Nestled at the crossroads of Central Europe, the Czech Republic has long stood as a cultural intersection where Germanic, Slavic, and Latin influences converge. Its territory—home to the ancient kingdoms of Bohemia and Moravia—has served as a canvas for evolving artistic languages since prehistoric times. From medieval altarpieces to groundbreaking modernist structures, Czech art reflects both the endurance of local tradition and the impact of wider European currents.

Art in this land has often mirrored the nation’s complex history—marked by dynastic shifts, religious upheavals, imperial control, wars, and eventually, independence. Yet despite the turbulence, Czech artists continually forged paths that were both distinctly national and daringly original. This combination of resilience and experimentation became a hallmark of Czech visual culture.

Czech art history cannot be confined to the boundaries of modern statehood. Instead, it unfolds as the story of a region whose artists participated in larger European dialogues while also forging unique responses to their immediate surroundings. In Prague, for example, the Gothic spires of St. Vitus Cathedral stand alongside the Cubist House at the Black Madonna—visual proof that Czech artistic identity resists simplification. It is layered, dialogic, and deeply rooted.

During the Middle Ages, Czech lands were integral to the Holy Roman Empire, which brought Germanic artistic conventions alongside homegrown Bohemian traditions. In the Baroque era, Jesuit patrons commissioned awe-inspiring churches and altarpieces designed to captivate the faithful. The 19th century saw the rise of the National Revival, a movement that placed art at the center of a renewed Czech identity under Austro-Hungarian rule. By the 20th century, Czech artists stood at the forefront of European modernism—often pioneering new styles, as seen in the uniquely architectural expressions of Czech Cubism.

Even in times of censorship or foreign domination, Czech art found ways to endure. Whether in church frescoes, Art Nouveau lithographs, or conceptual installations, artists continually returned to questions of memory, belief, place, and identity. The result is a visual history that is neither parochial nor purely derivative, but a dynamic narrative of continuity and change.

This series aims to tell that story in full. We begin with prehistoric artifacts buried in Moravian soil and travel all the way to the globalized works of contemporary Czech artists. Along the way, we will meet court painters and architects, reformers and rebels, ideologues and visionaries. Each era offers insight not only into the art itself but also into the values, beliefs, and historical conditions that shaped it.

In exploring Czech art history, we discover more than just paintings and statues—we encounter a civilization’s self-expression across centuries. It is a journey that proves art does not merely survive the shifting sands of politics and empire—it endures, transforms, and continues to speak.

Prehistoric and Early Medieval Roots

Long before the spires of Prague Castle pierced the sky or the frescoes of Baroque churches dazzled the faithful, the land that would become the Czech Republic was already alive with artistic expression. The prehistoric peoples of Central Europe—first hunter-gatherers, then early farmers—left behind a modest but significant visual legacy: carved figurines, decorated pottery, and ritual objects that reveal the roots of what we can today call Czech visual culture.

Among the oldest known artifacts is the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, discovered in South Moravia and dated to around 29,000 BCE. This small ceramic figure of a woman, with exaggerated features and a stylized form, is one of the earliest known examples of fired clay sculpture in the world. Although its purpose remains debated—was it fertility symbol, idol, or artistic portrait?—its survival suggests a culture already engaged in symbolic representation, long before written language or formal religion.

Dolní Věstonice was not an isolated phenomenon. The region shows evidence of a sophisticated Gravettian culture, complete with engraved bones, mammoth-ivory carvings, and indications of early aesthetic choices—arrangements of patterns, use of symmetry, and deliberate abstraction. While we cannot speak of “Czech” art in a national sense during prehistory, these early artifacts remind us that the urge to create and to symbolize was present here from humanity’s earliest days.

As millennia passed and the Neolithic era brought agriculture and permanent settlements, visual culture became increasingly functional yet expressive. Pottery, often decorated with incised or stamped motifs, reveals a transition from purely utilitarian forms to aesthetic ones. The Linear Pottery culture, and later the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures, left behind richly decorated ceramics and burial goods that reflect evolving spiritual and social hierarchies.

By the first millennium BCE, Celtic tribes such as the Boii (from whom the name Bohemia derives) inhabited the region. Their art, like that of La Tène culture across Europe, featured swirling patterns, stylized animal forms, and finely wrought metalwork—especially in torcs, fibulae, and ceremonial weapons. Czech archaeological sites such as Stradonice and Závist have yielded extraordinary examples of these artifacts, offering a glimpse into a vibrant culture that combined martial prowess with artistic refinement.

With the gradual arrival of Slavic tribes during the early medieval period, art entered a new phase. Unlike the Celts or Germanic peoples, early Slavic art was more modest in material form, owing partly to the migratory and agrarian nature of early Slavic societies. Yet it was rich in symbolic content, especially as pagan beliefs gave way to Christianity.

One of the defining moments in this transitional era was the rise of Great Moravia in the 9th century, the first known Slavic state in Central Europe. Here, art and architecture were shaped by both Eastern Byzantine and Western Latin influences. Churches were built in stone, often modest but carefully constructed, and adorned with frescoes and sculptural reliefs. Fragments of religious carvings and early inscriptional art—some in Glagolitic or early Cyrillic—have been uncovered in places like Mikulčice and Staré Město.

The Christianization of the Slavs, led by missionaries Cyril and Methodius, was not just a spiritual transformation but also a cultural one. With literacy came manuscripts; with religion came icons, reliquaries, and crosses; with church patronage came an early form of sacred art in the region. Unfortunately, little of this early ecclesiastical art survives intact, but archaeological excavations and comparative study help reconstruct its probable character.

As the Přemyslid dynasty consolidated power in the 10th century, laying the groundwork for the Bohemian kingdom, visual art became increasingly institutionalized. Romanesque churches began to rise, featuring stone sculpture, frescoes, and architectural ornamentation that would define the next chapter in Czech artistic development.

What survives from this early period may seem fragmentary, but it is foundational. It tells us that long before the high culture of later centuries, art in the Czech lands already served as a mirror of belief, identity, and memory. From the Venus figurines of Moravia to the first Christian basilicas of Great Moravia, these early expressions set the stage for the flourishing of Czech art in the medieval and modern eras.

Romanesque and Gothic Flourishing (11th–15th Century)

With the consolidation of the Přemyslid dynasty in the 11th century and the Christianization of Bohemia and Moravia largely complete, the Czech lands entered the high medieval period—a time when art became increasingly tied to the Church and the monarchy. During this era, two architectural and artistic styles—Romanesque and later Gothic—dominated the visual culture of the region. Their legacies still define the skylines of Prague, Kutná Hora, and Olomouc today.

Romanesque Foundations

Romanesque art in the Czech lands emerged in the 11th century, as stone churches and monasteries were built across Bohemia and Moravia. This style, characterized by thick walls, rounded arches, barrel vaults, and simple yet powerful sculptural decoration, reflected both the spiritual weight of the Church and the political power of the monarchy. Romanesque art in the Czech context was often austere but profoundly symbolic.

One of the earliest and most important Romanesque monuments is the Rotunda of St. Martin on Prague’s Vyšehrad hill, dating to the late 11th century. With its cylindrical shape and small apse, it exemplifies the Romanesque ideal of stability and sacred geometry. Other surviving rotundas—such as those in Znojmo and Starý Plzenec—suggest a widespread adoption of this form throughout the region.

Monasteries became centers of both religious life and artistic production. The Břevnov Monastery (founded in 993) and Sázava Monastery (founded in 1032) played key roles not only in the development of architecture but also in manuscript illumination and stone carving. Sculpture from this period, while not as elaborate as in later eras, often adorned church portals and capitals with biblical scenes, interlacing patterns, and symbols of divine authority.

While many Romanesque structures were later remodeled in the Gothic or Baroque periods, their core forms remain visible—silent witnesses to the era when Christianity, literacy, and visual art began to take deep root in Czech soil.

The Gothic Transformation

The 13th century brought a stylistic revolution to the Czech lands with the arrival of the Gothic style, initially imported from France and Germany but soon adapted to local conditions. The Gothic era—spanning roughly from the 13th to the early 15th century—was a golden age of Czech medieval art, marked by dramatic architectural innovations, illuminated manuscripts, religious painting, and sculpture.

