Anders Zorn was born on February 18, 1860, in the village of Mora, Dalarna County, Sweden. He was the illegitimate son of Grudd Anna Andersdotter, a local peasant woman, and Leonard Zorn, a German brewer from Bavaria who never played an active role in his life. Zorn was raised by his maternal grandparents in rural Mora, where he displayed an early talent for drawing and carving. By the age of 12, he was already showing promise as an artist, impressing locals with his ability to capture likenesses.

In 1875, at the age of 15, Zorn entered the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm, where he received a rigorous classical education in painting and sculpture. His professors quickly recognized his natural skill and attention to detail, especially in watercolors. Zorn’s early training included anatomical studies, figure drawing, and the fundamentals of European academic art. His time in Stockholm helped him transition from provincial talent to a serious, classically trained artist.

From Mora to Stockholm – Zorn’s Formative Years

During these years, Zorn developed a disciplined work ethic and began exploring themes that would later define his career—portraiture, rural life, and light. His first major breakthrough came in 1880 with the watercolor painting In Mourning, which received critical acclaim for its realism and emotional depth. Zorn graduated in 1881, already receiving commissions from Stockholm’s upper class. Despite this early success, he remained deeply connected to Mora and often returned home between assignments.

This dual identity—provincial roots and cosmopolitan training—would become a recurring theme in Zorn’s life and work. He was as comfortable painting royalty in European capitals as he was depicting Swedish peasants by the riverbanks. His early years laid the foundation for a career that would straddle multiple cultures and social classes. By the early 1880s, Zorn had begun to travel abroad, seeking both inspiration and patrons.

Artistic Breakthrough and European Travels

Zorn’s travels across Europe were essential to his development as an internationally recognized painter. After his graduation, he toured England, France, and Spain, soaking in the latest trends in European painting while refining his own style. His technical proficiency, especially in watercolor, set him apart from many of his contemporaries. By 1882, his piece The Thorn further established his reputation for emotional depth and technical brilliance.

His travels allowed him to meet influential art dealers and patrons who introduced him to elite social circles in Paris and London. During this period, he became known for his genre scenes and lifelike portraits. Unlike many Swedish artists of his time, Zorn did not settle in one cultural hub but instead maintained a broad network of contacts throughout Europe. These years were crucial in helping him develop a signature style based on direct observation, warm natural light, and energetic brushwork.

