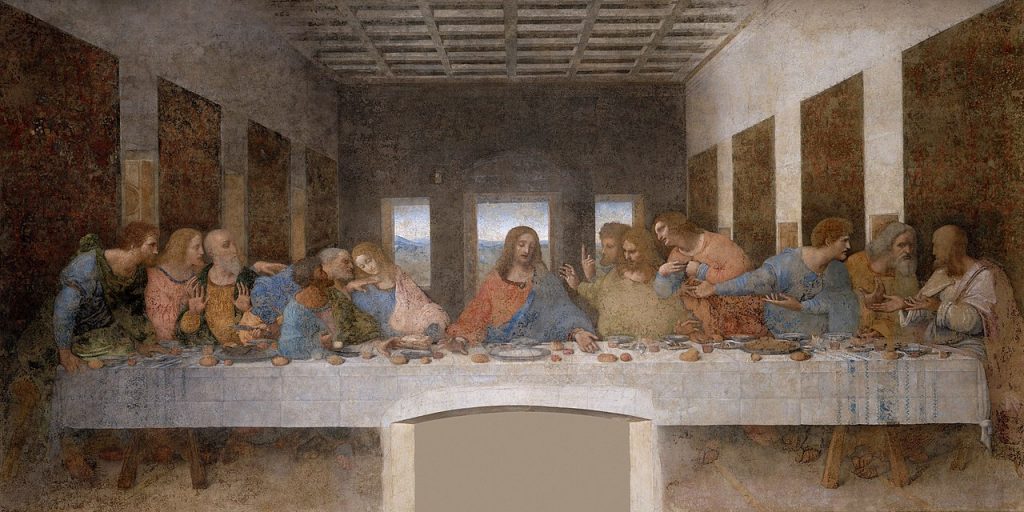

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper stands among the most iconic images in Western art. Painted between 1495 and 1498 on the wall of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, this mural does more than illustrate a sacred meal. It captures a spiritual and psychological drama unfolding in real time—every glance, gesture, and grimace teems with tension. What appears to be a single snapshot of a biblical moment is, in truth, a masterpiece of narrative and subtle symbolism.

Unlike other religious art of its time, Leonardo’s version of the Last Supper emphasizes human emotion and relational dynamics. This was not a typical interpretation of the Gospel scene. Earlier works often showed the apostles sitting stiffly in a line, calmly receiving Christ’s words. Leonardo, in contrast, chose to portray the instant after Jesus announces that one among them will betray him. The reactions ripple outward, frozen forever in expressions of shock, denial, sorrow, and accusation.

There is a haunting intimacy in the figures. Their faces—carefully rendered, unique, and alive—each suggest a deeper inner world. Many viewers over the centuries have suspected there’s more here than meets the eye. Who are these men, really? What do their expressions betray? Could Leonardo have hidden messages or meanings within their forms? These questions have led generations of art lovers, historians, and even novelists to look for hidden faces and layered stories in the mural.

This is a work where silence speaks volumes. Though painted on a deteriorating wall over 500 years ago, The Last Supper continues to draw people in—not just for what it shows, but for what it seems to conceal.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vision and Method

Leonardo da Vinci approached painting as a form of scientific inquiry. His goal wasn’t just to illustrate a story—it was to understand and express the inner life of human beings through visual form. Long before he began painting The Last Supper, he studied anatomy through dissection, keenly observing the muscles of the face and body to understand how emotion manifested physically. This obsession with lifelike expression would shape every figure in the mural.

He did not use standard techniques of fresco painting for this commission. Instead of painting directly into wet plaster, Leonardo experimented with tempera and oil-based paints on a dry wall—hoping this would give him more time to achieve detail and subtle shading. While this approach allowed for remarkable depth and nuance in the faces and gestures of the apostles, it also made the mural unusually fragile. The technique proved disastrous for preservation, as the paint began to flake away within decades of completion.

Leonardo worked slowly and deliberately. Giorgio Vasari, the Renaissance biographer, recorded how Leonardo would sometimes stare at the wall for hours, contemplating before applying a single brushstroke. He also reportedly used live models from the streets of Milan, carefully selecting faces that matched the emotional tone he wished to convey for each apostle. Rather than painting idealized saints, Leonardo brought a raw humanity to the men around Christ.

