Gujarat, the western jewel of the Indian subcontinent, has long been a crucible of cultural confluence, trade, religion, and resilience. To speak of Gujarati art is to evoke a palimpsest of visual traditions layered across millennia—from the delicate linework of Jain manuscripts to the riotous color of Bandhani textiles, from ancient temple carvings to the canvases of contemporary painters. Art in Gujarat is not a monolithic entity; rather, it’s a vibrant spectrum of expression that has evolved with history, geography, and society. It is shaped as much by the arid salt flats of Kutch as it is by the rich mercantile legacies of cities like Ahmedabad and Surat.

What distinguishes Gujarati art is its rhythmic oscillation between refinement and rusticity, the sacred and the everyday, the local and the cosmopolitan. Throughout its long and complex history, Gujarat has been both a center of indigenous innovation and a porous frontier open to external influence. Its strategic coastal position connected it to ancient Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, East Africa, and later, European empires. This maritime legacy left its imprint not only on trade and architecture but also on the artistic imagination.

Yet, Gujarati art is not merely the sum of its interactions—it is animated by a profound sense of place and community. Art here often arises not from solitary genius, but from collective hands and inherited rituals. Whether it is the hand-painted clay walls of a tribal village or the intricate weaving of a double ikat Patola sari, the emphasis is on craftsmanship imbued with meaning. Artistic practices are often closely tied to ritual, season, and belief, forming an intimate dialogue between people and the divine, between labor and celebration.

A Crossroads of Civilizations

The region’s deep time-line begins with the Indus Valley Civilization, whose urban centers at Dholavira and Lothal speak to a sophisticated material culture: terracotta figurines, etched beads, seals bearing animal motifs. These were not simply utilitarian objects—they were the aesthetic expressions of a society deeply invested in order, symbolism, and perhaps even metaphysical speculation. Fast forward to the 11th and 12th centuries, and Gujarat becomes a heartland of Jain cultural patronage, spawning not only temples of dizzying complexity but also a manuscript tradition of exquisite color and calligraphy.

The state’s Islamic period brought new forms and aesthetics. Under the Sultanate of Gujarat, art took on new architectural and decorative idioms, blending Indo-Islamic styles in everything from tombs to mosques to palatial carvings. The later arrival of the British brought new disruptions and possibilities, reorienting art education, shifting patronage structures, and introducing new materials and technologies. Yet, through it all, Gujarat maintained an artistic identity that was adaptive yet rooted—an identity still discernible in the 21st century.

Art as Embodied Experience

In Gujarat, the experience of art is often multisensory and participatory. Art is danced during Garba, chanted in the padyavalis of Bhakti poets, worn on the body through embroidery, woven into doorways with torans, and even smeared onto the ground in geometric Rangoli patterns. This is a world where aesthetic and spiritual expression are inseparable. For many communities, art is a form of offering, remembrance, and resistance—an interface with ancestry and aspiration alike.

This deeply embodied nature of Gujarati art challenges the modern Western notion of art as object-centric, gallery-bound, and elite. Here, art lives in the body and the community. It is performed, shared, and sustained through oral traditions and intergenerational transmission. This ethos survives even as artists today experiment with new forms, digital technologies, and global platforms.

Baroda and the Rise of the Modern

One of the most striking developments in post-independence India was the rise of Baroda (Vadodara) as a major center of modern art education and practice. The Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University, founded in 1950, became a magnet for young talent from across the country. Under influential figures like K.G. Subramanyan, Gulammohammed Sheikh, and Jyoti Bhatt, Baroda fostered a unique vision of modern Indian art—rooted in Indian traditions but unafraid to engage with international avant-garde ideas. It was here that Gujarat became not only a site of folk and classical continuity but also of radical experimentation and critical engagement.

Baroda’s artists reinterpreted Gujarat’s folk motifs, tantric symbols, and narrative traditions in ways that were both homage and innovation. Their work interrogated the very notion of Indian identity, using Gujarat’s visual lexicon as both anchor and launchpad. This phase of Gujarati art expanded its reach beyond religious and craft-based boundaries and entered the sphere of conceptual and political discourse.

Today’s Gujarat: Continuities and Reimaginings

In contemporary Gujarat, one finds art in bustling urban centers and remote tribal settlements alike. Contemporary artists such as Hema Upadhyay, Atul Dodiya, and Nilima Sheikh—while not always residing in Gujarat—carry forward the region’s aesthetics and concerns in their work. Meanwhile, rural and folk artists continue to innovate within tradition, creating works that blur the lines between “high” art and “craft.”

Organizations like the Kala Raksha Trust, Khamir, and the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad are fostering new models of collaboration between traditional artisans and contemporary designers. These cross-pollinations are not without tension, but they represent the latest chapter in Gujarat’s long history of artistic negotiation between past and future.

A Tradition That Breathes

To write about Gujarati art is to resist the temptation of closure. It is a living tradition, evolving in conversation with the forces of migration, commerce, faith, and modernity. Its expressions are as diverse as its dialects and as layered as its cities. From the salt-encrusted villages of Kutch to the galleries of New York, Gujarati art continues to challenge, enchant, and evolve.

In the chapters that follow, we will journey through these many threads—ancient, devotional, tribal, colonial, modern—tracing how Gujarat’s art has remained not only relevant but vital. Whether you’re a scholar, artist, or curious observer, the story of Gujarati art is ultimately a story about how people give form to meaning, beauty to belief, and permanence to the ephemeral.

Ancient Origins: Art in the Harappan and Early Historic Period

Long before Gujarat came to be known for its opulent temples and richly dyed textiles, its soil was home to one of the world’s oldest urban civilizations—the Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization. Gujarat formed its southernmost frontier, with major sites like Dholavira, Lothal, Surkotada, and Rangpur emerging as key centers of trade, culture, and technology. This period, spanning roughly 2600 to 1900 BCE, reveals a deep-rooted visual and material culture that laid the foundation for Gujarat’s later artistic achievements.

Although the Harappans did not leave behind monumental sculpture or painting in the way classical Indian civilizations would, their aesthetic sensibility is unmistakable. It speaks in the subtle elegance of a ceramic design, the geometry of a bead necklace, the careful stylization of an animal on a seal. Harappan art, especially as seen in Gujarat, was about order, symbolism, and abstraction, often with a mysterious, coded restraint that still fascinates archaeologists and art historians alike.

Dholavira: Geometry, Urbanism, and Symbol

One of the most striking archaeological finds in Gujarat is Dholavira, located in the Rann of Kutch. Discovered in the 1960s and excavated extensively since the 1990s, Dholavira stands out for its sophisticated urban planning—multi-zoned architecture, water reservoirs, gateways, and a distinct acropolis-lower town division.

But beyond its engineering marvels, Dholavira provides an early glimpse into the visual order and spatial aesthetics that would characterize Gujarati art for centuries. The city’s layout suggests a civilization deeply concerned with symmetry, directionality, and environmental integration—principles that echo in later temple architecture. Perhaps most intriguingly, Dholavira yielded a signboard containing ten large Indus script symbols, which may represent one of the earliest known public signages in the world—an object as artistic as it was functional.

Among artifacts recovered here are delicately crafted terracotta figurines, etched carnelian beads, and bangles made of conch shell, suggesting a society that valued personal adornment and symbolic craft.

Lothal: Port, Trade, and Craft

If Dholavira was a city of structure, Lothal was one of exchange. Located southeast of modern Ahmedabad, Lothal’s archaeological fame rests on its dockyard—arguably the earliest known in the world. This port connected Gujarat to Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf, enabling a flow of not just goods but artistic influences.

Excavations at Lothal revealed a rich collection of seals, beads, faience objects, pottery, and metallurgy. The seals, often bearing animal motifs like unicorns, bulls, and elephants, were not merely bureaucratic tools but stylized miniatures of representational art. Their minimalist yet evocative lines suggest a highly developed symbolic language. Some even depict composite creatures or what might be proto-mythical figures, hinting at early narrative traditions.

Pottery found at Lothal is equally illuminating. Painted wares feature geometric motifs, stylized animals, and repetitive patterns, showing a preference for harmony and repetition. The aesthetic, while largely abstract, demonstrates a keen eye for rhythm and balance—qualities that would become central to Gujarati textile design in later centuries.

