There’s a rhythm to Melbourne that pulses with creativity. Stroll through its laneways, and you’ll encounter not only the scent of espresso or the echo of trams but also an explosion of color, texture, and visual storytelling. Art is stitched into the very fabric of this city, not as an afterthought or a tourist trinket, but as a living, breathing identity. Melbourne doesn’t just support art—it embodies it.

To understand Melbourne as an artistic epicenter, one must begin with its foundational paradox: a city born from colonial ambition, yet now known for progressive expression. Melbourne’s art history is both a reflection of, and reaction to, the social, political, and cultural currents that have shaped it over nearly two centuries. From its early mimicry of European tastes to the bold, unapologetically local art movements it birthed, the city has evolved into Australia’s most vibrant visual arts hub.

Melbourne has long jostled with Sydney for cultural dominance, but when it comes to the visual arts, many argue the southern capital reigns supreme. The evidence is in its institutions: the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the oldest and one of the largest public art museums in the country, draws millions annually with blockbuster exhibitions and contemporary showcases. The Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), with its striking rust-colored facade, presents boundary-pushing installations that challenge the very definition of art. Beyond these pillars, a constellation of smaller galleries, artist-run spaces, and pop-ups animate the inner suburbs and outer fringe alike.

But Melbourne’s claim to artistic centrality isn’t just institutional—it’s street-level. Its famed laneway culture is globally renowned, with artists turning neglected alley walls into dynamic, ever-changing galleries. Names like Rone, Adnate, and Lushsux—once underground figures—are now internationally recognized, their styles woven into the global urban art conversation. Street art in Melbourne isn’t graffiti—it’s heritage, with places like Hosier Lane treated with the same reverence as a museum wing.

This city also has a unique relationship with time. There’s a continuity between the historic and the avant-garde here, where Heidelberg School landscapes coexist with digital installations and VR-driven experiences. Melbourne doesn’t erase its past; it curates it, integrates it. The Heide Museum of Modern Art, once a haven for modernist artists in the mid-20th century, now functions as both a time capsule and a contemporary space. Similarly, older buildings repurposed as studios and galleries—like the Nicholas Building—foster a spirit of artistic rebellion inside structures once built for commerce.

Diversity, too, is a key driver of Melbourne’s artistic energy. Waves of immigration—from Southern Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa—have continually reshaped the cultural terrain. The result is a visual arts scene as eclectic as it is inclusive, with exhibitions often featuring diasporic perspectives, postcolonial critiques, and hybrid identities. Multicultural festivals like Next Wave or Melbourne Fringe spotlight voices from the margins, foregrounding experimental and non-Western practices that redefine the mainstream.

Melbourne’s art scene also thrives on dialogue—between artist and audience, history and present, local and global. The city encourages artists to ask difficult questions, and institutions rarely shy away from controversy. From Aboriginal rights to climate change, from gender politics to urban displacement, Melbourne’s art isn’t just beautiful—it’s often biting, political, and necessary.

It’s no surprise, then, that artists come to Melbourne not just to exhibit, but to live, teach, learn, and organize. The city offers a fertile ground for both emerging and established artists, buoyed by an infrastructure of residencies, grants, public art commissions, and critical platforms. Art is treated as a civic asset—part of the city’s strategic vision as much as its cultural character.

In short, to call Melbourne an artistic epicenter is not just a nod to its galleries or famous names. It’s a recognition of a living ecosystem, sustained by artists, institutions, audiences, and the city itself. It is not a stage where art is displayed—it is a collaborator in the creative act.

Aboriginal Art and the Wurundjeri People

Long before Melbourne became a city, before the arrival of European settlers or the construction of galleries and laneways, this land was home to the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. Their deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land forms the earliest chapter of Melbourne’s art history—a story told not on canvas or gallery walls, but through ceremony, body art, rock engraving, weaving, and ephemeral installations etched into the land itself.

Indigenous art is not merely decorative or symbolic; it is an integrated system of knowledge, storytelling, law, and cosmology. In the case of the Wurundjeri, art was (and is) a way to record and transmit the Dreaming—ancestral narratives that connect people to Country and to each other. These stories are encoded in forms that may appear abstract to a Western eye but are densely layered with meaning, lineage, and responsibility.

Prior to colonization, Wurundjeri art was intimately tied to seasonal movement, ritual, and intergenerational teaching. Designs were inscribed on bark, shields, and skin, with patterns often reflecting moieties, clan affiliations, and spiritual beings. The land itself was treated as a living canvas: scarred trees marked ceremonial significance; ochre rock art sites told stories of creator spirits and battles. Many of these traditions were shared orally and through performance, in what we might now recognize as interdisciplinary or multimedia practices, though Indigenous modes defy such categorizations.

The arrival of European settlers in the 1830s drastically disrupted these systems. The Wurundjeri, like many Indigenous groups, were forcibly displaced from their land, subjected to missions and reserves, and their cultural practices systematically suppressed. Yet art endured—sometimes hidden, sometimes transformed. Through crafts, drawing, and adapted materials, many Aboriginal artists found new ways to preserve stories and identity amid colonial trauma.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that Indigenous art in Melbourne began receiving significant public recognition. This resurgence owes much to the efforts of community leaders, cultural workers, and artists who insisted that Indigenous voices belonged not just in anthropological museums, but in mainstream art spaces. Organizations like the Koorie Heritage Trust, established in 1985, have been pivotal. Located on the banks of the Birrarung (Yarra River) in Federation Square, the Trust offers a space where contemporary Aboriginal artists exhibit alongside historical objects and community archives. It’s a site of cultural memory and artistic innovation, reclaiming urban space for Indigenous expression.

Contemporary Wurundjeri and other Victorian Aboriginal artists now draw on both traditional motifs and modern mediums to tell stories of survival, sovereignty, and place. Artists like Vicki Couzens, Kent Morris, and Maree Clarke weave ancestral knowledge with photography, installation, and digital art. Clarke, in particular, has been instrumental in reviving cultural practices such as kangaroo tooth necklaces and possum skin cloaks—objects once suppressed under assimilation policies, now proudly exhibited at the NGV and beyond.

These cloaks deserve special mention. Once worn for warmth and ceremony, each cloak tells a story—etched and burned into the skin with symbols representing landscape, kinship, and journey. The revival of cloak-making in Victoria is a powerful act of cultural resurgence, reconnecting communities with lost knowledge and reaffirming identity in a settler-colonial context.

Melbourne’s art institutions have begun—though belatedly and often imperfectly—to acknowledge this history. Major galleries now feature Indigenous curators and dedicate space to Aboriginal art not as a sidebar but as a central narrative. The NGV’s Indigenous Art Department, led by figures like Judith Ryan, has helped reframe these works not just as “ethnographic” but as contemporary, critical, and essential. More recently, initiatives like Yalingwa, a curatorial partnership between Creative Victoria, ACCA, and TarraWarra Museum of Art, have empowered First Nations curators to shape exhibitions from their own perspectives.

Yet challenges remain. Indigenous artists in Melbourne often navigate a complex terrain of expectation—tasked with representing “authentic” culture while also being experimental or critical. The tension between artistic autonomy and cultural responsibility is ever-present, especially in a city where the land is still unceded, and where gestures of recognition often outpace material change.

Still, the fact that Wurundjeri and other First Nations artists are shaping Melbourne’s art scene—through biennales, public art commissions, residencies, and protests—is a testament to resilience. Art here is not only an aesthetic gesture but an assertion of sovereignty, a form of healing, and a tool of truth-telling.

To understand Melbourne’s art history without centering the Wurundjeri is to miss its beginning, its heartbeat, and its future. As artist and scholar Tony Birch writes: “Country has always been inscribed with memory… We carry that in the work, in the story, in the way we live.” In Melbourne, that inscription continues.

Colonial Foundations: Art in the 19th Century

When the British arrived on the banks of the Yarra River in 1835, what they saw they interpreted not as a homeland already occupied, but as a blank canvas. In their eyes, this so-called “new world” lacked history, aesthetics, and order—an absence they were determined to fill. With settlers came surveyors, with surveyors came draughtsmen, and with draughtsmen came artists—each tasked, implicitly or explicitly, with recording, domesticating, and romanticizing the Australian landscape.