His focus on composition was also groundbreaking. Leonardo grouped the apostles into four clusters of three, forming a visual rhythm across the table. The vanishing point centers on Christ’s right temple, drawing the viewer’s eye to the calm amid the chaos. But it’s the apostles’ faces—their minute twitches, raised brows, clenched jaws—that truly animate the scene and invite closer inspection.

Identifying the Apostles: Tradition vs. Theory

The identities of the apostles in The Last Supper have largely been established based on tradition, with guidance from Leonardo’s preparatory sketches and writings by early commentators. From left to right, the typical identification runs as follows: Bartholomew, James the Less, Andrew, Judas Iscariot, Peter, John, Jesus at the center, then Thomas, James the Greater, Philip, Matthew, Thaddeus (Jude), and Simon the Zealot. However, not every figure is universally agreed upon, and some positions—especially near the center—have sparked debate.

One major source of ambiguity is the absence of inscriptions or haloes, which were common in earlier depictions to distinguish the apostles. Leonardo deliberately removed those identifiers, challenging viewers to rely on visual cues alone. This artistic choice has led to occasional confusion, especially regarding the trio seated to Jesus’s right—Peter, John, and Judas. Their tightly interlocked positions and contrasting gestures fuel interpretive speculation.

Some scholars propose that Leonardo may have intentionally left the identities of certain apostles vague to shift the focus from individual recognition to emotional resonance. In this reading, the emphasis is not on who each apostle is, but on what they feel in response to Jesus’s statement. This aligns with Leonardo’s broader humanist approach, which valued the expression of inner truth over literal representation.

Still, traditional identification remains the most widely accepted framework, supported by centuries of analysis and comparison with da Vinci’s own notebooks. Below is a commonly accepted list of the apostles from left to right:

- Bartholomew

- James the Less

- Andrew

- Judas Iscariot

- Peter

- John

- Jesus

- Thomas

- James the Greater

- Philip

- Matthew

- Thaddeus (Jude)

- Simon the Zealot

Understanding who’s who helps us see how each reaction is tailored—facially and physically—to their role in the Gospel narrative and in Leonardo’s vision.

Judas Iscariot: Shadowed and Separated

Among the apostles, none stands out—or sinks deeper—than Judas Iscariot. Leonardo painted him leaning back into shadow, his face tense and scowling. Unlike the others, who react outwardly to Jesus’s words, Judas appears almost detached. His expression is inward, as if bracing for the moment he knows is coming. This contrast marks him as the betrayer without need for labels or overt condemnation.

Judas is positioned beside Peter and John, in the same grouping as Jesus—a break from traditional portrayals, which often placed him isolated or alone on the far side of the table. Leonardo’s decision to keep Judas among the group made the betrayal more intimate and tragic. It reinforces the idea that the betrayal came from within Christ’s inner circle, not from an outsider. This heightens the emotional gravity of the scene.

Subtle symbols surround Judas. His hand clutches a small bag—commonly interpreted as the silver he was paid for the betrayal. His other hand reaches toward the same dish as Jesus, echoing the Gospel of Matthew 26:23: “He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me.” Adding to the foreboding, Judas has knocked over a small container of salt—a traditional symbol of bad luck or broken covenant in Renaissance Europe.

The shadow obscuring Judas’s face adds to the sense of hidden guilt. His expression is not theatrical but internalized—his brow furrowed, mouth slightly tightened. Some viewers might miss the full emotional weight of his expression unless they look closely. In this way, Judas becomes one of the painting’s “hidden faces”—his true torment veiled in darkness and subtlety.

The Mysterious Face Beside Jesus

To Jesus’s right sits a figure long assumed to be the Apostle John. This figure has a delicate face, downcast eyes, and flowing auburn hair, leading some to suggest it’s not John at all, but Mary Magdalene. This theory gained worldwide attention after the publication of The Da Vinci Code in 2003, in which author Dan Brown argued that Leonardo embedded Mary as a hidden companion to Christ. While sensational, this idea isn’t new—it echoes claims made by art theorists as early as the 19th century.

Supporters of the Mary Magdalene theory point to the figure’s feminized features and body language. The person leans away from Jesus with an expression of sorrow or reverence, while Peter, just behind, appears to be making a cutting gesture with a knife and whispering to the figure. The visual proximity and body language have fueled theories of a secret relationship or coded narrative. Some even suggest the “V” shape formed between Jesus and this figure symbolizes the feminine divine or sacred union.

