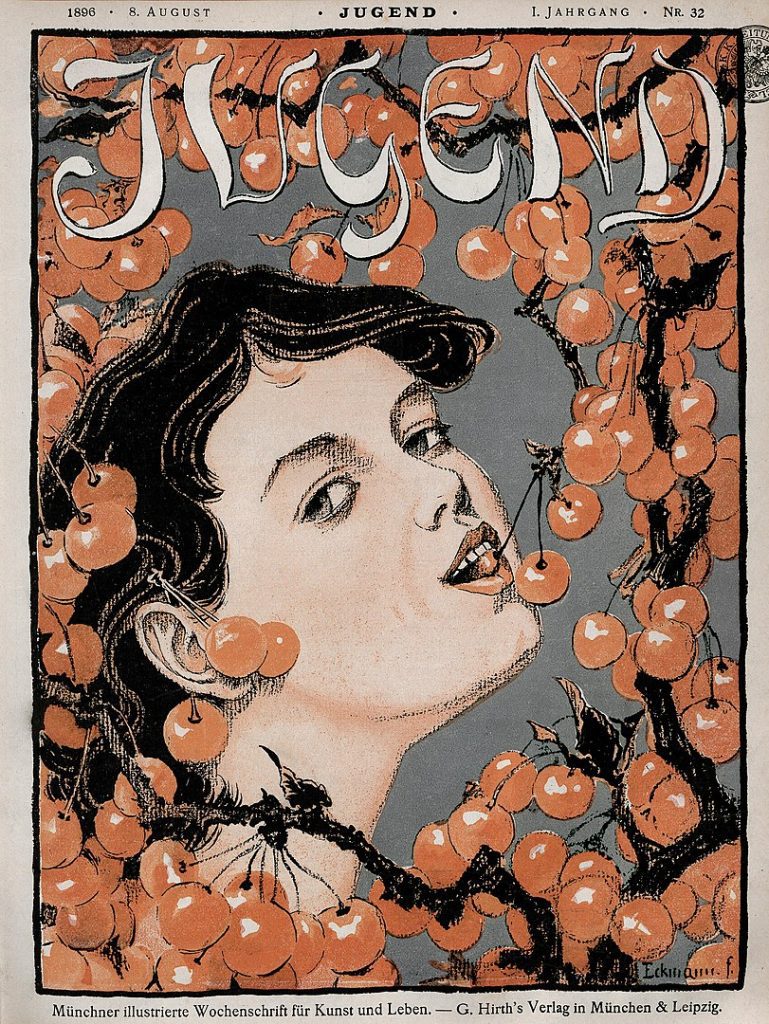

Jugendstil was Germany’s unique take on the Art Nouveau movement, emerging in the late 19th century and flourishing into the early 20th century. It was characterized by flowing lines, organic forms, and nature-inspired motifs that set it apart from previous artistic styles. The term “Jugendstil” translates to “Youth Style,” deriving its name from the influential German magazine Jugend, which played a crucial role in promoting this new aesthetic. More than just an art style, Jugendstil encompassed architecture, interior design, graphic arts, and even furniture, making it a comprehensive artistic movement.

The movement found its roots in a rejection of historicism and the industrial mass production that had defined 19th-century design. Artists and designers sought to create objects that were both beautiful and functional, emphasizing craftsmanship and unique artistic expression. Inspired by natural forms, Jugendstil incorporated elements such as floral patterns, curving lines, and asymmetry into its designs. This movement was part of a larger European trend that included France’s Art Nouveau, Austria’s Vienna Secession, and Britain’s Arts and Crafts movement.

Jugendstil’s influence extended beyond Germany, with artists and designers from Austria, Switzerland, and other German-speaking regions adopting its principles. The movement was particularly strong in cities such as Munich, Berlin, and Darmstadt, where artists collaborated to create stunning examples of Jugendstil art and architecture. It wasn’t just limited to painting or sculpture; it transformed entire cityscapes, influencing building facades, furniture, glasswork, and typography. By embracing both artistic beauty and modern design principles, Jugendstil laid the foundation for later movements such as Bauhaus and modernist industrial design.

Though Jugendstil thrived for only about two decades, it left an indelible mark on the world of art and architecture. The movement began to decline around 1910 as new artistic trends, such as functionalism and expressionism, took hold. However, its legacy can still be seen today in the preserved buildings, artwork, and decorative pieces that continue to inspire designers. This article explores the origins, key artists, architectural masterpieces, decline, and ongoing influence of Jugendstil in the modern world.

