Galway has long thrived on its margins. Perched on the western edge of Ireland where the River Corrib meets the Atlantic, it is a city shaped by tides—both literal and cultural. While smaller than Dublin or Cork, Galway has historically punched above its weight in artistic influence, thanks in large part to its role as a crossroads: between Gaelic and Anglo-Norman traditions, between the European continent and the Irish interior, between the old and the new. Its art history is therefore one of confluence—a tapestry woven from local craft, maritime trade, religious devotion, theatrical innovation, and, increasingly, cosmopolitan experimentation.

From its earliest foundations in the 12th century as a Norman trading post, Galway’s identity was bound up with connectivity. The city’s so-called “Tribes”—the 14 merchant families who governed it from the medieval period into the 19th century—were instrumental in cultivating this outward-facing ethos. Trade with Spain, France, and Portugal brought not just wine and cloth but also iconographic styles, pigments, and decorative motifs. A crucifix carved in local stone might sit within a church whose stained glass bore the influence of French Gothic or Spanish Marian iconography. Galway, in effect, was never a purely insular town. Even in the centuries of colonial suppression and economic hardship that followed, this liminal quality remained part of its cultural DNA.

Unlike cities whose artistic prestige was anchored in royal academies or aristocratic patronage, Galway’s creative energy has historically been bottom-up. Its arts scene grew from the churches, the streets, the markets, and later, the theatres and pubs. Even today, Galway’s visual culture remains deeply entwined with performance, music, and storytelling. This is a place where art often speaks with an accent—sung, enacted, or scrawled in chalk on a sidewalk. It is the only Irish city where the Irish language is still widely spoken and sung in everyday life, influencing the rhythm and imagery of artistic production. The proximity to Gaeltacht regions like Connemara ensures a continuous exchange between rural folklore and urban artistry.

In more recent decades, Galway has become known internationally for its vibrant festival culture and high density of working artists. The Galway International Arts Festival, begun in 1978, has grown into one of Europe’s premier multidisciplinary celebrations of creativity. And when Galway was designated European Capital of Culture in 2020—a fraught but ambitious endeavor—it signaled not just recognition of the city’s artistic legacy, but also its forward-facing vision. Art in Galway is not museum-bound; it spills onto the streets, into old warehouses and repurposed churches, across the wild landscapes of the west.

To understand Galway’s art history is thus to appreciate the idea of porosity: between land and sea, tradition and experimentation, image and story. It is a city where art is not only made but lived—a vibrant, sometimes chaotic interplay of old symbols and new forms. The chapters that follow will trace that history from its stone-carved beginnings to the digital, interdisciplinary networks of today.

Medieval Galway – Religious Patronage and Civic Identity

To enter medieval Galway is to enter a fortified city of stone, ringed by walls and crowned with steeples. In the late Middle Ages, Galway was less a city in the modern sense than a walled mercantile town, where religion and commerce flowed in tandem, and where art functioned primarily to serve spiritual, civic, and familial honor. Art in this era did not hang on walls as objects of aesthetic admiration—it was integrated into architecture, ritual, and the visual language of public and private life.

Religious art dominated the visual culture of medieval Galway. From the 13th century onwards, the city’s churches became the primary patrons of painting, sculpture, and decorative craft. Chief among these was the Collegiate Church of St. Nicholas, founded in 1320 and still standing today as a testament to Galway’s medieval religiosity. The church, dedicated to the patron saint of sailors—a fitting choice for a maritime hub—was adorned with stone carvings that blended Norman and Gaelic motifs: angular arches, stylized foliage, grotesques, and heraldic shields. These carvings were not purely decorative; they encoded familial allegiance and spiritual narratives into the very bones of the city.

The stone masons of Galway were both artisans and storytellers. Their carvings on tombs, doorways, and baptismal fonts displayed a visual literacy that drew on both local folklore and ecclesiastical iconography. One can still find medieval effigies—some near life-size—of knights and civic leaders, depicted in high relief, hands clasped in prayer, swords resting at their sides. These stone figures served both devotional and propagandistic purposes, ensuring the memory and status of their patrons within the sacred space of the church.

Galway’s famed “Tribes”—the 14 merchant families of Anglo-Norman origin who dominated the city’s politics and economy—also left their mark through heraldic art. Their coats of arms were carved above doorways and on civic buildings, proudly declaring their lineage and control. This heraldry functioned as a kind of public branding system, where visual symbols replaced words for an audience that was, more often than not, illiterate. The Lynch Memorial Window, often cited as the oldest example of civic commemoration in Ireland, encapsulates this blend of religious and familial iconography. It is said to mark the site where Mayor James Lynch FitzStephen hanged his own son for murder—a dramatic tale likely embellished over centuries, but one that reveals how civic virtue and visual storytelling intertwined.

The art of manuscript illumination, while more commonly associated with the great monastic centers of the east and north, also made its way into Galway’s orbit. Religious texts with intricate calligraphy and marginalia may not have been produced in the city itself but were certainly imported, read, and revered. Artifacts from this period occasionally surface in collections and auctions, bearing the hallmarks of Western Irish stylistic peculiarities: curvilinear motifs, zoomorphic initials, and interlacing knotwork.

We must also consider the subtle influence of Galway’s international connections on its medieval art. As a trading port linked to the Iberian Peninsula and France, Galway absorbed artistic influences via ecclesiastical channels and merchant exchanges. Spanish religious iconography, in particular, found its way into Galway’s devotional art, likely through imported altarpieces or illustrated devotional books. The Gothic architectural style, so prominent in mainland Europe, seeped into Galway’s ecclesiastical structures, though always adapted to local stone and conditions.

One overlooked but fascinating area of medieval Galway’s art history is funerary culture. Gravestones from this period, now eroded by salt air and centuries of rain, show a visual evolution from crude crosses to more ornate depictions of souls in purgatory, angels bearing trumpets, and Latin inscriptions. These carvings reflect not just artistic skill but theological shifts—particularly the medieval preoccupation with salvation, judgment, and the afterlife.

By the end of the 15th century, Galway’s art scene had begun to solidify around the symbols of power and piety. Artistic production was primarily anonymous—signed works were rare, as artists were considered craftsmen rather than individual geniuses. Yet their legacy endures in the carved limestone, stained glass, and architectural harmony that still define Galway’s medieval core.

In short, the art of medieval Galway was not passive decoration. It was an active tool of devotion, governance, and identity-making—a visual script through which a small, walled city proclaimed its faith, its power, and its place in a broader world.

Early Modern Period – Trade, Portraiture, and Heraldic Art

The early modern period in Galway was an era of shifting allegiances and visual refinement. From the late 16th through the 17th century, the city underwent major political, economic, and cultural transformations. These changes found expression in its art—not in grand frescoes or royal commissions, as might be found in Italy or France, but in subtle yet sophisticated forms: family portraits, heraldic carvings, civic embellishments, and increasingly personal decorative arts. The artistic output of this time reflects a community grappling with its identity in a world becoming both more connected and more unstable.

Galway’s geographic position once again played a defining role. As a port city trading with Spain, Portugal, and the Low Countries, it enjoyed access to materials and visual trends far beyond the norm for a town of its size. Imported pigments, textiles, and even artists passed through the quays, and this exchange left its mark on the city’s art. It was during this period that we begin to see portraiture emerge—not necessarily on the grand scale seen in European courts, but through painted likenesses and stylized renderings of prominent merchant figures, often commissioned for family chapels or council halls.

While few examples of early Galway portraiture survive intact, written records and fragments suggest that the Tribes of Galway began to use art to assert their lineage and social standing in increasingly visual ways. A painted likeness of Mayor Dominick Lynch or a woodcut depiction of James Blake wasn’t simply about vanity—it was about continuity, legitimacy, and an assertion of local power in the face of colonial pressure from English authorities. These images may have been produced by itinerant artists traveling from Dublin or even London, brought in for specific commissions and then lost to history.

