In a world racing toward the future, the Gullah people stand firm in their past. Along the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, this unique African-American community has preserved not only its language and traditions but also a vibrant and deeply spiritual artistic heritage. Gullah art isn’t confined to galleries—it’s stitched into quilts, woven into baskets, painted in vivid strokes, and spoken through ancestral stories. It is living testimony to faith, perseverance, and cultural memory.

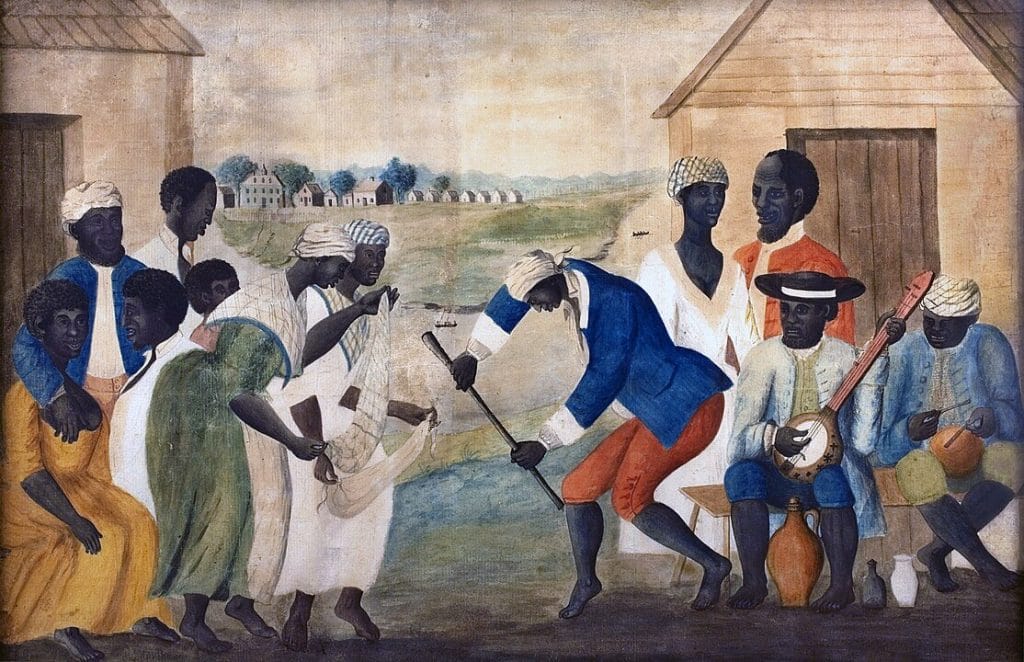

The Gullah are descendants of enslaved Africans who were brought to the American South during the 18th and 19th centuries, primarily to work the rice and cotton plantations of the coastal Lowcountry. Isolated on barrier islands and deeply rooted in West African customs, they retained more of their African linguistic, cultural, and artistic identity than any other African-American group in the United States. Their distinctive Creole language, spiritual expressions, and folkways have endured for generations, shaped by hardship, hope, and faith.

What sets Gullah art apart is its foundation in communal life and its deep spiritual core. Art isn’t created for vanity or applause—it is born of necessity and meaning. A sweetgrass basket isn’t just beautiful; it’s a practical tool and a cultural heirloom. A quilt is not merely a bed covering but a family story stitched in code. Paintings of daily life or spiritual rituals are rich in color and conviction, often expressing unspoken truths with clarity and boldness.

Throughout this article, we’ll explore the many layers of Gullah artistic expression: the craftsmanship of sweetgrass baskets, the storytelling in vibrant paintings, the powerful oral traditions that carry both faith and folklore. We’ll examine the essential role of women in preserving and teaching these traditions, the relationship between the land and Gullah creativity, and the challenges and triumphs of preserving a culture in the modern age. Through it all, one theme rings true: Gullah art is a song of survival—composed in the language of family, faith, and freedom.

