktur

When settlers began arriving in Wisconsin in large numbers in the mid-19th century, they brought not only tools and seeds but also visual traditions honed over centuries in European villages. These weren’t “artists” in the modern sense, nor were they artisans simply replicating heritage. They were farmers, blacksmiths, bakers, and housewives who made art to dignify the rhythms of domestic and spiritual life. Their expressions—decorative, devotional, practical—did not aim at novelty but at continuity, layering the landscapes of their old countries over new soil.

Among Norwegian settlers in places like Decorah, Stoughton, and Westby, rosemaling—the stylized, swirling floral painting applied to trunks, clocks, and walls—took firm root. Originally a Baroque-influenced peasant art from rural Norway, rosemaling in Wisconsin became more idiosyncratic. Artists like Per Lysne, who immigrated to Stoughton in the early 20th century, adapted traditional Telemark and Hallingdal styles to American contexts, adding brighter colors, bolder outlines, and vernacular phrases. Lysne’s painted breadboxes and trunks became cultural icons in the 1930s, helping to codify a “Norwegian-American” aesthetic that still thrives in regional festivals and decorative arts programs.

Polish immigrants, particularly those clustered in Milwaukee’s South Side and Portage County, brought with them wycinanki—the intricate cut-paper art used for window decorations, seasonal festivals, and religious holidays. These fragile works, often symmetrical and brightly colored, depict animals, flowers, and biblical scenes. In Wisconsin, they sometimes took on hybrid forms, combining traditional Polish motifs with Midwestern imagery: chickens and cows nestled among tulips and hearts, or barns standing in for thatched Polish cottages.

The German influence—strongest in Milwaukee, Sheboygan, and rural central counties—entered more through script and structure. Fraktur, a folk art blending calligraphy, illuminated lettering, and symbolic motifs, was originally used for documenting births, baptisms, and marriages. In Wisconsin, it adorned family Bibles, community ledgers, and school awards, preserving both language and lineage. The tension between gothic precision and exuberant imagery—eagles, angels, vines—made fraktur a uniquely introspective form of public art.

These traditions were more than decorative. They were forms of place-making and cultural survival, applied to furniture, walls, prayer books, and textiles—not for audiences or collectors, but for families and neighbors. Their visual languages weren’t merely preserved; they were transformed by the new materials, economies, and climates of the upper Midwest.

Sacred aesthetics: from Lutheran altarpieces to Catholic shrines

Religious art among Wisconsin’s immigrant communities wasn’t restricted to private acts of ornamentation. It also found form in churches—structures that became both spiritual and artistic anchors for new settlements. Unlike the iconoclastic minimalism of early New England Protestants, the Catholic and Lutheran traditions brought to Wisconsin were often lushly visual.

In small rural towns, one finds hand-painted altarpieces in Lutheran churches, many of them constructed by German and Scandinavian woodworkers who doubled as amateur painters. Their works combined biblical storytelling with decorative carving, often framed by floral garlands or gilded columns. The theological simplicity of the Protestant message didn’t exclude visual richness; it translated into accessible grandeur.

Catholic churches, particularly those serving Polish, Italian, and Irish congregations, tended to emphasize the miraculous and the monumental. The Basilica of St. Josaphat in Milwaukee—modeled after St. Peter’s in Rome and constructed by Polish immigrants in the 1890s—contains frescoes, stained glass, and elaborate plasterwork that rival many East Coast cathedrals in ambition. Less monumental but equally telling are the grottoes and roadside shrines scattered through the countryside. These small structures—built of local stone and shells, often housing statues of Mary or Christ—reflect a tactile spirituality, one rooted in touch and terrain.

In some cases, individual artists or visionaries turned devotional work into comprehensive environments. Father Matthias Wernerus’s Holy Ghost Grotto in Dickeyville, completed in the 1920s, is a sprawling, kaleidoscopic cluster of glass, stone, tile, and concrete—part folk art, part catechism, part fever dream. Its chaotic symmetry and dazzling surfaces blur the lines between sacred architecture and outsider installation.

Such works form a parallel canon of Wisconsin art history—one not grounded in formal training or academic aesthetics, but in labor, devotion, and immigrant persistence. They offer an alternate genealogy of artistic intent: not to impress the art world, but to impress the divine.

Handcraft and heritage in rural domestic spaces

Much of the immigrant art in Wisconsin never reached public display. It lived in quilts, embroidery, painted walls, and carved furniture—domestic spaces where cultural transmission happened through touch and repetition. Women were the principal custodians of this visual memory. Their patterns were not only aesthetic but mnemonic: stars for navigation, flowers for regions left behind, birds for children lost in infancy. Quilting circles and sewing bees were not just social events—they were aesthetic workshops and community archives.

In farmhouses across the state, painted furniture from the 19th century survives as a silent witness to this heritage. Cabinets daubed with tulips and vines, rocking chairs inscribed with biblical verses, and chests lined with handwoven linens reflect a mode of visual culture that valued intricacy and modesty in equal measure. Decoration was not a luxury; it was a form of respect—for the object, for the ancestors, for the continuity of home.

These aesthetics were rarely recorded in newspapers or museum catalogues. Yet they formed the substratum of Wisconsin’s regional style—a sensibility marked by bright color, symbolic density, and a deep regard for materials. They also foreshadowed the state’s later embrace of folk and outsider art, creating a continuum rather than a rupture.

Three resonant examples of this domestic visual tradition include:

- A Czech-American painted cradle from Kewaunee County, passed down through five generations, each layer of paint preserving a different era’s palette.

- A Lithuanian embroidered altar cloth from a rural church near Marathon, its geometric patterns echoing Baltic pagan symbols woven into Christian use.

- A set of Swedish Dala horses carved and painted by a father and daughter in Rock County, their evolving style tracking the family’s gradual linguistic shift from Swedish to English.

These works were not made for exhibition, but for transmission. They were meant to be used, touched, and lived with—art as inheritance, not artifact.

The folk traditions brought by Wisconsin’s immigrants did not fade with assimilation; they morphed. They fed into later waves of regional art, craft revivalism, and even aspects of contemporary design. Their echo lingers in painted mailboxes, roadside murals, and community festivals—not relics, but continuing expressions of what it means to make something beautiful, and to belong.

Frontier Portraits and Prairie Studios: 19th-Century Settler Art

Traveling painters and the myth of wilderness

The visual identity of 19th-century Wisconsin was shaped not just by what was seen, but by who did the seeing. As the frontier was charted, claimed, and settled, artists arrived with easels and oils in tow—some commissioned, others itinerant. Their task was not simply to depict the landscape but to interpret it, to render an unfamiliar world legible to an eastern or European imagination. In doing so, they helped manufacture the aesthetic of the American frontier—an imagined space of promise, purity, and manifest order.

Many of these early painters were self-taught or had minimal formal training. They moved from town to town, painting portraits of local notables, recording new buildings, or commemorating land purchases. In places like Prairie du Chien and Green Bay—early centers of trade and military presence—these artists documented a liminal phase: settlements emerging from wilderness, log cabins giving way to clapboard houses, Indigenous presence still visible but increasingly marginalized.

One such artist was Samuel Marsden Brookes, who opened a studio in Milwaukee in 1854. Though best known later for his still lifes, his early work included portraits of fur traders, lumber magnates, and political figures—a visual who’s-who of early Wisconsin society. His calm, symmetrical compositions projected dignity and order onto lives built from volatility.

But even more crucial were the anonymous or semi-anonymous artists who left behind likenesses of farmers, merchants, and children. These portraits, often painted on commission and displayed prominently in parlors or dining rooms, were as much aspirational as documentary. They depicted not just the sitter’s features but their social hopes: a lace collar, a book, a plump-cheeked child holding a flower—these were symbols of rootedness in a land still in flux.

