Long before European settlers planted fence posts along the Connecticut River or painted its banks in oil, Vermont’s valleys, lakeshores, and mountains held visual significance for the region’s Indigenous peoples—particularly the Western Abenaki, whose ancestral homelands encompass present-day Vermont, New Hampshire, and southern Quebec. These landscapes were not just geographic markers but symbolic fields, alive with memory, narrative, and spiritual presence. Their visual culture was largely ephemeral or integrated into daily life, which complicates the modern appetite for static, collectible “art” objects. Still, traces remain—not in canvases or framed artifacts, but in carvings, patterns, and sacred sites embedded in the land itself.

Among the most enduring examples are petroglyphs along the western shore of Lake Champlain, particularly near the mouth of the Otter Creek. These rock engravings, attributed to Abenaki artists centuries before European arrival, depict stylized human figures, animals, and abstract forms. Their precise meaning is debated. Some interpretations suggest they record mythic events; others propose a cosmological map or a ritual marker. Like much of early Indigenous art in the Northeast, these images resist the boundaries of art history as conventionally practiced: they are not dated in neat chronological order, not signed, and not designed for gallery walls. They are part of a cosmology in which artistic practice, storytelling, and survival are inseparable.

Three types of Indigenous visual expression in precolonial Vermont remain especially important for understanding this deeper visual language:

- Wampum belts used not only in diplomacy but as mnemonic devices to record agreements and stories, with intricate beadwork often carrying symbolic color patterns.

- Bark etchings and incised birchbark scrolls, common in Algonquian-speaking cultures, sometimes used to pass on medicinal, spiritual, or territorial knowledge.

- Seasonal markings and trail signs carved into trees or rocks, acting as spatial guides and ritual indicators, many of which have vanished or been overgrown.

Much of this material was portable, organic, and therefore perishable—a fact that both frustrates modern historians and serves as a reminder that artistic permanence was never the point. The land, constantly moving, freezing, thawing, and breathing, was the primary canvas.

The silence of the museum

Walk into a Vermont museum today—any mid-sized historical society, a campus gallery, even the state’s flagship art institution—and you’ll likely notice a telling absence: the near-total erasure of pre-contact Indigenous visual culture. This is not due to a lack of artistic production, but to a combination of erasure, collecting bias, and institutional neglect. When early European settlers and antiquarians in the 18th and 19th centuries began recording the visual culture of New England, their interest lay primarily in documenting the so-called vanishing Indian or in appropriating symbols that reinforced their own narrative of conquest and settlement.

The story of the petroglyphs themselves illustrates this dynamic. First documented by European settlers in the early 1700s, they were long treated as curiosities or natural oddities rather than serious cultural artifacts. In several cases, petroglyphs were chiseled out and relocated to private collections or “preserved” by being sealed off from the landscape that gave them meaning. As museums across Vermont began to formalize in the 20th century, few made efforts to interpret or exhibit Indigenous art on its own terms. Instead, when Indigenous objects were displayed, they were often detached from their cultural function—reduced to typologies of arrowheads or beadwork, used to narrate settler history rather than Indigenous presence.

The structural silence around Abenaki visual culture deepened during the 20th century, when the State of Vermont denied the very existence of living Abenaki communities for nearly a hundred years. This political erasure had cultural consequences. Without recognition, there was little public support for Indigenous-led institutions, repatriation efforts, or cultural preservation. Visual traditions were preserved in private, often passed down informally within families or revitalized through intertribal networks in the broader Northeast.

But the museum silence is not just a local failure—it reflects a broader aesthetic bias. Much of what constitutes Indigenous artistic expression in this region does not fit neatly into European-derived categories of “fine art.” It is wearable, functional, seasonal, and community-based. It speaks in rhythm with nature, not against it. And because it is deeply tied to oral tradition and place-based ritual, it resists the static, decontextualized mode of display favored by most art institutions.

Reclaiming Abenaki visibility

The past two decades have seen a slow, uneven shift. Abenaki artists, activists, and educators have worked to reclaim both legal recognition and cultural visibility—efforts that include a visual component, even if it rarely takes center stage. Artists like Jeanne Morningstar Kent and Melody Walker Brook have woven traditional patterns into contemporary beadwork, regalia, and pedagogical materials. Others have experimented with mixed media, combining quillwork or ash splint basketry with modern design, deliberately collapsing the imagined boundary between the historical and the contemporary.

One of the most quietly powerful scenes in Vermont’s recent art history occurred not in a gallery but along a riverbank: a 21st-century ceremony to honor the ancient petroglyphs near Brattleboro, during which Abenaki elders and young artists re-inscribed the visual significance of those rocks—not by carving, but by dancing, singing, and offering. This act of reverence reasserted the site’s cultural power without altering the stone. It was a reminder that visual art, in the Indigenous tradition, does not always mean object-making. It means making meaning visible.

More formal institutional changes have followed, albeit haltingly. The Vermont Folklife Center, the Abenaki Arts and Education Center, and several small museums have begun to collaborate with Indigenous artists and elders on more accurate and participatory exhibits. Yet these efforts remain underfunded and largely peripheral to the mainstream Vermont art scene, which still tends to define its roots through a white, pastoral lineage—starting with the Hudson River School or the artists’ colonies of the 20th century.

Rebuilding a fuller art history of Vermont requires expanding the frame. It requires understanding that the land was not a blank canvas awaiting the brushstrokes of white settlers, but a densely marked and symbolically rich place long before Europeans arrived. And it requires confronting the fact that the foundations of Vermont’s artistic self-image—its natural beauty, rustic charm, and independent spirit—rest in part on what was obscured, buried, or ignored.

The stone still speaks, if you know how to look. But much of its message must now be reassembled—not from preserved artifacts, but from fractured memory, living practice, and acts of cultural re-inscription that are as political as they are aesthetic.

Chapter 2: Picturesque Authority: 18th-Century Surveyors and the Invention of the Vermont View

Mapping as ideology

Vermont’s art history begins in earnest not with easels and studios, but with compasses, chains, and surveyor’s sketchbooks. In the mid-to-late 1700s, the land that would become Vermont was still a contested territory—claimed simultaneously by New York and New Hampshire, sparsely inhabited by settlers, and home to a dwindling number of Indigenous families. Into this uncertainty came the mapmakers: men hired to delineate boundaries, parcel out land, and make the unknown legible. Their drawings were not simply technical records—they were among the first visualizations of the region as a place to be possessed, cultivated, and eventually aestheticized.

The early surveys of Vermont tell us more than just property lines. They encode a settler vision of the land as ordered, productive, and picturesque—qualities that would come to define the state’s cultural identity in the centuries ahead. Take, for example, the work of Ira Allen, brother of Ethan Allen and chief architect of Vermont’s early cartographic infrastructure. His 1798 map of the state, hand-colored and obsessively detailed, presents the Green Mountains not as a forbidding barrier but as a central spine—something to be traversed and admired. Rivers are gracefully winding, towns neatly gridded, and forests reduced to generic symbols. The wilderness is not so wild anymore.

But beneath the surface of such cartography lies a quieter visual ideology. These maps turned complex, lived landscapes into abstracted, ownable plots. They replaced Indigenous place names with English ones. They rendered forests into timber reserves, mountains into elevations to be admired, and rivers into future power sources. In short, they were aesthetic weapons as much as administrative tools. Every line drawn by a surveyor reinforced the notion that this land had become a canvas for New England civility, awaiting the careful brush of the colonial settler.

This aesthetic logic seeped into early visual representations of Vermont in more explicitly artistic forms as well. Watercolor views of townships, commissioned by wealthy landowners or local governments, often depicted villages nestled snugly between hills, framed by fields and tidy fences. These works borrowed from the compositional strategies of English landscape painting—balanced symmetry, framed views, harmonious human-nature integration—but repurposed them for the American context. The goal was not contemplation, but affirmation. These were not romantic wildernesses to get lost in. They were landscapes that said: we are here now, and this is ours.