The Origins of Jugendstil

Jugendstil emerged in Germany during the 1890s as a reaction against the heavily ornamented historicist styles that had dominated the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution had led to the mass production of decorative objects, which many artists saw as soulless and uninspired. Influenced by the ideas of the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, German designers sought to reunite art with craftsmanship, creating aesthetically pleasing yet functional designs. This artistic rebellion was fueled by a growing desire to break away from traditional academic art and embrace more organic, free-flowing forms.

One of the most significant early influences on Jugendstil was Jugend magazine, founded in 1896 by Georg Hirth in Munich. The publication featured innovative graphic design, typography, and illustrations that embraced the curving, floral motifs typical of the new style. Jugend quickly became the central platform for promoting this movement, giving rise to its name and inspiring artists across Germany. Alongside Jugend, other publications such as Pan and Die Insel also contributed to spreading the ideals of Jugendstil through their avant-garde approach to visual art and design.

The movement drew inspiration from various artistic traditions, including Japanese woodblock prints, Rococo ornamentation, and Symbolism. Japonisme, which had captivated European artists since the mid-19th century, introduced asymmetry, flat color fields, and stylized nature-inspired forms to Jugendstil designers. Additionally, the fluid, dreamlike imagery of the Symbolist movement resonated with Jugendstil artists, who sought to create emotionally evocative works. These influences combined to form a distinctive style that emphasized elegance, movement, and the seamless integration of art into everyday life.

Two early pioneers of Jugendstil were Hermann Obrist and Otto Eckmann, whose works defined the movement’s aesthetic. Obrist, a Swiss-born artist, became famous for his Cyclamen textile design, which featured dynamic, swirling lines that would become a hallmark of Jugendstil. Eckmann, a painter and graphic designer, played a crucial role in shaping the movement’s typography, developing Eckmann-Schrift, one of the most famous Jugendstil typefaces. Their work helped establish Jugendstil as a revolutionary departure from traditional European design, setting the stage for its rapid expansion.

Key Artists and Their Works

Otto Eckmann (1865–1902) was one of the most influential figures in Jugendstil, particularly in the realm of graphic design and typography. Originally trained as a painter, Eckmann transitioned to applied arts, creating innovative designs that blended natural forms with modern aesthetics. His 1900 typeface, Eckmann-Schrift, became a defining element of Jugendstil, featuring elegant curves and organic shapes inspired by handwritten script. Eckmann’s work extended beyond typography, as he also designed book covers, posters, and ornamental patterns that embodied the movement’s artistic philosophy.

Peter Behrens (1868–1940) was another key figure in Jugendstil, although he later transitioned into modernist industrial design. In the late 1890s, Behrens produced Jugendstil-style posters, illustrations, and furniture that emphasized harmony between form and function. In 1907, he joined the German electrical company AEG, where he became one of the first designers to establish a corporate identity, paving the way for modern branding. His work at AEG, though more geometric than traditional Jugendstil, retained elements of the movement’s artistic vision, linking it to future developments in design.

Franz von Stuck (1863–1928) was a painter, sculptor, and architect who played a crucial role in blending Symbolism with Jugendstil. His paintings, such as The Sin (1893), featured dramatic compositions, sensual figures, and rich ornamentation, all hallmarks of the movement. Stuck also designed and built the Villa Stuck in Munich, an architectural masterpiece that reflected Jugendstil’s integration of art, architecture, and interior design. His work demonstrated how Jugendstil could be both decorative and deeply expressive, influencing later generations of artists and designers.

Richard Riemerschmid (1868–1957) was a leading Jugendstil furniture designer, known for his elegant yet functional pieces. Unlike earlier ornate furniture styles, Riemerschmid’s designs emphasized clean lines and handcrafted details, aligning with the movement’s ideals of uniting art and utility. His work in interior design, including his contributions to the 1906 Darmstadt Artists’ Colony, showcased how Jugendstil extended beyond painting and sculpture into everyday living spaces. Riemerschmid’s influence persisted well into the 20th century, as his emphasis on simplicity and craftsmanship foreshadowed the principles of modernist design.