These works were rarely innovative in style. They borrowed heavily from academic conventions and print culture. But they served a deeper function: they stabilized identity in a place where everything else was provisional. In that sense, portraiture on the Wisconsin frontier was a form of cultural infrastructure.

John Mix Stanley and Native subjects through white eyes

While frontier settlers commissioned portraits to assert their presence, another genre—more ideologically charged—emerged alongside it: the romanticized depiction of Native Americans. Artists like John Mix Stanley, who traveled through Wisconsin in the 1840s, painted scenes of Ho-Chunk and Ojibwe life with a blend of curiosity, admiration, and colonial inevitability.

Stanley’s works, many of which were destroyed in the 1865 Smithsonian fire but survive in reproductions and sketches, presented Indigenous figures as both noble and doomed. In Indian Village on the Frontier, for example, he shows a group of Ojibwe figures resting at the edge of a clearing, their canoes pulled ashore, while settlers build cabins in the background. The message is not subtle: one world fading, another rising.

Such paintings were popular in eastern cities, where they fed the appetite for both anthropological novelty and imperial reassurance. Stanley’s skill lay in composition and detail—he paid attention to clothing, gesture, posture—but the larger narrative was always one of vanishing. These works offered the viewer a sense of witnessing the “last moments” of a people, even as those same people were actively resisting removal and negotiating new terms of cultural survival.

Wisconsin’s role as both a home and a crossroads for many Indigenous nations made it a frequent subject of such imagery. Painters, illustrators, and later photographers came to record “types”: the Ho-Chunk mother, the Menominee elder, the Ojibwe warrior. These images circulated widely in newspapers and lithographs, shaping national perceptions even as they erased individual lives.

Three images typical of this genre include:

- A lithograph of “Chippewa Camp” published in Harper’s Weekly in 1856, showing teepees nestled in pine forest, with a lone hunter silhouetted against the setting sun.

- A watercolor by Paul Kane of a Ho-Chunk leader near Portage, rendered with careful detail but stiffly posed, more ethnographic than intimate.

- A sketch by Increase A. Lapham of an Ojibwe burial scaffold, annotated with archaeological notes, part image, part appropriation.

These works reflect not only the bias of their creators but also the hunger of their audience: for closure, for spectacle, for a visual narrative that aligned with the ideology of westward expansion. In this way, the frontier portrait and the “Indian type” image performed parallel functions—they turned instability into iconography.

Art as documentation in an age of expansion

By the latter half of the 19th century, the settler gaze turned increasingly toward landscape and architecture. The railroad, the telegraph, and the rise of local newspapers created a new demand for pictorial representation: towns wanted to see themselves. In this period, panoramic maps, bird’s-eye views, and illustrated gazetteers flourished. Artists like Henry Wellge and Augustus Koch specialized in lithographic town views, often compiled from direct observation and embellished with idealized civic architecture, parks, and smokestacks.

These panoramas, which hung in post offices and council chambers across the state, were less about topographical accuracy than about boosterism. A village of 800 people might appear as a bustling metropolis of the future. Churches were placed prominently, main streets were widened, and even modest homes were rendered with precision. The effect was both promotional and psychological—a way for residents to imagine themselves as participants in progress.

Alongside this visual civic pride, more pragmatic forms of documentation emerged. Survey sketches, engineering diagrams, and land plat maps often contained decorative flourishes: flourishes that revealed an underlying aesthetic ambition. In a land being partitioned into sections and lots, the act of drawing itself became a quiet form of aestheticization.

Photography, too, began to change the visual vocabulary of the frontier. Studio portraits by local photographers in towns like La Crosse, Fond du Lac, and Wausau show a growing refinement in composition and style. Cabinet cards and tintypes captured not just individuals but families, interiors, and even barns—placing personal identity within a spatial and agricultural frame.

What emerges from this period is not a singular “Wisconsin style,” but a pattern of artistic labor embedded in civic and domestic life. The painter, the surveyor, the photographer, and the printer all worked in overlapping visual systems, shaping how Wisconsinites saw themselves and their surroundings.

By the century’s end, the territory that had once been a wilderness in the settler imagination was now gridded, populated, and pictured. Art had helped make it so—not through abstraction or experiment, but through repetition, assertion, and display. In the next generation, a different ambition would arise: not to document the frontier, but to define modernity.

Making Milwaukee Modern: The Rise of Institutional Patronage

Alexander Mitchell and the cultural ambitions of an industrial city

In the decades after the Civil War, Milwaukee was no longer just a collection of breweries, tanneries, and docks on Lake Michigan—it was becoming a city with aesthetic aspirations. As industry brought wealth and immigrant labor transformed neighborhoods into bustling ethnic enclaves, a new question emerged: what role could art play in a place built on production rather than tradition?

For Alexander Mitchell, a Scottish-born financier and railroad magnate, the answer was clear: art could civilize, dignify, and legitimize a city’s social order. Mitchell began collecting European paintings in the 1870s, acquiring works by Corot, Bouguereau, and Rosa Bonheur. His Milwaukee mansion became a private gallery, its salons arranged to impress visitors with the cultivated taste of an industrial baron. The collection served multiple purposes—it was both personal indulgence and civic message. Milwaukee, it suggested, could claim a place among the cultured cities of the Atlantic world.

Mitchell’s collecting was not unique, but his influence was unusually catalytic. Upon his death in 1887, portions of his collection became foundational to what would become the Milwaukee Art Museum. His legacy helped shape a local culture of arts patronage defined by a blend of European aspiration and Midwestern pragmatism. Unlike Gilded Age collectors in New York or Boston, Milwaukee’s elite did not view art as a marker of inherited nobility. They saw it as a way to balance power with polish.

This ethos extended beyond painting. It animated the formation of music societies, library boards, and architecture commissions. Art was woven into the civic infrastructure—not flamboyantly, but deliberately. Even as smokestacks blackened the skyline, the city’s leaders were dreaming in oil and marble.

The Milwaukee Art Society and its Gilded Age collectors

Founded in 1888, the Milwaukee Art Society was a modest organization with an ambitious mission: to bring the fine arts to a working-class city. Its early exhibitions, held in borrowed spaces and adorned with borrowed paintings, mixed old masters with contemporary American works. The curators weren’t art historians—they were businessmen, lawyers, and teachers who believed that access to art could elevate public taste and strengthen civic identity.

One of the Society’s most persistent champions was Frederick Layton, a meat-packing magnate whose Layton Art Gallery, opened in 1888, was one of the first purpose-built art museums west of the Alleghenies. Designed by Edward Townsend Mix in a restrained neoclassical style, the gallery was free to the public and curated according to a simple principle: exposure to beauty would produce moral and social refinement.

Layton’s acquisitions focused on British and continental artists—Landseer, Alma-Tadema, Jules Breton—alongside emerging American painters like George Inness and Winslow Homer. The gallery avoided avant-garde trends in favor of narrative clarity and technical polish. But its deeper function was pedagogical: it trained the eye, shaped values, and created a cultural backdrop for a rapidly diversifying population.

These efforts bore fruit. By 1910, Milwaukee had developed an active arts ecosystem: amateur art clubs, painting schools, and salon exhibitions were flourishing. Women played a crucial role in this civic aesthetic movement. Organizations like the Woman’s Club of Wisconsin sponsored exhibitions, published art criticism, and pushed for public art installations. Their influence ensured that Milwaukee’s artistic culture was not merely decorative but discursive—a space for argument, education, and visibility.

Three objects that reflect the ambitions of this era:

- A William-Adolphe Bouguereau painting from Mitchell’s collection, depicting classical figures with sensual realism, brought to a city where many labored in factories.

