The scent of salt and citrus drifts through the narrow alleys of Bari Vecchia, the city’s old quarter, where smooth, time-worn stones underfoot have been passed over by millennia of pilgrims, traders, and invaders. Long before the city became known for Romanesque basilicas and Baroque altarpieces, it was shaped by a far older and more elemental force: the sea. Bari’s art history cannot be extricated from its geography, perched as it is on the edge of the Adriatic, equidistant from Latin Rome and Greek Byzantium, from Venetian traders and North African winds. Its earliest art, fragmentary and often subsumed within later buildings, reveals a city whose first creative expressions emerged not from a stable civic identity but from flux, passage, and collision.

Maritime wealth and early settlements

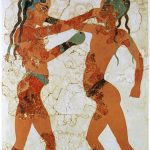

Long before the name “Bari” appeared in Latin documents, the area was occupied by the Peucetians, an ancient Italic people whose burial goods and ceramic forms—found in necropolises around the modern city—reveal a surprisingly rich visual culture. These early settlers, active from the 8th century BC onward, produced painted vases that mixed geometric stylization with figural depictions, suggesting exposure to Greek influence via trade routes. Although little survives in situ, archaeological finds, especially those housed in the Museo Archeologico di Santa Scolastica, show how the Adriatic functioned as a corridor of visual forms.

By the 3rd century BC, the area fell under Roman control. Bari—then Barium—developed as a minor port and municipium, with a modest urban plan and an amphitheater whose remnants are still visible under parts of the modern city. Roman Bari was not an artistic powerhouse, but it was a node in a network, and the sculptural fragments and mosaics uncovered in its vicinity speak of decorative tastes shaped by distant capitals. A floor mosaic now relocated to the Castello Svevo depicts marine creatures in stylized symmetry, suggesting that even here, provincial homes echoed the imperial ideals of beauty and order.

But Bari’s greatest early resource was its location. Not rich in stone quarries or metals, it became valuable for its role in circulation. Wealth passed through, often stopping only long enough to leave a visual trace—a coin, a carved lintel, a tile pattern—before continuing elsewhere.

Byzantine imprint on southern urbanism

By the 6th century AD, the fall of the Western Roman Empire left Bari in shifting hands, but its strategic position brought it into the orbit of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire. For nearly 500 years, Bari existed as a military-administrative outpost of Constantinople. During this time, its artistic vocabulary changed dramatically.

Byzantine Bari was not home to the grand domes and gold mosaics of Ravenna or Constantinople, but its influence was visible in subtler, more hybrid ways. One of the most striking is the use of liturgical space. Churches were often laid out in cross-in-square or three-aisled basilica plans, reflecting a combination of Eastern liturgy and Western forms. Decorative programs favored icons and frescoes—most of which have since disappeared, though traces survive in crypts and chapels across Apulia.

The architecture from this period, while not always visibly “Byzantine” to the modern eye, is characterized by tightly fitted ashlar masonry, horseshoe arches, and distinctive capitals with stylized acanthus leaves. Such features point to workshops circulating between southern Italy and the Aegean. Even more than visual forms, however, it was the administrative use of Bari that shaped its early art history. The city’s role as the seat of the catepanate (the Byzantine governorate of Italy) in the 11th century elevated its stature and spurred building activity, much of which laid the groundwork for later Romanesque flourishes.

Three elements marked this Byzantine legacy in art:

- A preference for sacred figuration over narrative sculpture.

- The persistence of Greek inscriptions in ecclesiastical contexts.

- A liturgical architecture that emphasized mystery, procession, and icons over open, didactic spaces.

These currents, often submerged in later reconstructions, contributed to a cultural layering that would distinguish Bari from other Italian cities in the centuries to come.

The cathedral foundations beneath the sea breeze

It is easy to overlook the Cathedral of San Sabino when the more famous Basilica di San Nicola stands just blocks away, but San Sabino occupies a unique place in the story of early Bari. Built on the ruins of an earlier Byzantine church, itself raised above a Roman-era structure, it encapsulates the city’s sedimentary quality. Excavations beneath the current cathedral reveal pavements and wall traces from at least three distinct phases, each marked by its own artistic language.

The earliest Christian structures in Bari likely followed the pattern of simple house-churches, evolving over time into more formal basilicas. While no complete examples survive, the crypt of San Sabino retains columns and capitals that suggest spolia from late Roman temples—a common practice that infused Christian spaces with the gravitas of antiquity. This reuse was not merely practical; it reflected a continuity of space, an assertion that sacred authority could be transposed from empire to church.

A surprising detail found in the subterranean layers of San Sabino is a fragment of painted plaster showing a stylized peacock—an early Christian symbol of resurrection—executed in a hand that suggests Eastern Mediterranean influence. Though modest in scale, such fragments give insight into a visual world in which sacred art was not monumental but intimate, woven into architectural nooks and devotional corners.

By the end of the 11th century, Bari was poised for transformation. The arrival of Saint Nicholas’ relics in 1087 would catalyze a building boom, setting the stage for an architectural and artistic efflorescence that would merge Norman ambition with local tradition and Byzantine memory. But even as new stones rose skyward, Bari’s deepest artistic roots remained anchored below ground, where columns, pavements, and pigment told the story of a city perpetually shaped by those just passing through.

In Bari, art begins with passage, with the fragments left behind by ships that stayed just long enough to unload their cargoes and leave a piece of their world behind. That spirit of mixture and reuse would come to define the city’s visual culture, even as it reached toward new architectural heights in the centuries that followed.

The Bones of Saint Nicholas: A Turning Point in Art and Identity

The year was 1087. A crew of Barese sailors, emboldened by commercial ambition and religious fervor, sailed across the Adriatic and into the Aegean, landing at the city of Myra—then under Muslim rule. They forced entry into the tomb of Saint Nicholas, removed his relics, and spirited them back to Bari, where they were received not with quiet reverence but with a euphoric procession that transformed the city’s destiny. The bones of Saint Nicholas did more than make Bari a major pilgrimage site—they reoriented its visual culture, altered its architecture, and reshaped its public identity. What began as a daring relic theft became a foundational moment in southern Italian art.

Pilgrimage, prestige, and the construction of a city’s image

In medieval Europe, relics were not just sacred remains—they were currency, insurance policies, political assets. Possessing the bones of a major saint could elevate a provincial town to international prominence. That is precisely what happened in Bari. Saint Nicholas, already venerated across the Eastern Mediterranean, especially by sailors, merchants, and the poor, was an ideal figure for a port city seeking religious stature. His relics, once ensconced in the newly commissioned Basilica di San Nicola, began to attract waves of pilgrims from both Western and Eastern Christendom.

This new status generated a surge of artistic activity. Art was required to celebrate the relics, to manage the crowds, and to materialize the prestige Bari had abruptly acquired. The visual culture that followed combined narrative, monumentality, and spatial drama, all tailored to a devotional experience that was at once intimate and spectacular.

The cult of Saint Nicholas necessitated:

- An architectural stage grand enough for international pilgrims.

- A sculptural program that dramatized the saint’s miracles and virtues.

- Liturgical furnishings that embodied both Latin and Greek traditions.

Bari was no longer a modest Byzantine backwater. It had become, virtually overnight, a city with an international saint—one who would later morph into the folk figure of Santa Claus—and that transformation required new symbols, new spaces, and new stories rendered in stone and paint.

Romanesque architecture meets Greek legend

The architectural response to this seismic change was swift. Construction began almost immediately on the Basilica di San Nicola, a massive Romanesque structure designed to house the relics, host a constant flow of pilgrims, and project a sense of sacred authority. Though the builders remain largely anonymous, stylistic evidence points to Apulian workshops already familiar with Lombard and Norman models, now tasked with inventing something new.

The basilica’s layout is deliberate and processional. A broad nave leads the eye directly to the raised presbytery, beneath which lies the crypt housing the relics. This double-level design accommodates both liturgical needs and devotional traffic. Pilgrims can access the saint’s tomb without disturbing the clergy—a spatial choreography that unites function and reverence.