In the early years of Melbourne’s colonization, art served an administrative and documentary purpose. Topographical sketches were tools of empire, depicting land as property to be claimed and cultivated. Figures like John Cotton and Robert Hoddle produced illustrations that were as much maps as they were artworks, often erasing Indigenous presence in the process. This visual language of “terra nullius”—the legal fiction that justified British colonization—was not just written in law but drawn into public consciousness through paintings and prints.

But as Melbourne grew from outpost to metropolis during the mid-19th century, a more ambitious artistic culture began to take shape. The discovery of gold in Victoria in the 1850s brought immense wealth, swelling the city’s population and filling the coffers of private collectors and public benefactors. With wealth came patronage, and with patronage, institutions. In 1861, just two decades after Melbourne’s founding, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) was established—becoming the oldest public art museum in Australia. It symbolized not only civic pride but an aspiration to cultural legitimacy.

The NGV’s early acquisitions were telling. The focus was heavily Eurocentric, filled with neoclassical sculpture, Biblical scenes, and works from the Royal Academy. Melbourne’s upper class sought to transplant the cultural prestige of London or Paris to this new city on the other side of the world. Art in this period was both mirror and mask: a reflection of British tastes and a performance of refinement in a still-raw colony.

Portraiture thrived in this environment. Colonial elites commissioned likenesses to assert status, while artists like Nicholas Chevalier, Eugene von Guérard, and Thomas Clark emerged as some of the first recognizably “Australian” painters—even as they remained steeped in European aesthetics. Von Guérard, in particular, is an essential figure of this era. Trained in the Düsseldorf school, his landscapes of Victoria combined precise scientific observation with a Romantic sublime. His paintings of Mount Kosciuszko and the Dandenong Ranges are not just beautiful—they were ideological, casting the land as majestic, empty, and awaiting cultivation.

It’s crucial to note what was being left out of these images. Indigenous people were largely invisible in colonial art—or, if present, were rendered as noble savages or passive observers, fading into the background of a vanishing world. This visual erasure mirrored the physical violence of frontier conflict and land dispossession. The arts, consciously or not, were complicit in crafting a myth of peaceful settlement.

Yet beneath the dominant narratives, countercurrents began to stir. Some artists, influenced by the growing social reform movements of the late 19th century, started to challenge the idealized vision of colonial life. Paintings began to depict not just pastoral bliss but urban hardship, environmental change, and the roughness of bush existence. This shift laid the groundwork for a more distinctly Australian visual language—one that would find fuller expression in the coming decades with the Heidelberg School.

By the 1880s and 1890s, Melbourne had become one of the wealthiest cities in the British Empire, a “Marvellous Melbourne” of ornate buildings, gaslights, and opera houses. Art exhibitions flourished, and institutions like the Victorian Academy of Arts (later merging into the Victorian Artists Society) became key forums for exhibition and debate. Public lectures, artist societies, and private galleries helped expand both production and appreciation of art.

Importantly, this period also saw the emergence of art education in a more formalized sense. The National Gallery School—later to become part of the VCA—began training local artists, introducing life drawing classes and encouraging students to look beyond imitation toward experimentation. This institution would prove pivotal in shaping several generations of artists who would define Australian art in the 20th century.

Still, the 19th century closed with unresolved tensions. Art in Melbourne had evolved from mere documentation to aesthetic expression, but it was still shackled to the tastes and hierarchies of empire. It would take a new generation of artists—rooted in this soil, inspired by this light, and disillusioned with European affectation—to break away and articulate something truly local. That revolution would come on the banks of the Yarra, in paddocks just beyond the city, with easels in the grass and paint boxes open to the wind.

The Gold Rush Boom and Its Aesthetic Impact

If the 19th century gave birth to Melbourne, the Gold Rush of the 1850s raised it in opulence. In just a few decades, this once-humble colonial settlement became one of the richest cities in the world. Streets were paved, grand buildings rose, and with newfound wealth came a hunger for culture. Art—once the pastime of a sparse colonial elite—suddenly became a civic project, a public symbol of Melbourne’s ascent into modernity.

The goldfields of Ballarat and Bendigo didn’t just yield riches; they reshaped the cultural economy of Victoria. By the late 1850s, Melbourne was awash in capital, much of it speculative, entrepreneurial, and anxious for recognition. Gold tycoons, merchants, bankers, and landowners turned their fortunes into philanthropic gestures, eager to emulate the prestige of London, Paris, or Vienna. Funding a gallery, endowing a collection, or commissioning public art became a way to solidify one’s legacy—and to civilize what many still saw as a rough, frontier society.

This period saw the expansion of major cultural institutions. The National Gallery of Victoria, founded in 1861, was arguably the crown jewel of this new era. It was financed by both government support and private donations—most notably from Alfred Felton, whose posthumous bequest in 1904 would become the single most influential act of art philanthropy in Australian history. Felton’s bequest allowed the NGV to acquire European masterpieces at a scale and pace unmatched in the Southern Hemisphere. While his impact came slightly after the peak of the gold rush, it was built on the economic foundations that the gold boom had secured.

Beyond the NGV, Melbourne saw a flurry of gallery activity. Art societies, exhibition halls, and academy schools sprang up, offering both venues for artists to show their work and for patrons to acquire it. The Victorian Academy of Arts, the forerunner of the Victorian Artists Society, held regular exhibitions and helped foster a local scene that, for the first time, began to rival imported European works in popularity and critical respect.

The influx of wealth also meant that artists could now make a living from their work, a shift from earlier decades when artistic practice was more often a hobby or side profession. As a result, Melbourne became a magnet for talent—from within Australia and abroad. Immigrant artists brought with them European training, while locally born artists began to develop new, uniquely Australian approaches to subject matter and style.

But the gold rush didn’t just fund art—it reshaped the aesthetic imagination of Melbourne. The city’s rapid transformation was mirrored in its buildings, streetscapes, and visual culture. Architects embraced high Victorian grandeur, constructing elaborate public buildings, arcades, and town halls. These spaces were designed not only to impress but to inspire civic pride, embedding beauty into everyday life. The famed Royal Exhibition Building, completed in 1880 to host the Melbourne International Exhibition, was both an architectural marvel and a stage for cultural exchange—hosting art from across the empire and beyond.

Visual representations of the gold rush itself also became part of the artistic record. Paintings and prints depicted bustling diggings, hopeful miners, and chaotic camps—sometimes romanticized, sometimes raw. Works like Edward Roper’s “Gold Diggings, Ararat” (1854) capture the gritty hope of the era, while S.T. Gill’s watercolours offered a more populist, often humorous view of life on the fields. These images not only documented an economic revolution—they shaped the mythology of colonial Australia.

Ironically, this same boom exposed the deep inequalities at the heart of Melbourne’s prosperity. As the city gleamed with galleries and statuary, Indigenous communities faced worsening displacement, and working-class neighborhoods grappled with overcrowding, pollution, and poverty. Yet, art seldom reflected this dissonance—at least not yet. The aesthetics of the gold rush era largely celebrated order, grandeur, and progress, presenting a vision of harmony that papered over the fractures beneath.

The opulence of this time also introduced the concept of art as national identity. The more confident Melbourne became economically, the more it sought to express a uniquely “Australian” sensibility through its cultural production. Landscape painting flourished—forests, mountains, and sunlit pastures became the canvas upon which the colonial project wrote its triumphs. The visual language of this period laid the groundwork for what would soon become Australia’s first major art movement: the Heidelberg School.

In the end, the Gold Rush wasn’t just a financial windfall—it was an aesthetic catalyst. It gave Melbourne the institutions, the infrastructure, and the self-confidence to become a center of art in the Southern Hemisphere. While its artistic legacy was, at times, conservative and Eurocentric, it built the foundations—both literal and conceptual—upon which future waves of rebellion, experimentation, and renewal would be constructed.