Zorn’s Emergence on the International Scene

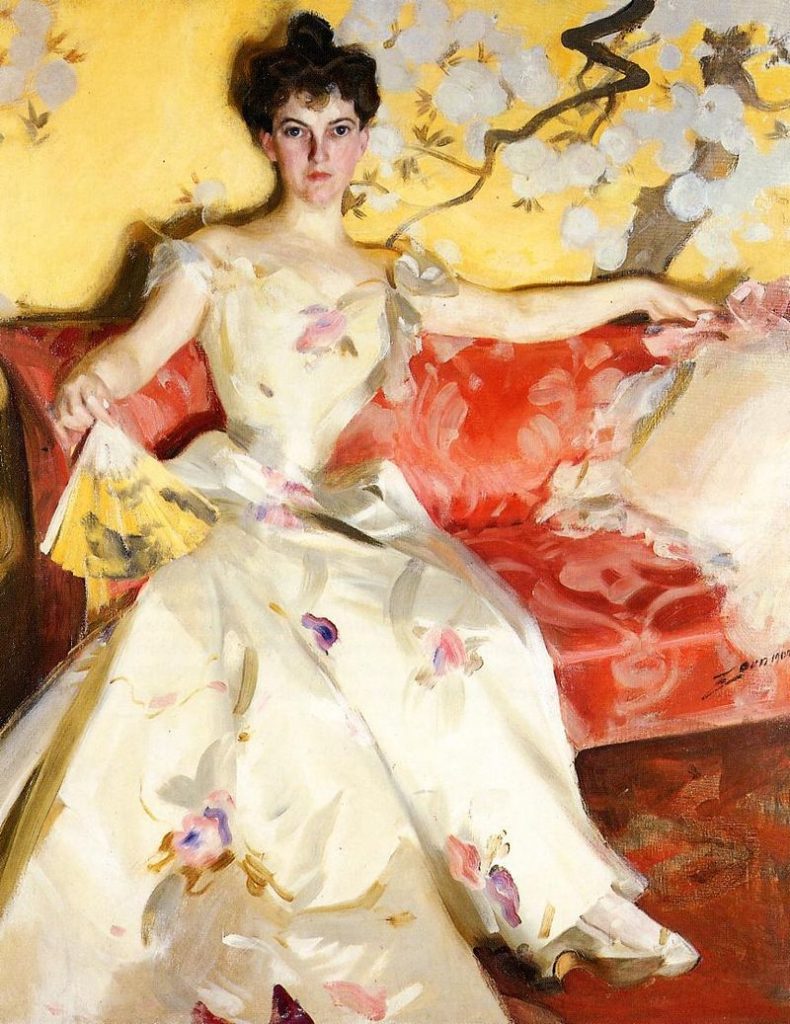

A pivotal moment in Zorn’s life came in 1885 when he married Emma Lamm, a woman from a wealthy and cultured Jewish family in Stockholm. Emma’s social connections proved invaluable to Zorn’s career, opening doors to affluent clients across Europe. Together, they lived for extended periods in London, Paris, and Madrid, where Zorn continued to attract commissions from aristocrats and industrial magnates. Their marriage was also a true partnership—Emma managed his finances, helped arrange exhibitions, and accompanied him on many of his travels.

By the late 1880s, Zorn had emerged as one of Europe’s most in-demand portrait painters. His reputation spread quickly, helped by exhibitions in Paris and London. He received invitations to show his work at major salons and international expos. While his style was realist, it had a modern, fluid quality that appealed to contemporary tastes—distinct from the stiffer academic tradition of the time.