Material Culture and the Proto-Artisan

While the Harappan world lacked the monumental sculptures of Egypt or Mesopotamia, its artisans left behind subtle signatures in everyday objects. In Gujarat, especially, the abundance of craft-based artifacts points to a society where art and utility were deeply entwined. Shell-working, bead-making, and metallurgy were not simply economic activities; they were forms of material intelligence and visual culture.

Beads—especially those of carnelian—are of particular note. Manufactured through a laborious process involving drilling, heat-treating, and polishing, these beads were more than decoration. They carried symbolic meaning, perhaps marking status, identity, or trade networks. Lothal’s bead factory is a testament to this proto-artisan economy.

Terracotta figurines—mostly animals, female forms, and carts—give further insight into belief and play. The female figures may represent fertility deities or protectors, while the animals range from stylized bulls to birds, all modeled with a balance of abstraction and realism. These were perhaps toys, votive offerings, or ritual items, revealing an aesthetic deeply rooted in the tactile and domestic.

Early Historic Period: Transition and Continuity

With the decline of the Harappan civilization around 1900 BCE, Gujarat entered a period of cultural transformation. Yet, art did not vanish—it evolved, integrating new influences from Vedic, Jain, and Buddhist currents as new kingdoms rose across the subcontinent.

Sites like Devnimori in northern Gujarat—dated to around the 3rd to 4th centuries CE—yield Buddhist relics, including beautifully carved Bodhisattva heads and terracotta plaques. This transition marks the beginning of Gujarat’s entry into mainstream Indian religious art, with stone carving, image worship, and architectural elaboration beginning to emerge more clearly.

This period also saw the emergence of early Jain communities in Gujarat, who would become some of the most significant patrons of art and architecture in the region. Their influence would bloom in later centuries, but even here, in this early stage, we see a movement toward narrative representation, cosmological imagery, and sacred geometry—all of which link back, in subtle ways, to the ordered aesthetic of the Harappan worldview.

A Legacy in Fragments

Much of Gujarat’s ancient artistic history comes to us in fragments—shards of pottery, worn figurines, undeciphered seals. Yet these fragments are potent. They remind us that even the earliest societies in this region sought not only to build and survive, but to express, decorate, and symbolize.

These early forms of expression laid a foundation that Gujarat would build upon for centuries to come. The balance of utility and symbolism, the emphasis on craft, the preference for stylized abstraction over narrative realism—all these seeds were planted in the Indus Valley era and carried forward into Gujarat’s later religious, folk, and textile arts.

In tracing the contours of Harappan Gujarat, we find not a lost world, but a visual vocabulary in formation—one that would echo in stone carvings, manuscript illuminations, and textile patterns for thousands of years. Gujarat’s artistic journey does not begin with dynasties or temples, but with clay, shell, and fire—shaped by anonymous hands that saw beauty in balance and form in function.

Medieval Splendor: Jain Manuscript Illustration and Temple Art

Between the 11th and 15th centuries, Gujarat emerged as one of India’s most powerful and artistically prolific regions. This period coincided with the rise of the Solanki dynasty, the flourishing of Jainism, and the consolidation of Gujarat’s merchant class—forces that together created a rich ecosystem for religious and visual expression. In this age of piety and patronage, art in Gujarat reached new levels of intricacy, spiritual symbolism, and luminous color.

The Jains, who had a significant presence in Gujarat by this time, became some of the most influential patrons of art, not only funding monumental temple complexes but also sponsoring a remarkable tradition of manuscript illustration. These painted texts, produced primarily in the region between Ahmedabad, Patan, and Cambay, stand as some of the most beautiful examples of pre-modern Indian book art. Alongside this, temple architecture—especially during the Solanki period—developed a distinctive style of ornate carving and sacred geometry that continues to awe visitors today.

Together, these artistic forms created a dual visual canon: one static, monumental, and architectural; the other mobile, intimate, and textual. Both served the same spiritual purpose—to visualize the cosmic order, to honor the Tirthankaras, and to guide the devotee toward liberation.

The Jain Manuscript Tradition: Paper as Sacred Space

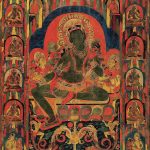

At the heart of Gujarat’s medieval painting lies the Kalpasutra, a canonical Jain text chronicling the lives of the Tirthankaras, particularly Mahavira. From the 12th century onwards, copies of this text began to be lavishly illustrated as acts of devotion and display. These manuscripts were typically written in Prakrit or Sanskrit, using delicate Devanagari or Jain Nagari scripts on palm leaf, and later, paper—a material that Gujarat helped pioneer in India.

What makes these manuscripts extraordinary is not merely their content, but their form: miniature paintings rendered in bold colors—especially reds, blues, and gold—set within tight, rectangular frames. The images often occupy the margins, sometimes squeezed between lines of text or interspersed as full-page illustrations. Yet, far from being decorative flourishes, these paintings are deeply didactic and symbolic.

Artists adhered to a highly stylized visual grammar: large, almond-shaped eyes; rigid, frontal poses; decorative elements over naturalistic detail. Backgrounds were frequently flat and abstract, often rendered in pure red or blue fields, giving the figures an almost icon-like presence. This wasn’t a failure of realism—it was a conscious aesthetic rooted in spiritual clarity. The goal was not to mimic the physical world, but to evoke the eternal truths of Jain philosophy: non-violence, asceticism, and cosmic order.

Notably, these manuscripts often contain elaborate colophons—notes that document the patron’s name, date, and occasion of commissioning. This practice underscores how tightly religion, commerce, and art were intertwined. Wealthy Jain merchants commissioned these illustrated texts as acts of spiritual merit, especially during festivals like Paryushana, and donated them to temples and libraries known as Bhandars.

Centers of Production: Patan, Cambay, Ahmedabad

The cities of Patan and Cambay (Khambhat) became major hubs of manuscript production. Patan, once the capital under the Solankis, was famed for its temple complexes and vibrant artisan communities. Scribes, painters, and binders worked in tandem, sometimes in family guilds, producing manuscripts not just for local temples but for clients across India.

The transition from palm leaf to paper around the 14th century revolutionized the scale and detail of manuscript art. Paper allowed for finer brushwork, more saturated pigments, and increased durability. Techniques such as gold leaf application, lacquering, and burnishing became more refined, resulting in manuscripts that were both spiritual texts and objects of luxurious beauty.

Interestingly, the aesthetic of Jain manuscript painting also influenced, and was influenced by, Western Indian painting more broadly. Its distinctive features—elongated eyes, frontal figures, and vivid palettes—would echo in Rajput miniatures and even in later Pahari schools, creating a pan-regional idiom rooted in Gujarat.

Solanki Temple Architecture: Sacred Stone

While manuscripts offered private, portable beauty, the temples of this period projected a public, monumental splendor. The Solanki dynasty (also known as the Chaulukyas), which ruled from the 10th to 13th centuries, presided over a golden age of temple construction in Gujarat. These temples combined technical mastery with symbolic precision, resulting in some of the finest examples of Indian temple architecture.

Foremost among them is the Modhera Sun Temple, built in the 11th century by King Bhima I. Dedicated to Surya, the sun god, the temple exemplifies Solanki artistry: it stands on a high plinth, features a pillared assembly hall (mandapa), and is preceded by a stepped tank known as the Surya Kund. The structure is a marvel of symmetry, celestial alignment, and sculptural detail. Every surface is covered in carvings—gods, dancers, musicians, animals, and mythical beings—rendered with astonishing delicacy.

Elsewhere, temples like the Rani ki Vav (Queen’s Stepwell) at Patan blend architectural ingenuity with narrative sculpture. This subterranean marvel, commissioned by Queen Udayamati, uses descending tiers and sculpted walls to create a sacred space that is both functional (as a water reservoir) and devotional. Its reliefs depict avatars of Vishnu, female guardians, and cosmic forms, echoing the ornate complexity of Jain visual logic.

The Solanki style is marked by shikhara towers, intricately carved toranas (gateways), and a penchant for filigree-like stonework. Later temple builders in Rajasthan and even South India would draw upon this vocabulary, but it was in Gujarat that this style first reached its full flowering.