Early renderings of “wilderness”

There is an ironic absence at the center of early Vermont art: the wilderness itself. Though 18th-century writers and travelers often described the region in terms of its “sublime” beauty or “unbroken” forests, visual artists rarely depicted this raw nature directly. Instead, we get controlled fragments: a mountain in the background, a stand of trees along a road, a distant forest tamed by a cleared field. The untamed landscape remained largely invisible—not because it was unseen, but because it was culturally inconvenient. To depict it fully might acknowledge its danger, its otherness, or its prior inhabitants.

A revealing example comes from a 1780s engraving published in The Massachusetts Magazine, showing a generic Vermont valley dotted with a few stumps, scattered cabins, and a church steeple rising optimistically into the sky. The proportions are off—the mountains too low, the sky too calm—but the message is clear. Nature has been made usable. The wilderness has yielded. It is not the awe-striking chaos of the Alps, but the manageable beauty of a country ready for moral cultivation.

And yet, traces of ambivalence linger. In some sketches and engravings from this period, especially those by itinerant artists who passed through Vermont on their way to more populous centers, the mountains loom awkwardly in the background—neither fully integrated nor completely ignored. They are like uninvited guests in a group portrait: visible, but not acknowledged. These early images capture a moment before Vermont’s landscape was fully aestheticized, when the land still retained an edge of unpredictability. It was, quite literally, still forming—geologically, politically, and visually.

This tentative relationship to the land echoes broader themes in American visual culture during the Revolutionary era. In the words of art historian Angela Miller, the early national period was characterized by an “aesthetic of control”—a desire to shape not only land, but history itself, into legible, virtuous narratives. Vermont, newly independent (and for a brief time its own republic), was no exception. Its early images were attempts to assert a visual order onto a space that remained deeply unsettled.

Settler aesthetics and property

By the turn of the 19th century, the settler vision of Vermont had taken firmer root—not just politically, but visually. Land ownership was no longer merely practical; it had become aesthetic. To own land was to frame it, shape it, and display it as part of one’s moral and economic standing. In this context, the notion of the “view”—as in, a view from the front porch, a view from the hilltop—took on special importance. What had once been surveyed as territory was now rendered as scenery.

This transformation can be seen in the proliferation of small amateur landscapes produced by Vermont’s early elite: farmers, lawyers, ministers, and merchants who dabbled in watercolor or drawing. Many of these works are anonymous, their creators lost to history. But their subjects are revealing. Time and again, we see the same compositional logic: a central house or farm, flanked by cultivated fields, with a river or mountain tastefully visible in the distance. These were not imaginative landscapes. They were property statements. They made the claim, both literal and symbolic, that Vermont had been made visible, and therefore made safe.

Three visual conventions emerge repeatedly in these works:

- Fences or stone walls framing the foreground, emphasizing control and demarcation.

- A central human structure, often a homestead, mill, or church, as the stabilizing visual anchor.

- Distant hills or woods, depicted in softened tones to suggest harmony rather than threat.

Together, these compositional habits helped fix the visual identity of Vermont as a place where nature and culture coexisted peacefully—an idea that would be exported in the 19th century by more accomplished artists, and eventually codified in tourism literature, guidebooks, and regional branding. But in its earliest form, this visual identity served a more intimate function: it reassured the settler of his rightful place.

The irony is that this vision was achieved through omission. The wilderness was present, but downplayed. The Indigenous past was erased. The labor of clearing and farming—often brutal, backbreaking, and dangerous—was rendered invisible. What remained was the view. Not what the land had been, or what it demanded, but what it could be seen to represent: peace, order, virtue.

This was not simply a matter of style. It was a form of visual governance. The early art of Vermont, in its surveys, engravings, and drawings, did not reflect the land so much as it instructed viewers how to see it. It told them that this was a land worth owning, taming, and admiring. And in doing so, it laid the groundwork for the Vermont that would later be painted, photographed, and idealized—not as a frontier, but as a viewscape.

Chapter 3: Green Mountains Sublime: The Landscape Painters of the 19th Century

Thomas Cole’s pass through the Champlain Valley

In 1837, the Anglo-American painter Thomas Cole—the founding figure of the Hudson River School—traveled briefly through Vermont’s Champlain Valley on his way to Montreal. He left behind only fragmentary notes about the state, describing it as “agreeably rural” and “less wild than expected,” yet the echoes of his aesthetic philosophy would eventually resound through Vermont’s hills and river valleys for decades. Even without extensive firsthand engagement, Cole’s influence helped cast the Green Mountains into the visual mythology of the American sublime: a blend of rugged natural beauty, moral purity, and romantic solitude.

The Hudson River School, despite its name, was never confined to the Hudson Valley. It represented a broader nationalist movement in American painting during the mid-19th century, in which artists sought to define the young republic’s identity through landscape. The untamed vistas of the Northeast, and later the West, offered painters a subject that was both aesthetically rich and ideologically potent. Within this framework, Vermont became a kind of proving ground: less dramatic than the White Mountains, more cultivated than the Adirondacks, and full of what one critic called “elevated rusticity”—a place where the pastoral and the sublime overlapped.

By the 1840s and ’50s, itinerant artists and serious painters alike began making regular forays into the Vermont countryside, sketching from high ridges, composing studio canvases from field drawings, and exhibiting their work in Boston and New York. The art they produced walked a fine line between romantic grandeur and sentimental domesticity—a balance uniquely suited to Vermont’s topography. The mountains were steep, but not overwhelming. The valleys were wide and luminous. And the land, increasingly settled but still visibly rough, offered just enough texture to suggest authenticity without danger.

One of the most notable painters to engage with Vermont directly during this period was Asher B. Durand, Cole’s friend and successor. Durand’s painting The Beeches (1845), though not set in Vermont, captures the type of scenery—mixed hardwood forests, filtered mountain light, quiet woodland interiors—that characterized much of the state’s terrain. His occasional Vermont sketches, now held in private collections and museums, suggest a reverence for the state’s quieter moods: mist on lake water, the slope of a field at dusk, a stone bridge crossing a stream. For Durand and his contemporaries, Vermont was not only paintable—it was morally upright, an antidote to the corruption of the city.

The pastoral frontier

As the century progressed, Vermont’s visual identity came to inhabit a kind of middle register. It was neither savage nor wholly civilized. Instead, it represented a pastoral frontier—where the marks of human labor were visible but not obtrusive, and where nature retained its authority even as it was gently shaped. This balance made it an ideal subject for the growing number of regional painters who sought to contribute to American landscape painting without entering the competitive, cosmopolitan worlds of New York or Philadelphia.

Among them was Charles Louis Heyde, a now little-known but once prolific Vermont-based painter who settled in Burlington in the 1850s and made the Green Mountains his primary subject for nearly four decades. Heyde’s paintings, though uneven in execution, are significant for their local specificity. He painted Otter Creek, Camel’s Hump, and Mount Mansfield with obsessive attention, returning to the same views across different seasons and times of day. His palette often veered toward the theatrical—sunsets lit like stage scenes, autumn trees in burning red—but beneath the spectacle lay a genuine attempt to translate the Vermont landscape into a painterly vocabulary.

Heyde was also among the first artists to exhibit Vermont landscapes under explicitly regional titles—View of Middlebury from the Hill, Twilight on Lake Champlain, Autumn near Barre—which helped establish the state as a distinct aesthetic zone. His work, sold through East Coast galleries and local patrons, circulated Vermont’s image to a growing audience of middle-class viewers who saw in these scenes both familiarity and aspiration.

This version of Vermont—the cleared pasture with its lone cow, the white steeple village nestled beneath mountain peaks, the dirt road winding through birch and beech—became a staple of regional painting. It was not merely decorative. It functioned as a cultural reassurance: a vision of American life that was orderly, humble, and in harmony with nature. In a period marked by industrial expansion, immigration anxiety, and political unrest, Vermont’s painted views offered a counter-image of stability. Whether or not this vision aligned with reality was beside the point. It satisfied a visual hunger for permanence.