Visually, the building is defined by its thick stone walls, rounded arches, and sober yet powerful ornamentation. The façade is flanked by blind arcades and features a central rose window added slightly later. While the structure is Romanesque, it is not a copy of northern models; it adapts the idiom to Bari’s own rhythms and materials. Limestone quarried from nearby Murgia gives the exterior its pale, almost luminous quality.

One of the most striking features is the pair of carved lions at the portal—symbols of vigilance and strength. These are not passive decorations; they serve as moral guardians of the space within. Nearby capitals depict both biblical scenes and decorative foliage, suggesting a workshop conversant with multiple traditions: Byzantine, Arab, and Norman. This mingling of styles reflects the city’s hybrid status—not quite Latin, not quite Greek, but something insistently local and new.

The Basilica di San Nicola as spiritual theater

Within the basilica, the most profound visual element is spatial rather than pictorial. The descent into the crypt—dimly lit, low-ceilinged, with a dense colonnade supporting the massive sanctuary above—creates a physical and emotional transition from civic space to sacred intimacy. Pilgrims who had traveled hundreds of miles by land or sea would finally kneel in this crypt, face to face with a marble sarcophagus said to contain the saint’s bones.

Here, art serves as both architecture and atmosphere. Columns, some repurposed from older Roman structures, create a rhythm of repetition and mystery. Frescoes and later icons introduce painted narratives, but the core experience is sculptural and spatial. This was a theater of presence, a choreography of belief. The body of the saint was not on view—it was hidden, inaccessible—but its effects were visible in the way light, stone, and crowd behavior created a sense of contact with the miraculous.

A particularly vivid account survives from a 12th-century Russian pilgrim named Anthony, who described the intense pressure of the crowds, the oil drawn from the relics (believed to have healing properties), and the overpowering emotional response of the faithful. His testimony, preserved in manuscript, suggests that the art of Bari was never merely decorative—it was embedded in ritual, suffused with drama, and enacted through bodies and space.

Midway through the 12th century, a new addition gave visual form to this narrative power: the ciborium, a stone canopy over the altar, supported by slender columns and adorned with sculptural motifs. Though modest in scale, it represented the city’s embrace of architectural symbolism—here, the altar as a new tomb, the columns as apostles, the canopy as the heavens.

This convergence of relic, ritual, and architecture produced something unique in Bari: a sacred art deeply connected to physical space and public identity, but born of an act of piracy. The bones had not been gifted—they had been taken. And yet, their arrival transformed Bari from a peripheral city into a spiritual capital of the Adriatic.

Even today, the Feast of Saint Nicholas each May continues to blend the sacred and the theatrical, with processions, boats, and blessings reenacting the saint’s arrival. Art, in Bari, begins not in a studio or court, but in the streets, the port, and the crypt—carried on shoulders, sung in Greek and Latin, and carved in limestone to outlast the salt winds.

Norman Patrons and the Southern Romanesque

In the wake of Saint Nicholas’ arrival and the construction of his basilica, Bari entered a new era of artistic ambition. The Norman conquest of southern Italy in the 11th century brought not only military control but also a seismic reorientation of the region’s patronage networks. No longer beholden to Byzantine administrators or local bishops alone, Bari’s artists and architects now answered to a newly powerful Latin elite—Norman rulers eager to leave their mark in stone. This shift catalyzed one of the most distinctive regional styles in Italy: the Southern Romanesque, an aesthetic born from conquest but refined in dialogue with older traditions. Bari stood at its epicenter.

A conquest that brought capital and artisans

The Normans, originally Scandinavian settlers in northern France, had by the 11th century transformed themselves into seasoned warriors and savvy political operators. Under Robert Guiscard and his brother Roger, they swept through southern Italy and Sicily, defeating Byzantine forces and carving out a string of territories. Bari, captured in 1071 after a protracted siege, became a key military and administrative outpost in this new Latin kingdom. But the Normans were not cultural iconoclasts. On the contrary, they quickly grasped the prestige and propaganda power of art.

With Norman rule came an influx of resources: land grants, ecclesiastical appointments, and—critically—wealth from trade and taxes. This allowed for a flowering of architectural commissions not only in Bari but across Apulia. The Normans sponsored cathedrals, monasteries, and castles, often building atop or alongside older structures. Their architectural ambitions were not confined to military strongholds; they extended to sacred and civic spaces designed to assert authority through beauty.

The influence of Norman patronage can be seen in:

- The monumentalization of religious buildings with fortified façades.

- The importation of northern masons and sculptors to work alongside local craftsmen.

- A shift from subtle, Byzantine-style embellishment to more assertive decorative programs.

Bari’s transformation under Norman patronage was not an isolated occurrence but part of a broader strategy to Latinize and centralize southern Italy—one building at a time.

Sculptural programs and the carved façade

One of the most visible innovations of this period was the rise of narrative and symbolic sculpture as a dominant visual language. Whereas earlier art in Bari leaned toward flat fresco and mosaic, the 12th century saw a surge in sculptural adornment, particularly on church façades and portals. These were not merely decorative— they functioned as theological texts and political statements in stone.

The Basilica di San Nicola, though initiated before full Norman control, was completed under their influence and remains the best example of this new aesthetic. Its west façade, austere yet monumental, is framed by carved pilasters and a series of blind arcades. Above the main portal, sculpted panels depict saints and beasts—some local, others drawn from bestiaries and Latin iconography. The capitals inside the basilica, particularly those in the nave, offer a compact encyclopedia of biblical narratives, vegetal motifs, and abstract designs.

But it is in the portals of Bari’s other major churches—San Sabino, San Gregorio, and the now partially lost churches of Santa Scolastica—that the full range of Apulian Romanesque sculpture comes into view. These doorways teem with creatures: lions devouring men, centaurs brandishing bows, griffins clutching prey. Many of these images derive from northern traditions but are reimagined here with a local inflection—compressed into narrow spaces, framed by elaborate archivolts, or fused with vegetal scrolls.

A recurring feature is the use of telamons—figures carved as if they are physically bearing the weight of the structure. These appear not just as architectural supports but as moral emblems: sinners, fools, or pagans struggling under the burden of divine law. Such images suggest a didactic function for architecture, turning the very act of entering a church into a moral allegory.

Three features distinguished Apulian Romanesque sculpture from its northern counterparts:

- A fondness for grotesque, often humorous hybrid beasts.

- The compression of narrative scenes into narrow vertical registers.

- The integration of text—both Latin and Greek—into the visual field.

This last feature is especially striking. Several church portals in Bari include carved inscriptions in Greek, a reminder that, even under Latin rule, the city retained its bilingual, bicultural heritage.

Echoes of northern stonework in southern limestone

The materials of Bari’s Romanesque art also tell a story of adaptation. Unlike northern Italy, where brick often dominated, Apulia had access to high-quality limestone—dense, fine-grained, and capable of holding intricate detail. The creamy-white stone used in Bari’s churches allowed sculptors to mimic the effects of northern marble, but with a softness more suited to subtle reliefs than bold three-dimensional forms.

Northern influence came not only in iconography but also in technique. Stonecutters from Lombardy, Burgundy, and even Normandy arrived in southern Italy, some as part of itinerant workshops. In Bari, they encountered a local tradition steeped in Byzantine habits—more attuned to pattern than to mass. The resulting fusion is visible in works like the ambo (pulpit) of San Nicola, with its delicately carved lions and interlace bands, or the cloister capitals of nearby monastic complexes, where biblical scenes unfold in miniature beneath leafy volutes.

Yet the most unexpected artistic inheritance of this period may lie in the reuse of classical motifs. Norman patrons, despite their martial instincts, displayed a pronounced taste for antique forms. In Bari and nearby Bitonto, sculptors incorporated acanthus leaves, Ionic volutes, and even fragments of Roman sarcophagi into their new constructions. These were not simply acts of recycling—they were gestures of legitimacy. By quoting Rome, Norman rulers sought to position themselves as heirs to a deeper, more universal authority.

One striking example is the portal of San Sabino, where a reused Roman column drum has been carved with a Latin inscription commemorating the church’s rededication under Norman rule. The message is clear: the past is not overthrown, but appropriated.

