When settlers first moved into the valleys and ridgelines of what would later become West Virginia, they carried very little with them but their tools, their faith, and their memory of the old world. What they created in this new environment was not art in the conventional sense, but it was unmistakably artistic: functional objects shaped with care, ornamented with pride, and passed down with reverence. The mountainous isolation of the region incubated a visual culture based not on formal education or market trends, but on inherited craft traditions and immediate necessity. The result was a body of material culture where utility and aesthetic instinct became indistinguishable.

Whittled, Woven, and Wrought: Settler Crafts as Early Expression

The earliest decorative arts in the region emerged from a context of survival. German and Scots-Irish immigrants—two of the dominant cultural groups populating western Virginia in the 18th century—brought with them established craft vocabularies that adapted to Appalachian materials. These influences could be seen in hand-carved chests, dyed wool coverlets, and the distinctive hex signs painted on barns, often meant to ward off misfortune as much as to beautify.

Among the most vivid surviving expressions of this period are quilts made by frontier women. These quilts, far from being mere blankets, often displayed geometric complexity and symbolic motifs. The “Log Cabin” pattern, with its concentric arrangement of fabric strips around a central square, reflected both the architecture of Appalachian life and the structured repetition familiar from European folk traditions. Unlike the quilts of more urbanized or genteel communities, these works were often made from salvaged scraps—shirt cotton, flour sacks, and worn-out dresses—stitched together in ways that carried memory and message as well as warmth.

Three common domestic objects from the era—each rich in implicit artistry—included:

- Carved powder horns etched with names, dates, or animals

- Painted dower chests for storing linens and heirlooms

- Ladder-back chairs with hand-woven hickory bark seats

The cumulative effect of these small works was a household environment that, while rustic, bore the unmistakable marks of human design and symbolic intent. These were not amateurish gestures toward “high art,” but deliberate articulations of taste and belief within the strict limits of labor, time, and isolation.

Churches and Signs: Early Religious and Communal Visuals

Religious life was central to most Appalachian settlements, and while permanent church buildings were slow to appear, many early log meetinghouses included painted decorations or symbolic carvings. These were not cathedral murals or stained-glass extravagances but spare, often haunting images: cruciform motifs scratched into doors, scripture verses painted along beams, and simple panel paintings brought over from older congregations in Pennsylvania or Maryland.

Perhaps more widespread, and more visually assertive, were the hand-painted signs and placards used for wayfinding, trade, and preaching. Itinerant ministers and peddlers often carried boards or banners painted with biblical passages, local advertisements, or even hand-drawn maps. These hybrid objects—somewhere between folk art, signage, and proselytizing media—offer a glimpse into the visual literacy of early mountain communities. Decoration served not just as beauty but as broadcast.

Unexpected Ornament: The Rifle as Canvas

The long rifle, often called the “Kentucky rifle” but manufactured and used just as often in western Virginia, was another object where function and form became inseparable. Known for their slender barrels and accuracy, these rifles were also embellished with elaborate inlays—silver, brass, bone—forming scrollwork, stars, and initials. The rifles served as a frontier man’s most valued possession, and the decoration reflected that status. While these embellishments were rarely signed, the work of regional gunsmiths can sometimes be traced through distinctive flourishes: a signature leaf motif here, a compass star there.

These rifles stand as an early example of frontier object-making that transcended mere utility. They were deadly instruments, yes—but also talismans, heirlooms, and artworks. The same could be said of the powder horns that accompanied them, often carved with names, battle dates, or hunting scenes in a folk-engraving style that now appears strangely elegant in its roughness.

Micro-Narrative: A Chest in the Wilderness

In 1798, near what is now Elkins, a settler named Johann Voss built a log cabin and brought with him a painted chest inherited from his father in Bavaria. The chest, decorated with naïve floral patterns in red, green, and yellow, was one of the few pieces of furniture he did not craft himself. It became a point of fascination in the valley, something almost mythic in its visual contrast to the unpainted, self-built world around it. Local children believed it was a kind of shrine; his neighbors asked to borrow it to trace the designs onto their own furniture. Voss died in 1811, and the chest disappeared sometime in the following decades—but the memory of it persisted, mentioned in letters and oral histories. It is one of many such stories where a single imported or decorated object helped ignite the idea of visual richness amid harsh surroundings.

Isolated Brilliance and the Lack of “Art” Markets

The region’s remoteness from cities like Richmond or Philadelphia meant that very little fine art—portraits, oil paintings, or sculpture—circulated in early West Virginia. This absence created both a limitation and a freedom. On one hand, there was no infrastructure for training or exhibiting work; on the other, there was no pressure to conform to prevailing academic tastes. What emerged was a quietly insistent localism, expressed through materials at hand: cherry wood, clay, walnut, beeswax, and homespun wool.

Because of this, very little from the pre-1850 era survives in museum collections under the label of “art.” Instead, the record is maintained through historical societies, church archives, and private collections where labeled boxes of “tools,” “textiles,” or “oddities” contain the aesthetic DNA of early West Virginia. In recent decades, some of these objects have begun to be reclassified—not just as folk art, but as early American art in their own right.

The Aesthetic Legacy of Early Settlement

By the time West Virginia separated from Virginia in 1863, the region had already developed a distinct visual identity rooted in physical labor, European craft memory, and Appalachian resourcefulness. While painters and sculptors were still rare, the foundation had been laid—not in the studios of patrons or academies, but in the hands of weavers, carvers, and builders whose creations were not named as art, but seen and remembered all the same.

These traditions would not vanish as industry and modernity approached. They would mutate, resurface, and assert themselves in surprising ways in the decades to come—sometimes literally, as old quilts and tools reappeared in museums, and sometimes spiritually, as later artists looked back to the untrained clarity of their great-grandparents’ hands.

Chapter 2: Painted Landscapes and the Ideal of Wilderness

Long before industrial smoke rose over canyons or glassworks chimneys pierced the skyline, many of the earliest—and most compelling—visual evocations of what would become West Virginia came not from local studios or galleries, but from traveling artists, mapmakers, and settlers who tried to capture the grandeur of the land itself. The mountains and rivers, the folds of ridges and valleys, became subject matter for an emerging visual vocabulary that would come to define how people imagined the region—both for those who lived there and those who looked on from afar.

The Alleghenies Imagined: First Visual Impressions

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as settlers—often of German, Scots‑Irish, and other European descent—pressed deeper into what was then the western frontier of Virginia, the landscapes they traversed left a powerful imprint. For many, these scenes called for more than pragmatic rendering; they invited wonder, longing, even a kind of spiritual reverence. Out of necessity or curiosity, itinerant painters and sketch‑makers began to record topography, settlements, and natural features—rudimentary maps, sketches, and watercolor washes that stored visual memories of rugged terrain, rivers, forested hollows.

These early images rarely survive today in large numbers. Their creators were seldom trained artists. Their works were not destined for salons. Instead, sketches served practical ends—surveying land, planning travel, or memorializing a home. But implicitly these renderings shaped a visual archive: of hidden hollows, misty ridges, winding rivers, and dense forest. Over time, this archive became part of the broader aesthetic by which outsiders—and eventually West Virginians themselves—understood the land.

Where settlers had once looked at raw wood and rock, they increasingly saw composition: foreground ridges, receding valleys, shifting light. And in that composition lay potential—not only for portraits of the terrain, but for symbolic meditations on solitude, perseverance, and home.