Crossroads of Influence

Though primarily Hindu and Jain, Gujarat during this period was far from isolated. Trade routes connecting it to Persia, Arabia, and Africa brought new ideas, materials, and aesthetics. Islamic influence, though more dominant in later centuries, began to subtly permeate temple ornamentation and manuscript borders. Some scholars even argue for the exchange of geometric design principles between Jain manuscript painters and Islamic calligraphers.

Gujarat’s location at the intersection of inland trade routes and maritime networks made it a cultural crucible. The flourishing art of this period reflects that cosmopolitanism—at once rooted in indigenous belief and open to outside form.

Legacy and Survival

What survives from this golden period is both spectacular and fragmentary. Many Jain manuscripts were lost to time, fire, or colonial dispersion. Yet hundreds are preserved in temple libraries, particularly in places like Jaisalmer, Patan, and Palitana, where Bhandars remain active repositories of knowledge.

Temples, too, have withstood invasions and weather, though many were damaged or reappropriated in later periods. What remains, however, continues to draw pilgrims, scholars, and artists alike. In contemporary Gujarat, some artisan families still trace their lineage to medieval scribes and stone carvers, keeping traditions alive through temple conservation and artistic revival.

In the Jain communities of Gujarat and the diaspora, manuscript facsimiles are still commissioned for ritual use—proving that this tradition, while historical, remains a living thread in the fabric of Gujarati visual culture.

The Craft of Devotion: Temple Architecture and Sculpture

In Gujarat, art has always been inseparable from devotion. Nowhere is this more powerfully evident than in its temple architecture—a centuries-spanning tradition that transforms stone into both sanctuary and spectacle. From sun-drenched riverbanks to windswept hillsides, Gujarat’s sacred landscape is marked by a remarkable constellation of temples, each an embodiment of ritual, cosmology, and aesthetics.

The temples of Gujarat are not just places of worship; they are visual texts, carved in stone, narrating stories of gods and mortals, of ethical ideals and cosmic order. Their walls breathe with apsaras and yakshas, warriors and saints, flora and fauna—every inch a surface for the sacred. These structures exemplify an integrated art form, where architecture, sculpture, geometry, and symbolic thinking coalesce.

This section will trace the evolution of temple architecture in Gujarat from the Solanki period through the Sultanate era, and into modern times, with special attention to form, ornamentation, and the shifting meanings of sacred space.

Solanki Temples: Architectural Precision, Sculptural Ecstasy

As we explored earlier, the Solanki (Chaulukya) dynasty was the architectural patron par excellence. The temples they sponsored—between the 10th and 13th centuries—represent a peak in Gujarat’s temple building, synthesizing earlier forms from the Maitraka and Gurjara-Pratihara traditions with new ideas in iconography, layout, and spatial harmony.

A hallmark of Solanki architecture is the Maru-Gurjara style, also referred to as the “Western Indian temple style.” This school is marked by:

- Shikharas (temple towers) with a clustered, multi-spired appearance.

- Highly ornate mandapas (pillared halls) with sculpted ceilings.

- Intricate toranas (gateway arches) adorned with celestial and mythological motifs.

- A preference for interior sanctity and external profusion—inner sanctums are often simple, while exteriors are lavishly carved.

Temples such as the Sun Temple at Modhera and Rani ki Vav showcase not only technical virtuosity but also philosophical depth. The Sun Temple’s orientation with solar movements, for example, reflects a cosmological awareness where architecture becomes an astronomical instrument. Its garbhagriha (sanctum) was designed so that the rising sun would illuminate the deity’s image—an act of divine revelation enacted in stone.

The sculptural programs of these temples are encyclopedic. The outer walls are often divided into horizontal bands, each containing dozens of figurines: deities from the Hindu pantheon, scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, dancers frozen in elaborate poses, animals real and mythical. These are not decorative afterthoughts; they form a narrative logic that guides the devotee’s movement and contemplation.

Sculptors working under Solanki patronage developed a distinctive style—marked by fluid motion, sensuous detail, and symbolic gestures (mudras). Gods are depicted not merely in human form, but as expressions of cosmic principles, with visual clues encoded into jewelry, posture, and vehicle (vahana). Even the flora—lotuses, vines, mango leaves—carries symbolic weight, evoking abundance, purity, and rebirth.

Jain Temple Complexes: Geometry and Transcendence

While Hindu temples often emphasize narrative dynamism, Jain temples in Gujarat—particularly from the 11th century onwards—tend toward austere grandeur and geometric intricacy. Built by wealthy merchant patrons, these temples reflect the Jain ideals of non-attachment and inner purity, rendered through dazzling architectural detail.

The most iconic example is Mount Shatrunjaya near Palitana, home to over 800 Jain temples clustered on a hilltop—a sacred geography painstakingly developed over centuries. Climbing to its summit is itself an act of devotion, but it is the temple interiors that reveal the true artistry: ceilings carved like lotus blossoms, marble pillars with filigreed bases, and sanctums lit by natural light filtered through latticed stone screens (jalis).

These temples are often built in white marble and feature highly stylized forms—perfect symmetry, tiered domes, and elaborate spires capped with golden finials. Unlike Hindu temples that focus on darshan (visual contact with the deity), Jain temples emphasize a serene, meditative space conducive to contemplation and circumambulation. Here, architecture becomes a mandala in stone, leading the pilgrim inward.

The famous Dilwara Temples in Mount Abu—while technically in Rajasthan—were built by Gujarati Jain merchants and artisans and reflect this same aesthetic. Gujarat’s contribution to these temples lies not only in design but in the sculptors and masons who traveled across regions, forming a pan-Indian network of temple craft with Gujarati roots.

The Stepwell as Sacred Architecture

Another unique contribution of Gujarat to the architectural canon is the stepwell, or vav—a structure that blurs the lines between utility, ritual, and art. While found elsewhere in India, stepwells in Gujarat are particularly elaborate, often descending several stories into the earth and adorned with intricate carvings.

The most celebrated is the Rani ki Vav in Patan, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Built by Queen Udayamati in the 11th century in memory of her husband, this subterranean temple is a poetic inversion of usual temple architecture—a descent toward the divine, rather than an ascent. Its walls depict Vishnu in his many avatars, female deities, and Nagas (serpent spirits), all carved with a grace that defies the harshness of the sandstone.

Stepwells served both practical and ceremonial functions—collecting rainwater in arid regions and providing a site for ritual purification. In Gujarat’s art history, they represent a fusion of ecological necessity with metaphysical vision, transforming water storage into aesthetic pilgrimage.

Syncretic Forms Under the Sultanate

With the establishment of the Gujarat Sultanate in the 15th century, temple building entered a more precarious phase. Many temples were destroyed or repurposed, yet the artistic dialogue continued. Sultanate architecture introduced Islamic elements—domes, arches, mihrabs—but in Gujarat, these forms often bore the imprint of Hindu and Jain artisanship.

Structures like the Jama Masjid in Ahmedabad (built in 1424) or the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque with its iconic jali window (often called the Tree of Life) reveal a fascinating syncretism. While built for Islamic worship, these mosques often employed Hindu masons who adapted their traditional vocabulary to new religious contexts. Pillars, for example, often resemble those of earlier temples, and jalis display vegetal motifs similar to Jain carvings.

This cross-pollination did not dilute artistic quality—it enhanced it. Gujarat’s Sultanate architecture is some of the most elegant in India, precisely because of its hybrid sensibility, where form and ornament transcend dogma.

Legacy and Contemporary Resonance

Today, Gujarat’s temple architecture continues to be a living tradition. New temples—such as the massive Swaminarayan Akshardham complexes—draw from Solanki and Jain models while employing modern materials and technology. Pilgrimage remains central to spiritual life, and with it, the experience of sacred space as visual and bodily engagement.

Temple conservation projects, especially those sponsored by the Archaeological Survey of India and community trusts, are increasingly sensitive to both historical accuracy and present-day usage. Meanwhile, contemporary architects like B.V. Doshi—a native of Gujarat—have drawn inspiration from temple forms, stepwell geometry, and sacred spatial logic in their modern buildings.

The sculptural idiom, too, survives in the hands of hereditary stone carvers in Saurashtra and Rajasthan who continue to work on temples across India and abroad. While the materials and scale may change, the philosophy of art as an offering remains intact.