Bari’s Romanesque phase, then, was not a rejection of its earlier Byzantine self, but a complex layering of new symbols atop older foundations. Under Norman patronage, the city embraced an art of thickness—thick walls, thick capitals, thick meanings. It was an art meant to endure.

The sculptures of Bari do not whisper. They declare. They remind. They judge. And they remain, their edges worn by wind and time but still sharp enough to catch the eye—and perhaps the conscience—of those who pass beneath them.

The Silent Influence of Byzantium

Not all legacies arrive loudly. While the Normans reshaped Bari’s skyline with their assertive Romanesque churches and public monuments, the aesthetic memory of Byzantium never disappeared—it retreated into shadows, niches, and side chapels, whispering its continuity through iconography, liturgy, and ornament. Bari had been a Byzantine city for centuries, its administration, faith, and art shaped by Constantinople. Even after the Norman conquest, this deep cultural sediment did not evaporate. It persisted quietly, often in devotional spaces where the line between art and prayer dissolved.

Icons, gold leaf, and hybrid liturgies

The clearest expression of Byzantine artistic influence in Bari lies in its devotional imagery—particularly its use of icons. Though many original Byzantine works have been lost or overwritten by later interventions, a few extraordinary examples survive. These are not paintings in the Western sense, but devotional objects steeped in theology, made to channel presence rather than illustrate doctrine.

One of the most striking is the 13th-century Madonna Odegitria, housed in the Basilica di San Nicola. Painted on wood in tempera and gold, the Virgin holds the Christ child while pointing toward him with her right hand—the classic “she who shows the way” gesture of Byzantine iconography. Unlike Western Madonnas, who often display tender or naturalistic emotion, this figure is hieratic, frontal, and stylized. Her gaze meets the viewer without concession, her gold background collapsing time and space into sacred stillness.

The Odegitria icon is more than a surviving relic; it is a clue to Bari’s dual liturgical life. For centuries, the Greek rite persisted alongside the Latin rite, especially in churches and chapels built before the Norman consolidation of ecclesiastical authority. In some parishes, Greek was spoken at Mass well into the 14th century. This bilingualism shaped not just music and scripture, but also the visual field. Bilingual inscriptions, hybrid saints (venerated in both traditions), and painted cycles that combined Eastern stylization with Western narrative rhythm appeared throughout the region.

Several lesser-known churches in the Bari hinterland—such as Santa Maria del Buon Consiglio and San Michele Arcangelo—contain fragments of wall painting in a Byzantine idiom: bold contours, frontal figures, saturated reds and blues, and minimal background perspective. These frescoes, often tucked away in apses or crypts, testify to a population that did not abandon its inherited visual grammar even under Latin rule.

Three aspects of this continued Byzantine tradition stand out:

- A sustained preference for icon-like imagery in private chapels and side altars.

- The persistence of gold-ground paintings well after they had gone out of fashion in central Italy.

- The use of sacred geometry—circles, stars, and squares—as structuring principles in church decoration.

This was not a frozen style but a living one, subtly adapting to new pressures while retaining its core convictions.

The cloisters and mosaic traditions

If the interior spaces of Bari’s churches preserve a Byzantine spirit through painted icons, the city’s monastic architecture holds another legacy: the decorative vocabulary of Eastern cloisters. Though few cloisters survive intact today, archaeological traces and regional examples suggest that Bari once had a network of small monastic complexes whose spatial design echoed Byzantine models.

In these cloisters, the focus was not on grandeur but on order and reflection. Arcaded walkways framed interior gardens, where columns were often reused from older Roman or Byzantine buildings. The capitals—some carved, some simple drums—offered no grand narrative, but they participated in a contemplative rhythm that mirrored monastic life. The very act of walking through such spaces was aestheticized: a procession of stone, shadow, and silence.

Mosaic, another hallmark of Byzantine art, appears only sporadically in Bari, but its influence can be felt in the decorative schemes of nearby cathedrals such as Otranto and Trani. In Bari itself, floors of small inlaid stone tiles—opus sectile—offer a local reinterpretation of mosaic technique. Geometric patterns of red porphyry, green serpentine, and white marble form stylized floral and cosmic motifs, particularly in the crypts. These floors were meant to be read with the feet, not the eyes—a Byzantine idea filtered through a Latin lens.

One particularly haunting example lies in the crypt of San Nicola, where the low ceiling and dense colonnade amplify the sensory impact of the floor beneath. As pilgrims shuffle toward the saint’s tomb, they move across stars, interlocking circles, and labyrinthine borders—abstract forms designed to align the body with sacred order.

This quiet geometry contrasts with the more sculptural drama of the Romanesque naves above. Where the Latin aesthetic shouted, the Byzantine one hummed. The two were not at odds; they were partners in a dialogue of silence and sound, vision and movement.

Greek painters in Apulian churches

Bari’s role as a port also enabled the continued arrival of Greek-speaking artists and craftsmen well into the 13th century. Monastic records and notarial contracts from the period mention painters from Thessaloniki, Naxos, and Epirus working on commissions in Apulia. These itinerant artists brought with them the techniques of egg tempera, the theology of the icon, and an aesthetic sensibility steeped in Byzantine court culture.

In the crypt of the former church of Santa Maria del Buonconsiglio, a faded but evocative fresco shows a standing saint—probably Basil or Nicholas—rendered in a stiff frontal pose, framed by an aureole, with oversized eyes and a stylized beard. Though damaged, the work displays telltale signs of a Greek-trained hand: fine incised lines to mark folds, dense pigment layers built from mineral pigments, and a deliberate lack of illusionism.

Elsewhere in the region, workshops began to blend Byzantine and Western styles. A Madonna from nearby Bitetto, for instance, combines the gold background and flat modeling of the icon with the flowing hair and downcast eyes more typical of Gothic painting. These are not pastiches but syntheses—evidence of a visual world in which categories were fluid, and painters moved easily between idioms depending on patron and purpose.

A few intriguing details underscore this hybridity:

- Greek and Latin script sometimes appear side-by-side in church inscriptions.

- Some saints are given both Eastern and Western iconographic attributes—for example, Nicholas with both a bishop’s crozier and the Greek omophorion.

- Architectural spaces are designed with both altar screens (Eastern) and nave altars (Western), allowing liturgies to shift as needed.

This ability to accommodate multiple visual and liturgical languages is one of the defining features of Bari’s art during this period. It did not assert a single aesthetic identity but held space for many—layered, overlapping, and at times contradictory.

Bari’s Byzantine heritage, then, did not vanish under Norman limestone. It persisted beneath, beside, and within it—quiet, persistent, and generative. It shaped how people saw the sacred, how they moved through space, how they imagined holiness. Its silence was not absence, but influence refined into restraint.

Swabian Shadows: Frederick II and the Art of Power

In the early 13th century, the skies over Bari darkened with a new imperial presence. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen—King of Sicily, Holy Roman Emperor, and self-styled heir to both Charlemagne and Augustus—brought with him an entirely different vision of what art should do. Unlike the Normans, whose buildings declared religious authority in stone, Frederick pursued an aesthetic of intellect and control. In Bari and across Apulia, he created a visual and architectural regime not of excess, but of clarity, precision, and political symbolism. His was not a patronage of piety, but of sovereignty. The city, already layered with Latin and Byzantine art, now became a canvas for a distinctly Swabian ideal: imperial, rational, and multilingual.

Castello Svevo and the aesthetics of control

The most conspicuous mark of Frederick’s reign in Bari is the Castello Svevo—a brooding fortress rising just west of the old city, where the land meets the sea. First built by the Normans in the late 12th century, the castle was significantly rebuilt and expanded by Frederick after 1233. Unlike the flamboyant cathedrals or richly ornamented churches of earlier rulers, the Swabian castle speaks in the spare, rectilinear language of power. Its thick bastions, massive curtain walls, and unadorned geometry project not beauty but dominance.

Though military in function, the castle was also a statement of presence. Frederick’s statecraft was visual as much as legal. A polyglot ruler fluent in Latin, Greek, and Arabic, he envisioned his southern territories as a model of imperial order—a domain ruled by law, culture, and architectural logic. The Castello Svevo in Bari, with its symmetrical layout and strategic placement overlooking the harbor, functioned as a civic eye, watching both the city and the sea.