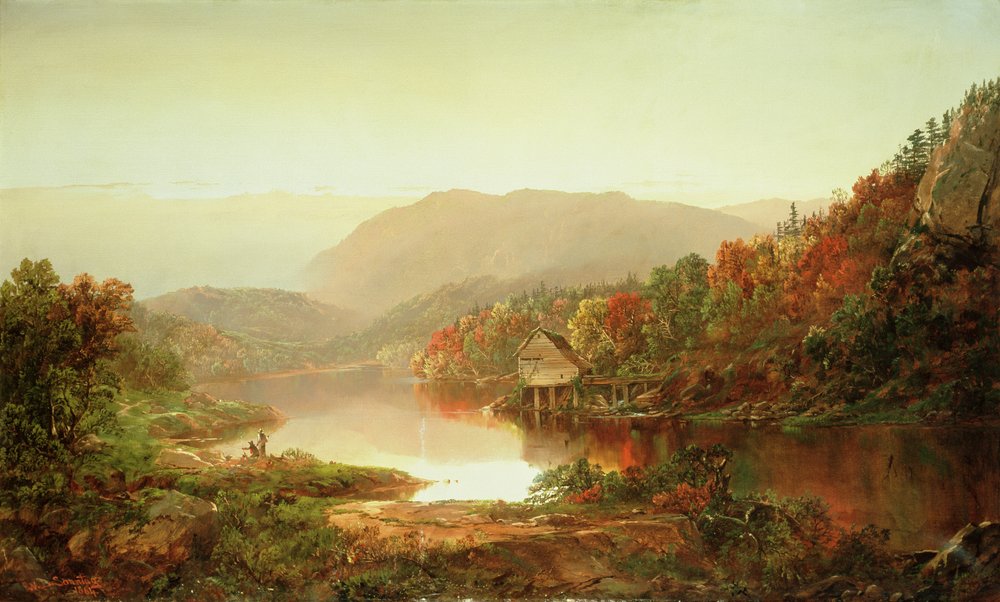

Echoes of the Hudson River School — A Mountain State’s Borrowed Palette

As the 19th century unfolded and American landscape painting matured, the taste for sublime, idealized nature spread. The Hudson River School, though rooted further north and east, left an unmistakable imprint on how Americans depicted wilderness. Its artists championed light, air, dramatic composition—and often framed natural scenes as moral or spiritual statements.

For West Virginia—land of mountains, waterfalls, deep hollows, and sweeping ridges—this influence proved potent. Even if the Hudson painters themselves rarely ventured deep into the rugged Alleghenies, their style offered aesthetic tools defenders of Appalachian scenery could borrow. Artists who painted local vistas borrowed not only technique but sensibility: atmospheric light filtering through pines, distant ridgelines fading into violet haze, rock cliffs rendered monumental.

Through such frames, the landscapes of West Virginia transformed from wilderness to something almost mythic: majestic, venerable, worthy of quiet admiration and contemplation. What may once have looked wild now became picturesque, domesticated into a visual language of beauty.

Journeys and Journals: Traveling Artists, Topographical Sketches, and Early Tourism

In the decades before railroads, before massive logging or mining reshaped valleys, naturalists, surveyors, and travelers passed through Appalachian terrain and sought to document their experiences. The river valleys—along the Kanawha, Shenandoah, New, and Green—became routes of exploration, commerce, and passage. With them came sketch‑books, journals, watercolors, and written descriptions.

These early “tour‑artists” sometimes worked independently, sometimes under commission. Their motivation ranged widely: surveying land, preparing maps for sale, providing illustrations for travel narratives, or simply preserving memories. Their works—topographical sketches of ridges, river crossings, settler cabins, waterfalls—constitute arguably the first cross‑section between documentary and aesthetic interest in West Virginia landscapes.

Although many such works remain unattributed or lost, the tradition seeded a visual appetite: for vistas, for scenic grandeur, for a sense of place rooted in nature. Over time, this appetite would morph beyond documentation, into appreciation—and even tourism. Later generations would revisit those same hillsides, seeking not only livelihood but beauty, solace, identity.

The Mountain State as Symbol — Wilderness as Identity

As artists internalized these natural forms, a symbolic identity began to emerge. The mountains, ridges, hollows, rivers—they became more than geography. They became emblems of endurance, quiet strength, and rootedness. In painted landscapes, the mountain ridgeline might loom large, the valley below mist‑shrouded; a solitary cabin might lie dwarfed against forested slopes. In these images, the human scale shrinks; nature seems to endure.

This portrayal resonated beyond the aesthetic. For residents and later generations, such images offered a mirror: rugged, serene, solitary, yet enduring. The land’s contours came to express resilience, stability, and a sense of home intertwined with place. From the early settlers’ utilitarian crafts (as examined in the previous chapter) to these painterly renderings, a continuum of attachment to place began to emerge—a deep, visual tying of identity to mountain and valley.

Seeds for Later Traditions

These early landscape sketches and painted vistas planted seeds. As centuries turned and West Virginia began to urbanize, industrialize, and modernize, the memory of its natural beauty and the visual vocabulary to express it would survive. Later generations—folk artisans, glassmakers, regional painters—would find in the mountain‑scapes a reference point. The shape of the land, the curve of a ridge at dusk, the glimmer of a stream in moonlight—these would reappear, reinterpreted in quilts, woodwork, glass, and canvas.

Even if first‑generation images were utilitarian or documentary, they carried within them the formative motifs: horizon lines broken by peaks, streams threading through hollows, light glancing off water or rock. These motifs would prove flexible, adaptable to other media, and enduring.

And though no formal “school” yet existed, the impulse to render environment, to commemorate place, to translate wild grandeur into human-readable images—this impulse itself had taken root. It would grow, mutate, return again, across generations.

Chapter 3: The Civil War and its Visual Legacy

A War That Drew Borders and Etched Memory into Stone

The American Civil War did more than divide a nation—it divided Virginia, permanently. From that rupture, West Virginia was born, carved in the midst of bloodshed and ideological conflict. But this foundational fracture was not merely legal or political. It left visual traces across the state: in the sketches made by amateur soldiers, the monuments erected by veterans’ groups, the forts dug into ridge lines, and the symbols chosen to define the fledgling state’s identity. Through these traces, the war remained visible long after the gunfire ceased.

A State Born in Conflict: The Visual Consequences of Secession

When West Virginia entered the Union on June 20, 1863, it became the only state to be formed by breaking away from a Confederate state. This fact alone lent its birth a unique symbolic intensity. The act of secession from Virginia—and simultaneous alignment with the Union—required not just legislative navigation but a redefinition of identity. Visual culture played a role in this redefinition from the beginning.

At Wheeling’s Independence Hall, which functioned as the de facto capital of Unionist Virginia during the war, federal flags were raised, portraits of Union leaders adorned the walls, and oratory echoed through ornate chambers. The building—built in 1860—became not only a political seat but a theatrical space in which a new statehood was imagined and staged. Today, preserved as a museum, it houses many of the era’s original banners, weapons, and period artifacts. These surviving objects, however modest, carry aesthetic weight: the hand-stitched regimental flags, painted signage, and early seals mark a moment when visual identity and state legitimacy were fused.

The state’s official motto, “Montani Semper Liberi” (“Mountaineers are always free”), was adopted shortly after formation. It appeared soon thereafter on carved plaques, government papers, and even militia standards. In a land of steep ridges and scattered loyalties, the phrase became more than Latin; it was a visual and verbal statement of self-possession.

Forts and Fieldworks: Where Art Meets Terrain

While grand battlefields like Gettysburg or Antietam captured national imagination, West Virginia’s wartime experience was largely defined by skirmishes, defensive positions, and irregular warfare—much of it inscribed directly into the land. Fort Scammon, located on a bluff overlooking Charleston, was one such site. Built in 1862–63, it consisted of earthen redoubts dug into the hillside, manned by Union forces to defend the Kanawha Valley.

Though hardly monumental in appearance, these works speak to a different kind of visual legacy: the war as landscape-alterer, carving lines into hills and leaving behind the geometry of violence. Fort Scammon survives as a physical document of war—a place where the viewer’s imagination is asked to supply the smoke, the uniforms, the crack of rifle and cannon. Like many such Civil War sites in West Virginia, its preservation is understated, local, and tactile. Earth, not marble, does the remembering.

Carnifex Ferry Battlefield State Park, farther south, tells a similar story. The battle fought there in September 1861 was small by national standards, but it marked a turning point in the Union’s early dominance of the region. Today, the battlefield remains open, with interpretive signs and walking trails tracing the ridges where troops once maneuvered. The aesthetics of such spaces are austere—grass, tree line, fence post—but the composition, the layout of action remembered, echoes the structure of a painting or diorama: an imagined clash, frozen by the viewer’s attention.