Alongside portraiture, heraldic art flourished. As English control of Ireland intensified under Tudor and later Stuart rule, Galway’s merchant class found itself caught between Gaelic traditions and the expanding bureaucracy of English heraldry. Coats of arms, once carved casually above doorways or painted onto wooden panels, now took on new importance. They were submitted to the Office of the Chief Herald, codified according to the rules of English gentry, and displayed with more rigid formalism. Yet local variations persisted: hybrid designs combining Gaelic and Norman symbols, iconography referencing seafaring or Christian martyrdom, and Latin mottos that blended religious devotion with mercantile pride.

One remarkable artifact from this period is the Blake Family Memorial, which includes both sculptural and painted elements, reflecting a transitional moment in Galway’s art. The inclusion of religious symbolism, family crests, and architectural elements into a single composition suggests that Galway’s artists—while often anonymous—were capable of working across mediums with a fluency born from necessity and experimentation.

The broader religious context of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation also had profound effects on visual culture. As Galway remained predominantly Catholic in a Protestant-controlled kingdom, its art became a medium of coded resistance. Religious imagery—particularly Marian symbols, saints associated with martyrdom, and images of Christ’s suffering—was used to signal loyalty to the old faith. Domestic devotional objects, often smuggled in or produced in secret, gained aesthetic as well as spiritual importance. Painted crucifixes, hand-colored prints, and rosary beads carved with local motifs provided comfort and identity to a besieged population.

At the civic level, Galway continued to invest in its public image through architecture and embellishment. The 17th century saw expansions of civic buildings, often decorated with carved plaques and stone emblems bearing dates, Latin inscriptions, and images of municipal authority. These were not just records—they were artistic acts of civic self-definition, meant to assert autonomy even as the town’s legal powers diminished under colonial governance.

It is also during this period that we see the emergence of decorative arts and craftsmanship that blur the line between function and fine art. Woodwork in homes, elaborately tooled leatherwork, and embroidered ecclesiastical garments all point to a community invested in the tactile and the visual. The surviving pieces suggest a synthesis of European style and local adaptation, particularly in motifs drawn from Irish flora and fauna.

While early modern Galway never developed a formal art academy or school, its artisans were highly skilled, and its cultural output was rich. The art of this period was not meant to be merely admired—it was meant to speak: of lineage, of resistance, of civic virtue. In a city increasingly under pressure from English centralization and religious persecution, visual culture became both shield and sword.

This period planted the seeds for later developments: the valuing of visual self-expression, the blending of international and local styles, and the assertion of identity through image. Galway’s early modern art was not ostentatious, but it was layered with meaning—its brushstrokes and carvings echoing the complexity of a city negotiating its place in an ever-changing world.

18th and 19th Century Galway – Art in Decline or Transformation?

To the casual eye, 18th and 19th century Galway may appear as a cultural backwater—an era of artistic dormancy amid political disenfranchisement and economic decline. The medieval grandeur had faded, the influence of the merchant Tribes had eroded, and the city, once a node of European maritime trade, was now caught in the tightening grip of British colonial administration. The arts, too, seemed to shrink from public life, their grandeur replaced by a quieter, more domestic presence. But to view this period as an artistic vacuum is to overlook the adaptive power of cultural expression in times of hardship. Galway’s art didn’t disappear—it retreated, reconfigured, and emerged in forms often dismissed by official histories.

At the heart of this transformation was the ruralization of art. As Galway’s urban economy contracted and political power shifted to Dublin and London, many forms of artistic production took root in the countryside. Folk art flourished—unofficial, unsigned, passed hand to hand rather than displayed on salon walls. Painted religious plaques, embroidered altar cloths, carved walking sticks, and storytelling panels were produced by anonymous craftspeople, often for liturgical or communal use. These works were rarely preserved in museums, but they carried deep cultural significance and aesthetic care.

One of the most visible expressions of vernacular art during this period was the growth of devotional imagery in private homes. With the decline of grand religious commissions and the suppression of Catholic practice under Penal Laws, Irish households began producing and acquiring small religious artifacts for personal use. In Galway and its hinterlands, this included painted plaster statues of the Virgin Mary, hand-embroidered prayer samplers, and even framed holy cards. These objects—often tucked into hearth corners or kitchen altars—acted as both spiritual anchors and artistic expressions, decorated with ribbons, shells, or found materials.

Church art, meanwhile, adapted to new realities. As restrictions on Catholic worship loosened toward the end of the 18th century, churches began to reassert their visual presence—albeit on modest scales. In Galway, some chapels and reestablished churches incorporated stained glass and statuary, often sourced from continental Europe. These imports, while not produced locally, were absorbed into the region’s aesthetic and inspired local interpretations. The presence of German or French devotional prints in a Galway parish could prompt local artisans to emulate them in painted form or adapt their compositions for woodcarving.

It is also during this period that the oral and visual arts became deeply intertwined. Galway’s famed storytelling culture, especially in the Irish-speaking west, was accompanied by visual cues: storyboards drawn in ash on hearthstones, illustrations carved into walking sticks or fireplace mantels, and images scratched into slate. These visual forms were ephemeral by design, destroyed with each retelling, but they speak to a culture that never truly stopped making images.

Another key development was the arrival of itinerant artists—traveling portraitists, silhouette cutters, and sign painters who made their living moving from town to town. While rarely considered “fine artists” in the academy sense, these individuals played a crucial role in maintaining visual literacy and image-making skills. In towns like Galway, they offered likenesses to families who could not afford oil paintings, often producing ink or watercolor miniatures framed in simple wood. These portraits are among the earliest secular visual records of Galway’s 19th-century citizens.

Landscape art also began to enter the cultural consciousness of the west during this time, but not initially from within. British artists, often influenced by the Romantic movement, came to Connemara and the Galway coast seeking wildness, ruins, and storm-tossed beauty. Their works—sketches, watercolors, and oil paintings—portrayed the region with a mix of awe and melancholy, often through a colonial lens. While these artists were outsiders, their interest in Galway’s terrain would later inspire local artists to view their own land as a subject worthy of art.

Galway also benefited, albeit indirectly, from Ireland’s growing network of drawing schools and print culture. Even if Galway lacked a formal academy, the spread of illustrated newspapers, printed books, and religious tracts brought new images and ideas into local homes. Lithographs of European paintings, engravings of biblical scenes, and technical drawing manuals allowed Galway’s artists and artisans to learn vicariously, building a vernacular tradition informed by international art.

By the late 19th century, as Ireland edged toward political agitation and cultural revival, seeds were being sown for Galway’s reemergence as an artistic center. The Irish language revival, spearheaded in part by scholars and artists with roots in the west, placed Galway once again in the national imagination. The landscape, the folklore, and the expressive potential of the west began to attract not just tourists but thinkers, poets, and image-makers.

So, was the 18th and 19th century a period of artistic decline in Galway? Only if one equates art solely with oil paintings and marble statues. Viewed more broadly, it was a period of quiet persistence, where art survived in peat smoke, textile threads, and the whispered stories of rural communities. It was a time when image-making was not a profession but a practice—woven into everyday life, resilient in the face of loss, and waiting, patiently, for the next revival.

The Gaelic Revival and Early 20th Century Movements

At the dawn of the 20th century, a cultural fire was kindling across Ireland, and nowhere did it burn more evocatively than in the west. The Gaelic Revival, a movement aimed at restoring Irish language, folklore, and national identity, brought renewed focus to Galway—a region still rich in oral tradition, landscape symbolism, and native expression. While often thought of as a literary or linguistic renaissance, the Revival also had a profound effect on visual culture. In Galway, art became a medium through which ancient identity could be reimagined for modern times.