Mastery of Watercolor and Oil

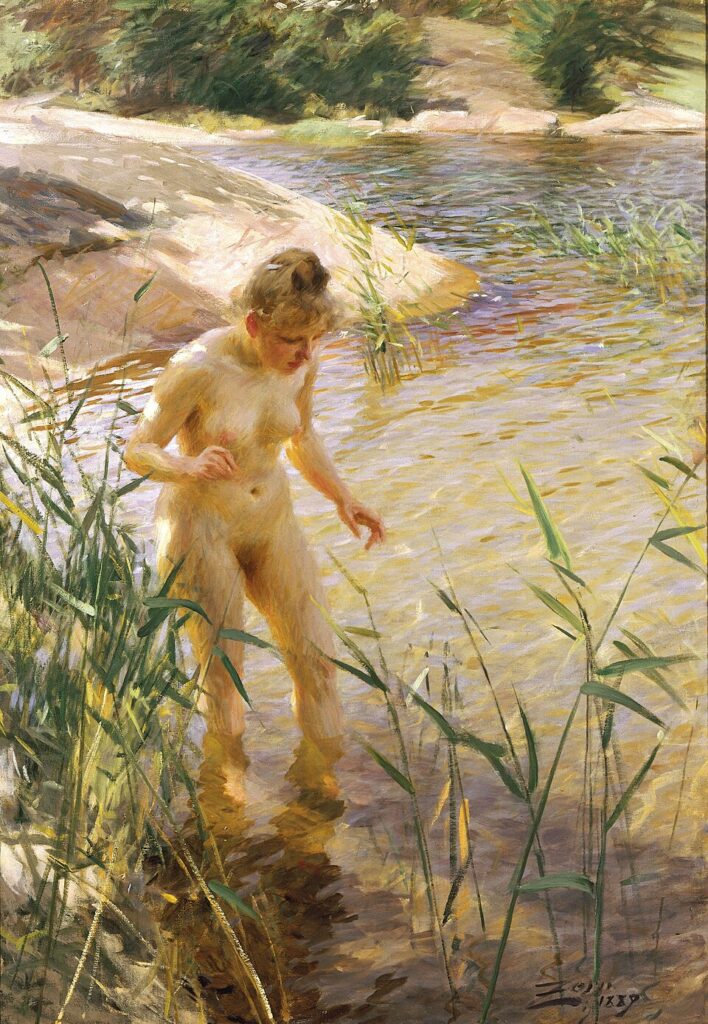

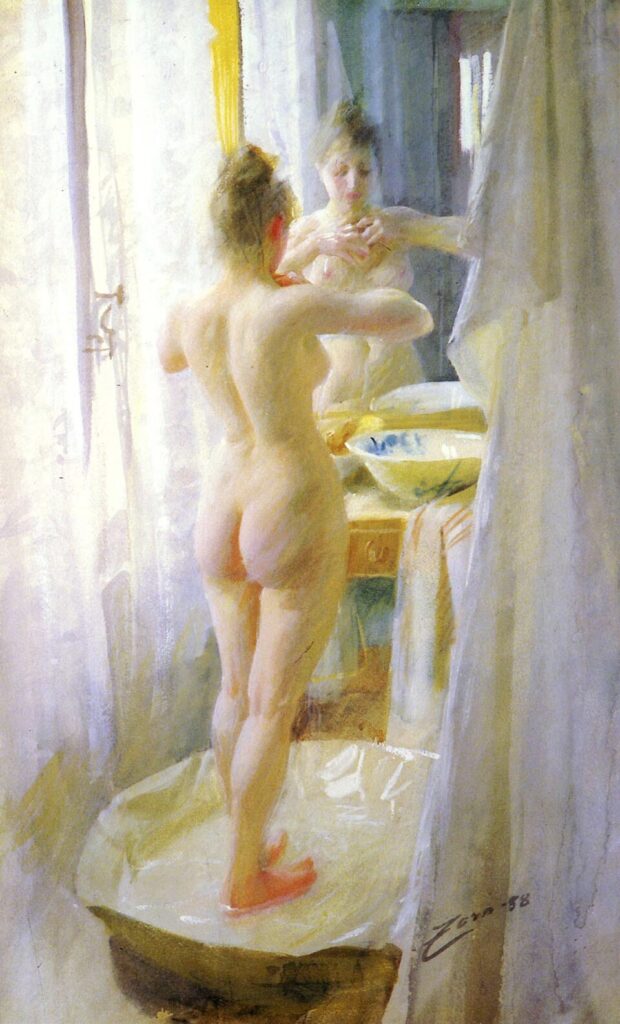

Zorn’s command of both watercolor and oil painting distinguished him as a versatile and masterful technician. His early fame was built on watercolors, a medium in which he could capture fleeting light, facial expression, and atmosphere with astonishing clarity. He often painted scenes of daily life, fishermen, and women bathing, using sunlight as a compositional element. This command of light led to comparisons with other great Impressionist and post-Impressionist painters, although Zorn maintained a realist approach.

By the 1890s, Zorn had shifted more toward oil painting, which allowed for a richer texture and more permanent effects. His portraits from this era—such as Emma Zorn (1887) and Omnibus (1892)—showcase his ability to combine realism with psychological insight. Zorn’s brushwork became looser, more expressive, yet never careless. His technique was described by critics as “painting with light,” and he often worked alla prima, completing paintings in a single session.