Soldier Art and Amateur Sketches: The War on Paper

West Virginia was not a hub of formal art production during the Civil War—there were no portrait studios or grand allegorical canvases painted in Wheeling or Charleston at the time. But soldiers from the region, like many others on both sides, often kept illustrated diaries or sent home decorated letters. These works, rarely preserved in major collections, were visual snippets: sketches of camp life, rough maps, caricatures of officers, and rudimentary depictions of battlefield scenes.

In the absence of academies or professional training, these soldier-artists embraced immediacy. A campfire sketch might show rows of tents against the mountains; a caricature might lampoon a particularly loathed sergeant. Their style was often crude, their materials poor—pencil stubs, cartridge paper—but their drawings served to humanize and interpret the war. In some families, such sketches were kept for generations. They became heirlooms more cherished than medals.

Some of these drawings eventually entered public archives, donated by descendants to libraries or historical societies. While rarely framed or publicly exhibited, they offer a firsthand visual account of the war’s texture: not the great battles, but the daily mud, the waiting, the strange mixture of boredom and terror. And in their unstudied lines, one sees a kind of truth that studio renderings sometimes lack.

The Rise of Commemoration: Monuments in Stone and Bronze

After the war, as veterans aged and memory hardened into history, a new phase of visual culture emerged: commemoration. Unlike the informal sketches or functional forts of wartime, postbellum monuments were public, permanent, and symbolic.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Wheeling, dedicated in 1883, stands among the earliest large-scale Civil War memorials in the state. Cast in bronze and mounted on a stone pedestal, it portrays a Union soldier standing at rest. The monument’s style is neoclassical, echoing a national trend that sought to idealize the common soldier through timeless forms. But its placement—at a public corner in a city central to the state’s formation—makes it more than generic tribute. It is an architectural claim on memory: a statement that the Union cause was not just victorious but virtuous.

Other communities followed suit. Stone markers appeared in county seats; tablets were placed in courthouses; occasionally, cemeteries received cast-iron plaques or engraved steles. These objects created a vernacular of visual mourning. They were not elaborate—they lacked the allegorical flourishes of major Eastern memorials—but they served their purpose. They gathered memory into form. And in doing so, they shaped how West Virginians saw themselves: loyal, tested, and enduring.

Three characteristics often marked these postwar monuments:

- Emphasis on the citizen-soldier over generals or abstract allegory

- Frequent use of local stone or iron from regional foundries

- Inscriptions that focused on statehood and loyalty to the Union

The Flag, the Seal, and the Uniform

In the years following the war, as West Virginia formalized its institutions and cultivated its distinct civic identity, visual symbols proliferated. The state flag was not adopted in its current form until 1929, but earlier versions circulated unofficially—bearing images of farmers, miners, and a large central boulder with crossed rifles and a liberty cap. Similarly, the Great Seal of West Virginia, finalized shortly after statehood, featured a woodsman and a farmer flanking that same boulder, meant to represent strength, resourcefulness, and independence.

These symbols appeared in murals, in courtroom plaques, on printed documents, and above schoolhouse blackboards. The visual language of the postwar state fused nature, labor, and defense. The rifle and pickaxe were as prominent as the scroll and gavel. Art, in this context, was not aesthetic decoration but a mode of reinforcement—of values, memory, and allegiance.

A Memory Set in Place

What the Civil War left behind in West Virginia was not a gallery of grand canvases but a landscape of memory embedded in terrain, stone, and modest illustration. The war created the state; the visual legacies it left behind gave that creation texture and meaning. Not every image was heroic, not every monument noble. But each helped fix the war’s presence in public consciousness—through ridge-top redoubts, courthouse tablets, family sketchbooks, and the bronze stillness of a soldier watching from a pedestal.

The visual culture of Civil War West Virginia was built not by academies or salons but by hands that fought, bled, surveyed, and remembered. Its works endure in quiet corners, understated but insistent, echoing the complex birth of a state forged in fire.

Chapter 4: Coal, Industry, and the Rise of Labor Imagery

The Machine Beneath the Mountain

No force shaped the visual identity of West Virginia more forcefully—or more persistently—than coal. In the decades following the Civil War, as railroads pushed deeper into the Appalachian interior, seams of bituminous coal emerged as both economic engine and cultural cornerstone. By the early 20th century, coal was not only fueling furnaces and factories across the United States—it was also generating a flood of visual material that would form the core of West Virginia’s industrial art history. From stark black-and-white photographs of underground labor to etched safety posters, union banners, and hand-painted signs nailed to company store walls, coal created an aesthetic of necessity, resilience, and conflict.

Coal Towns as Accidental Galleries

Coal camps were not built for beauty. They were utilitarian spaces, often hastily constructed and company-owned, populated by workers from the hollows of West Virginia and immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. But within their narrow streets and clapboard buildings, a rich visual culture emerged—not from artistic ambition, but from lived experience. Houses were painted in mineral greys and industrial greens. Posters lined the walls of local halls, warning of methane gas or encouraging “safe blasting.” Railroad signs were hand-lettered, fences scrawled with slogans, lunch pails marked with initials in white paint.

In this ecosystem, every surface was communicative. Even the uniform became part of the visual lexicon: the miner’s helmet, lamp, belt, and boots—a silhouette instantly recognizable, repeated across photos, sketches, and even early relief carvings found in miners’ lodges. Many workers decorated their helmets with union numbers or religious emblems. Function dictated form, but form rarely escaped symbolism.

Three visual motifs appeared frequently in coal town life:

- The crossed pick and shovel, sometimes carved into wooden signs or printed on circular union buttons

- Company scrip coins with engraved logos—miniature bas-reliefs of corporate identity

- Wall murals in union halls depicting underground tunnels and shafts, often in stark contrast to scenes of green hills above

Lewis Hine and the Power of Witness

In 1908, Lewis Hine arrived in the southern coalfields of West Virginia, part of a broader campaign by the National Child Labor Committee to document abuses in American industry. His photographs, among the most searing ever taken in the region, captured child miners as young as eight—bare-chested, coal-smudged, and weary-eyed—standing beside mule trains and track-mounted carts in the mines of Gary, WV.

These images were not aesthetic in the conventional sense; they were instruments of reform. But in their composition—frontal, unsparing, subtly symmetrical—they revealed the beginnings of a new visual vocabulary: labor as subject, toil as image. Hine’s photographs circulated nationally, transforming public perceptions of the coalfields and generating pressure for child labor reform. In doing so, they established coal not just as an economic issue, but a moral one—and art, in this context, became evidence.

What Hine saw in the shafts, others would come to see on the streets. His work laid the foundation for generations of social photographers who treated the West Virginia coalfields as a visual front line in a national story of labor, dignity, and exploitation.

Company Symbols and Industrial Branding

Industrial imagery did not flow only from critics and reformers. The coal companies themselves, paradoxically, produced much of the region’s visual culture. Company logos appeared on everything: scrip coins, metal lunch tokens, pay envelopes, trucks, hard hats, and advertisements. These icons—often designed with crisp, geometric economy—presented the corporate identity as clean, efficient, almost noble.

One notable example was the Consolidation Coal Company’s distinctive diamond logo, stamped into metal tokens and embossed on stock certificates. Even small independent outfits developed branding: circular sawblades framing mountains, a single flame symbolizing the “eternal burn” of coal, stylized letters forming pickaxes or seams.

This branding extended into architecture. The Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine—formerly the Phillips-Sprague Mine—retains signage and industrial markings that speak to a time when even utilitarian buildings carried an aesthetic fingerprint. Inside the mine today, visitors walk past restored wooden timbers and rail tracks that once bore company-mandated color coding and stenciled instructions. The design language was minimalist, but unmistakable.

In many ways, these corporate aesthetics paralleled the brutalist ethos of early Soviet poster art—functional, assertive, impersonal. Yet in the hills of Appalachia, this language was neither propagandist nor ideological. It was the language of control, of order imposed on chaos. Art in the service of production.