The Heidelberg School: Australia’s First Art Movement

In the late 1880s, something remarkable began to stir in the outer suburbs of Melbourne. On the banks of the Yarra River, among the bushland of Heidelberg and Eaglemont, a group of young painters set out to do something no one in Australia had done before: capture the land as it truly looked, and as it felt. No grand European pastures, no mythic allegories—just the raw, golden light of an antipodean afternoon, eucalyptus smoke drifting through dry air, and workers at rest beneath the gum trees. What they created was more than a style—it was a movement, one that would become known as the Heidelberg School.

Often called the Australian Impressionists, the artists of the Heidelberg School were not simply mimicking the French. While they were inspired by Impressionism’s loose brushwork and focus on natural light, their ambitions were rooted in place and identity. They sought to forge a national art—one that reflected the unique geography, climate, and culture of a rapidly maturing Australian colony. In doing so, they helped shape the visual foundation of what Australians would come to think of as their own.

At the heart of the movement were figures like Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin, and Charles Conder—painters who met through the National Gallery School in Melbourne and who, despite diverse influences, shared a common purpose. In 1888, they established a kind of open-air studio in a weatherboard cottage in Heidelberg. Here, they painted en plein air—outdoors, directly in the landscape, often in intense heat and over long days. The method was radical for its time in Australia and perfectly suited to capturing the shimmering dryness of the bush, the wide skies, and the warmth of the light.

One of the most iconic works of this period is Arthur Streeton’s “Golden Summer, Eaglemont” (1889), a painting that captures a parched hilltop overlooking farmland, washed in golden haze. The brushwork is quick and expressive, the atmosphere luminous. It isn’t just beautiful—it’s resolutely local. No attempt is made to Europeanize the scene or idealize it in neoclassical terms. This was the world as Streeton saw it, and as countless Australians had lived it.

Tom Roberts, often seen as the intellectual leader of the group, brought a strong social consciousness to the movement. His works, like “Shearing the Rams” (1890), combined nationalist sentiment with an almost documentary sense of realism. In these paintings, labor becomes iconic: the shearing shed a kind of cathedral, the workers dignified and enduring. These were not aristocrats or mythological figures—they were everyday Australians, and they were rendered with affection, seriousness, and skill.

Frederick McCubbin, meanwhile, brought a more introspective, even melancholic tone to the movement. In paintings like “The Pioneer” (1904), he layered bush landscapes with emotional narratives—telling stories of migration, struggle, and memory. His work was deeply engaged with the settler experience, often idealizing resilience while also acknowledging loneliness and loss.

Together, these artists forged a vision of Australia that was earthy, luminous, and sincere. They painted what was around them—sunlit paddocks, dusty roads, billabongs, and campfires—but imbued those scenes with emotional weight and symbolic depth. Their work was both a celebration and an invention of national identity, arriving at a time when Australia was nearing Federation (1901) and beginning to define itself outside of British rule.

Melbourne was central to the movement’s genesis. The city’s galleries, collectors, and critics gave the artists platforms, while the surrounding bushland offered both inspiration and refuge. In fact, while the group painted in places like Box Hill, Heidelberg, and even as far afield as Sydney and New South Wales, it was the Melbourne art world that first recognized their importance and helped cement their legacy.

Critically, the Heidelberg School was also a turning point in how Australians thought about the land. Earlier colonial art often depicted the bush as dark, threatening, and unfamiliar—a place to be conquered. The Heidelberg painters reimagined it as beautiful, vital, and distinctly Australian. Their legacy was a shift not just in technique, but in national perception.

However, the movement wasn’t without its blind spots. The Australia depicted in these works was overwhelmingly white, male, and settler-focused. Aboriginal presence was absent or relegated to myth. Women appeared infrequently, and when they did, it was often in domestic or romanticized roles. These exclusions would later become points of critique by feminist, Indigenous, and postcolonial scholars and artists seeking to rewrite and expand the national narrative.

Still, the Heidelberg School left an indelible mark. Its influence extended through the 20th century, and its key works became national icons, reproduced in textbooks, postage stamps, and tourism campaigns. The National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of New South Wales still dedicate significant space to these artists, and their paintings continue to resonate, even as contemporary artists interrogate their limitations.

In essence, the Heidelberg School captured a moment: a time when Melbourne’s artistic community stepped out from behind Europe’s shadow and began to see, and paint, Australia through Australian eyes.

Federation and National Identity Through Art

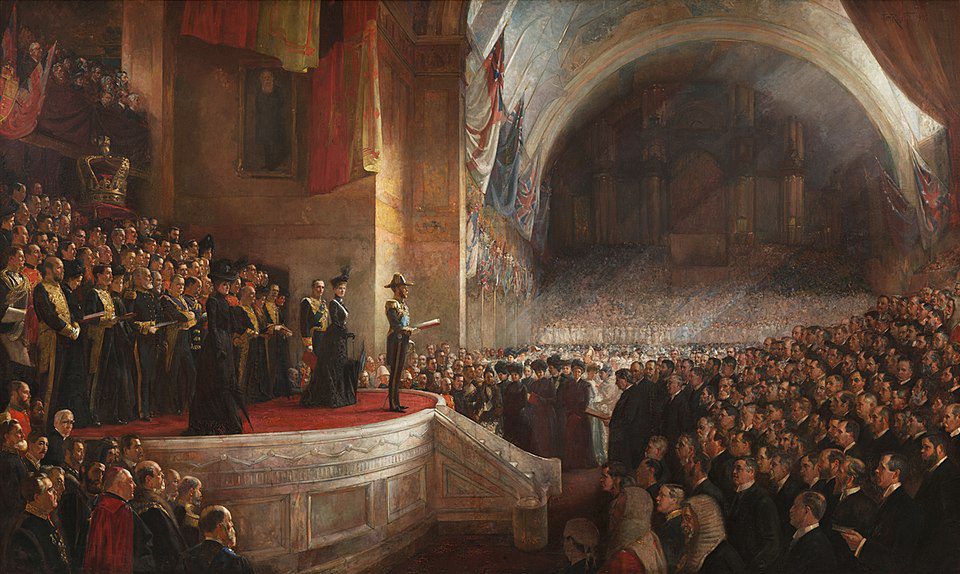

At the turn of the 20th century, a profound transformation was sweeping the Australian colonies. In 1901, after decades of political wrangling, six separate colonies federated into a single nation: the Commonwealth of Australia. It was a moment charged with symbolism, aspiration, and uncertainty. What did it mean to be Australian? What did the nation look like, feel like, believe in? As politicians debated constitutions and governance, artists quietly set about crafting something arguably more powerful: a visual language of national identity.

Melbourne, the interim capital of the newly federated country until Canberra’s construction, was at the epicenter of this cultural project. The city’s artists, galleries, and institutions were uniquely positioned to help visualize what a new nation could be. Art in the early Federation period became an exercise in myth-making, full of pride, pathos, and profound contradictions.

In many ways, the Heidelberg School had already laid the groundwork. Their sun-drenched landscapes and depictions of rural labor had resonated deeply with a population seeking roots in their adopted land. Paintings like Tom Roberts’ “Shearing the Rams” or Arthur Streeton’s “Fire’s On” were not just admired—they were interpreted as national allegories: the bush worker as citizen, the outback as homeland, the rural ideal as the moral core of the nation.

This pastoral nationalism became a powerful motif in Federation-era art. The bush was elevated to near-mythic status, standing in contrast to the perceived decadence of Europe and the urban sprawl of cities. In the Federation imagination, Australia was honest, hard-working, egalitarian—qualities symbolized by the land and its people, despite the fact that most Australians were already living in cities like Melbourne and Sydney.

Artists continued to develop this imagery, but with more polish and sometimes more ambiguity. Painters like George W. Lambert brought a refined academic realism to national subjects, combining classical techniques with uniquely Australian content. His “Across the Black Soil Plains” (1899), for instance, transforms a team of draft horses dragging a wagon across harsh terrain into an epic of perseverance.

Melbourne’s institutions played a crucial role in framing these works for public consumption. The National Gallery of Victoria, in particular, doubled down on its mission to collect and exhibit works that reflected national identity. While still acquiring European art—thanks in part to Alfred Felton’s transformative bequest—the NGV also expanded its collection of Australian artists, helping to establish a canon and give local art a sense of continuity and legitimacy.