- A Layton Gallery exhibition catalogue from 1895, carefully typeset and annotated, revealing the Society’s commitment to connoisseurship over spectacle.

- A newspaper cartoon mocking the pretensions of the city’s new art patrons, suggesting that even then, Milwaukee’s cultural ambitions sparked public ambivalence.

This tension—between genuine aspiration and performative refinement—would continue to define the city’s artistic institutions well into the 20th century.

From beer barons to benefactors: civic pride through art

If industry built Milwaukee, art helped make it admirable. The men who brewed its beer, forged its engines, and packed its meat increasingly turned to art philanthropy in the early 20th century as a means of civic redemption. Some gave quietly. Others, like the Pabsts and the Schlitzes, gave visibly.

The Pabst Theater, completed in 1895, was not just a performance venue; it was an aesthetic argument. With its Baroque interior, gold-leaf moldings, and Viennese chandeliers, it signaled that Milwaukee could rival the cultural sophistication of Vienna or Berlin. Captain Frederick Pabst understood that beauty was good business. His theater helped attract immigrants with cultural capital—German musicians, Polish dramatists, Czech singers—while projecting an image of Milwaukee as a cosmopolitan city.

Art was also used to organize space and memory. Public statues of Civil War heroes, poets, and civic leaders began to appear in the city’s parks. Designed by both local and European sculptors, these monuments functioned as civic pedagogy, reminding residents—many of whom were recent arrivals—of the values they were expected to share: patriotism, industry, piety.

But the city’s artistic ambitions weren’t merely elite. The Wisconsin Painters and Sculptors organization, founded in 1900, sought to elevate the work of local artists, often trained at the Milwaukee Normal School or in Chicago. These artists painted scenes of Lake Michigan, urban labor, and winter landscapes—not for wealthy patrons, but for middle-class collectors, libraries, and schools.

One telling example: the rise of art education in public schools. Drawing was taught not as a leisure activity but as a practical skill, useful in industry and architecture. Yet the line between utility and expression remained porous. A 1908 school exhibition featured works by children that imitated the styles of contemporary American painters—revealing how deeply the city’s aesthetic values had penetrated everyday life.

Milwaukee’s art institutions didn’t merely house art; they trained audiences, validated identity, and modeled behavior. In a city defined by labor, immigration, and ambition, art was not a luxury. It was a framework for becoming modern.

Water, Brick, and Wood: Architectural Aesthetics of a Shifting Region

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School revolution

For much of the 19th century, Wisconsin’s architecture followed a pragmatic formula: wood-frame farmhouses, brick storefronts, gabled churches. Beauty, where it emerged, was a byproduct of function. But in the early 20th century, an architect born in Richland Center would transform not only the look of buildings in Wisconsin, but the very idea of how they should sit in the world.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School vision was not simply a style—it was a philosophy of integration. Trained in Chicago and nurtured by Unitarian ideals and transcendental thought, Wright imagined homes that grew out of the landscape, not upon it. His early designs—most famously the Winslow House in Illinois and the Dana-Thomas House in Springfield—eventually culminated in a series of seminal Wisconsin works that grounded his architectural revolution in native soil.

Taliesin, his personal estate in Spring Green, is both a built environment and an aesthetic manifesto. Originally constructed in 1911, rebuilt after arson in 1914, and reimagined multiple times until Wright’s death in 1959, Taliesin is less a structure than a landscape in dialogue. Perched on a hill among low-slung valleys, it employs local limestone, cantilevered terraces, and horizontal planes to echo the driftless region’s geological character. Interior walls seem to flow outward, windows wrap around corners, and light is allowed to filter rather than glare—an architecture of mood, not monument.

What made Wright’s Wisconsin work so potent was its refusal of European mimicry. At a time when Milwaukee barons were still importing neoclassical columns and French chandeliers, Wright built homes with low eaves, native materials, and Japanese-inspired minimalism. His vision became synonymous with the American Midwest—not a place of provinciality, but of architectural innovation.

Three significant Wright structures in Wisconsin that embody this vision:

- The Johnson Wax Headquarters (1936–39) in Racine, whose lily-pad columns and curved glass tubing redefined the corporate workspace.

- The Unitarian Meeting House (1947–51) in Madison, which treats sacred space as community gathering rather than hierarchy.

- Wingspread (1938), the home of H.F. Johnson Jr., where a central hearth replaces the traditional façade and the ceiling rises like a tent to honor both family and sky.

Wright’s influence would radiate outward—through students, imitators, and critics—but it remained most deeply rooted in the rhythms of Wisconsin’s seasons, woods, and horizons.

Cream City brick and vernacular innovations

While Wright reshaped the high end of residential and institutional design, Wisconsin’s towns and cities evolved in parallel, often guided more by material than ideology. The most distinctive of these materials was Cream City brick—pale yellow and made from the clay of Milwaukee’s Menomonee River Valley. Used extensively between the 1850s and 1890s, it became an aesthetic identifier: to this day, a Cream City façade means Wisconsin.

Cream City brick weathers from butter-yellow to soft beige, often with streaks of orange or rose depending on the kiln conditions. Its popularity arose from practical concerns—it was cheap, local, and relatively fire-resistant—but it soon acquired a symbolic dimension. Factories, schools, breweries, and even mansions wore this subtle palette, marking a departure from the red-brick industrialism of the East Coast or the granite monumentality of Chicago.

Milwaukee’s architecture in this period reflected both ambition and adaptation. German immigrant architects, such as Henry C. Koch and Alfred Clas, combined Gothic, Romanesque, and Queen Anne elements into a regional eclecticism. The Milwaukee City Hall (1895), with its soaring Flemish-style tower and open arcade, exemplifies this fusion. It is grand, certainly, but not imperial. The ornament is intricate but not indulgent. This was a civic architecture that tried to impress without intimidating.

Outside the city, the architectural vernacular turned to function. Barns with Gothic arches or gambrel roofs dotted the countryside, while farmhouses often followed the I-house pattern: two rooms wide, one room deep, with a central hall. The beauty was in proportion and pragmatism. Materials—white pine, local stone, handmade shingles—carried visual codes of durability and frugality.

Some surprising vernacular innovations from this period include:

- The round barns of Vernon County, inspired by Shaker models but adapted for hilly terrain and dairy efficiency.

- Norwegian log houses in the Driftless region, built with dovetail joints and steep gables to shed snow and anchor memory.

- Lannon stone structures in Waukesha County, using glacial dolomite in rough-cut, light-gray blocks to create textured civic buildings.

These were not designed as aesthetic objects, but they have become such through the layered patina of use, weather, and regional identity.

Churches, barns, and the silhouette of labor

To drive across rural Wisconsin is to move through a landscape of silhouettes: white church steeples rising over cornfields, red barns pressed against gray sky, grain elevators marking the economic pulse of a town. Architecture here is less about façade and more about form. It carves space out of utility and transforms it into visual memory.

Church architecture, especially, reveals the evolving identities of immigrant communities. Polish Catholics in Pulaski built onion-domed sanctuaries recalling Kraków; Swedish Lutherans in Rockford opted for modest spires and simple stained glass. Inside, hand-carved altars and painted ceilings reflected the folk traditions of their congregants—art applied not as luxury, but as prayer.

Barns, too, carried aesthetic dimensions beyond their function. Painted quilts on their sides, family crests above their doors, and geometric patterns of timber framing rendered them unexpectedly beautiful. As the 20th century advanced, silos rose beside them like sentinels, introducing vertical drama to a horizontal world.

This silhouette aesthetic—low buildings punctuated by singular towers—has become a defining image of Wisconsin. It shapes everything from tourism brochures to modern landscape photography. And it persists because it is honest: it reflects work, seasonality, and persistence.