Labor Conflict as Visual Drama

Nowhere did the visual tension between worker and owner reach higher pitch than during the West Virginia Coal Wars. Between 1912 and 1921, a series of strikes, confrontations, and armed engagements turned mining country into a battleground. The Paint Creek–Cabin Creek Strike and the Battle of Blair Mountain—the latter involving thousands of armed miners clashing with private security and federal troops—produced not only dramatic headlines but iconic images.

While few formal artworks emerged from these events, photography again played a central role. Press photographers captured images of miners marching in formation, some in military surplus gear, others with hunting rifles slung over shoulders. Union banners bore hand-painted slogans—“We Want Justice,” “Organize or Starve”—rendered with immediacy and force. Photographs of the Logan County Courthouse, its windows shattered by bullets, or of militia camps in the woods, took on an almost cinematic quality. The line between documentation and symbolism blurred.

One lesser-known but telling artifact from this era is a hand-painted wooden sign discovered in a Kanawha Valley union hall, reading simply: “BREAD NOT BULLETS.” Its black lettering, faded but intact, was framed by crude line drawings of a miner’s pick and a loaf of bread. It was not art for galleries—but it was art for war.

The Domestic Side of Industrial Imagery

In 1946, photographer Russell Lee, working under federal commission, returned to West Virginia to document life in post-war coal towns. Unlike Hine, whose lens captured mostly the mines themselves, Lee turned his attention to kitchens, porches, schools, and general stores. His photographs are quieter, slower, often gently lit. A woman hangs laundry on a line stretched between two buildings. A boy carries a bucket of water over a cracked path. These images presented a kind of counterpoint to the grimness of labor—the rhythms of daily life shaped, but not destroyed, by industry.

What Lee’s photographs captured, intentionally or not, was a lived aesthetic: the way coal dust settled on everything, the sag of porches, the practical geometry of tin roofs and wooden braces. He photographed interiors with sparse decoration—perhaps a crucifix above the stove, a calendar with pastoral scenes, a union certificate in a wooden frame. It was art by presence, not design.

The Long Shadow of Industrial Iconography

Even as the coal industry declined in the late 20th century, the visual symbols it generated remained embedded in West Virginia’s identity. Painters returning to the region often depicted rusting coal tipples, abandoned carts, blackened landscapes reclaimed by green. Folk artists crafted miners from scrap metal. Quilters stitched black seams into tan cloth. In murals across town halls and museums, the helmeted miner remained central—sometimes heroic, sometimes ghostly.

What coal gave to West Virginia was not only employment and infrastructure, but iconography. It minted a visual currency of endurance, protest, survival, and sacrifice. It placed the human form underground and then brought it to light—in photos, in carvings, in signs that still hang in weathered store windows. And even where the mines are now quiet, their shapes remain visible—etched into the hills, and into the memory of a state that still sees its past through the lens of labor.

Chapter 5: Folk Traditions and Self-Taught Art

A Culture Shaped by Hands

Long before the advent of galleries, arts festivals, or formal institutions, the visual culture of West Virginia took root in a domestic sphere governed by necessity, repetition, and quiet ingenuity. The hills and hollows of the state fostered not only isolation, but continuity. Objects made by hand—quilts, baskets, carved utensils, and woven coverlets—were not considered “art” by their makers. Yet they reveal an aesthetic sensibility no less deliberate than the oils on canvas found in coastal cities. These were forms honed through memory and muscle, passed down without schooling, and shaped by what could be gathered, dyed, split, stitched, or turned with local materials.

The self-taught tradition in West Virginia is not an anomaly or a deviation from the mainstream of American art—it is its own lineage, sustained through centuries of labor, adaptation, and attention. In these works, technique and heritage are inseparable. And unlike movements governed by manifestos or critical theory, the folk traditions of this region arose organically, generation by generation, often without signatures or names.

Quilts as Geometry, Memory, and Survival

Among the most enduring and formally complex of West Virginia’s folk arts is quilting. Early settlers—particularly women of Scots-Irish and German descent—brought with them textile-making knowledge adapted from European traditions. In the mountainous terrain, far from manufactured goods or luxury imports, quilting took on a central domestic role. Scraps of worn clothing, flour sacks, and home-dyed calicos were pieced into geometric patterns that revealed both thrift and design intuition.

Patterns like Log Cabin, Bear’s Paw, and Ohio Star found particular resonance in the region. The Log Cabin quilt, for instance, echoed both the architecture of frontier homes and a symbolic sense of centeredness—each square starting from a core “hearth” and expanding outward. These quilts, often made during long winters or communal quilting bees, were not merely practical items. They were memory objects. Each scrap bore the ghost of a former shirt or dress. Each stitch carried the rhythm of a hand guided by repetition and care.

While most of these quilts were never exhibited during their makers’ lifetimes, they now reside in historical societies, heritage museums, and private collections across the state. The West Virginia Encyclopedia notes that some 19th-century coverlets rival the technical complexity of museum-grade tapestries, despite having been made on back-porch looms with no expectation of public display.

Wood, Clay, and Split Cane: Everyday Objects with Uncommon Character

Outside the textile arts, West Virginians produced a range of domestic tools and vessels that likewise straddle the line between function and form. Basketry, particularly from white oak and hickory, was widespread throughout the state. Techniques often varied by family or region, passed along through demonstration rather than instruction. Carved wooden spoons, butter molds, and toy animals exhibited an understated expressiveness—practical objects given personality.

Pottery, too, maintained a quiet but resilient presence in the hills. While not as commercially expansive as North Carolina’s pottery traditions, certain counties in West Virginia sustained multi-generational clay practices. Salt-glazed stoneware, often incised with initials, patterns, or dates, was common in farm households. Glazes were derived from wood ash or local minerals. Some pieces carried cobalt decoration—stylized vines or birds drawn with a sure, intuitive hand.

These objects tell a story not of grand design, but of rhythm: daily rhythms of use, seasonal rhythms of making, and lifelong rhythms of skill development untethered from institutions. They also reveal a kind of confidence—the confidence of someone who knows exactly how to carve a spoon that feels right in the hand, or weave a basket tight enough to carry a child to the field.

The Barn as Canvas: Quilt Blocks in Open Air

In the 21st century, a striking revival of folk aesthetic emerged across West Virginia’s back roads in the form of barn quilts—large, painted wooden panels affixed to barns, each featuring a geometric pattern drawn from traditional quilting designs. Though inspired by historical quilt motifs, barn quilts are a modern development, typically dating from the early 2000s. The movement began in neighboring Ohio and Kentucky, but found strong resonance in West Virginia, where the sight of a Mariner’s Compass or Shoofly Block mounted against weathered clapboard feels less like decoration and more like continuity.

These barn quilts function not only as public art but as place markers, memory objects scaled for visibility along winding rural routes. Each one typically references a family story, a historical figure, or a local legend. Together, they form patchwork trails of heritage—visual narratives spread across topography rather than locked in display cases. They are contemporary manifestations of an older instinct: to make meaning visible through form, to inscribe landscape with symbol.

Craft as Continuity, Not Nostalgia

It would be a mistake to view West Virginia’s craft traditions solely through the lens of nostalgia. While many techniques date back centuries, the act of making—by hand, without formal instruction—has remained vital well into the present. The 20th century witnessed a renewed institutional interest in these crafts, particularly during the Great Depression and again in the 1970s, when cultural preservation efforts brought greater attention to Appalachian folkways.

Workshops, guilds, and community fairs became more common. At places like the Tamarack Marketplace in Beckley, self-taught artisans display and sell their work with pride—pottery, woodturning, weaving, and handmade furniture judged by its skill rather than diploma. Here, tradition is not museumified; it is active, iterative, and sold by the piece.

Craftspeople today do not merely repeat old patterns. Many incorporate new techniques or adapt materials to suit modern demands. Some make functional replicas of historical tools; others push traditional forms toward sculpture. But what links them to the past is not style—it is the method: slow, deliberate, solitary, and grounded in material familiarity.