Yet the vision of Australia these early 20th-century artworks promoted was far from inclusive. The art of Federation was built on a settler narrative that erased or ignored Indigenous peoples. Aboriginal Australians, whose cultures had endured on this land for tens of thousands of years, were almost completely absent from the national visual lexicon. When they did appear, they were often romanticized, depoliticized, or rendered as vanishing relics of a pre-modern world.

Similarly, the role of women in shaping the cultural identity of the nation was often diminished in the mainstream narrative. Though many female artists were active—Jane Sutherland, Clara Southern, Margaret Preston, and May Gibbs, to name just a few—they struggled for recognition and institutional support. Their work, often focused on domestic scenes, native flora, or folklore, provided important counterpoints to the masculine bush mythology dominating public art.

Despite these limitations, the Federation period did see experimentation and the emergence of new voices. Movements like Art Nouveau and early Modernism began to ripple into Australian studios, especially through immigrant artists or those who had studied abroad. Melbourne became a kind of cultural crossroads, absorbing ideas while still clinging to a British artistic lineage.

World events also left their mark. The Boer War, and later the First World War, challenged the idealized vision of the strong, free Australian man that had dominated visual culture. Artists began grappling with the trauma of warfare, the costs of empire, and the fragility of national pride. This was particularly evident in post-WWI memorial sculpture and in works by returned soldier-artists, whose experiences clashed with the pastoral idealism of the 1890s.

Nevertheless, the early decades of the 20th century remained deeply invested in the project of defining and projecting an Australian character. This effort was mirrored in literature, music, and theatre, but visual art had a unique power: it could render the myth in color and shape, freeze it in brushstrokes, hang it on the walls of civic halls and schools. Art became a national mirror—not always accurate, but compelling in its reflection.

Melbourne’s role in this cultural construction was foundational. It hosted major exhibitions, housed the country’s leading art school, and maintained a steady flow of public and private investment in the arts. As Australia moved further into the 20th century, however, new voices would emerge—voices that questioned, resisted, and reimagined what “Australian art” could be.

Modernism in Melbourne: Rebellion and Reinvention

By the 1920s, the golden haze of the Heidelberg School and the pastoral nationalism of Federation-era art were beginning to feel dated—picturesque, certainly, but ill-equipped to confront the complexities of a new century marked by war, industrialization, and cultural upheaval. Melbourne, once comfortable in its role as custodian of colonial elegance, became a city divided between tradition and rebellion. And out of this friction, Modernism arrived—not with a single manifesto, but in waves, critiques, and creative revolts that gradually remade the city’s artistic DNA.

The early 20th century was a time of profound contradiction in Australian art. On one hand, institutions like the National Gallery of Victoria remained committed to academic realism and European traditions. On the other, a restless generation of younger artists—exposed to new ideas through travel, emigration, and literature—began to question the old order. They sought not only new techniques but new ways of seeing. This was more than a stylistic shift; it was a philosophical and political rupture.

At the forefront of this transformation was George Bell, a central figure in Melbourne’s modernist awakening. A painter, teacher, and critic, Bell had studied in Paris and London, bringing back with him the ethos of Cézanne, Matisse, and the Post-Impressionists. In the 1930s, he established the George Bell School in Melbourne, a studio that became ground zero for a modernist rebellion. There, Bell preached the virtues of form, abstraction, and intellectual rigor, positioning himself in direct opposition to what he saw as the sentimentality of Australian Impressionism.

His students—many of whom would go on to shape mid-century Australian art—included Russell Drysdale, John Perceval, and Fred Williams. Though their styles diverged over time, they shared a commitment to breaking with the past, refusing the easy nostalgia of gum trees and bushrangers in favor of psychological depth, social critique, and formal innovation.

But Melbourne’s modernism was never a simple import of European trends. Rather, it was a hybrid phenomenon, influenced not only by Paris and London but by the distinctive conditions of Australian life. The starkness of the landscape, the isolation of the continent, and the tension between urban and rural identities all found expression in modernist art. For instance, Albert Tucker’s angular, surrealist works like “Images of Modern Evil” reflect a postwar disillusionment with modern society, while still rooted in distinctly Australian iconography—pubs, soldiers, and street corners gone sinister.

In many ways, the crucible for Melbourne’s modernist identity was the 1940s, a decade shaped by the upheaval of World War II and the arrival of émigré artists fleeing fascism in Europe. These immigrants—many of them Jewish intellectuals and creatives—brought with them avant-garde ideas, Bauhaus training, and a deep engagement with the politics of art. Figures like Yosl Bergner, Danila Vassilieff, and Mirka Mora helped reshape the Melbourne art scene, introducing expressionism, symbolism, and narrative to a cultural landscape still reckoning with its provincialism.

Vassilieff and Mora in particular became catalysts for community and collaboration. Vassilieff’s home in the outer suburb of Warrandyte was a haven for young artists, while Mora’s café, Balzac, in East Melbourne became a legendary bohemian hub, blurring the boundaries between life, food, and art. These spaces embodied a kind of intellectual cosmopolitanism that set Melbourne apart from the more commercial or institutional tone of Sydney.

It wasn’t all harmony, of course. Modernism in Melbourne ignited intense debate and backlash, especially from more conservative quarters. In 1939, the infamous “Art War” erupted when Bell and his followers launched a campaign against the NGV’s conservative selection processes, accusing the institution of ignoring contemporary innovation. The debate spilled into newspapers, parliament, and public consciousness, revealing how seriously Australians were beginning to take their art—and how contested the idea of national culture had become.

Another major moment came in 1943, when William Dobell’s portrait of Joshua Smith won the Archibald Prize in Sydney. Though not a Melburnian event per se, the ensuing controversy over whether the work was “a caricature” or “a portrait” echoed loudly in Melbourne, where questions about realism, abstraction, and artistic freedom were already simmering. The public—and the press—were beginning to realize that art was no longer just a matter of taste. It was a proxy for ideology, identity, and change.

Melbourne’s modernists also engaged directly with political themes. In the aftermath of war and during the rise of Cold War anxieties, art became a vehicle for social critique. Some aligned with socialist realism, others explored existential dread, but all sought to connect their practice to the world outside the frame. This political edge distinguished Melbourne’s modernism from the more decorative or commercial strains emerging elsewhere.

By the 1950s, Melbourne was no longer just reacting to global trends—it was generating its own, carving out a modernist voice that was uniquely Australian. The founding of the Museum of Modern Art Australia (MOMAA) in 1958 by collector John Reed (and later integrated into the Heide Museum of Modern Art) signaled a maturation of the movement. Heide itself—a former dairy farm turned intellectual commune—hosted artists like Sidney Nolan, Joy Hester, and Sunday and John Reed, whose patronage and politics helped shape postwar visual culture.

In the end, Melbourne’s embrace of modernism was a kind of cultural reckoning. It asked: What should Australian art be? Who decides? And how does a city define itself not by what it inherited, but by what it dares to invent?

The Rise of Public Art and Street Culture

By the 1970s, Melbourne’s art world was undergoing another transformation—this time from the inside out. The avant-garde had already disrupted traditional institutions, and now a new wave of artists began rejecting even those modernist frameworks. Instead of looking to Paris or New York, they looked to the streets, the suburbs, the laneways. They painted on walls, pasted posters on telephone poles, and turned empty buildings into installations. Art was no longer confined to the gallery—it was becoming public, participatory, and political.

The roots of Melbourne’s public art culture are complex. On one hand, there was a growing awareness that the city could function as a canvas—an aesthetic environment as worthy of attention as the works hanging in the NGV. On the other, artists were pushing back against what they saw as the elitism and inaccessibility of traditional institutions. Public space, they argued, belonged to everyone, and art in public should reflect that.

The 1970s and 1980s saw an explosion of community murals, many of them driven by grassroots collectives and activist groups. These early projects often had strong political overtones, reflecting the feminist movement, unionism, Indigenous land rights, and LGBTQ+ liberation. Murals became a tool of visibility and protest, as seen in the bold, figurative work produced in neighborhoods like Fitzroy, Collingwood, and Northcote.