A People Set Apart: The Historical Roots of Gullah Identity

The story of Gullah art begins long before the first brushstroke or woven basket. It begins in the rice fields of West Africa, in the villages along the Gambia, Sierra Leone, and Angola coasts. The people brought to the Sea Islands during the transatlantic slave trade came from cultures already rich in textile design, basketry, oral history, and agricultural knowledge. When they were enslaved and brought to the American South, they carried these skills and stories with them—hidden in memory, passed down in song and rhythm, guarded in silence.

What makes the Gullah unique among African Americans is the degree to which they retained these traditions. Because of the Sea Islands’ geographic isolation and the semi-tropical environment, plantation owners often left the islands in the heat of summer, leaving the enslaved to govern themselves to a greater extent than on mainland plantations. This gave the Gullah people a rare opportunity to preserve their language, religious customs, cooking methods, and craft techniques with little interference.

Christianity soon became a central pillar of Gullah life. Enslaved people found powerful resonance in the stories of Moses, Exodus, and spiritual deliverance. But their faith was not a carbon copy of European Christianity. Instead, it was infused with African rhythms, storytelling methods, and symbolism. Worship was often done in “praise houses”—small, wooden buildings where singing, dancing, and prayer blended into something wholly original. This spiritual tradition laid the foundation for Gullah art: expressive, symbolic, rooted in Scripture, and tied deeply to the community’s lived experience.

Family and oral history also anchored Gullah identity. In a world that often tried to erase their past, the Gullah remembered. They passed on stories, proverbs, and sayings in their unique Creole language—a blend of English and West African grammar and vocabulary. These stories often held practical wisdom, moral lessons, or biblical truths. The art that grew out of this culture was not separate from daily life—it was daily life. Art was memory made visible, purpose made beautiful.

In this way, the Gullah emerged as a people set apart—not by choice, but by history and providence. Their art reflects the tension of survival and the triumph of endurance. It speaks of a people who refused to let go of their roots, even when uprooted. And that, more than anything, is what gives Gullah art its lasting power and unmistakable voice.

Sweetgrass Basket Weaving: A Legacy of Patience and Prayer

One of the most cherished and visible expressions of Gullah craftsmanship is the sweetgrass basket. Intricately coiled, woven by hand, and passed down through generations, these baskets are both functional and deeply symbolic. To watch a Gullah basketmaker work is to witness centuries of history spun in every stitch, a living link between Africa and America.

The origins of sweetgrass basketry trace back to West Africa, where similar coiled techniques were used to create rice fanners and storage baskets. In the Lowcountry, these traditions were adapted using local materials like sweetgrass, palmetto fronds, bulrush, and pine needles. The resulting baskets were essential for everyday life on the plantation: sorting grain, carrying goods, or holding food. Over time, they evolved into works of folk art—treasured not just for their utility, but for their craftsmanship and cultural resonance.

The process of making a sweetgrass basket is slow, intentional, and meditative. It begins with gathering the right materials, often by hand and with care for the land. Sweetgrass must be harvested at dawn or dusk to preserve its fragrance and flexibility. The palmetto strips that bind the coils are stripped and soaked, then twisted and stitched using a bone needle or nail. The patterns are passed down orally and visually, not through written instructions. Each basket is unique, shaped by the maker’s rhythm and experience.

Traditionally, women have been the primary keepers of this art form. Mothers teach daughters, grandmothers guide little ones, and the craft becomes a bridge between generations. The act of weaving is often accompanied by prayer or quiet reflection—a sacred act, not just a skill. For many Gullah women, basketmaking is not only a source of income but also a spiritual practice, a moment to connect with God, their ancestors, and the natural world.

In recent decades, sweetgrass baskets have gained national attention. Featured in museums and sold in Charleston’s historic markets, they have become emblems of African-American folk heritage. But this recognition brings its own challenges. As demand rises, basketmakers must decide how much to produce, how much to charge, and how to protect their intellectual and spiritual property. Some have trademarked their designs or formed cooperatives to maintain quality and authenticity. Others worry that mass production and tourist expectations threaten the soul of the craft.