Local painters and the Hudson River School’s long shadow

Though most of the major Hudson River School painters touched Vermont only lightly—if at all—their influence lingered across the century in the work of local and regional artists who adapted the style to smaller ambitions. These painters, often self-taught or trained at minor academies, produced work that sat somewhere between fine art and folk practice. Their canvases filled parlor walls, town halls, and local exhibitions. They rarely made it into national collections, but they shaped how Vermonters saw their own landscape.

Painters such as James Hope, who lived for many years in Castleton, and Albert Bierstadt’s lesser-known brother Charles Bierstadt, who worked as a photographer and painter in Brattleboro, left behind bodies of work that blended precise local topography with romantic idealization. Their depictions of waterfalls, mills, and mountain passes were not only records—they were propositions. They asked viewers to believe in a Vermont that was noble, unspoiled, and spiritually charged.

What distinguishes much of this work from the canonical Hudson River School is its emotional register. Where Thomas Cole often used landscape to meditate on mortality and empire, Vermont painters were more concerned with continuity and endurance. Their mountains did not crumble with the passage of time—they held steady. Their forests were not vanishing—they were sheltering. In these choices lies a subtle regional ethos: one of modest grandeur, quiet dignity, and moral clarity.

Three recurrent themes emerge in Vermont’s 19th-century landscape painting:

- The prominence of light filtering through trees, suggesting divine immanence rather than dramatic revelation.

- Carefully balanced compositions, with human structures small but central—signs of belonging rather than dominance.

- A restrained emotional tone, avoiding extremes of fear or awe in favor of contemplation and gratitude.

This sensibility helped insulate Vermont painting from some of the more theatrical excesses that overtook American art later in the century. Even as artists elsewhere chased grandeur, exoticism, or allegory, Vermont’s visual tradition remained rooted in its own soil—sometimes to a fault. The result was a body of work that, while often overlooked by critics, built a durable local visual language. Its motifs—stone fences, sugar maples, still ponds, and soft mountains—became so familiar they now border on cliché. But they began as revelations.

By the century’s end, Vermont had become not only a state, but a state of mind—fixed in the public imagination as a place where nature was not threatening, but reassuring; not sublime in the European sense, but quietly transcendent. And this image, constructed in paint and paper, would shape not just how others saw Vermont, but how Vermonters came to see themselves.

Chapter 4: Folk Forms and Frugal Brushes: Rural Portraiture and the Decorative Arts

Tin painters and traveling limners

In the parlors of 19th-century Vermont farmhouses, above cast-iron stoves and beside tall-case clocks, hung portraits whose makers’ names are now mostly lost. The faces in these paintings are direct and plain, their expressions fixed in stoic reserve or soft apprehension. These were not the works of academy-trained artists chasing fame in Boston or New York. They were painted by limners—traveling artists of varying skill who moved from town to town offering likenesses to those who could afford neither time nor money for more refined commissions.

These portraits occupy a distinct place in Vermont’s visual culture. They are not grand in scale or ambition, but they are intimate, and often arresting. Painted on tin, wood panel, or repurposed canvas, they were produced with limited palettes and makeshift tools. The paint is frequently thin; the brushwork utilitarian. Yet within these constraints, something essential was captured—an assertion of identity, permanence, and respectability in a world where life was fragile and death was never far away.

Most Vermont limners worked anonymously, signing few if any of their pieces. Some came from neighboring states—New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York—and made seasonal circuits through the Green Mountains. A few left fuller records, such as Joseph H. Davis, who painted dozens of watercolor portraits in the 1830s in the Upper Connecticut River Valley, and Ruth Henshaw Bascom, whose pastel portraits from southern Vermont and Massachusetts preserve some of the only known images of rural women and children from that period.

These painters rarely captured heroic poses or dynamic gestures. Instead, they focused on the small social signals that mattered to their sitters: a book held in hand to suggest literacy, a modest brooch or ribbon as a symbol of refinement, a patterned carpet or drapery rendered with stiff formality. The faces are often disproportionately large, the eyes wide and a little too bright—an effect that can feel eerie today but was meant to convey clarity and moral presence.

This genre of portraiture was not unique to Vermont, but it took on a particular resonance here. In a state with no major metropolitan center, limited wealth, and strong traditions of independence and modesty, the folk portrait functioned less as a status symbol and more as a declaration of existence. These portraits were not commissioned to impress visitors; they were meant to be kept, remembered, and passed down. Their very awkwardness—their refusal of polish—is part of their power.

Quilts, cupboards, and fraktur

Beyond portraiture, a rich tradition of decorative and utilitarian arts flourished in 19th-century Vermont, though it rarely entered galleries or museums during its own time. These forms—quilts, painted furniture, calligraphic drawings, and other domestic crafts—were made primarily by women, immigrants, and artisans working far from cultural centers. Their work was often unsigned, unexhibited, and undervalued, despite its technical intricacy and visual sophistication.

One of the most vibrant of these traditions was quilting. Vermont quilts from the mid-1800s are notable for their inventive patterns, vibrant colors, and precise needlework. They range from simple whole-cloth bedcovers in deep indigo or madder brown to elaborately pieced and appliquéd works that took months, sometimes years, to complete. These quilts were not just functional—they were aesthetic statements. Their motifs often carried symbolic meaning: stars for guidance, trees for rootedness, interlocking rings for marriage. In some cases, they incorporated scraps of family clothing, turning the quilt into a tactile archive of memory and loss.

Cabinetmaking also flourished in 19th-century Vermont, especially in Windsor and Rutland counties. Painted chests, cupboards, and blanket boxes decorated with stylized vines, birds, or geometric bands reveal a blend of New England restraint and Germanic folk influence. The influence of immigrant craftsmen—particularly German, Swiss, and French Canadians—is evident in the visual language of these objects, which often combined functional clarity with bursts of ornamental bravado. A simple pine cupboard might feature trompe-l’œil panels, faux grain painting, or hand-carved rosettes—details that elevated the object from utility to statement.

Among the most visually striking artifacts of the period are pieces of fraktur—illuminated calligraphy and folk drawing produced by German-speaking settlers in southern Vermont. Often made to commemorate births, marriages, or baptisms, these documents feature dense script surrounded by hearts, birds, tulips, and sunbursts in watercolor and ink. While more commonly associated with Pennsylvania Dutch communities, fraktur found a foothold in parts of Vermont as settlers migrated north. These works, too, were rarely framed or exhibited. They were folded, stored, or pasted into family Bibles—kept close, rather than displayed.

Three features characterize Vermont’s 19th-century decorative arts:

- Intimate scale: Most objects were made for domestic use and private display, rather than public admiration.

- Hybrid visual vocabularies: Designs blended regional traditions with imported motifs, reflecting the mixed cultural heritage of Vermont’s settlers.

- Material pragmatism: Makers used what was available—pine, tin, wool, local dyes—and transformed it through labor and invention into objects of lasting beauty.

The result is a visual archive that, though scattered and often fragile, offers profound insight into the everyday aesthetics of rural life—where beauty was made, not bought, and where art lived in use rather than in theory.

Everyday beauty and anonymity

There is a tendency in traditional art history to focus on named creators, documented works, and institutional validation. But the visual legacy of 19th-century Vermont resists such framing. Much of its art was made anonymously, passed hand to hand, or created for specific, fleeting occasions—such as a death, a wedding, or the turning of a season. These works ask to be seen not as isolated masterpieces, but as expressions of a larger visual ethos: one in which art was embedded in life, not set apart from it.

