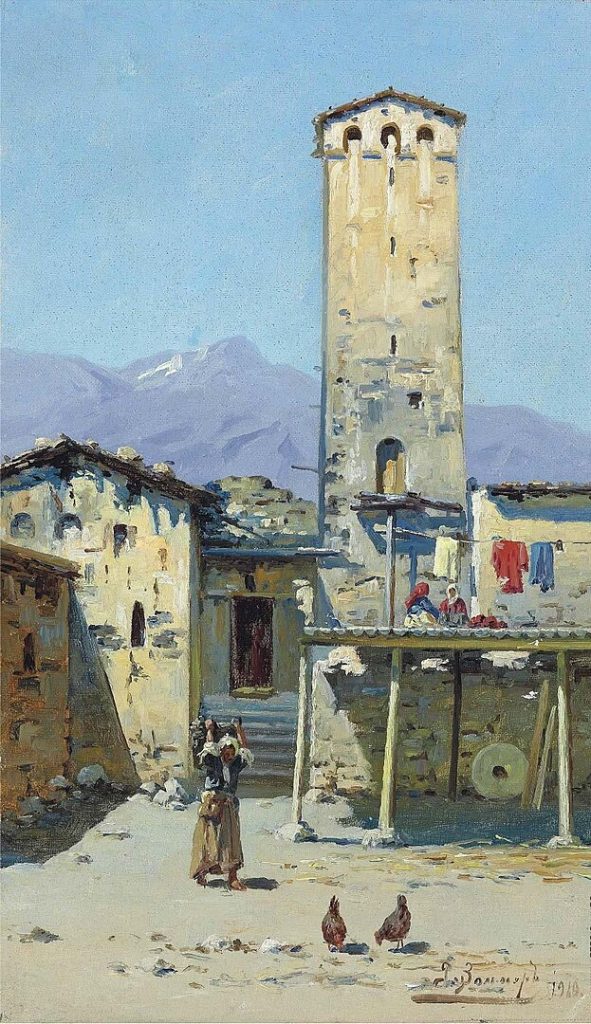

Tucked into the soaring peaks of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, the region of Svaneti in northwestern Georgia holds one of the most remarkable—and least altered—architectural traditions in the world. Isolated by rugged terrain and centuries of historical conflict, the people of Svaneti developed a unique style of fortified architecture that blends domestic life with defensive necessity. The most iconic expression of this is the Svan tower—tall, narrow, stone structures that dot the highland villages like medieval sentinels.

Dating as far back as the 9th century, and most commonly built between the 11th and 13th centuries, these towers served not only as family strongholds but also as symbols of independence, honor, and kinship. Most are attached to traditional machubi (stone houses), forming a compact residential-fortress unit capable of defending entire families during tribal conflicts or invasions.

The architecture of Svaneti is deeply rooted in the region’s history of feudal strife, clan-based society, and environmental isolation. These elements shaped a building tradition that is as practical as it is powerful. Walls are thick, windows are few, and everything is built to withstand time, siege, and the mountain climate.

Today, the villages of Upper Svaneti, particularly Mestia, Ushguli, and Chazhashi, form a living architectural museum. Recognized by UNESCO in 1996, the region has become a touchstone of Georgian heritage. Its stone towers, slate-roofed homes, and wooden balconies sit against a backdrop of glacial peaks, creating one of the most breathtaking architectural landscapes in Eurasia.

Historical Context: Geography, Clan Warfare, and Survival

The architectural character of Svaneti cannot be separated from its geography and history. This region lies between 3,000 and 6,000 feet above sea level, in the high Caucasus, bordered by Russia to the north and separated from the rest of Georgia by mountain passes. These passes are often snowbound in winter, which historically made Svaneti both isolated and independent.

For centuries, the Svans lived in small, family-based communities, known for their fierce independence and adherence to ancient customary laws (known as adat). Blood feuds, inter-clan conflicts, and threats from invading empires—Persians, Mongols, and Ottomans among them—led to a culture of self-reliance and local defense. Architecture was shaped directly by this context.

The earliest known towers date back to the 9th century, though most surviving examples were constructed between the 11th and 13th centuries, during Georgia’s medieval Golden Age. At that time, Svaneti functioned as both a frontier and a refuge. When Tbilisi and the eastern lowlands fell under Mongol or Persian rule, royal relics and religious icons were brought to Svaneti for safekeeping, elevating the region’s cultural prestige.

Each family clan (known as a “deda-kheoba”) built its own tower, usually adjacent to a home and auxiliary buildings like barns or storage sheds. These clusters formed tight-knit village compounds, often constructed on slopes or ridges for greater visibility and defense. The towers served not only military purposes but also symbolized a family’s honor, lineage, and territorial presence.

The Soviet period brought drastic change—roads were built, collectivization was imposed, and many towers fell into disrepair. But the architecture endured, and in the post-Soviet era, there’s been renewed pride and preservation. Today, these towers represent the soul of Svaneti: rugged, enduring, and deeply bound to the land.