Still, the sweetgrass basket endures—humble, beautiful, and resilient. It is more than a souvenir. It is a sermon in straw, a memory made by hand, and a symbol of what it means to hold fast to tradition in a changing world.

Painting the Gullah World: Faith, Color, and Everyday Life

If sweetgrass baskets are the quiet heartbeat of Gullah art, then Gullah painting is its song—vivid, rhythmic, and full of life. Through bold color and expressive imagery, Gullah artists depict their community’s stories, struggles, and spiritual strength. These paintings are more than decorative—they are testimonies, painted prayers, and visual sermons capturing moments of both history and hope.

Perhaps the most well-known Gullah painter is Jonathan Green, a South Carolina native whose works have brought national attention to Lowcountry culture. His paintings burst with vibrant hues, wide-brimmed hats, dancing figures, and scenes of church services, family gatherings, and coastal life. Green’s art blends celebration with seriousness. Beneath the joyful brushstrokes lies a deep reverence for tradition, dignity, and moral order. His subjects are not idealized fantasies—they are strong, graceful depictions of everyday Gullah people living in faith and fellowship.

Other Gullah artists like Sonja Griffin Evans and Diane Britton Dunham also use their art to spotlight family, faith, and cultural pride. Their canvases often include symbolic elements: the rising sun for renewal, birds for freedom, or open Bibles for guidance. Churches feature prominently, as do scenes of worship, baptism, and spiritual revival. Through these images, artists remind both their own people and outside viewers that the center of Gullah life is the church—not only as a building, but as a community rooted in Scripture and service.

What makes Gullah painting unique isn’t just the subject matter—it’s the approach. There is no abstraction here, no highbrow detachment. The art is accessible and emotional. It tells stories in ways that echo the oral traditions of old. A painting might show a grandmother quilting, a father casting a net into the sea, or children dancing at a wedding—all with enough detail to make the viewer feel like part of the moment. Every brushstroke serves a purpose: to honor the past, reflect the present, and inspire the future.

As Gullah painting gains more visibility in galleries and cultural events, many artists remain committed to their roots. They reject trends that distance art from morality or remove it from its community context. For them, painting is not a personal statement—it’s a cultural duty. It is a way to preserve what their ancestors built, to speak truth to a world that often forgets, and to glorify the God who brought them through slavery, hardship, and change.

Storytelling and Spiritual Expression

The Gullah people are, first and foremost, storytellers. Long before baskets were sold or paintings hung in galleries, Gullah culture was carried in the spoken word. Around fire pits, in praise houses, and across porches at sunset, stories were told—not just for entertainment, but for survival, instruction, and worship. Today, that storytelling tradition remains one of the most enduring and vital forms of Gullah art.

At the heart of Gullah storytelling is a mix of African oral tradition and biblical truth. Folktales like those of Br’er Rabbit—the clever trickster who outsmarts stronger foes—carry African roots while teaching moral lessons. These tales, passed from elders to children, reinforce values like wisdom, humility, and perseverance. They also serve as coded narratives of survival in a world that often sought to silence and control.

Storytelling in the Gullah community isn’t limited to fables. Testimonies, sermons, and “shout” songs—where biblical themes are sung and danced—are all part of the expressive tapestry. Praise houses, small wooden structures for worship, became spiritual centers where stories of Moses and deliverance took on new meaning. The rhythm of speech, the cadence of preaching, and the communal call-and-response reflect both African heritage and deep Christian conviction. In these moments, art and faith are inseparable.

The elders are the keepers of these stories, and their role is sacred. A grandmother’s story about “haints” (spirits), a grandfather’s tale about farming in the marshes, or a preacher’s parable from the pulpit—each becomes a vessel for preserving memory and teaching right living. Gullah storytelling is less about performance and more about connection. It binds generations and reminds the young who they are, whose they are, and where they came from.