This transformation was driven in part by the growing power of the Luxembourg dynasty, especially under Charles IV (King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, 1316–1378). A devout and learned ruler, Charles sought to elevate Prague as a spiritual and political capital of Europe, and his patronage launched an extraordinary artistic renaissance.

At the center of this Gothic flowering stands the monumental St. Vitus Cathedral, begun in 1344 under the direction of French architect Matthieu of Arras and continued by the German-Czech master Peter Parler. Parler’s contribution was transformative: he introduced daring rib vaults, intricate tracery, and sculptural portraiture that gave the cathedral a distinctly Bohemian character. His choir stalls, triforium busts, and net vaulting in the choir are masterpieces of late Gothic innovation.

Under Charles IV’s rule, Prague became a hub for artists, theologians, and architects from across Europe. The founding of Charles University in 1348 and the completion of the Charles Bridge around the same time reinforced the city’s role as a cultural beacon.

Religious painting also flourished during this time. The Master of Vyšší Brod, active around 1350, is credited with creating a serene and deeply expressive Madonna Enthroned, part of the Vyšší Brod altarpiece, which reveals a fusion of Byzantine iconography with the emotionalism of Gothic painting. The growing emphasis on human emotion, facial expression, and narrative detail marked a major shift in the spiritual function of art—from didactic symbolism to devotional intimacy.

Gothic sculpture, often integrated into church facades, tombs, and altars, grew more lifelike and dynamic. The tomb of St. John of Nepomuk in St. Vitus Cathedral (completed later in the Baroque period but initiated in earlier styles) reflects a long tradition of saintly commemoration that began in the Gothic era. Even smaller parish churches commissioned crucifixes and statuary that brought the Passion narrative vividly to life.

Beyond Prague, other towns experienced their own Gothic boom. The silver-mining town of Kutná Hora funded the construction of the awe-inspiring Church of St. Barbara, begun in the 1380s. Likewise, the Cistercian monastery in Zlatá Koruna, the Dominican complex in Jihlava, and the royal town of Cheb all display architectural and artistic investments in Gothic grandeur.

The Gothic period also fostered a Czech school of manuscript illumination, exemplified by the Passional of Abbot Wenceslaus and other religious codices produced in monastic scriptoria. These manuscripts combined delicate decoration with theological depth, serving both liturgical and educational purposes.

As the 15th century progressed, however, spiritual unrest began to shake the artistic world. The Hussite movement, a religious reform initiative inspired by theologian Jan Hus, would soon challenge the role of images in worship and set the stage for iconoclasm and change—leading to a new phase in Czech art history.

But the achievements of the Romanesque and Gothic periods remain foundational. They created a sacred landscape still visible today, from cathedral spires to carved portals, reminding us that art in medieval Bohemia was never just ornament—it was an assertion of divine order, national pride, and human aspiration.

The Hussite Era and the Shift in Religious Art (15th Century)

In the early 15th century, the Czech lands entered one of the most turbulent and ideologically charged periods in their history—the Hussite era, named after the reformer and preacher Jan Hus (c. 1372–1415). Hus’s teachings, which challenged the corruption of the Church and called for a return to biblical foundations, did more than ignite a religious movement. They triggered a cultural rupture in which art, once a medium of veneration, became a focal point for debate, destruction, and reinvention.

Theological Crisis and the Question of Images

Before the Hussite movement, religious art in Bohemia largely followed the Catholic norm: sacred figures adorned cathedral walls, altarpieces depicted the life of Christ and the saints, and devotional images facilitated prayer among the faithful. But for Jan Hus and his followers, these practices had grown corrupt. They condemned what they saw as the idolatrous use of images, the lavish materialism of ecclesiastical commissions, and the clerical elite’s control over religious truth.

Hus was deeply influenced by earlier reformers like John Wycliffe, whose writings criticized the accumulation of wealth by the Church and the use of art for display rather than genuine spiritual instruction. While Hus did not advocate for a wholesale rejection of religious art, many of his supporters—especially the more radical Hussite factions—began to see images as distractions from Scripture and as tools of manipulation by a compromised clergy.

This tension led to an era of iconoclasm, particularly after Hus’s execution at the Council of Constance in 1415. In the Hussite Wars that followed (1419–1434), images became targets as well as symbols. Catholic churches were stripped of their altars and frescoes; statues were smashed; gilded objects were melted down or seized. Some reformers went further, asserting that any visual representation of the divine was inherently misleading or sinful.

From Destruction to Didactic Art

Yet the Hussite period was not simply an era of destruction—it was also a time of ideological realignment, in which new forms of religious art emerged. In more moderate Hussite circles, especially those aligned with the Utraquist faction (which sought reform without complete rupture from the Catholic tradition), art began to take on a more instructional role. Rather than emphasizing mystery or miraculous intercession, visual works stressed the moral and doctrinal clarity of the Gospels.

Altarpieces from this period tend to feature more direct, simplified compositions, often centered around Christ’s passion or the Last Supper—especially important to Hussites, who championed communion in both kinds (bread and wine for all believers). In this sense, the Eucharistic chalice became one of the most powerful visual symbols of the Hussite movement, appearing not only in paintings but also in banners, manuscripts, and even on coins.

One of the most striking examples of Hussite-era didactic art is the Třeboň Altarpiece, attributed to the Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece (active c. 1380–1390). Although painted slightly before the height of the movement, its restrained emotional tone and theological depth made it resonate with reform-minded clergy. In fact, much of the art produced just before and during the early stages of the Hussite period would later be repurposed or reinterpreted within new ideological frameworks.

Manuscripts and Vernacular Visual Culture

Another important shift during the Hussite era was the movement toward vernacular language and lay accessibility. This applied not only to sermons and Scripture, but also to visual materials. Illuminated manuscripts began to include Czech-language texts, and imagery was often simplified for lay audiences unfamiliar with Latin or theological nuance.

Some surviving Hussite manuscripts display bold illustrations of biblical scenes, saints, and apocalyptic visions, often rendered in a stark, almost woodcut-like style. These images served to reinforce scriptural authority while avoiding the elaborate ornamentation typical of pre-Hussite liturgical books. Rather than glorify clerical hierarchy, they emphasized Christ’s humanity, the corruption of false priests, and the need for spiritual purity.

Architecture and Public Spaces

While less prominent than painting and sculpture, architecture during the Hussite period also reflected shifting values. Many ecclesiastical building projects were halted, destroyed, or repurposed, as towns and cities aligned themselves with one faction or another. Some churches were stripped bare of decoration, while others became fortified strongholds, like the Hussite bastions at Tábor.

Urban art also took on a propagandistic role. Murals, graffiti, and symbolic carvings—often of the chalice, cross, or scenes of martyrdom—were used to declare loyalty to the movement. The public square, already a site of sermons and political gatherings, became a kind of open-air canvas where the lines between religion, rebellion, and visual culture blurred.

Lasting Impact

By the late 15th century, the religious fervor of the Hussite wars had subsided, but its impact on Czech art remained. The suspicion of religious imagery would persist, echoed centuries later during Protestant reforms. At the same time, the movement had laid the groundwork for a more introspective, locally rooted, and socially conscious artistic tradition—one less beholden to foreign styles or hierarchical patronage.

The Hussite era revealed that in Bohemia, art was never merely decoration. It was theology in color, a political act in paint and stone. And even in destruction, it bore witness to the passions, convictions, and struggles of its time.

Renaissance and Humanism in Bohemia (16th Century)

The Renaissance arrived late in the Czech lands, and it did so under complex circumstances. By the early 1500s, Bohemia had endured not only the Hussite Wars, but also a century of social and religious tension. As a result, the adoption of Renaissance art and thought was not a seamless imitation of Italian models, but rather a localized adaptation—filtered through German influences, shaped by religious divides, and patronized by a layered aristocracy that saw classical aesthetics as a symbol of status, learning, and stability.

The Habsburg Court and Cultural Realignment

In 1526, the House of Habsburg took the Bohemian throne, initiating a new political era that would last nearly four centuries. With this dynastic shift came new artistic preferences. The Habsburgs, steeped in the Renaissance courts of Austria, Spain, and beyond, brought with them a taste for Italianate architecture, court portraiture, and humanist learning. Under Ferdinand I, the Bohemian court in Prague began to resemble other Central European centers where Renaissance ideals were circulating.

