Édouard Manet, born on January 23, 1832, in Paris, France, stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism, challenging the artistic conventions of his day with his innovative approach to painting. Despite often being associated with the Impressionists, Manet maintained a distinct style that diverged from the movement’s foundational principles, even as he influenced its development and was influenced by its techniques. His work is characterized by a bold use of color, a modernist approach to subject matter, and a disregard for traditional perspective and modeling, which, in his time, sparked controversy but eventually earned him recognition as one of the forefathers of modern art.

Manet was born into an affluent and well-connected family. His father was a judge, and his mother was the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince. Despite his father’s wishes for him to pursue a career in law, Manet was drawn to art from an early age. After failing the entrance exam to the naval college, he began to pursue art more seriously, studying under Thomas Couture, a respected academic painter. Manet traveled extensively in Europe, particularly in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands, where he was influenced by the works of the Old Masters, especially Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, whose use of light and shadow would have a lasting impact on his work.

Good & Bad Publicity

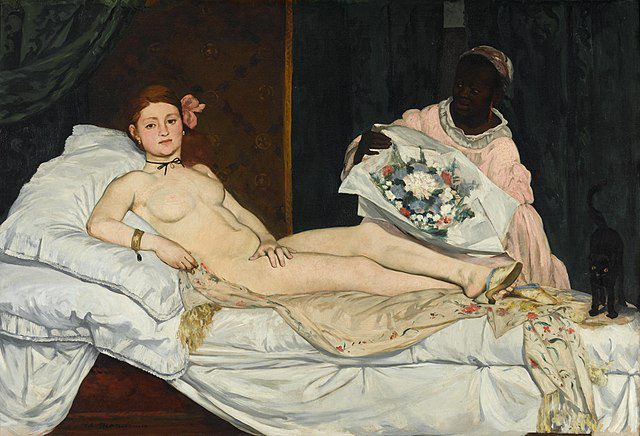

In the 1860s, Manet’s work began to attract attention, not all of it positive. His painting “The Luncheon on the Grass” (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe), exhibited in 1863 at the Salon des Refusés, caused a scandal. The juxtaposition of a nude woman with fully dressed men in a contemporary setting challenged traditional representations of the nude and the conventions of academic painting. This was followed by “Olympia” in 1865, a nude portrait that shocked the public and critics alike for its stark portrayal of a prostitute. These works, though controversial, underscored Manet’s disregard for classical norms and his interest in depicting modern life.

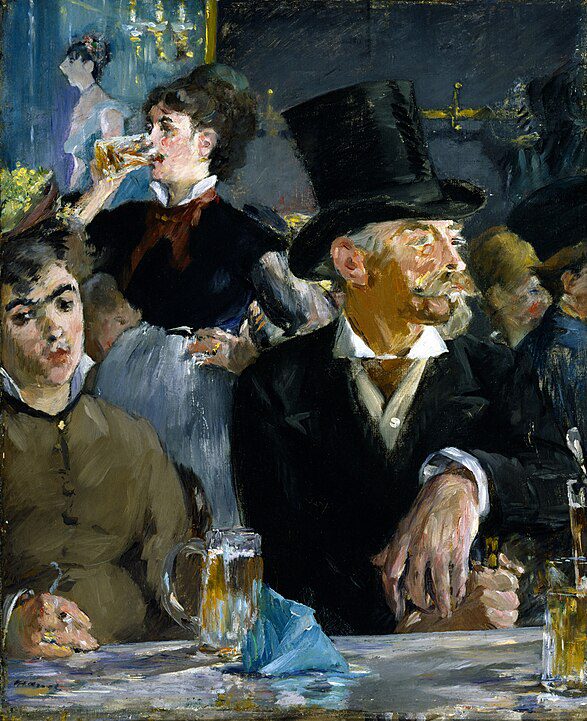

Manet’s style evolved over the years, yet he always sought to capture the essence of his subjects with swift brushstrokes and a keen sense of light. His café scenes, such as “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère” (1882), are celebrated for their vibrant portrayal of Parisian social life and innovative use of perspective. Despite his influence on the Impressionists, Manet never fully embraced their dedication to painting en plein air (outdoors) or their fascination with the effects of light on the landscape. Instead, he remained committed to studio work and the portrayal of urban life.

Fighting for Acceptance

Throughout his career, Manet struggled for acceptance in the official art circles of Paris. Although he aspired to success at the Salon—the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts—he was frequently met with rejection and criticism. However, by the 1870s and 1880s, his work began to gain more recognition and acceptance, culminating in receiving the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest order of merit, in 1881.

Manet’s health began to decline in the late 1870s, and he died in Paris on April 30, 1883, at the age of 51. His last works, which include flower still lifes and small-scale portraits, reveal a softer approach in his painting style, showcasing his versatility and continued innovation until the end of his life.

Manet’s legacy is profound. By breaking away from traditional techniques and subjects, he opened the door for future generations of artists to explore new perspectives and themes. His work laid the groundwork for the Impressionist movement and continued to influence artists well into the 20th century. Today, Manet is celebrated as a foundational figure in the history of modern art, a rebel who challenged the status quo and in doing so, forever changed the course of art history. His paintings, once controversial, are now revered for their bold experimentation and pivotal role in the evolution of modern painting.