Conclusion: The Temple as Cosmos

In Gujarat, the temple is more than a building—it is a diagram of the universe, a vessel for the divine, a stage for the sacred drama of life, death, and liberation. Its architecture encodes theology, mythology, astronomy, and aesthetics into stone, inviting the devotee to walk a path of embodied philosophy.

Gujarat’s temples, whether perched atop hills, hidden in stepwells, or standing in bustling cities, form an enduring archive of its artistic genius. They remind us that in this land, to carve stone was to shape spirit—and to enter a temple was to enter not only a house of god, but a universe in miniature.

Textiles of the Land: Patola, Bandhani, and the Visual Language of Fabric

Gujarat’s textile traditions are among the richest in the world—technically sophisticated, culturally encoded, and visually resplendent. To speak of Gujarati textiles is to enter a universe of pattern and symbolism, where threads carry stories, and where the acts of weaving, dyeing, and embroidery are as sacred as temple carving or manuscript painting.

From the luxurious double ikat Patola saris of Patan to the resist-dyed Bandhani worn during festivals and marriages, textiles in Gujarat are not mere garments; they are visual languages. Every motif, knot, and color choice can signal caste, region, occasion, even spiritual intent. These are fabrics not only of fashion, but of identity, history, and devotion.

This section explores the major textile traditions of Gujarat—Patola, Bandhani, Ajrakh, embroidery, and mashru—while tracing their historical development, symbolic depth, and continued evolution in the contemporary world.

Patola: The Sacred Geometry of Weaving

Among Gujarat’s textile forms, none is more revered—or more labor-intensive—than Patola. Produced in Patan, this double ikat weave is a marvel of precision, requiring the dyeing of both warp and weft threads before weaving, such that when woven together, the design aligns perfectly. This technique, practiced by only a few families in the world, is one of the most complex textile processes known to humanity.

Patola saris were once prized by royalty and nobility across South and Southeast Asia. They were considered auspicious, often used in dowries and rituals, and valued as heirlooms. Their designs are deeply symbolic: elephants for power, parrots for love, dancers for festivity, flowers for fertility. Many motifs are drawn from Jain, Hindu, and even Buddhist iconography, reflecting Gujarat’s syncretic spirituality.

The Salvi family of Patan, custodians of this tradition for over 900 years, trace their lineage to Karnataka but were brought to Gujarat by the Solanki kings. The Salvis continue to produce Patolas today, each sari taking four to six months to complete, and fetching prices in the thousands of dollars. Every Patola is non-replicable, since the hand-dyeing process means each design must be uniquely executed.

As the saying goes, “Padi Patola bhat, faate pan fitey nahin” — Even if a Patola becomes old, its design never fades. It’s not just fabric; it’s permanence woven in dye.

Bandhani: Tied by Hand, Dyed with Devotion

If Patola is the textile of aristocracy, Bandhani is the cloth of the people—worn in weddings, dances, and religious festivals, particularly during Navratri and Shravan. Bandhani (or Bandhej) is a tie-dye technique that involves pinching small areas of fabric, tying them tightly with thread, and dyeing the cloth so that the tied parts resist the dye, creating constellations of dots.

Bandhani is not merely a design—it is a code. Different patterns indicate different communities, statuses, and purposes. A woman wearing a white and red chunri might be newly married; a green and yellow design might signify monsoon festivities. Common motifs include leheriya (waves), trikona (triangles), and moti (pearls), all produced with astonishing precision by artisans working by hand.

Traditionally practiced in Jamnagar, Bhuj, and parts of Rajasthan, Bandhani is often a women-led art form, passed through generations. The dyeing process is communal: one group ties, another dyes, and a third finishes the cloth.

Though it may appear spontaneous, Bandhani requires mathematical planning. Each pattern is pre-conceived, tied on undyed cloth, and developed through multiple dye cycles. The color palette is usually vivid—vermillion, turmeric yellow, indigo blue, emerald green—each shade derived from natural dyes and symbolic of seasonal or ritual meanings.

Ajrakh: Earth-Tone Elegance from the Desert

Another jewel in Gujarat’s textile crown is Ajrakh, a resist-dye technique practiced primarily in the Kutch region by the Khatri community. Unlike Bandhani’s riotous colors, Ajrakh favors a cool, geometric elegance—symmetrical starbursts, mandalas, and checkerboard patterns rendered in deep indigo, madder red, and black.

Ajrakh’s aesthetic is Islamic in symmetry, Vedic in symbolism, and desert-like in tone. It draws on centuries of exchange between Gujarat and the Islamic world, with influences from Persian art and Sindhi design. The process involves block printing using hand-carved wooden blocks and multiple layers of resist-paste and dye baths, often over 14–16 steps. Natural dyes—derived from indigo, alizarin, pomegranate rind, and iron rust—give Ajrakh its characteristic earthy brilliance.

Ajrakh is deeply tied to Sufi devotional culture. The word itself may derive from Arabic azraq, meaning “blue.” In Kutch, Ajrakh cloths are worn by men as turbans and shawls, and by women as skirts and odhnis, particularly during religious rituals and performances of Sufi music.

Artisans like Dr. Ismail Khatri and his family have brought Ajrakh to global attention in recent decades, collaborating with designers and museums while remaining committed to its spiritual and ecological roots.

Embroidery: Threads of Identity and Resistance

No discussion of Gujarati textiles would be complete without the dazzling tradition of embroidery, practiced by diverse communities across the state—Rabari, Ahir, Sodha Rajput, Meghwal, and others. Embroidery in Gujarat is not just embellishment; it is biographical, symbolic, and often subversive.

Each community has its own signature: Rabari work is bold, often featuring mirrors (shisha), stylized animals, and geometric borders. Ahir embroidery is finer, using chain stitch and floral motifs. Sodha Rajput women use silk threads to create peacocks and paisleys that speak of migration and longing.

Embroidery is traditionally women’s work, done after chores, during pregnancy, or in preparation for marriage. It is a way of narrating one’s emotions, dreams, and clan identity. Some pieces even record historical events or local myths. In times of upheaval—such as the Partition—these embroidered cloths became documents of memory and survival.

Today, organizations like Kala Raksha, Kalaraksha Vidyalaya, and SEWA are helping women artisans maintain their heritage while gaining economic independence. Contemporary designers now showcase Gujarati embroidery on global runways, often acknowledging the artisans by name.

Mashru and Other Forms: Hybrids of Form and Function

Another important, if lesser-known, textile is Mashru, once worn by Gujarat’s Muslim communities. The name means “permitted” in Arabic, reflecting Islamic taboos against wearing pure silk. Mashru resolves this tension by combining silk (on the outside) with cotton (on the inside)—a technological and religious compromise woven into the fabric itself.

Mashru is woven with satin weave patterns, creating shimmering stripes and chevrons. Produced mainly in Patan, Mandvi, and Surendranagar, it was historically used for men’s tunics and women’s skirts, particularly among merchant and artisan classes.

Other important traditions include Tangaliya weaving, practiced by the Dangasia shepherds of Surendranagar, which involves embedding dots of contrasting color into the weave by twisting extra threads into the warp—a subtle and rhythmic form that once identified caste and occupation.

From Ritual Cloth to Runway

Today, Gujarati textiles enjoy a global renaissance. Designers like Gaurang Shah, Anita Dongre, and Abraham & Thakore regularly feature Patola, Bandhani, and Ajrakh in their collections. International collaborations, museum exhibitions, and ethical fashion initiatives have further elevated these crafts.

But this popularity is a double-edged sword. Mass production and tourist demand risk diluting quality and cultural meaning. Fortunately, many artisan cooperatives and NGOs are pushing back—advocating for slow craft, fair trade, and generational transmission.

For many artisans, especially women, textile making remains more than a livelihood—it is a ritual, a heritage, a political act. Each tie, stitch, or block is a gesture of survival and expression. In Gujarat, cloth is not a backdrop to life; it is life itself, made visible.

Folk and Tribal Art: Warli, Pithora, and Bhil Expression

While Gujarat is often celebrated for its temple grandeur and textile sophistication, a parallel, equally powerful visual culture has flourished for centuries in its tribal belts and rural settlements. This is a world where art is not confined to canvas or sculpture, but lives in the daily, the seasonal, the sacred, painted on mud walls, created in courtyard rituals, or worn during processions.