This ethos is evident in diaries and letters from the period. One mid-century Vermont woman wrote of sewing a quilt “for when the baby comes, to busy the hands while the heart worries.” A cabinetmaker’s ledger from 1843 includes notations about hand-painted details added “for the Misses L.” without charging extra—suggesting not only skill, but pride. These makers rarely spoke of themselves as artists, yet they created forms of lasting aesthetic significance. Their works were not timeless in the grand sense. But they endured in other ways: through wear, repair, and memory.

It was not until the early 20th century, with the rise of American folk art collecting, that many of these objects were reconsidered as art at all. Figures like Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Edith Gregor Halpert began to collect and promote rural portraiture, quilts, and painted furniture as authentically “American” in spirit—simple, direct, and unschooled. Museums followed suit. Suddenly, Vermont’s humble artifacts became desirable, though often stripped of their original context. A painted chest that once sat in a barn loft might now reside behind glass in a New York institution, its maker anonymous but its price tag considerable.

This reclassification was both recognition and loss. It elevated the craftsmanship of Vermont’s rural past but often severed it from the lives and values that had shaped it. Still, something persists in the work itself: a kind of moral clarity, born not of dogma but of attention. These were objects made carefully, with respect for the materials and for the rhythms of domestic life. They remind us that beauty need not be grand or public to matter deeply.

And they complicate the usual trajectory of art history. In Vermont, some of the most resonant visual works were not painted in oils or exhibited in salons. They were sewn, carved, lettered, and worn. They hung in kitchens and were wrapped around bodies. They were buried, burned, passed down, or forgotten. Yet they remain—in museums, in attics, in the gaze of descendants who still see their ancestors’ hands in every stitched star or carved leaf.

Chapter 5: Town Greens and Marble Gods: Civic Sculpture and Memory in the Gilded Age

Civil War monuments and moral certainty

In the late 19th century, the village green—a civic fixture in nearly every Vermont town—became the preferred pedestal for a new kind of art: public sculpture. Though the state’s earlier artistic expressions had been intimate and domestic, the Gilded Age ushered in a more monumental impulse, driven by wealth, nationalism, and a desire to fix historical memory in stone. The most common—and telling—of these sculptures were Civil War memorials: upright, solemn, usually in granite, often depicting a lone soldier at rest with musket in hand.

Between 1865 and 1915, more than 100 Civil War monuments were erected across Vermont, a state that had contributed more than 34,000 troops to the Union cause. These monuments were not merely commemorative; they were aspirational. They aimed to present a coherent narrative of sacrifice, unity, and moral triumph, even as the social and political realities of post-war America grew more fragmented. In many towns, the war monument became the visual and symbolic center of civic identity—a literal and figurative elevation of values deemed essential: bravery, loyalty, and stoic endurance.

The sculptural style was typically conservative. The “soldier at parade rest” type—repeated in Barre, Middlebury, Montpelier, and dozens of smaller villages—was preferred over more dynamic or interpretive forms. This sameness was intentional. It emphasized collective memory over individual experience. It also allowed small towns to participate in a national visual language without the cost or risk of artistic innovation. Most of these monuments were commissioned from regional stone carvers or ordered from catalogues. The aesthetic was one of clarity, legibility, and permanence.

But even within these constraints, variations emerge. Some statues are striking in their scale, rising on columns thirty or forty feet high. Others incorporate bronze plaques, carved bas-reliefs, or allegorical figures such as Victory or Liberty. In Bennington, a more ambitious vision took shape: the massive Bennington Battle Monument, completed in 1889, which commemorates a Revolutionary War victory but was designed in part to echo Civil War ideals. Its stark obelisk form—tall, impersonal, unyielding—symbolizes both remembrance and conquest.

For many Vermonters, these sculptures served a dual function. They memorialized the dead and asserted a moral framework for the living. In a rapidly industrializing America, with rising immigration and political upheaval, the Civil War monument on the green offered reassurance that the past was settled, and its lessons clear.

Barre granite and immigrant labor

The rise of public sculpture in Vermont during the Gilded Age was not just a story of patronage and patriotism—it was also a story of labor. Nowhere is this more evident than in Barre, a small city in central Vermont that became, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, one of the nation’s leading centers of granite quarrying and carving. The high-quality gray granite found in Barre was prized for its fine grain and durability, making it ideal for both architectural and sculptural use.

By 1890, Barre’s granite industry employed hundreds of workers, many of them immigrants from Italy, Scotland, Spain, and Scandinavia. These craftsmen brought with them long traditions of stone carving and quickly transformed the town into a hub of artisanal production. Walking through Barre’s Hope Cemetery today, one encounters not just somber memorials, but exuberant declarations of skill and personality: lifelike busts, carved racecars, granite pillows, open books, and even a replica of a soccer ball—all rendered in unforgiving stone.

These monuments, though often funerary in purpose, blur the line between public and private art. They are personal commissions, but many display a technical and expressive ambition that rivals gallery sculpture. Some serve as direct homages to the craft itself—depicting chisels, hammers, and other tools. Others function as political or philosophical statements. The Italian stone workers, many of whom were socialists or anarchists, occasionally carved inscriptions that challenged religious orthodoxy or emphasized labor solidarity.

One such artisan was Elia Corti, an Italian carver whose dramatic tomb features a broken column—symbolizing a life cut short—and a striking portrait medallion. Corti’s life and death (he was shot in a labor dispute in 1903) encapsulate the tensions of the era: between capital and labor, tradition and modernity, monument and mortality. Barre’s cemeteries, in this light, become more than burial grounds. They are open-air galleries, saturated with the history of immigrant resilience and artistic defiance.

Three defining characteristics mark this sculptural culture:

- Technical virtuosity, often achieved under difficult and dangerous working conditions.

- Hybrid symbolism, combining European iconography with local themes and materials.

- Democratic visibility, as the cemetery became a public space for both mourning and admiration.

While much of Vermont’s earlier visual culture emphasized modesty, the granite art of Barre exudes a different ethos: pride in craft, assertion of identity, and resistance to invisibility. It is among the state’s most vivid artistic legacies, carved into stone by those who seldom appeared in the portraits or paintings of their time.

Victorian beautification campaigns

The Gilded Age was not only about memory—it was also about image. As towns grew wealthier and more self-conscious, they invested in civic beautification projects that blurred the line between utility and ornament. Public fountains, bandstands, iron fences, and ornamental plantings began to populate Vermont’s greens and promenades. Though modest by urban standards, these additions reflected a national movement influenced by the City Beautiful ideals emerging in places like Chicago and Washington, D.C.

In Vermont, this translated into a localized aesthetic of order, cleanliness, and visual symmetry. Town planners and civic boosters, often aligned with women’s clubs or improvement societies, advocated for paved walkways, gaslights, decorative urns, and neatly trimmed hedges. Public art, in this context, served a socializing function—it encouraged respectability, discouraged vagrancy, and presented the town as morally upright and culturally ambitious.

One of the most common expressions of this effort was the installation of commemorative fountains. These were often dedicated to temperance advocates, civic benefactors, or even beloved animals. In Montpelier, a granite horse trough carved with classical scrollwork doubled as a drinking fountain and a civic emblem. In smaller towns like St. Johnsbury or Bellows Falls, fountains became focal points of the green—a blend of utility and ornamentation that reflected the Victorian ideal of moralized design.

These beautification efforts often intersected with the period’s artistic production. Local carvers and metalworkers were hired to create railings, plaques, or finials; schoolchildren were brought to “art appreciation” picnics around new installations. The art may have been modest, but the impulse was clear: to transform the town into a visual expression of its civic virtues.

It was also, in part, a response to anxiety. The rise of industry, the influx of immigrants, and the growing distance between rural life and urban modernity led many Vermonters to cling more tightly to visual order. Public sculpture and decoration became not just aesthetic enhancements, but cultural defenses—against disorder, against forgetting, against change.

Even today, one can walk across a Vermont town green and read, in the spacing of trees and the placement of statues, the values of a prior age. These spaces are not neutral. They are curated environments, designed to produce emotion and allegiance. And while the art may appear static—unmoving soldiers, unchanging stone—the meanings shift with each generation that passes by.