Three qualities continue to define the self-taught tradition in West Virginia:

- Material intimacy — a deep knowledge of local woods, fibers, and clays passed down through generations

- Functional refinement — the continuous honing of forms that must work as well as they look

- Cultural inheritance — a making-for-the-sake-of-continuity, not merely for sale or display

Micro-Narrative: The Weaver from Braxton County

In 1952, a woman named Hazel Jarvis, living near Sutton in Braxton County, wove coverlets on the same barn-loom her grandmother had used before the turn of the century. She worked by daylight, using hand-spun wool and vegetable dyes. Her patterns—mostly stripes and stylized florals—had no written record; she kept them in her head, adjusting each year based on memory, mood, or available yarn. When asked why she continued weaving in the age of store-bought blankets, she reportedly replied, “Mine don’t just warm the bed—they show who we are.”

That phrase, whether apocryphal or exact, distills the ethos of West Virginia’s folk art tradition. These works were never intended to impress strangers. They were made to live with, to outlast seasons, to mark family lineage without fanfare. Even today, in the echo of looms and the nick of carving tools, that impulse survives.

Chapter 6: The New Deal and the WPA in West Virginia

When Art Was a Job

The Great Depression ravaged West Virginia with a particular vengeance. Entire mining towns collapsed overnight. Unemployment soared. Hunger stalked the hollows. Against this backdrop of collapse, the federal government initiated one of the most ambitious cultural interventions in American history: the New Deal art programs. For the first time in the state’s history, art was not just encouraged—it was employed. Painters, sculptors, sign-makers, and craftsmen received federal paychecks, not to entertain elites but to enrich daily life. In post offices, courthouses, and civic buildings, West Virginians encountered visual art as part of their built environment—not imported from New York or Washington, but crafted by fellow citizens, often depicting scenes drawn from local life.

This was not merely a campaign to beautify public buildings. It was a redefinition of where art belonged, and who it belonged to.

The Arrival of Federal Art Programs

In 1933, the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) launched as a short-term experiment in employing artists during the depths of the Depression. West Virginia, despite its relative rural isolation, was included within Region 8—grouped with Pennsylvania—and quickly benefited from the national push to distribute commissions across every state. According to records, PWAP artists in this region produced dozens of works for public institutions: murals, bas-reliefs, oil paintings, and watercolors.

This initiative was expanded and institutionalized in 1935 under the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which included the Federal Art Project (FAP). For many towns across West Virginia, this was the first time a publicly funded artist ever walked through the door. The goal wasn’t abstraction or experimentation—it was legibility. The public had to recognize themselves in the art, and that meant mountains, mines, logging camps, harvests, and Main Streets. Artists painted what was already known—but never before framed.

Post Offices as Public Galleries

Nowhere did this vision manifest more clearly than in the post office mural program, administered by the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture (later known as the Section of Fine Arts). These murals were not WPA projects per se, but part of a parallel New Deal effort to integrate art into newly constructed federal buildings. Sixteen post offices across West Virginia received art commissions. Though modest in number, these murals reshaped the role of civic space: a place not only to collect mail but to confront memory, identity, and shared labor in paint.

In places like Point Pleasant, Mannington, and Welch, murals depicted coal miners, farmhands, loggers, and blacksmiths—always working, always grounded. They were often painted in a muted, realistic style influenced by American Regionalism. Many bore the imprint of Thomas Hart Benton’s curved forms and narrative compositions, though executed by lesser-known artists.

These murals often presented a vision of solidarity without sentimentality. In Welch, one mural shows miners descending into a darkened shaft, their faces calm but determined. In another, women harvest grain in careful procession. The dignity of labor was the message—but so was endurance. West Virginians, long skeptical of outside authority, found in these works something surprisingly familiar: recognition, not instruction.

The Elkins Murals: Dual Portraits of Identity

Perhaps the most compelling example of New Deal mural work in the state comes from the United States Forest Service building in Elkins. Built between 1936 and 1938, the building received two murals in 1939 by Stevan Dohanos, a Hungarian-American painter who would later become known for his cover illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post. His murals, titled Forest Service and Mining Village, hang in visual dialogue with each other.

Forest Service celebrates conservation: men planting trees, measuring timber, and surveying terrain—framed by distant ridgelines and clouded skies. It’s an image of stewardship, scientific progress, and harmony between labor and nature.

By contrast, Mining Village shows miners clustered near simple wooden homes, under a sky less generous. There’s tension in their posture, heaviness in their gait. Smoke curls from the chimneys but the mood is opaque. This isn’t condemnation, but complexity. Together, the two murals express the double nature of West Virginia’s relationship with the land: one as caretaker, one as extractor.

In a single building, the duality of the state’s identity was put into paint—not for tourists, but for clerks, rangers, and citizens walking the halls each day.

Artists as Workers, Not Outsiders

Unlike later government-funded art projects, which sometimes imported talent from metropolitan centers, the New Deal programs encouraged hiring local or regionally familiar artists. This led to a striking result: West Virginians began to see artists not as bohemians or outsiders, but as fellow workers.

In Clarksburg, one artist known only through his surviving watercolors painted scenes of back porches, barn dances, and freight trains in snow. In Charleston, a team of WPA artists produced wall-mounted maps, painted signs, and schoolroom illustrations with careful draftsmanship. Their work was not signed or celebrated—but it filled public buildings with visual structure and coherence.

One little-known WPA program even included instruction in handcrafts—teaching woodworking, weaving, and ceramics in rural communities. These efforts connected seamlessly with the state’s existing folk traditions. The line between craft and art blurred, and for the first time, both were federally supported.

A Micro-Narrative: The Teacher Turned Muralist

In 1936, a high school art teacher from Parkersburg named Martha Hedrick was hired under the WPA to design visual materials for local schools. Initially tasked with making educational posters, she proposed a mural series instead—panels that would show the history of the Ohio River Valley, from native settlements to steamboat trade to modern bridges. Working in tempera on canvas affixed to plaster walls, she painted by night in the school gymnasium, using former students as figure models.

Her murals, long painted over, were rediscovered in the 1990s during renovation. Their revival tells not only the story of her hand, but of the era that gave her work purpose. Hedrick was not a gallery painter. She was a civil servant, using brush and pigment to turn civic walls into vessels of continuity.

The New Role of the State as Patron

The WPA and related programs did more than temporarily employ artists—they altered the role of government in cultural life. For the first time, the state functioned as patron of the arts not to elevate style or support innovation, but to provide dignity through visibility. A miner, teacher, or farmer could walk into a courthouse and see their life rendered in oil. This democratization of subject matter, supported by public funds, created a model for regional art that extended long after the programs ended in the early 1940s.

When funding ceased, many of the works remained. Some were lost or painted over, but others endured—quietly embedded in post offices, government buildings, and public schools across the state. They became fixtures, no longer revolutionary but familiar.

And while the aesthetic of these works—realist, grounded, narrative—would fall out of fashion in postwar art circles, they left behind something more permanent: a belief that West Virginia’s landscapes and laborers were worthy of depiction, and that art was not a luxury, but a job well done.

Chapter 7: The Founding of the Huntington and Charleston Museums

From Artifacts to Institutions

For much of its early history, West Virginia’s visual culture lived in private homes, public murals, churches, and the unassuming spaces of everyday life. There were few formal galleries, and even fewer collections. Art—when it appeared in public—was often utilitarian, decorative, or government-sponsored. But by the middle of the 20th century, this began to change. Two institutions in particular emerged as anchors of the state’s artistic infrastructure: the West Virginia State Museum in Charleston and the Huntington Museum of Art. Their founding marked a shift from scattered preservation to structured curation—from fragments of visual history to galleries, catalogues, and exhibitions. The rise of these museums changed how West Virginians saw their past, and how they imagined their place in the wider world of art.

Charleston’s State Museum: A Cabinet of the Mountain Commonwealth

Though its formal beginnings trace to 1905, the West Virginia State Museum originated with a cabinet of curiosities. In 1890, the state’s Department of Archives and History began collecting objects tied to West Virginia’s founding, natural environment, and early settlement. At first, these were not works of fine art—more often they were minerals, military relics, geological samples, and domestic tools. But together they formed a visual vocabulary of the state’s identity: rugged, resource-rich, self-reliant.