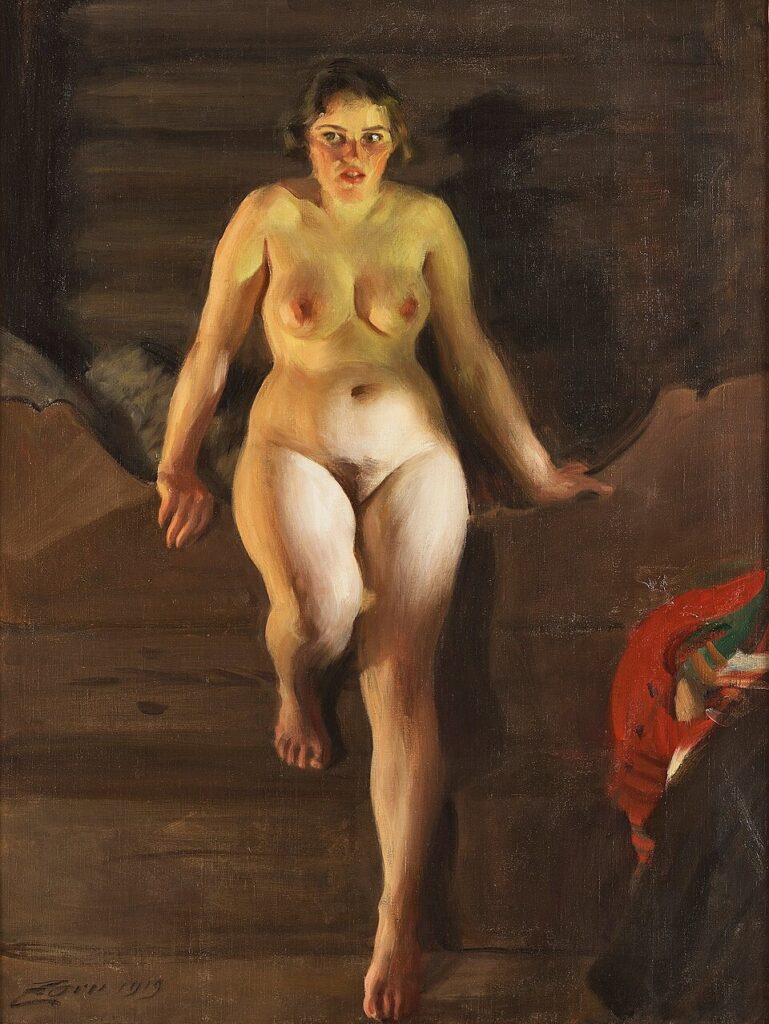

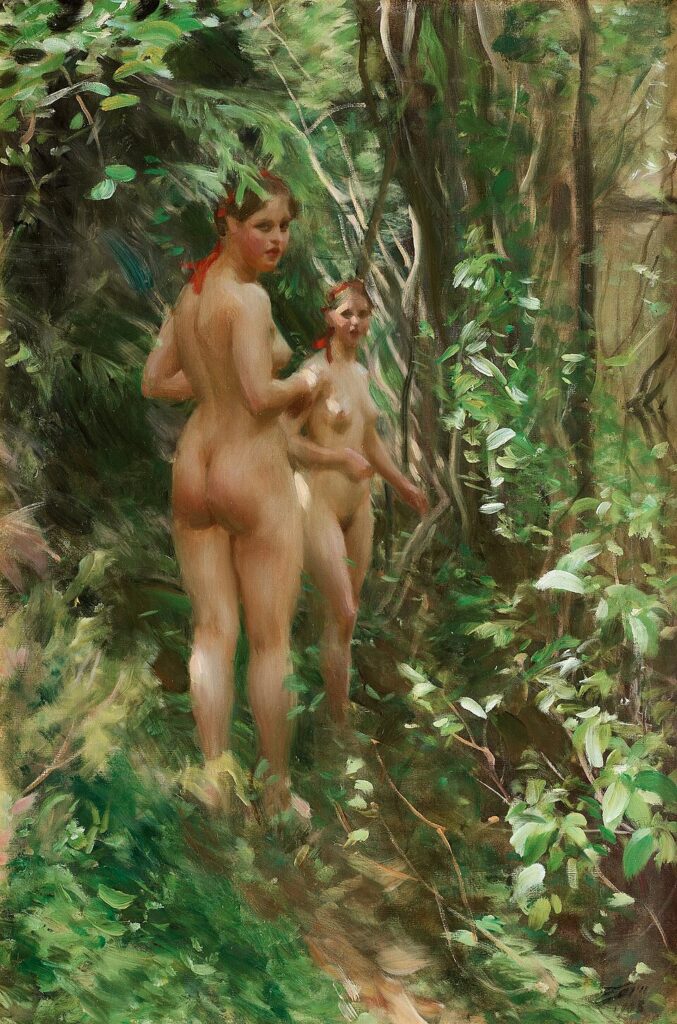

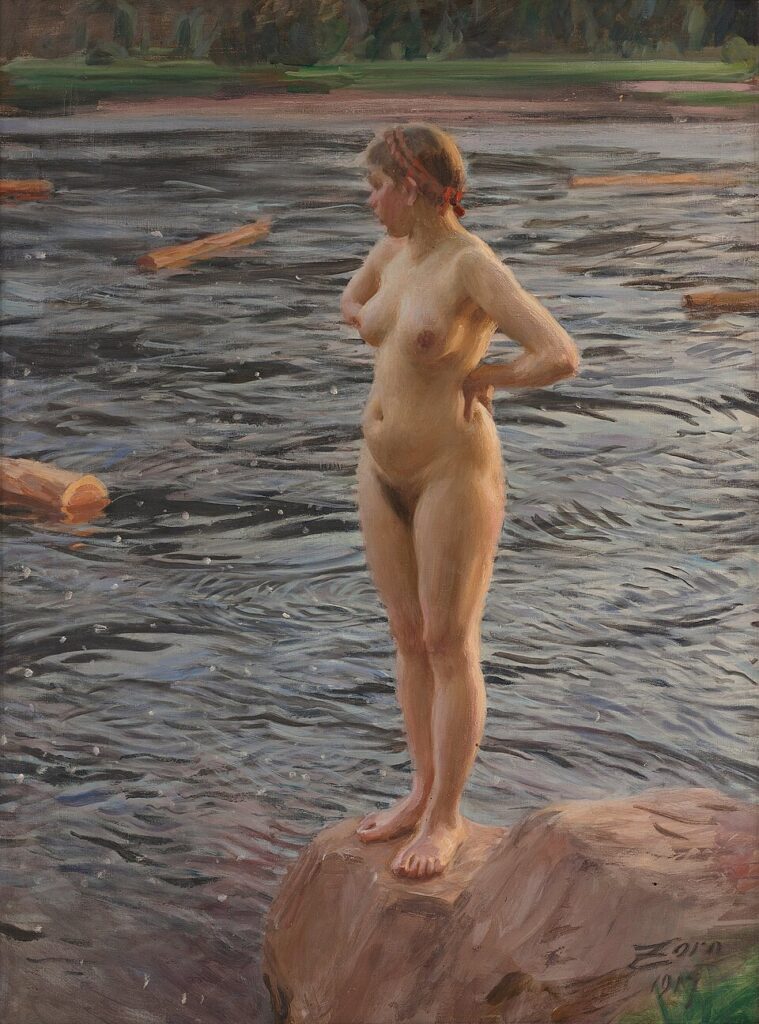

Technique, Light, and the Female Nude

One of Zorn’s most controversial and celebrated subjects was the female nude, especially in outdoor settings. He painted local women from Mora, typically posed in nature, using available sunlight to enhance the naturalism of their skin tones. Works like A Swim (1897) and Reflections (1894) reveal his fascination with the human form, rendered with honesty rather than idealization. Unlike the classical nudes of the past, Zorn’s women were robust, confident, and lifelike.

Zorn was often compared to John Singer Sargent and Joaquín Sorolla, both known for their vivid handling of paint and bold use of light. While all three shared similarities, Zorn’s palette was more restrained, focusing on grays, ochres, and warm flesh tones. His use of limited color range enhanced the mood of his scenes and allowed the viewer to focus on form and movement. These artistic choices solidified Zorn’s place in the upper ranks of turn-of-the-century painters.

Zorn in America – A Celebrity Portraitist

In the early 1890s, Zorn began making regular trips to the United States, where he quickly attracted the attention of America’s political and business elite. His first major American commission came in 1893, when he was invited to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. There, he exhibited alongside other prominent European artists and completed portraits of several wealthy Americans. His refined yet bold portraiture resonated with American tastes, especially among the new industrial class.

During his American visits, which spanned 1893 to 1896, Zorn painted some of the most powerful figures of the day. His subjects included President Grover Cleveland and the socialite Mrs. Potter Palmer. In 1905, he painted a now-iconic portrait of President Theodore Roosevelt, capturing the president’s energy and character with striking economy of means. This commission cemented Zorn’s reputation as one of the world’s premier portraitists.