In the postwar years, architectural modernism would begin to flatten these distinctions, introducing steel, glass, and boxy neutrality. But even today, the ghost of the vernacular endures. You can see it in reclaimed barns turned into restaurants, in new homes that mimic gabled roofs and wraparound porches, and in public buildings that borrow Cream City hues for their brickwork.

Wisconsin’s architectural history is not linear. It’s layered—like the land beneath it, shaped by ice, wood, fire, and weather. From the visionary asymmetry of Wright to the humble symmetry of the round barn, the state’s buildings tell a story of how people adapted form to place—and place to memory.

Between Grain Silos and Avant-Garde: Wisconsin Artists in the Early 20th Century

Carl von Marr and the Munich connection

At the turn of the 20th century, Wisconsin artists were simultaneously looking outward—to Europe’s ateliers—and inward, to the evolving landscapes and identities of their home state. Nowhere was this tension more evident than in the work of Carl von Marr, Milwaukee-born and Munich-trained, who became a kind of transatlantic bridge between the old world and the new.

Born in 1858 to German-American parents, Marr studied at the Royal Academy in Munich and became one of the few Americans to earn significant recognition in the European academic art world. His magnum opus, The Flagellants (1889), is a sprawling, emotionally intense history painting depicting a 14th-century religious procession during the Black Death. The painting’s dramatic chiaroscuro and monumental scale placed Marr squarely in the lineage of Delacroix and Gérôme, earning him medals in Berlin and Paris.

But Marr’s connection to Wisconsin remained firm. He returned regularly to Milwaukee, exhibited at the Layton Art Gallery, and eventually took on a civic role, helping to shape local art education and collection practices. His example—of an artist who could succeed abroad while maintaining Midwestern ties—inspired a generation of painters and sculptors who saw no contradiction between regional roots and cosmopolitan aspiration.

Marr’s success abroad underscored Milwaukee’s early 20th-century efforts to present itself as a cultural equal to cities like Boston and Chicago. But it also highlighted the paradox Wisconsin artists faced: recognition often required departure. To become “serious,” one often had to leave.

Still, Marr was not a transplant but a loop—proof that cultural currents flowed both ways. His presence helped convince local patrons and students that art in Wisconsin could be both worldly and situated.

Edward Steichen and photographic modernism

If Carl von Marr represented the persistence of academic painting, Edward Steichen embodied the pivot toward photographic modernism. Born in Luxembourg in 1879 and raised in Hancock and later Milwaukee, Steichen would become one of the 20th century’s most influential image-makers—painter, photographer, curator, and editor—whose work helped define the boundaries of what photography could be.

Steichen began as a pictorialist, manipulating photographs with soft focus and painterly effects to lend them emotional gravitas. His early photographs of Wisconsin forests and Lake Michigan beaches are suffused with atmospheric melancholy, their compositions echoing the tonal subtlety of Whistler or Turner. These works didn’t document so much as translate landscape into mood.

But Steichen’s career would evolve rapidly. After co-founding Camera Work with Alfred Stieglitz and exhibiting in the landmark 1905 “291” gallery shows in New York, Steichen turned toward commercial and fashion photography. He brought formal innovation to portraits and magazine work—transforming celebrity into iconography.

Even as he shot for Vogue and Vanity Fair, Steichen never entirely severed his Wisconsin roots. His early exposure to nature and solitude—along the state’s lakefronts and prairies—left a persistent trace in his compositions. Later in life, his role as curator of The Family of Man exhibition at MoMA (1955) reflected a kind of Midwestern humanism: earnest, panoramic, universalist.

In Steichen, Wisconsin produced an artist who was both global and grounded. He redefined photography, but he carried the sensibility of the state’s open horizons and intimate naturalism into every frame.

Milwaukee’s WPA murals and regionalist allegory

During the Great Depression, Wisconsin—like much of the nation—turned to art as a form of public reassurance and ideological clarity. The Federal Art Project (FAP), under the larger umbrella of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), funded murals, sculptures, and community art initiatives across the state. These works were not avant-garde experiments; they were visual declarations of stability, labor, and shared identity.

In Milwaukee and Madison, post offices and courthouses became canvases for regionalist painters who celebrated agriculture, industry, and cooperation. Artists like Santos Zingale and Robert von Neumann created murals depicting dairy farmers, machinists, and factory interiors—images that simultaneously dignified labor and distilled myth.

Zingale’s 1940 mural in the Milwaukee County Courthouse, Wisconsin Agriculture and Industry, is typical of the form: figures arranged in muscular harmony, each task elevated to near-heroic status. There is no chaos, no critique. The Depression-era mural was an art of reassurance—pictorial order against economic disorder.

Yet these murals weren’t simply propaganda. They contained layers of ambiguity. In Von Neumann’s Shipbuilders (1937), painted in the Manitowoc Post Office, the figures strain under weight, their bodies tense, the sky dark. Even as the mural affirms labor, it also dramatizes its toll.

The WPA era also helped democratize access to art. Community art centers in Kenosha, Racine, and Superior offered free classes, exhibitions, and lectures. These weren’t merely educational—they were aspirational. They treated every citizen as a potential participant in the state’s cultural life.

Three emblematic outcomes of the WPA moment in Wisconsin:

- The series of rural-themed murals in the Mount Horeb Public Library, painted by Jean Crawford Adams, that mixed folktale and social realism.

- A set of woodcut prints by Milwaukee artist Gerrit Sinclair, depicting urban street life in stylized, stark forms.

- The Madison Art Center’s 1939 exhibition “Wisconsin in Art,” which gathered paintings from across the state in an early effort to define a cohesive regional style.

Together, these efforts produced a visual language of pride and perseverance. They suggested that Wisconsin’s landscapes—its silos, taverns, assembly lines, and grain elevators—were not merely utilitarian but worthy of artistic vision.

In the early 20th century, Wisconsin’s artists moved between silos and salons, town halls and ateliers. Their work reflects not a coherent style but a shared ambition: to render visible the dignity of place, whether that meant picturing wheat fields or photographing Greta Garbo. Between Marr’s Munich canvases, Steichen’s photographic experiments, and the WPA’s populist murals, Wisconsin art in this period formed a triangulation—between past and future, tradition and experiment, the local and the global.

The Rural Surreal: Magic, Mystery, and Midwest Memory

The art of Mary Nohl and the outsider imagination

There is a house on the shore of Lake Michigan in Fox Point, Wisconsin, surrounded by concrete sculptures: giant fish with puckered mouths, squat figures with almond eyes, columns topped with spiral glyphs. Known locally as the “Witch’s House,” this was the lifelong home and studio of Mary Nohl—a formally trained artist whose work resists every category imposed by the art world. Her life, and her yard, remain one of the most confounding and iconic sites of Midwest visual invention.

Born in 1914 to a wealthy Milwaukee family, Nohl studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, trained in commercial design, and returned home to live a largely reclusive life creating an environment saturated with symbols. Her art was neither hobby nor career; it was compulsion, devotion, and philosophy. She turned her house into a total artwork—filling it with handmade furniture, stained glass, drawings, and cement sculptures constructed from beach flotsam and industrial leftovers.

Nohl’s figures—often humanoid, sometimes animal—seem caught between worlds. They echo totemic carvings, surrealist automatism, and cartoon simplicity, but they belong to no lineage. Instead, they speak in a private language. Their repeated motifs—eyes, spirals, open mouths—suggest a cosmology shaped by solitude, shoreline, and a kind of stubborn interior logic.

Though she was not strictly an “outsider” artist (she had formal training), Nohl’s practice shared the core elements of outsider aesthetics:

- A sustained commitment to a singular vision, made without regard for audience or market.

