The world of alchemical illustrations is a rich tapestry woven from mystery, mysticism, and spiritual science. Long before chemistry became a modern discipline, alchemy thrived as a sacred pursuit blending natural philosophy, spiritual growth, and the secrets of transformation. The origins of alchemical illustration trace back to ancient Egypt, Greece, and the Islamic world, where early esoteric texts were often preserved and transmitted in symbolic form. One of the most influential sources in this tradition was the Emerald Tablet, attributed to the legendary figure Hermes Trismegistus, a mythic sage believed to have lived sometime around 3000 BC.

Hermes Trismegistus became a central figure in Hermetic philosophy, which influenced both Eastern and Western mystical traditions. His teachings emphasized the unity of the cosmos and the divine connection between mankind and the heavens—a principle often depicted visually through symbolic diagrams. Ancient alchemical imagery drew upon Greek and Roman mythologies, incorporating gods, celestial bodies, and allegorical beasts to represent cosmic processes. Early illustrations were sparse but potent, often appearing in manuscript margins or copied into grimoires that circulated among a small, secretive audience.

Hermetic Roots and the Influence of Ancient Traditions

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 13th centuries AD), alchemical knowledge was preserved and expanded by scholars like Jabir ibn Hayyan (born c. AD 721), whose texts featured some of the earliest structured visual systems in alchemical literature. These ideas were translated into Latin during the 12th century and began to influence European intellectual circles. As alchemy took root in Christian Europe, illustrations became more elaborate, merging classical motifs with medieval religious symbolism. The crucible, for instance, became both a physical tool and a metaphor for the soul’s purification.

These ancient beginnings laid the groundwork for the more sophisticated alchemical artwork of the Renaissance and beyond. Though much of the art remained symbolic and encoded, it also began to reflect a stronger integration of text and image. Illustrators were no longer content with simple borders or standalone symbols—they began creating entire pages of allegorical scenes that combined visual storytelling with philosophical instruction. This shift signaled the dawn of a new era in esoteric imagery: the golden age of alchemical art.

The Golden Age: Renaissance and Early Modern Alchemical Art

From the late 15th to the early 17th century, alchemical illustration entered what many scholars regard as its golden age. It was during this period that alchemical manuscripts and printed books began to include increasingly intricate, full-page engravings filled with layered meanings. The Renaissance, with its rediscovery of classical thought and emphasis on human potential, proved fertile ground for the flowering of esoteric art. Artists and alchemists collaborated closely, creating symbolic images that reflected both spiritual truths and the mysteries of the natural world.

One of the key figures of this era was Heinrich Khunrath, born around 1560 in Dresden. He was a German physician, philosopher, and alchemist whose magnum opus, Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae (The Amphitheater of Eternal Wisdom), was published in 1595. Its detailed engravings, produced with the help of skilled illustrators, are among the most famous in alchemical history. The “Cosmic Rose” and “Laboratory of the Sages” scenes illustrate both internal transformation and the physical laboratory process—a duality at the heart of alchemy.

Visionaries like Heinrich Khunrath and Robert Fludd

Another Renaissance figure of towering importance was Robert Fludd (1574–1637), an English physician and mystic who studied at Oxford University and practiced medicine in London. Fludd’s elaborate engravings, especially in works like Utriusque Cosmi Historia (1617–1621), presented the cosmos as a divine machine, complete with celestial spheres, angelic forces, and microcosmic human forms. His illustrations functioned as philosophical diagrams, each element representing a principle of divine order and transformation. These images were meant not only to inform but to inspire contemplation and spiritual elevation.

Alchemical illustrations from this period were typically engraved on copper plates, allowing for high levels of detail and reproducibility. Collaborations between alchemists, printers, and illustrators became more formalized, often sponsored by wealthy patrons intrigued by esoteric knowledge. The balance between secrecy and revelation remained central—images were layered with symbolism, accessible only to those trained in the Hermetic arts. This period stands as the height of visual alchemy, when art and science were not opposites but two faces of the same divine truth.