The backdrop to this period is one of political unrest and idealism. Ireland, long subjugated under British rule, was undergoing a tectonic cultural shift. Organizations like the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), founded in 1893, championed the Irish language and promoted traditional arts as a way to resist Anglicization. Galway—uniquely situated as a bilingual city with direct ties to the surrounding Gaeltacht—played a key role in this effort. Artists, scholars, and nationalists alike turned westward, seeing in Galway a kind of living museum of Irishness, preserved through hardship and relative isolation.

Visual art in this era was profoundly shaped by this idealization. Painters and illustrators, often affiliated with nationalist circles, traveled to Galway and its environs to document “authentic” Irish life. The influence of the Celtic Revival, led by figures such as W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, and George Russell (Æ), reached Galway through both direct engagement and ideological osmosis. While many of these figures were based in Dublin or the east, their artistic gaze was fixed westward. Their aesthetic—rooted in pre-Christian symbols, Celtic knotwork, and mythic imagery—found fertile ground in Galway’s cultural memory.

Illustrative arts flourished in this context. Artists like Beatrice Elvery, though Dublin-based, often portrayed western Irish women in traditional dress, set against windswept landscapes that bore the mark of Galway and Connemara. These images—half romantic, half documentary—became iconic symbols of Irish nationhood, replicated in posters, stamps, and murals. The Aran Islands, just off Galway’s coast, became a particularly potent symbol in visual and literary works alike, thanks to their perceived purity and isolation from colonial influence.

Within Galway itself, local artisans and craftspeople began to engage with these broader trends. Traditional textile arts—particularly weaving, lace-making, and embroidery—were reframed as expressions of national pride. The Congested Districts Board, established in 1891, supported craft education in the west, including in Galway. While primarily economic in intent, these efforts fostered a new appreciation for the decorative arts as a form of cultural preservation. Celtic motifs found their way into hand-stitched garments, altar cloths, and even signage.

One of the most significant institutional developments of the early 20th century was the founding of An Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe in 1928—the national Irish-language theatre, based in Galway. While its primary medium was performance, the visual implications were considerable. Set design, costume, and promotional posters all drew upon Revivalist aesthetics. The theatre became a crucible where language, myth, and imagery converged. Its existence also anchored Galway as a serious cultural player, ensuring that visual artists in the region were increasingly integrated into national movements.

The art produced during this time was rarely abstract or avant-garde. It was representational, symbolic, and often nationalistic—aimed at affirming an Irish identity distinct from that imposed by Britain. Yet, this art also carried contradictions. The romanticization of the west often glossed over the hardships of rural life. Many of the most widely circulated images of Galway—stoic women in shawls, men harvesting peat, barefoot children by stone walls—were painted or photographed by outsiders. This tension between self-representation and external gaze remains a defining issue in the study of Galway’s Revival-era art.

Still, for Galway’s local artists and cultural custodians, this was a period of extraordinary validation. The Irish language was not merely a tool of communication—it became a source of visual inspiration. Lettering styles drawn from ogham and medieval manuscripts began to reappear in signage and typography. Symbols once confined to ancient crosses or jewelry—triskeles, spirals, animal motifs—were repurposed for modern printmaking and design.

This visual turn toward Irishness also impacted education. Art became a tool of instruction in newly established Irish-language schools. Students were taught not just to draw, but to see the world through a Gaelic lens: to sketch the contours of the landscape, to illustrate folktales, to integrate myth into modern identity. These practices laid the groundwork for the later emergence of more formal art education in Galway.

By the 1930s and 1940s, Galway had firmly established itself as both a symbol and site of Irish cultural resilience. While not yet a hub for galleries or modernist experimentation, it had become a generator of visual heritage—embodied in crafts, performance, printed ephemera, and the lingering iconography of nationalism. The seeds planted during the Revival would blossom in the decades to follow, as Galway’s artists moved beyond idealism and into self-invention.

The Theatre of Galway – The Visual Stage

If Galway has a soul, it speaks in performance. From the Gaelic storytelling traditions of the Gaeltacht to the internationally acclaimed productions of the 20th and 21st centuries, the theatre in Galway has always been more than entertainment—it’s a deeply visual, communal act of cultural expression. And while the focus is often on the spoken word, the visual dimension of theatre—its sets, costumes, stagecraft, and promotional imagery—has played an equally crucial role in shaping the city’s artistic legacy.

Theatre in Galway did not begin with modern institutions; its roots stretch deep into folk drama, seasonal rituals, and itinerant performers. Mumming and pageantry—informal, often subversive performances staged in town squares or private homes—were vibrant forms of folk art through the 18th and 19th centuries. These performances, largely visual and physical in nature, used costume and simple props to convey archetypal characters, moral lessons, or comic reversals. They blurred the line between theatre and visual culture, between mask and painting.

The formalization of theatre in Galway took a decisive turn in 1928 with the founding of An Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe, Ireland’s national Irish-language theatre. Located in the heart of the city, An Taibhdhearc was more than a performance venue—it was a bold cultural statement. In an era when the Irish Free State was still finding its voice, this theatre became a platform for reimagining Irishness through Gaelic drama, but also through visual motifs inspired by Celtic Revival aesthetics.

The design ethos of An Taibhdhearc reflected this ambition. Sets were often minimalist, drawn from the earthy textures and austere lines of western Ireland’s architecture and landscape. Costumes incorporated traditional weaves, Aran patterns, and folkloric symbols. Stage lighting was used to evoke the shifting weather of Connemara—mist, dusk, firelight—rendering the theatre an extension of the land itself. Visual artists collaborated closely with directors to produce an immersive aesthetic that was as tactile as it was poetic.

Posters, playbills, and promotional material from An Taibhdhearc also formed an important strand of Galway’s visual art. Lettering styles were drawn from medieval Irish manuscripts; borders recalled Celtic knotwork; colors were deliberately limited and evocative—earth tones, blood reds, and oceanic blues. These designs were often produced by anonymous in-house illustrators or local printmakers, but their aesthetic impact was lasting. They gave Galway’s theatre a graphic identity that echoed the national struggle for cultural authenticity.

The late 20th century saw Galway’s theatrical visual culture expand dramatically with the founding of the Druid Theatre Company in 1975. Founded by Garry Hynes, Mick Lally, and Marie Mullen, Druid brought a new level of artistic ambition and professionalization to Galway’s performing arts. While best known for its groundbreaking productions—particularly of playwrights like John Millington Synge, Tom Murphy, and Martin McDonagh—Druid also transformed the visual expectations of the stage.

Unlike An Taibhdhearc’s Revivalist minimalism, Druid’s aesthetic drew more from European realism and contemporary Irish life. Set designs became psychological landscapes—claustrophobic kitchens, decaying pubs, wind-rattled cottages rendered in exquisite detail. Collaborations with visual artists, sculptors, and lighting designers created theatrical worlds that were as painterly as they were dramatic. Costumes were selected with a curator’s eye for texture and historicity, turning each play into a kind of living tableau.

The company’s international touring also brought Galway’s visual language to global stages. Sets designed in workshops along the Corrib found themselves rebuilt in New York, London, and Sydney, each one carrying the DNA of the west of Ireland in every plank and prop. Druid’s visual success proved that Galway, long seen as peripheral, could define its own modern aesthetic—rugged, haunted, emotionally raw—and export it with power.

Parallel to these formal theatres, Galway’s street performance culture flourished. The Galway Arts Festival (later the Galway International Arts Festival), launched in 1978, became a hotbed for visual experimentation in performance. Giant puppets, mobile installations, performance art, and interactive street theatre turned the city itself into a stage. Artists like Macnas—founded in 1986—revolutionized Galway’s visual theatre with parades and street performances that fused sculpture, costume, and choreography. Their towering puppets and surreal floats, built in studios with paper, wire, and wood, became visual icons of Galway’s postmodern identity: playful, grotesque, majestic.