- An integration of life, space, and art into an inseparable ecosystem.

- A sense of magical thinking applied to the most mundane materials.

For years, her neighbors fought to have her sculptures removed, seeing them as eyesores or pagan symbols. After her death in 2001, her home became the subject of legal battles and preservation efforts. The Kohler Foundation stepped in to preserve many of her works, relocating them to the Art Preserve in Sheboygan and ensuring her vision would not be lost to zoning codes or weather.

Mary Nohl’s house stands as a monument to the idea that art need not be explained to be enduring. In its refusal to conform—to aesthetic categories, to gender roles, to marketable scale—it asserts a Midwestern surrealism: quiet, obsessive, intimate, and powerfully strange.

Joseph Pickett, Tom Every, and visionary environments

Wisconsin has produced more than one solitary builder of worlds. Though less known than their urban or coastal counterparts, these visionary artists have created spaces that blur the lines between sculpture, architecture, and hallucination.

Joseph Pickett, born in 1848 in New Hope, was a former carpenter and storekeeper who began painting late in life. His best-known works—Manchester Valley, Coryell’s Ferry—combine memory, fantasy, and local history into panoramic scenes rendered with childlike proportions and odd, recursive detail. His brushwork is naïve, but the vision is sophisticated. The landscape becomes a stage for emotion, not topography. Pickett’s work feels like recollection as architecture: layered, compressed, and slightly unmoored from realism.

More bombastic, and more contemporary, is the work of Tom Every—better known as Dr. Evermor. A former demolition expert from Brooklyn, Wisconsin, Every created the Forevertron, an immense sculptural environment made from salvaged industrial parts. Centered around a 50-foot-tall “Victorian space machine,” the Forevertron includes telescopes, glass orbs, winged creatures, and a steampunk bandstand—all welded into a single sprawling dream structure.

Every’s vision is both whimsical and apocalyptic. He imagined the Forevertron as a device to launch a Victorian gentleman into the heavens—a satire of invention and a tribute to imagination. Constructed from power plant remnants and brewery vats, it reflects the material history of Wisconsin’s industrial decline, reconfigured into a fantasy of flight.

These visionary environments offer a counter-history to academic and institutional art. They reflect:

- A desire to make art inseparable from place.

- A suspicion of art world hierarchies.

- A belief that beauty can be built, not bought.

They also mark Wisconsin as a state particularly rich in this kind of embedded aesthetic labor—art that arises not from instruction but from obsessive reworking of memory and material.

Domestic psychedelia on the edge of the Great Lakes

What unites Nohl, Pickett, Every, and other visionary Wisconsin artists is not a shared aesthetic, but a shared premise: that the world, especially the rural or liminal world, contains hidden energies. These artists didn’t retreat into fantasy to escape their surroundings—they uncovered the fantasy latent within it.

In their hands, barns become altars, scrap metal becomes prophecy, and memories become map-like landscapes. The rural surreal is not a movement but a condition—a way of seeing isolation as fertile, silence as loud, the ordinary as charged.

This strain of visual culture echoes in contemporary Wisconsin artists working in fiber, assemblage, and print. Artists like Terese Agnew, whose quilts incorporate thousands of pieces of recycled fabric to depict labor and environmental history, or Martha Glowacki, whose cabinets of curiosity reimagine natural history through poetic taxonomies, extend this tradition. Their work draws from domestic craft, scientific illustration, and metaphysical speculation.

There is also something psychedelic—not in the hallucinatory or drug-fueled sense, but in the original Greek: “mind manifesting.” These works do not reflect consensus reality. They amplify it, mutate it, charge it with myth.

Three unexpected echoes of this rural surreal in modern Wisconsin:

- A hay bale sculpture competition in rural Dane County, where farmers build dragons, Elvis heads, and alien spacecraft out of straw.

- A Sheboygan yard filled with whirligigs made from fans, clocks, and doll parts—kinetic prayers to entropy.

- An artist residency in Mineral Point that produces hand-bound books containing invented alphabets and imaginary natural histories.

These may not hang in white-cube galleries or command six-figure auction prices, but they represent a deeper continuity. They affirm that Wisconsin’s visual imagination thrives not just in museums, but in sheds, gardens, basements, and dreams.

The rural surreal is not nostalgia. It is resistance to flattening—to the rationalization of place, the monetization of memory, the reduction of magic to utility. It persists because the land demands it. Because the lake whispers. Because the cornfields bend in wind patterns no one can quite explain.

Cold Light, Thick Woods, Open Water: Wisconsin’s Environmental Aesthetics

Artists and the northern sublime: forests, lakes, and seasonal violence

The landscape of Wisconsin exerts a kind of gravitational pressure on its art. Here, the environment is not backdrop but antagonist, muse, and collaborator. The north woods, the ice-crusted lakes, the endless cornfields under hardening skies—these are not passive subjects. They shape the rhythm and texture of visual language in the state. Artists here do not simply depict nature. They contend with it.

The notion of the sublime, often invoked in the context of Romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich or the Hudson River School, finds a grittier, less triumphant expression in Wisconsin. The state’s version of the sublime is more intimate and less heroic—closer to endurance than awe. Snow drifts are not metaphors; they are barricades. The forest is not allegorical; it is simply dense, indifferent, and always there.

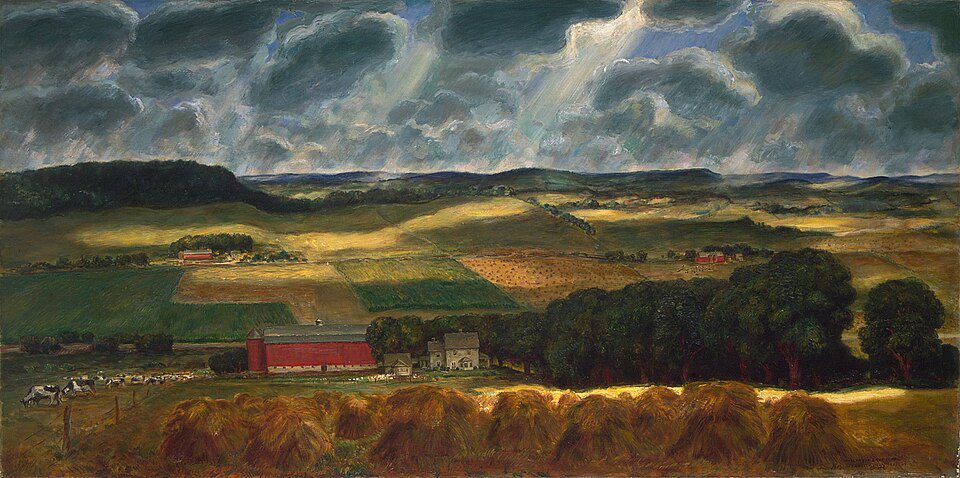

Painters such as John Steuart Curry—though more often associated with Kansas—spent formative years working in the Driftless region, where the land dips and folds with glacial irregularity. His work, with its storm-churned skies and muscular figures, captures not just the look but the psychological weather of Wisconsin.

Others, like Wisconsin-born landscape painter Frank Enders (1860–1921), carried European academic techniques into local forests and marshes, creating brooding, dusky scenes of the Wisconsin River valley. In his work, one finds a compositional tension between pastoral calm and vegetal chaos. Trees do not simply frame the scene; they press inward.

This environmental pressure is not limited to canvas. It shapes how photographers, sculptors, and fiber artists use material and space. Light behaves differently in Wisconsin. It arrives at oblique angles, refracted by ice or dense foliage, yielding a palette that is paler, colder, and more granular than in more temperate zones. The changing of the seasons is not just visual but structural. It dictates medium, duration, and risk.

