The word “odalisque” comes from the Turkish term odalık, meaning “chambermaid” or servant in a royal harem. In the Ottoman Empire, odalisques were typically young women assigned to serve in the private quarters of the palace. Their duties were domestic, not romantic or sexual in nature, despite how later artists reimagined them. European travelers misunderstood this role, transforming the figure of the odalisque into a symbol of sensual mystery.

This misunderstanding was amplified in the writings and sketches of 17th- and 18th-century travelers to the Islamic world. Many of these visitors never actually entered harems, relying instead on hearsay or imagination. Their published journals described luxurious interiors, soft silks, reclining women, and private leisure. These fantastical portrayals influenced the European imagination and offered artists new themes for visual indulgence.

By the late 1700s, the figure of the odalisque was being used in Western art as a vehicle for exploring the nude in non-traditional contexts. Instead of placing nudes in mythological or biblical scenes, artists now framed them within an imagined Eastern world. The setting became as important as the figure: cushions, hookahs, veils, and patterned tiles completed the fantasy. These compositions allowed painters to display the nude in a fresh and decorative context.

The odalisque in European art was never about accurately portraying the women of the East. It was a hybrid creation—part classical study, part exotic invention. What began as a misunderstood role was reimagined as a genre. The odalisque became a symbol of repose, elegance, and imagined luxury, providing artists with a new way to engage with traditional themes in alluring, colorful environments.

Ingres and the Idealized Nude

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was born on August 29, 1780, in Montauban, France. His early education in the arts came from his father, a decorative painter and sculptor. In 1797, he entered the studio of Jacques-Louis David in Paris, where he received formal training in Neoclassical methods. By 1801, Ingres had won the prestigious Prix de Rome, which allowed him to study in Italy and absorb the lessons of Renaissance masters.

Between 1806 and 1811, Ingres studied in Rome, where he copied the works of Raphael and others, sharpening his focus on linear precision and calm composition. He developed a lifelong interest in portraying the female figure with elongated forms and serene expressions. His admiration for classical art led to a style that often distorted anatomy for elegance. This was not error, but choice—a pursuit of ideal beauty over natural form.

“La Grande Odalisque” and Classical Influence

In 1814, Ingres completed “La Grande Odalisque,” a reclining nude that became one of his most discussed paintings. The work features a nude woman lounging on a divan, turned away from the viewer with an elongated spine and limbs. Critics noted that the back seemed anatomically impossible, as though she had extra vertebrae. Ingres, however, cared more for grace and rhythm than for anatomical truth.

The painting marked a shift in French art, blending classical techniques with exotic subject matter. Ingres had never visited the East, but borrowed freely from imagined motifs—peacock feathers, silk drapery, and incense burners. Though criticized at the time, the painting gained lasting influence. It became a cornerstone of the odalisque genre, inspiring generations of artists to explore reclining nudes through a similar lens of fantasy and refinement.

Delacroix and the Romantic Movement

Eugène Delacroix was born on April 26, 1798, and became one of the leading figures of French Romanticism. Unlike Ingres, who emphasized control and precision, Delacroix favored emotion, color, and movement. He entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1815 and quickly rose to prominence with his bold, dramatic compositions. In 1832, he traveled to Morocco and Algeria with a diplomatic mission, a journey that deeply shaped his artistic focus.

During this North African trip, Delacroix filled notebooks with sketches of people, interiors, garments, and daily life. These images formed the basis for many later works, in which he aimed to depict not only what he saw, but how he felt. His fascination with the East was rooted in its difference from the French world—its color, pace, and textures provided rich material. His paintings became less about documentation and more about atmosphere.

The Colorful World of “Women of Algiers”

In 1834, Delacroix painted “Women of Algiers in Their Apartment,” based on his North African observations. The painting shows a group of women seated in a richly furnished room, surrounded by patterned walls and textiles. Unlike Ingres’ polished surfaces, Delacroix used loose brushwork and saturated color to evoke mood. His odalisques appear contemplative, not posed, creating a quiet, internal energy.