Artists like Megan Evans, Judy Watson, and collectives such as The Women’s Art Register helped bridge the gap between institutional and public practices, often bringing critical theory and feminist discourse to the streets. Murals weren’t just decoration—they were visual essays, challenging the dominant narratives of who the city was for and what history it should remember.

By the 1990s, another kind of street art began to emerge—one rooted not in murals or state-funded projects, but in underground movements more closely aligned with graffiti, stenciling, and tagging. Influenced by New York hip-hop culture, skateboarding, and punk DIY aesthetics, a younger generation of artists began using spray paint and wheatpaste as their media of choice. This new wave was fast, unsanctioned, and ephemeral—born out of rebellion but quickly gaining traction as a legitimate form of artistic expression.

Hosier Lane, once an overlooked alley behind Federation Square, became the symbolic heart of this movement. Layered with tags, throw-ups, characters, and political messages, its ever-changing walls turned the space into a kind of urban palimpsest. Artists like Sync, Ha-Ha (Regan Tamanui), Rone, Adnate, and Lushsux rose to prominence here, each developing distinctive styles that would earn them national—and often international—recognition.

Some, like Rone, moved from paste-ups of beautiful, decaying faces into immersive installations, turning abandoned buildings into art experiences filled with faded glamour and haunting memory. Others, like Adnate, brought a strong social justice lens to their work, painting massive portraits of Indigenous Australians on city towers, water tanks, and community centers. His towering murals in Collingwood and Fitzroy are now landmarks—not just for their technical skill, but for the narratives they insist on making visible.

The line between vandalism and art blurred constantly, sparking debates about ownership, aesthetics, and civic pride. Melbourne’s city government, after initial crackdowns, began to embrace the movement—sanctioning murals, launching street art festivals, and even incorporating works into tourism campaigns. The City of Melbourne’s Public Art Program, founded in 1994, played a key role in legitimizing public art, commissioning both ephemeral and permanent works and engaging local communities in the process.

This shift from underground to institutional recognition didn’t come without tension. Some artists resisted the co-optation of street culture, worried that spontaneity and critique would be replaced by market-driven commissions. Others saw opportunity: a chance to reach larger audiences, be paid for their work, and influence urban aesthetics more directly.

Meanwhile, public sculpture also gained momentum. Installations like Vault (better known as the “Yellow Peril”) by Ron Robertson-Swann, and Deborah Halpern’s “Angel” in Birrarung Marr, became flashpoints for public taste and discourse. These works weren’t just decoration—they sparked conversation, criticism, and sometimes even protest. Melbourne’s identity as a “city of art” was increasingly tied not just to what was inside museums, but what could be encountered on a street corner or in a train station.

Importantly, the rise of street art coincided with a broader shift in how cities understood themselves. As manufacturing declined and the service economy grew, Melbourne leaned into creative industries, cultural tourism, and place-making as economic strategies. Art—especially the accessible, Instagrammable kind—became a selling point, a sign of urban cool.

Yet the soul of the movement remained insurgent. Street art in Melbourne continues to address housing justice, gentrification, Indigenous sovereignty, and climate crisis. Artists use walls to mourn, to mock, to remember. They paint when the city sleeps and when it celebrates. And in doing so, they remind us that art doesn’t need a frame to be powerful.

Contemporary Aboriginal Art

If the early history of Melbourne’s art scene was marked by the erasure of Indigenous voices, then the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a vital and ongoing correction—a resurgence not only of artistic practice, but of cultural presence, political agency, and sovereign storytelling. Indigenous artists in Melbourne today are not merely participating in the art world; they are actively reshaping it, challenging colonial narratives, reasserting connection to Country, and offering new ways to imagine the past, present, and future.

This resurgence is not accidental. It is the result of sustained advocacy, community-building, and a refusal to be sidelined. It also builds on generations of cultural practice that survived despite systemic attempts at suppression. For the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation—the traditional custodians of the land on which Melbourne sits—this reclamation of space has been both symbolic and tangible.

A cornerstone of this cultural reassertion is the Koorie Heritage Trust, established in 1985 and now housed in the heart of Federation Square. Its mission is clear: to promote, support, and celebrate the living cultures of Aboriginal peoples from South-Eastern Australia. Unlike many institutions, the Trust is not a gallery looking in on Indigenous culture from the outside; it is a cultural space governed and run by Indigenous people, showcasing both traditional and contemporary work. Exhibitions here range from photography to digital installations to fashion, each rooted in culture but globally resonant.

Melbourne is also home to a growing cohort of First Nations artists who straddle multiple mediums and disciplines. Maree Clarke, a Mutti Mutti, Yorta Yorta, BoonWurrung, and Wamba Wamba artist, has been instrumental in reviving cultural practices that were once outlawed or forgotten. Her work brings traditional object-making into the present—possums-skin cloaks, kangaroo tooth necklaces, river reed necklaces—recreated with forensic precision and deep reverence. When Clarke’s massive installations are shown at the NGV or ACCA, they don’t just beautify space—they reindigenize it.

Other powerful voices include Christian Thompson, a Bidjara man whose conceptual photography and video art explores identity, language loss, and queer Indigenous perspectives; Kent Morris, a Barkindji artist whose digitally manipulated photographs transform urban architecture into patterns reflecting traditional motifs; and Reko Rennie, whose neon colors, graffiti-influenced style, and large-scale murals boldly assert Aboriginal identity in public spaces.

Reko Rennie’s work is particularly emblematic of the current moment. His massive text-based mural “Remember Me” (2020), created in response to the deaths of Aboriginal people in custody, confronted passersby in the heart of Melbourne’s arts precinct. Like many of his works, it combined Pop Art aesthetics with political urgency, asking not for permission, but for justice.

These artists are not working in isolation. They’re part of a broader network of curators, writers, activists, and institutions that have pushed for Indigenous-led narratives to take center stage. The Yalingwa Initiative, launched in 2017, is one such vehicle—funding Indigenous curators and artists to create major new work for exhibitions at ACCA and TarraWarra Museum of Art. It ensures that First Nations people are not just subjects of exhibitions, but their authors and architects.

Education has also played a major role in this resurgence. Institutions like RMIT, VCA, and Monash University have increasingly integrated Indigenous methodologies and voices into their visual arts programs, and emerging artists are being nurtured through residencies, mentorships, and collectives. Blak Dot Gallery in Coburg is one of Australia’s only Indigenous-run contemporary art spaces, fostering experimental and community-focused work by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists and other people of color.

Perhaps most importantly, contemporary Indigenous art in Melbourne is not confined to trauma or protest—though both are often central themes. It is also about joy, memory, sovereignty, innovation, and continuity. Artists are exploring the intersections of tech and tradition, of urban life and ancestral law. Whether through AR installations, wearable art, or ceremonial performance, First Nations artists are reminding the public—and the art world—that their cultures are not relics, but evolving systems of knowledge and creativity.

This resurgence also challenges the idea that decolonization is a metaphor. Many of these artists call for real material change: land back, treaty, truth-telling. They use art as a means of political intervention, but also as a vehicle for healing and celebration. When Reko Rennie writes “Always Was, Always Will Be” across a city wall, it’s not a slogan—it’s a reality, both spiritual and legal, that art makes visible.

In this sense, Indigenous art in Melbourne today is more than a genre or a category. It is a movement of reclamation, innovation, and resistance. It doesn’t ask to be included in the canon—it redefines what the canon is.

Institutional Pillars: NGV, ACCA, and Beyond

In Melbourne, art isn’t just something that happens in back rooms or bohemian studios. It’s institutional. It’s monumental. It’s a cornerstone of civic identity. While laneways and grassroots collectives have injected the city with energy and edge, it’s the major art institutions—the enduring pillars—that have given Melbourne its foundation as a true cultural capital. Their architecture looms large; their exhibitions draw millions; their collections are both mirrors and molders of the society they serve.

At the top of this institutional hierarchy is the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV)—not just Melbourne’s premier gallery, but Australia’s oldest and most-visited art museum. Founded in 1861 and housed today across two sites—NGV International on St Kilda Road and The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia at Federation Square—the NGV has long played a dual role: guardian of the classical canon, and host to contemporary experiment.

