Natural disasters often bring chaos and devastation, but sometimes, they play an unexpected role as accidental protectors of art. From volcanic eruptions to floods and earthquakes, these catastrophic events have preserved paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, and artifacts that would otherwise have faded away with time. Sealed under ash, buried in mud, or submerged in water, these works of art were shielded from decay, creating time capsules of cultural heritage. Here are 20 remarkable stories of how nature’s fury unexpectedly safeguarded some of the world’s most precious artistic treasures.

1. Mount Vesuvius Eruption (79 AD) – Pompeii and Herculaneum Frescoes

The catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD unleashed fiery ash and pumice over Pompeii and Herculaneum, abruptly burying both cities. While devastating, this rapid burial preserved vivid frescoes in homes, temples, and public spaces. The thick layers of volcanic ash created an airtight, low-oxygen environment that halted the decomposition of these intricate artworks. As a result, vibrant wall paintings depicting mythological figures, daily activities, and elaborate decorative patterns remained largely intact.

These frescoes reveal much about Roman life and artistic preferences, showcasing themes of mythology, nature, and domestic leisure. Notable works include the “Villa of the Mysteries” in Pompeii, with its enigmatic Dionysian scenes, and Herculaneum’s depictions of marine life and daily commerce. The preservation of fine details, colors, and perspective provides an unparalleled view into Roman painting techniques and cultural aesthetics.

Today, Pompeii and Herculaneum offer some of the best-preserved examples of Roman wall art. The vivid reds, yellows, and blues seen in these frescoes help historians reconstruct the artistic and social life of ancient Rome, making them an invaluable resource for understanding ancient art. Ironically, the very disaster that obliterated these cities ensured the survival of these iconic artworks.

2. Shaanxi Earthquake (1556) – Cave Temples of China

The Shaanxi Earthquake of 1556 remains the deadliest in recorded history, with an estimated 830,000 casualties. This massive seismic event not only reshaped the landscape but also inadvertently preserved numerous Buddhist murals and sculptures in cave temples across the region. The quake caused significant rockfalls and landslides, which sealed off entire sections of caves, shielding them from human interference and natural weathering.

The preserved murals date back to the Tang dynasty and earlier, depicting colorful scenes of Buddhist iconography, from intricate bodhisattvas to mandalas. The pigments, applied using advanced techniques, retained their vibrancy thanks to the lack of air and moisture. Some of the caves also housed sculptures, which remained intact beneath the fallen rock, offering rare glimpses into Tang-era religious and artistic expression.

These cave paintings and sculptures are now critical to understanding the development of Buddhist art in China. Their preservation has provided insights into Tang artistic styles, religious symbolism, and even socio-political influences of the time. The earthquake, while a tragedy, acted as a strange guardian, keeping these sacred artworks safe for future generations.

3. Thonis-Heracleion’s Submersion (6th Century AD) – Egyptian Artifacts

Once a bustling port city, Thonis-Heracleion served as a major hub for trade and culture in ancient Egypt. However, a series of earthquakes and floods in the 6th century AD submerged the city, where it remained lost beneath the Mediterranean for over a millennium. This submersion preserved statues, pottery, inscriptions, and other ceremonial objects in an oxygen-poor environment, effectively halting decay.

Archaeologists have uncovered colossal statues of gods and pharaohs, intricately carved stelae, and Greek-Egyptian sculptures that reflect the Hellenistic influence of the period. These discoveries offer insights into the fusion of Egyptian and Greek artistic traditions, visible in the statuary’s mix of Egyptian symbolism and Greek naturalism. The silt covering these artifacts acted as a natural sealant, keeping their surfaces and details remarkably intact.

The underwater find of Thonis-Heracleion has been a game-changer for understanding late-period Egyptian art and religion. The preserved objects reveal a wealth of information about ancient rituals, trade practices, and artistic innovations. The city’s submersion, once a disaster, has become one of archaeology’s most significant underwater discoveries.