Three recurring elements in the Wisconsin environmental aesthetic:

- Snow as surface and subject—at once obliterating detail and creating new visual grammars of contrast.

- Trees as both linear framework and psychological motif—obstructing, protecting, hiding.

- Water as mirror, threat, and passage—particularly in the vast inland lakes that can seem as isolating as oceans.

The result is an art that rarely idealizes nature, but frequently engages it with something close to reverence—tinged with anxiety, respect, and sometimes dread.

Ecology and expression in land art, plein air, and conservation painting

Beyond landscape depiction, Wisconsin artists have long used the environment not only as subject but as medium. Land art, outdoor installation, and plein air traditions here draw on a cultural intimacy with natural rhythms—one sharpened by both ecological precarity and practical knowledge of terrain.

One clear strand of this ecological art-making is the plein air tradition that flourished in Door County and along the Mississippi bluffs. Artists like Gerhard Miller (1903–1968) created vibrant yet formally controlled outdoor scenes that balanced regional specificity with universal themes of light, labor, and transience. These painters did not treat the land as virgin or unmarked, but as familiar and worked—fields harvested, barns slumping, trees pruned.

At the more conceptual end, land-based artists in the late 20th century began to treat ecology not as aesthetic backdrop but as ethical prompt. Roy Staab, based in Milwaukee, constructs ephemeral sculptures out of reeds, saplings, and ice—floating mandalas that vanish with the weather. His work resists permanence. It aligns with the cycles of water, decay, and rebirth that define much of the state’s climate.

There is also a quieter but persistent thread of conservation-oriented painting—often dismissed as sentimental or decorative, but in fact deeply engaged with environmental observation. Artists like Owen Gromme (1896–1991), sometimes called “the Dean of American Wildlife Artists,” rendered birds, wetlands, and woodlands with technical precision and ecological empathy. His work bridges art and advocacy, reinforcing the cultural importance of the state’s biodiversity.

These ecological approaches resist both abstraction and spectacle. They are embedded in place, scaled to its rhythms, and often fleeting. In their best forms, they offer not escapism but entanglement.

Weather as medium: snow, light, and the texture of rural time

No single element shapes the Wisconsin aesthetic more decisively than weather. More than a backdrop, it is an active constraint and a formal principle. Snow, in particular, acts as both medium and modifier. It levels surfaces, refracts light, and muffles sound. It compresses color into grayscale intervals and forces artists to reimagine contrast, texture, and negative space.

Photographers like Lois Bielefeld and Kevin J. Miyazaki have used snow and rural light not just as subject but as lens—investigating how whiteness, visibility, and spatial clarity affect our understanding of place. In Bielefeld’s portrait series of rural Wisconsin residents, the light is never neutral. It bathes, flattens, isolates, or abstracts, depending on the time of year.

Rural time, too, manifests as visual texture. The cyclical, slow-turning life rhythms of Wisconsin’s farms and forests shape artistic pacing. Projects unfold over seasons, not weeks. The freeze and thaw dictate working windows. Materials must adapt to moisture, wind, and decay. For some artists, this has meant embracing fragility. For others, it means finding durability in the humble—using barnwood, canvas tarps, frost-resistant pigments.

Three contemporary artworks that reveal weather as structuring principle:

- An ice sculpture constructed on Lake Mendota each January, designed to collapse elegantly with the thaw.

- A video installation capturing the change in daylight color temperature in Eau Claire over the course of a year.

- A sculpture made of harvested field corn, designed to be consumed by deer and birds—weather dictating lifespan, audience, and form.

These works participate in a larger, slower form of place-making—one grounded in cycles rather than markets, intimacy rather than abstraction. They remind us that art in Wisconsin is rarely separable from its context. The environment is not a theme. It is a condition of production.

In a state where land is both resource and witness, art functions as a kind of pact. To depict the forest, the lake, the snowfield, is to acknowledge their primacy—and their mystery. To work with them is to recognize that art is not above nature, but always within it.

Academic Aesthetics: UW-Madison and the Postwar Art School Boom

Mauricio Lasansky, Warrington Colescott, and printmaking prestige

After World War II, a quiet revolution unfolded in Wisconsin—not on the gallery walls of Milwaukee, but in the studios and classrooms of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The GI Bill had opened higher education to thousands of veterans, and the state’s flagship university responded by investing heavily in the arts. What emerged was not simply a degree program, but one of the most influential printmaking hubs in the United States.

Mauricio Lasansky, an Argentinian-born printmaker trained in the traditions of Goya and Käthe Kollwitz, arrived in Madison in the early 1940s before eventually founding a legendary program at the University of Iowa. His influence, however, helped spark a wave of technical innovation and seriousness that shaped Madison’s own art department. Building on Lasansky’s legacy, Warrington Colescott—a Wisconsin-born artist with a sharp satirical eye and deep command of etching—brought international attention to the university’s printmaking scene in the 1960s and ’70s.

Colescott’s prints are absurd, brilliant, and densely layered. In series like History of Printmaking or The German Wars, he skewered historical hubris and institutional hypocrisy with comic verve. Unlike the solemn political prints of earlier generations, Colescott’s work teemed with grotesque caricatures and surreal juxtapositions—Rembrandt hovering over nuclear blasts, Goya shaking hands with Dürer, soldiers cavorting in absurdist battlefields. The technical mastery was unassailable; the tone, utterly irreverent.

This synthesis—virtuosity and subversion—became a hallmark of the Madison printmaking tradition. Students learned etching, lithography, woodcut, and screen printing not just as techniques but as narrative languages. The program emphasized both craftsmanship and risk, producing generations of artists who saw print not as reproduction, but as expression.

Three distinct features defined this academic printmaking boom:

- A culture of critique rooted in both formal precision and conceptual ambition.

- A willingness to mix high and low sources—art history, cartoons, politics, and myth.

- A deep commitment to teaching, mentorship, and the idea of the artist as thinker.

In time, Madison’s print studios gained national repute—not just as training grounds, but as laboratories of visual argument.

Studio glass, ceramics, and the push beyond painting

The explosion of interest in postwar studio arts was not limited to print. As modernism fractured and the boundaries between craft and fine art dissolved, Wisconsin emerged as a critical site in the evolution of studio glass, ceramics, and fiber art—mediums long considered marginal or decorative.

Harvey Littleton, often dubbed the “father of the studio glass movement,” began his glassblowing experiments at the University of Wisconsin in the early 1960s. Until then, glass was largely an industrial or decorative medium, shaped in factories rather than studios. Littleton changed that. He designed equipment and curricula that allowed artists to create glass works independently—ushering in a new era of sculptural glass that emphasized form, color, and spontaneity.

Littleton’s students—among them Dale Chihuly—went on to become internationally known, but the philosophical core remained rooted in Wisconsin: an embrace of material intelligence, discipline, and experimentation. Studio glass was not just sculpture; it was physics, light, and intuition in dialogue.

Parallel to this, the ceramics department at UW–Madison was gaining similar stature. Under the leadership of Don Reitz and others, it became a haven for artists who wanted to bridge the utilitarian and the conceptual. Reitz’s massive, wood-fired vessels—cracked, glazed, almost geological—defied both commercial pottery and minimalist sculpture. They asserted presence, not polish.

This confluence of media—glass, clay, print, textile—allowed Wisconsin artists to bypass the painting-centric hierarchy of the coastal art world. While Abstract Expressionism and Pop dominated galleries in New York, Wisconsin built a quieter, slower movement around touch, heat, resistance, and repetition.

A few emblematic works and projects:

- A hand-blown glass installation by Littleton, comprised of elliptical forms suspended in tense gravity.