The Svan Tower: Design, Materials, and Function

The signature feature of Svanetian architecture is the defensive tower—a tall, rectangular, tapering structure made entirely of locally quarried stone, usually schist or slate, with lime mortar. These towers typically stand 3 to 5 stories high, reaching 20 to 25 meters (65 to 80 feet). Their dimensions and structural details were finely tuned for defense, weather resistance, and long-term use.

The towers were built with slightly inclined walls, making them wider at the base than at the top. This subtle design not only added stability but also made them harder to scale. Most towers had one narrow entrance at ground level or slightly raised, accessible by ladder. Windows were slit-sized, allowing defenders to fire arrows or firearms while staying protected.

Inside, each floor was connected by ladders or trapdoors, often made of wood. The uppermost floor typically served as a watch post and featured parapets or machicolations—stone extensions with openings for dropping stones or hot liquid on attackers. The ceilings were vaulted in stone or covered with wooden beams, depending on the builder’s resources and skill.

Common Features of a Svan Tower:

- Height: 3–5 stories, 20–25 meters tall

- Material: Slate or schist with lime mortar

- Entrances: Single narrow door, sometimes elevated

- Floors: Interior wood or stone divisions, connected by ladders

- Parapets: Projecting battlements with firing or drop holes

- Windows: Small, few, and deeply recessed for defense

The towers were always built in connection to a dwelling—usually a machubi, or stone-and-wood house. This allowed families to move between domestic life and defensive readiness as needed. During peacetime, the tower was used for storage or as a guest space. In times of strife, it became a vertical fortress capable of resisting siege for days.

What makes these towers remarkable is their uniformity and variation. While built with similar methods, each reflects the skill, wealth, and personality of its builders. Some feature carved crosses, decorative corbels, or animal reliefs. Others remain plain but powerful, like pillars rising from the earth.

The Machubi and Residential Compounds

While the tower captures the imagination, it’s the machubi—the traditional Svan house—that provided daily shelter. These one-story structures were often built adjacent to or partially underneath the tower. They followed a rectangular floor plan, with thick stone walls and small windows, designed to retain heat during the frigid mountain winters.

The roof was usually made of heavy stone slabs or wooden beams covered with soil and turf. Inside, a central hearth or stove provided heat, and the family lived communally in a single large room. Livestock—especially cattle—were often kept in an adjacent bay or even within the same room during harsh winters, separated by a low partition wall. This arrangement conserved warmth and protected valuable animals.

The machubi was not lavish, but it was practical. Interiors were dark, warm, and low-ceilinged. Wooden chests, tools, and religious icons adorned the walls. Windows were few and small, both to conserve heat and discourage attack. The walls were often several feet thick, made from dry-laid stone or lime-mortared masonry.

Connected to the machubi was the refrigerator room (zabe) or grain storage area (noni), as well as an external kitchen used in summer. Wooden balconies or porches—added in later centuries—allowed families to dry herbs, meat, or laundry while taking in mountain views. These wooden elements are among the few expressive features in an otherwise utilitarian design.

The residential compound, including the tower, machubi, and outbuildings, formed a family stronghold—a miniature fortress for one or two related households. These compounds were arranged in loose clusters forming the village layout, usually on hillsides or ridgelines for defensive visibility and drainage.

Village Layout and Sacred Space

The village structure of Svaneti reflects a deep relationship between family, terrain, and spirituality. Unlike planned urban settlements, Svanetian villages evolved organically, adapting to the mountain contours and emphasizing defense, visibility, and self-sufficiency. Houses and towers are grouped into family compounds, and these clusters form loosely spaced hamlets connected by narrow paths rather than wide roads.

Because every household had its own tower, the village appears like a vertical stone forest—compact, defensible, and decentralized. There are no grand plazas or formal streets, only winding alleys and terraces. The land was divided among clans, and each group maintained its own communal pastures, orchards, and access to water sources. This spatial independence was essential during times of conflict, when one clan’s feud might not involve its neighbors.

At the heart of nearly every village is a church, often small and humble in size but richly painted inside. The majority of Svaneti’s churches date from between the 9th and 14th centuries and are constructed from local stone in simple basilica or single-nave plans. Despite their modest exteriors, the interiors are adorned with vivid frescoes, wooden iconostases, and metalwork—evidence of Svaneti’s role as a cultural refuge during Georgia’s medieval upheavals.

Churches were not only religious centers but also community gathering points. Feasts, festivals, and councils were held on adjacent lawns or under open-air shelters. Bells would call villagers together for both prayer and warning. Some villages also had cemeteries nearby, though traditional Svan burial often took place in isolated family plots on slopes or hilltops.

Villages like Ushguli—one of the highest permanently inhabited settlements in Europe—embody this layout perfectly. Its clusters of towers, modest churches, and stone houses stand in sharp contrast to the glacier-capped peak of Shkhara (5,201 meters), creating a landscape where architecture and nature speak the same bold, unforgiving language.

Construction Techniques and Local Materials

The architecture of Svaneti is as much a response to material limitations as to cultural ideals. Builders used what the land provided—primarily schist and slate, quarried from nearby hills, and occasionally limestone for finer detailing. Timber from high-altitude forests was used sparingly, often reserved for internal flooring, rafters, balconies, and joinery.