Art historians overwhelmingly reject the Mary Magdalene interpretation. Renaissance tradition consistently portrayed John the Evangelist as youthful and effeminate, reflecting his identity as the “beloved disciple” and his relatively young age compared to the others. Leonardo followed this tradition in other works, including his Saint John the Baptist. Moreover, no documented evidence supports the idea that Leonardo intended to include Mary Magdalene among the twelve.

Still, the figure’s ambiguous appearance invites contemplation. Whether John or someone else, this apostle’s serene, sorrowful demeanor forms a visual counterpoint to the turmoil around him. The softness of the features and the calm expression draw viewers in, asking them to consider the deeper layers of identity and devotion.

Emotions Etched in Paint: Faces in Motion

Leonardo’s apostles are not just sitting—they’re responding. Their faces and gestures convey a spectrum of emotion that animates the scene like a theatrical production. Each group of three apostles forms a dynamic cluster of dialogue and reaction. The first trio on the left recoils in disbelief; the middle-left cluster debates urgently; the group to Jesus’s immediate right swirls with internal tension; and the far-right group appears stunned, struggling to understand.

These emotional cues are most visible in the apostles’ faces. Andrew raises both hands, brows arched in surprise. Peter scowls and leans forward, face tight with defensiveness. Thomas points upward with a questioning look, his eyebrows drawn. Philip presses both hands to his chest, eyes wide with hurt. Each face is unique, capturing a fleeting, complex moment of spiritual reckoning.

Leonardo achieved this emotional realism through extensive anatomical studies. His notebooks include dozens of sketches showing the effects of emotion on the human face—wrinkled brows, stretched mouths, and twitching muscles. He studied how sorrow pulls the corners of the eyes down and how fear tightens the jaw. These observations translated directly into the apostles’ expressions in The Last Supper.

Among the most memorable faces are those of Peter, Thomas, and Philip. Peter’s scowl radiates protectiveness; Thomas’s raised finger foreshadows his later doubt; Philip’s open palms seem to plead his innocence. Together, they form a rich emotional chorus that brings the Gospel text to life visually, even for those unfamiliar with the scripture.

Peter’s Anger and the Knife

Peter sits just behind John, partially obscured but very much present. His expression is tight with suspicion, and he leans forward aggressively. In his right hand, he grips a small knife—an often-overlooked detail that carries significant symbolic weight. The weapon could foreshadow the moment in the Garden of Gethsemane when Peter slices off the ear of a Roman soldier (John 18:10), demonstrating both his loyalty and impulsive nature.

The inclusion of the knife has prompted various interpretations. Some see it as a literal narrative reference, while others view it as an emblem of Peter’s temperamental character. Leonardo may have intended it to serve both functions—both as prophecy and personality clue. The blade also intersects visually with Judas’s back, creating a line of tension between the two. Though subtle, this compositional detail adds to the emotional friction in the scene.

Peter’s face is partially hidden, which adds to his status as a “hidden face” in the mural. Unlike Judas, whose darkness implies guilt, Peter’s obscurity suggests the volatility of devotion. He is at once close to Jesus and capable of rash, violent acts. His eyes are narrowed, focused not on Jesus but perhaps on the murmurs between John and Judas, reinforcing his role as protector and aggressor.

The spatial proximity between Peter and John has also raised eyebrows. Peter seems to whisper into John’s ear while clutching the knife, creating a moment dense with narrative tension. Is he urging John to ask Jesus who the betrayer is? Is he already plotting confrontation? Leonardo leaves these questions unanswered, inviting endless speculation through the careful placement of gesture and gaze.

Thomas the Doubter: A Raised Finger

To Jesus’s left, the figure of Thomas stands with a pointed finger, eyebrows arched, mouth slightly open. This gesture, often overlooked, is rich with meaning. It may reference the later scene in the Gospel of John (20:24–29) where Thomas insists on seeing and touching Christ’s wounds before believing in the Resurrection. In this context, the raised finger becomes a symbol of skepticism and a foreshadowing of spiritual confrontation.

The intensity of Thomas’s expression marks him as a figure of active questioning. His finger points not at Jesus but skyward, suggesting doubt, inquiry, or perhaps an appeal to divine authority. The gesture interrupts the horizontal calm of the composition, creating vertical motion that draws the viewer’s eye upward. His furrowed brow and parted lips suggest urgency and dismay—a man whose faith is shaken even before the betrayal occurs.