This was not, however, a total abandonment of Gothic traditions. In the early 16th century, many artists continued to work in Late Gothic styles, especially in religious commissions, while gradually integrating Renaissance elements—classical motifs, balanced proportions, and naturalistic space. The coexistence of these two vocabularies is one of the hallmarks of the Czech Renaissance.

Architectural Innovation: From Castles to Courtyards

Renaissance architecture made its most visible mark in castle design and noble residences. Bohemian and Moravian nobility embraced the Renaissance style to assert their cultural refinement and political allegiance to the Habsburg court, while still maintaining regional identity.

One of the best examples is the Litomyšl Castle, rebuilt in the 1560s with an elegant arcade courtyard and sgraffito façades—decorative plasterwork etched with classical scenes and geometric patterns. These sgraffito techniques became a signature of Czech Renaissance architecture, adorning the façades of town halls, burgher houses, and manor estates across the country.

Similarly, the Château in Telč, redesigned by Zachariáš of Hradec, displays arcades, stucco ornamentation, and Italianate gardens—a clear statement of Renaissance values adapted to local tastes and building traditions. Architects like Bonifác Wohlmut and Giovanni Maria Filippi, both of whom worked in Bohemia, helped spread the ideals of symmetry, order, and proportion that characterized the new style.

Painting and Portraiture: The Rise of the Individual

In painting, the Renaissance shift is perhaps most evident in portraiture. Influenced by German masters like Lucas Cranach the Elder, Czech artists and patrons began to commission individual portraits not just for royalty, but also for nobles, scholars, and wealthy burghers. These portraits often displayed sitters with books, coats of arms, or instruments—emblems of learning, lineage, and personal virtue.

One of the key figures in this development was Master IW, an anonymous painter active in the mid-16th century whose portraits display a striking realism and sensitivity. His works often reveal both the dignity and the inner life of the subject, aligning with the Renaissance ideal of the individual as a rational, self-aware being.

Religious art continued to be produced, especially in Catholic circles, but it became increasingly subdued in Bohemia. The Reformation—and later, Utraquist and Lutheran influences—had cooled the appetite for elaborate church commissions. Instead, the visual emphasis shifted toward humanist themes, moral allegories, and classical subject matter.

Humanism and the Book Arts

The Renaissance in Bohemia was also deeply tied to literacy and education, with the proliferation of printing presses, humanist scholarship, and vernacular literature. Prague and Olomouc became important centers for book production, and with them came a surge of illustrated texts—ranging from Latin philosophical treatises to Czech-language religious and scientific works.

Czech printers and woodcut artists produced frontispieces, marginalia, and emblematic images that reflected both classical learning and local concerns. The works of Křišťan z Prachatic and Tadeáš Hájek z Hájku, for example, combined astronomy, medicine, and theology with visually sophisticated layouts—emphasizing clarity and rationality.

This visual turn toward clarity, symmetry, and intellectual content distinguished Renaissance art in Bohemia from its more devotional or mystical medieval antecedents. While it lacked the scale and grandeur of Florentine or Roman art, it contributed to a more literate, scholarly form of culture that deeply shaped the Czech elite.

Courtly Splendor under Rudolf II

The pinnacle of Czech Renaissance art came at the end of the 16th century under Emperor Rudolf II, who moved his imperial court to Prague in 1583. Though technically the beginning of the Mannerist and early Baroque period (which we’ll explore fully in the next section), Rudolf’s court still reflected Renaissance ideals of encyclopedic knowledge, scientific curiosity, and artistic patronage.

He brought to Prague an extraordinary collection of artists, alchemists, astronomers, and collectors—including Giuseppe Arcimboldo, known for his fantastical portrait heads composed of fruits and objects. Rudolf’s court also included skilled engravers and illustrators like Aegidius Sadeler, who helped spread Czech art across Europe.

The court’s embrace of natural history, mythological painting, and technical innovation made Prague a beacon of late Renaissance cosmopolitanism, even as Europe edged toward the upheavals of the 17th century.

Baroque Grandeur in the Czech Lands (17th–18th Century)

By the early 17th century, the cultural landscape of the Czech lands had undergone another seismic shift. The Renaissance worldview—rooted in humanism, reason, and balance—was soon eclipsed by the emotional intensity and visual dynamism of the Baroque. Unlike the cautious classicism of the preceding century, Baroque art in Bohemia and Moravia was bold, theatrical, and deeply entwined with religious and political authority. At the heart of this transformation was the Catholic Counter-Reformation, which sought to reassert spiritual dominance through art that moved the soul and glorified the Church.

After White Mountain: A Political and Cultural Reset

The defining event of the early Baroque period was the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, where the Protestant forces of Bohemia were decisively defeated by the Catholic Habsburgs. This victory not only ended the Bohemian Revolt, it also led to the forced re-Catholicization of the region. Protestant nobles were exiled or executed, and Catholic institutions—especially the Jesuits—took the lead in reshaping the cultural and spiritual landscape.

Art became a central tool of this reassertion. The Baroque style, with its sweeping motion, dramatic contrasts of light and dark, and emotionally charged compositions, was ideally suited to express the triumph of faith and the power of the divine. Churches were rebuilt or newly founded, interiors flooded with gilded stuccowork, ceiling frescoes, and elaborate altarpieces.

This was not merely aesthetic—it was strategic. The aim was to awe, instruct, and inspire. Baroque art in the Czech lands was didactic in nature, designed to reclaim hearts and minds through sensory immersion and spiritual drama.

Architecture: Theatrical Space and Divine Geometry

Nowhere is the Baroque transformation more visible than in Czech ecclesiastical architecture. Inspired by Italian models, architects began to favor oval floor plans, massive domes, sweeping staircases, and illusionistic ceiling paintings that visually dissolved the boundary between heaven and earth.

A key figure in this transformation was Giovanni Battista Santini-Aichel, a Czech-born architect of Italian descent, whose Baroque Gothic style blended medieval verticality with Baroque dynamism. His masterpiece, the Church of St. John of Nepomuk at Zelená Hora, is a marvel of sacred geometry: a five-pointed star floor plan, swirling spatial flow, and mathematical symbolism interwoven into every detail. Built between 1719 and 1727, it stands as one of the most innovative Baroque structures in Europe.

Other notable works include the Church of St. Nicholas in Prague’s Lesser Town (Malá Strana), designed by Christoph Dientzenhofer and later completed by his son Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer. Its undulating façade and soaring dome are quintessentially Baroque, merging spiritual elevation with architectural virtuosity.

Palaces, gardens, and even rural chapels embraced the same aesthetic language. The Clementinum, once a Jesuit college in Prague, became a showcase of Baroque interiors, while the Kroměříž Archbishop’s Palace combined aristocratic luxury with religious decorum.

Painting and Sculpture: Drama, Emotion, and Devotion

Baroque painting in Bohemia emphasized movement, contrast, and devotional intensity. Altarpieces typically depicted the Crucifixion, Assumption, or saintly martyrdoms with an emotional pitch that aimed to stir the viewer into spiritual contemplation or awe.

Two names dominate Czech Baroque painting: Karel Škréta and Petr Brandl.

- Karel Škréta (1610–1674), a Protestant who converted to Catholicism after White Mountain, became one of the most important court painters of his time. His works fused Italian Baroque composition with Northern precision, often focusing on biblical and hagiographic scenes. His altarpiece of St. Wenceslas in St. Vitus Cathedral remains a major national and religious icon.

- Petr Brandl (1668–1735) brought Baroque theatricality to its peak. His paintings are known for their bold brushwork, intense chiaroscuro, and psychological depth. Whether portraying apostles, prophets, or penitent saints, Brandl’s figures seem to emerge from shadow into revelation. His painting of St. Thomas touching the wounds of Christ, with its lifelike tension and tactile realism, is among the most powerful works of Czech Baroque.

Sculpture also flourished, often in dramatic poses and flowing drapery. The statues that line the Charles Bridge in Prague—many created by Matthias Braun and Ferdinand Maxmilian Brokoff—are among the most iconic Baroque artworks in the Czech Republic. These figures, caught in mid-gesture or prayer, transform the bridge into a procession of saints and martyrs, turning public space into a catechism in stone.