Frederick’s architectural projects across Apulia—including the famous Castel del Monte—share a common language: severe symmetry, controlled proportions, and a resistance to overt religious symbolism. Bari’s castle, though less geometrically radical than Castel del Monte, participates in this aesthetic of surveillance and order. Its internal courtyard, arcaded on multiple levels, suggests not merely a barracks but a place of bureaucratic administration, possibly even imperial residence.

Within the castle’s interior, few decorative elements survive, but traces of Gothic ribbing and pointed arches indicate a stylistic evolution from the earlier Romanesque bulk to something more linear and systematized. This was Gothic not as theological yearning, but as architectural rationalism—stripped of ornament, sharpened into policy.

Three spatial features reveal Frederick’s particular intentions:

- A gatehouse designed not merely for defense but for ceremonial entry.

- Elevated walkways that allowed guards to monitor the city and the port simultaneously.

- A balanced plan that aligned with prevailing winds and solar angles—functional, but also symbolic of imperial harmony.

The castle thus becomes not just a building, but a thesis: an argument for rule by intellect, stone, and symmetry.

Classical revival under a multilingual court

Frederick’s fascination with antiquity was not affectation—it was a governing principle. Unlike many medieval monarchs, who regarded the classical past with vague reverence, he studied it systematically. His court in Palermo was known for its scholars, translators, and scientists. Bari, too, came under the orbit of this classical revival, particularly through legal reform and architectural order.

Though the city was not the cultural epicenter of Frederick’s rule—that honor fell to Palermo and Foggia—it absorbed the currents of his intellectual project. In Bari’s public spaces and legal institutions, the influence of Roman ideals became palpable. Legal codes such as the Liber Augustalis, promulgated by Frederick in 1231, were circulated and interpreted here. While not strictly visual, these texts reshaped the city’s built environment by imposing order, standardizing measurements, and linking civic space to imperial authority.

In architecture, this manifested as a return to classical norms—not decorative Corinthian columns, but the deeper grammar of axiality, module, and hierarchy. Churches renovated during this period—such as the Cattedrale di San Sabino—began to exhibit more regularized spacing, pointed arches, and a restrained sculptural vocabulary. These were not flamboyant Gothic buildings in the northern sense; they were Apulian hybrids: orderly, composed, and slightly austere.

Within this visual language, Frederick cultivated a network of artists and scholars who worked across linguistic and cultural lines. Greek icon painters, Latin masons, Arab astronomers, and Jewish translators all contributed to a culture in which artistic form became a metaphor for rational rule.

Three micro-narratives from Bari illustrate this convergence:

- A Greek-speaking iconographer, documented in cathedral records, commissioned to repaint a chapel in a style both legible to pilgrims and in keeping with Latin liturgical norms.

- A Latin notary tasked with copying imperial edicts alongside astronomical diagrams—a visual practice blurring law and cosmology.

- A visiting emissary from the Kingdom of Aragon who described Bari’s harbor fortifications as “severe, but like a Roman camp—perfect in their rightness.”

Frederick’s court, in this sense, was less a cultural melting pot than a well-regulated mosaic: diverse pieces held in place by force and vision.

Legal codes and calligraphy as visual systems

In Frederick’s southern Italy, law itself became a kind of art. The Liber Augustalis—officially the Constitutions of Melfi—was not only a legal code but a visual object. Manuscripts of the law were carefully copied in formalized Latin scripts, embellished with marginalia, and stored in ecclesiastical and civic archives. Bari, as a significant city in the imperial kingdom, held such manuscripts and was involved in their dissemination.

Calligraphy in this context was not decorative. It was declarative. The scripts used—Carolingian minuscule, later hybridized with Gothic elements—were designed for clarity and uniformity. Each letter, each margin, reinforced the idea of imperial law as both eternal and visible. Public readings of the code were held in civic spaces, transforming legal language into a kind of performative art.

In churches, too, inscriptions shifted in character. Earlier epigraphy often mingled Greek and Latin, with variable letterforms and occasional misspellings. Under Swabian administration, inscriptions grew more uniform, more monumental, more carefully integrated into architecture. The language of command entered stone. Even donor plaques became more rigid, naming not only benefactors but also the reigning emperor—lest anyone forget under whose aegis the work was done.

This aesthetic of authority extended even into absences. Unlike the earlier Norman and Byzantine periods, the Swabian phase in Bari did not produce much in the way of devotional art. Few altarpieces, no grand cycles of frescoes, little gilded pageantry. The art of Frederick’s reign was not directed upward, toward heaven, but outward—toward order, territory, law.

Bari under Frederick II became a city of shadows: of watchtowers and parchment, of geometry and policy. Its art, often less visible than in earlier centuries, was no less powerful. It whispered discipline. It spoke in lines and margins. It endured not in paint, but in plan.

Renaissance without Florence: Apulian Humanism and Its Limits

The Renaissance, as popularly imagined, unfurled across the Italian peninsula like a seamless golden tide—Florentine perspective, Roman classicism, Venetian color, all reaching the provinces in a rush of brilliance. But Bari, like much of southern Italy, tells a different story. Here, humanist ideals arrived not with a burst of pictorial revolution, but with books, letters, and the slow migration of scholars. The city’s Renaissance was quieter, more intellectual than visual, and shaped by the constraints of geography, politics, and patronage. It was a period of cultivated potential—and notable limitations.

Regional painters in a Florentine world

By the mid-15th century, Renaissance innovations in painting—naturalistic figures, linear perspective, and atmospheric depth—had begun to spread from central Italy. Yet Bari remained on the periphery of these movements. No native school of painting emerged to rival the Florentines or Umbrians. Instead, the city relied on itinerant artists, often trained in Naples or the Marche, who brought diluted versions of central Italian styles to southern patrons.

These artists worked largely on commission for churches and confraternities, producing altarpieces and devotional panels that combined Gothic survivals with timid gestures toward Renaissance innovation. Figures grew more volumetric, gold leaf gave way to landscape backgrounds, but the leap to full pictorial illusionism was halting. Perspective, when it appeared, was schematic. Anatomy followed old formulas. Colors, though often vivid, were deployed without the subtle modulation seen in the north.

One representative example is the 15th-century triptych in the church of San Marco dei Veneziani. Its central Madonna and Child are flanked by saints rendered in a stiff, frontal manner. The Virgin sits on a throne vaguely recalling Brunelleschian architecture, but the proportions are off, the spatial recession hesitant. Still, there is warmth in the faces, delicacy in the drapery folds—a desire, if not the full capacity, to emulate Tuscan refinement.

Bari’s painters operated under three significant constraints:

- Limited access to major artistic workshops or formal training academies.

- A local clientele more concerned with devotion than innovation.

- Intermittent patronage interrupted by political instability and shifting allegiances.

This did not mean Bari lacked talent—only that it developed differently. Where central Italy produced great pictorial cycles, Bari fostered a more textual, rhetorical Renaissance.

Libraries, Latin, and the art of manuscripts

If painting lagged behind, the intellectual currents of humanism found firmer footing in Bari’s scriptoria and private studies. The rediscovery of classical texts, the revival of Ciceronian Latin, and the emulation of Roman moral ideals all took hold here—not through frescoes, but through parchment. Bari’s Renaissance was, above all, philological.

Cathedral and monastic libraries became centers of humanist activity. Clerics trained in Naples or Rome returned to Bari bearing not paintings, but codices—Livy, Seneca, Virgil—carefully copied and annotated. A few of these manuscripts, now held in the Archivio Capitolare and other ecclesiastical collections, show a refined aesthetic: wide margins, elegant humanist script, and restrained illumination. Decorative initials echo Roman models, using acanthus scrolls and classical urns, but with a minimalism that reflects both Apulian sobriety and monastic discipline.

Private collectors also emerged. Wealthy merchants and minor nobles, many of whom had children studying law or theology in Naples, began to commission manuscripts for personal libraries. These included not only Latin classics, but also legal texts, devotional commentaries, and scientific treatises. In this milieu, the Renaissance book was both a status symbol and an intellectual tool.