Chapter 6: Summer Colonies and Studio Barns: Vermont as Artist’s Refuge, 1890–1940

The rise of the art colony at Woodstock

By the final decade of the 19th century, Vermont’s aesthetic identity had been largely shaped in the public imagination: a place of pastoral serenity, moral clarity, and picturesque endurance. But for a growing number of artists, particularly those weary of urban art markets or seeking fresh inspiration outside established centers, Vermont offered something more intimate and creatively liberating. Beginning in the 1890s, scattered clusters of painters, printmakers, and illustrators began to establish seasonal residencies in the state—often renting or purchasing old farms and barns, where they could live cheaply and work uninterrupted.

The town of Woodstock, already popular among affluent summer tourists, became one of the first informal art colonies in Vermont. Drawn by the area’s luminous valleys and access to the Ottauquechee River, artists established a quiet but sustained presence there. Charles H. Woodbury, a prominent marine painter based in Ogunquit, Maine, taught summer sketching classes in the region in the 1910s. Henry C. White, a lesser-known but prolific tonalist, produced dozens of moody, atmospheric Vermont landscapes during his stays near Woodstock. Their presence attracted students and fellow artists, many of whom stayed on or returned annually.

Unlike more organized colonies such as the one in Cornish, New Hampshire, Woodstock’s artistic community remained informal and scattered, more of a social pattern than a branded movement. But the effect was notable. Over time, a distinct visual vocabulary emerged among these summer artists: one rooted less in grandeur than in tonal subtlety. Their works often depicted Vermont not in the brilliant color of autumn or the dramatic contrast of mountain ranges, but in the haze of humid midsummer mornings or the pale quiet of early spring thaws.

For these artists, Vermont was not merely a backdrop. It was a psychological refuge—a place where time moved differently, and the rules of the coastal art world did not apply. They came not just to paint the landscape, but to enter into it. The barns they worked in became studios; the towns they visited became rhythms. There was, in many cases, a retreat from irony, from competition, and from spectacle.

This turn inward, toward a quieter kind of expression, would define much of the art made in Vermont over the next half-century. It also helped reinforce an enduring pattern: that of Vermont as a place to withdraw from the mainstream in order to make something more sincere.

Women artists in rural exile

For many women artists, Vermont offered more than quiet—it offered freedom. In an era when opportunities for serious artistic development were still limited for women, and when domestic expectations often strangled creative ambition, Vermont’s remoteness could be a kind of permission. Several female painters and illustrators made the state their part-time or permanent home during the early 20th century, using its rural solitude not just as subject matter but as structural support for their practice.

One such figure was Mary Rogers Williams, a Smith College art professor and pastelist whose travels frequently brought her through the Vermont hills. Her letters describe days spent sketching from a wagon, sleeping in barns, and negotiating with farmers for room and board. Though better known for her European work, her Vermont scenes capture something quieter and more personal: woods at dusk, muddy roads, frost on fence rails. These were not views composed for exhibition—they were painted to be remembered.

Even more rooted was Augusta Metcalfe, a lesser-known but prolific painter who lived and worked in central Vermont through the 1920s and ’30s. Metcalfe never sought fame and rarely exhibited outside the region. Her paintings of working farms, sugaring season, and ramshackle sheds reveal a deep familiarity with the rhythms of rural labor. In their looseness and lack of pretension, they reject both romanticism and critique. They are, simply, records of how things looked—and felt—when seen by someone who truly lived among them.

This kind of quiet immersion was also evident in the decorative and craft-based work of women artists who came to Vermont to escape rigid gender expectations. Weavers, potters, and bookbinders found in Vermont’s rural economy both need and respect for handmade goods. The physical demands of farming life gave weight to their labor; the isolation gave space for invention. These were not dilettantes on holiday—they were serious makers, often balancing artistic practice with subsistence.

Three patterns define this early 20th-century influx of women artists into Vermont:

- Seasonal solitude: Many came only in summer or fall, aligning their work with Vermont’s rhythms and returns.

- Amateur-professional overlap: The boundary between domestic craft and fine art was often blurred, by choice and by necessity.

- Intentional obscurity: Rather than pushing for visibility, many chose self-sufficiency, even if it meant marginalization.

Their legacy has often been underrecognized—overshadowed by male regionalists or simply left out of the dominant art historical narratives. But their work helped redefine what it meant to be an artist in Vermont: not just someone who painted the state, but someone who lived its textures, its silences, and its seasons.

The fusion of regionalism and modernism

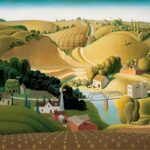

By the 1930s, a curious convergence had taken root in Vermont’s artistic life. On one hand, the state had become a stronghold for American regionalism—a movement that celebrated local subjects, traditional techniques, and rural values. On the other hand, it had quietly begun to absorb aspects of modernist experimentation, brought in by émigré artists, urban exiles, and college educators who found in Vermont a safe ground for risk.

This fusion can be seen in the work of Luigi Lucioni, an Italian-born painter who moved to Manchester, Vermont in the 1930s and became one of the state’s most recognizable artistic figures. Lucioni’s meticulously rendered still lifes and landscapes combine academic precision with modernist framing. His paintings of gnarled trees, peeling barns, and overgrown meadows are neither nostalgic nor abstract. They sit between worlds—realist in detail, yet psychologically charged. Lucioni once described Vermont as “a place where everything is visible, nothing is hidden.” His canvases take that visibility to its furthest extreme.

At the same time, institutions like Middlebury College and Bennington College began to hire artists who brought more cosmopolitan aesthetics into conversation with Vermont’s traditions. The sculptor and printmaker Karl Knaths, associated with early American abstraction, taught in Vermont during the 1930s. His angular, Cubist-inflected compositions of barns and boats offer a radically different Vermont—fractured, stylized, analytical. These were not romantic scenes but visual inquiries.

The cross-pollination between regional loyalty and modernist structure produced a unique moment in Vermont art. It created work that was neither purely local nor fully international; neither nostalgic nor aggressively avant-garde. Instead, it occupied a subtle middle space—where a stone wall could be both literal and metaphoric, where a hayfield could hold formal tension.

This era also birthed the first real recognition of Vermont as a viable long-term home for serious artists. No longer just a summer retreat or creative exile, the state began to attract those who saw in its quiet not withdrawal, but possibility. Artists built their own studios from barns. They taught at small colleges, traded work for supplies, and accepted obscurity in exchange for continuity.

And with this shift came a new kind of Vermont art: rooted, yes, but also restless; grounded in soil, but open to weather.

Chapter 7: Abstract in the Attic: Modernism, Mysticism, and the Vermont Avant-Garde

Wolfgang Paalen, Louis Moyse, and the outsiders

By the mid-20th century, Vermont had become something of a paradox in American art. It remained a rural, peripheral state with limited institutional infrastructure, yet it attracted a surprising array of serious and often radical artists—many of whom found in its isolation not provinciality, but liberation. These arrivals did not belong to any unified movement. They came alone or in pairs, brought by marriage, war, teaching opportunities, or sheer curiosity. What united them was a shared appetite for slowness, for quiet, and for an experimental freedom often harder to find in the urban art scenes of New York or Paris.

Among the most intellectually potent of these figures was Wolfgang Paalen, the Austrian-Mexican surrealist and philosopher who visited Vermont in the 1940s while on a circuitous exile from Europe. Though best known for his work in Mexico and his influence on surrealist theory, Paalen’s Vermont sojourn left a subtle trace: he conducted informal salons in Brattleboro, gave talks at local colleges, and sketched the forests and rivers with a mix of mystical fervor and conceptual precision. While he made little work in Vermont itself, his presence—as a thinker, as an exile, as a provocateur—marked a turning point. The state could now host not just regionalists or recluse painters, but cosmopolitan avant-gardists seeking psychic sanctuary.