By the early 20th century, the museum grew into a more structured institution. Located in Charleston, and closely tied to the State Capitol complex, the museum evolved from historical storage into a place of interpretation. Dioramas depicted frontier cabins and logging camps. Murals were commissioned to represent key events in the state’s history. Paintings began to appear—not portraits of elites, but scenes of Appalachian life, mining, industry, and community. The museum’s purpose was not artistic innovation, but coherence: to unify West Virginia’s past into a viewable whole.

One of the museum’s early visual focal points was its large, multi-gallery timeline—a curated journey through the prehistoric, colonial, and industrial eras of the state. Although many of the displayed works were anonymous or utilitarian, the effect was immersive. Visitors encountered fragments of pottery, fragments of war, fragments of work. In many ways, the State Museum operated as a physical counterpart to the New Deal ethos—it made public the lives of ordinary people and treated their labor as worthy of commemoration.

Huntington’s Cultural Ascent: From Industrial Hub to Art Center

In contrast to Charleston’s broad historical mission, the Huntington Museum of Art emerged with a focused cultural goal: to bring fine art to a region better known for shipping, manufacturing, and coal. The museum’s roots were private. Herbert Fitzpatrick, a prominent attorney and collector, donated land and works from his personal collection in the 1940s, envisioning a space where art and education could coexist in a setting open to all.

By the time it officially opened to the public in 1952 as the Huntington Galleries, the institution represented a striking development in the state’s cultural life. Its early collections included American and European paintings, glass, and decorative objects. Unlike Charleston’s state-sponsored museum, Huntington’s was privately founded but public-facing. It combined connoisseurship with civic generosity.

From the start, the museum distinguished itself by looking outward and inward simultaneously. It hosted exhibitions from national collections while also nurturing regional artists. It collected 19th-century landscape painting alongside contemporary Appalachian work. Its studio spaces and educational programs brought in students, hobbyists, and young artists—making it a living institution rather than a static repository.

Three elements defined the Huntington Museum’s early impact:

- A rare balance of international and regional focus in acquisitions

- An enduring emphasis on art education, with classes and lectures from the 1950s onward

- A deliberate architectural setting that combined modernism with openness to the wooded landscape around it

Glass, Landscape, and Local Identity

Perhaps no part of the Huntington Museum’s collection better illustrates its regional intelligence than its holdings in glass. Given West Virginia’s long history with glassmaking—from Blenko to smaller, now-vanished factories—the inclusion of glass as a serious artistic medium was both appropriate and forward-looking. Pieces ranged from early pressed-glass patterns to studio glass works by contemporary artisans. By framing glass as both craft and art, the museum elevated a local industry into a cultural asset.

Similarly, the museum’s strong holdings in American landscape painting helped reinforce a sense of continuity between West Virginia’s visual environment and the broader tradition of American art. Paintings by 19th-century artists—some depicting the Alleghenies or imagined versions of Appalachia—were exhibited in the same halls as regional modernists and realist painters working with more intimate or industrial subject matter.

This fusion of fine art and regional craft offered visitors something rare: a museum that neither pandered to urban taste nor retreated into provincialism.

Micro-Narrative: A Painting Comes Home

In the mid-1960s, a painting long thought lost resurfaced in a Wheeling antique store: an 1880s oil depicting the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers, framed by autumnal trees and steamboats trailing white smoke. The painter was an amateur—name unsigned—but the technique suggested training and patience. The Huntington Museum acquired it, not for its artistic brilliance, but for its resonance. The river was no abstraction; it was history in motion. The museum placed it in a gallery alongside modernist works from the 1950s, drawing a silent line between past and present, region and experiment.

Visitors paused longer before the riverscape than before the more critically celebrated works nearby. It wasn’t just nostalgia—it was recognition.

From Collection to Conversation

Both the State Museum and the Huntington Museum of Art played different but complementary roles in shaping how West Virginia saw itself culturally. Charleston’s museum presented the sweep of historical continuity: fossils, muskets, quilts, locomotives. Huntington’s offered refinement and encounter: light falling on glass, brushstroke meeting sky, color lifting off canvas.

Together, they helped move West Virginia’s art from the walls of courthouses and the porches of cabins into curated space—without stripping it of its meaning. They gave permanence to what had often been ephemeral. And they created a foundation for the next generation of artists and audiences, proving that art in the Mountain State could be both rooted and ambitious.

Chapter 8: The Appalachian Aesthetic in the Mid-20th Century

A Mountain Language in Paint

By the middle of the 20th century, as American art veered increasingly toward abstraction, minimalism, and urban conceptualism, a quieter current ran through West Virginia. Here, artists continued to wrestle with landscape, labor, and identity using forms that were resolutely grounded—representational, textured, regional. What emerged during this period was not a single school or manifesto, but something more durable: an aesthetic language rooted in the Appalachian experience. It rejected spectacle in favor of solidity, turning away from the city’s noise to capture the emotional topography of the hills, towns, and people of the Mountain State.

This Appalachian aesthetic wasn’t retrograde. It was defiant. It carved its own path through mid-century art by asserting that place mattered—that fidelity to one’s surroundings could yield work as rich and honest as anything hanging in the Whitney or the Art Institute of Chicago.

Localism Without Provincialism

The idea of “Appalachian art” had long existed, but it was often flattened into stereotypes—corncob pipes, log cabins, or sentimental mountain scenes. The artists working in mid-century West Virginia dismantled those clichés not by rejecting the region, but by representing it with precision and complexity. Their paintings, drawings, and prints often featured landscapes and faces familiar to anyone from the region. But these were not folkloric illustrations. They were rigorous works: compositions carefully structured, colors modulated with restraint, and gestures observed from life.

This was not academic realism, nor was it nostalgia. It was regionalism with its sleeves rolled up. And it owed something to the earlier example of American Regionalist painters—Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood—whose influence lingered after their national prominence had faded. In West Virginia, that influence manifested not as imitation, but as permission: a license to treat the local as worthy of serious attention.

Painters of the Working Landscape

For many mid-century West Virginian artists, the landscape was inseparable from labor. Ridges and streams were not just aesthetic forms; they were routes for timber, coal, and cattle. The best of these works revealed a deep sensitivity to human presence—sometimes explicit, sometimes merely suggested. A boot track in snow. A barn half-obscured by fog. A pair of miners walking out of frame, headlamps off.

Such images could be found in the collections of the newly opened Huntington Museum of Art, which, from its founding in 1952, began collecting regional works alongside national and European paintings. The museum’s exhibitions provided the first formal space in the state for the serious display of Appalachian art—not as curiosity or folklore, but as part of the American canon.

Meanwhile, the West Virginia State Museum continued to collect and display works that straddled the line between historical documentation and visual art. These included drawings of mine operations, watercolor studies of small-town streets, and portraits of workers in rail yards and machine shops. Though often unsigned, these pieces recorded a visual truth: that art in West Virginia did not have to rise above its context to find value—it could burrow deeper into it.

A Mid-Century Imprint: The Weight of Realism

Even as New York dominated national conversations with Abstract Expressionism, West Virginian artists remained committed to the figurative. Their palettes may have shifted—dustier blues, earthier reds, subdued ochres—but their focus stayed on scenes that meant something in the world they inhabited.

The choice was aesthetic, but also ethical. To abstract a coal miner’s burden into gesture or splatter would have felt evasive. Instead, mid-century painters rendered the weight of the helmet, the slope of the tunnel, the set of the shoulders. Likewise, a hillside was not simply an arrangement of green—it was a site of memory, of labor, of collapse.

There was no need to invent drama. The mountains provided it. Fog over a hollow. A storm breaking behind a grain silo. A man standing on a ridge, arms folded, watching nothing in particular.

Micro-Narrative: A Landscape for No One

In 1964, a painting arrived unceremoniously at a regional exhibition hosted by the Huntington Museum of Art. The artist was a high school teacher from Raleigh County, and the work showed a mountainside stripped of its timber—muddy, raw, littered with broken stumps. No figures were present. The sky was the color of slate. There was no title. When asked, the artist said simply: “It’s what’s there when they leave.”

Though the piece won no award and was never acquired, it haunted those who saw it. For years, instructors in nearby schools referenced it when teaching perspective and mood. It captured something essential about the Appalachian aesthetic: beauty not as ideal, but as persistence.