Gujarat’s Adivasi (indigenous) and folk communities—including the Bhil, Gamit, Dubla, Warli, and Rathwa peoples—possess dynamic traditions of art that are deeply performative, symbolic, and participatory. These practices are not separated from life; they are life—created for harvests, marriages, births, festivals, and ancestral veneration.

This section explores the major forms of tribal and folk art in Gujarat, especially the Pithora murals, Bhil painting traditions, and ritual aesthetics that challenge dominant notions of “fine” or “primitive” art. Instead, we discover an art of vision and community, where each painted horse or geometric form speaks volumes about the cosmos, kinship, and continuity.

Pithora Painting: The Ritual of Storytelling in Color

The most celebrated tribal art form in Gujarat is Pithora painting, practiced by the Rathwa, Nayaka, and Bhils of central and eastern Gujarat, particularly in Chhota Udepur, Alirajpur, and the Panchmahal district.

Pithora is not merely decorative—it is a ritual offering. Painted on the inner walls of a family’s main room, a Pithora mural is commissioned to fulfill a vow (mannat) made to the deity Baba Pithora, a horse-riding god associated with rain, fertility, and protection. The mural is a gift, a thank-you, and a sacred contract.

Before painting begins, the walls are plastered with cow dung, white clay, and rice flour, creating a ritual surface. The painting is then executed by Lakhindra (traditional painters) under the guidance of Badwa, the community priest. The process is collective and ceremonial, often accompanied by drumming, singing, and feasting.

The imagery is vibrant and dense: rows of horses, each representing a god or ancestral spirit; riders holding swords or flags; sun and moon deities, grain silos, village scenes, trees, and mythic beings. The colors are made from natural and synthetic pigments, and the forms are intentionally stylized and symbolic rather than anatomically precise.

Each element has a prescribed position and meaning. The number of horses, their color, and their accessories all signify the patron’s social and spiritual intent. The composition often stretches across an entire wall, transforming the domestic space into a portable shrine—part art, part altar, part cosmogram.

Pithora paintings are ephemeral. They fade and are painted over, reminding the community that the divine is cyclical, and that spiritual obligations must be renewed. In this sense, Pithora is not an art of permanence, but of living continuity.

Bhil Painting: Dots, Memory, and the Forest

The Bhil tribe, one of India’s largest Adivasi groups, spans across Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan. Their visual language is distinct—marked by pointillism-like dotting, bold forms, and narrative content drawn from oral traditions.

Historically, Bhil paintings were done on walls during festivals or agricultural cycles, using natural pigments and brushes made of twigs or feathers. In the late 20th century, especially through the efforts of institutions like Kala Raksha and Tribal Art India, Bhil artists began transferring these motifs onto paper and canvas, enabling their work to reach galleries and collectors while retaining its ritual heart.

A leading figure in this transformation is Bhuri Bai, who in the 1980s became one of the first Bhil artists to paint on paper. Her work—and that of others like Lado Bai, Sher Singh, and Tukral Bhil—captures everyday life (sowing, hunting, dancing), mythic tales, and environmental themes.

What distinguishes Bhil painting is its use of dots to fill space—not merely as ornamentation, but as a metaphysical pulse, evoking seeds, stars, and spirits. Each dot is a unit of time, a prayer, a presence. Figures—human, animal, divine—are often outlined in bold black and filled with dots of vivid color: ochres, reds, blues, greens. The palette reflects both the forest and the festival.

Themes range from the myth of Bhima and Hidimba to local stories of trickster animals and ancestral feats. In Bhil cosmology, the forest is sentient, gods walk among animals, and every tree has a memory. Painting becomes a way to keep these memories alive.

Warli and Gamit Forms: Line as Ritual

While the Warli people are more prominently associated with neighboring Maharashtra, their presence extends into southern Gujarat, where they bring with them a pared-down but powerful visual idiom.

Warli art is characterized by simple white lines on mud-dung backgrounds, depicting concentric human figures, geometric animals, and scenes of collective life—farming, dancing, marriage processions. These paintings are done with a chewed twig and a rice-paste dye, usually by women during festivals or rites of passage.

In Gujarat’s Valsad and Dang districts, Warli and Gamit communities adapt this style with local modifications—introducing motifs from local flora, agricultural tools, and tribal mythology. Their paintings, while minimal in form, are rich in rhythm, often resembling dance notations or ritual diagrams.

What unites these forms is their circular worldview: humans, nature, spirits all exist in interdependent cycles. The art is not illustrative but symbolic, revealing a cosmology where balance and gratitude are key.

Beyond the Wall: Ritual Objects and Mobile Art

Tribal art in Gujarat is not limited to painting. It includes a vast array of ritual objects, body art, terracotta votives, and ephemeral installations.

- Terracotta horses, often placed at village shrines, represent offerings to deities or ancestors, and resemble those in Pithora paintings.

- Wooden carvings, such as Bhagat idols or spirit effigies, serve as mediums for trance and possession during festivals.

- Body tattooing, once widespread among women, encoded social and spiritual markers through geometric and floral motifs.

- Festive masks and effigies, used in Kavad yatra or Holi processions, mix craft, dance, and theater into a unified artistic event.

These forms challenge Western distinctions between “art” and “craft,” “ritual” and “aesthetic.” For tribal Gujarat, the object is never just a thing—it is a carrier of presence, a participant in cosmological balance.

The Contemporary Moment: Translation and Tension

In recent decades, tribal artists in Gujarat have begun engaging with the contemporary art world, navigating a complex terrain of visibility, authenticity, and commercialization.

Some, like Pithora painters from Chhota Udepur, now exhibit in urban galleries, adapting traditional compositions to modern themes—climate change, urban migration, pandemic scenes—without losing their ritual vocabulary.

Others collaborate with NGOs and design houses to create textiles, murals, and even digital animations. These encounters can be empowering, but also risky—raising questions about appropriation, dilution, and loss of sacred context.

Yet, many tribal artists remain grounded in their communities, continuing to paint walls during harvest festivals, to teach children in schools, and to reassert their identity in a rapidly changing Gujarat. Their art remains an act of cultural sovereignty, as much as aesthetic expression.

Miniature Painting Traditions of Gujarat

Gujarat’s contribution to India’s miniature painting tradition is profound, particularly through the Western Indian style, which developed between the 12th and 16th centuries. Unlike the courtly miniatures of Mughal, Pahari, or Rajput schools that dominate popular imagination, Gujarat’s miniature tradition was rooted in religion rather than royalty, in scriptoria rather than palaces. It flourished not in courts, but in Jain temples, monastic libraries, and the merchant homes of devout patrons.

These miniatures were, first and foremost, part of manuscript culture—hand-painted illustrations accompanying sacred Jain texts such as the Kalpasutra and Kalakacharya Katha. But their visual vocabulary—bold lines, flattened space, stylized forms—would influence Indian painting far beyond Jain circles. They forged an aesthetic that was narrative, symbolic, and utterly distinct, helping to define the visual grammar of early Indian book art.

This section traces the evolution of Gujarati miniature painting, its techniques, visual codes, patronage systems, and its enduring influence on the broader history of Indian art.

The Rise of the Western Indian Style

The Western Indian style is a blanket term used by art historians to describe the distinctive miniature painting idiom that developed in Gujarat and parts of Rajasthan between the 12th and 15th centuries. Its rise coincided with:

- The flourishing of Jainism, particularly among the mercantile classes.

- The transition from palm-leaf to paper manuscripts in Gujarat (among the earliest such transitions in India).

- A deeply rooted scribe-painter guild system, where text and image were planned together.

The earliest examples are found in illustrated copies of the Kalpasutra, a key Jain canonical text recounting the lives of the Tirthankaras, especially Mahavira. Later, secular texts such as fables (Panchatantra), romances (Samarāiccakahā), and historical chronicles were also illustrated, but always with a sacred undertone.

The term “Western Indian” is a bit of an academic abstraction—it groups together works from Gujarat, Rajasthan, and parts of Malwa that share stylistic traits. However, the epicenter of innovation was undoubtedly Gujarat, particularly in cities like Patan, Cambay (Khambhat), Ahmedabad, and Baroda.

Key Stylistic Features

These miniatures are instantly recognizable for their distinctive formal features, which diverge sharply from naturalistic traditions:

- Almond-shaped, protruding eyes, often frontal and exaggerated, suggesting omniscience and presence.