In this way, Macnas blurred the boundaries between theatre, sculpture, and public art. Their process-based approach—weeks of community-led construction followed by moments of explosive performance—embodied a distinctly Galway ethos: collaborative, chaotic, celebratory. They influenced generations of local artists, many of whom trained as set designers, puppeteers, or costume makers before moving into fine art, film, or installation.

Visual theatre in Galway thus cannot be separated from the city’s broader artistic identity. It is not simply about background decor—it is a language unto itself. Whether in the shadowed lighting of a Druid kitchen, the stylized iconography of An Taibhdhearc, or the kaleidoscopic processions of Macnas, Galway’s theatrical stage is where art becomes atmosphere, where design becomes story.

As we move into the contemporary period, we will see how these visual traditions evolved further, influencing everything from street murals to festival installations and art-school curricula. But the roots of Galway’s visual theatre—steeped in history, place, and a passion for mythic resonance—remain as vital as ever.

The Establishment of Institutions – Galway Arts Festival and GMIT

In the history of art, infrastructure matters. For centuries, Galway’s artists had operated without the benefit of galleries, academies, or major institutions. They worked in homes, parishes, theatres, and streets—often informally, often unseen. But the late 20th century marked a decisive shift. With the founding of the Galway Arts Festival in 1978 and the growth of Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology (GMIT)’s art and design programs in the decades that followed, the city began to acquire the formal scaffolding needed to support a thriving visual arts ecosystem.

The Galway Arts Festival—now the Galway International Arts Festival (GIAF)—was originally a small, community-led celebration founded by a coalition of local enthusiasts, including members of the theatre scene, musicians, and volunteers. Its founding ethos was democratic and expansive: to create a platform for all forms of artistic expression, not limited by discipline or hierarchy. While theatre and music initially dominated its programming, visual art quickly became a cornerstone.

From its earliest iterations, the festival made space for exhibitions of painting, sculpture, and installation art, often held in unconventional venues: old churches, school halls, derelict buildings, and eventually, purpose-built galleries. This openness to site-specific and experimental work allowed artists to engage directly with Galway’s urban and natural landscape, transforming the city into a canvas. Crucially, the festival attracted audiences from outside the traditional art world—tourists, locals, and first-time gallery-goers mingled freely, drawn by the energy of the event.

By the 1990s, as the festival matured, it began commissioning new works and hosting international artists alongside emerging Irish talent. This elevated Galway’s reputation as a cultural hub and encouraged cross-disciplinary experimentation. Visual artists collaborated with choreographers, musicians, and dramatists; installations were paired with soundscapes; video art was projected on castle walls. The result was a deeply hybrid visual culture that resisted categorization and reflected Galway’s boundary-crossing spirit.

At the same time, the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology (GMIT) began to emerge as a significant center for art education. Originally a technical institute, GMIT evolved to include a dedicated School of Design and Creative Arts, based at its Cluain Mhuire campus in Galway City. The art program, formally recognized in the 1980s and expanded in the 1990s, provided structured training in painting, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, and later, digital media and interdisciplinary practice.

GMIT’s art school was not a clone of Dublin’s National College of Art and Design (NCAD). It developed with a distinctive ethos—one deeply influenced by place. Students were encouraged to draw inspiration from the landscape, the language, and the social history of the west. Fieldwork in Connemara, collaborations with local craftspeople, and studio visits with community-based artists were central to its pedagogy. The school fostered an experimental mindset, while maintaining a strong grounding in material techniques.

Over the years, GMIT faculty included a number of respected practicing artists who helped bridge the gap between education and professional practice. Their mentorship encouraged many students to stay in Galway after graduation, contributing to a local arts ecology that was both grassroots and globally informed.

The interaction between GMIT and the Galway Arts Festival was particularly fruitful. Students exhibited work during the festival, volunteered as assistants for major installations, and participated in fringe events. This synergy meant that emerging artists had both a platform to show their work and access to critical discourse through talks, workshops, and feedback sessions. It also helped establish Galway as a place where artistic careers could begin and be sustained—a significant shift from earlier decades, when talent often migrated east to Dublin or abroad.

During this same period, Galway saw the rise of important galleries and artist-run spaces, many of them born out of the festival and school ecosystems. The 126 Artist-Run Gallery, founded in 2005, is one such example—an independent, not-for-profit space that provides emerging and mid-career artists with a venue to show experimental work. Like others that sprang up in the 2000s, it reflects the DIY ethos of Galway’s art community: flexible, collaborative, and committed to risk-taking.

In the background of all this institutional development, Galway City Council and local organizations began investing in public art commissions and artist residencies. Arts officers worked to integrate visual art into urban planning, often commissioning murals, sculptures, and temporary installations in parks and civic spaces. These efforts helped embed art into the everyday life of the city—not as an elite pursuit, but as something encountered while walking to the shop or sitting by the docks.

The cumulative effect of these institutions—GIAF, GMIT, artist-run spaces, and public initiatives—has been transformative. Galway, once marginal in terms of visual art infrastructure, became a city where creative ambition could be realized. It created a pipeline from education to exhibition, from studio to street, and from local identity to international conversation.

Today, many of Ireland’s most compelling contemporary artists either trained in Galway, exhibited their early work during the festival, or maintain studios in the city. And while challenges remain—funding, housing, and space being constant concerns—the foundation laid by these institutions continues to sustain Galway’s artistic vibrancy.

Street Art and Folk Expression – The Living City

Galway’s streets hum with color, language, and life. Walk down Quay Street or meander through the West End, and you’ll encounter a city in perpetual conversation with itself—on its walls, in its windows, across lampposts, bins, benches, and shopfronts. Galway’s street art and folk expressions form a kind of visual undercurrent: ephemeral, populist, and fiercely local. While rarely preserved in museums or sold at auction, this living art is essential to understanding the city’s identity—a blend of resistance, humor, memory, and pride.

Street art in Galway is not a new phenomenon. While spray-painted murals and graffiti tags are often associated with the late 20th century, Galway’s tradition of visual expression in public space has older roots. Shop signs hand-painted in Irish, pub façades decorated with Celtic motifs, and chalk drawings scrawled during festivals all speak to a historical desire to make art accessible and participatory. In a city with strong oral and musical traditions, it’s natural that its visual culture would also find a home outdoors, among the people.

The rise of contemporary street art in Galway can be traced to the 1980s and 1990s, as a generation of young artists, inspired by global graffiti culture and local activism, began to treat the city’s walls as their canvas. Political murals emerged during this time, often commenting on national issues—housing, the Irish language, environmental threats—as well as local struggles. These murals were typically created without formal approval, and many have since vanished under coats of paint or gentrification. But they helped establish Galway’s reputation as a city of visual resistance, where art could speak truth to power in bold, public ways.

A particularly rich site of Galway street art has long been the Fishmarket area near Spanish Arch, where abandoned buildings and industrial walls became unofficial galleries. In the early 2000s, the city began to tolerate, and occasionally even commission, murals in this zone, leading to collaborations between street artists and local youth groups. These murals became palimpsests—layered with new imagery, tagged over, restored, then transformed again. Their impermanence is part of their power: they reflect a city in motion.

Language plays a central role in Galway’s street art. Unlike Dublin or Belfast, where English dominates most public signage, Galway’s bilingual culture often manifests visually. Slogans, stencils, and poetry snippets appear in both Irish and English, sometimes interwoven within the same piece. This use of Gaeilge is not ornamental—it’s a cultural assertion, a way of localizing global styles and reminding passersby of Galway’s linguistic identity.