The Self-Taught Thread

Alongside these academically trained artists, self-taught creators in rural West Virginia continued to produce works that mirrored—often unconsciously—the formal concerns of their trained counterparts. Carved wooden reliefs, stitched narrative quilts, and painted tableaus of mountain life often featured the same themes: labor, weather, topography, memory.

While these works were rarely framed or exhibited in formal settings during the period, they formed a shadow gallery that paralleled the professional art world. In many cases, self-taught artists had greater freedom: to blend scale, perspective, and story; to combine religious vision with family history; to place a chicken coop beside a burning bush without irony.

By the 1980s and 1990s, museums would begin to embrace this self-taught tradition more seriously. But in the mid-century, it simply persisted—quiet, generative, often unsigned.

Appalachia on Its Own Terms

The Appalachian aesthetic of the mid-20th century did not beg recognition from coastal critics. It remained rooted in place, confident in its modesty. Its painters, carvers, and weavers did not seek to be revolutionary—they sought to be truthful. And that truth, rendered in mountain forms, bowed rooflines, and long shadows, left an imprint that younger artists would later return to.

In the work of sculptor Jamie Lester—born 1974 in Morgantown—one finds echoes of that earlier aesthetic. Lester’s sculptures, though contemporary, carry a similar weight: grounded in human form, shaped by memory, and attentive to the silent dignity of work. His bronze figures, public commissions, and portrait busts feel less like departures from mid-century predecessors than fulfillments.

The mountain continues to exert pressure. Artists from the region still paint, carve, and photograph with it in mind. And whether explicitly acknowledged or quietly inherited, the mid-century Appalachian aesthetic remains foundational—proof that localism, pursued with discipline, can produce art of lasting consequence.

Chapter 9: Clay, Glass, and the Ceramics Tradition

Craft in Fire: How the Mountain Shaped Its Materials

No medium reflects the material identity of West Virginia more directly than glass and clay. Both are born of the land—sand, minerals, earth, fire—and in the hands of its workers and artists, both became not only industries, but traditions. The state’s long and varied history with glassmaking and ceramics reveals a deep link between geology and creativity, between resource and form. From 19th-century industrial furnaces to 20th-century designer studios, West Virginia’s legacy in these media offers some of the clearest expressions of how art and craft can emerge from a specific place, shaped as much by natural circumstance as by human intent.

Glass and ceramics in West Virginia never existed in isolation from work. They were trades. But in their best expressions, they transcended function to become a distinct aesthetic language: hard, luminous, enduring.

The Groundwork: Why West Virginia Became a Glass State

The rise of the glass industry in West Virginia was no accident. The region’s natural resources offered an ideal combination: abundant silica sand, vast reserves of natural gas and coal to fuel furnaces, and a central location with access to major railways and rivers. By the late 1800s, small glassworks dotted the state—making bottles, jars, lamp chimneys, and architectural glass.

What began as utility quickly expanded into refinement. Companies such as the Seneca Glass Company in Morgantown, founded in 1897, produced high-quality lead glass, often hand-cut and etched, for use in fine tableware. Seneca’s workers were highly skilled craftsmen—many European immigrants—trained in old-world methods but working in American rhythms. Their pieces bore a quiet elegance: heavy bases, precise beveling, understated patterns.

By the early 20th century, West Virginia was home to hundreds of glass manufacturers. Not all survived the Depression or the rise of automation, but the visual legacy of their work remains—crystal pitchers, fluted vases, pressed-glass compotes—each reflecting light differently depending on who made it, and when.

Blenko and the Transformation of Utility into Design

In 1921, the Blenko Glass Company moved its operations to Milton, West Virginia. Originally focused on stained glass for churches and public buildings, Blenko shifted in the 1930s toward tableware and decorative glass. But it was the postwar period that truly transformed the company—and, by extension, the perception of West Virginia glass.

In 1947, Blenko hired Winslow Anderson, a formally trained designer who introduced modernist principles to the company’s production. Anderson brought with him a vision of simplicity and form. His pieces were bold: vibrant colors, exaggerated curves, organic silhouettes. With Anderson and his successors, Blenko glass entered the world of design art, appearing in galleries and museum stores—not just on kitchen shelves.

Three characteristics defined the Blenko aesthetic under Anderson:

- Thick, sculptural forms that emphasized weight and contour

- Bright, saturated colors drawn from mid-century modern palettes

- A visible “handmade” quality—tool marks, slight asymmetries, and wavering surfaces that spoke of individual creation

These pieces were still made by teams of workers in hot shops, using traditional hand-blowing techniques. But their end use had changed. They were no longer simply for serving—now they were for display, for collecting, for understanding glass as visual and tactile sculpture.

The Ceramics of Necessity and the Ceramics of Expression

While glass dominated West Virginia’s industrial art identity, ceramics quietly persisted—less visible, but no less important. From the early 1800s, settlers produced stoneware and earthenware for personal and community use: crocks, jugs, bowls, and baking dishes. Clay was abundant, and many families had access to simple wheel setups and communal kilns. Most pieces were glazed in salt, ash, or slip, with only minimal decoration—perhaps a stamped maker’s mark or incised flourish.

In the 20th century, this utilitarian tradition began to evolve under the influence of university programs, craft revival movements, and the broader studio pottery trend in American art. Institutions such as West Virginia University and Marshall University developed strong ceramics departments, teaching wheel-throwing, glaze chemistry, and kiln construction. The state’s long history with clay provided fertile ground for these programs. Students were often descendants of potters or miners—accustomed to working with their hands, respectful of process.

Studio potters in the 1960s and 1970s took up local traditions and expanded them. They retained the rugged forms and earth-tone glazes of traditional Appalachian pottery but began experimenting with scale, texture, and surface. Some incorporated sgraffito carving or used wood-fired kilns to produce unpredictable glaze effects. Their work began appearing at regional fairs, craft festivals, and galleries—part of the broader movement that recognized American craft as art.

Museums and Preservation: From Production to Display

As the commercial glass industry declined in the late 20th century, institutions began to preserve its history. In 1993, the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia was founded in Weston. Its mission: to document and exhibit the products and processes of the state’s glassmaking legacy. With thousands of objects—ranging from pressed tumblers to elaborate art glass—the museum offers a visual history of the craft, charting changes in style, technique, and public taste.

Meanwhile, institutions like the Huntington Museum of Art and the West Virginia State Museum added glass and ceramic works to their permanent collections, not as artifacts of industry alone but as part of the state’s artistic heritage. By doing so, they signaled a shift in perception. What had once been anonymous labor was now understood as creative expression.

Even smaller towns began to celebrate their glass histories. Former factory buildings were converted into arts centers. Annual festivals featured live glass-blowing demonstrations. The glassblower, once a factory worker, now stood center stage—his pipe and gather a kind of performance, his product sold as heirloom rather than commodity.

Micro-Narrative: A Vase for a Wedding

In 1954, a Blenko glassblower in Milton created a custom cobalt-blue vase as a wedding gift for his niece. It was a simple cylinder with a flared lip, faintly mottled by air bubbles. The couple placed it in their front window, where it caught the morning light for over sixty years. In 2020, after both had passed, the vase was donated to the Museum of American Glass. The curator who received it said it was one of the “most perfect imperfected” examples of mid-century hand-blown design—a piece made with love, not for sale, that nonetheless captured the entire arc of West Virginia’s glass tradition: family, labor, form, and light.

The Material Memory of the Mountain

Clay and glass, more than other media, record the gestures of their makers. Every swirl in a ceramic bowl, every ripple in blown glass, holds a trace of movement, breath, and touch. In West Virginia, these materials are not imported—they are dug, gathered, melted, and shaped from the state’s own geology. That intimacy with source gives the resulting objects their gravity.

Whether produced in factory rows, university studios, or backyard kilns, the ceramics and glassworks of West Virginia tell a story of transformation—not just of earth into object, but of trade into art. And in a region where history is often carried forward by hand, that transformation continues to shine and endure.