4. Santorini Eruption (circa 1600 BC) – Akrotiri Frescoes

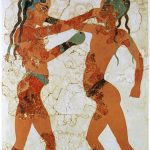

The eruption of Santorini (ancient Thera) around 1600 BC buried the Minoan city of Akrotiri under several meters of volcanic ash. This catastrophic event sealed off the entire settlement, preserving frescoes, pottery, and architecture. The ash formed an airtight cocoon, stopping the usual deterioration caused by air and moisture, allowing the frescoes to retain their bright colors and fine details.

The frescoes of Akrotiri depict scenes of everyday Minoan life, marine imagery, and mythological themes. Notable works include the “Spring Fresco,” with its vibrant floral motifs, and the “Boxing Boys,” showcasing athletic competitions. The preserved wall paintings provide a window into Minoan aesthetics, characterized by naturalistic styles, dynamic compositions, and an emphasis on color.

These frescoes are among the best-preserved examples of Bronze Age art, offering crucial insights into Minoan culture, religious practices, and artistic techniques. The Santorini eruption, while devastating, allowed these artworks to survive for thousands of years, revealing the sophistication of Minoan civilization to modern archaeologists.

5. Petra Landslides (4th Century) – Nabatean Rock Art

In the 4th century, a series of earthquakes and landslides struck Petra, the rose-red city carved into the cliffs of present-day Jordan. While these landslides caused significant damage to Petra’s infrastructure, they also buried many of its intricate rock carvings, bas-reliefs, and sculptures. The fallen rock acted as a protective barrier, keeping the artworks safe from wind erosion and human interference.

The buried carvings depict Nabatean gods, mythological scenes, and ornamental designs that highlight the Nabateans’ skill in stone carving. Some of the best-preserved bas-reliefs include images of deities like Dushara and Al-Uzza, as well as detailed decorative friezes that adorned temple facades and tombs. The landslides essentially “froze” these artworks in time, preventing centuries of exposure to harsh desert conditions.

Today, Petra’s rock art serves as a testament to Nabatean religious and artistic traditions. The preserved carvings provide vital insights into the syncretic culture of the Nabateans, who blended Arabian, Hellenistic, and Roman influences in their art. The landslides, though catastrophic, have allowed modern archaeologists to study this ancient civilization’s art in remarkable detail.

6. Tenochtitlan Flooding (1521) – Aztec Codices

During the siege of Tenochtitlan in 1521, the Spanish forces’ efforts to breach the city led to extensive flooding, exacerbated by heavy rainfall. While the flooding caused significant devastation to the Aztec capital, it also inadvertently submerged some of the city’s codices in waterlogged conditions. These codices, created with pictographic art and detailed iconography, were preserved in thick mud that restricted oxygen exposure.

The surviving codices feature a mix of religious, astronomical, and historical themes, often presented in colorful illustrations on amate paper. The mud acted like a sealant, keeping the pigments and fibers largely intact. Some of these codices were later recovered, offering rare insights into Aztec mythology, political structures, and daily life.

These codices are among the few surviving primary sources of Aztec culture, as most were destroyed during the conquest. The floodwaters, ironically, saved them from complete destruction, preserving a critical part of Mesoamerican art and history that continues to inform scholars today.

7. Lake Titicaca Submersion (Pre-Columbian Era) – Incan Offerings

Lake Titicaca, located at high altitude in the Andes, was a sacred site for the Incas. Ritual offerings were often made by submerging objects like gold figurines, ceramics, and textiles into the lake’s waters. The cold, low-oxygen conditions at the lakebed preserved these items in remarkable condition, halting the usual processes of organic decay.

Many of these preserved offerings display fine craftsmanship, including gold figurines depicting deities, ornately painted ceramics, and intricately woven textiles. The artistic objects reflect the Incas’ religious beliefs, as well as their mastery in metalwork, pottery, and weaving. The lake’s conditions acted as a natural protector, allowing many of these items to retain their original detail and color.

