Jean-Léon Gérôme was born on May 11, 1824, in the provincial town of Vesoul, located in the Haute-Saône region of eastern France. His father, a skilled goldsmith, ensured the family lived in modest comfort, and young Jean-Léon grew up surrounded by careful craftsmanship and precision. From an early age, he showed signs of artistic talent, often drawing animals and figures with striking clarity. Although his hometown was far from the bustling Paris art world, Gérôme’s passion for visual expression was already unmistakable.

By his teenage years, it became clear to his family that he needed formal training to grow as an artist. In the early 1840s, Gérôme convinced his parents to let him move to Paris, which was then the artistic capital of Europe. Paris offered exposure to salons, galleries, and rigorous instruction—an ideal environment for any aspiring artist. His relocation to the city marked the beginning of a long and transformative journey in both painting and sculpture.

A Childhood in Vesoul

Despite early setbacks, Gérôme’s commitment to becoming an artist remained unwavering. He submitted early works to local exhibitions, gaining some recognition for his skillful line and attention to detail. Unlike many contemporaries who began with Romantic styles, Gérôme leaned early toward clear forms and academic restraint. This disciplined approach would become his signature and remain with him throughout his life.

The roots of Gérôme’s mature style can be traced to his early love of classical antiquity and structured beauty. These influences would later shape his compositions and subjects, especially as he rose in prominence in the mid-19th century. Though born in a small town, Gérôme’s ambitions were never provincial. By stepping into Paris at a critical moment in his youth, he aligned himself with a tradition of mastery that defined his entire career.

Education and Classical Foundations

Once in Paris, Gérôme sought instruction from established masters who were part of the Academic tradition. In 1843, he joined the studio of Paul Delaroche, a well-known historical painter and a leading figure of the French Academy. Delaroche believed in meticulous draftsmanship and narrative clarity—ideals that deeply resonated with Gérôme. Under Delaroche’s guidance, he developed strong foundational skills and began to think seriously about historical subjects.

In 1844, Delaroche took Gérôme and a group of students on a grand tour of Italy. The young artist spent time studying classical ruins, Roman sculptures, and Renaissance masterpieces in Florence, Rome, and Naples. These travels solidified Gérôme’s love of antiquity and fed his imagination for historical settings and costume accuracy. He sketched avidly and absorbed lessons that would appear again and again in his major works. The Italian sojourn was more than a student trip—it was a turning point.

Mentored by Masters

Following his return to Paris, Gérôme briefly studied under Charles Gleyre, another respected teacher known for guiding disciplined draftsmen. Soon after, he was admitted to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the elite art school of France. Entry into this institution marked a major milestone, signifying Gérôme’s acceptance into the highest tier of academic training. At the École, he honed his skills in figure drawing, anatomy, and historical composition.

While many artists of the time dabbled in multiple styles, Gérôme remained loyal to the academic method. He believed art should be clear, intelligible, and refined—values that were reinforced at the École. His education was not merely about technique, but also about moral and intellectual rigor. These years laid the technical and philosophical foundation for Gérôme’s entire artistic identity.

Breakthrough Success and the Prix de Rome

Gérôme’s early promise turned to public success in 1847 when he exhibited “The Cock Fight” (Jeune Grec faisant battre des coqs) at the Paris Salon. The painting, completed in 1846, was a vivid, neoclassical scene of two young men watching a pair of fighting roosters. The composition was tight, the anatomy precise, and the mood contemplative. The painting won a third-class medal and brought Gérôme to the attention of critics and collectors alike.

Following this early triumph, Gérôme sought to secure the coveted Prix de Rome, a scholarship that sent top students to study in Italy. He entered the competition in 1847 but failed, a significant disappointment at the time. However, this rejection became a blessing in disguise. Rather than follow the well-worn path to Rome, Gérôme forged his own route, focusing on history painting with a unique blend of accuracy and theatricality.