- A massive stoneware vessel by Reitz, scarred by flame and marked with his signature thumb-impressions.

- A collaborative artist book combining screen printing, letterpress, and hand binding—produced in the UW libraries as part of their book arts initiative.

These works didn’t demand attention so much as reward attention. They insisted that material intelligence was a form of thinking.

Political posters and counterculture graphics in the 1960s and ’70s

By the late 1960s, the campus at UW–Madison was not just a site of artistic experimentation but a hotbed of political activism. Protests against the Vietnam War, civil rights struggles, and feminist movements turned the university into one of the most volatile and creative environments in the country. Art responded—not with solemn memorials, but with loud, colorful, confrontational imagery.

Student-run print shops churned out posters, zines, and flyers that merged psychedelic design with sharp political critique. The influence of West Coast poster culture was evident—echoes of Victor Moscoso and the Fillmore scene—but Wisconsin’s version had a colder edge. The flatness of winter, the severity of Germanic graphic traditions, and the density of academic argument gave the prints a different weight.

The Mifflin Street Block Party posters, the “Mad Dogs for Peace” campaign, the resistance graphics after the Sterling Hall bombing—all used color and typography as acts of protest. These weren’t simply announcements; they were rhetorical images, meant to agitate and galvanize.

This era also saw the rise of feminist graphic collectives and consciousness-raising visual projects. Silk-screened posters addressing abortion rights, anti-rape campaigns, and workplace discrimination circulated across campus and beyond. Artists like Martha Rosler and Judy Chicago visited or exhibited in Wisconsin, influencing a generation of local practitioners.

Three aesthetic features that defined the counterculture print scene:

- Sharp contrast and limited palettes—often due to the constraints of screen printing and photocopying.

- Bold, condensed typefaces paired with surreal or comic imagery.

- A blend of urgency and playfulness—serious topics rendered with stylistic exuberance.

What tied all these practices together was the belief that art was not just commentary—it was action. In classrooms, print shops, kilns, and demonstrations, art in Madison during this era became a force of cultural construction. It was regional not by subject, but by ethic: skeptical, material, resistant to spectacle, and rooted in process.

By the end of the 1970s, Wisconsin had built an art infrastructure as intellectually ambitious and materially diverse as any in the country. It had forged a scene not based on celebrity, but on craft, collaboration, and continuity. That legacy still reverberates in the studios and collections across the state—not as nostalgia, but as a living structure.

Industrial Ruins and Rustbelt Romanticism: Post-Industrial Art

Urban decay and photography as elegy

As the 20th century waned, Wisconsin’s industrial infrastructure—once the engine of its civic and aesthetic confidence—began to rust. Manufacturing jobs declined, warehouses emptied, and once-bustling districts fell into disrepair. In this vacuum, a new genre of artistic expression emerged, one that treated the remnants of industry not as obstacles but as subjects: the art of ruin.

Photography became the primary medium for this encounter. Urban exploration photography—sometimes labeled “ruin porn,” though often unfairly—flourished in cities like Milwaukee, Racine, and Kenosha. Artists documented crumbling factories, abandoned theaters, derelict breweries, and the fading geometries of rusted rail yards. These images did not simply record decay; they composed it.

Photographers like Kevin J. Miyazaki and J. Shimon & J. Lindemann approached the ruins with a mix of formal rigor and elegiac intimacy. Their works rejected sensationalism, instead capturing subtle evidence of time: a child’s toy beneath a broken window, light filtering through a collapsed roof, graffiti that both defaces and reclaims. The photographs became visual elegies, layering nostalgia, critique, and quiet astonishment.

The appeal of industrial ruin was not only aesthetic. It reflected a deeper cultural reckoning. What happens when a place built on labor loses its labor? What kind of art emerges when function ceases and only form remains?

These artists often worked in series, revisiting the same sites over months or years, creating visual narratives of entropy. Their work invited viewers to slow down, to see beauty not in productivity, but in its collapse.

Three visual strategies common in post-industrial photography:

- Symmetry in disorder—finding balanced compositions in asymmetric spaces.

- Natural light as a metaphor for intrusion or redemption.

- Emphasis on textures—peeling paint, oxidized metal, rotting wood—as a form of visual tactility.

The result was a new kind of Wisconsin landscape art: not fields and lakes, but interiors emptied of commerce, charged with absence.

Artists reclaiming factories, train yards, and warehouses

While photographers documented decay, other artists repurposed it. In the 1990s and early 2000s, empty industrial buildings became studios, galleries, and performance spaces. The very sites of economic abandonment became nodes of aesthetic invention.

The Walker’s Point neighborhood in Milwaukee saw a surge of warehouse conversion, driven by artist cooperatives and alternative spaces. The cavernous interiors allowed for large-scale sculpture, installation, and experimental performance—forms that had been squeezed out of conventional galleries. At venues like the Walker’s Point Center for the Arts and the Borg Ward Collective, artists turned spatial excess into creative opportunity.

In Racine, parts of the decommissioned Horlick Malted Milk factory became temporary canvases for muralists and guerrilla artists. In Madison, the Garver Feed Mill—built in 1906 and dormant for decades—was transformed into a hybrid space for food, art, and community projects. These interventions did not erase industrial memory; they metabolized it.

This adaptive reuse became an aesthetic in its own right: exposed brick, visible ductwork, concrete floors—the remnants of industry not concealed but celebrated. The aesthetic of the industrial past became a mark of authenticity and honesty, even as its economic base remained gone.

Artists working in these spaces often integrated found materials—machine parts, signage, wire, wood—into their work. Sculpture, assemblage, and performance art drew directly from the site’s history. The building was not just a container; it was collaborator.

Three notable examples of site-specific reuse in Wisconsin:

- The transformation of Milwaukee’s former Pabst Brewery into a complex housing a microbrewery, artist studios, and event spaces—with historical signage and industrial remnants left intact.

- The Kohler Arts/Industry program, which places artists inside the Kohler Co. factory to create works using industrial processes, blurring the line between labor and art.

- A performance series staged in a disused grain elevator in Eau Claire, where sound and light installations interacted with the acoustics and verticality of the space.

This turn to industrial sites was not nostalgia. It was a form of reclamation—of space, of narrative, of possibility.

Grit as a visual language in contemporary installations

As the aesthetics of decay became more familiar, some artists began to move beyond documentation and adaptation, forging new work that used post-industrial textures as a language. Grit—both literal and symbolic—emerged as a key motif. It signaled not just hardship but resistance to polish, pretense, and disconnection.

Artists like Santiago Cucullu, based in Milwaukee, blend installation, video, and drawing into immersive environments that reference both urban memory and psychic fragmentation. His works often combine images of industrial landscapes with abstract patterns and soundscapes, creating dissonant spaces of beauty and discomfort. The grit is there—not just in subject, but in sensibility.

Others take a more sculptural approach. Milwaukee artist Niki Johnson works with hair, ceramic, and discarded materials to create politically charged objects that combine delicacy and density. Her Eggs Benedict (2013), a portrait of Pope Benedict XVI made from 17,000 condoms, used both material and message to unsettle.

Contemporary grit is not merely aesthetic. It is epistemological—a way of knowing rooted in mess, weight, history, and persistence. In Wisconsin, where economic transitions have been slow and painful, this approach resonates. It refuses the sleekness of art fairs or tech campuses. It insists on friction.

Three recurring motifs in post-industrial contemporary art:

- The use of industrial color palettes: rust, soot, oil, iron oxide.

- Juxtaposition of hard and soft materials: steel with felt, concrete with wool.

- A focus on memory as residue—traces, stains, echoes.