Jugendstil in Architecture and Design

Jugendstil had a profound impact on architecture and interior design, transforming cityscapes and living spaces across Germany and beyond. Architects sought to break away from historicist styles, incorporating fluid, organic forms that mimicked nature. Facades featured curving lines, floral patterns, and asymmetrical compositions, creating a dynamic, almost dreamlike aesthetic. This approach extended to interiors as well, where furniture, stained glass, and decorative elements were seamlessly integrated into a unified artistic vision.

One of the most important architects of Jugendstil was August Endell (1871–1925), known for his innovative and expressive designs. His most famous work, the Elvira Studio in Munich, completed in 1898, showcased elaborate swirling patterns on its facade, resembling ocean waves. Endell’s designs emphasized movement and ornamentation, rejecting traditional rectangular forms in favor of fluidity. Though the studio was unfortunately destroyed during World War II, its photographs and surviving designs continue to inspire architects and designers today.

Another significant figure in Jugendstil architecture was Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867–1908), who played a major role in designing the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony. Established in 1899 under the patronage of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse, this artists’ community became a hub for Jugendstil experimentation. Olbrich’s Wedding Tower (1908), with its striking geometric forms and decorative elements, remains one of the most iconic Jugendstil buildings. The colony as a whole was designed as a total work of art, blending architecture, furniture, and landscape design into a cohesive artistic environment.

Jugendstil’s influence extended beyond architecture into furniture and decorative arts, where it emphasized craftsmanship and artistic integrity. Richard Riemerschmid created furniture that combined curved lines with functional simplicity, reflecting the movement’s ideals of beauty and utility. Glasswork and ceramics were also transformed by Jugendstil, with Ludwig Moser’s glass designs featuring delicate floral engravings and Art Nouveau-inspired shapes. Whether in buildings or interior furnishings, Jugendstil sought to surround individuals with art, making everyday life an immersive aesthetic experience.

The Decline and Transformation of Jugendstil

By the early 1910s, Jugendstil began to fade as artistic tastes and social conditions changed. One of the primary reasons for its decline was the rise of modernism, which prioritized functionality and minimalism over decoration. Movements such as the Deutscher Werkbund, founded in 1907, emphasized industrial efficiency and rejected the elaborate ornamentation of Jugendstil. As a result, many architects and designers who had previously embraced Jugendstil shifted towards more geometric and restrained styles.

World War I (1914–1918) further contributed to Jugendstil’s decline, as economic hardship made the production of handcrafted, ornate designs less viable. The war devastated Europe’s economy, and after 1918, there was a growing demand for practical, affordable, and mass-produced goods. The idealism of Jugendstil, which sought to blend art with craftsmanship, was no longer feasible in a world increasingly driven by industry and mass production. As a result, the movement faded, making way for new artistic directions.

One of the movements that emerged from Jugendstil’s decline was Bauhaus, founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius. While Bauhaus retained some of Jugendstil’s emphasis on unifying art and design, it rejected ornamentation in favor of simplicity and industrial production. Bauhaus architects and designers favored clean lines, functional forms, and minimal decoration, a stark contrast to the elaborate curves and floral motifs of Jugendstil. This transition marked a fundamental shift in design philosophy, as the art world moved towards modernist principles.

Despite its decline, Jugendstil did not disappear entirely; instead, it evolved and left lasting influences on later artistic movements. Elements of Jugendstil can be seen in Art Deco, which emerged in the 1920s with its combination of luxury, craftsmanship, and stylized forms. Additionally, contemporary designers continue to reference Jugendstil motifs, particularly in graphic design, typography, and decorative arts. Though its time in the spotlight was brief, Jugendstil’s emphasis on integrating art into everyday life remains a guiding principle in modern design.

Jugendstil’s Influence on Modern Art and Design

Even though Jugendstil was largely replaced by modernist and functionalist design movements, its influence can still be seen in contemporary art and design. One of the areas where Jugendstil had a lasting impact is graphic design, particularly in typography and branding. The curvilinear lettering and organic motifs developed by Jugendstil designers paved the way for expressive and artistic typography in modern advertising. The concept of a unified corporate identity, pioneered by Peter Behrens at AEG, remains a key principle in branding today.