Debut at the Salon of 1847

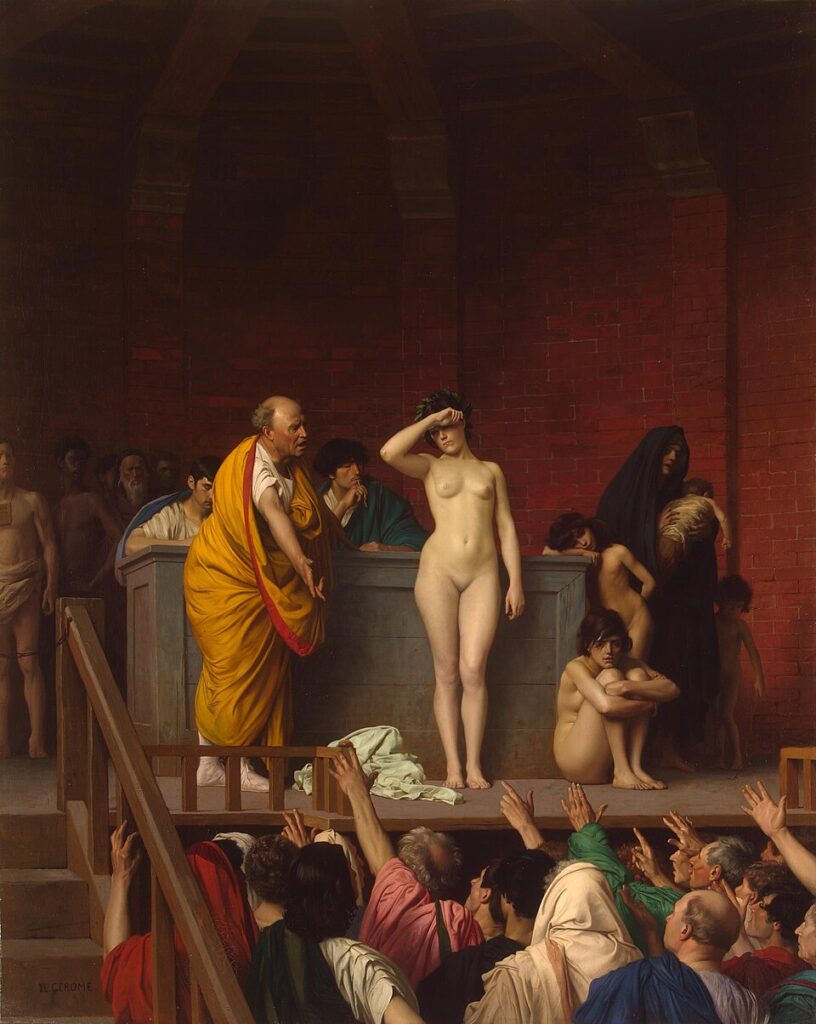

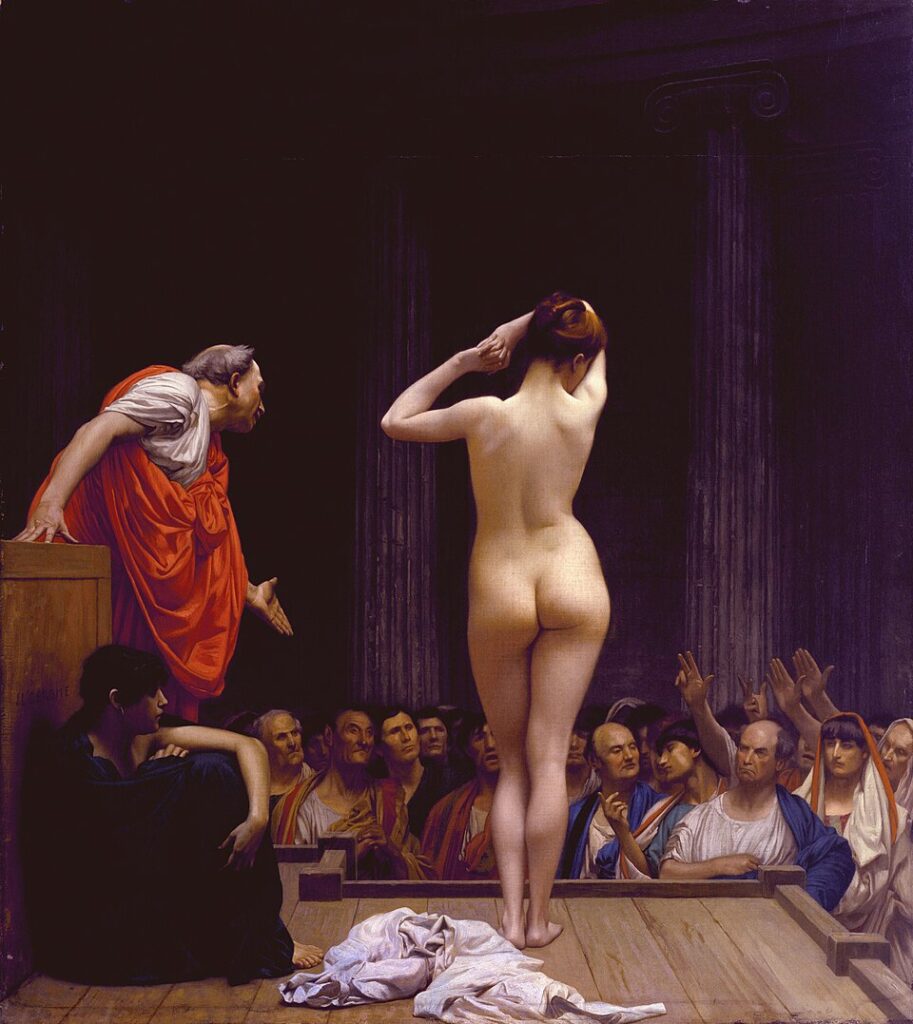

Despite missing out on the Prix de Rome, Gérôme continued to produce successful works throughout the 1850s. His paintings during this period explored themes from Greek history, biblical episodes, and French classical literature. His Neo-Grec style—a blend of archaeological detail and romantic storytelling—resonated strongly with the public. Works like “Phryne before the Areopagus” (1861) demonstrated both technical excellence and dramatic flair.

His reputation grew quickly, and commissions poured in from government patrons and private collectors. Gérôme’s commercial appeal was strengthened by his association with the art dealer Adolphe Goupil, who would later become his father-in-law. By his mid-thirties, he was not only established but had become one of the leading figures in French Academic painting. His careful rejection of the avant-garde trends set him apart as a guardian of tradition.