Today, Gullah storytelling is celebrated at festivals, churches, and schools. Professional storytellers like Aunt Pearlie Sue (Anita Singleton-Prather) carry on the tradition with humor, reverence, and educational purpose. But in truth, every Gullah family has its own keepers of the word—individuals who know that truth wrapped in a story is more powerful than truth shouted on a billboard.

In a fast-moving world that often prizes noise over meaning, the Gullah storytelling tradition stands as a quiet force—a reminder that words can heal, teach, and praise when spoken with love, memory, and conviction.

Gullah Quilting and Textile Traditions

Quilting holds a special place in Gullah life—not just as a domestic necessity, but as a rich medium for storytelling, family remembrance, and spiritual symbolism. In the Gullah tradition, a quilt is far more than layers of fabric stitched together for warmth. It is a tapestry of faith, survival, and heritage, often created by hands guided by both memory and prayer.

The roots of Gullah quilting stretch deep into African textile traditions and Southern folk art. Enslaved women on plantations were tasked with making quilts for their enslavers, often out of cast-off materials. Yet, from these remnants, they fashioned quilts of remarkable beauty and complexity. After Emancipation, quilting continued in the Gullah community as a key part of family life—both functional and expressive. Each quilt told a story, preserved a lineage, or marked a sacred occasion such as a marriage, a birth, or a death.

Unlike the more polished and symmetrical patterns common in Anglo-American quilts, Gullah quilts often feature improvisational designs, bright contrasting colors, and symbolism drawn from nature and Scripture. Some include crosses, stars, or roads representing journeys—both physical and spiritual. Others are “story quilts” where each square or patch serves as a scene, representing a person, an event, or a lesson. In this way, Gullah quilting overlaps with oral tradition, turning words into visual motifs.

The process of quilting is communal. Women gather together—sometimes around kitchen tables, sometimes under live oak trees—to stitch, teach, and share. It’s during these gatherings that children learn not only the craft but the values that come with it: patience, diligence, humility, and care. Stories are told as hands move, and every finished quilt carries not just thread, but the fingerprints of many hearts working in harmony.

In modern times, Gullah quilts have gained recognition in museums, church displays, and art shows. But within the community, their value remains spiritual and personal. They are heirlooms and testimonies. They are stitched prayers. And as long as Gullah grandmothers are still quilting, the story of the people will continue to be written—one square at a time.

Faith, Family, and the Role of Women in Gullah Artistic Life

In Gullah culture, women are the backbone—not only of the family and the church, but of artistic tradition. They are the storytellers, the quilters, the basket weavers, and the keepers of songs. Through their hands, hearts, and voices, Gullah women have preserved a way of life against centuries of hardship, change, and outside pressure. Their artistry is not loud, but it is lasting.

From a young age, Gullah girls are taught by their mothers and grandmothers to create with intention. Whether it’s weaving a basket, stitching a quilt, or cooking a family dish, the act of making is always tied to something deeper—faith in God, love for family, and respect for ancestors. These aren’t hobbies; they’re responsibilities. Each skill passed down is a form of moral instruction and cultural preservation.

The church, often led and nurtured by women behind the scenes, is the heart of this artistic expression. Women lead prayer circles, sing in choirs, organize church dinners, and craft items for fundraisers. Their contributions are not flashy or celebrated in the world’s eyes, but within the Gullah community, they are seen for what they are: sacred acts of service. Art, when done by Gullah women, is an extension of their role as nurturers, protectors, and spiritual leaders in the home.

Many Gullah women also serve as unofficial historians. They remember the stories of great-grandmothers who picked cotton and mothers who walked miles to attend church. They can tell you where a certain quilting pattern came from or what a particular sweetgrass design means. This oral legacy, woven into every piece they create, ensures that Gullah identity doesn’t just survive—it thrives.

In recent years, Gullah women have begun to receive more recognition for their artistic and cultural roles. Documentaries, exhibits, and festivals have started spotlighting these matriarchs, often placing their work alongside that of more widely known artists. But for many of them, the praise is secondary. Their joy lies in teaching a granddaughter how to stitch a corner properly, or showing a neighbor’s child how to tie a palmetto strip just right.