Jugendstil also influenced mid-century modern furniture, particularly in Scandinavian design, which embraced organic forms and craftsmanship. Although Scandinavian modernism is more restrained than Jugendstil, it shares the movement’s belief that beauty and functionality should be seamlessly integrated. Designers such as Alvar Aalto incorporated fluid, nature-inspired shapes into their furniture, echoing the organic curves of Jugendstil. This demonstrates how Jugendstil’s principles continued to shape design long after the movement itself had faded.

Another area where Jugendstil’s influence is evident is contemporary illustration and poster art. Many modern illustrators draw inspiration from the whiplash curves and botanical motifs typical of Jugendstil, creating intricate and decorative compositions. Tattoo artists, interior decorators, and even fashion designers have also reinterpreted Jugendstil aesthetics for contemporary audiences. The movement’s emphasis on fluidity, elegance, and natural forms remains an enduring source of inspiration for visual artists today.

Finally, Jugendstil’s architectural legacy can still be found in preserved buildings and restoration projects. Many Jugendstil structures, such as those in Darmstadt, Vienna, and Munich, have been carefully maintained and continue to draw admiration from architects and historians. These buildings serve as a reminder of the movement’s innovative spirit and its attempt to make art an integral part of everyday life. Whether in typography, furniture, or architecture, Jugendstil’s impact is still alive in the 21st century.

Collecting and Preserving Jugendstil Today

Jugendstil objects remain highly sought after by collectors, with antique furniture, glassware, posters, and ceramics commanding high prices at auctions. Collectors appreciate the craftsmanship and artistry of Jugendstil pieces, which often feature delicate floral patterns and organic designs. Authentic Jugendstil furniture, particularly pieces by Richard Riemerschmid, can fetch significant sums due to their rarity and historical significance. Similarly, Moser glassware and Jugendstil-era posters, such as those designed by Otto Eckmann, are valuable collector’s items.

Museums across Europe showcase Jugendstil masterpieces, preserving them for future generations. The Leopold Museum in Vienna holds an extensive collection of Jugendstil artworks, particularly from Austrian artists like Gustav Klimt and Koloman Moser. In Germany, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg displays a rich selection of Jugendstil decorative arts, including furniture, textiles, and jewelry. Visitors to these institutions can explore the full breadth of Jugendstil’s artistic achievements and its role in shaping modern design.

Efforts to restore and maintain Jugendstil architecture have also gained momentum in recent decades. Many historic Jugendstil buildings, such as those in Darmstadt’s Artists’ Colony and Munich, have undergone careful preservation. Governments and private organizations recognize the cultural and artistic significance of these structures, ensuring that their intricate facades and interiors are not lost to time. By restoring these buildings, architects and historians help maintain Jugendstil’s legacy for future generations to admire.

For those interested in owning Jugendstil-inspired pieces, modern reproductions and reinterpretations are available. Contemporary designers continue to draw inspiration from Jugendstil’s aesthetic, creating furniture, wallpaper, and decorative items that reflect its distinctive style. Whether collecting antiques or incorporating Jugendstil motifs into modern interiors, art enthusiasts can continue to celebrate the beauty and innovation of this influential movement.

Key Takeaways

- Jugendstil was Germany’s version of Art Nouveau, emerging in the 1890s.

- The movement was heavily influenced by nature, Japanese art, and the Arts and Crafts movement.

- Key figures included Otto Eckmann, Peter Behrens, and Franz von Stuck.

- Jugendstil impacted architecture, typography, and industrial design.

- Although it declined around 1910, its influence continues in modern design.

FAQs

1. What does Jugendstil mean?

Jugendstil means “Youth Style” and was named after the magazine Jugend, which promoted the movement’s aesthetic.

2. Who were the main Jugendstil artists?

Key artists included Otto Eckmann, Peter Behrens, Franz von Stuck, and Richard Riemerschmid, among others.

3. How is Jugendstil different from Art Nouveau?

Jugendstil shares similarities with Art Nouveau but had a more structured, geometric quality compared to its French counterpart.

4. Where can I see Jugendstil architecture today?

Jugendstil architecture can be found in Munich, Darmstadt, and Vienna, with notable examples like the Elvira Studio and Villa Stuck.

5. What caused the decline of Jugendstil?

The movement declined due to the rise of modernism, World War I, and a shift toward functionalist design.

Meta Description

Explore Jugendstil, Germany’s Art Nouveau movement, its origins, key artists, architecture, and lasting influence on modern design.