Painting Presidents and the Elite

Zorn’s American patrons also included Isabella Stewart Gardner, one of the most influential art collectors in Boston, and Charles Deering, an industrialist and philanthropist. These relationships not only enriched him financially but gave him access to an extended network of commissions and exhibitions in the United States. His ability to balance European sophistication with a direct, accessible painting style made him especially appealing to American tastes.

Despite spending much of his time in Sweden and Europe, Zorn left a significant mark on the American art scene. He influenced portraiture trends among American painters, encouraging a freer, more expressive approach. His bold brushwork, casual poses, and naturalistic rendering of skin became a hallmark for others to emulate. By the end of his U.S. visits, he had firmly established a transatlantic legacy.

Life in Mora and National Identity

By the mid-1890s, Zorn and Emma decided to settle permanently in Mora, building a grand residence known as Zorngården. Completed in stages by 1910, the house blended Swedish folk design with modern comforts and served as a symbol of their commitment to national heritage. It included studios, guest rooms, and traditional Swedish interiors. Today, Zorngården stands as a museum, preserving Zorn’s personal and artistic legacy.

In Mora, Zorn immersed himself in preserving Swedish folk culture. He collected traditional costumes, musical instruments, and commissioned local musicians to perform and record their songs. Zorn saw these efforts not just as nostalgic but as patriotic, a means of strengthening Sweden’s national identity in an increasingly modernized Europe. He was also a staunch defender of traditional Swedish customs in architecture, education, and dress.