The Rise of Gérôme: Historical and Orientalist Works

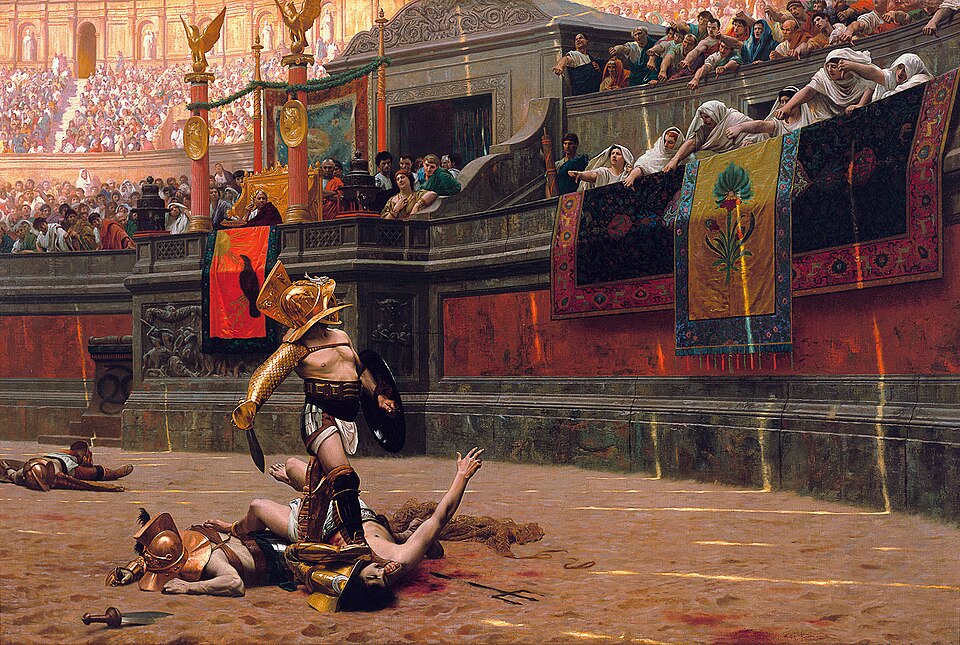

By the 1860s and 1870s, Gérôme had firmly cemented his status as a master of Academic art. His painting “The Death of Caesar” (1867) captured the aftermath of a pivotal historical moment with chilling realism and theatrical silence. In “Pollice verso” (1872), Gérôme presented the Roman gladiator arena in stunning detail, complete with bloodied sand, spectators, and imperial cruelty. These works combined archaeological precision with cinematic storytelling—hallmarks of his mature style.