Matthias Braun’s Allegory of Religion, carved in sandstone at the Kuks spa complex, is another triumph—depicting Faith as both maternal and monumental, serene yet unyielding.

Baroque in the Regions: Moravia and Beyond

While Prague remained the artistic heart of the kingdom, the Baroque style spread across the Czech lands. Moravian towns like Olomouc, Kroměříž, and Znojmo built churches, seminaries, and bishoprics in the Baroque style, each competing in splendor. Rural pilgrimage churches—such as Svatý Hostýn and Vranov—also featured frescoes and architectural flair, testifying to the depth of Catholic revival beyond the capital.

The Jesuits and other Catholic orders played a decisive role in spreading artistic education and maintaining high standards. Their emphasis on iconography, rhetoric, and visual impact shaped a generation of artists who learned not only technique, but the theological intentions behind each brushstroke and chisel.

Legacy of the Czech Baroque

By the end of the 18th century, the Baroque era was giving way to Enlightenment rationalism and Neoclassical restraint. Yet the Czech Baroque left an indelible mark—not only in its monumental churches and public sculpture, but in the Catholic visual culture that persists to this day. Even during later secular periods, the emotional power and technical mastery of Baroque art continued to inspire reverence and pride.

In the Czech lands, the Baroque was not merely imported—it was made local. It became part of the visual and spiritual DNA of Bohemia and Moravia, expressing both imperial grandeur and intimate piety. Above all, it proved that art could do more than decorate—it could persuade, elevate, and transform.

National Revival and the Birth of Modern Czech Identity (19th Century)

The 19th century was a time of profound transformation in the Czech lands, not only politically and socially but also culturally. As the Habsburg monarchy tightened its grip and Germanization policies spread through the empire, Czech artists, writers, and intellectuals responded with a movement that sought to recover, celebrate, and reimagine Czech national identity. This movement—known as the National Revival (Národní obrození)—gave art a new mission: to serve as the visual language of a people rediscovering their voice.

Unlike previous eras when art had primarily served religious or aristocratic patrons, the art of the National Revival addressed a broader public. It looked to the past for inspiration—particularly to the medieval kingdom of Bohemia—and cast its gaze forward toward the dream of cultural sovereignty. Through painting, sculpture, architecture, and design, Czech artists gave form to the idea of a nation long submerged under foreign rule but never extinguished.

Art as Patriotism: The New Role of the Artist

The National Revival was primarily a linguistic and literary movement at first, championed by figures such as Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann, who worked to restore the Czech language and chronicle its literature. But by the mid-19th century, visual artists began to take part in the cultural project, contributing to historical memory and national myth-making.

Artists turned to themes drawn from Czech legends, medieval history, and Slavic folklore. The visual arts became a way to assert Czech identity in public space: through portraits of national heroes, illustrations of folk tales, and grand historical scenes that reconnected a modern people with their imagined medieval roots.

One of the earliest and most influential painters of this era was Josef Mánes (1820–1871), who came from a distinguished artistic family. Mánes combined Romantic sensibility with deep historical knowledge, and his works—whether decorative calendars, genre scenes, or murals—are imbued with patriotic sentiment. His famous Lunette Paintings for Prague’s Old Town Astronomical Clock allegorize Czech life through idealized depictions of rural labor and seasonal change, rooting national identity in the land itself.

Another significant figure was Jaroslav Čermák, who studied in Paris and brought a heroic, French-inspired historical style to Czech subjects. His dramatic canvases, such as “The Wounded Montenegrin”, linked the Czech national cause with broader Slavic struggles for liberation, reinforcing pan-Slavic solidarity through visual allegory.

Architecture and Urban Renewal: Czech Style in Stone

Architecture played a central role in the National Revival, particularly in Prague, where the city’s skyline was reshaped to reflect Czech cultural aspirations. The dominant style was Neo-Renaissance, seen as a revival not just of classical harmony but of the glory days of Charles IV’s medieval Bohemia.

The crowning achievement of this architectural movement was the National Theatre (Národní divadlo), designed by Josef Zítek and opened in 1881 (and reopened in 1883 after a fire). The building itself was funded by public donations, making it both a literal and symbolic product of national will. Every element—from the façade sculpture to the interior murals—was designed to express Czech pride.

Inside, the theatre’s ceiling is adorned with allegorical paintings by Mánes, while the sculptural program includes Slavic deities and Czech historical figures. This was not merely decoration—it was a visual manifesto of cultural self-determination. Other Neo-Renaissance buildings followed, including the Rudolfinum concert hall and the National Museum, both of which served as temples to Czech intellectual and artistic life.

History Painting and the Search for National Icons

The 19th century saw a flourishing of history painting, a genre that sought to elevate key events and figures from the Czech past. Artists like Václav Brožík became famous for large-scale canvases that dramatized moments such as Jan Hus before the Council of Constance, turning historical narrative into visual theater.

Brožík’s paintings, though academically composed, had political overtones. In a time when Czech representation in the imperial court was limited, art galleries and public exhibitions became spaces where the Czech view of history could be asserted. This was not only about accuracy—it was about imagination, memory, and morale.

Historical subjects also found their way into sculpture. Emanuel Max’s statue of St. Wenceslas and later Josef Václav Myslbek’s monumental Wenceslas statue in Prague (completed in the early 20th century) turned Bohemia’s patron saint into a symbol of national resistance and endurance.

Folk Motifs and Decorative Art

Alongside grand history painting and monumental architecture, the Revival also fostered an appreciation for folk art and traditional design. Crafts, embroidery, ceramics, and vernacular architecture were studied, cataloged, and revived as expressions of authentic Czech spirit. The painter Mikoláš Aleš, for example, integrated folk motifs and rustic themes into his illustrations and murals, blending the heroic with the homely.

This aesthetic had political implications. Folk art was seen as untainted by foreign influence, a pure expression of the people’s soul. By elevating these forms into national symbols, Revival artists argued that Czech identity was not imposed from above but grew organically from below.

Public Art and National Space

As the 19th century drew to a close, public art became a key battleground for cultural identity. Memorials, allegorical statues, and mural cycles were installed in town squares, schoolhouses, and train stations. These works reinforced a common visual vocabulary of Czech heroes—Libuše, Přemysl, Charles IV, Jan Žižka, Hus, and Komenský—and often echoed literary and musical themes popularized by figures like Smetana and Neruda.

Through this integration of art and public life, the National Revival made a lasting impact. It did not achieve political independence—that would come only in the 20th century—but it succeeded in creating a sense of cultural sovereignty, with visual art as one of its primary weapons.

Secession, Symbolism, and the Czech Art Nouveau Movement (Late 19th – Early 20th Century)

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, the Czech art world underwent a shift from historicism and nationalism toward something more lyrical, psychological, and formally experimental. This transition found its fullest expression in Art Nouveau—or as it was known in the Czech context, Secese. What began as a decorative style evolved into a visual philosophy that sought harmony between nature, design, and the inner self.

For Czech artists, Art Nouveau was not a break from tradition—it was an evolution. They blended the romantic nationalism of the National Revival with the stylistic innovation of the Vienna Secession and French Symbolism, creating a visual culture that was at once cosmopolitan and distinctly Czech. The result was a flourishing of painting, architecture, poster design, decorative arts, and book illustration that defined the fin de siècle in Bohemia and beyond.