Another, more enduring figure was Louis Moyse, the French-born flutist and composer who settled in Brattleboro and co-founded the Marlboro Music Festival. Though not a visual artist, Moyse’s presence shaped the interdisciplinary character of mid-century Vermont art life. Artists, musicians, dancers, and writers mingled in an informal network that blurred disciplinary lines. Painters created stage sets, musicians took up photography, and sculptors worked with choreographers. It was less a movement than a mood—rooted in improvisation and cross-pollination.

This permeability of practice attracted artists whose work resisted classification. The abstract painter Paul Sample, who served as artist-in-residence at Dartmouth College, lived just across the Connecticut River but spent much time in southern Vermont. His paintings, especially those from the 1940s and ’50s, integrate bold modernist geometry with regional themes: town meetings, snowy fields, silent factories. They seem to ask: Can abstraction contain place? Can regionalism resist sentimentality?

This was the central question for many of Vermont’s avant-garde outsiders. They were not interested in painting the landscape as it appeared—they wanted to translate its rhythms, tensions, and silences into new forms. The state’s natural beauty was a challenge, not a subject. To work abstractly in Vermont required a refusal to flatter, a commitment to looking inward.

The spiritual geometries of Emily Mason

In the 1960s and ’70s, Vermont became home to Emily Mason, daughter of Alice Trumbull Mason (a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group) and herself a brilliant, color-driven abstractionist. Though she maintained a New York studio for much of her life, Mason spent her summers in Brattleboro, where she maintained a second studio in a barn high on a wooded hill. There, she produced canvases that hovered between lyricism and geometry, between landscape and emotion.

Mason’s paintings are often described as abstract landscapes, but that’s misleading. They do not depict Vermont—they absorb it. The colors—lavender, moss, ochre, smoke—feel like distillations of Vermont’s seasonal palette. Her compositions resist fixed perspective; instead, they pulse, drift, and gather like weather. The land becomes atmosphere; the eye moves without anchoring. This refusal to “place” the viewer is central to her work.

What set Mason apart from many of her contemporaries was her ability to reconcile formal rigor with sensual spontaneity. Her brushwork, while fluid, was never casual. Each veil of color was considered, each transition felt. And while her work was deeply modernist in structure, it retained a mystical dimension—something not reducible to theory or technique. In Vermont, she found the conditions to let that balance unfold. The barn became more than a workspace. It was a retreat, a crucible, a high-windowed engine of slowness.

In interviews, Mason spoke of Vermont not as inspiration, but as necessity. Its silence helped her listen. Its light clarified decisions. Its hills created a rhythm in her body that translated, somehow, into the canvas. This relationship—between physical place and internal calibration—is perhaps the most important gift Vermont gave to the avant-garde: not content, but condition.

Three ideas shaped this strain of Vermont abstraction:

- Art as interior landscape, where emotion and perception are inseparable.

- Place as tempo, not subject—rural life as a means of recalibrating artistic time.

- Solitude as structure, where isolation was not retreat but scaffolding for depth.

These artists did not form schools or make manifestos. They made work—slowly, insistently, away from the spotlight. And in doing so, they forged a kind of avant-garde that was not oppositional, but rooted. Not loud, but irrevocably original.

Isolation as incubation

By the 1970s, Vermont had accumulated a critical mass of serious abstract and experimental artists. Yet it had no unified style, no shared program. What it had was atmosphere: barns filled with stretched canvas and jazz records, schoolhouses converted into print studios, former sheep pastures where sculptures quietly rusted in the rain. The state became not a scene, but a system—an ecology of artists who sustained each other not through markets or movements, but through proximity and respect.

One sees this in the trajectory of the painter Frank Stella, who spent time in Vermont during his transition from hard-edge abstraction to more sculptural and environmental forms. Though Stella is not considered a Vermont artist, his time in the state coincided with a loosening of form—a sense that space could be active, participatory, less confined. Whether Vermont influenced this shift is hard to prove. But the timing suggests something: even for the most metropolitan of artists, the state offered a mental clearing.

This period also saw the emergence of small alternative galleries and artist-run spaces—often in barns, attics, and general stores. These were not commercial ventures. They were laboratories. Exhibitions were uncurated, critiques informal, reputations irrelevant. An artist might show a set of shaped canvases alongside a neighbor’s handmade toys. The result was a freedom that urban artists increasingly craved but could rarely access. In Vermont, irrelevance could be fertile.

This ethos survives in the stories artists tell: of painting for no one, of abandoning style to find pace, of learning to live with ambiguity. The isolation that many feared in Vermont—geographic, social, professional—became, for some, the condition of artistic rebirth.

Not all who came flourished. Some artists found the silence oppressive. Others struggled with poverty, loneliness, or lack of recognition. But for those who stayed, the rewards were profound: depth over visibility, honesty over success.

Vermont’s avant-garde, then, was never a style. It was a stance. It said: let the barn be enough. Let the season dictate tempo. Let abstraction arise from daily life. And let art, finally, be less about display—and more about living with the unknown.

Chapter 8: Counterculture on Canvas: Vermont and the Art of the 1960s–70s Back-to-the-Land Movement

Goddard College and experimental education

When the back-to-the-land movement surged in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Vermont emerged as one of its most potent destinations—not only for young homesteaders and idealists fleeing cities, but also for artists eager to reimagine the function, setting, and politics of creative work. The Green Mountains offered cheap land, disconnection from the mainstream, and a sense of temporal remove that seemed to promise authenticity. At the heart of this convergence was Goddard College, a small, progressive institution in Plainfield that played an outsized role in fostering a radical rethinking of art, education, and community.

Founded in 1938 but transformed during the 1960s under a wave of experimental pedagogues and countercultural thinkers, Goddard became a national magnet for those questioning not just what art should be, but what it should do. The college’s low-residency model and self-directed curriculum attracted students and faculty from across the country—among them performance artists, poets, printmakers, musicians, and filmmakers—all drawn by the promise of a space where life and art could be indistinguishable.

In these woods and farmhouses, art was less a profession than a mode of inquiry. Students might construct site-specific sculptures from saplings, collaborate on sound-based rituals in abandoned barns, or produce zines on the college’s ramshackle letterpress. The value lay in process, not product; in intention, not permanence. Influences ranged from John Cage and Allan Kaprow to Buddhist practice and local agricultural rhythms. Nature wasn’t merely subject—it was collaborator, stage, material, and constraint.

This spirit of experimentation radiated outward from the college. Former students and faculty formed communes, print collectives, and traveling performance troupes. The central Vermont town of Montpelier became a hub for handmade publications and radical graphics. Plainfield hosted poster-making workshops where art met protest in hand-inked immediacy. The assumption was not that one had to choose between political urgency and artistic integrity—they were often one and the same.

Three core principles emerged from this intersection of education and counterculture:

- Decentralization: Artistic authority was redistributed away from institutions and experts and toward lived experience and shared authorship.

- Integration: Art was not separate from work, parenting, farming, or protest—it was woven into everyday practice.

- Ephemerality: Much of the art made during this period was deliberately temporary, site-bound, or undocumented—valued for its presence rather than its longevity.

In many ways, this movement built on Vermont’s older artistic traditions of solitude and small-scale making. But now, the motive was political as well as personal. Artists weren’t just leaving the art world behind—they were trying to imagine a different one.

Printmaking, protest, and pastoral revival

While painting and sculpture remained present in Vermont’s 1970s art scene, the dominant medium of the countercultural period was print. Silk-screening, woodblock, and linocut proliferated—cheap, democratic, reproducible methods well-suited to small groups with strong opinions and little funding. Vermont’s print collectives, often housed in converted barns or co-ops, produced everything from protest posters and community newspapers to artist books and educational diagrams.

One of the most influential centers was the Vermont Print and Paper Cooperative, which emerged out of Goddard circles and included artists committed to combining environmental awareness with visual activism. Their output ranged from field guides to radical ecology to stark anti-nuclear posters, often printed on handmade paper using soy-based inks. The aesthetic was rugged and sincere—drawing on folk art, punk zines, and Shaker design all at once.