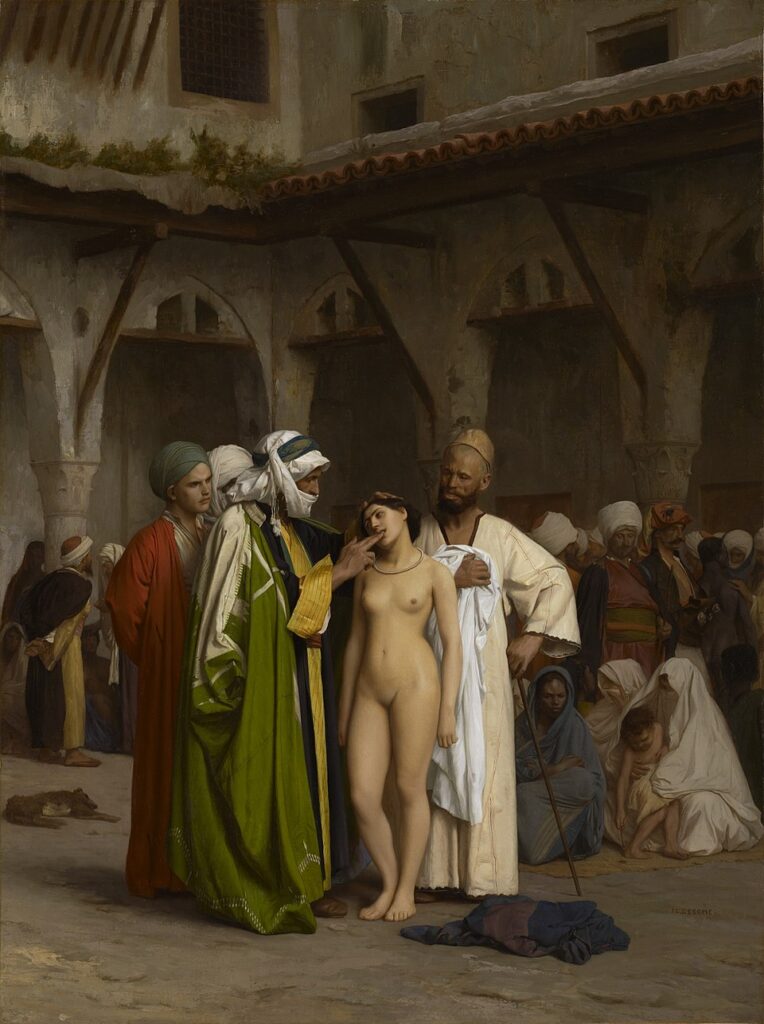

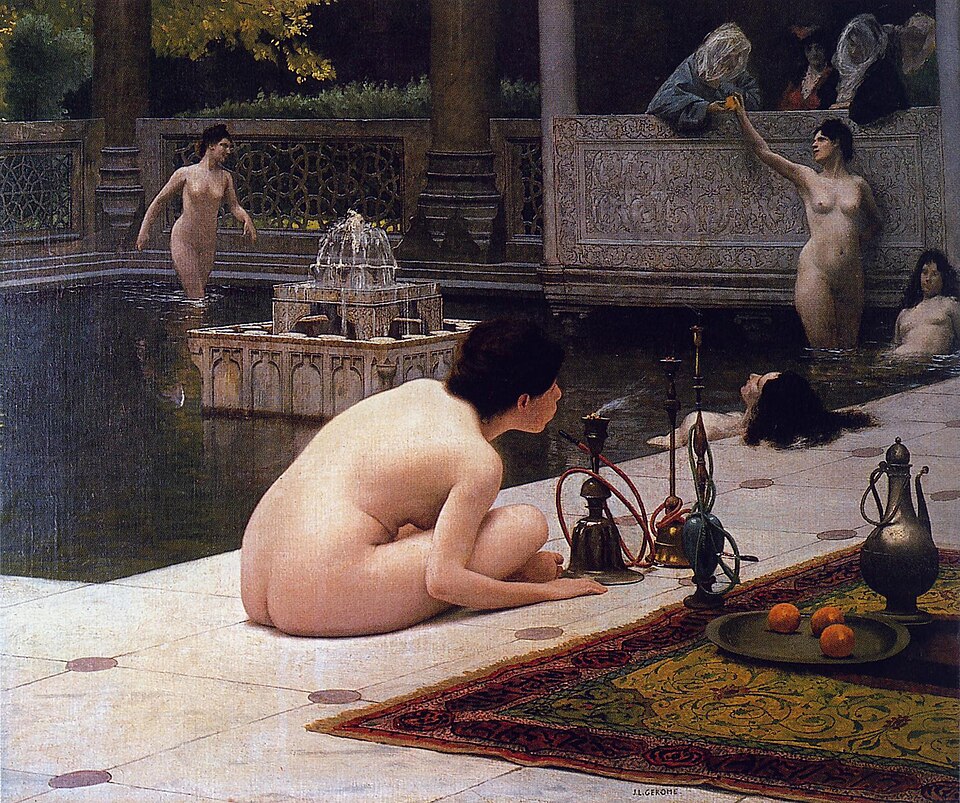

Gérôme’s growing interest in the Middle East began to define another major branch of his work. Starting in the 1850s, he traveled to Egypt, Turkey, Syria, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. These journeys inspired a flood of Orientalist paintings that depicted mosques, markets, harem scenes, and desert landscapes. Unlike mere fantasy, Gérôme took pride in rendering architectural and cultural details with a degree of accuracy rare in his time.

Defining an Era of Painting

His most iconic Orientalist works include “The Snake Charmer” (c. 1879), “Prayer in the Mosque” (1871), and “The Carpet Merchant” (1887). These pieces, often tinged with mystery and exoticism, captivated European audiences eager for visions of faraway lands. Gérôme’s command of texture, color, and architecture made these scenes as technically impressive as they were evocative. However, modern scholars debate whether these images romanticized foreign cultures through a Western lens.

Still, Gérôme saw himself as a documentarian of his time, capturing people and places before they were transformed by modernization. His Orientalist paintings remain among the most reproduced of his works and continue to appear in museums around the world. Despite the criticisms, the craft behind each canvas remains undeniable. Gérôme’s influence even extended into early Hollywood depictions of ancient and Eastern settings.