The NGV’s founding ambition was clear: to bring high culture to a fledgling colony. Its early acquisitions focused heavily on European painting and sculpture, building a collection that still boasts Old Masters, Impressionists, and a formidable decorative arts archive. But in recent decades, the NGV has undergone a strategic evolution, transforming from an “encyclopedic museum” to a globally competitive cultural engine.

Under the leadership of directors like Tony Ellwood, the NGV has pursued major contemporary exhibitions—think Basquiat x Warhol, Triennials, and fashion retrospectives from Dior to Alexander McQueen. These blockbuster shows have helped redefine what a public art museum can be: not a static shrine to the past, but a dynamic, public-facing cultural space that attracts locals, tourists, families, and critics alike.

Simultaneously, the NGV has taken significant strides to foreground Australian and Indigenous art, especially through its Ian Potter Centre. Located in the heart of Melbourne at Federation Square, this venue houses a dedicated collection of Australian works—historic, modern, and contemporary—within a context that encourages dialogue between past and present, between settler and First Nations perspectives.

While the NGV towers in size and scope, it is not alone in shaping Melbourne’s art scene. The Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in Southbank plays a complementary role—leaner, more experimental, and laser-focused on contemporary practices. Established in its current form in 2002 (but with roots dating to the 1980s), ACCA has become the city’s foremost platform for cutting-edge installation, performance, and conceptual art.

ACCA’s rust-colored façade is as distinctive as its curatorial voice. It doesn’t collect; it commissions. This means its exhibitions are often first-time, site-specific, and ambitious in scale. Artists like Patricia Piccinini, Mikala Dwyer, and Destiny Deacon have all presented major works here, and programs like Yalingwa, which foreground Indigenous curatorial leadership, have made ACCA an essential site for First Nations contemporary art.

Other key players in the institutional ecosystem include the Heide Museum of Modern Art, located in Bulleen, just outside central Melbourne. Heide’s history is legendary: it began as a private home to art patrons John and Sunday Reed, who hosted some of Australia’s most iconic modernists, including Sidney Nolan and Joy Hester. Today, Heide is a public museum, garden, and archive, preserving both its modernist heritage and supporting new work across three gallery spaces.

The Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP) in Fitzroy is another vital site, particularly for lens-based media. Since its founding in 1986, it has supported emerging and established artists working in photography, video, and digital forms. Its intimate, flexible spaces encourage risk-taking and deep engagement with visual culture.

Melbourne’s university galleries also deserve recognition. Institutions like RMIT Gallery, Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), and the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) galleries contribute significantly to the intellectual and experimental edge of Melbourne’s art scene. These venues act as bridges between academia and the broader public, often showcasing research-driven practices and interdisciplinary work.

In recent years, smaller and more agile institutions have gained visibility. Spaces like Gertrude Contemporary (now in Preston), West Space, and BLINDSIDE function as artist-run initiatives (ARIs)—critical sites for emerging artists, curators, and writers. These spaces often operate on shoestring budgets but deliver some of the city’s most provocative programming. They are laboratories for new ideas, grounded in community and artistic solidarity.

Melbourne’s institutional strength lies not in homogeneity, but in its ecosystemic diversity. Each venue—whether grand or humble, historic or insurgent—contributes to a complex cultural dialogue. There’s space here for the Renaissance and for Reko Rennie, for climate-focused VR installations and century-old oil portraits, for the subversive and the sublime.

And crucially, these institutions don’t exist in a vacuum. They are entangled with politics, funding structures, education, and public opinion. They face the pressures of relevance, equity, and sustainability. But it is precisely because of their adaptability—and their interplay with grassroots scenes—that Melbourne continues to thrive as a city where art is not just consumed, but debated, loved, challenged, and lived.

Art Education and Artist Communities

Beneath Melbourne’s galleries and institutions lies something more organic, more intimate, and arguably more essential: the vast and intricate web of education and artist communities that feed the city’s art scene. It’s not just the works on the walls that define Melbourne—it’s the people behind them: students learning to mix pigments, collectives meeting in converted warehouses, and mentors passing down both craft and rebellion. If the NGV is the city’s cultural flagship, then its art schools, studios, and communities are its nervous system—quietly animating everything else.

Art education in Melbourne has deep roots. The National Gallery School, founded in 1867, was Australia’s first formal art training institution. Housed initially within the NGV itself, the school quickly became a crucible for young talent. Its curriculum—rooted in the traditions of European academies—focused on drawing from life, perspective, and anatomy, establishing a rigorous technical foundation that shaped early movements like the Heidelberg School. Alumni such as Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Frederick McCubbin would go on to define Australian painting in the late 19th century.

In the 20th century, the school evolved into what is now the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), a cornerstone of the University of Melbourne and a breeding ground for experimentation across visual arts, theatre, dance, film, and music. VCA remains a vital part of the city’s creative engine, offering not only formal education but an environment that fosters interdisciplinary collaboration, critical theory, and a willingness to break rules.

Another key player is RMIT University, whose art programs have long emphasized innovation, industrial design, and contemporary practice. Located in the heart of the CBD, RMIT has become synonymous with cutting-edge visual arts and media, producing artists who are as comfortable in coding labs and fabrication studios as they are with brushes and canvases. The university’s engagement with public art, fashion, and architecture has made it an essential bridge between education and the broader urban fabric.

Alongside these major institutions are smaller but no less influential programs at places like Monash University (with its research-forward Monash University Museum of Art, or MUMA), Deakin, and La Trobe, each contributing to Melbourne’s diverse educational landscape. These schools aren’t just pipelines to galleries—they’re communities in their own right, fostering critique, collaboration, and lifelong networks among artists, curators, and writers.

Yet formal education is only half the story. Just as crucial are the city’s artist-run initiatives (ARIs) and grassroots collectives, which have served as alternative art schools, laboratories, and social spaces for decades. Venues like Gertrude Contemporary, West Space, BLINDSIDE, Seventh Gallery, and Bus Projects offer emerging artists opportunities to exhibit, curate, and engage with peers outside the commercial or institutional mainstream. These spaces operate with a DIY ethos, prioritizing experimentation and risk over polish and profit.

Melbourne’s inner north—suburbs like Fitzroy, Brunswick, and Collingwood—has long been the heartland of these communities. In post-industrial warehouses and terrace-house studios, artists share tools, ideas, meals, and critiques. Collectives form and reform, often driven by shared politics, aesthetics, or simply friendship. These micro-communities are where many of Melbourne’s most influential artists first find their voice, unmediated by the expectations of galleries or markets.

The city’s artist communities are also deeply political. Artist-run spaces often intersect with activist movements—housing justice, climate action, anti-racism—and function as spaces of resistance and solidarity. The Rise: Refugee Advocacy Collective, Indigenous-run projects like Blak Dot Gallery, and LGBTQ+ initiatives have all used art as a platform for community-building and visibility.

Residency programs also play a key role. The Gertrude Studio Program, for instance, offers two-year residencies to a select group of emerging artists, providing not just space but mentorship, exposure, and professional development. Similarly, Collingwood Yards, a new creative precinct in the former Collingwood TAFE site, has become a hub for artists, musicians, designers, and arts organizations, embodying Melbourne’s commitment to keeping the city’s creative heart accessible and collaborative.

Crucially, Melbourne’s artist communities aren’t static—they’re adaptive. Rising rents and gentrification have pushed many studios out of the inner city, leading to new pockets of creativity in suburbs like Footscray, Coburg, and Preston. These shifts mirror broader socio-economic trends, but they also reflect the resilience and mobility of the artist community: if one door closes, a garage becomes a gallery, a kitchen becomes a darkroom.

The interplay between formal education and informal community is one of Melbourne’s greatest cultural assets. Artists who graduate from the VCA might show their first works at West Space. A designer from RMIT might team up with a sculptor from Brunswick to start a collective. These interwoven paths generate not just careers, but a culture of mutual support and shared growth that is rare in major urban centers.

In short, Melbourne is not an art city because of its institutions alone. It is an art city because it nurtures its artists, through education, community, and an unspoken promise: that creativity matters, and that there will always be a space—somewhere—to make, to show, and to be seen.