In recent years, artists like Finbar247, Signs of Power, and others have gained recognition for their contributions to Galway’s visual streetscape. Their works range from large-scale figurative murals to typographic pieces that play with old Irish script and contemporary graphic design. These artists often reference local folklore, portraits of historical figures, or abstract representations of community struggle and resilience. The city council, once hesitant, now occasionally sponsors these works through public art grants and festival partnerships.

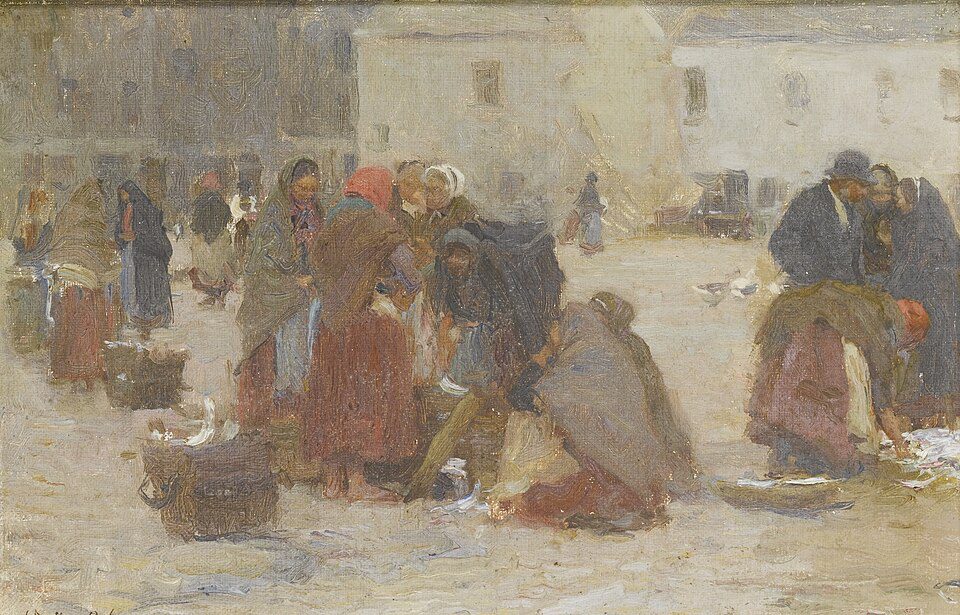

Beyond spray paint and stencil, Galway’s street expression extends into folk craft and market aesthetics. The Galway Market, held near St. Nicholas’ Church, is as much an art exhibition as it is a commercial enterprise. Stalls are adorned with hand-stitched banners, hand-lettered signs, and quirky sculptural flourishes. Vendors sell not only food and produce but also ceramics, jewelry, textiles, and carved wood—each a miniature artwork born of local material and personal tradition.

One cannot discuss Galway’s folk expression without acknowledging the impact of festivals. The Galway International Arts Festival, Macnas parades, and smaller events like Cuirt or the Baboró festival for children often spill into the streets with a riot of temporary installations: lantern sculptures, community-built floats, kinetic artworks, and impromptu exhibitions on hoardings or in alleyways. These moments blur the line between professional and amateur, between artist and audience.

This democratization of visual space is key to Galway’s folk aesthetic. Here, art is not something that hangs behind glass but something that can be pinned to a pole, painted on a bin, or chalked onto cobblestones. It invites dialogue. It changes with the weather, the politics, the crowd. It disappears and reappears. It lives.

Even the weatherworn nature of Galway’s streetscape becomes part of its visual story. Moss-covered stone, rusting signage, salt-bleached wood—all serve as accidental collaborators in the city’s outdoor gallery. The art here is not clean or curated—it’s wild, layered, and often unclaimed. But that’s exactly what makes it so alive.

In a time when many cities are losing their street character to homogenized urban design and corporate branding, Galway remains defiantly textured. Its street art is a living archive—of protest, of celebration, of bilingual wit and handmade care. And as we will see in the coming chapters, this public-facing spirit continues to inspire not just muralists and sign-painters, but also contemporary visual artists working in new media, performance, and installation.

Women Artists of Galway – Visibility and Voice

In the narrative of Galway’s art history—as in so many others—women have often been present but under-credited, central yet marginalized. Their hands shaped altar cloths, their minds built festivals, their voices told stories through paint, thread, and performance. Yet for much of the past, they have appeared only in footnotes: “anonymous,” “assistant,” “wife of.” In recent decades, however, women artists in Galway have stepped into greater visibility, not only as creators but also as curators, educators, and agitators—claiming space in galleries, festivals, and public discourse.

To understand the contributions of women artists in Galway, we must begin by revaluing the traditional and domestic arts, long excluded from formal art histories. For centuries, Galway women produced visual culture through embroidery, lace-making, ceramics, and textile design. These were not simply functional crafts but aesthetic forms passed through generations. Embroidered altar cloths and vestments, often created in convents or women’s collectives, featured intricate patterning and religious iconography rendered with technical brilliance. Yet these objects were rarely signed or displayed outside religious contexts.

In rural Galway, quilt-making, knitting, and weaving were similarly undervalued as “women’s work,” despite their deep ties to local identity and community cohesion. Only in recent decades have scholars and curators begun to reframe these practices as part of Ireland’s visual and material culture, recognizing their narrative and symbolic power.

The mid-20th century saw a shift. As art education expanded, more Galway women began to receive formal training. By the 1970s and 1980s, they were emerging as distinct voices within Ireland’s contemporary art movement, even as institutional support remained limited. Many of these artists used their practice to explore themes of gender, place, memory, and language, often in experimental or interdisciplinary formats.

One key figure from this period is Máirín Duffy, an artist and educator who worked across painting, textile, and print media. Her work, often inspired by the landscapes and lore of Connemara, combined abstraction with feminist introspection. Though her name is not yet widely known outside of Galway, Duffy was instrumental in mentoring younger artists and establishing informal studio spaces in the city during the 1980s and 1990s.

The feminist wave that reshaped Irish theatre, poetry, and literature also touched Galway’s visual arts scene. Artists began forming collectives and cooperatives, often out of necessity. Shared studios became both economic solutions and ideological spaces, where collaborative practices challenged the individualist narratives of traditional art history. These spaces nurtured not just visual innovation but also dialogue about power, representation, and the role of women in cultural production.

The influence of academic institutions, especially GMIT’s art program, cannot be overstated. From the 1990s onward, the school trained a growing cohort of women artists who stayed in Galway to build their careers. Their work often blended fine art with community practice, exploring issues of identity, migration, mental health, and ecology through installation, video, and performance.

One such artist is Ruby Wallis, whose photographic and video works explore intimacy, landscape, and the female gaze. Based in Galway, Wallis’s practice investigates how bodies move through and are shaped by rural spaces, challenging traditional representations of Irish femininity and place. Her work has been exhibited internationally but remains deeply rooted in the western Irish context.

Another key contemporary figure is Jennifer Cunningham, known for her atmospheric prints and drawings that explore memory, architecture, and psychological space. Cunningham’s work often features Galway city itself—its buildings, alleyways, and interiors—rendered as layered, dreamlike environments. As a teacher and mentor, she has helped bridge the gap between the academy and the wider arts community.

The rise of feminist art in Galway has also been accompanied by curatorial activism. Artists and curators alike have worked to ensure that women’s art is not relegated to “special interest” categories but seen as integral to the city’s creative identity. Exhibitions such as ‘In Her Shoes’ and ‘Out of Sight: Women Artists in Ireland’ have spotlighted the work of women historically excluded from major collections. Meanwhile, festivals and independent galleries have increasingly prioritized gender equity in programming.