One merchant family, the Del Buono, maintained a small scriptorium in the early 16th century that specialized in copying works of Augustine and Boethius. Their patronage reveals a distinctly southern approach to Renaissance culture: conservative, ecclesiastical, and textual. Art here was not painted on walls, but written in margins.

Three particularly vivid elements of Bari’s manuscript culture stand out:

- A consistent use of Greek alongside Latin in theological texts, reflecting the region’s bilingual heritage.

- Marginal glosses that mix scholastic commentary with personal reflection—evidence of active, not passive, reading.

- Decorative schemes that eschew gold and purple in favor of black ink and red rubrication—austerity as elegance.

This was a humanism of the pen, not the palette.

Bari’s intellectual merchants and their artistic commissions

The most interesting Renaissance patrons in Bari were not always bishops or dukes, but merchants—men with one foot in commerce and another in culture. Their patronage shaped not only what was made, but how and why. These were not Medici commissioning Botticelli, but grain exporters sponsoring chapels, or olive oil magnates ordering altarpieces for their family tombs. Their motivations were deeply personal: salvation, legacy, local status.

Take the example of Matteo Sparano, a spice trader whose travels took him to Venice, Thessaloniki, and Alexandria. In 1498, he endowed a chapel in the church of San Gregorio, specifying in his will that it should include a painted altarpiece of the Madonna and Saints, “in the style now fashionable in Naples.” The result, likely executed by a local artist trained in the Neapolitan circle of Colantonio, is a staid but competent panel. It lacks the sophistication of central Italian works, but it asserts Sparano’s cosmopolitan identity—a man who prayed in Bari but thought in the broader Mediterranean.

Other merchant patrons, such as the Alfieri and Sersale families, commissioned funerary monuments, choir stalls, and pulpits. Their aesthetic leaned conservative—no nude figures, no mythological themes—but their desire for permanence, for stone and image to bear their name into the future, aligns with the deeper aims of Renaissance art.

These patrons also supported music, education, and architecture. Some helped fund the rebuilding of church apses or the repair of bell towers. Their wealth enabled modest renovations, even when large-scale transformation eluded the city.

Bari’s Renaissance, then, was shaped not by visionary artists, but by practical humanists—people who saw art as one part of a larger intellectual and spiritual life. They may not have invented new forms, but they cultivated meaning in the margins.

This was a Renaissance of thresholds: between old and new, Latin and Greek, Florentine aspiration and Apulian restraint. It never found its Michelangelo or its Raphael. But it found a voice—in script, in stone, in quiet paintings—that still murmurs through the narrow streets and dusty archives of Bari.

Baroque in the South: Devotion, Drama, and Domestic Ornament

In the 17th century, Bari’s art world surged back into motion. Where the Renaissance had unfolded with intellectual reserve, the Baroque arrived like a storm—opulent, theatrical, and unapologetically emotional. Spurred by the Counter-Reformation and supported by new patterns of patronage, Bari’s churches blossomed with gilded altars, swirling frescoes, and sculpted saints caught in ecstatic gestures. But unlike Rome or Naples, whose Baroque identities were shaped by papal mandates or royal courts, Bari’s version of the style was more dispersed. It flowered in chapels, processions, sacristies, and salons—in the intimate spaces where faith met spectacle.

Theatrical altars and golden chapels

Walk into the Church of San Gaetano in Bari’s historic center, and the visual vocabulary of the Baroque announces itself immediately: twisted Solomonic columns wrapped in gold leaf, cascading drapery sculpted from marble, cherubs peering through rays of painted light. The high altar explodes with vertical momentum, drawing the eye upward toward a dome ringed with frescoed clouds. Here, the architecture does not simply frame the sacred—it performs it.

These altars were not static objects; they were dynamic stages. Designed to animate the Mass, especially during major feast days, they emphasized presence, transformation, and divine intimacy. The materials—gold, colored marble, painted wood—created a synesthetic experience, amplifying the scent of incense and the sound of liturgy with dazzling visual effects. In this world, salvation was not abstract. It shimmered.

The dominant Baroque elements in Bari’s churches include:

- Gilded wooden altars intricately carved and often polychromed.

- Tabernacles framed by theatrical niches and framed with sculptural angels.

- Complex ceiling frescoes that merge architecture with illusionistic space.

One of the most compelling examples is the Church of Santa Teresa dei Maschi, completed in the late 17th century. Its barrel-vaulted nave is covered in a fresco cycle by Carlo Rosa, a local artist trained in Naples. The scenes—episodes from the life of Saint Teresa—are executed with spiraling motion, anatomical exaggeration, and a chromatic palette heavy in blues and ochres. Rosa’s work reveals the south’s deep connection to Neapolitan visual culture, while still rooting itself in local devotions and saints.

Local saints, lavish processions, and visual spectacle

Baroque art in Bari was not confined to interiors. It spilled into the streets during elaborate religious processions that turned the city itself into a stage. The Feast of Saint Nicholas, already centuries old, became more theatrical, with wooden statues paraded through the city, dressed in silk vestments and crowned with silver halos. These images were often housed in special chapels, removed only on high holy days. Their faces—typically serene but solemn—were painted with real human hair, glass eyes, and articulated joints that allowed arms to be raised or lowered in gestures of benediction or suffering.

These processional statues blurred the line between sculpture and puppet. They were not art objects in the museum sense, but vessels of presence—carried, bowed to, kissed, and sometimes wept before. The artistry lay not only in their craftsmanship but in their use: the choreography of bodies in public space, the staging of penance and exaltation.

Particularly notable is the Cristo Morto procession on Good Friday, during which a life-size statue of the dead Christ is carried in silence through the winding streets of Bari Vecchia. Sculpted in the 18th century, the figure is pale, emaciated, and painted with agonizing detail—blood, wounds, contorted limbs. The silence of the procession serves as a frame, amplifying the statue’s affective power.

Theatricality in southern Baroque art extended to sound and motion. Bells, drums, chanting—these aural elements activated the visual. The procession became a multisensory liturgy in motion, blending art, devotion, and social ritual.

Three elements made these events distinctly Barese:

- The integration of maritime themes—ships, anchors, and sailors’ devotions—into iconography.

- The participation of lay confraternities who commissioned and maintained many of the statues.

- The spatial use of Bari’s urban geography—tight alleys, open piazzas, and coastal overlooks—as part of the sacred dramaturgy.

Baroque art here was not just in churches—it was in the air, the movement, the communal gaze.

Murals, martyrdom, and the persistence of faith

While Neapolitan artists shaped much of Bari’s Baroque style, local painters also emerged, adapting the broader idiom to regional tastes. The Rosa family, including Carlo Rosa and his son Francesco, dominated the mid- to late-17th century. Their workshop produced altar paintings, ceiling frescoes, and private devotional works that balanced emotional intensity with compositional discipline.

A frequent subject in this period was martyrdom—scenes of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows, Saint Lucy holding her plucked eyes, Saint Catherine on the breaking wheel. These were not merely grotesque—they were affective tools. Designed to provoke empathy and repentance, they reminded viewers of the cost of faith. Blood, when painted, gleamed.

One vivid example is the altarpiece of Saint Bartholomew in the Church of San Giuseppe. The saint, traditionally depicted being flayed, is here shown mid-torment, his eyes turned heavenward even as his skin is pulled from his limbs. The executioner’s arm arcs in frozen motion, while a cherub descends from above with a crown of martyrdom. The lighting—harsh chiaroscuro—dramatizes the pain but also the transcendence. It is theater, theology, and psychology in one frame.

Yet not all Baroque painting in Bari was violent. Domestic piety found its own forms. Small oil paintings of the Virgin and Child, the Holy Family, and the Immaculate Conception were commissioned for bedrooms, kitchens, and stairwells. Often unsigned, these works reveal a vernacular religiosity—intimate, tender, and deeply rooted in daily life.

Three traits characterize these domestic Baroque images:

- A focus on maternal tenderness, with Mary shown breastfeeding or cradling the infant Christ.

- The use of warm, earthy palettes—ochres, siennas, soft reds—distinct from courtly brilliance.

- Quiet iconographic innovations, such as Joseph shown in contemplative repose or angels cleaning household objects.

This is the Baroque as lived experience, not public spectacle. An art not of cathedrals, but of corners.