- Flat planes of color, often brilliant reds, lapis blues, saffron yellows, and greens, with little to no shading or modeling.

- Tightly compressed compositions, often with figures crammed into vertical formats or even bleeding into the margins.

- Architectural framing rendered in stylized, schematic forms to create symbolic space, not perspective.

- Hierarchical scaling, where divine or narrative central figures are shown larger regardless of spatial logic.

The aesthetic is not aimed at mimesis but at evoking the sacred and the eternal. It is a language of darshan—seeing and being seen—rather than illusion. Figures are often stylized to the point of abstraction, yet full of symbolic clarity. For example, a figure with four arms or a golden halo immediately cues divinity, while gestures (mudras) signal teaching, meditation, or benevolence.

Many manuscripts include narrative sequencing, with multiple events depicted within a single frame. This is a storytelling method akin to comic panels or medieval Christian art, where the viewer follows a visual journey through time within a bounded space.

The Artists and the Atelier

While most manuscript paintings were unsigned, historical colophons sometimes name the scribe, patron, or monastery, allowing us to reconstruct the working conditions of this tradition. The artists were often part of hereditary guilds, working within Jain temple complexes or near Bhandars (libraries).

They used natural pigments—lapis lazuli for blue, cinnabar for red, gold leaf for ornamentation, and plant-based blacks and yellows. Fine brushes were made from squirrel hair, and burnishing tools were used to polish the page for a radiant effect. The painting was often done after the scribe had completed the text, although some teams worked in tandem.

The use of gold leaf and stippling techniques added a jewel-like quality to the pages. This was not merely decorative—it was symbolic. Gold represented the inner illumination of Jain spiritual ideals, while stippling suggested subtle textures of divine presence.

Patronage and Purpose

The driving force behind this art was not kings, but Jain merchant families—especially the Shvetambara sect, whose emphasis on image-worship and scriptural study created a fertile environment for illustrated texts. Commissioning a manuscript was an act of religious merit (punya), often done during major festivals or life events such as marriage, pilgrimage, or a successful business venture.

These manuscripts were often donated to temple libraries and read aloud during ceremonies. Their small scale made them ideal for private devotion as well. Some manuscripts were lavish, multi-volume undertakings; others were modest but reverent.

The colophons provide not only names and dates, but insights into the mobility of artists and texts. Manuscripts produced in Gujarat were gifted to Jain centers in Jaisalmer, Ujjain, and even as far as Karnataka, creating a network of visual and textual transmission.

Expansion and Diversification

By the 15th century, the Western Indian style began to evolve. Contact with Islamic manuscript traditions, especially under the Gujarat Sultanate, introduced new motifs: floral margins, arabesques, and architectural motifs borrowed from Persian miniatures. Jain artists, always adaptive, absorbed these forms without compromising their narrative clarity.

Secular themes also expanded. Artists illustrated romantic poetry, astrological treatises, and even Tantric texts, often combining Jain and Hindu symbols in the same visual lexicon. For instance, the Samgrahanisutra, a Jain cosmological text, features elaborate diagrams of the cosmic structure—circular mandalas, multi-level universes, diagrams of time cycles—each meticulously painted and annotated.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw the style begin to fragment. Mughal influence, economic shifts, and the decline of patronage affected production. Yet the stylistic DNA of Western Indian painting continued to echo in the Deccan, Marwar, and even the Pahari schools of northern India.

Preservation and Legacy

Today, many of the finest examples of Gujarat’s miniature tradition are housed not in Gujarat, but in international museums—the British Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The National Museum in Delhi, and L.D. Museum and Institute in Ahmedabad, which holds one of India’s most important collections.

Within Gujarat, some Jain Bhandars—such as those in Patana, Idar, and Palitana—still preserve ancient manuscripts, though access is limited. Conservation efforts are ongoing, but challenges abound: humidity, light damage, and political instability have all taken a toll on these fragile treasures.

In recent years, contemporary artists and scholars have sought to revive and reinterpret the miniature tradition. Artists like Gulammohammed Sheikh, while modernist in form, draw upon the layered storytelling, flatness, and symbolic grammar of the Jain miniature. Others have begun to digitally recreate lost manuscripts, making this visual legacy available to broader audiences.

Conclusion: A Sacred Grammar of Vision

The miniature painting traditions of Gujarat, especially within the Western Indian style, offer one of the most coherent and sustained aesthetic traditions in Indian art history. Though modest in scale, they hold vast cosmologies, ethical teachings, and visual innovation within their pages.

In these miniatures, Gujarat gave the world a grammar of sacred vision—where color becomes doctrine, where line becomes law, and where the act of looking becomes a spiritual exercise. These were not paintings to be passively viewed, but to be read, meditated upon, and absorbed. They remain, centuries later, as luminous testaments to a culture that placed art at the heart of understanding the universe.

Colonial Encounters: Artistic Shifts Under British Rule

The British colonial presence in Gujarat, beginning in earnest in the late 18th century and consolidating through the 19th century, marked a dramatic reorientation of Gujarat’s art world. The arrival of European tastes, technologies, institutions, and markets transformed the production, reception, and meaning of art in ways both subtle and seismic.

Some traditional forms—like textile arts—found new global markets, spurring innovation and adaptation. Others, such as religious painting and temple patronage, suffered declines or were relegated to the realm of the “folk.” At the same time, new artistic vocabularies emerged, shaped by colonial art schools, photography, printing presses, and ethnographic exhibitions. A new visual order was taking shape—one in which documentation replaced devotion, classification replaced oral history, and aesthetic judgment became entangled with empire.

This section examines how colonialism reshaped Gujarati art, focusing on four key dynamics: the reconfiguration of patronage, the birth of new institutions, the commodification of craft, and the politics of visibility and erasure.

From Devotion to Display: Shifting Contexts of Art

Prior to British rule, Gujarat’s art had been deeply enmeshed with temple culture, courtly patronage, and ritual performance. Objects were not made for neutral contemplation but were embedded in sacred, social, or community contexts—from Pithora wall paintings to Jain manuscripts to temple sculpture.

The British disrupted these structures by undermining indigenous systems of patronage. Temples lost revenue through land reforms; princely states were annexed or weakened; merchant guilds faced shifting economic conditions. Without patrons, many artisans found themselves untethered from traditional economies, compelled to seek new markets or abandon their crafts altogether.

Art became increasingly secularized and aestheticized. Objects that had once been used in ritual or community life—miniature paintings, metal icons, textiles—were now collected as curiosities, ethnographic specimens, or museum pieces. Their value shifted from ritual power to aesthetic appeal or antiquarian interest.

This shift is particularly evident in the growing museum culture of the 19th century. Institutions like the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery (established 1894) and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London began to collect Gujarati artifacts, often stripped of context but praised for their craftsmanship.

The Rise of Art Schools and Colonial Realism

One of the most visible effects of colonialism was the introduction of European-style art education in India. Inspired by British academies, art schools began to emerge in cities like Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta. In Gujarat, this influence was felt most acutely in Baroda (Vadodara), under the reformist princely ruler Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III.

Sayajirao was both a nationalist and a modernizer. He invested heavily in education and culture, establishing institutions that blended Indian traditions with Western pedagogy. In 1881, the Baroda School of Drawing was founded, eventually evolving into the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Maharaja Sayajirao University by the mid-20th century (covered in more detail in Section 9).

In these schools, artists were trained in perspective, anatomy, chiaroscuro, and oil painting—hallmarks of colonial academic realism. While some artists embraced these techniques to gain access to new forms and audiences, others saw them as displacing Indian visual traditions.

The conflict between indigenous stylization and European naturalism became a central tension in this era. Artists were caught between preserving symbolic systems honed over centuries, and adapting to new visual grammars imposed through colonial taste and institutional reward.

The Ethnographic Gaze: Categorization and Control

British colonialism was not just about economic exploitation—it was also an epistemological project. Art, culture, and craft were documented, categorized, and classified through the lens of ethnography and anthropology, often reducing complex visual systems to “types” or “styles”.

The Colonial Exhibitions and craft surveys—notably George Watt’s Indian Art at the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 and the Catalogue of Indian Manufactures—reduced Gujarat’s vast textile diversity to swatches and samples. Artisans were profiled, measured, and described as part of racial or occupational taxonomies.