The discoveries from Lake Titicaca have provided crucial insights into Incan religious rituals and artistic traditions. The preservation by submersion has offered an exceptional window into pre-Columbian art, revealing a culture deeply connected to the spiritual symbolism of water.

8. Mont Blanc Avalanche (1820) – Renaissance Church Artifacts

An avalanche near Mont Blanc in 1820 buried parts of a monastery, along with Renaissance-era church artifacts stored in an annex. The heavy snow and ice acted as an insulator, preserving wooden altarpieces, manuscripts, and sculptures that would have otherwise decayed over time. The avalanche’s cold, stable environment prevented rot and deterioration, much like a natural deep-freeze.

The preserved items include intricately carved wooden altarpieces, illuminated religious texts, and delicate sculptures, all of which remained intact beneath the snow. The manuscripts retain their detailed calligraphy and decorative flourishes, providing rare examples of Renaissance religious art and literature from the Alpine region.

Rediscovered decades later, these artworks offered a glimpse into the religious and artistic practices of Renaissance Europe. The avalanche’s unintended preservation highlighted the resilience of art when nature itself becomes a protective force.

9. Novgorod Floods (12th Century) – Medieval Birch Bark Manuscripts

The medieval city of Novgorod, located in present-day Russia, experienced frequent flooding throughout its history, particularly in the 12th century. These floods caused birch bark manuscripts, often discarded or lost, to become buried in waterlogged soils. The anaerobic conditions preserved not only the bark but also the ink and calligraphy, which often included ornate medieval illustrations.

The manuscripts offer unique insights into medieval Slavic culture, language, and art, with some featuring detailed drawings and symbolic motifs alongside written texts. The birch bark’s natural durability, combined with the preserving power of the waterlogged conditions, maintained the legibility and artistry of these documents over centuries.

Today, the Novgorod manuscripts are celebrated as some of the earliest examples of medieval Slavic art and writing. The floods that initially threatened the city ironically became the reason why these artifacts survived in such good condition, providing a wealth of information about medieval Russia.

10. Helike Submersion (373 BC) – Greek Artifacts

The city of Helike, located in ancient Greece, was swallowed by an earthquake-induced tsunami in 373 BC. The rapid submersion in seawater buried statues, pottery, and decorative objects under layers of silt, creating a low-oxygen environment that preserved them for millennia. The silt’s protective qualities helped maintain the fine details of the artworks, which might have eroded on land.

The artifacts recovered from Helike include bronze statues, ornate pottery, and architectural elements decorated with Greek motifs. The city’s sudden disappearance beneath the waves kept these objects away from the elements and human activity, allowing them to remain largely intact until modern excavations uncovered them.

Helike’s rediscovery has shed light on Classical Greek art and urban life. The natural disaster that obliterated the city paradoxically ensured the survival of many artworks that reflect Greek artistic traditions, religious beliefs, and social structures.

11. Antikythera Storm Shipwreck (1st Century BC) – Submerged Greek Artifacts

The Antikythera shipwreck, which sank in the 1st century BC due to a severe storm off the coast of Greece, preserved a treasure trove of Greek artifacts. Among the finds are bronze and marble statues, intricately decorated pottery, and the famed Antikythera Mechanism, often regarded as the world’s first analog computer. The storm-driven submersion created a low-oxygen, sediment-rich environment that preserved the artifacts for over two millennia.

The statues, many of which depict gods, athletes, and mythological creatures, display the Hellenistic mastery of realism and detail. The bronze sculptures, in particular, retained their form and intricate features, protected by the silt and sea floor sediment that surrounded them.

The discovery of the Antikythera shipwreck has been pivotal in understanding ancient Greek art and technology. The preservation by submersion, although caused by a catastrophic storm, kept the artifacts intact, offering unparalleled insights into Hellenistic art, trade, and craftsmanship.

12. Japanese Typhoon of 1281 – Kamakura Artifacts

The “Divine Wind” (Kamikaze) typhoon of 1281 famously protected Japan from Mongol invasion, but it also had an unexpected impact on preserving Kamakura-era religious sculptures and artifacts. The typhoon altered coastal landscapes, creating natural barriers around remote temples that housed Buddhist sculptures and religious icons. As these sites became more isolated, they were shielded from the usual risks of looting, fire, and other natural elements.