Public art has provided yet another platform. Artists like Ciara O’Neill, whose work includes both street murals and gallery pieces, bring women’s stories into the urban fabric. Their interventions challenge patriarchal histories by asserting a bold, visible presence in public space.

Yet challenges remain. Access to funding, studio space, and professional networks still reflect broader gender imbalances in the art world. For many women artists in Galway, the labor of art-making is doubled by caregiving responsibilities or precarious employment. But their resilience, and the growing support networks among them, has led to a palpable shift in recent years.

Today, women artists in Galway are not only visible—they are shaping the discourse. They are reclaiming materials and methods once dismissed as decorative or domestic. They are telling new stories, centering the female experience, queering the gaze, and building structures that include rather than exclude. Their legacy is not just aesthetic—it is institutional, pedagogical, and political.

As we continue through the 21st century, Galway’s art history must be rewritten to fully account for these contributions. To do so is not merely a corrective gesture—it is to recognize the fullness of the city’s artistic soul.

The Art of the Landscape – Connemara and the Western Light

There is a light in the west of Ireland that artists return to again and again. It is a light that shifts quickly, silvers the sea one moment and cloaks the bog in mist the next. It is diffuse, melancholy, sometimes fierce. For centuries, this elusive light—and the landscape it reveals—has been central to the visual culture of Galway. The county’s geography is not simply backdrop; it is subject, material, and mood. It is a palette of stone, water, heather, and sky, rendered in brushstrokes, photographs, and lines of graphite. And nowhere is this more powerfully felt than in Connemara, the rugged region that dominates Galway’s western edge.

Connemara’s reputation as a muse for artists has its roots in both reality and mythology. It is often described as “otherworldly,” a term that hints at both its sublime beauty and its historical marginalization. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, painters, poets, and photographers ventured westward seeking a version of Ireland untouched by modernity—what W.B. Yeats famously called “the deep heart’s core.” This romanticism, while occasionally reductive, also helped cement Connemara as one of the most visually significant regions in Irish art.

Early representations of the landscape often came from outsiders, many of them British or continental visitors with Romantic or ethnographic sensibilities. They painted Connemara’s mountains and coastlines in dramatic hues, emphasizing its remoteness and its “primitivism.” Artists such as Paul Henry (although born in Belfast) and Jack B. Yeats brought Connemara to wider audiences in the early 20th century. Paul Henry, in particular, distilled the west into a visual language of soft blues, ochres, and whites—clouds rolling over cottages, lone figures walking through vast, empty fields. His work helped codify an aesthetic still associated with Galway’s west: minimal, contemplative, reverent.

But even as these images circulated internationally, local and regional artists were developing a more intimate, grounded engagement with the land. They knew the changing colors of a single hill at dusk. They understood how fog behaves in valley floors. Their work was not just observational—it was lived. Artists like Sean McSweeney, though more often associated with Sligo, also captured Galway’s bogs and shorelines with abstraction and lyrical intensity. Their brushwork mimicked the textures of peat and granite, rain-lashed fields and lichen-covered stones.

In more recent decades, a younger generation of Galway-based artists has continued this landscape tradition, while also interrogating its assumptions. Where earlier works often portrayed the land as untouched or eternal, contemporary artists address the environment as layered, politicized, and shaped by human histories. Dorothy Cross, though based partly in County Cork, has strong connections to the west of Ireland. Her installations and sculptures often use marine materials—shark skin, boats, sea-worn wood—to explore themes of memory, mortality, and ecological fragility. Her work captures the raw beauty of the west while also asking what it means to inhabit and interpret it in the Anthropocene.

Photography has also become a major medium for engaging with the Galway landscape. Artists such as Ruby Wallis and Tommy Weir use the camera not simply to document but to perform acts of looking. Wallis, in particular, explores how the female body moves through rural space, challenging the disembodied gaze of traditional landscape photography. Her work emphasizes subjectivity, affect, and embodied knowledge.

The material culture of the west—stone walls, turf stacks, rusting farm implements—also informs many visual practices. Some sculptors and mixed-media artists incorporate these materials directly into their work. Others use them symbolically, as metaphors for endurance, erosion, or resistance. In Galway’s landscape art, the boundaries between nature and culture, past and present, are often intentionally blurred.

Art schools and residencies in the region have further fostered this dialogue. Programs such as those at GMIT and Cill Rialaig (though the latter is technically in Kerry, many Galway artists participate) encourage site-specific and landscape-responsive practices. Fieldwork, drawing excursions, and plein air painting remain central to how artists engage with their environment—but these traditions have been expanded to include sound art, performance, and environmental installation.

One notable contemporary example is the Clifden Arts Festival, held annually in the heart of Connemara. The festival showcases not only performances and readings but also visual art exhibitions that respond directly to place. Artists are often invited to create works inspired by or situated within the surrounding landscape, deepening the sense of dialogue between artist and environment.

The spiritual dimension of the land also persists. Many artists speak of Connemara not simply as a place but as a presence—mystical, humbling, even antagonistic. The landscape resists easy depiction. It is too mutable, too weather-bound. Yet this very difficulty inspires formal innovation. Artists experiment with layered materials, scratched surfaces, shifting scales. Their work becomes an analogue to the landscape itself: unstable, luminous, and alive.

Crucially, the western Irish landscape is no longer viewed as separate from social realities. Artists address the effects of rural depopulation, climate change, and land ownership, layering these themes into their visual language. This convergence of the aesthetic and the political is one of the defining features of 21st-century landscape art in Galway.

To engage with Galway’s landscape is to engage with time—deep geological time, cyclical agricultural time, and the intimate time of personal memory. Whether rendered in oil, captured in pixels, or etched into peat, the western light continues to challenge and inspire. It asks not simply to be seen but to be known. And in doing so, it ensures that the landscape remains not just a subject of art, but one of its most vital collaborators.

Contemporary Artists and Collectives

In the 21st century, Galway’s visual art scene has grown into a vibrant, interconnected network—fueled by collectives, studios, festivals, and independent voices who resist easy classification. Today, artists in Galway work across disciplines and media: from sculpture and installation to performance, video, socially engaged practice, and digital art. While rooted in place, their work speaks to global concerns—ecology, migration, identity, language, memory—offering nuanced visions shaped by Galway’s unique cultural atmosphere.

Central to this contemporary flourishing has been the rise of artist collectives and shared studio spaces, which provide not only logistical support but also ideological community. These collectives function as alternatives to the commercial gallery system—horizontal, collaborative, and frequently experimental in their programming. Among the most influential is 126 Artist-Run Gallery, founded in 2005 and still a cornerstone of Galway’s art infrastructure.

126 was born out of a need for artists to control their own means of exhibition and curation. Its founders—many of them recent graduates of GMIT—envisioned a non-commercial, democratic space where emerging artists could test boundaries and exhibit new work without gatekeeping. Over the years, the gallery has showcased everything from politically charged installations to performance art and experimental video. It operates with a rotating committee, emphasizing collective authorship and curatorial diversity, and frequently engages with international artist-run initiatives, keeping Galway in conversation with wider global art trends.

Another key space is Engage Art Studios, a collective studio housed in the historic Cathedral Building near Eyre Square. Established in 2004, Engage provides affordable workspace for over a dozen artists and runs regular open studios and exhibitions. It has become a critical anchor for Galway’s working artists—offering not just physical space, but a culture of mutual support, skill-sharing, and public engagement.

Galway’s contemporary artists are united less by style than by an ethos of experimentation and responsiveness. Their practices often emerge from and return to the city’s specific textures: its coastlines and boglands, its layered languages, its changing demographics. Artists like Ann Maria Healy, Laura O’Connor, and Cecilia Danell represent a new wave of Galway-based creators whose work is conceptually rigorous while remaining emotionally and visually resonant.