Photography, introduced in India in the 1840s, became a tool for documentation and surveillance. Temples were photographed, not for worship but for architectural analysis. Artisans were photographed not as artists, but as members of caste groups. Visual representation became a means of power and control.

Yet, Indian elites also engaged with photography—both as patrons and practitioners. In Gujarat, early Indian photographers such as those from Zaveri and Sons in Ahmedabad began to explore portraiture, family albums, and studio photography, blending Western form with Indian sensibility.

Craft, Commerce, and the Colonial Market

Despite these disruptions, many Gujarati crafts adapted and flourished during the colonial period—particularly textiles, metalwork, and wood carving. The export of Bandhani, Patola, and Mashru expanded, fueled by British interest in “oriental” design and growing international markets.

Textile companies in Manchester and Glasgow replicated Gujarati motifs for mass production, often undercutting local artisans. Yet, the authenticity and quality of handwoven Gujarati textiles remained prized, leading to a niche market for “native crafts” in British households.

Organizations like the Swadeshi movement in the early 20th century also galvanized a resurgence in craft pride. Gandhi himself was deeply influenced by Gujarat’s textile legacy, and the spinning wheel (charkha) became both a political symbol and an artistic tool.

Craft revivalists such as Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and E.B. Havell—though themselves shaped by colonial frames—argued for the spiritual and aesthetic sophistication of Indian art, helping to recenter traditions that had been marginalized under imperial ideologies.

Resistance and Revival: Nationalist Aesthetics

As Indian nationalism gained momentum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, art became a site of cultural resistance. Gujarati artists, thinkers, and reformers began to reclaim traditional forms not just as heritage, but as political expression.

The Swadeshi art movement, though stronger in Bengal, found echoes in Gujarat through figures like Ravishankar Raval, a painter and art teacher who promoted indigenous aesthetics. Raval founded the Kumar magazine and was a vocal advocate of integrating Rajput and folk styles into modern Indian identity.

In temple towns and princely courts, local rulers and Jain patrons continued to commission works, creating a parallel art world that resisted colonial marginalization. Jain scriptoriums remained active, and rural art forms like Pithora and embroidery continued uninterrupted in the domestic sphere.

This duality—disruption and survival, adaptation and defiance—defines Gujarat’s artistic landscape under colonial rule. Even as new institutions emerged and old ones were weakened, art found new paths, sometimes underground, sometimes reimagined.

Conclusion: Between Empire and Expression

The colonial encounter introduced Gujarat’s art to new audiences, tools, and constraints. It redefined what art could be—who could make it, who could value it, and where it could live. In doing so, it left a legacy that is still being negotiated today.

Yet, within and beyond these constraints, Gujarat’s artists and artisans persisted and adapted. They carried forward rituals in paint, stitched memory into fabric, and found ways to keep the sacred alive in secular times.

The story of Gujarati art under colonialism is not one of loss alone. It is also a story of translation, hybridity, and survival—where ancient symbols moved into new forms, and where modernity was not merely imposed, but reshaped by those who received it.

Modernist Movements and Baroda’s Fine Arts Legacy

If the colonial period was marked by disruption and transformation, the decades following Indian independence witnessed a renaissance of artistic experimentation, self-definition, and critical discourse. Nowhere in Gujarat was this more palpable than in Baroda (Vadodara)—a city that, by the mid-20th century, had evolved from a princely capital into a hotbed of modernist art education, innovation, and critique.

At the center of this transformation was the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University, founded in 1950. This institution, envisioned as a secular, interdisciplinary space for visual thinking, catalyzed a radical shift in how art was produced, taught, and understood—not only in Gujarat, but across India. Baroda would soon be home to a generation of artists, teachers, and thinkers who redefined Indian modernism, challenged inherited aesthetics, and sought to reconcile tradition with contemporary realities.

This section explores the rise of Baroda as an art center, the key figures and movements that shaped it, and the theoretical frameworks that emerged from its studios, classrooms, and exhibitions. We trace how Gujarat moved from being a repository of traditional forms to a crucible of artistic dialogue, where local sensibilities met global conversations.

The Visionary Foundation of Baroda’s Faculty of Fine Arts

The establishment of the Faculty of Fine Arts (FFA) at Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU) was a milestone in Indian cultural history. Inspired by the Bauhaus model in Europe and the interdisciplinary ethos of Tagore’s Santiniketan, the Baroda faculty was envisioned not just as a skills-training center but as an aesthetic laboratory.

The driving force behind this vision was Hansa Mehta, a prominent educator, freedom fighter, and then Vice-Chancellor of the university. She believed that art could help forge a new national identity and must be grounded in both Indian and international paradigms.

She invited prominent figures like Markand Bhatt, Ravi Shankar Raval, and especially K.G. Subramanyan—Santiniketan-trained, intellectually rigorous, and politically engaged—to shape the faculty’s direction. With departments in painting, sculpture, art history, and applied arts, the FFA was one of the first institutions in India to blur the boundaries between fine art, craft, theory, and design.

The Baroda Modernists: Key Figures and Practices

The 1960s and ’70s saw the rise of a dynamic group of artists associated with Baroda, often referred to as the Baroda Group or the Baroda School. These artists—many of whom studied and later taught at the faculty—pushed Indian art into new conceptual and formal territories.

K.G. Subramanyan (1924–2016)

A polymath—painter, muralist, scholar, and designer—Subramanyan played a central role in shaping Baroda’s intellectual climate. Deeply influenced by Gandhian thought and his training at Santiniketan, he sought to reclaim indigenous art practices without romanticizing them. His work integrated folk motifs, miniature painting idioms, and modernist abstraction, creating visual essays that were playful, layered, and politically alert. He believed in art as a living language, not a fossilized tradition.

Gulammohammed Sheikh (b. 1937)

A painter, poet, and art historian, Sheikh’s practice moved fluidly between narrative painting and textual collage. His canvases often reimagined history, mythology, and geography, placing Tulsidas beside Dante, or Bhil myths within modern urban landscapes. As an educator, he emphasized critical historiography, helping to decolonize Indian art history from Eurocentric biases.

Jyoti Bhatt (b. 1934)

Known for both his graphic prints and photographic documentation, Bhatt created a stunning visual archive of rural and tribal arts in Gujarat, including Pithora, Mandana, and wall reliefs. His own artwork, especially in printmaking, blends popular iconography and experimental techniques, reflecting a concern with visual democracy.

Nalini Malani, Rekha Rodwittiya, R.B. Bhaskaran, Bhupen Khakhar—each brought their own voice, medium, and political stance to the mix. The Baroda School was never a uniform style, but rather a pluralistic, dialogic space, where questions of gender, caste, nationalism, and urban alienation found visual expression.

Narrative Figuration and the 1981 Exhibition

One of the most influential aesthetic movements to emerge from Baroda was Narrative Figuration. In opposition to the abstraction dominant in Bombay’s Progressive Artists’ Group or Delhi’s formalist painters, Baroda artists foregrounded figures, stories, and socio-political themes.

The landmark 1981 exhibition “Place for People”, curated by Gulammohammed Sheikh, brought together artists like Sheikh, Bhupen Khakhar, Sudhir Patwardhan, and Jogen Chowdhury, emphasizing painting’s narrative power. The show challenged the modernist orthodoxy and reasserted storytelling as a valid, even radical, artistic gesture.

Bhupen Khakhar (1934–2003)

Khakhar’s work stands as a testament to this ethos. A self-taught painter from Bombay who later studied in Baroda, Khakhar used bright colors, everyday scenes, and satirical caricature to explore themes of middle-class life, queerness, and postcolonial disillusionment. His work was autobiographical yet universal—blending the sacred with the profane, the mythic with the mundane.

Khakhar’s You Can’t Please All (1981) and Man in Benares (1982) remain iconic, positioning him as one of the first openly gay Indian artists to tackle sexuality with humor, honesty, and tenderness.

Art History and Critical Theory: Baroda’s Scholarly Edge

Another unique strength of the Baroda Faculty was its emphasis on art history as a critical discipline. While many art schools focused solely on practice, Baroda’s art historians—like Ratan Parimoo, S.V. Vatsyayan, and later Geeta Kapur (who engaged with Baroda though not based there)—sought to challenge colonial and orientalist narratives of Indian art.

