The Vienna Biedermeier period was a unique artistic and cultural movement that flourished in Austria and Central Europe between 1815 and 1848. It reflected the values of the growing middle class, focusing on sentimentality, domestic life, and a restrained aesthetic. The style emerged in response to political repression under the Austrian Empire, where censorship discouraged grand historical or revolutionary themes. Instead, artists, designers, and writers turned to intimate subjects, creating works that emphasized quiet beauty, realism, and moral virtue. Though often overlooked in favor of more dramatic artistic movements, Biedermeier left a lasting impact on European art, furniture design, and interior aesthetics.

Introduction to Vienna Biedermeier

The Biedermeier style developed in Austria following the Napoleonic Wars, flourishing in the peaceful but politically repressive era that followed the Congress of Vienna in 1815. With the Austrian Empire under strict conservative rule, artistic expression turned away from political and heroic themes and instead embraced domestic life, nostalgia, and understated elegance. The movement was most prominent between 1815 and 1848, the period in which Austria’s rigid censorship laws limited the scope of creative works. This led artists to focus on the simple joys of everyday life, capturing moments of family, childhood, and nature with warmth and sincerity.

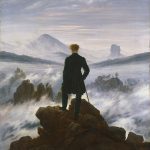

Biedermeier art was distinct from the grand styles of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, favoring smaller compositions with a more intimate perspective. Unlike the mythological or historical themes found in previous artistic traditions, Biedermeier paintings featured subjects such as well-dressed families in quiet interiors, children playing in sunlit rooms, or peaceful landscapes without dramatic effects. This made the movement particularly appealing to the rising bourgeoisie, who sought art that reflected their values and lifestyles. Artists achieved remarkable detail and clarity, using soft lighting and muted colors to enhance the sense of tranquility.

The movement extended beyond painting to include furniture, literature, and decorative arts, making it one of the first artistic trends to influence multiple disciplines. Biedermeier furniture, for instance, was known for its simplicity, functionality, and fine craftsmanship, favoring clean lines over excessive ornamentation. Literature followed similar principles, with authors like Adalbert Stifter and Franz Grillparzer writing about moral virtue and personal introspection rather than heroic exploits. This comprehensive aesthetic reflected the ideals of a class that valued refinement, modesty, and practicality in all aspects of life.

While Biedermeier was primarily a middle-class movement, it also found support among aristocrats who appreciated its elegant restraint. The period saw an increase in demand for art that was accessible and relatable, as people sought beauty within their homes rather than in grand public monuments. Over time, Biedermeier’s focus on realism and sincerity influenced later artistic movements, particularly Realism and Impressionism. Though the movement faded after 1848, its legacy endured in European culture, especially in furniture design and portrait painting.

The Political and Social Context of Biedermeier Art

The political environment of post-Napoleonic Europe played a crucial role in shaping the themes and style of Biedermeier art. Following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the Congress of Vienna sought to restore stability by reinstating monarchies and suppressing revolutionary ideas. In Austria, Prince Klemens von Metternich led an authoritarian regime that imposed strict censorship on the press, arts, and public discourse. Any form of political dissent was swiftly repressed, forcing artists and writers to avoid controversial subjects. As a result, creative expression turned inward, focusing on personal life, morality, and the comforting routines of home.

The Austrian government’s control over intellectual and artistic output meant that large-scale historical or politically charged works were discouraged. Instead of grand allegories or depictions of revolutionary heroes, artists painted serene family portraits, quiet interiors, and picturesque rural scenes. The absence of dramatic themes in Biedermeier art was not due to a lack of skill or ambition but rather to the necessity of working within the boundaries imposed by the authorities. This restriction led to an aesthetic that prized subtlety, sentimentality, and an appreciation for the beauty of everyday life.

At the same time, the early 19th century saw the emergence of a prosperous middle class, which became the primary patron of Biedermeier art and design. As industrialization progressed, the bourgeoisie grew in economic and social influence, seeking to surround themselves with tasteful yet modest works of art. They favored paintings that reflected their own lives—peaceful domestic scenes, well-mannered children, and refined interiors. Unlike the aristocracy, which had traditionally commissioned grand mythological and historical paintings, the middle class wanted art that was intimate, personal, and reflective of their values.