Chapter 10: University Studios and the Emergence of Contemporary Art

From Hollow to Studio: Art as Discipline and Departure

As West Virginia entered the final decades of the 20th century, its visual culture began to shift. The rhythms of folk craft, the legacy of New Deal murals, and the realism of Appalachian regionalism still held influence—but a new element emerged: the art school. For the first time, large numbers of West Virginians were not learning to paint, sculpt, or print from parents or tradesmen, but from professors. Art became a course of study. The studio moved from the back porch to the classroom, and with it came new ideas, materials, and ambitions.

Two institutions led this evolution: West Virginia University in Morgantown and Marshall University in Huntington. Their studios, faculty, and galleries offered something previously rare in the state—structured exposure to contemporary art movements, cross-disciplinary experimentation, and critical feedback. In these spaces, West Virginian artists began to engage not only with their immediate surroundings but with global conversations in sculpture, abstraction, conceptual art, and digital media.

West Virginia University: An Appalachian Studio Laboratory

West Virginia University (WVU), the state’s flagship institution, had long supported art instruction, but by the 1970s and 1980s, its School of Art and Design had matured into a center of serious artistic inquiry. Housed in the Canady Creative Arts Center, WVU offered degrees in painting, sculpture, ceramics, photography, graphic design, and printmaking, supported by studios equipped for both traditional and experimental work.

What set WVU apart was its ability to straddle local identity and international relevance. In printmaking studios, students carved linoleum blocks bearing Appalachian motifs—rail lines, pickaxes, timber scenes—but printed them in bold, modernist forms. Ceramics students studied traditional Appalachian salt glazing, but then pursued alternative firing methods like raku or soda vapor. Photography students captured the geometry of decaying industrial spaces, blending realism with abstraction. Faculty often came from far beyond the region, but brought a respect for place, encouraging students to draw on their own geography rather than mimic distant trends.

This hybrid model—local content, formal rigor, and conceptual openness—produced a generation of artists who were grounded but unbounded. Their works were not shackled to the state’s history, but neither did they reject it. They translated mountain forms into metal, rendered folk memory in latex and pigment, and questioned representation without discarding it.

Marshall University: Urban Edge and Studio Presence

Marshall University, located in Huntington, offered a parallel but distinctive path. With the opening of the Visual Arts Center in 2013—housed in a renovated department store in the city’s historic downtown—the university expanded its arts education into the public sphere. Students worked in bright studios that overlooked city streets, anchoring their education in the rhythms of urban life.

Marshall’s program emphasized technical fluency and cross-disciplinary dialogue. Painting and drawing students shared gallery walls with sculptors and ceramicists; digital artists exhibited alongside woodworkers and fiber designers. The surrounding city—once a rail and industrial hub—provided an ambient texture of decay, resilience, and regeneration that filtered into the work.

Here, too, regional identity was not imposed, but ever-present. Students painted trains, rivers, diners, and empty lots. They incorporated coal dust into sculpture, photographed family farms as performance spaces, reinterpreted county-fair ribbons as conceptual installations. Their work often carried a quiet seriousness—less inclined toward irony, more inclined toward memory and form.

Three common traits emerged from Marshall’s contemporary studio culture:

- A preference for material experimentation over theoretical posturing

- A strong engagement with West Virginia’s urban-industrial aesthetic

- A commitment to public exhibition as a form of dialogue, not just presentation

Beyond Academia: Monongalia Arts Center and Community Practice

Not all contemporary art in West Virginia passed through the university gate. Community-based institutions like the Monongalia Arts Center (MAC) in Morgantown provided space for emerging and self-taught artists to explore contemporary modes without academic framing. Opened in 1978, MAC hosted exhibitions, performances, workshops, and installations, often with a rawness and immediacy absent from more curated university shows.

At MAC, one might encounter a collage series made from coal-company newsletters, an audio installation using field recordings of mining equipment, or a set of photographs documenting rural garages repurposed as artist studios. These works were rarely commercial and often ephemeral. But they offered an essential counterpoint to institutional production—reminding viewers that contemporary art in West Virginia could be experimental without being imported.

MAC also functioned as a node of regional exchange. Artists from Pittsburgh, Lexington, and Asheville often showed work there, cross-pollinating Appalachia’s overlapping creative circles. In a state better known for its topographic isolation, MAC operated like a clearinghouse of ideas—local in origin, regional in circulation.

Micro-Narrative: A Printmaker’s Fault Line

In 1991, a WVU printmaking student named Carl Madison exhibited a linocut triptych titled “Seam” in the university’s gallery. It depicted a cross-section of mountain strata, each layer patterned differently: trees in the topsoil, miners in the coal seam, and ghosts in the bedrock. The imagery was dense, rhythmic, almost abstract. But it told a clear story: labor above, below, and beneath.

The triptych was acquired by a small community college in the southern coalfields, where it now hangs outside a geology classroom. Students pass it daily. It’s not famous, but it’s faithful—to both form and place.

Curriculum as Catalyst

By the 2000s, WVU and Marshall had expanded their programs to include digital media, installation, performance, and interdisciplinary practices. Students built projection pieces in abandoned buildings. They used GIS data to generate paintings. They turned grant-funded research into outdoor sculptural interventions. And alongside this, traditional skills were not abandoned: stone carving, wheel-thrown ceramics, hand-built frames and darkroom photography remained embedded in the curriculum.

In 2019, WVU launched the first undergraduate degree in Technical Art History in the United States—a program that merged studio practice with material science, conservation, and critical analysis. Its existence signals not only the university’s scholarly commitment, but the growing sense that West Virginia’s own artistic past requires sustained, technical attention. Not everything can be passed down by intuition alone. Some things must be studied, restored, preserved—and then taught anew.

A Different Kind of Contemporary

Contemporary art in West Virginia is not loud. It does not proclaim novelty for its own sake. Instead, it often folds innovation into memory, new technique into old form. University studios have enabled this evolution—not by rejecting the past, but by providing the tools to reframe it.

Artists trained in these institutions work today in sculpture, new media, socially engaged practice, and performance. But many still draw from the same wells: fog over the ridge, the silhouette of a barn, the feel of coal dust between fingers. The mountain, even now, remains a kind of studio wall—its outline informing what happens inside.

Chapter 11: The Landscape Reimagined in the 21st Century

The Return to Form, the Shift in Vision

In the 21st century, West Virginia artists have returned again and again to the landscape—not as a backdrop or a symbol, but as a subject in flux. The mountains no longer stand only for permanence. The forests are no longer only scenic. Rivers, hollows, ridges, strip-mines, floodplains, culverts, and weed-laced parking lots: these have become the new frontier of visual attention. Contemporary artists in the Mountain State have not abandoned realism or regionalism—they have reworked them, layering ecological observation, historical memory, and subtle personal commentary into their depictions of place.

What has emerged is a landscape tradition that neither romanticizes nor rejects the region’s past. It interrogates it, walks through it, sits with it. Painters, sculptors, and mixed-media artists across West Virginia have taken the old tools—brushes, sketchbooks, casts, cameras—and aimed them not only at mountains and trees, but at what lies in between: the lived, altered, threatened terrain of home.

Plein Air with a Purpose

One of the most visible manifestations of this shift is the quiet resurgence of plein air painting. Across the state, artists have taken to woods, fields, and backroads to paint directly from observation. But this isn’t a revival of 19th-century Romanticism. Instead, these artists seek clarity and specificity: not the idealized valley but the collapsing barn, the frayed power lines, the light off a metal guardrail at dusk.

In this context, the act of painting becomes more than technique—it becomes attention. The artist documents not just what is beautiful, but what is vanishing, what is changing, what is overlooked. This shift marks a maturation of the landscape tradition in West Virginia: no longer confined to the grand or the picturesque, it now includes the intimate and the imperiled.

A new generation of artists has embraced this ethic. Painters like Rosalie Haizlett, who trained as a naturalist, render forest scenes with a botanist’s precision and a storyteller’s eye. Her watercolors of mushrooms, lichens, streambeds, and forest-edge flora carry both scientific detail and gentle lyricism. Her work is landscape art not from the ridgeline but from the understory—low, close, aware of what’s at risk.

Jamie Lester and the Human Landscape