Biennales, Festivals, and Global Engagement

Melbourne is a city that doesn’t just produce art—it broadcasts it. Over the past few decades, the city has evolved into an international stage where ideas, aesthetics, and identities are exchanged, debated, and performed at scale. Through a diverse ecosystem of biennales, triennials, art fairs, and festivals, Melbourne has forged strong connections with the global art world while asserting its own distinctive voice. These events are more than showcases—they are cultural infrastructures that reflect and shape how Melbourne sees itself and how the world sees Melbourne.

At the forefront of this global outreach is the NGV Triennial, first launched in 2017 and now firmly established as one of the most ambitious recurring contemporary art exhibitions in the Southern Hemisphere. Designed to bring international artists into dialogue with Australian practitioners, the Triennial occupies every inch of NGV International and often spills into the surrounding city. It’s a spectacle of form, color, and concept—featuring everything from AI-driven installations and bio-art to large-scale sculpture, wearable tech, and immersive environments.

But the NGV Triennial isn’t just about visual impact. It’s also curatorial—designed around urgent global themes: power, identity, ecology, and technology. It positions Melbourne not as a passive receiver of trends, but as a contributor to global artistic discourse. Previous editions have featured major figures like JR, Paola Pivi, and Refik Anadol alongside Australian powerhouses like Patricia Piccinini and Brook Andrew, creating a dynamic interchange between the local and the international.

Running in parallel with these institutional blockbusters are grassroots and experimental festivals that give space to voices from the edges. The Next Wave Festival, founded in 1984, has long championed early-career artists across disciplines. Known for its risk-taking, political charge, and cross-cultural inclusivity, Next Wave commissions new work that often defies easy categorization—spanning visual arts, performance, sound, and digital media. For many artists, it’s a launching pad. For audiences, it’s a glimpse into the future of art.

Similarly, the Melbourne Art Fair, relaunched in 2018 after a short hiatus, has reasserted itself as one of the premier commercial art fairs in the Asia-Pacific region. It gathers leading galleries, collectors, curators, and artists under one roof, facilitating not just sales but conversations and collaborations that ripple across the industry. The fair has increasingly foregrounded First Nations and Asia-Pacific perspectives, aligning with broader moves to decolonize and diversify the art market.

More grassroots and multidisciplinary in nature is the Melbourne Fringe Festival, which embraces a radically open definition of art. Visual installations, body art, street interventions, and live painting coexist with comedy, cabaret, and experimental theatre. For visual artists, Fringe offers a space outside of curatorial hierarchies—where anyone can show anything, and where art is a process as much as a product.

These festivals are part of a larger effort to position Melbourne as a creative capital on the world stage. Government bodies like Creative Victoria and the Australia Council for the Arts actively fund international touring, residencies, and exchange programs. Local artists frequently exhibit at the Venice Biennale, Documenta, and Asia-Pacific Triennial, while Melbourne regularly hosts international curators, scholars, and collectors.

Cultural diplomacy has also become a strategy. Through sister-city relationships (notably with Milan, Osaka, and Thessaloniki), Melbourne exports exhibitions, hosts exchange programs, and facilitates cross-border artistic partnerships. Institutions like the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) contribute to this international profile, curating film and digital media programs that speak to global audiences while remaining rooted in local stories.

Yet, global engagement isn’t just about prestige or market expansion—it’s about building cultural dialogue, and often, accountability. Many of these events have become platforms for confronting shared global challenges: climate change, migration, colonialism, digital surveillance, and inequality. Artists use Melbourne’s stages to offer not just works, but provocations—asking viewers to think, to respond, to act.

Importantly, the presence of international art in Melbourne has also sharpened local practice. It creates a pressure—sometimes inspiring, sometimes contentious—for Australian artists to position themselves within global movements. But it also offers opportunity: to learn, to adapt, and to assert. Melbourne’s artists are increasingly cosmopolitan—not just in influence, but in intent.

In the 21st century, no art city can be insular. And Melbourne is anything but. It is a city that welcomes biennales and banners, residencies and retrospectives, critique and carnival. It builds pavilions and tears them down. It exhibits the world and, in doing so, offers itself to the world. And through these acts of exchange, it continually renews its place on the global map—not as an echo of elsewhere, but as a voice uniquely its own.

Art and Activism: Political Voices in Melbourne Art

In Melbourne, art doesn’t always whisper—it often shouts. From the laneways of Fitzroy to the walls of the NGV, from guerilla wheatpastes to gallery interventions, Melbourne has long been a crucible for art as activism. Its artists have refused the comfort of neutrality, using their work to contest injustice, demand change, and reimagine society. In this city, aesthetics and ethics are frequently entwined—making political art not a subgenre, but a central, ongoing tradition.

The roots of Melbourne’s activist art scene go deep. In the 1970s and ’80s, feminist artists like Jill Orr, Bonita Ely, and Vivienne Binns emerged with bold performance works that challenged patriarchal structures and exposed the limitations of the male-dominated art world. These performances often took place outside the gallery—on beaches, in public squares, or through ephemeral installations—blurring the lines between protest, theatre, and ritual. Their message was clear: the body is political, and the personal is public.

Parallel to this, Indigenous artists and activists were pushing back against Australia’s colonial amnesia. Melbourne played a key role in the rise of urban Aboriginal art—art that didn’t come from desert dot painting traditions, but from city-based collectives responding to systemic racism, land rights struggles, and state violence. The Aboriginal Advancement League, Koorie Heritage Trust, and later galleries like Blak Dot and KHT’s Federation Square space became focal points for visual resistance.

Artists such as Destiny Deacon, with her darkly satirical photographs, and Richard Bell, whose text-based works pull no punches, helped redefine what political art could be in Australia—biting, beautiful, and deeply uncomfortable. Their work didn’t just ask to be seen—it demanded to be reckoned with.

The 1990s and 2000s brought new flashpoints. The rise of neoliberalism, the Tampa refugee crisis, the Iraq War, and the NT Intervention all catalyzed Melbourne artists into direct action. Protest art flourished, often blending traditional mediums with new tactics—guerrilla projections, banner drops, zines, social media campaigns, and ephemeral installations. Collectives like Artillery, Revolutionary Art Movement, and Melbourne Artists for Asylum Seekers emerged, linking art-making with solidarity networks and activist organizing.

Perhaps one of the most visible manifestations of political art in the city has been the street. Melbourne’s graffiti and stencil culture became a global benchmark not just for style but for subversion. Artists like Ha-Ha (Regan Tamanui) used stenciling to depict Indigenous heroes like Ned Kelly reimagined as resistance icons. Others turned walls into rolling commentary on gentrification, surveillance, climate denial, and war. The laneways became a living manifesto, constantly overwritten, but never silenced.

In recent years, art-activism has gone digital and spatial. Projection art has emerged as a potent tool—images cast onto buildings, monuments, or natural landmarks, reclaiming public space in luminous bursts. Artists like Vicki Couzens and Paul Yore have used immersive installations to critique colonialism, queerphobia, and environmental destruction while celebrating identity and resilience.

Public institutions have also been sites of activism. In 2019, the NGV faced protests over its security contract with Wilson Security, a company involved in the operation of offshore detention centers. Artists, including those featured in the NGV Triennial, staged walkouts, interventions, and boycotts. These acts sparked national debates about the ethics of cultural institutions, complicity, and the responsibilities of artists in neoliberal art economies.

Another key battleground has been public monuments and memorials. Inspired by global movements to decolonize public space, Melbourne activists and artists have called for the removal or reinterpretation of statues celebrating colonizers like Captain Cook or Queen Victoria. Counter-monuments—temporary, performative, or symbolic—have emerged in their place, often created collaboratively by First Nations artists and community groups.

Melbourne’s activist art is also fiercely intersectional. It addresses not just one axis of oppression but multiple—race, class, gender, sexuality, disability, and climate. Queer artists have long used visual language to claim space and critique heteronormative narratives, particularly through performative and body-based work. Environmental artists, responding to bushfires, floods, and climate anxiety, create works that mourn loss while calling for urgent change—often with materials and methods that are themselves sustainable or site-specific.