Technological advancements also contributed to the spread of Biedermeier aesthetics, particularly in the printing and publishing industries. The rise of affordable lithographs, woodcuts, and illustrated books allowed for the mass production of art, making it more widely available than ever before. This democratization of art meant that even those who could not afford original paintings could still enjoy Biedermeier imagery in printed form. The period also saw the rise of illustrated magazines and decorative prints, further embedding the style into everyday life.

Characteristics of Biedermeier Art and Its Unique Aesthetic

Biedermeier art is distinguished by its focus on realism, domesticity, and restrained elegance, setting it apart from the more dramatic artistic movements of the time. Rather than depicting mythological or heroic subjects, Biedermeier painters turned to quiet moments of family life, portraits of well-dressed individuals, and idyllic landscapes. The compositions were often intimate, inviting the viewer into the scene as though they were part of the domestic space. This emphasis on everyday moments created a sense of familiarity and warmth, making the art accessible to a broad audience.

One of the defining features of Biedermeier painting is its carefully controlled use of color and light. Artists employed soft, natural lighting to enhance the realistic quality of their works, avoiding the dramatic contrasts typical of Baroque or Romantic art. Colors were often muted but rich, creating a sense of depth and subtle beauty. The meticulous rendering of fabrics, furniture, and facial expressions contributed to the overall sense of calm and refinement. This precision reflected the values of the time, as the middle class prized both craftsmanship and emotional sincerity.

Realism played a crucial role in Biedermeier’s aesthetic, with artists striving for a high level of detail and accuracy in their work. Portraiture became particularly significant, capturing not only the likeness but also the personality and character of the sitter. Families were often depicted in comfortable, elegant surroundings, highlighting the importance of home and stability. Scenes of children playing, women engaged in domestic tasks, or men reading in quiet study rooms reinforced the period’s emphasis on virtue, order, and respectability.

Another key characteristic of Biedermeier art was its modest scale and composition. Unlike grand historical paintings, which were meant to be displayed in palaces or churches, Biedermeier artworks were designed for private homes. This shift in scale and subject matter aligned with the changing social dynamics of the time, as more people sought art that could be integrated into daily life. The movement’s aesthetic balance between realism and sentimentality made it enduringly popular, even as artistic trends evolved in later decades.

The Decline of Biedermeier and Its Later Revival

The Biedermeier movement began to fade in the late 1840s as political and social upheaval reshaped Europe. The Revolutions of 1848, which spread across the continent, marked the end of the conservative order that had dominated Austria since the Congress of Vienna. These uprisings called for constitutional reforms, national independence, and greater political freedoms, directly challenging the repressive policies that had shaped the Biedermeier period. With the fall of Prince Klemens von Metternich in 1848, Austria underwent significant changes, leading to shifts in artistic and cultural expression. The era of sentimentality and restrained domesticity gave way to more politically engaged and dramatic artistic movements.

As the political climate shifted, so did artistic tastes. The rise of Realism and Historicism in the mid-19th century led many to view Biedermeier art as overly sentimental and conservative. Realist painters such as Gustave Courbet in France and later artists in Austria sought to depict the struggles of working-class life and industrialization, moving away from the quiet domesticity of Biedermeier scenes. Historicism, which celebrated grand narratives and national identity, also pushed Biedermeier art into the background, as audiences became more interested in large-scale historical and mythological themes.

For much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Biedermeier was largely overlooked or dismissed as a minor artistic movement. Critics often viewed it as too nostalgic, lacking the depth or complexity of other styles that had emerged in the same period. However, by the early 20th century, collectors and historians began to reassess its significance, recognizing the craftsmanship and emotional depth present in its works. Art historians started to see Biedermeier as a crucial bridge between Neoclassicism and Realism, with its focus on everyday life foreshadowing later artistic developments.

The revival of interest in Biedermeier was particularly strong in the 20th century, as museums and collectors sought to preserve and exhibit its distinctive style. The elegance and simplicity of Biedermeier furniture, in particular, found new appreciation, influencing the development of modern interior design. By the mid-20th century, Scandinavian and Bauhaus designers drew inspiration from Biedermeier’s clean lines and functional beauty, further cementing its place in design history. Today, Biedermeier art and design are widely valued, with original pieces commanding high prices at auctions and being displayed in major European museums.