Cecilia Danell, for example, is known for her richly atmospheric paintings that explore solitude, memory, and the psychology of landscape. Originally from Sweden but long based in Galway, Danell’s work reflects both the familiarity and strangeness of the Irish terrain. Her studio process often begins with walking—tracing paths through Connemara or the Burren—and then translating those experiences into oil on canvas. Her compositions evoke dreamlike, empty spaces that resist narrative closure, emphasizing perception over representation.

Laura O’Connor works primarily in installation and video, often incorporating elements of performance and ritual. Her work explores the intersections of gender, embodiment, and historical memory, sometimes drawing on Catholic iconography and childhood folklore. O’Connor’s installations are immersive and sensorial, often involving fabric, scent, and ambient sound, creating a space where the viewer becomes participant.

Collectives such as Interface, a residency and project space located in the Inagh Valley in Connemara, offer rural counterpoints to the urban studios of Galway city. Interface hosts artists from Ireland and abroad, providing them with the chance to respond directly to the landscape through research, fieldwork, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The result is a growing body of site-specific and eco-critical work that challenges traditional divisions between art and science, nature and culture.

Galway’s contemporary artists are also deeply engaged with social and political issues, particularly in the realm of migration, housing, and environmental justice. Many are involved in community-based art projects, partnering with NGOs, schools, and marginalized groups. These projects are not simply outreach—they are integral to how art is conceived and produced in Galway today. The city’s history of grassroots activism and its tradition of public expression (through theatre, street art, and protest) have created fertile ground for socially engaged practice.

Another major shift in recent years has been the embrace of digital and hybrid forms. Artists working with video, VR, sound, and online platforms are reshaping how Galway’s art is distributed and experienced. The COVID-19 pandemic, while deeply disruptive, accelerated this trend, leading to a surge in virtual exhibitions, augmented reality art walks, and remote residencies. Platforms like G126’s digital archive and Interface’s online artist talks helped sustain community and visibility during periods of lockdown and isolation.

Festivals continue to play a key role in amplifying contemporary visual art. The Galway International Arts Festival, along with more targeted events like Tulca Festival of Visual Arts, has become a launchpad for major projects. Tulca, in particular, is known for its thematic curation and commitment to both critical discourse and artistic experimentation. Each year, it invites a curator to develop a program that connects Galway’s local scene to broader cultural or philosophical questions, fostering dialogue between artists and audiences in innovative ways.

As we look at Galway’s art scene today, what stands out is not a dominant aesthetic or medium, but a vital pluralism. Artists draw from a wide range of disciplines, identities, and philosophies, yet share a commitment to making art in community—whether that’s through shared studios, public conversations, collaborative installations, or simply the act of staying rooted in place.

Galway’s contemporary artists are not simply inheriting a tradition—they are reinventing it. Their work is fluid, questioning, and generative. It builds on centuries of visual storytelling, but speaks in new tongues: digital, decolonial, feminist, ecological. In a city where light and language are always shifting, these artists continue to ask what it means to see—and be seen—here.

Art in the Time of Festivals – Galway International Arts Festival and Beyond

Few cities wear their creative heart so publicly as Galway. Every summer, its streets erupt with color, sound, and spectacle. In shop windows, along the River Corrib, and inside old stone warehouses turned pop-up galleries, visual art surges into view—animated not just by individual artists, but by the collective electricity of festival culture. At the center of this annual burst is the Galway International Arts Festival (GIAF), founded in 1978 and now one of Europe’s most dynamic multidisciplinary events. Yet GIAF is not alone. Galway’s landscape of festivals—from grassroots gatherings to globally funded showcases—has profoundly shaped its visual culture, offering both a platform and a challenge to the artists who work within it.

When GIAF began, its ambition was modest: a city-wide celebration of music, theatre, literature, and art that could reflect Galway’s distinct personality and draw on its bilingual, bohemian character. Visual art was part of the festival from the beginning, though often in secondary venues—school halls, borrowed gallery spaces, or makeshift installations. But even then, the curatorial approach was distinct: experimental, populist, and open to artists working outside the mainstream.

Over time, as the festival matured and gained international acclaim, visual art became one of its defining features. The Festival Gallery, which emerged as a recurring venue in the early 2000s, allowed for curated exhibitions of international calibre, featuring major names in contemporary art alongside Irish artists. Its ever-changing physical location—often in temporary or repurposed spaces—mirrored the festival’s broader ethos: transformation through art.

One of GIAF’s enduring strengths has been its ability to pair visual art with performance, music, and installation in ways that dissolve disciplinary boundaries. Artists and curators have embraced this hybridity, creating immersive environments that collapse the space between viewer and artwork. Exhibitions often include video projections, soundscapes, architectural interventions, or interactive elements, turning the gallery into a site of experience rather than quiet contemplation.

International artists such as John Gerrard, Sarah Hickson, and Bill Viola have shown at GIAF, exposing Galway audiences to global conversations about surveillance, identity, migration, and spirituality. At the same time, the festival has consistently championed Irish voices, offering early-career artists a platform to exhibit alongside more established peers. The result is a multilayered ecosystem where emerging and experimental works are given space to breathe.

Beyond formal exhibitions, the streets of Galway become canvases during festival season. GIAF’s partnership with companies like Macnas, known for their colossal puppets and surreal processions, has turned the city into a living theatre of visual wonder. These spectacles—half sculpture, half performance—require teams of artists, builders, and designers, offering hands-on experience and collaboration to a wide array of local creatives.

The integration of visual art into public space during festivals has also prompted deeper civic conversations. Temporary installations in Eyre Square, along the Claddagh, or across the Spanish Arch often explore themes such as climate crisis, historical memory, and urban transformation. These works, though ephemeral, leave a lasting impression, seeding public debate and challenging perceptions of what art can do.

Other festivals have added further dimensions. TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, launched in 2002, has become Galway’s most important contemporary art-specific festival. Held each November, TULCA is curated annually around a central theme, offering a rigorous and research-driven approach to exhibition-making. Unlike GIAF, which spans all disciplines, TULCA’s focus allows for deeper engagement with emerging critical discourses in contemporary art. It frequently features installations, workshops, film screenings, and artist talks that delve into decolonial practice, feminist critique, climate politics, and speculative futures.

Importantly, these festivals don’t just exhibit art—they create conditions for artistic production. Many artists plan their projects around the festival calendar, knowing that exposure and resources may be available. Residencies tied to GIAF or TULCA provide studio space and curatorial support, while temporary grants encourage risk-taking and large-scale experimentation.

Festivals also bring audiences who may never set foot in a gallery otherwise. By embedding art into public rituals—nighttime parades, street performances, pop-up exhibitions—they democratize visual culture, inviting participation and interpretation. This accessibility, while sometimes seen as at odds with more critical or conceptual practices, is one of Galway’s great strengths: its ability to stage a conversation between high art and street life, between global trends and local experience.

Of course, the festival model also presents challenges. The focus on spectacle and temporality can strain the city’s already limited infrastructure. Pop-up spaces, while exciting, do not substitute for permanent institutions. Some artists have expressed concern that the pressure to “perform” during festival season leads to burnout or compromises slower, more research-based practices. Others note that the influx of international work can overshadow local voices if not carefully balanced.

Still, there’s no denying the transformative power of festival time in Galway. It reanimates the city, drawing on its theatrical past and its contemporary ambitions to create something electric, inclusive, and bold. For visual artists, it offers not only an audience, but a stage, a community, and a challenge: to meet the city’s energy with work that resonates, provokes, and delights.

In a place where rain can turn to light in an instant, where the streets hum with stories and music, the festival is not a break from everyday life—it is its fullest expression. Art here is not confined. It dances on walls, in crowds, under skies streaked with west-of-Ireland sun. It invites everyone in.