Alphonse Mucha and the Rise of the Czech Art Nouveau Icon

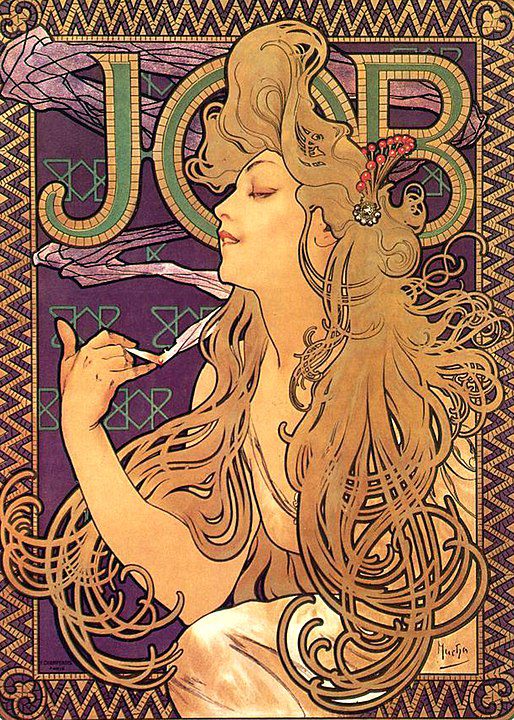

No name is more closely associated with Czech Art Nouveau than Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), whose stylized posters of elegant women entwined with floral motifs became the visual face of the movement. Mucha began his career in Paris, where his 1894 poster for actress Sarah Bernhardt’s play Gismonda catapulted him to fame. The lithograph, with its halo-like composition and intricate lines, set the template for what would become known as “le style Mucha.”

Mucha’s posters for Bernhardt and for commercial products—such as Job cigarettes, Moët & Chandon, and Nestlé—brought decorative art into everyday life. His work emphasized curvilinear forms, pastel palettes, and symbolic femininity, often rooted in Slavic myth and allegory. Yet while he achieved international success, Mucha never abandoned his national identity.

Returning to Prague in the early 20th century, Mucha undertook his most ambitious and personal project: The Slav Epic (Slovanská epopej), a monumental series of 20 massive canvases depicting the spiritual and cultural history of the Slavic peoples. Painted between 1910 and 1928, the cycle was a labor of love—uncompromising in its scale and idealism. Though not strictly Art Nouveau in style, it was born from the same symbolic impulse: to fuse art, myth, and identity into a single visual language.

Czech Secession and the Search for Style

While Mucha became the face of Art Nouveau abroad, in Bohemia the movement took on broader dimensions. Artists, architects, and designers began exploring the relationship between form and function, tradition and modernity. Influenced by the Vienna Secession (founded in 1897 by Gustav Klimt and others), Czech artists formed their own collectives, such as Mánes Union of Fine Arts, which promoted progressive exhibitions and journals.

Architecture became one of the most fertile fields for Secession aesthetics. In Prague, Osvald Polívka and Antonín Balšánek designed the Municipal House (Obecní dům), completed in 1912, as a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk). Its façade features allegorical sculpture by Ladislav Šaloun and murals by Mucha, while the interior brims with stained glass, stucco, and decorative ironwork. The building is both a palace of civic pride and a physical embodiment of Secession ideals.

Elsewhere, architects such as Jan Kotěra and Josef Fanta adapted Art Nouveau to Czech vernacular traditions. Kotěra’s Peterka House on Wenceslas Square, with its flowing ornament and organic detail, helped establish him as a bridge between Art Nouveau and the emerging modernist styles. Fanta’s Main Railway Station in Prague—still operational—stands as one of the most ornate transportation hubs in Europe, its dome and stained glass imbued with turn-of-the-century optimism.

Symbolism and the Inner World

Parallel to decorative Art Nouveau, Czech painters began to explore more introspective, symbolist themes—often mystical, erotic, or mythological. This strand of Secession art reflected growing interest in the subconscious, the spiritual, and the metaphysical, influenced by writers like Maeterlinck and artists such as Odilon Redon.

One of the leading Czech Symbolists was Max Švabinský, whose early works portrayed idealized figures and allegorical landscapes in a manner reminiscent of Art Nouveau, but with a psychological depth that aligned more with Symbolism. His later graphic works and portraits maintained the technical finesse of the movement while adopting a more introspective tone.

František Kupka, meanwhile, broke entirely new ground. Though his early works were symbolist in theme, Kupka gradually moved toward pure abstraction, making him one of the pioneers of non-objective painting in Europe. His exploration of color, movement, and music in works like Amorpha: Fugue in Two Colors (1912) laid the groundwork for modernist experimentation, and his theoretical writings would influence artists well beyond Czech borders.

The Decorative Arts: Everyday Art for a Modern Nation

One of the great ambitions of the Art Nouveau movement was to eliminate the divide between high art and design, between beauty and utility. In the Czech lands, this vision found expression in furniture, typography, ceramics, stained glass, and book illustration.

Designers and craftsmen—many trained at schools such as the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (UMPRUM)—developed patterns and motifs that blended floral elegance with Slavic folklore. Illustrated books from this era are masterpieces of layout and ornament, featuring contributions from artists like Vojtěch Preissig, who also experimented with early modernist design.

Jewelry and glasswork from the Jablonec nad Nisou region gained international acclaim for their refinement and originality, continuing the Czech tradition of technical excellence in decorative media.

Art Nouveau in the Czech Context: Beyond Ornament

Though Art Nouveau is often associated with surface beauty, in the Czech lands it carried deeper meanings. It was a vehicle for national expression, a synthesis of European trends and local heritage. Mucha’s Slavic allegories, Kotěra’s architecture, Kupka’s abstract experimentation—these were not simply aesthetic exercises. They were cultural statements: of a people asserting their place in modern Europe without abandoning their past.

Moreover, the movement coincided with political transformation. As the Austro-Hungarian Empire weakened in the early 20th century, Czech artists used Art Nouveau and Symbolist idioms to imagine a new national future. This future would soon become reality with the founding of Czechoslovakia in 1918, a moment that marks the transition to the modernist avant-garde.

Cubism and Avant-Garde Experimentation in the First Republic (1918–1938)

The birth of Czechoslovakia in 1918, following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ushered in a brief but brilliant period of cultural autonomy. Known as the First Republic, this era—between World War I and the Nazi occupation—saw an explosion of creativity in architecture, design, painting, and graphic art. The Czechs, long innovators within imperial constraints, now had the freedom to lead rather than follow. Nowhere was this more evident than in their embrace of Cubism, Functionalism, and a host of avant-garde movements that made Prague one of the most experimental artistic capitals of interwar Europe.

While Cubism is most often associated with painters like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in France, the Czech interpretation went far beyond the canvas. It took root in architecture, furniture, ceramics, and typography, producing a style that was both intellectually rigorous and distinctly local. More than a stylistic trend, Czech Cubism was a cultural assertion—a declaration that modernity would be met not with imitation, but with originality.

Czech Cubism: A Total Style

Between 1911 and the early 1920s, a group of Czech architects and artists developed a version of Cubism that was radically different from anything elsewhere in Europe. They sought not just to fracture perspective on a canvas, but to apply the Cubist principle of geometric fragmentation to three-dimensional space and object design.

The key figures in this movement were Pavel Janák, Josef Gočár, and Vlastislav Hofman. Trained in historicist and Secessionist traditions, they broke away from Art Nouveau curves in favor of angular planes, crystal-like forms, and dynamic faceting. These architects believed that buildings, like paintings, could express energy and movement—and that every object, from a façade to a doorknob, could embody modern thought.

The most famous example is the House of the Black Madonna (Dům U Černé Matky Boží) in Prague, designed by Gočár in 1912. It features Cubist windows, railings, and interior details, and originally housed the Orient Café, a rare complete Cubist interior. Other striking examples include Janák’s Fara House in Pelhřimov and Cubist villas in the Prague suburbs of Vyšehrad and Dejvice.

Czech Cubism extended to furniture and ceramics, with tables, chairs, lamps, and vases shaped according to faceted, crystalline logic. The Artěl cooperative and the Královská dílna (Royal Workshop) were key producers of these experimental designs, fusing artistry with utility in ways that prefigured Bauhaus ideals.

Painting and the Czech Avant-Garde

In parallel with architectural Cubism, Czech painters also engaged with modernist abstraction and experimentation. Artists such as Bohumil Kubišta, Emil Filla, and Antonín Procházka adapted Cubist ideas to their own expressive purposes, often blending them with Expressionist color and symbolic content.

- Bohumil Kubišta (1884–1918), deeply philosophical in temperament, sought to reconcile modern formal innovation with spiritual depth. His still lifes and portraits are marked by luminous color and geometric structure, imbued with inner tension and moral clarity.

- Emil Filla, a central figure of the Skupina výtvarných umělců (Group of Fine Artists), fused analytic Cubism with Central European pathos. His works often retained recognizable human figures and objects, filtered through planes and contours that emphasized both intellectual rigor and psychological intensity.