Baroque Bari, then, was many things at once: ecstatic and introspective, gilded and bloodied, public and private. Its drama was not imported wholesale from Rome or Naples, but shaped by local hands, needs, and devotions. It made room for both the grand gesture and the quiet gaze.

Even today, amid the pizzerias and shuttered balconies of Bari Vecchia, one can find remnants of this Baroque world: a cracked stucco cherub above a doorway, a faded fresco behind an altar cloth, a processional statue wrapped in linen, waiting for its annual return to the streets. These are not relics—they are resting performers, part of a tradition that never fully retreated behind museum glass.

Napoleonic Reforms and the Neoclassical Wave

The 19th century began in Bari not with a flourish of civic pride but with disruption. The Napoleonic occupation of southern Italy, while brief in its direct military presence, upended centuries of ecclesiastical power, altered civic institutions, and redefined the role of art in public life. Churches were closed or repurposed, monastic orders were suppressed, and religious artworks were seized or destroyed. Yet amid this tumult, a new aesthetic emerged—Neoclassicism—rooted in Enlightenment ideals and visual restraint. In Bari, it offered not just a stylistic shift, but a way of rebuilding identity in the ruins of religious dominance.

Secularization and the art of absence

When French forces and their local allies assumed control of the Kingdom of Naples in 1806, they brought with them a program of secular modernization that struck at the heart of Bari’s artistic infrastructure. Over the next decade, dozens of monasteries and religious houses across Apulia were suppressed. Their assets—books, artworks, land—were seized by the state. Churches once vibrant with Baroque devotion fell silent, some shuttered entirely, others stripped of liturgical furnishings and altarpieces.

In Bari, the impact was stark. The Monastery of Santa Scolastica, one of the city’s oldest and most artistically rich, was deconsecrated. Its cloisters became storage spaces; its frescoes, neglected and water-damaged, began to peel. Other churches were divided: sacristies repurposed as offices, chapels turned into military quarters. The once-ubiquitous sight of saints and martyrs in paint and wood gave way to blank walls, boarded niches, and empty frames.

This absence became a kind of unintended aesthetic. Visitors to Bari in the early 19th century noted the eerie quiet of its sacred spaces. One English traveler in 1812 described the Church of San Domenico as “a great cavern of plaster and forgotten angels,” its altar removed, its ceiling frescoes graying in the humidity. Bari, a city whose religious culture had been almost entirely visual, now confronted a new paradigm: the blankness of modernity.

Yet this visual silence was not without its own expressive power. The loss of art created a space for reflection—and, in time, reinvention.

French administration and civic architecture

While the religious sphere contracted, the civic one expanded. The Napoleonic reforms included the introduction of centralized bureaucratic institutions, a new legal code, and the reorganization of municipal governance. These changes required buildings: courthouses, schools, military offices, archives. Into this vacuum stepped the Neoclassical style—precise, rational, and evocative of republican Rome.

In Bari, this new aesthetic found its clearest expression in the reconstruction and expansion of public buildings. The Teatro Piccinni, completed in 1854 and named after the local-born composer Niccolò Piccinni, became the city’s cultural centerpiece. Designed with a sober Neoclassical façade—symmetrical columns, triangular pediment, evenly spaced windows—it embodied the new civic ideals: enlightenment, order, public reason.

Other Neoclassical interventions were more modest but equally symbolic. The Piazza del Ferrarese was restructured to open more directly toward the sea, creating a ceremonial urban axis. Government buildings adopted clean lines, rusticated bases, and simplified cornices. The new visual language was self-consciously non-religious, even anti-clerical. Where once saints had watched from pediments and facades, now sat allegories of justice, commerce, and agriculture—idealized, secular, and rendered in pale local stone.

This architectural transformation was neither total nor uncontested. Bari’s population remained deeply attached to its religious heritage. Many citizens viewed the new Neoclassical structures as foreign impositions, lacking warmth or spirit. But over time, as the old ecclesiastical elite faded from public life, these buildings became the new sites of ritual: not masses, but court sessions; not processions, but operas.

Three architectural characteristics defined Bari’s Neoclassical civic spaces:

- The extensive use of local limestone, cut into regular blocks to mimic Roman ashlar.

- The adoption of Latin inscriptions extolling civic virtue and legal order.

- The introduction of interior painted decoration based on Roman motifs—laurel wreaths, festoons, and trompe-l’oeil columns.

It was a vision of a modern Bari, rooted in the clarity of the ancients but purged of their saints.

New academies and an old provincial identity

Perhaps the most lasting effect of the Napoleonic era in Bari was educational. In keeping with Enlightenment ideals, new schools, lyceums, and technical academies were established, many of them housed in former religious buildings. These institutions fostered a generation of secular intellectuals, civil servants, and—importantly—artists.

The Accademia di Belle Arti in Bari, though not formally established until the late 19th century, had its antecedents in the drawing schools and technical workshops that proliferated in this period. These academies prioritized draftsmanship, anatomy, and classical form. Students copied plaster casts of Greco-Roman statues, studied geometry, and were taught to disdain the “excesses” of the Baroque.

Yet for all this pedagogical rigor, Bari remained a provincial city, and its artists often struggled for recognition. They sent works to exhibitions in Naples and Rome, but seldom received commissions of national significance. As a result, Neoclassical art in Bari tended toward the modest: commemorative plaques, marble busts, and civic allegories in watercolor.

Still, these works bear the imprint of the period’s ambitions. One notable figure is Francesco Netti (1832–1894), a painter from nearby Santeramo in Colle who trained in Naples but returned often to Apulia. Though his mature work leaned toward social realism, his early training in Neoclassicism is evident in his careful modeling, subdued palette, and idealized figuration. His trajectory mirrors that of Bari itself: shaped by Enlightenment form, but increasingly drawn to the messier realities of southern life.

In this transitional moment, three artistic tendencies coexisted uneasily:

- A Neoclassical idealism rooted in academic training and civic decorum.

- A nostalgic attachment to Baroque religious forms, especially in private devotion.

- A nascent realist impulse, increasingly responsive to local landscape and labor.

Bari’s 19th-century art thus bore the marks of both rupture and continuity. It emerged from the wreckage of church power, learned to speak in the dry vocabulary of law and reason, but never fully abandoned its emotional roots.

The Neoclassical façades that line Bari’s 19th-century streets may appear austere today, but they represent an audacious wager: that a city could remake itself not through saints and miracles, but through marble columns, education, and the dream of reason made visible. It was a noble experiment—partially realized, quietly enduring.

Modernism on the Margins: 19th-Century Shifts

As the 19th century drew to a close, Bari stood at a complicated intersection. The city had survived Napoleonic secularization, adapted to the measured clarity of Neoclassicism, and begun to educate a class of technically trained artists and architects. Yet compared to the north—Milan, Florence, even Naples—Bari remained culturally peripheral. Modernism, when it came, did not sweep in with utopian fervor or radical manifestos. It trickled, refracted through the tastes of middle-class patrons, the ambitions of regional painters, and the shifting needs of a port city adapting to steam, rail, and bureaucracy.

Port expansion and the industrial gaze

Bari’s physical transformation in the late 19th century was driven less by aesthetics than by infrastructure. The port, historically a locus of pilgrimage and mercantile exchange, was expanded dramatically between the 1850s and 1910s. New piers, customs houses, and warehouses appeared, shaped not by classical harmony but by efficiency and steel. The arrival of the railway in 1865 further accelerated Bari’s integration into the national economy. And with rail and sea came a new kind of visual language—pragmatic, mechanical, and horizontal.

Architecture responded accordingly. The old town (Bari Vecchia) remained densely packed and visually conservative, but the Murattiano district, named after Joachim Murat (Napoleon’s brother-in-law), offered a clean grid of boulevards, arcades, and apartment blocks. It was a laboratory for civic modernity, where gas lamps, telegraph lines, and cafés converged with new stylistic flourishes: Art Nouveau ironwork, eclecticist façades, and imported marbles.

In this new quarter, civic pride manifested less in monumental churches and more in rational buildings: train stations, post offices, banks. The Palazzo della Provincia, completed in 1935 but based on earlier 19th-century plans, bears the imprint of this functional elegance—clean lines, regular fenestration, discreet classical motifs reduced to geometry.