Embracing Swedish Folk Culture and Philanthropy

Zorn also gave generously to his community. He funded local schools, a public library, and even helped establish the local fire department. One of his enduring contributions was to sponsor scholarships for young artists and musicians from Mora, giving others the opportunities he once received. He viewed these acts as part of his duty to give back to the place that had shaped him.

His relationship with Emma was central throughout this period. Though they never had children, the couple poured their energy into cultural and charitable work. Emma’s financial acumen and social ties remained vital to Zorn’s success, even in their quieter years. Together, they curated a legacy that combined artistic excellence with civic duty and deep national pride.

Etching, Printmaking, and Artistic Legacy

Though best known for his paintings, Anders Zorn was also a master printmaker, particularly skilled in etching. He produced more than 290 etchings over his career, many of which are now prized collector’s items. His etched portraits capture a similar spontaneity and precision as his oil paintings, but with a stark, dramatic quality unique to the medium. The use of light and shadow in his etchings was especially effective, showing a strong command of chiaroscuro.

Among his most famous etchings are President Theodore Roosevelt (1905) and Self-Portrait with Model (1896). These works display his ability to suggest form and atmosphere with just a few confident lines. Etching also allowed Zorn to reach a broader audience, as prints could be distributed more widely than original canvases. This helped spread his fame beyond Europe and America, even into Russia and Japan.

Zorn’s Influence in Modern Printmaking

Contemporary artists such as James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent praised Zorn’s etchings for their directness and technical control. His innovations in drypoint and aquatint methods inspired a new generation of printmakers in both Europe and North America. He also played a role in elevating etching as a fine art medium during a time when it was often considered secondary to painting.

Today, Zorn’s printmaking is studied in art academies and collected by major museums, including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. His etchings remain benchmarks for technique and composition. His dual legacy in painting and printmaking places him among the most accomplished artists of his era. Zorn’s ability to work across mediums demonstrated his commitment to mastering every tool available to him.

Final Years and Enduring Reputation

In the final years of his life, Zorn continued to paint, though his health began to decline. By the late 1910s, he suffered from diabetes and exhaustion, though he remained creatively active. Despite reduced public appearances, he continued to support local causes and mentor young artists. Anders Zorn died on August 22, 1920, in Mora, at the age of 60.

At the time of his death, Zorn left behind more than 550 paintings, 300 etchings, and hundreds of drawings and sketches. His widow Emma worked to preserve his legacy, donating his personal collection and home to the Swedish people. In 1939, she established the Zorn Museum in Mora, which remains one of Sweden’s most visited cultural landmarks. The museum includes both his artworks and the carefully preserved interiors of Zorngården.

Death, Memorials, and the Ongoing Zorn Myth

Zorn’s reputation has endured long after his death. Major retrospectives have been held in Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum, the Petit Palais in Paris, and the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco. These exhibitions have helped introduce his work to new audiences and reexamine his importance in art history. In recent years, scholars have explored his role in bridging Realism with emerging trends in Nordic Modernism.

Zorn is remembered not only for his technical brilliance but also for his unapologetic embrace of national heritage and classical beauty. In a time of rapid cultural change, he remained committed to realism, tradition, and civic virtue. His contributions to both Swedish and international art endure in private collections, museums, and textbooks. Few artists have matched his ability to work across cultures while remaining deeply rooted in their homeland.

Key Takeaways

- Anders Zorn was born in Mora, Sweden, in 1860 and studied at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts.

- He gained fame for his watercolors, oil portraits, and vivid depictions of the female nude.

- Zorn painted U.S. Presidents and social elites during his American visits in the 1890s.

- He supported Swedish folk traditions and founded cultural institutions in Mora.

- Zorn left a legacy of over 550 paintings and nearly 300 etchings, many of which are held in top museums.

FAQs

- Where was Anders Zorn born?

He was born in Mora, Sweden, on February 18, 1860. - Who did Anders Zorn marry?

He married Emma Lamm in 1885, a key figure in his career and legacy. - Which U.S. presidents did Zorn paint?

He painted portraits of Grover Cleveland, William H. Taft, and Theodore Roosevelt. - What was Zorn known for artistically?

Zorn was celebrated for his portraits, watercolors, nudes, and etchings. - When did Anders Zorn die?

He passed away on August 22, 1920, in Mora, Sweden.