Filla also played a leading role in Czech art publishing. As editor of the avant-garde journal Volné směry (Free Directions), he helped spread Cubist and modernist ideas to a wide audience, encouraging dialogue between artists, architects, and writers.

Devětsil and the Fusion of Art, Language, and Life

As the 1920s progressed, Cubism gave way to even more radical forms. The Devětsil (Nine Forces) movement, founded in 1920 by a group of poets, artists, and theorists—including Karel Teige, Jaroslav Seifert, and Toyen (Marie Čermínová)—sought to unify all the arts under a modern, utopian vision.

Devětsil embraced Poetism, a uniquely Czech avant-garde ideology that celebrated play, imagination, and sensory experience as the foundation of art. Influenced by Dada, Surrealism, and Constructivism, Poetism rejected bourgeois seriousness and emphasized everyday joy—often through photomontage, kinetic typography, and film-inspired layouts.

Toyen and Jindřich Štyrský later moved toward Surrealism, becoming important members of the international surrealist network. Their works explored dreams, eroticism, and subconscious imagery through a distinct visual language that stood apart from French Surrealism.

Teige, meanwhile, became one of Europe’s leading modernist theorists. His designs for book covers and posters, with bold sans-serif type and Constructivist composition, set new standards for graphic design as modern art. In his treatise The Minimum Dwelling, he also advocated for rational, affordable architecture as a social and aesthetic ideal.

Functionalism and the Modernist City

By the 1930s, as Cubism and Poetism gave way to more practical concerns, Czech architecture moved into a Functionalist phase. This style emphasized clean lines, flat roofs, unornamented facades, and rational floor plans, reflecting the belief that form should follow function.

Functionalism found a major showcase in Zlín, an industrial city rebuilt by the Baťa shoe company along modernist principles. Here, architecture became part of a social and economic project—efficient, hygienic, and ordered. The Baťa skyscraper, built in 1938, was one of the tallest buildings in Europe at the time and remains a striking symbol of Czech industrial modernism.

In Prague, Functionalist housing projects like Baba Estate (Baba kolonie) and the Villa Tugendhat in Brno (designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) pushed Czech architecture to the forefront of the European avant-garde.

A Short-Lived Golden Age

Despite its extraordinary achievements, the First Republic’s avant-garde had only a brief window in which to flourish. The rise of authoritarian regimes across Europe, combined with growing tensions between Czechs and Germans within the new state, created a climate of uncertainty. By the time Nazi Germany annexed the Sudetenland in 1938 and occupied the rest of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939, the avant-garde was in retreat.

Many artists went into exile, others were silenced or persecuted. The outbreak of World War II would mark the end of this luminous chapter—but not its legacy.

Art Under Occupation: WWII and the Communist Era (1939–1989)

The 20th century’s darkest decades cast long shadows over Czech cultural life. Beginning with the Nazi occupation of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939, followed by the Communist takeover in 1948, Czech artists endured two totalitarian regimes that sought to control visual culture from above. Art during this time was a contested space—used for propaganda, shaped by censorship, but also deployed in acts of resistance, satire, and coded expression.

This period did not extinguish Czech artistic creativity. On the contrary, it compelled artists to navigate systems of surveillance and control, often forcing them to find new symbols, techniques, and mediums. The result was a body of work that is at once visually inventive and historically poignant, reflecting the resilience of a nation’s spirit under foreign and ideological rule.

Under the Nazis: Suppression and Exile

The Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia (1939–1945) brought a swift end to the vibrant artistic scene of the First Republic. German authorities closed avant-garde journals, banned modernist exhibitions, and seized works considered “degenerate” or politically suspect. Public life was rapidly militarized, and artists who were Jewish, politically active, or associated with the avant-garde were targeted.

Toyen and Jindřich Štyrský, associated with the Czech Surrealist movement, worked in secrecy during the war, creating dark, dreamlike compositions that expressed despair, eroticism, and subconscious resistance. Toyen’s wartime drawings—such as her Horror Cycle—are haunting responses to the violence and absurdity of occupation.

Many artists fled or were silenced. František Kupka, by then living in France, avoided direct persecution but remained a symbolic figure of Czech modernism in exile. Others, like painter and sculptor Otakar Švec, survived the war but later struggled under communism.

While overt resistance was dangerous, some artists joined underground movements or contributed to samizdat (clandestine publishing) and secret exhibitions. Art became a quiet act of defiance, preserving memory and identity when official culture demanded conformity.

Postwar Hope and Communist Takeover

The end of World War II in 1945 brought a brief moment of renewed optimism. Prague’s galleries reopened, émigré artists returned, and there was a sense that Czech art might reclaim its global stature. However, the Communist coup of 1948 altered this trajectory dramatically.

The new regime quickly imposed a Soviet-style cultural policy, modeled on Stalinist Russia. Art was expected to conform to Socialist Realism—a prescriptive style that depicted heroic workers, idealized peasants, party leaders, and scenes of industrial progress. Individualism, abstraction, and religious or nationalist themes were discouraged, if not banned outright.

Institutions were purged or restructured. The Union of Czechoslovak Artists became a tool of ideological enforcement, and careers could rise or fall based on political loyalty. State commissions replaced private patronage, and exhibitions were tightly controlled.

Artists like Karel Pokorný and Josef Malejovský produced monumental public sculptures in the Socialist Realist style, while painters like František Gajdoš created pastoral scenes that echoed state narratives. While some genuinely embraced these ideals, many others complied to survive.

Dissent and the Underground: Art in the Grey Zones

Despite official control, the 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of alternative artistic communities that operated at the margins or beneath the radar. Abstract painting, conceptual art, and surrealist practices persisted quietly in studios, salons, and unofficial exhibitions.

The Brno circle, artists such as Vladimír Boudník and Mikuláš Medek, developed a raw, expressive form of abstraction that explored texture, violence, and spiritual crisis. Medek’s layered, encrusted surfaces hinted at inner turmoil, religious suffering, and psychological wounds—forms of expression that eluded censorship through ambiguity.

Boudník, a factory worker by day, invented Explosionalism, a spontaneous method of printmaking that involved chance and material experimentation. His work influenced Bohumil Hrabal, whose prose captured similar absurdities and ironies of Czech life under communism.

The 1960s also saw a brief cultural thaw during the Prague Spring (1968), when censorship loosened, and new artistic currents flourished. The Šmidra group, composed of young conceptualists, mocked official art through performance, parody, and absurdism. Jiří Kolář, a poet-artist, pioneered collage and visual poetry that evaded dogma through formal innovation.

However, the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968 crushed the reformist movement and ushered in a period of “normalization.” Artistic freedom was curtailed once again, and many artists faced renewed surveillance or blacklisting.

Public Monuments: Heroism and Irony

In public space, monumental art became a tool of state narrative—but even here, contradictions surfaced. Otakar Švec’s statue of Stalin in Prague’s Letná Park, unveiled in 1955, was the largest of its kind in Europe. But its oppressive scale, coupled with Švec’s private ambivalence (he took his own life shortly before the unveiling), made it a symbol of authoritarian overreach. The statue was dynamited in 1962 after Stalin’s fall from favor.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a younger generation of sculptors and conceptual artists responded with ironic, subversive works, often staged unofficially. David Černý, though emerging only in the final years of communism, would later carry this tradition into the post-1989 world, with provocative public art that confronted history with sarcasm and spectacle.

Art as Memory and Persistence

Throughout the Communist era, Czech artists maintained a parallel culture: one official, controlled, and ceremonial; the other underground, introspective, and occasionally defiant. Exhibitions were held in private homes, churches, and hidden venues. Art circulated through photographs, letters, and foreign contacts. Even when unseen, it continued.

This resilience culminated in the Velvet Revolution of 1989, a largely peaceful uprising in which artists, playwrights (notably Václav Havel), and musicians played vital roles. The fall of communism not only restored freedom of expression but also released decades of pent-up creative energy that would shape a new era of Czech contemporary art.