The Legacy of Biedermeier in Modern Art and Design

Despite its initial decline, Biedermeier has had a lasting influence on both art and design, shaping aesthetics that continue to resonate in the modern world. One of its most significant contributions was its emphasis on simplicity and realism, which later influenced movements such as Realism and Impressionism. The focus on capturing everyday life with precision and warmth was carried forward by artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and later by Impressionists like Edgar Degas, who sought to depict ordinary people in natural settings. The quiet introspection found in Biedermeier paintings can also be seen in the works of later portrait artists who emphasized character and personality over grandeur.

Biedermeier’s impact extended beyond painting and into decorative arts, particularly in furniture and interior design. The clean lines, functional elegance, and fine craftsmanship of Biedermeier furniture inspired later design movements, including Art Nouveau and the minimalist trends of the 20th century. The Bauhaus movement, which emerged in Germany in the early 20th century, borrowed heavily from Biedermeier’s principles of combining beauty with practicality. Scandinavian design, known for its emphasis on simplicity and craftsmanship, also owes much to Biedermeier’s restrained yet refined aesthetic.

In addition to influencing later artistic and design movements, Biedermeier has maintained a strong presence in museums, auctions, and private collections. Original Biedermeier paintings and furniture remain highly sought after, with collectors appreciating their elegance, craftsmanship, and historical significance. Exhibitions dedicated to Biedermeier art continue to be held in Vienna, Munich, and other European cultural centers, ensuring that the movement remains recognized as a vital part of 19th-century art history. The survival of Biedermeier furniture in both antique and reproduction markets also speaks to its enduring appeal in home decor.

Beyond its stylistic influence, Biedermeier represents an important cultural shift in European art. It was one of the first movements to fully embrace middle-class life as a worthy subject for artistic expression, moving away from the aristocratic and religious themes that had dominated earlier periods. This shift paved the way for the later democratization of art, making it more accessible to everyday people. While often seen as a modest and reserved movement, Biedermeier played a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of European aesthetics, leaving an understated but powerful legacy.

Key Takeaways

- The Biedermeier movement emerged in Austria and Central Europe between 1815 and 1848, emphasizing sentimentality, realism, and domestic life.

- Strict political censorship under the Austrian Empire led artists to focus on intimate, apolitical themes rather than grand historical narratives.

- Key painters such as Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Friedrich von Amerling, and Peter Fendi depicted quiet family scenes, portraits, and natural landscapes.

- Biedermeier extended beyond painting to influence furniture, interior design, and decorative arts, favoring simplicity, elegance, and fine craftsmanship.

- The movement’s legacy continues today, influencing Realism, Scandinavian design, and modern minimalist aesthetics.

FAQs

1. What are the main characteristics of Biedermeier art?

Biedermeier art is known for its realism, sentimental themes, and focus on middle-class domestic life. It features carefully controlled lighting, muted colors, and detailed depictions of interiors, portraits, and landscapes.

2. Why did Biedermeier art avoid political themes?

The Austrian Empire, under Prince Metternich, imposed strict censorship laws that discouraged political expression in art. This led artists to focus on family life, nature, and quiet moments rather than historical or revolutionary subjects.

3. How did Biedermeier furniture differ from earlier European styles?

Biedermeier furniture emphasized functionality, simplicity, and clean lines, in contrast to the ornate designs of the Baroque and Rococo periods. It was designed for comfort and practicality while maintaining aesthetic refinement.

4. What led to the decline of the Biedermeier movement?

The Revolutions of 1848 brought political and social change, shifting artistic tastes toward more expressive and dramatic styles. Realism and Historicism replaced Biedermeier’s intimate and sentimental approach.

5. How is Biedermeier relevant today?

Biedermeier’s principles of elegance, simplicity, and craftsmanship have influenced modern design movements, including Scandinavian minimalism and Bauhaus aesthetics. Its art and furniture remain highly valued in museums and private collections.