Gérôme the Sculptor and Educator

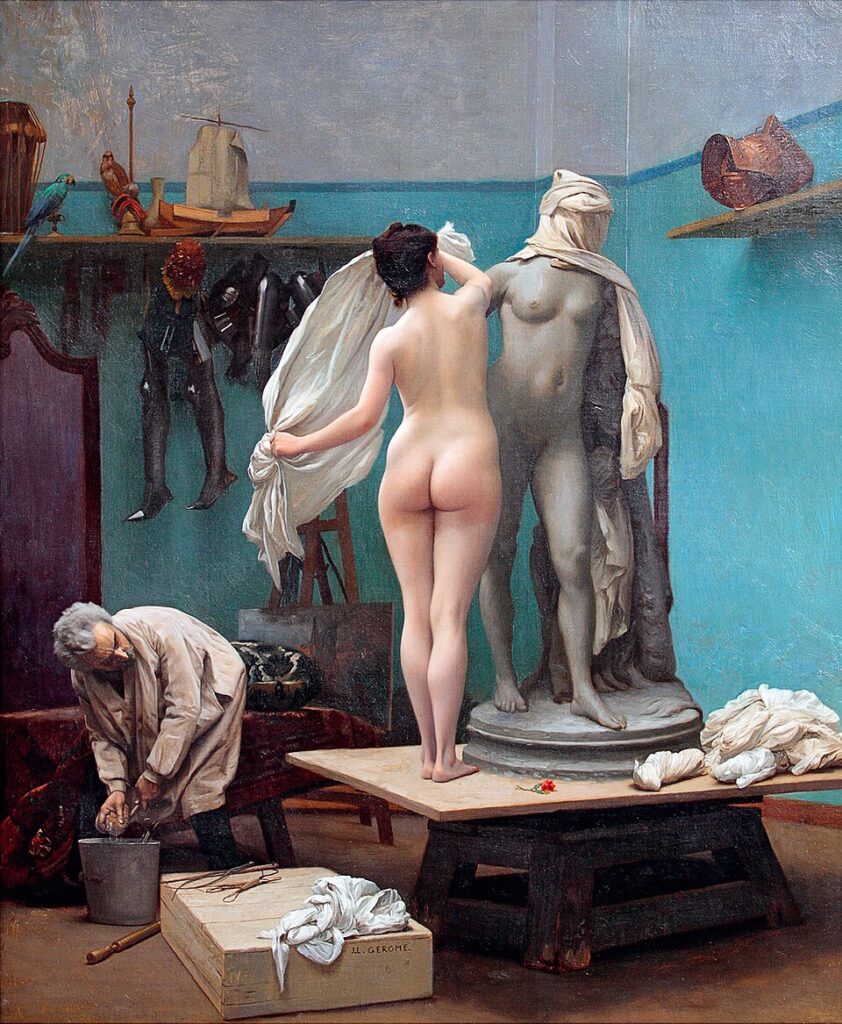

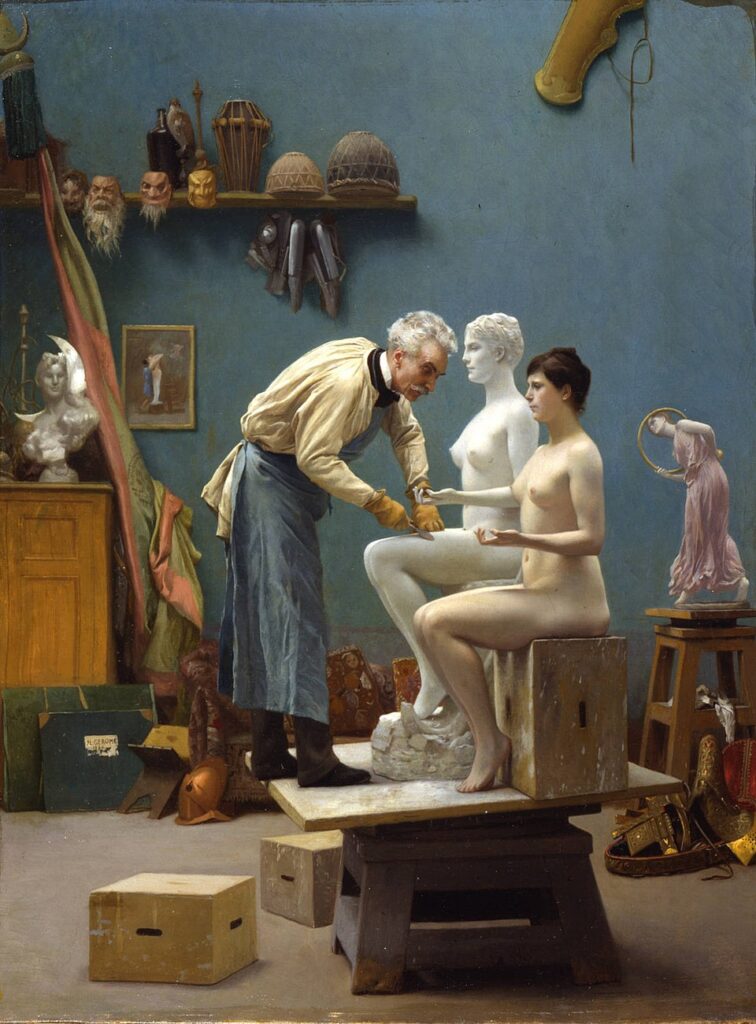

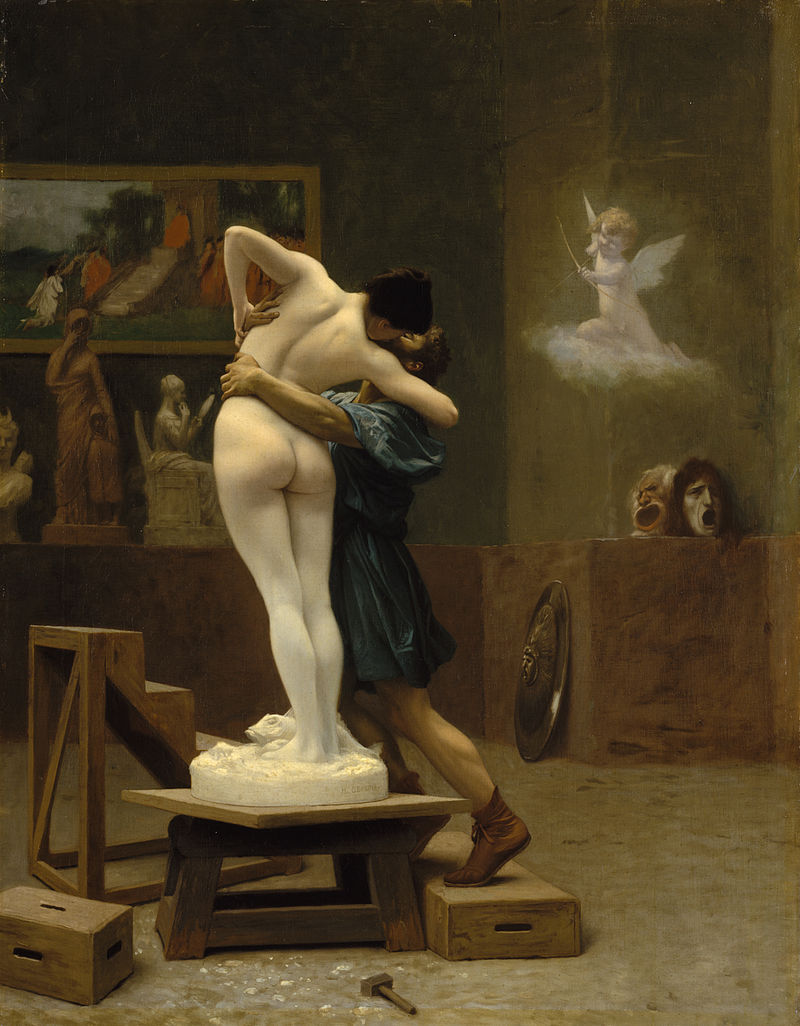

In addition to painting, Gérôme began producing sculpture in the late 1870s, proving that his artistic talents extended beyond the canvas. His three-dimensional works often revisited themes from his paintings, blurring the line between static pose and narrative drama. His most famous sculpture, “Tanagra” (1890), depicts a graceful young dancer and reflects his continued fascination with the ancient world. Through sculpture, he demonstrated the same precision and attention to detail that characterized his paintings.

Beyond his studio work, Gérôme also played a significant role as a teacher and mentor. In 1864, he was appointed professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he trained a generation of artists. His teaching emphasized drawing from life, mastery of anatomy, and adherence to classical values. Though his style fell out of favor during the rise of Impressionism, many of his students became accomplished painters in their own right.

Professor at the École des Beaux-Arts

Among his notable pupils were Odilon Redon, Aimé Morot, and Jules Bastien-Lepage, each of whom developed distinct voices despite their shared academic foundation. Gérôme’s influence was not only technical but also philosophical; he viewed art as a serious, intellectual pursuit rather than a vehicle for personal emotion or experimentation. His strict approach set him apart from the emerging modernists but earned him deep respect among traditionalists.