Importantly, art activism in Melbourne often doesn’t aim for permanence—it aims for impact. It disrupts, unsettles, prompts dialogue. It might last a night, a week, a season, but its echoes remain. The best political art doesn’t tell you what to think—it forces you to feel, to confront your complicity, and to imagine something different.

In a city like Melbourne, where civic life and cultural life are deeply entangled, art is not a spectator sport. It’s a method of inquiry, a tool of resistance, a banner in a march, a mural on a wall, a flicker in a protestor’s eye. And through this constant interplay between art and action, Melbourne’s visual culture remains not just relevant, but urgent.

Collecting and Patronage: The Role of the Public and Private Sector

In any city, art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It flourishes—or withers—within systems of support and selection, shaped as much by money as by imagination. In Melbourne, a vibrant network of public institutions, private collectors, corporate sponsors, and philanthropic foundations has sustained the city’s art ecosystem for over a century. These patrons may not always be visible in the frame, but they are often the ones holding it up.

Melbourne’s tradition of art philanthropy began in earnest during the city’s late 19th-century boom. As wealth from the gold rush transformed a colonial outpost into a cosmopolitan city, affluent individuals began investing not only in real estate and infrastructure but in culture. Art collecting became a marker of status, sophistication, and civic virtue.

The most consequential figure in this tradition is undoubtedly Alfred Felton, a pharmaceutical entrepreneur whose 1904 bequest to the National Gallery of Victoria changed the trajectory of Australian art forever. His endowment—worth millions in today’s dollars—enabled the NGV to purchase masterpieces from Europe and establish one of the Southern Hemisphere’s most formidable collections. To this day, the Felton Bequest continues to fund acquisitions, including works by Indigenous and contemporary artists, ensuring that Melbourne’s public collection evolves with the times.

But Felton was only the beginning. Throughout the 20th century, collecting in Melbourne expanded beyond public institutions. Wealthy individuals like Elisabeth Murdoch, Carrillo Gantner, and John Kaldor became major patrons, supporting both traditional art forms and avant-garde experimentation. Some donated works to museums, others established their own foundations, and a few—like Sunday and John Reed—created entire institutions, such as the Heide Museum of Modern Art, out of their homes.

In the contemporary era, corporate collections have also played a significant role. Law firms, banks, universities, and developers began acquiring Australian art for their foyers and boardrooms, commissioning site-specific works and helping sustain artists financially. While not always publicly visible, these corporate collections often shape market trends and raise an artist’s profile. Companies like Macquarie Group and BHP have sponsored major exhibitions, while partnerships between the NGV and brands like Hermès or Bvlgari highlight the increasingly blurred lines between art and commerce.

Government support has been another essential pillar. At the federal level, the Australia Council for the Arts offers grants for individual artists, collectives, and touring exhibitions. Locally, Creative Victoria funds everything from artist-run spaces to international festivals. The City of Melbourne itself has an active arts strategy, commissioning public art, offering studio residencies, and maintaining a public art collection that spans everything from bronze sculptures to contemporary digital installations.

Yet public funding comes with its own pressures: budget cuts, political interference, cultural gatekeeping. Debates often rage over what gets funded and why. Should public money support controversial or experimental work? What constitutes community benefit? These questions flare up regularly, especially when art intersects with politics—as seen in past controversies over works critiquing Australia’s refugee policy, climate inaction, or colonial legacies.

One area of increasing focus is Indigenous art patronage. After decades of marginalization, many institutions and collectors are now prioritizing First Nations works—not just as a corrective gesture, but as a recognition of their centrality to Australia’s cultural story. The NGV, for example, has dedicated curators and funding streams for Indigenous art, while private collections like that of Carrillo and Ziyin Gantner have helped promote Southeast Australian Aboriginal artists, whose work is often underrepresented in national collections.

At the grassroots level, crowdfunding, collectives, and co-operative models are also gaining traction. Platforms like Pozible have enabled artists to bypass traditional gatekeepers and appeal directly to audiences. Community-run galleries often pool resources or apply for group funding, creating models of support that prioritize equity and sustainability over profit.

Melbourne’s art market, too, plays a shaping role. Commercial galleries like Tolarno, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sutton Gallery, and Station help develop the careers of contemporary artists while connecting them to collectors, critics, and international curators. While these galleries operate with commercial aims, many are also sites of rigorous curatorial practice, commissioning new works and providing crucial early support.

But the power dynamics of collecting remain contested. Who gets to build the canon? Who decides what is “important” enough to preserve, display, or fund? These questions have taken on new urgency in an era of decolonization, climate crisis, and cultural equity. Institutions are being asked not just to collect more diversely, but to rethink the ethics of collecting altogether.

Some museums are reassessing the provenance of their holdings, particularly items acquired during colonial periods. Others are returning objects to communities or engaging in long-term consultation processes. In this climate, the act of collecting becomes a form of cultural diplomacy or justice, rather than simply connoisseurship.

What’s clear is that collecting and patronage—long viewed as backroom affairs—are now active parts of the public conversation. And in Melbourne, where art is so closely tied to civic identity, these conversations matter. Whether it’s a philanthropist funding a major acquisition, a city council commissioning a mural, or a collective pooling resources for an artist-run space, each act of support is also an act of shaping what kind of city Melbourne is, and what kind of stories it chooses to tell.

Digital Futures: New Media and the Next Wave

If Melbourne’s art history is a story of reinvention, its future is already unfolding—in pixels, algorithms, networks, and screens. As the 21st century progresses, the city’s artists are no longer confined to the gallery wall or studio space. Instead, they’re coding, streaming, animating, and augmenting, creating works that move across dimensions, disciplines, and devices. The question isn’t just “What is art?” but “Where is it, who makes it, and how do we experience it?”

Melbourne’s embrace of new media art has been both rapid and reflective. It didn’t simply leap into technology for technology’s sake—it adapted, thoughtfully, to new tools while holding onto its deep traditions of experimentation, critique, and conceptual depth. The result is a city at the forefront of digital practice, where visual artists often function as software developers, designers, theorists, and storytellers.

The most prominent institutional platform for this evolution has been ACMI (the Australian Centre for the Moving Image), based in Federation Square. Originally launched as a film museum, ACMI has since expanded into one of the world’s leading digital culture hubs. Its exhibitions explore everything from video art and interactive installations to gaming, data visualizations, and immersive storytelling. Recent shows have examined the politics of AI, the aesthetics of code, and the emotional weight of digital life.

ACMI’s renewal in 2021—an ambitious architectural and curatorial overhaul—positioned it as a truly hybrid venue. It offers both physical exhibitions and a rich online platform, ensuring that digital art isn’t just displayed but lived and navigated across multiple media. It’s a model that other institutions in Melbourne are beginning to emulate, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated interest in online exhibitions, livestreamed performances, and virtual reality spaces.

Melbourne’s art schools have played a major role in fostering this shift. At RMIT, digital media is not an add-on—it’s a core part of the curriculum. Students work with VR, AR, generative design, and interactive systems, often blurring the lines between fine art, tech, and industrial design. VCA and Monash University, too, have embraced interdisciplinary labs where artists collaborate with engineers, scientists, and coders.

This future-forward ethos is visible in the work of artists like Stelarc, whose robotic performances and bio-art pieces have pushed the boundaries of the body itself; Troy Innocent, whose urban AR games transform city streets into interactive playgrounds; and Lucreccia Quintanilla, who combines sound, sculpture, and post-internet aesthetics to explore diasporic identity and techno-culture.

NFTs and blockchain art have also made their mark in Melbourne—though with a healthy dose of skepticism and critique. While some artists have embraced the opportunities of decentralized platforms, others question their environmental impact and speculative economics. What’s striking is how Melbourne’s art scene doesn’t adopt trends uncritically—it interrogates them. What does it mean to “own” digital art? Who benefits? What is lost when art becomes tokenized?

Alongside these digital shifts is a renewed interest in interactivity, co-creation, and immersive experience. Festivals like Next Wave, Melbourne Fringe, and Pause Fest (which focuses on tech and creativity) now regularly feature works that use sensors, augmented environments, AI, or audience input as core components. These projects ask viewers to become participants, collaborators in meaning-making.