Velvet Revolution and the Postmodern Turn (1989–2000s)

When the Velvet Revolution unfolded in November 1989, it was not simply a political transition—it was a cultural rebirth. For Czech artists, the collapse of the Communist regime meant more than the end of censorship; it meant the opening of possibilities. What had long been fragmented into official and underground spheres could now emerge into public view. Exhibitions, publications, and installations once hidden from state scrutiny found new platforms. Czech art entered a postmodern moment, shaped by freedom, uncertainty, and a reckoning with the past.

Post-1989, the Czech Republic faced the challenge of defining its cultural identity in a democratic, globalized world. Artists were no longer hemmed in by ideological dictates, but also no longer unified by resistance. The question shifted: What does Czech art mean when it is finally free?

New Freedoms, New Markets

The early 1990s were a time of experimentation and chaos. State-sponsored galleries lost funding, while private dealers and collectors emerged, some with little regard for curatorial standards. Artists once marginalized were suddenly celebrated, while others struggled to adapt to the demands of a market-driven, pluralist culture.

Many institutions reinvented themselves. The National Gallery in Prague, under new leadership, began to mount major exhibitions of both Czech modernism and international contemporary art. New artist-run spaces and alternative venues sprang up in cities like Brno, Ostrava, and Plzeň, while commercial galleries filled the void left by collapsed state structures.

Artists had access to foreign residencies, funding, and audiences for the first time in decades. But the newfound openness also brought questions: Would Czech art now be absorbed into broader European trends, or retain its local specificity? Could it remain critical in a consumerist age?

David Černý and the Rise of Satirical Monumentality

One of the first and most visible post-revolutionary artists to answer these questions with flair was David Černý (b. 1967). A sculptor with a taste for the absurd and the confrontational, Černý shot to fame in 1991 when he painted a Soviet tank pink—a guerrilla act that transformed a war memorial into a critique of occupation and political kitsch.

Since then, Černý’s public works have become landmarks of Czech postmodernism. His “Babies” (crawling infant sculptures with barcode faces) on the Žižkov TV Tower confront notions of surveillance and dehumanization. His “Entropa”, installed in Brussels in 2009 during the Czech EU presidency, featured intentionally provocative stereotypes of each European nation—including a Czech Republic made of LED lights endlessly blinking “EU.”

Černý’s work is deliberately controversial, challenging viewers to confront the absurdities of nationalism, authority, and memory. His sculptures are not just jokes—they are post-totalitarian monuments, replacing official heroism with ambiguity and irreverence.

Installation, Conceptualism, and Feminist Voices

In the 1990s, Czech art caught up with global trends in installation, video, and conceptual practices—mediums that had been stifled under communism. Artists began working with space, time, and audience engagement, often reflecting on history, gender, and trauma.

Kateřina Šedá, one of the most innovative artists of her generation, blends social work, performance, and documentary. Her projects—such as “There’s Nothing There” (2003), which activated an entire village to follow a synchronized schedule—challenge notions of community, routine, and meaning. Šedá’s work exemplifies relational aesthetics, turning everyday life into art.

Eva Koťátková, known for her psychologically charged installations and sculptures, explores the constraints of systems—educational, familial, bureaucratic—on the body and mind. Her constructions evoke both fairy tales and institutional control, bridging the personal and political.

Feminist and queer themes, long marginalized in Czech art discourse, gained visibility during this period. Artists like Lenka Klodová, Barbora Klímová, and Mark Ther began to explore sexuality, identity, and body politics, often in tension with more conservative strands of Czech society. Their work brought new urgency to questions of representation and inclusion.

Postmodern Historicism and the Weight of the Past

The post-1989 period also prompted a reconsideration of the Czech 20th-century legacy—especially the traumas of Nazism, communism, and national mythologies. Artists engaged in acts of memory excavation, often using found objects, archival material, or public interventions to critique selective remembrance.

One example is Jiří David’s 2002 installation “Heart for Václav Havel”, a giant illuminated heart on Prague Castle. Though widely embraced as a symbol of love and unity, the piece also sparked debate about sentimentality, political spectacle, and the role of art in public space.

Other artists used irony and pastiche to comment on the aesthetic residues of the communist period. The reuse of Brutalist architecture, Soviet iconography, and propaganda tropes became common in postmodern painting and video art—sometimes as critique, sometimes as nostalgic appropriation.

Photography and New Documentary

Czech photography also found new vitality, building on its long tradition of surrealism and reportage. Photographers like Jindřich Štreit, who had documented rural life under communism with quiet dignity, now addressed themes of poverty, exclusion, and post-industrial decay.

A younger generation embraced staged photography and video art, often influenced by cinema and theater. Tereza Vlčková’s dreamlike portraits and Lukáš Jasanský and Martin Polák’s conceptual photo-series exemplified a new approach: at once aesthetic and analytical, deeply embedded in the social fabric of post-communist reality.

Toward the 21st Century: New Institutions and Global Platforms

By the early 2000s, Czech contemporary art had established a strong institutional presence. The DOX Centre for Contemporary Art opened in Prague in 2008, offering ambitious exhibitions of Czech and international artists. The Jindřich Chalupecký Award, named after the critical champion of Czech modernism, became a major platform for emerging artists under 35.

Czech artists increasingly participated in international biennales, fairs, and residencies. Yet they also wrestled with the challenge of maintaining local relevance amid global circulation. For some, postmodern irony gave way to a return to sincerity, craft, and narrative. Others leaned further into critical theory and transnational politics.

The post-1989 period, then, was not a clean slate—it was a complex negotiation with history, memory, and the pressures of globalization. Czech art in this era did not seek a single voice, but rather embraced multiplicity: of media, message, and meaning.

Contemporary Czech Art: Global Voices, Local Identities (2010s–Present)

In the early 21st century, Czech art has continued to evolve in both form and function, shaped by the forces of globalization, technology, and cultural memory. The landscape today is one of plurality and tension—between the international art market and domestic concerns, between radical experimentation and a renewed interest in tradition, between institutional authority and grassroots creativity.

No longer constrained by ideological boundaries, Czech artists now move freely across genres, disciplines, and national borders. Yet even as they exhibit at biennales or collaborate with international institutions, many retain a distinctly Czech sensibility: ironic, historically layered, and attentive to the politics of space, body, and language.

Shifting Themes: Identity, Memory, and Landscape

Contemporary Czech art frequently grapples with questions of identity and historical consciousness. Whether exploring post-socialist legacies, environmental degradation, or the politics of gender and migration, artists draw from both local experience and global discourse.

Adéla Součková, for example, uses drawing, installation, and performance to explore myth, ritual, and collective memory, often with a feminist perspective. Her work blends raw symbolism with refined technique, positioning her as a unique voice in the dialogue between past and present.

Tomáš Rafa, a Slovak-born artist working largely in the Czech Republic, documents far-right protests, refugee camps, and border conflicts through documentary video and public interventions. His New Nationalism in the Heart of Europe series engages with the rise of populism and xenophobia, challenging the viewer to confront uncomfortable realities.

The theme of landscape, long central in Czech art, has been reinterpreted through ecological and conceptual frameworks. Artists like Markéta Othová use photography and spatial arrangements to examine urban change, memory of place, and the ephemerality of environment. Others, such as Krištof Kintera, blend sculpture, electronics, and satire to critique consumerism and ecological collapse.

New Media and the Digital Turn

Contemporary Czech artists are increasingly fluent in digital technologies, video, and immersive installation. This trend aligns with global developments, but often carries a localized charge—reframing traditional subjects through contemporary tools.

The Lunchmeat Festival in Prague, blending audiovisual art and electronic music, exemplifies this merger of media arts and club culture. Visual collectives such as XYZ project and The Rodina operate at the intersection of graphic design, gaming, and performance, often questioning the aesthetics of control in digital space.

Meanwhile, artists like Jakub Nepraš explore the relationship between technology and biology, creating multimedia sculptures that pulse with artificial life, data flow, and systems theory. His work speaks to the Czech Republic’s long-standing interest in the technological sublime, from Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. to posthuman aesthetics.

Institutions, Education, and Art Infrastructure

The Czech art world has matured significantly since the 1990s. Contemporary art institutions, museums, and biennales now provide sustained platforms for both established and emerging voices.

- The DOX Centre for Contemporary Art continues to host large-scale thematic exhibitions, public programs, and international collaborations.