In the face of growing avant-garde movements, Gérôme defended Academic art passionately. He publicly criticized the Impressionists and rejected their loose brushwork and subjective vision. While this made him controversial in progressive circles, it also affirmed his status as a defender of artistic order and discipline. Gérôme’s dual legacy as a sculptor and educator showcases the depth of his commitment to the ideals of classical beauty and form.

Personal Life, Partnerships, and Public Standing

Gérôme married Marie Goupil in 1863, linking him to one of the most powerful art market networks of the 19th century. Marie’s father, Adolphe Goupil, was a leading art dealer whose firm, Goupil & Cie, handled Gérôme’s sales and reproductions. This partnership allowed Gérôme’s works to circulate internationally, reaching audiences in Britain, America, and across Europe. The Goupil connection ensured Gérôme’s financial security and market dominance for decades.

Though a man of discipline in his studio, Gérôme led a socially active life and remained deeply connected to the elite circles of French art and politics. He became a member of the Institut de France and held numerous honors, including the Legion of Honor, which he was awarded in several grades throughout his career. He cultivated friendships with other artists, but also maintained firm ideological lines, especially when it came to style and technique.

Marriage, Relationships, and Reputation

His vocal opposition to modern movements earned him both respect and criticism. While the official art establishment championed him, younger artists viewed him as an obstacle to innovation. This tension mirrored the broader artistic shifts in France during the late 19th century. As Monet and Degas gained prominence, Gérôme remained resolutely academic, standing firm against trends he saw as disorderly or indulgent.

Despite these debates, Gérôme’s status never truly diminished during his lifetime. He remained a popular figure in public exhibitions and maintained a strong collector base. His ability to navigate both the art world and the business of art set him apart. By the turn of the century, Gérôme was not only a senior figure of French art but also a symbol of the tradition he so faithfully served.

Death, Legacy, and Artistic Impact

Jean-Léon Gérôme died on January 10, 1904, in Paris, at the age of 79. He was buried with honors at the Montmartre Cemetery, a resting place for many of France’s artistic giants. At the time of his death, he was celebrated as one of the last great Academic painters of the 19th century. His passing marked the end of an era, as newer styles like Fauvism and Cubism were poised to dominate the early 20th century.

In the years following his death, Gérôme’s reputation declined sharply. The dominance of modernist art pushed academic painting out of critical favor, and Gérôme was dismissed by some as old-fashioned. Yet, beginning in the late 20th century, art historians began to reassess his work, recognizing the technical brilliance and cultural value of his paintings. Scholars like Linda Nochlin brought renewed attention to Gérôme’s role in Orientalism, prompting a fresh wave of analysis.

From Fame to Reappraisal

Today, Gérôme’s works are housed in major institutions around the world, including the Musée d’Orsay, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Getty Museum. His paintings are often featured in exhibitions examining realism, Orientalism, and 19th-century Academic art. In addition to their visual appeal, his works are now studied for what they reveal about 19th-century views on history, race, and empire. This dual legacy—both artistic and cultural—makes Gérôme a figure of enduring interest.

While his ideals of strict academic order may seem distant from today’s fluid styles, his craftsmanship continues to impress. The intricate details, polished surfaces, and grand narratives of Gérôme’s paintings still command admiration. In the ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation, Jean-Léon Gérôme remains a powerful voice from the classical side of the spectrum.

Key Takeaways

- Jean-Léon Gérôme was born in 1824 in Vesoul and died in 1904 in Paris.

- He studied under Delaroche and became a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts.

- His historical and Orientalist works made him a leading Academic painter.

- Gérôme also became a sculptor and influenced many future artists.

- Though once dismissed, his reputation has been revived in modern scholarship.

FAQs

- What style is Gérôme known for?

French Academic painting with historical and Orientalist themes. - Did Gérôme oppose modern art?

Yes, he strongly criticized Impressionism and other avant-garde movements. - What are Gérôme’s most famous works?

The Cock Fight, Pollice verso, and The Snake Charmer. - Was Gérôme also a sculptor?

Yes, he created notable sculptures like Tanagra in the 1890s. - Where are Gérôme’s paintings displayed?

Major museums like the Musée d’Orsay, the Met, and the Getty.