A second version of the painting was completed between 1847 and 1849, showing a deeper evolution in Delacroix’s use of color and form. These works stood as landmarks in Romantic Orientalism. They moved the odalisque beyond mere study of form into a study of place. For Delacroix, the harem was not just a setting for nudes—it was a space filled with cultural richness, daily life, and ambient mystery, interpreted through the eye of a Romantic painter.

Orientalism in the 19th Century Salon

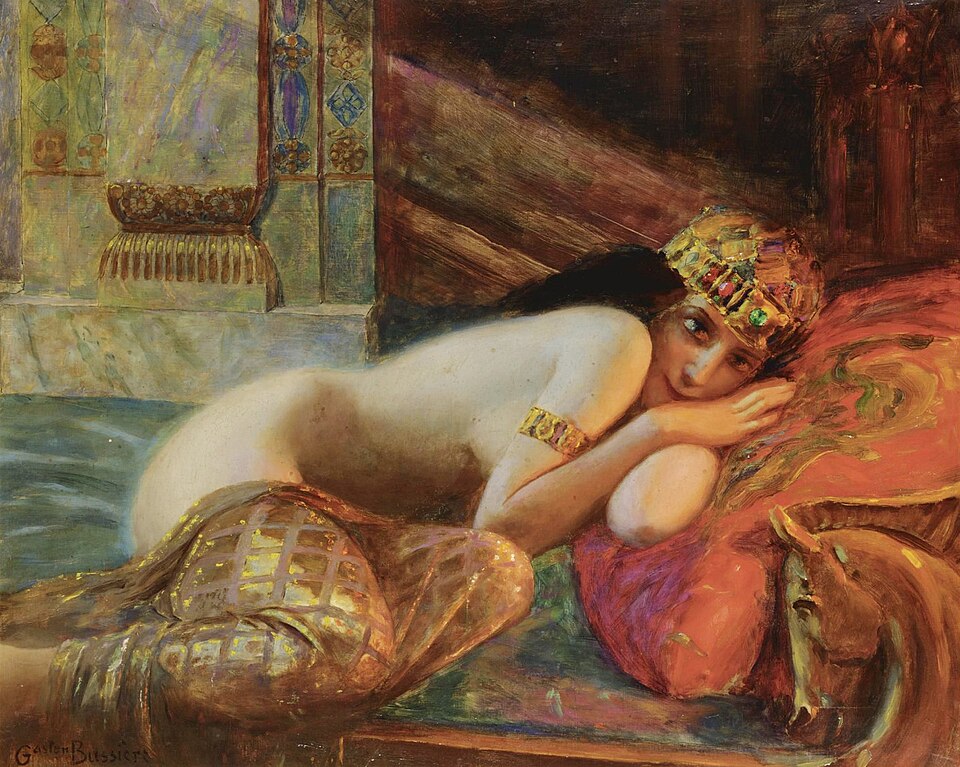

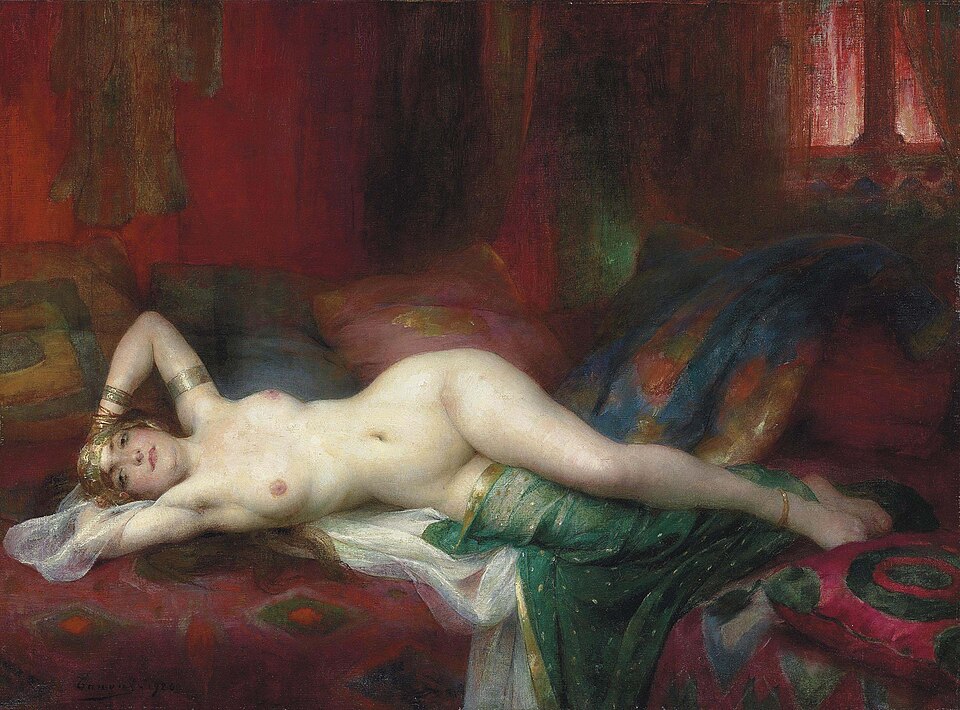

Throughout the 19th century, Orientalism became a popular theme in European salons and exhibitions. As the French and British empires expanded their influence in the East, curiosity about Islamic and Middle Eastern culture grew. Artists took advantage of this trend, crafting intricate scenes that combined the decorative with the alluring. The odalisque remained a central figure in these compositions, often set within highly stylized interiors.

One of the most renowned painters in this vein was Jean-Léon Gérôme, born in 1824. Gérôme studied under Paul Delaroche and developed a highly finished, polished style. His paintings of bathhouses, palace interiors, and reclining women were widely praised for their detail and realism. Gérôme was known for his meticulous research, though his works still leaned toward romantic idealization. He brought academic weight to Orientalist painting.

Gérôme, Renoir, and the Decorative Appeal

While Gérôme pursued realism, Pierre-Auguste Renoir offered a more impressionistic take on the odalisque. Renoir, born in 1841, painted many reclining nudes in lush surroundings, combining soft light with warm color. His models often rest on sofas or cushions, surrounded by patterned drapes or exotic prints. Though less overtly Eastern, these settings drew from the same decorative traditions seen in Orientalist art.

The odalisque had become a decorative motif—an excuse for artists to explore flesh, fabric, and form in elegant harmony. Paintings from this period often featured:

- Plush divans, cushions, and drapery