This industrialized urbanism altered the very gaze of Bari’s citizens. The horizon—once framed by domes and bell towers—now included cranes, railcars, and the silhouettes of passenger liners. The visual rhythm of the city shifted from vertical sacrality to horizontal expansion.

Three architectural features captured this shift:

- Façades in local stone punctuated by iron balconies and cornices in floral ironwork.

- Interior courtyards designed for ventilation and light, responding to new hygiene ideals.

- Public buildings with restrained ornament and an emphasis on symmetry, proportion, and accessibility.

This was not yet avant-garde architecture, but it was thoroughly modern in its intentions.

Painters of the quotidian and the Apulian countryside

While the city transformed under the pressures of industry and governance, painters turned increasingly to the surrounding countryside. Apulia’s olive groves, wheat fields, and stone farmhouses became the favored subjects of a generation of regional realists who sought to depict the labor, sunlight, and silence of the southern land without sentimentality or grandeur.

Chief among these was Francesco Netti, whose early Neoclassical training gave way to a more naturalistic vision shaped by his exposure to French realism and the School of Posillipo in Naples. His painting La morte del contadino (The Death of the Peasant), completed in the 1870s, captures a stark moment in a rural household: the dying figure laid out on a wooden bed, his family gathered in subdued grief, the ochre walls bare except for a crucifix. The brushwork is loose but controlled; the palette, somber. The painting is not dramatic—it is observant. And that is its modernism.

Netti and his contemporaries—such as Giuseppe De Nittis (from nearby Barletta)—forged a southern alternative to the grand historical or mythological painting dominant in academic circles. Their art was grounded in the specific: heat, dust, fatigue, gesture. In Bari, this realism never crystallized into a formal “school,” but it permeated studios and galleries, offering a human scale to an increasingly impersonal urban reality.

Some recurring motifs in late 19th-century Apulian painting include:

- Sun-bleached courtyards framed by dry stone walls and fig trees.

- Women engaged in domestic labor—kneading bread, spinning wool, carrying water.

- Agricultural scenes of sowing, threshing, and resting—always with a subdued emotional register.

Though regional in origin, these paintings aligned Bari with wider European trends: the Barbizon School in France, the Macchiaioli in Tuscany, the Munich realists in Germany. They suggested that the modern need not be urban, nor the avant-garde necessarily radical. It could be slow, local, and clear-eyed.

Photography, postcards, and Bari’s new image

By the 1880s, a new medium began to reshape how Bari saw itself—and how it was seen: photography. Studios sprang up across the Murattiano district, offering portraits, architectural studies, and scenic views for both locals and tourists. These images circulated widely in the form of postcards, commercial prints, and illustrated journals.

Photographers like Angelo Ceglie and Luigi Galeandro documented not only the city’s boulevards and harbor, but also its people. Street vendors, fishermen, women in traditional dress, children playing along the Lungomare—all became subjects in a new visual archive. Unlike earlier portraiture, which isolated figures against backdrops of wealth or fantasy, these photographs embedded their subjects in place and circumstance.

One iconic image from around 1905 shows a barefoot boy balancing a basket of octopus on his head, framed by the rough stone of the old city behind him. The light is harsh, the composition loose. But the image speaks volumes about class, survival, and identity. Bari was no longer just a port of saints and soldiers—it was a city of modern bodies caught between tradition and transformation.

Three innovations defined Bari’s photographic modernism:

- The democratization of image-making through affordable portraits and postcards.

- The emergence of urban documentary photography as a form of social testimony.

- The use of light and shadow to dramatize texture and architecture in ways painting could not.

Photography in Bari served multiple roles: commercial, civic, personal, political. It was art, but also evidence. And in its proliferation, it marked a decisive turn: the image was no longer sacred, unique, or fixed. It was reproducible, mobile, ephemeral. A new visual economy had begun.

This transitional period in Bari’s art history—between the Baroque and the avant-garde, between fresco and film—offers no single style or genius figure. Instead, it reveals a network of adaptations: to industrialization, to secular civic life, to emerging technologies. Modernism here was not heroic—it was partial, adaptive, marginal. But it was real. And it left its mark in canvas, stone, glass, and silver nitrate.

Fascist Urbanism and the Architecture of Authority

In the 1920s and ’30s, Bari became an unlikely stage for Italy’s authoritarian vision of modernity. Under Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime, the city—long dismissed as a sleepy provincial port—was reimagined as a gateway to the East, a model of Mediterranean discipline, and a monument to state power. Fascism brought not only speeches and uniforms but bulldozers, masterplans, and an architectural language that fused classical clarity with ideological force. In Bari, this transformation left its deepest imprint in stone and space, producing some of the most imposing urban interventions in its history.

The regime’s imprint on city planning

Fascism’s relationship with architecture was never purely aesthetic. It was strategic. Cities were to be remade in the image of the regime: rational, legible, and ordered according to a mythology of Roman grandeur and Italian destiny. In Bari, this agenda took the form of dramatic urban restructuring that targeted both the symbolic heart and the physical periphery of the city.

The plan was twofold. First, to create monumental new zones that could host parades, exhibitions, and bureaucracies. Second, to cleanse the urban fabric of anything considered chaotic, unmodern, or “degenerate”—a euphemism that often masked class and political violence. In practical terms, this meant the demolition of sections of Bari Vecchia and the expansion of the Murattiano district with broad boulevards, rationalist buildings, and vast public spaces.

The most emblematic development was the Fiera del Levante, founded in 1930 as a grand trade fair intended to link Italy’s economy with those of the Balkans and the wider Mediterranean. Designed by architects such as Concezio Petrucci and Cesare Bazzani, the fairgrounds sprawled across the city’s western edge, presenting pavilions in a stripped classical idiom: symmetrical facades, clean verticals, minimal ornament, and a clear visual hierarchy.

Nearby, the Lungomare Nazario Sauro was extended and refitted with Fascist-era balustrades, lamp posts, and vistas. A new maritime station, clad in white stone and framed by rigid arcades, served as both transportation hub and architectural manifesto. Bari was being rewritten—as if history could be carved over with limestone.

Three spatial strategies underpinned this transformation:

- Axis and vista: Long, straight streets framing key monuments in the visual field.

- Hierarchy of function: Zoning that separated government, commerce, and housing into disciplined sectors.

- Symbolic voids: Large public squares and esplanades used for rallies and spectacles, deliberately emptied of previous social clutter.

This was architecture as control—of movement, of visibility, of collective imagination.

Rationalism, triumphalism, and the sea

Fascist architecture in Bari oscillated between two styles: stripped Neoclassicism and Rationalism. The first sought to evoke imperial Rome through simplified columns, unornamented pediments, and austere symmetry. The second embraced modernist materials and geometries but restrained their expressive potential, emphasizing clarity over invention.

One of the key buildings from this period is the Palazzo della Provincia, completed in the mid-1930s. Towering over the Lungomare, it combines Rationalist purity with symbolic flair: a tall central tower reminiscent of a campanile, flanked by rectangular wings with uniform fenestration. The exterior is severe but elegant, clad in travertine and pierced with monumental doorways. Inside, a vast fresco cycle by Mario Prayer celebrates Apulian agriculture, labor, and fascist unity—figures posed in neoclassical grandeur, devoid of individual expression but rich in allegory.

Another important site is the Casa del Mutilato, a kind of temple to state-sponsored sacrifice. Designed for veterans of the First World War, the building features geometric volumes, pilaster strips, and interior reliefs of armored soldiers and Roman eagles. It is solemn, cold, reverent—where architecture becomes a substitute for liturgy.

The Fascist palette in Bari favored:

- Travertine and limestone: Echoing ancient Rome and reinforcing a link to territory.

- Bronze and marble reliefs: Used to depict abstract ideals—youth, work, unity—over historical specificity.

- Vertical emphasis: Suggesting both ascension and surveillance.

The regime’s fascination with the sea also played a role. Bari, situated on the Adriatic, was projected as a launching point for Italy’s “return” to the East. Architectural language followed suit: buildings opened toward the water, framed it, used it as backdrop for their solemnity. The Lungomare became a corridor of ideology.