Symbolism and Hidden Meanings

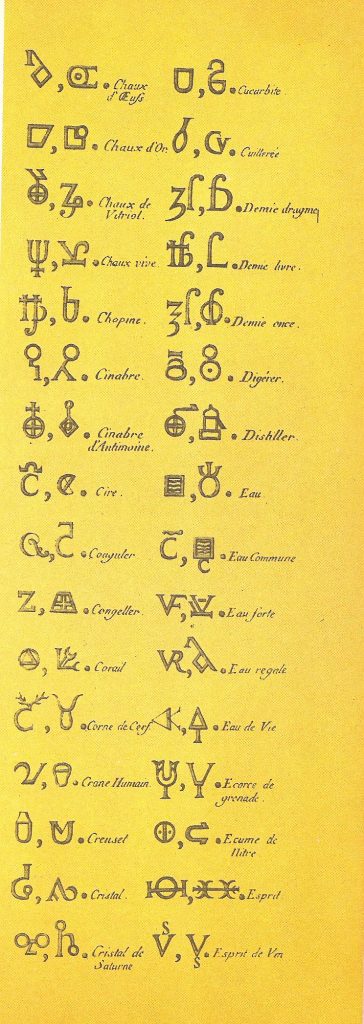

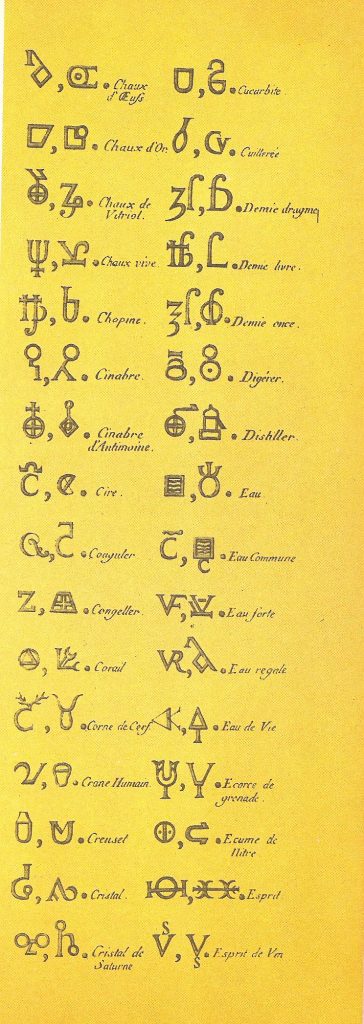

Alchemical illustrations were not merely decorative—they were visual codes, each symbol pointing toward a metaphysical principle or step in the alchemical process. The use of symbolism in these works is one of their most defining features, transforming illustrations into tools of contemplation and instruction. Whether hand-painted or engraved, these artworks employed a consistent visual language rooted in Christian iconography, classical mythology, and esoteric geometry. The combination created a world of symbols that could only be deciphered with careful study and spiritual insight.

Among the most recurring motifs was the ouroboros—a serpent devouring its own tail—which symbolized eternity, cyclical time, and the unity of opposites. The sun and moon often appeared as allegorical representations of the masculine and feminine principles, destined to be conjoined in the sacred marriage known as the coniunctio. Lions, dragons, pelicans, and even fantastical beasts symbolized the challenges and powers encountered along the alchemical path. The seven classical planets were also tied to metals and spiritual stages, aligning the work of the alchemist with the very order of the cosmos.

Common Motifs: Serpents, Suns, and the Ouroboros

Carl Jung, the Swiss psychologist born in 1875 and died in 1961, famously examined these symbols in his seminal work Psychology and Alchemy (1944). Jung believed that alchemical symbolism mirrored the process of individuation—the journey of integrating the unconscious into the conscious self. To Jung, the alchemical marriage and transmutation of base metals into gold symbolized the transformation of the soul into its highest, most unified state. His interpretations brought new relevance to alchemical imagery, especially among 20th-century thinkers and artists seeking deeper spiritual meaning.

Many alchemical symbols carried double meanings—literal for those versed in chemistry, metaphorical for spiritual seekers. For example, the crucible symbolized both the vessel used to purify metals and the suffering necessary to purify the soul. The red lion might represent a chemical reaction or the divine fire of inspiration. Such multivalence made these artworks simultaneously technical manuals and sacred texts, their meanings shifting depending on the viewer’s level of understanding. This layered complexity continues to fascinate viewers and scholars alike.