This revival of handcraft extended beyond the printed page. Artists revived older forms such as hand-dyeing, weaving, soap-making, and basketry—not as nostalgic hobbies but as intentional disruptions of mass production. These crafts were political: they embodied autonomy, anti-capitalism, and a refusal to outsource labor or beauty. A Vermont-made quilt could function both as warmth and as ideological manifesto.

Artists also embraced the seasonal rhythms of rural life, using natural materials in their work or timing projects to planting, harvest, and thaw. Some built land-based installations from branches, snow, or stones—early echoes of what would later be called environmental or eco-art. Others kept sketchbooks filled with crop rotations and chicken coop schematics beside poetic observations of birdsong or snowfall. Art became indistinct from the act of living attentively.

Three recurring visual motifs emerged during this era:

- Solar motifs: sunbursts, radiant faces, and spiral forms referencing energy, growth, and cycles.

- Hands and tools: drawn or carved representations of saws, scythes, and human hands—symbols of embodied labor.

- Plants in motion: vines, roots, and windblown stalks, evoking nature not as backdrop but as an active participant.

These images, while seemingly humble, carried a quiet radicalism. They challenged the urban modernist assumption that innovation required rupture. Instead, Vermont’s countercultural artists proposed that innovation could come from return—from composting older forms and finding, within them, something new.

Psychedelic woodcuts and feminist crafts

Not all Vermont art of the ’70s was pastoral or plain. For a subset of artists steeped in the psychedelic and feminist movements, the state’s remoteness offered space to experiment with ecstatic form, ritualized making, and visual disruption. Woodcuts and linocuts—traditionally tools of populist imagery—were recharged with surreal color schemes and visionary patterning. The woods of Vermont became dreamscapes: swirling, burning, pulsing with vegetal erotics and cosmic satire.

One particularly influential figure in this vein was Rowan Brennan, an elusive artist whose silkscreened scrolls—some over 20 feet long—combined Vermont landscapes with wild phantasmagoria: sunflowers with human faces, moose antlers sprouting galaxies, hay bales made of eyes. Brennan’s work, distributed mainly through underground shows and barter networks, was at once joyful and unsettling. It suggested that nature was not just restorative—it was volatile, unknowable, and weird.

Women’s art collectives during this era also used traditional materials in subversive ways. Knitting circles became feminist consciousness-raising spaces. Embroidery was used to narrate reproductive struggles or political satire. One Vermont group, Threadbare, staged performance-quiltings in which panels were sewn live during storytelling sessions—turning the act of sewing into both theater and testimony.

These artists challenged the gendered assumptions baked into both modernist aesthetics and rural life. They insisted that softness, repetition, and domestic scale could carry fierce energy. Their works were rarely acquired by museums or written into formal histories, but they circulated widely—on walls, clotheslines, and zine pages—and left lasting marks on Vermont’s cultural soil.

More than a style, their work embodied a stance:

- That sincerity was not naivety.

- That beauty could carry political charge.

- That art might live in utility, in ritual, in joy.

This legacy still pulses through Vermont today—not in curated retrospectives, but in informal gallery spaces, farm stands hung with prints, and community studios where art is still made slowly, and together.

Chapter 9: The Studio School Ethos: Vermont as a Model for Alternative Art Education

Bread and Puppet Theater’s visual legacy

If Vermont in the 1960s and ’70s became a sanctuary for artists fleeing urban centers, it also became a proving ground for new models of education—ways of learning that refused hierarchy, de-emphasized accreditation, and prioritized direct experience. No institution embodied this ethos more vividly—or more dramatically—than Bread and Puppet Theater, founded by German-born artist and puppeteer Peter Schumann. Though nominally a theater group, Bread and Puppet functioned as a radical art school without walls, using Vermont’s fields, barns, and gravel roads as its classrooms.

Schumann and his collaborators arrived in Vermont in the early 1970s after several itinerant years in New York, bringing with them a fusion of political performance, folk ritual, and visual spectacle. They settled in Glover, in Vermont’s remote Northeast Kingdom, and began building their own campus from scrap lumber and community labor. Over time, they constructed a museum, rehearsal space, and open-air performance grounds—all adorned with towering papier-mâché figures, bannered barns, hand-painted signs, and sculptural altars made from discarded industrial parts.

Bread and Puppet’s visual language was unmistakable: large, rough-hewn, and expressive, combining medieval grotesquerie with agitprop urgency. Enormous puppet heads, many several feet tall, bore exaggerated features and melancholic gazes. Procession banners stretched fifty feet across, painted with spare figural scenes and bold slogans. Every summer, their Domestic Resurrection Circus—part passion play, part political satire, part harvest festival—drew thousands to Glover’s fields, transforming a hilltop into an ephemeral art metropolis.

The visual impact of Bread and Puppet on Vermont’s art culture cannot be overstated. Their work, though ephemeral by nature, shifted the scale of what rural art could be. It proved that large-scale, collaborative, deeply handmade visual environments were possible outside of cities, museums, or markets. More importantly, it modeled a pedagogy of immersion—where one learned by doing, and where making was inseparable from performance, politics, and food (Schumann famously served sourdough bread at every performance).

This approach influenced generations of artists who passed through Glover or collaborated with the troupe, as well as countless others who adopted its principles without ever stepping foot there:

- Art as public ritual: Bread and Puppet reframed artistic production as an act of communal meaning-making, drawing on pageantry, spirituality, and collective grief.

- Pedagogy through immersion: There were no formal classes, only process—building puppets, painting banners, repairing masks, cooking for the crowd.

- Anti-perfectionism as principle: The roughness of the work was not a flaw but a feature—a statement against commercial polish and in favor of immediacy.

Even now, long after its most radical heyday, Bread and Puppet continues to animate Vermont’s artistic spirit. Its model of education—decentralized, tactile, principled—has become one of the state’s defining exports.

The Putney School, Bennington College, and radical pedagogy

Beyond grassroots movements like Bread and Puppet, Vermont also fostered formal institutions that reimagined what an arts education could look like. Chief among these were The Putney School and Bennington College, two institutions that, while vastly different in scale and philosophy, shared a commitment to integrating creative work with intellectual inquiry and everyday labor.

The Putney School, founded in 1935 by progressive educator Carmelita Hinton, was a boarding high school built around a radical curriculum: one that emphasized arts, farming, and self-governance equally. Students milked cows at dawn, painted watercolors in the afternoon, and debated Tolstoy at night. From its inception, Putney refused the separation of academic and artistic life. The art studios were central—not peripheral—to campus design. Woodworking, printmaking, and music were considered as essential as science or literature.

Putney’s model rested on two convictions. First, that young people could handle serious artistic work. And second, that manual labor deepened intellectual and creative capacity. Many of its graduates went on to influential careers in the arts, including sculptor Joel Shapiro and photographer Wendy Ewald. But perhaps more important was the way the school’s ethos rippled outward. Visiting artists often stayed to teach or collaborate; students returned to Vermont as adults to build studios or start schools of their own.

Bennington College, founded in 1932, offered a college-level analog to Putney’s ideals. From the start, Bennington hired working artists as faculty—people like composer Henry Brant, painter Paul Feeley, and dancer Martha Graham—and encouraged students to pursue cross-disciplinary projects without fixed majors. Its legendary Visual and Performing Arts Program, particularly in the 1940s through the 1970s, treated art not as a field of study but as a mode of life.

Bennington’s approach combined academic freedom with rigorous critique. Students were expected to produce original work from the first year, to think across boundaries, and to develop a sustained independent voice. The result was an unusually high density of committed, self-directed young artists who treated Vermont not as a quiet refuge but as a testing ground.

Both institutions emphasized three overlapping values:

- Creative autonomy: Students were expected to chart their own artistic path, often with minimal instruction but maximum responsibility.