But this language, for all its visual control, never fully displaced the city’s older topographies. Bari Vecchia remained stubbornly alive, its narrow alleys immune to grid logic. The older churches, even when dwarfed by Fascist façades, retained their devotional pull. The regime could build over, but not entirely erase.

Art exhibitions and cultural consolidation under the Duce

In tandem with its architectural program, the Fascist regime sought to consolidate visual culture. Art exhibitions became tools of ideological education. In Bari, this meant the establishment of provincial salons that celebrated Apulian artists who embraced “healthy” themes: rural labor, family, religious piety, or historical grandeur. Modernist experimentation was tolerated only insofar as it served the state.

The Fiera del Levante became not just a trade fair, but a cultural platform. Within its pavilions, art exhibitions juxtaposed local craftsmanship with idealized depictions of fascist virtue. Sculptures of muscular farmers, paintings of orderly harvests, and architectural models of planned towns were presented as proofs of the regime’s civilizing mission.

At the same time, education and propaganda merged in visual form. Schools incorporated drawing into their curricula as a civic duty. Public murals—though rare in Bari compared to Rome or Milan—occasionally appeared in schools and post offices, depicting scenes of progress and harmony. The human body, especially the male form, was idealized in ways that echoed both ancient statuary and contemporary militarism.

Yet cracks in this visual orthodoxy emerged even before the regime’s collapse. Some artists—trained in Naples or Rome—began to explore more nuanced forms. A few works introduced ambiguity, softness, even irony into the otherwise rigid canon. These were not overt acts of resistance, but gestures of distance. The space between monument and man began, subtly, to reopen.

By the end of the 1930s, Fascist Bari was both a real city and a mirage: its boulevards wide, its buildings symmetrical, its symbols aligned—but its past unconquered, its people unhomogenized. The art of this era did not survive by inspiration but by command. And yet it endures, not as propaganda, but as evidence—of an ideology that built in stone what it could not quite stabilize in society.

Today, the Fascist buildings of Bari stand mute, often reoccupied by democratic institutions or transformed into galleries and schools. Their pediments are weathered. Their inscriptions fade. And in their silence lies a caution: that power expressed in perfect geometry cannot always anticipate the unruly human lines that follow.

Postwar Reconstruction and Contemporary Experimentation

When the war ended, Bari awoke to a new kind of ruin. The city had escaped the worst of the Allied bombing that devastated other Italian urban centers, but it bore deep scars—physical, social, and cultural. Fascist buildings loomed unfinished or abandoned. Churches stood empty of congregants. Industry struggled to restart. And perhaps most acutely, the city faced a question that had never been asked so openly: what kind of future could a port city, peripheral to both the national art scene and the postwar industrial boom, imagine for itself?

The decades that followed did not produce a singular artistic movement or a heroic rebuilding campaign. Instead, Bari’s postwar art history is a story of improvisation, experimentation, and slow reanimation. Artists, architects, and cultural workers stitched together a new identity for the city from fragments—sometimes working with the inherited vocabulary of the past, sometimes discarding it altogether.

From rubble to regional rebirth

Bari’s early postwar efforts were practical, not utopian. The immediate challenge was housing. Displaced families crowded into makeshift dwellings in and around the old city, and government attention turned to rebuilding infrastructure. Artists played a supporting role in this process—decorating churches, producing commemorative murals, and restoring damaged buildings—but the avant-garde had not yet arrived.

One of the quiet successes of this period was the gradual reactivation of cultural institutions. The Pinacoteca Metropolitana “Corrado Giaquinto”, Bari’s major art gallery, reopened in expanded quarters and began acquiring modern works alongside its collection of Apulian Renaissance and Baroque art. Exhibitions of living painters returned to the public calendar. The Accademia di Belle Arti, formally recognized in the 1970s but building on earlier pedagogical roots, nurtured a generation of postwar artists with new tools, new media, and new questions.

Among the notable figures of this transitional generation was Franco Sumerano, a painter and printmaker who explored abstraction through the lens of southern landscape. His canvases from the 1960s and ’70s—textured with sand, fabric, and pigment—evoke Apulian fields and seascapes not as depictions, but as sensations. His work straddled the line between landscape and material experiment, tradition and departure.

Sumerano’s generation faced a dual constraint:

- A lack of major collectors or state commissions in the south, limiting their financial independence.

- An entrenched cultural hierarchy that treated Rome and Milan as the only serious centers for modern art.

Despite this, Bari’s artists began to cultivate a local modernism—not in grand gestures, but in modest persistence.

Public murals, peripheral galleries, and grassroots studios

By the late 20th century, a new artistic infrastructure emerged in Bari, not imposed from above but developed from below. Independent galleries, cooperative studios, and university-affiliated projects began to reclaim the city as a site of contemporary experimentation. The old binary—Florence for the past, Milan for the future—began to fracture.

One of the most intriguing developments was the rise of public art initiatives in the city’s peripheral neighborhoods. In the working-class quarter of San Paolo, for example, large-scale murals began to appear on the sides of apartment buildings, blending street art with traditional iconography. These were not spontaneous acts of graffiti but commissioned works, often created by collectives in partnership with schools and cultural associations.

A 2013 mural titled San Nicola Pop, painted by the artist collective Fx, reimagines Bari’s patron saint not in medieval robes but in contemporary streetwear, flanked by symbols of migration, labor, and care. The image sparked both admiration and controversy—proof that Bari’s sacred iconography could still ignite civic conversation.

Parallel to these murals, a constellation of small contemporary art spaces flourished:

- Spazio Murat, an exhibition venue in the city center, curated shows that merged visual art with design and performance.

- Casa delle Arti, located near the university, supported emerging artists with residencies and collaborative projects.

- The ARTcore, founded in 2008, offered a hybrid space for exhibitions, workshops, and music—a counter-institution for Bari’s younger generation.

These spaces broke down traditional hierarchies of genre and media. Painters worked alongside video artists. Performers collaborated with sculptors. Theory was not an abstract text but a live conversation.

This grassroots ecology signaled a turning point: Bari was no longer waiting for recognition from Rome or Milan. It was building its own.

Bari’s artists between Rome, Milan, and the Balkans

As Italy’s economy and cultural map globalized in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Bari’s geographic position—once a symbol of marginality—became a new asset. Facing the Adriatic, with historical ties to the Greek and Slavic worlds, the city began to reimagine itself not as southern periphery, but as Mediterranean node. Artists responded accordingly.

A key example is Michele Giangrande, a contemporary Bari-based artist whose installations and conceptual works engage with themes of borders, fragility, and historical sediment. His 2010 project Le Pietre di Bari involved collecting fragments of local architecture—broken balustrades, chipped tiles, rusted hinges—and arranging them in gridlike assemblages that spoke both of ruin and of continuity. It was archaeology as art.

Giangrande, like many of his contemporaries, divides his time between Bari and larger centers. But his work remains tied to the city’s textures: its stone, its scale, its slow temporality.

Other artists turned eastward. Collaborative programs with Albania, Croatia, and Greece emerged, many facilitated by the Fiera del Levante’s evolving role as a cross-Adriatic cultural forum. Exhibitions highlighted shared postwar histories, ecological anxieties, and diasporic memory. Bari, once narrowly Italian in its artistic imagination, was becoming plural.

Three tendencies have come to define Bari’s contemporary art scene:

- A preference for material experimentation—rust, fabric, cement—over polished finish.

- A blurring of public and private, sacred and profane, in both imagery and venue.

- A persistent engagement with history—not as nostalgia, but as tension, palimpsest, and provocation.

What emerged from Bari’s postwar decades was not a dominant style but a mode of survival: art as reparation, improvisation, and quiet audacity. There were no manifestos, no grand breakthroughs, no biennial triumphs. But there was—and remains—a deep seriousness, shaped by the city’s layered past and its restless geography.

Bari’s artists today walk through a city haunted by its own stone—Norman arches, Byzantine crypts, Fascist colonnades—and still find ways to respond, not with rejection or mimicry, but with something else entirely: a practice that listens, adapts, and endures.

Biennials, Borders, and the Adriatic Renaissance