Leonardo often used hands and gestures to supplement or even replace facial expression in conveying emotion. In Thomas’s case, the gesture is as loud as a shout. It underscores the psychological complexity Leonardo sought to capture in each apostle. Thomas is not simply shocked—he’s demanding answers.

In portraying Thomas this way, Leonardo departs from more passive interpretations of the disciple. He becomes a symbol of the questioning believer, someone who wrestles openly with faith and doubt. His raised finger reminds viewers that spiritual truth often requires engagement—not blind acceptance.

Lost in Time: Damage and Restoration

Despite its fame, The Last Supper has suffered more than most masterpieces. Leonardo’s experimental technique of painting on dry plaster began deteriorating almost immediately. By the middle of the 16th century, observers reported significant flaking. Humidity, pollution, and even a door cut into the wall in the 1600s further damaged the work. By the 20th century, the painting was nearly unrecognizable.

A series of restoration attempts began as early as 1726, but many caused more harm than good. One of the most invasive restorations occurred in 1770, during which overpainting was applied liberally. Efforts in the 19th century fared no better, with restorers using oil paints and varnishes that darkened the surface and obscured details. Much of the original facial work was lost or distorted during these periods.

The most ambitious and controversial restoration took place from 1978 to 1999. Led by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, the project involved cleaning, removing layers of grime and overpainting, and reapplying watercolors to suggest lost forms. Advanced infrared scanning helped distinguish original brushwork from later additions. While purists criticized the repainting of lost areas, the project revealed long-hidden details, including facial expressions, folds in garments, and Leonardo’s use of color gradients.

Some faces—particularly those of Bartholomew and Thaddeus—remain so degraded that they verge on ghostlike. Others, like Jesus, Peter, and Judas, have retained much of their original intensity. This uneven preservation creates an unintended “hidden face” effect—where the passage of time has obscured or erased the emotional depth Leonardo so painstakingly rendered.

Beyond the Visible: Allegory and Faith

Beneath the surface of Leonardo’s Last Supper lies more than a meal or betrayal. It is, at heart, a meditation on human nature, divine mystery, and the fragile line between faith and doubt. Leonardo, influenced by Renaissance humanism, sought to elevate biblical narrative into a philosophical tableau. The varied faces and gestures become reflections of broader themes—loyalty, fear, love, suspicion, and spiritual tension.

Each face invites the viewer to find themselves within the painting. Are we the faithful Philip, the questioning Thomas, the shadowed Judas, or the serene John? In this sense, the apostles become allegorical figures as much as historical ones. The painting becomes a mirror, not just of Christ’s final moments, but of the eternal struggle within every soul to believe, to trust, and to choose.

Leonardo’s spiritual beliefs remain elusive. He was not known for religious fervor, and he often approached theological subjects with intellectual curiosity rather than doctrinal conviction. Yet in this work, he conveys the gravity of the moment with profound empathy. The emotions captured in the faces transcend doctrine, touching something deeply human.

More than five centuries after its creation, The Last Supper continues to whisper its secrets. The hidden faces—some shadowed by paint, others by emotion—remind us that great art is not just seen; it is felt, questioned, and remembered.

Key Takeaways

- Leonardo da Vinci painted The Last Supper between 1495–1498 in Milan, using a fragile technique that led to early deterioration.

- The apostles’ faces and gestures convey layered emotions, from shock to betrayal to silent sorrow.

- Judas Iscariot, partially shadowed and clutching a bag of silver, is portrayed with subtle yet powerful cues of guilt.

- Popular theories—like the Mary Magdalene hypothesis—emerge from visual ambiguities, but lack historical support.

- Despite restoration efforts, many original facial details are lost, deepening the painting’s air of mystery.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Where is The Last Supper located?

It is on the north wall of the refectory in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. - How many apostles are in the painting?

There are twelve apostles depicted alongside Jesus, arranged in groups of three. - Why is the painting so damaged?

Leonardo used an experimental technique that didn’t adhere well to the wall, leading to rapid deterioration. - Who is the figure next to Jesus?

Most scholars identify the figure as John the Apostle, not Mary Magdalene, despite popular theories. - What does the knife in Peter’s hand symbolize?

It likely foreshadows Peter’s violent defense of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane and reflects his impetuous nature.