- MeetFactory, founded by David Černý, combines studio residencies, music, and theater in a cross-disciplinary environment.

- The Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (AVU) and Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (UMPRUM) remain the top training grounds, with faculty deeply engaged in both practice and theory.

A growing number of independent spaces, such as Berliner Model, Pragovka, and Galerie 35M2, promote experimental and critical practices outside of commercial pressures. These spaces often blur the line between art and activism, emphasizing process over product.

The Jindřich Chalupecký Award, still one of the most prestigious for young artists, has adapted to changing expectations by embracing multimedia, performance, and social practice.

Public Art and Political Provocation

Public art remains a potent arena for commentary and engagement. David Černý, still active and controversial, continues to create interventions that provoke dialogue—sometimes admiration, often outrage. His 2020 kinetic sculpture Head of Franz Kafka remains a landmark, literally reflecting the fragmented modern psyche in a mirrored, rotating bust.

Newer artists engage with urban space in more ephemeral ways, using projection, street performance, or subtle intervention. Collectives like PAF (Festival of Film Animation and Contemporary Art) in Olomouc push the boundaries of media art into public and online spaces.

The political charge of public art—especially in a society still negotiating the legacies of occupation, communism, and nationalism—remains strong. Monuments are reexamined, statues reinterpreted, and public memory constantly contested.

Challenges and Critiques

Despite these advances, contemporary Czech art faces challenges. Funding remains inconsistent, especially outside Prague. Commercial support is limited, and artists often rely on European grants or freelance income. Cultural policy debates frequently reflect broader political tensions, including disputes over national identity, LGBTQ+ rights, and immigration.

There is also an ongoing debate about the role of Czech art abroad. Some critics argue that Czech artists are overrepresented in global trends but underrepresented in the country’s own collective consciousness. Others contend that the most vital work is happening in off-center regions and community-based practices, away from the capital’s institutions.

Continuity and Invention

What defines contemporary Czech art is not a single style or ideology, but a restless, questioning spirit. Artists draw from a deep reservoir of historical experience, from Hussite rebellion to Baroque piety, from Cubist utopianism to underground resistance. These echoes of the past lend Czech art its particular sharpness—a capacity for irony, introspection, and formal innovation that remains both rooted and radically open.

Key Institutions, Museums, and Collectors

Czech art history is not only the story of individual artists and movements—it is also the story of the institutions that house, protect, and interpret the nation’s visual heritage. From medieval monasteries to modern museums, from aristocratic collectors to state-funded galleries, these entities have played a crucial role in defining what Czech art is, who sees it, and how it evolves.

Today, the Czech Republic maintains a robust and diverse network of museums, galleries, academies, and private collections that span its historical and contemporary legacy. These institutions serve both as cultural memory banks and as platforms for new creation.

National Gallery Prague (Národní galerie Praha)

The cornerstone of Czech art preservation and exhibition is the National Gallery Prague (NGP), one of the oldest and most significant public art institutions in Central Europe. Founded in 1796 by the Society of the Patriotic Friends of the Arts, the NGP has grown into a multi-venue institution housing collections from medieval altarpieces to contemporary installations.

Its key sites include:

- Trade Fair Palace (Veletržní palác): Dedicated to 19th–21st century art, this Functionalist building holds works by Kupka, Filla, Toyen, and major international artists such as Picasso, Klimt, and Schiele. It also hosts rotating exhibitions of global contemporary art.

- Schwarzenberg Palace: Focused on Baroque art, including Czech masters like Brandl and Škréta, alongside Central European painters and sculptors.

- Kinský Palace: Home to 19th-century art, particularly Romanticism, Realism, and the National Revival era.

- Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia: Specializes in Gothic and medieval art, featuring early Bohemian panel painting and sculpture.

NGP has faced challenges in recent years, including leadership turnover and debates over curatorial direction. Yet it remains the central institution for the display and scholarship of Czech art history.

Regional Museums and Galleries

Art institutions beyond Prague play a vital role in preserving local traditions and highlighting regional identities:

- Moravian Gallery in Brno (Moravská galerie): The second-largest art museum in the country, it offers extensive collections of visual arts, applied design, and architecture, including the Josef Hoffmann Museum and the Museum of Applied Arts. Brno’s role in the Functionalist and avant-garde movements makes this institution particularly important for 20th-century studies.

- Gallery of Modern Art in Hradec Králové and Gallery of the Central Bohemian Region (GASK): Both are known for innovative exhibitions and important holdings of modernist and contemporary art.

- Kampa Museum: Located on Prague’s Kampa Island, it is devoted to Central European modern art, particularly the works of the Czech exile community, and holds major pieces by František Kupka.

- Museum Kampa, supported by the Jan and Meda Mládek Foundation, reflects the post-communist revival of private cultural patronage and collects works banned or marginalized during the totalitarian period.

Academies and Education

The Czech Republic boasts two premier fine arts academies:

- Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (AVU): Established in 1799, AVU has produced generations of influential artists and thinkers. It remains central to contemporary painting, conceptual art, and theory.

- Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (UMPRUM): Founded in 1885, UMPRUM has shaped Czech design, architecture, and media art, integrating traditional techniques with cutting-edge experimentation.

These schools also function as cultural incubators, curating exhibitions, publishing research, and fostering international exchange.

The Role of Private Collectors and Philanthropy

Historically, Czech art was supported by the nobility and bourgeois elite—families like the Lobkowicz, Schwarzenberg, and Wallenstein dynasties amassed important collections of European and Bohemian art, some of which are still on view today in private palaces or foundations.

In the post-communist era, a new generation of private collectors and patrons emerged. Figures such as Meda Mládková (a key supporter of Kupka and postwar Czech modernism) and contemporary investors have played critical roles in filling gaps left by underfunded state institutions.

Private galleries such as Hunt Kastner, Drdova Gallery, and Galerie Václava Špály support emerging talent and link Czech artists with the global market.

Despite challenges, philanthropy has returned as a viable force in Czech cultural life, often partnering with municipalities, universities, and EU cultural initiatives.

Archives, Libraries, and Scholarship

In addition to exhibition spaces, Czech art history is supported by a robust infrastructure of archives and research institutions:

- The Institute of Art History (Akademie věd ČR) produces scholarly journals, catalogues, and historical research on Bohemian and Moravian art.

- The National Museum’s Library and Czech National Archives house invaluable documents, blueprints, and correspondence that underpin art historical study.

- Independent publishing houses and journals like Umění, Ateliér, and Flash Art CZ/SK provide forums for critical dialogue.

Cultural Diplomacy and International Presence

Czech cultural institutions have increasingly participated in international exhibitions and biennales, including the Venice Biennale, where the Czech Pavilion has featured artists such as Dominik Lang, Jiří David, and Stanislav Kolíbal.

The Czech Centers, a network of cultural diplomacy offices in cities like Berlin, Paris, New York, and Tokyo, promote Czech visual culture abroad, mounting exhibitions, artist residencies, and collaborative programs.

These efforts reflect a mature cultural ecosystem, one that honors the legacy of centuries of visual culture while engaging with the demands of the 21st century.

Conclusion: Echoes of History in the Czech Visual Imagination

From Paleolithic figurines to postmodern interventions, the visual culture of the Czech lands reveals a striking continuity of invention, resilience, and introspection. Across epochs of independence, occupation, empire, and revolution, Czech artists have consistently forged a path that engages with European movements while retaining a distinct voice—by turns mystical, rational, lyrical, ironic, and defiant.

Czech art is neither marginal nor peripheral. Though often situated outside the dominant centers of Western art history, it has repeatedly anticipated or paralleled major developments: Gothic refinement, Baroque theatricality, Cubist architecture, avant-garde abstraction, and conceptual rigor. More than once, Prague and Brno have been crucibles of innovation, where artists adapted international idioms into culturally specific expressions of national memory, moral questioning, and visual experimentation.

Thematic Currents: Endurance Through Change

One of the defining characteristics of Czech art is its ability to absorb rupture—to reflect historical trauma not by retreating into nostalgia or escapism, but by reframing the past through contemporary eyes. Whether in the altar paintings of the Hussite era, the allegories of the National Revival, or the conceptual works of the post-communist underground, Czech art has functioned as both a mirror and a critique of power.