Famous Manuscripts and Alchemical Codices

Some of the most elaborate and mysterious alchemical illustrations were created not as standalone prints but as part of complete manuscripts and codices. These illuminated books were often created by hand, commissioned by wealthy patrons or compiled by dedicated alchemists. Lavish in design and rich in symbolism, they combined visual and textual instruction to guide initiates through the path of spiritual and material transformation. Among the most famous of these is the Splendor Solis (The Splendor of the Sun), believed to have been created around 1582 in Germany.

Splendor Solis is attributed to Salomon Trismosin, a pseudonymous figure who claimed to be a teacher of Paracelsus, the revolutionary Swiss physician and alchemist. While little is known for certain about Trismosin, manuscripts of Splendor Solis often bear ornate borders, gold leaf accents, and deeply allegorical content. The images portray scenes of kings dissolving in pools, solar twins being birthed from dragons, and alchemical operations taking place in surreal dreamscapes. Every element, from the colors to the placement of figures, is steeped in alchemical meaning.

Splendor Solis and The Rosarium Philosophorum

Another significant manuscript is the Rosarium Philosophorum (The Rosary of the Philosophers), published in 1550 and accompanied by 20 striking woodcut illustrations. This work emphasizes the mystical union of male and female figures as symbolic of the spiritual coniunctio—a vital process in both alchemy and inner transformation. The images, arranged like a visual sermon, follow a spiritual narrative from the initial putrefaction (symbolized by death) to the final rebirth in radiant union. The accompanying Latin texts often offer cryptic phrases that deepen the mystery.

These codices were more than just books—they were sacred objects in themselves. Ownership of such a volume signaled both intellectual prowess and spiritual readiness. While mass-produced books eventually brought alchemical ideas to wider audiences, these manuscripts remained central to elite esoteric circles. Their illustrations offered far more than decoration—they were integral parts of a visual philosophy, designed to teach, conceal, and inspire simultaneously. Today, they are prized by collectors and scholars alike for their beauty and depth.

The Artist-Alchemist: When Art and Practice Intersect

One of the most compelling questions in the study of alchemical illustrations is whether the artists who created them were also initiates in the alchemical arts. In many cases, there was a deliberate blending of the roles of artist and alchemist. Some of the most iconic images came from individuals who practiced both the visual and mystical sciences, or from close partnerships between scholars and illustrators. The secrecy of the alchemical tradition made it difficult to separate myth from biography, but surviving evidence suggests that many artists were deeply immersed in the symbolic language they depicted.

For instance, Heinrich Khunrath’s close involvement in the design of his engravings indicates a hands-on approach to the artistic process. He wasn’t simply commissioning illustrations—he was shaping them according to his spiritual and philosophical vision. Similarly, Robert Fludd is known to have supervised the engravings in his cosmological works, offering detailed instructions to the craftsmen who executed them. This careful guidance ensured that each image functioned as a teaching tool as much as a work of art.

Was the Illustrator Also the Initiate?

In some cases, collaboration was key. The printers and engravers who worked on alchemical books were often initiated into at least the symbolic aspects of the craft. It wasn’t unusual for entire workshops to be steeped in esoteric teachings, especially in cities like Basel and Nuremberg, known for their Hermetic publishing houses. Illustrators were trusted with secret knowledge and expected to preserve its integrity while rendering it visually compelling. The bond between artist and alchemist mirrored the alchemical theme of union—the merging of intellect and craft.

This overlap of roles lent the illustrations a potency rarely found in secular art. Every brushstroke or etched line carried spiritual intention, much like the crafting of a sacred icon. The artist-alchemist wasn’t merely copying scenes from imagination—they were encoding living wisdom. This union of art and initiation helped preserve the tradition even as it passed through periods of persecution and skepticism. Today, these images stand as evidence of a time when to draw was to divine, and to illustrate was to illuminate.

Alchemical Illustration’s Influence on Later Art

While the age of alchemy as a formal discipline began to wane in the 18th century, its visual legacy found new life in the modern era. Artists, mystics, and psychologists of the 19th and 20th centuries began rediscovering the symbolic power of alchemical illustrations. The 20th century, in particular, witnessed a revival of interest in alchemical symbolism, thanks in large part to the work of Carl Jung. Jung’s psychological framework reinterpreted alchemy as a metaphor for the inner journey of the soul, making it newly relevant to a generation seeking meaning in a mechanized world.