The preserved artifacts include wooden sculptures of Buddhist deities and ritual objects crafted with intricate carvings and lacquer. These pieces are representative of Kamakura art, known for its realism and martial themes, often depicting samurai alongside Buddhist icons. The isolation caused by the typhoon kept these items away from conflict zones and helped maintain their original condition for centuries.

Rediscovered during later periods, these artworks provide critical insights into Kamakura religious practices and artistic styles. The typhoon’s role in preserving the artifacts underscores how natural disasters can protect cultural heritage in surprising ways, enabling historians to study a relatively intact segment of medieval Japanese art.

13. Solovetsky Monastery Flood (17th Century) – Preserved Religious Icons

In the 17th century, severe flooding struck the Solovetsky Monastery on the Solovetsky Islands in Russia’s White Sea. The rising waters inundated the lower storage areas of the monastery, submerging religious icons and manuscripts. The cold, waterlogged conditions created an anaerobic environment, which prevented the usual decay of wooden icons and painted surfaces.

The icons, intricately painted with religious scenes and saints, featured traditional Russian iconographic styles. The thick, cold floodwaters sealed off the artifacts from oxygen and pests, keeping the pigments vibrant and the wood stable. Even the gold leaf and fine brushwork were preserved, providing a rare opportunity to study 17th-century Russian ecclesiastical art in its original form.

Today, these preserved icons are a testament to the craftsmanship of Russian Orthodox religious art. The unexpected preservation caused by flooding, despite its devastating effects on the monastery, paradoxically became a means of safeguarding this cultural heritage for centuries to come.

14. Herculaneum Mudflows (79 AD) – Roman Wooden Structures

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD did not just bury Pompeii—it also buried Herculaneum under pyroclastic mudflows. Unlike Pompeii, Herculaneum was engulfed by hot mud that carbonized and preserved wooden structures, furniture, and organic materials. The mud created an anaerobic environment, which protected wood and papyri from complete decomposition over nearly 2,000 years.

Among the preserved items are wooden beds, shelving units, and intricate doors, offering a glimpse into Roman domestic life and carpentry techniques. The Villa of the Papyri, a grand estate in Herculaneum, also preserved its collection of scrolls through a similar carbonization process, though these fall more into the realm of literature than art.

The mudflows’ preservation of wooden artifacts is a rare feat in Roman archaeology, as wood typically decomposes rapidly. The eruption, while catastrophic, thus acted as an unintentional preserver of artistic woodwork and domestic design, showcasing Roman craftsmanship in an unparalleled way.

15. Avalanche at Mont Blanc (1820) – Renaissance Artifacts

An avalanche near Mont Blanc in 1820 buried parts of a monastery and its annex, which stored Renaissance-era church artifacts. The sudden deposit of heavy snow and ice created a natural deep-freeze that preserved wooden altarpieces, religious sculptures, and manuscripts. The cold, stable conditions prevented the organic materials from decaying over time.

These artifacts include carved wooden altarpieces featuring detailed religious scenes, alongside illuminated manuscripts with vibrant illustrations and calligraphy. The avalanche acted like a protective shield, maintaining both the structure and artistic details of these works, which otherwise would have faced decay in fluctuating temperatures.

Rediscovered decades later, the artifacts provide a valuable glimpse into Renaissance religious art in the Alpine region. The avalanche’s preservation serves as an example of how even the most destructive natural events can become unintentional conservators of cultural heritage.

16. Krakatoa Eruption (1883) – Preserved Indonesian Carvings

The catastrophic eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 sent massive waves and volcanic ash across the Sunda Strait, devastating surrounding areas. The ashfall buried villages and coastal structures, including traditional Javanese and Sumatran buildings adorned with intricate wood carvings. The volcanic ash created a seal that protected these artworks from weathering and other natural decay.