The faculty promoted the study of tribal, folk, and vernacular traditions, placing them on equal footing with classical and modern art. This was not simply about inclusion, but about reframing the canon, acknowledging the complexity and plurality of India’s visual heritage.

Baroda’s scholars emphasized the syncretic, contested, and performative nature of art in India. They were among the first to study calendar art, bazaar prints, and popular media as legitimate objects of aesthetic and cultural inquiry—opening doors for contemporary visual culture studies.

Pedagogy and Practice: A Living Studio

The Baroda model emphasized process over product, research over replication. Students were encouraged to visit rural artisans, study Jain manuscripts, engage in mural projects, and collaborate across disciplines. The faculty was not a silo but a living organism—a studio, library, archive, and laboratory rolled into one.

Annual exhibitions, student exchanges, and critical forums fostered debate. The city itself—Vadodara with its princely past, diverse communities, and open-minded cultural institutions—played host to a vibrant ecosystem that nurtured creativity without dogma.

The Legacy Today

Today, the Baroda Faculty of Fine Arts continues to be a vital institution, although it has faced its share of challenges—political interference, funding cuts, and ideological pressures. Yet its legacy endures in the ethos it instilled: criticality, pluralism, and rooted cosmopolitanism.

Baroda-trained artists continue to influence India’s contemporary art scene, both within the country and internationally. Younger artists draw on Baroda’s legacy to explore digital media, performance, ecological concerns, and urban identity—without severing ties to tradition.

The city remains home to private studios, artist residencies, and independent galleries. Institutions like the Heritage Trust and Fine Arts Fair keep the dialogue alive between past and present, regional and global, elite and folk.

Conclusion: A Modernism of Many Voices

Gujarat’s journey into modernism did not mirror the West’s trajectory of rupture and abstraction. It was a modernism of many voices—inclusive of scrolls and lithographs, wall paintings and street scenes, printmaking and oral narrative.

Baroda offered an alternative vision of art-making—experimental yet grounded, scholarly yet open-ended. In doing so, it helped shape a uniquely Indian modernism, one that was not afraid to question, adapt, and imagine anew.

Contemporary Art Practices in Gujarat

In today’s Gujarat, art emerges from a crucible of memory and modernity, where centuries-old craft traditions coexist with conceptual installations, digital interventions, and global curatorial circuits. The state’s contemporary artists move between local idioms and international vocabularies, navigating questions of identity, ecology, politics, and urban transformation. While many draw from Gujarat’s deep well of visual culture—temple sculpture, textile motifs, tribal cosmologies—they do so with a reflexive, critical gaze shaped by postcolonial theory, global art movements, and personal histories.

Contemporary art in Gujarat is not a monolith. It exists in multiple spaces: in city galleries and rural studios, in public interventions and academic settings, in diasporic reflections and homegrown resistances. What unites these diverse practices is a shared condition of flux, a consciousness of Gujarat’s shifting social, political, and cultural realities.

This section examines the artists, institutions, movements, and materials that define Gujarat’s contemporary art scene. We explore not only what is being made, but how it speaks back to history, and forward to a rapidly changing world.

A New Generation: Anchored and Expansive

Many contemporary artists in Gujarat are Baroda-trained, carrying forward the legacy of the Faculty of Fine Arts while forging their own paths. Others emerge from independent trajectories—through design, craft, performance, or architecture. A few notable figures and practices include:

Nilima Sheikh

Though trained at Baroda and closely associated with its faculty, Nilima Sheikh’s work is deeply tied to gender, memory, and place. Her lyrical, layered paintings draw on miniature painting idioms, Kashmiri poetry, and feminist concerns. Sheikh often collaborates with artisans and storytellers, embracing the idea of art as palimpsest—text, image, and voice coexisting on a single surface. Her 2003 work When Champa Grew Up is a searing meditation on gender violence, rendered in soft pigment and scroll format.

Atul Dodiya

Mumbai-based but originally from Gujarat, Dodiya’s eclectic oeuvre includes photo-based realism, installation, and a sharp play with Indian and Western art histories. Works like Father (2000), a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi as a watchful presence, and The Tear Thief (2001), referencing both Bollywood and Baroda painting, demonstrate how Gujarati artists contribute to India’s visual identity at large.

Hema Upadhyay (1972–2015)

Born in Baroda, Hema Upadhyay created installations and photo-collages that investigated themes of migration, displacement, and the fragile architecture of identity. Her work Where the Bees Suck, There Suck I (2008), a miniature city made from scrap metal, speaks poignantly to India’s urban precarity—a theme increasingly relevant in Gujarat’s booming cities.

N.S. Harsha, Amit Ambalal, Rathin Kanji, and a younger generation of Baroda alumni continue to experiment across form and media—pushing the conversation from narrative figuration to digital interventions, environmental art, and performative practice.

Between Tradition and Technology

One of the hallmarks of Gujarat’s contemporary art is its engagement with tradition not as nostalgia, but as critical resource. Artists often incorporate folk motifs, textile fragments, or sacred geometries, but subvert their meanings, questioning their place in modern society.

For example, collaborative textile-based works by designers and artists working with Rabari or Ahir embroiderers may address themes of gender labor or environmental degradation. These are not decorative pastiches but acts of critique—weaving memory into material, resistance into stitch.

At the same time, new technologies are altering how art is made and distributed. Digital printmaking, video art, augmented reality, and AI-driven installations are being explored, albeit more slowly than in major metros. Platforms like Instagram, Behance, and NFT marketplaces have also opened new avenues for Gujarati artists to bypass traditional gatekeepers and engage directly with audiences.

Spaces and Institutions: The Art Ecosystem

Gujarat’s contemporary art scene is anchored by a growing network of spaces, each with its own character:

- Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda continues to train generations of artists while hosting exhibitions and symposia that engage with critical theory and practice.

- Amdavad ni Gufa, designed by B.V. Doshi and painted by M.F. Husain, stands as a landmark fusion of architecture, sculpture, and painting—a playful, almost subterranean gallery space that continues to host contemporary work.

- Conflictorium, an experimental museum in Ahmedabad, functions as a site for art, memory, and social justice. Through interactive exhibits on dissent, protest, and constitutional values, it brings political discourse into the aesthetic realm.

- Kanoria Centre for Arts, also in Ahmedabad, supports residencies, workshops, and exhibitions, providing an important platform for emerging artists.

- ARCH Foundation, Heritage Trust Baroda, and Darpana Academy work at the intersection of community engagement, performance, and public art, often blurring the lines between craft, ritual, and installation.

Yet challenges persist. Unlike Delhi or Mumbai, Gujarat lacks a robust commercial gallery network or consistent public funding for contemporary art. Many artists still rely on teaching, grants, or freelance design to sustain their practice. The polarization of politics, too, casts a long shadow—especially for artists addressing communalism, caste, or gender rights.

Themes and Tensions: What Contemporary Art in Gujarat Speaks To

Across media, Gujarat’s contemporary artists engage with a range of urgent themes:

- Memory and Violence: The 2002 Gujarat riots left a deep imprint on the state’s cultural psyche. Artists like Sheba Chhachhi, Tushar Joag, and others have addressed the aftermath, either directly or obliquely, through works that explore trauma, silence, and resilience.

- Ecology and Urbanization: With rapid development and industrialization, Gujarat faces critical environmental challenges—from disappearing wetlands to polluted coastlines. Artworks that incorporate natural materials or site-specific installations critique these changes.

- Gender and the Body: Feminist artists address both tradition and modernity—interrogating patriarchy within domestic, religious, and state structures. Embroidery, once considered women’s “craft,” becomes a tool of protest and re-inscription.

- Globalization and Migration: As Gujaratis migrate globally—from New Jersey to Nairobi—artists examine the dislocations and hybrids of diaspora life. Themes of rootlessness, longing, and cultural translation permeate much recent work.

- Language and Visuality: Many artists play with Gujarati script, folk rhymes, or temple iconography, reworking them as graphic elements, typographic experiments, or installations. This turns the vernacular into the conceptual, blurring textual and visual boundaries.

Art and Activism: Where They Intersect

In Gujarat, contemporary art increasingly intersects with activism, pedagogy, and community engagement. From public murals to participatory workshops, artists are not just making statements—they are building platforms, especially in rural and marginalized communities.