Dry stone masonry was common in older structures, with later buildings incorporating lime mortar as it became available. Walls were built thick—often up to 1.5 meters—to insulate interiors from extreme cold and add defensive strength. Roofs were covered in overlapping stone slabs, which resisted wind and snow but required steep pitches for drainage.

Foundations were often dug directly into the hillside. In some cases, the first floor of a machubi would be partially earth-sheltered, improving thermal stability. Floors were made of packed earth, stone flagging, or heavy wooden planks. Chimneys were rare; smoke from the hearth would vent through the roof beams or stone flues.

Windows were kept to a minimum and recessed deep into the wall to prevent heat loss and minimize vulnerability. Doors were often made of thick wood and reinforced with iron nails or fittings. In wealthier homes, carved lintels and doorposts offered modest decoration and local symbolism—sun motifs, crosses, and family signs.

Wood carving emerged as a local artistic expression. Balconies and porches often featured hand-carved railings and eaves, with floral, animal, and geometric designs. These wooden details softened the harshness of stone and connected even the simplest structures to the aesthetic traditions of Georgian folk art.

The entire building process was deeply communal. Family, neighbors, and clansmen worked together to construct towers and homes, sharing labor and materials. Even today, preservation projects in Svaneti often rely on traditional knowledge passed down through generations of builders.

UNESCO Recognition and Modern Preservation

The architectural treasures of Svaneti remained largely unknown to the outside world until the 20th century, when Soviet ethnographers and Georgian historians began documenting the region’s cultural wealth. In 1996, Upper Svaneti—particularly the village of Chazhashi within the Ushguli community—was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its exceptional preservation of medieval vernacular architecture.

UNESCO’s recognition highlighted both the value and vulnerability of the region. Climate change, depopulation, and modernization have posed serious threats to these ancient structures. Harsh winters, heavy snow loads, and seismic activity cause gradual degradation, while outmigration leaves many homes and towers abandoned or under-maintained.

The Georgian government, alongside international preservation organizations, has undertaken restoration programs focusing on structural stabilization, roof repair, and documentation. Some projects, particularly in Mestia, have sparked debate due to the introduction of modern materials and glass-heavy architecture that contrasts with the stone vernacular. However, others—like the meticulous work in Ushguli—have earned praise for preserving authenticity.

Efforts to preserve Svaneti’s architecture go hand-in-hand with reviving cultural traditions. Festivals, religious feasts, and rituals tied to these ancient buildings are being reintroduced to younger generations. Traditional tower-building techniques are being taught again, not just for tourism, but to sustain the knowledge of stone craftsmanship that defines the region.

Visitors today can stay in guesthouses built into centuries-old machubi, climb restored towers, and attend services in fresco-covered churches that have stood for a millennium. But preservation remains a race against time—and Svaneti’s architecture will endure only if its people remain committed to living with it, not just preserving it from afar.

Conclusion: A Fortress in the Clouds

The architecture of Svaneti is not grand in the classical sense—there are no golden domes, soaring cathedrals, or marble palaces. Instead, it is a deeply honest architecture: rugged, resilient, and intimately connected to the land and its people. Every stone tower, slate roof, and carved balcony tells the story of a community that built not just for beauty or comfort, but for survival and identity.

What sets Svanetian architecture apart is its unbroken continuity. While other medieval traditions were overwritten by Renaissance or modern styles, Svaneti’s structures remained rooted in ancient customs. Here, architecture wasn’t just about shelter—it was a tool of resistance, a form of storytelling, and a keeper of memory.

These stone towers, silhouetted against jagged Caucasus peaks, form one of the most compelling vernacular architectural landscapes in the world. They speak to a way of life that valued family honor, spiritual devotion, and coexistence with a formidable environment.

As modern roads and tourism bring Svaneti closer to the rest of the world, the challenge will be to preserve this unique heritage without diluting its spirit. The towers may stand as stone, but their true strength lies in the living culture they represent—a culture that, like its architecture, has weathered centuries of change without losing its soul.

Key Takeaways

- Svaneti’s architecture centers on medieval stone towers and machubi homes adapted to mountain life.

- Most towers were built between the 9th and 13th centuries as family fortresses and status symbols.

- Traditional homes were built from local stone, with turf or slate roofs and thick insulating walls.

- Village layouts reflect clan-based society, defensive needs, and religious centrality.

- UNESCO and Georgian preservation efforts are working to safeguard this rare architectural tradition.

FAQs

- What is the purpose of the Svan towers?

They were defensive structures used to protect families during conflict and symbolize clan honor. - How old are the towers in Svaneti?

Most date from the 11th to 13th centuries, though some may be as early as the 9th century. - Can visitors enter the towers today?

Yes, many have been restored and are accessible in villages like Mestia and Ushguli. - What materials are used in Svanetian architecture?

Slate or schist stone, lime mortar, timber for interiors, and slate for roofing. - Is Svaneti architecture still in use?

Yes, many traditional homes are inhabited, and preservation efforts are ongoing.