The preserved carvings include traditional Indonesian motifs depicting nature, mythological creatures, and religious symbolism, all typical of local woodcraft. The rapid burial by ash and pumice, combined with a lack of oxygen, kept the delicate carvings intact, halting the normal decay that tropical climates typically cause to organic materials like wood.

This unexpected preservation provides insights into late 19th-century Indonesian art and craftsmanship, particularly in the areas affected by the eruption. The Krakatoa disaster, while one of the most violent eruptions in recorded history, ironically preserved a slice of cultural heritage that would otherwise have been lost to time and the elements.

17. Burg Eltz Flooding (1331) – Medieval Manuscripts

Flooding of the Moselle River in 1331 inundated parts of Burg Eltz, a medieval castle in Germany, submerging vaults that contained illuminated manuscripts. The floodwaters created anaerobic, waterlogged conditions that preserved the manuscripts’ parchment and ink, which would have otherwise decomposed over time.

The illuminated manuscripts include religious texts with elaborate decorative borders, gold leaf accents, and hand-painted miniatures, typical of medieval artistry. The waterlogged state preserved the vibrancy of the colors and the integrity of the parchment, keeping the artistry intact for centuries.

The survival of these manuscripts offers insights into medieval Germanic religious practices and manuscript art. The flooding, while destructive, unintentionally became a preserver of delicate art, making Burg Eltz a rare case of disaster-driven conservation of medieval manuscripts.

18. Temple of Apollo at Didyma (1493 Earthquake) – Preserved Sculptures

The Temple of Apollo at Didyma, located in modern-day Turkey, was struck by a major earthquake in 1493 that caused parts of the temple to collapse. This disaster, while devastating to the temple’s structure, buried many of its statues and reliefs under heavy stone debris. The fallen debris acted as a protective layer, shielding the sculptures from subsequent looting and weathering.

The preserved sculptures include depictions of Apollo, mythological creatures, and ornamental friezes that adorned the temple walls. The earthquake’s impact kept the sculptures in relatively good condition, with detailed carvings and fine artistic touches maintained over centuries.

The rediscovery of these sculptures has provided insights into Hellenistic artistic styles, especially in religious contexts. The earthquake’s protective effect illustrates how sudden natural events can sometimes act as unintentional guardians of cultural treasures.

19. Mount Mazama Eruption (circa 7,700 years ago) – Native American Artifacts at Crater Lake

The eruption of Mount Mazama in present-day Oregon created Crater Lake, burying nearby settlements and artifacts under volcanic ash. The rapid deposition of ash preserved a variety of Native American artifacts, including tools, ceremonial objects, and artistic carvings, all of which were sealed in a low-oxygen environment.

The preserved objects reveal intricate designs and motifs, such as carvings on stone tools and ceremonial items decorated with animal symbolism. The ash’s insulating properties helped maintain the artifacts’ integrity, keeping the fine details of the carvings intact for millennia.

These discoveries provide valuable insights into the culture and art of early Native American societies in the Pacific Northwest. The catastrophic eruption that destroyed settlements ironically ensured the survival of significant artistic heritage, making Crater Lake a vital archaeological site.

20. Mount Pelée Eruption (1902) – St. Pierre Artifacts

The eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902 devastated the town of St. Pierre on the island of Martinique, killing nearly all of its 30,000 residents. Pyroclastic flows and ash buried the town’s buildings, sealing household items, ceramics, and decorative objects under layers of volcanic debris. The rapid burial created a low-oxygen environment that preserved many artifacts in their original state.

Recovered artifacts include intricately designed ceramics, ornate glassware, and household decorations that provide a glimpse into the colonial lifestyle of St. Pierre before the eruption. The intense heat also carbonized some wooden structures, preventing them from complete decomposition.

The disaster’s impact, while tragic, has allowed for an unusually well-preserved record of turn-of-the-century Caribbean culture. The buried objects offer insights into colonial art, daily life, and decorative tastes, making Mount Pelée’s eruption a pivotal event in the preservation of historical artifacts.