Galway 2020 and Its Legacy

Few moments in Galway’s recent cultural history carried as much anticipation—or as much scrutiny—as Galway 2020, when the city was named European Capital of Culture. Announced with great fanfare in 2016, the designation was heralded as a transformational opportunity: a year-long celebration that would amplify Galway’s artistic voice, invigorate its infrastructure, and connect its culture to Europe on a grander stage. For Galway’s visual artists, it promised visibility, resources, and momentum. And yet, the reality of 2020 proved more complex—marked by ambition, disarray, resilience, and, of course, the unforeseen disruption of a global pandemic.

Galway’s bid for the Capital of Culture title emphasized the city’s liminality: its position between land and sea, between languages, and between the rural and the urban. The core theme—“Making Waves”—signaled a desire to disrupt, innovate, and foreground Galway’s spirit of artistic resistance. The visual arts were to play a central role in this narrative, with plans for ambitious installations, international residencies, and a network of local and regional exhibitions spreading from the city to the Gaeltacht.

The lead-up to 2020 was filled with promise. Major projects were announced, including large-scale public art commissions, collaborations with European partners, and site-specific works designed to reimagine Galway’s built and natural environment. The Visual Arts Programme, curated initially under the “Wave” strand of the cultural strategy, was meant to be inclusive, experimental, and deeply rooted in place, giving voice to Galway’s diverse artistic community.

But from early on, logistical issues dogged the initiative. There were reports of poor communication, sudden shifts in leadership, delays in funding, and concerns from artists and collectives about a lack of transparency. Artist-led spaces like 126 Gallery and Engage Studios were eager to participate, but many felt sidelined or under-informed as the program’s details evolved. Several high-profile projects were delayed or quietly cancelled. Critics began to ask: whose culture was being celebrated, and who was left out of the frame?

Then came March 2020—and with it, the COVID-19 pandemic. The public health crisis brought live events to a halt, shuttered galleries, and suspended international travel. Overnight, the grand vision for Galway 2020 collapsed into uncertainty. But what followed was both sobering and, at times, creatively profound.

In the face of global crisis, many artists pivoted. Projects were reimagined for digital platforms. Installations were adapted for remote engagement. Some artists used the quiet to dig deeper into research, community dialogue, and slow-building work. Others, particularly those already embedded in local networks, led guerrilla-style interventions, window exhibitions, and street-level works that could be safely viewed from a distance.

Several visual art projects from Galway 2020 nevertheless left a mark. Notably:

- Hope It Rains | Soineann nó Doineann, curated by Ríonach Ní Néill, commissioned a series of weather-themed public art works that engaged deeply with Galway’s climate, mythology, and daily experience. From wearable art to weather-responsive installations, the project reflected the adaptability and humour of west-of-Ireland life.

- A Nation’s Voice, though largely under the radar due to pandemic constraints, included striking visual components, including projections and soundscapes that transformed urban and rural environments into immersive, temporary art spaces.

- Several Gaeltacht-based projects, such as those supported through the Small Towns Big Ideas initiative, highlighted the role of language and community in visual storytelling—using murals, sign-painting, and vernacular design to express local identity.

While the flagship moments of Galway 2020 may have faltered, the legacy of the year lies not in spectacle but in reflection. Artists, curators, and cultural workers in Galway gained hard-earned experience navigating institutional complexity, improvising under pressure, and advocating for accountability. For some, the shortcomings of the project confirmed the need to invest in bottom-up cultural models, rather than top-down prestige events.

Importantly, Galway 2020 drew attention to infrastructure gaps that still hinder Galway’s visual art scene: the lack of a permanent contemporary art museum, limited studio space, and precarious conditions for working artists. These conversations have not ended—they have intensified. New funding streams, arts strategy reviews, and community-led planning processes have since emerged in response to the lessons of 2020.

The emotional and symbolic impact of the year also matters. Despite everything, Galway 2020 affirmed the city’s artistic potential on a European stage. It seeded collaborations that are still unfolding. It gave artists, however briefly, a larger megaphone. And in its struggles, it laid bare the realities of cultural labor—both its fragility and its strength.

Perhaps most poignantly, Galway 2020 reminded the city that art is not just for celebration. It is also a tool for grieving, adapting, and imagining new futures. The artists who navigated that strange, disjointed year created not a spectacle but a testament: to community, improvisation, and endurance.

Now, years later, Galway’s cultural ecosystem continues to evolve—with a renewed focus on sustainable growth, equity, and local empowerment. And while Galway 2020 may not have unfolded as envisioned, it remains a defining chapter in the city’s contemporary art history—one that continues to provoke reflection, debate, and a cautious hope for what might still be possible.

Galway’s Art History as Living Heritage

To walk through Galway is to move through layers of artistic memory. Carved stone, painted shutters, theatrical posters, and new digital projections all coexist in a city that has never separated art from life. Galway’s art history is not a sealed-off archive or a collection of museum pieces; it is a living heritage, constantly being remade in the hands, eyes, and voices of those who live here.

What distinguishes Galway’s visual culture is not a single style or school, but a sensibility of permeability—to landscape, language, tradition, and experimentation. Art here is rarely produced in isolation. It listens to the wind off the Atlantic. It responds to street rhythms, festival energies, the breath of old stories told in Irish and English. It exists in thresholds: between public and private, sacred and secular, permanence and impermanence.

Looking back, we see how Galway’s art has always reflected its hybrid nature. The religious carvings of the medieval church told stories of both faith and civic identity. The heraldry of the Tribes inscribed family memory into limestone walls. The folk art of the 18th and 19th centuries wove resilience into cloth and domestic objects. The Celtic Revival reimagined old symbols for a modern nation. The theatres became stages not just for performance but for visual drama, pageantry, and protest. And in our own time, collectives, festivals, and community projects keep those creative fires burning—not as tradition for its own sake, but as fuel for reinvention.

Galway’s art heritage is also intergenerational. Elders pass on techniques and textures; younger artists remix them. Institutions like GMIT (now part of ATU), artist-run spaces like 126, and festivals like TULCA and GIAF serve as bridges between past and future, between local identity and international discourse. These structures are imperfect and evolving, but they form the scaffolding on which Galway’s art continues to grow.

The city’s Gaeltacht connection remains vital. In an age of globalization and cultural flattening, the Irish language provides not just content but form—a rhythm, a worldview, a way of seeing. Visual artists increasingly engage with Gaeilge not just as subject but as medium, challenging dominant narratives and offering alternatives to Anglophone aesthetic codes. This linguistic interplay is part of what keeps Galway’s visual culture so richly textured.

At the same time, Galway’s artists confront contemporary challenges: the housing crisis, gentrification, climate change, cultural commodification. Many of the same issues that threaten artists in other cities are felt acutely here—perhaps more so, given Galway’s rapid growth and still-limited arts infrastructure. Yet it is precisely in this tension that art finds its urgency. Whether through public installations, activist collectives, or quietly introspective paintings, Galway’s artists remain deeply engaged with their world.

Importantly, Galway’s art history is not static or exclusive. It is being rewritten every day—by migrant artists, queer artists, neurodivergent artists, artists working in new media, or speaking new tongues. Their stories are just beginning to be woven into the broader tapestry. And as Galway continues to shift demographically and economically, so too will its art shift—responding, resisting, remaking.

What this deep dive has revealed is not just a chronicle of styles and figures, but a sense of continuity: of art as a force of belonging, questioning, and renewal. Galway’s visual culture is alive because it belongs to no one group. It grows where language meets land, where stone meets story, where the personal meets the public. It has always been an art of thresholds—and in that, it offers a model for what art can be: porous, participatory, rooted, and radically alive.

To study Galway’s art history, then, is not just to look back. It is to join a conversation already in progress. It is to listen. To watch. To walk.

And perhaps, to make something of your own.