Jung’s influence extended far beyond the realm of psychology. Surrealist artists such as Max Ernst (1891–1976) and Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) began incorporating alchemical symbols into their dreamlike compositions. Ernst’s The Robing of the Bride and Carrington’s The Lovers are imbued with mythic and esoteric references drawn directly from alchemical lore. Their works are less literal than Renaissance engravings but echo the same themes of transformation, duality, and inner awakening. These modern artists treated alchemy not as pseudoscience but as spiritual mythos.

Surrealism, Jung, and Modern Occult Art

The 20th-century occult revival—fueled by groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and later New Age movements—also embraced alchemical imagery. Tarot decks such as the Thoth Tarot (1943) by Aleister Crowley and Lady Frieda Harris utilized rich alchemical symbolism to express metaphysical concepts. In the postwar era, esoteric publishers reprinted classic alchemical texts and illustrations, introducing them to a broader audience of artists and seekers. Graphic designers, tattoo artists, and even filmmakers began drawing from the rich visual vocabulary of alchemy.

Today, alchemical art continues to inspire creators across mediums. Digital illustrators use the old motifs—serpents, flasks, cosmic trees—in entirely new formats. Alchemical ideas have surfaced in films like The Holy Mountain (1973) and Doctor Strange (2016), as well as in video games, album covers, and high fashion. The essence of alchemical illustration—its mystery, complexity, and spiritual ambition—has proven remarkably adaptable to modern aesthetics. These visual echoes ensure that alchemy’s artistic legacy is far from forgotten.

The Enduring Mystery and Legacy of Alchemical Imagery

Despite centuries of change, the core appeal of alchemical illustrations remains strong. These works are more than historical oddities—they are profound visual meditations on human transformation. Whether depicting the stages of distillation or the allegorical union of opposites, alchemical images speak to timeless themes. They reveal the spiritual longing at the heart of Western tradition, a yearning for purity, unity, and divine wisdom.

Part of their mystery lies in their refusal to be pinned down to a single interpretation. Like Scripture or poetry, they reveal different truths depending on the viewer’s knowledge and perspective. Some see chemical procedures; others see the journey of the soul; still others see both. This ambiguity is not a flaw but a feature, allowing the artwork to engage the mind and the spirit simultaneously.

Why These Images Still Captivate Us

In a world saturated with literalism and surface-level content, the depth of alchemical illustration stands as a counterpoint. These images invite us to slow down, reflect, and engage in symbolic thinking. They awaken an ancient part of the imagination—one attuned to mystery and spiritual significance. For many, discovering these works is like stumbling upon a lost language waiting to be decoded.

Their legacy lives on not just in museums and rare book collections, but in the minds and studios of modern seekers. Whether through art, meditation, or study, the symbols of alchemy continue to guide those drawn to the inner path. The mystery remains intact, whispering truths across centuries. In a world that has forgotten how to wonder, alchemical art offers an open door to transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Alchemical illustrations blend art, spirituality, and early science through symbolic imagery.

- Renaissance figures like Heinrich Khunrath and Robert Fludd pioneered rich visual esotericism.

- Manuscripts like Splendor Solis and Rosarium Philosophorum remain iconic examples.

- Artists often doubled as alchemists or worked in close spiritual collaboration.

- Alchemical motifs continue influencing psychology, modern art, and spiritual traditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the ouroboros in alchemical illustrations?

It’s a snake eating its own tail, symbolizing eternity and cyclical transformation. - Who created the Splendor Solis manuscript?

It’s attributed to Salomon Trismosin, a legendary alchemist from the 16th century. - How did Carl Jung interpret alchemical symbols?

He viewed them as metaphors for psychological and spiritual transformation. - Were alchemical illustrators actual alchemists?

In many cases, yes—or they worked closely with alchemists and initiates. - Does alchemical art still influence modern culture?

Yes, it appears in surrealist art, Tarot, films, and esoteric spiritual circles.