These works rarely offer closure. They open wounds, archive gestures, and mark time not with clocks but with corrosion. They are not sentimental, but they are tender.

Post-industrial art in Wisconsin is ultimately an act of witnessing. It sees what has been lost—work, dignity, continuity—and chooses not to look away. But it also sees what remains: space, form, material, community. It finds art not in the absence of function, but in the reimagination of it.

Biennials, Collectives, and County Fairs: Contemporary Wisconsin Scenes

From the Kohler Arts/Industry residency to the Art Preserve

At the edge of Sheboygan, where Lake Michigan flattens into industrial calm, a factory and a museum together produce one of the most unusual partnerships in American art. Since 1974, the John Michael Kohler Arts Center’s Arts/Industry residency has embedded artists within the Kohler Co. manufacturing plant, granting them access to the same tools, materials, and technicians that make bathtubs, sinks, and faucets. In doing so, it has transformed an industrial site into a crucible of contemporary sculpture, conceptual design, and material experimentation.

Artists in the program do not merely mimic the factory process. They interrogate it. Ceramics, cast iron, vitreous china—these are the materials of domestic utility, but in the hands of resident artists, they become pliable, strange, metaphorical. A sink becomes a reliquary; a toilet, a sound installation. The residue of labor clings to the work, reactivating the old union between art and industry that shaped Wisconsin in earlier centuries.

This approach culminated in the 2021 opening of the Art Preserve, a satellite campus of the Kohler Arts Center dedicated entirely to the display of artist-built environments. Far from sterile white walls, the Preserve embraces chaos, color, and personal mythology. It houses sprawling works by artists like Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Mary Nohl, and Emery Blagdon—spaces that function not as galleries, but as fragments of a world built by hand and belief.

The Art Preserve does something radical: it treats “outsider” and “visionary” artists not as curiosities, but as central voices in contemporary culture. Their materials—concrete, cardboard, chicken bones—are handled with the same reverence usually reserved for bronze and marble. Their stories are complex, not simplified. Their works are lived-in, not labeled.

Three aspects that make the Kohler model particularly distinct:

- An unbroken continuum between labor and art, industry and creativity.

- A respect for vernacular aesthetics that avoids romanticization.

- A commitment to long-term stewardship rather than trend-based exhibition.

In a national art world increasingly organized around temporary spectacle, Wisconsin has, in this corner, created a model rooted in permanence, locality, and serious care.

DIY galleries, rural collectives, and art in the age of social media

But contemporary art in Wisconsin isn’t confined to institutions. In towns large and small, a dense and shifting network of collectives, DIY spaces, and pop-up exhibitions supports a decentralized, vibrant scene. Artists adapt barns into studios, living rooms into screening rooms, and public parks into sculpture gardens. This isn’t an art world—it’s an archipelago.

The Twin Cities proximity brings gravity to western Wisconsin, while Chicago’s influence pulls on the southern counties. Yet many Wisconsin artists choose to stay put, not in rejection of those centers, but in defiance of their necessity. A painter in Viroqua, a printmaker in Stevens Point, a video artist in Wausau—they share work through Instagram, collaborate via Zoom, and ship zines, prints, and textiles across the country.

The rural setting doesn’t isolate. It focuses. Artists here work with what’s around them—found wood, harvested pigment, repurposed objects—creating pieces that resist both high-concept art theory and overproduced slickness. The result is a tactile, deliberate aesthetic that’s more concerned with craft and clarity than novelty.

Contemporary collectives also blur the line between art, activism, and pedagogy. The Wormfarm Institute in Reedsburg, for example, combines sustainable agriculture, artist residencies, and public programming into a model that values ecology as much as aesthetics. Their annual Fermentation Fest includes hay bale sculpture trails, farm dinners, and performances—connecting visual culture to local food, land use, and rural identity.

Some shared features of these decentralized art ecosystems:

- Collaboration over hierarchy—artists as co-curators, not competitors.

- Interdisciplinary practice—where visual art meets farming, brewing, community organizing.

- Emphasis on context—responding to local history, weather, materials, and social dynamics.

Rather than trying to replicate the art capitals, these artists reshape what “art capital” might mean in a rural state.

Navigating regionalism in a globalized art world

All of this—residencies, collectives, outsider environments—raises a question that’s both perennial and urgent: what does it mean to make regional art in a globalized moment? For Wisconsin, the answer has never been straightforward. Regionalism here is not a style, but a stance—a way of remaining accountable to place without becoming provincial.

Historically, the Midwest has been treated as flyover country, even within the American art world. But that invisibility has allowed for freedom: freedom from the pressures of fashion, from the churn of coastal markets, and from the need to explain. Artists here have often worked under the radar, developing long-term projects that defy exhibition cycles or dealer demands.

Today, that invisibility is more a choice than a condition. Wisconsin artists are increasingly aware of their position—and increasingly willing to wield it. Some engage directly with national discourses on identity, environment, or labor. Others stay hyperlocal, making work that speaks only to a 30-mile radius. Both modes are valid. Both resist easy consumption.

One sees this dual orientation in emerging Wisconsin biennials and art fairs. Events like the Wisconsin Triennial (organized by the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art) gather work from across the state, curating it not by medium or fame but by rigor and coherence. These shows often feature artists who straddle multiple realities: a Black Lives Matter muralist who also runs a tattoo parlor in Green Bay; a fiber artist who dyes wool using native plants and posts botanical research on TikTok.

Three tensions that define the experience of making and showing art in Wisconsin today:

- The push for national relevance vs. the pull of local rootedness.

- The pressure to brand vs. the impulse to withhold.

- The desire for visibility vs. the dignity of self-containment.

Contemporary Wisconsin art does not aspire to become the next Brooklyn or Portland. It doesn’t need to. It already has its own ecology: shaped by snow and heat, freight trains and silos, old mills and new collectives. It is quieter than most scenes—but it listens more deeply.

Museums, Memory, and the Future of Place-Based Art

The evolving role of the Milwaukee Art Museum

At the eastern edge of Milwaukee, where Lake Michigan widens into a luminous expanse, the Milwaukee Art Museum stands like a ship poised for departure. Its Quadracci Pavilion—designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava and completed in 2001—features sweeping steel “wings” that open and close daily, transforming the skyline into a kinetic sculpture. It is the most iconic cultural structure in the state, and it signaled a bold ambition: that a Midwestern city known for beer, manufacturing, and immigrant neighborhoods could also claim architectural and artistic distinction.

Yet beneath that gleaming symbol lies a more complex institutional evolution. The Milwaukee Art Museum, formed through the merger of the Layton Art Gallery and the Milwaukee Art Institute in 1957, has long balanced its commitment to international prestige with its responsibilities to regional identity. Its collections include works by Degas, Kandinsky, and O’Keeffe—but also robust holdings in American decorative arts, Midwestern regionalism, and modernist craft.

Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the museum has tried to navigate the tension between global spectacle and local memory. It has hosted exhibitions on Haitian Vodou, European old masters, and global contemporary trends—but also retrospectives on Wisconsin artists like Warrington Colescott, and thematic shows on Great Lakes ecology, Midwestern labor, and vernacular design.

The Calatrava expansion brought attention but also scrutiny. Critics questioned whether the building’s theatricality overshadowed its contents. But supporters argued that the architecture invited broader engagement—pulling in audiences who might not otherwise have walked into a museum. In either case, the structure raised the stakes: Wisconsin’s flagship museum could no longer claim humility as a shield.

Three ongoing challenges that shape the museum’s evolving role:

- Balancing blockbuster exhibitions with sustained investment in local artists and histories.

- Building a diverse audience across class, race, and geography within a state marked by deep economic disparity.

- Positioning itself within a national museum landscape that increasingly demands both relevance and ethical accountability.