- Exotic-looking objects like hookahs or vases

- Jewels, veils, and richly textured fabrics

- Reclining poses suggesting comfort and luxury

Rather than focusing on narrative, these images emphasized sensual delight and compositional balance. The odalisque was no longer a figure with a story—it was a visual centerpiece that blended classical ideals with the aesthetics of leisure.

Picasso and the Cubist Transformation

Pablo Picasso, born October 25, 1881, in Málaga, Spain, was constantly reinterpreting the themes of past masters. By the mid-20th century, the odalisque had become a well-worn subject in Western painting. Picasso saw in it an opportunity not only to honor earlier artists but also to dismantle and rebuild the form in his own language. Between late 1954 and early 1955, Picasso created a series of 15 paintings titled “Les Femmes d’Alger,” directly inspired by Delacroix’s 1834 masterpiece.

Each version in the series explored a different configuration of color, shape, and mood, blending Cubist fragmentation with bold, simplified forms. The project began shortly after the death of Picasso’s friend Henri Matisse, who himself had painted many odalisques. Picasso saw the series as both homage and competition—a way to rival Delacroix and Matisse simultaneously. It was a dialogue across centuries.

“Les Femmes d’Alger” as Homage and Innovation

In these works, Picasso’s odalisques are no longer dreamy or remote. Their bodies are angular, abstracted, and sometimes aggressively stylized. The interiors are disjointed, flattened, and fractured. Rather than suggesting luxury or repose, the compositions vibrate with tension and invention. The reclining nude has become a formal experiment.

“Les Femmes d’Alger, Version O,” completed in 1955, would go on to break records at auction decades later. Sold in 2015 for over $179 million, it remains one of the most expensive paintings ever sold. The series as a whole is now seen as a milestone in late Picasso’s career. His engagement with the odalisque theme proved that even in the modern age, the form retained artistic vitality—not as a symbol of the exotic, but as a structure for reinvention.