- Community accountability: Artistic work was always in dialogue with others—through critique, collaboration, or shared labor.

- Place-based practice: The land, seasons, and social fabric of Vermont were never just background—they were part of the curriculum.

Together, these schools helped seed Vermont with artists who didn’t just come to visit—they came to stay, teach, and reinvent the structures through which art was taught and valued.

Making by hand, teaching by heart

If Vermont’s art education in this period had a single defining feature, it was the primacy of the hand—the belief that making things with one’s hands was essential not just to art, but to thinking, knowing, and living. Whether in a rural schoolhouse, a performance troupe, or a small college classroom, the ethos was the same: ideas were not enough. You had to build them.

This belief gave rise to a proliferation of studio schools, informal residencies, and short-term workshops across the state. In Craftsbury, a group of woodworkers established The Craftsbury Apprenticeship Program, pairing master artisans with young makers in an intimate, practice-based exchange. In Randolph, the White River Print Studio opened its presses to all comers—combining technical instruction with philosophical conversation. These places were not branded institutions. They were rooms with tools, heated by woodstove, filled with paper dust and pigment fumes. They taught through presence.

The model appealed to artists disillusioned with academic systems or market logics. A Vermont studio school didn’t promise fame. It promised time. And a bench. And someone who would notice if you stopped working.

This educational atmosphere shaped a generation of artists who carried Vermont’s ethos with them—even when they left. Their works, often tactile and modest in scale, carried the trace of these rooms: hand-pulled prints, hand-bound books, handwoven tapestries. They didn’t shout. They held.

And they whispered a quiet proposition: that art, at its best, is not a product of isolation or genius, but of shared attention—between teacher and student, between hand and material, between body and place.

Chapter 10: Snowlight and Silence: Photography and the New England Gaze

Paul Caponigro and the metaphysics of landscape

Among the most enduring contributions to Vermont’s visual legacy are its photographs—images that have circulated more widely, and perhaps more powerfully, than any painting or print. In part, this is due to Vermont’s natural suitability as a photographic subject: its long shadows, its mutable weather, its stark contrasts between field and forest, sky and roofline. But the deeper story lies in the way certain photographers—especially in the post-war era—developed a distinctly New England gaze, defined not by documentary realism but by restraint, reverence, and silence. And perhaps no photographer exemplified this better than Paul Caponigro.

Caponigro, born in Boston in 1932, moved to Vermont in the 1960s and remained for decades, finding in its landscape something close to spiritual sustenance. His photographs—often taken with a large-format camera, printed with exacting silver clarity—do not present Vermont as picturesque or quaint. They present it as sacred. A simple stand of birches becomes an altar. A weathered gravestone holds the silence of centuries. A stream vanishes into snow-covered earth, as if returning to some primal source.

These are not sentimental images. They are devotional. Caponigro once said, “The spirit of a place reveals itself when you’re still enough to listen.” His Vermont images are acts of listening, waiting, allowing. There is no manipulation, no theatrical lighting, no imposed drama. Just an almost liturgical fidelity to what is there.

This approach had a profound influence on younger photographers and on Vermont’s broader visual culture. Caponigro’s refusal to treat the landscape as spectacle challenged the more familiar tropes of New England photography—barns in blazing foliage, ski slopes under blue skies. His Vermont was slower, harder, more interior.

Three characteristics define his metaphysical landscape work:

- Minimalism of form: compositions stripped to essentials, often only two or three elements per frame.

- Tonal restraint: muted greys, softened whites, deep blacks—a palette of quiet intensities.

- Temporal ambiguity: no markers of season or hour, only the eternal now of the still image.

In a state that prizes restraint, Caponigro found a perfect visual grammar. His work doesn’t just show Vermont—it teaches you how to see it.

Seasonal tonalities and rural quiet

The seasons in Vermont are not merely a backdrop. They dictate how life unfolds—and, by extension, how it looks. Winter brings a whiteness that consumes all detail. Spring arrives not with blossoms, but with mud and shadow. Summer is brief, golden, and thick. Fall, while famed for its color, is also sharp-edged, a prelude to withdrawal. Photographers working in Vermont have long understood that to capture the state faithfully requires more than technical skill. It requires rhythm.

The photographer George A. Tice, though based in New Jersey, spent time photographing rural New England in the 1970s and ’80s. His images of Vermont towns—white clapboard churches against grey skies, single-car garages backed by mountains—are unadorned, direct, and free of nostalgia. There’s no visual flattery, only attention. The light is flat. The streets are empty. Yet within this simplicity lies a quiet density. You sense time stacking up like firewood.

Vermont-born photographers such as Mackenzie Greer and Caleb Kenna have carried this tradition into the 21st century. Greer’s large-format color images explore the subtle distortions of weather and season—fog blurring the line between meadow and forest, slush obscuring the edges of a dirt road. Kenna’s drone photography, by contrast, creates new abstractions from the old terrain: hayfields become brushstrokes, silo shadows turn into calligraphy. Though formally different, both photographers respond to a core Vermont condition: a visual world in which change is constant, but not theatrical.

Many of these photographs exhibit a studied rural quiet—a compositional habit as much as an aesthetic effect. Subjects are often framed with generous negative space. There is little movement, little gesture. Instead, the image waits. This reflects not only visual taste, but cultural ethos. Vermont’s built environment is modest, its weather extreme, its population sparse. Photography here is not about spectacle—it is about restraint. It follows the ethics of its subject.

Three recurring themes organize this rural gaze:

- Human absence: even when structures or paths are present, people are not. Their trace is enough.

- Textural emphasis: snow, wood grain, fog, and rust often dominate the frame more than composition itself.

- Moral neutrality: unlike the romanticism of much landscape photography, Vermont images rarely moralize. They observe.

In this way, photography in Vermont has evolved not as a genre of nature photography or travel photography, but as a form of spatial introspection. The state becomes not a postcard, but a mirror.

The Vermont barn as visual icon

No single structure has appeared more often in Vermont’s visual art—photographic or otherwise—than the barn. Not the manicured, red-sided barn of nostalgia, but the working barn: weathered, slumped, half-abandoned, patched with metal sheets or leaning slightly from frost heave. In the visual vocabulary of Vermont, the barn is not only a building—it is a symbol, a signifier, a relic, and a challenge.

Photographers have long recognized the barn as a kind of vernacular monument: deeply ordinary, yet visually magnetic. Its angles and textures lend themselves to both formal composition and documentary pathos. In the hands of someone like Caponigro, a barn becomes sacred geometry. In the lens of Wright Morris, it becomes a study in entropy and endurance.

But the Vermont barn also complicates the visual myth of rural life. Unlike the picturesque farmhouse, the barn shows labor. It carries scars. It changes constantly—paint peels, boards warp, hay doors stay open through snow. It is less a symbol of what was, and more a record of what is endured.

Many photographers use the barn as a way to test the line between realism and aestheticization. A barn in decay may be beautiful—but why? Is it composition? Color? Or something more—some longing for a past that never quite existed? In Vermont photography, this question remains live. Every barn photo is a reckoning.

This fixation has led to an almost absurd abundance. In state fair exhibits, local calendars, and tourism brochures, barns appear with numbing regularity. And yet, the best images resist cliché. They find in the barn not sentiment, but form. Not nostalgia, but trace.

Three visual strategies define this iconography:

- Side lighting: emphasizing the grain of wood, the dent in the roof, the lean of the sill.

- Close cropping: treating the barn less as a structure than as a texture or rhythm.

- Contextual ambiguity: barns placed against sky or forest with no clear setting, allowing abstraction.

In these hands, the barn becomes more than symbol. It becomes structure—of thought, of time, of eye. And like Vermont itself, it stands half in use, half in memory.

Chapter 11: Subversion in Flannel: Contemporary Art and the Trouble with Regional Identity

Beyond syrup and stone walls