The Odalisque in 20th-Century Western Art

As the 20th century progressed, artists continued to explore the reclining female figure, often returning to the odalisque theme for its formal possibilities. The setting and symbolism changed, but the pose remained. No longer bound by Orientalist fantasy, painters reinterpreted the odalisque as a timeless studio motif. The female figure, reclining in repose, served as a study in light, color, and composition.

One of the most notable modern interpreters of the odalisque was Henri Matisse, born in 1869. He painted dozens of odalisques, especially during the 1920s and 1930s, using models in patterned robes, seated against bright textiles and North African furnishings. Matisse did visit Morocco in 1912 and 1913, and the visual impressions stayed with him. But his interest lay less in cultural commentary than in rhythmic design, vivid color, and decorative harmony.

From Decorative Motif to Modern Classic

Other artists, such as Amedeo Modigliani and Tamara de Lempicka, also drew on the odalisque tradition, updating it with Art Deco aesthetics or Expressionist linework. The theme remained popular in sculpture, printmaking, and photography as well. Whether framed in an Orientalist interior or an abstract setting, the pose conveyed calm, introspection, and sensuality. It proved endlessly adaptable across styles.

In museums, collectors continued to value odalisque-themed works for their beauty and art-historical lineage. Paintings by Ingres, Delacroix, Gérôme, and Matisse found homes in national collections, where they were studied and admired not for political meaning but for mastery of form. The odalisque remained a figure of interest—an enduring subject in the conversation between artist and muse.

By mid-century, the odalisque had become more than a trope. It was a classical format—like the still life or the portrait—that artists could revisit, challenge, or celebrate. From its misunderstood origins to its modern interpretations, the odalisque evolved into a visual theme that transcended its initial context. It offered an enduring structure upon which beauty, design, and imagination could be explored.

The Timeless Appeal of the Odalisque

The odalisque figure has never truly vanished from the art world. Even today, it remains a favorite pose in figure drawing classes, museum exhibits, and private collections. The composition—a reclining female form, half-turned toward the viewer—offers artists a way to study light across surfaces and movement within stillness. It’s a theme as old as ancient Greece, yet still fertile ground for modern creativity.

Beyond painting, the odalisque shape appears in contemporary photography, interior design, and fashion editorials. Some artists choose to echo the classical odalisque directly, using similar furniture and fabrics. Others take inspiration only from the pose and use it in abstract settings. The figure continues to appeal not only for its beauty but for its formal balance and compositional clarity.

Why Artists Still Return to the Reclining Figure

Throughout centuries, the reclining nude has remained a cornerstone of Western art, and the odalisque is its most elegant variant. The curve of the body, the angle of the limbs, and the interplay of skin and fabric create a natural harmony. Whether depicted in rich surroundings or minimalist space, the odalisque invites quiet observation and reverence for form.

Today, the odalisque can be found in many of the world’s top museums, from the Louvre to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Students continue to copy these works as part of their training, and art lovers admire them for their poise and composition. The odalisque survives not as a political symbol, but as a study in repose, a celebration of form, and a reminder of painting’s long tradition of beauty and structure.

Key Takeaways

- The word “odalisque” originally referred to a servant in the Ottoman harem.

- Ingres’s 1814 La Grande Odalisque helped define the genre in Western art.

- Delacroix brought color and atmosphere to the odalisque through Romanticism.

- 19th-century painters like Gérôme and Renoir turned the theme into visual indulgence.

- Picasso and Matisse reimagined the odalisque in modernist and decorative ways.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What does the term “odalisque” mean in art?

It refers to a reclining female figure, often depicted in exotic or classical surroundings. - Who painted the most famous odalisque?

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted La Grande Odalisque in 1814. - Is the odalisque a real historical figure?

The original term described a servant in the Ottoman Empire, not an artistic muse. - Why did artists use Eastern themes in these paintings?

They were inspired by travel writing, imagination, and the visual richness of exotic settings. - Do modern artists still paint odalisques?

Yes, many artists reinterpret the pose as a timeless study in form and beauty.