Through quiet strength and enduring faith, Gullah women have not only kept their traditions alive—they’ve made them flourish. They are the silent architects of a culture built on faith, family, and the belief that beauty serves best when it flows from love.

Gullah Art in the Modern World: Fame, Faith, and the Fight for Preservation

As Gullah art continues to gain recognition outside its traditional boundaries, the community finds itself at a crossroads. On one hand, exhibitions, festivals, and collectors are helping to bring long-overdue respect to Gullah culture. On the other, the pressures of commercialization, tourism, and cultural appropriation threaten to dilute its meaning. The challenge is clear: how do you share your story without letting others rewrite it?

Gullah art began to attract national attention in the late 20th century as folk art movements gained popularity and scholars began to study African-American cultural traditions more seriously. Painters like Jonathan Green found audiences beyond the Sea Islands. Basket makers were invited to Smithsonian events. Quilts once made for warmth and weddings were now framed and hung in galleries. Suddenly, what had been personal became public—and the Gullah were asked to perform their heritage.

Many artists and elders welcome the opportunity to share their faith and culture, but they insist on doing so on their terms. The most respected Gullah creators maintain that art must remain connected to its original purpose: storytelling, family, and glorifying God. They resist the temptation to make items simply for what will sell. A basket that mimics Gullah form but is made in a factory overseas may look the part, but it has no spirit. It is, in essence, a lie.

Tourism brings a similar double-edged sword. Charleston’s market is filled with sweetgrass baskets and paintings labeled “Gullah,” yet not all of them are authentic. Some vendors sell mass-produced items, exploiting the culture for profit. This concerns many within the community who fear that Gullah identity is being turned into a brand—stripped of its roots in faith, family, and history.

At the same time, Gullah activists and artists are working hard to preserve what matters. Organizations like the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission and the Penn Center on St. Helena Island help support authentic education, documentation, and community programs. Younger artists are learning from elders while using modern tools—like documentaries, online galleries, and school residencies—to pass the torch.

For the Gullah, success is not measured by fame or sales, but by faithfulness. Will the story continue? Will the children know the meaning of the songs, the stitches, the stories? As long as the answer is yes, Gullah art will remain what it has always been: not a commodity, but a covenant—between past and future, earth and spirit.

The Land and the Sea: Nature as Muse and Meaning

The landscape of the Sea Islands isn’t just a backdrop to Gullah life—it’s a central character in the story. The marshes, rivers, palmetto groves, and sandy shores of coastal South Carolina and Georgia have shaped the Gullah experience for generations. It’s from this land that their food grows, their stories rise, and their art flows. Nature, in all its beauty and hardship, is both muse and metaphor.

Sweetgrass baskets, for instance, are only possible because of the unique coastal vegetation. The grass, once found in abundance, now requires intentional stewardship to preserve. Families travel long distances to harvest it, often revisiting the same secret spots their ancestors once used. The act of gathering is as important as the weaving—it connects the artist to the land, the past, and the Creator.

Painters often depict this natural world with reverence. Scenes of shrimping boats, oyster beds, and live oak trees are common themes. These aren’t just pretty pictures; they reflect a worldview where man and earth are meant to live in harmony. The tides and seasons are part of God’s order. The land is not merely used—it is honored. To live in balance with creation is to live rightly.

Gullah stories, too, are filled with natural imagery. Water, especially, holds deep meaning. It represents both danger and deliverance—the middle passage from Africa, the rivers that carried freedom-seekers, the baptismal streams where souls were claimed for Christ. Storms symbolize trial and testing, while fertile land stands for blessing and endurance. Nature becomes a divine language, speaking truths too profound for plain words.

But this sacred relationship is under threat. Development, rising sea levels, and gentrification endanger not just Gullah land but Gullah life itself. Marshes are paved, historic homes are sold, and ancestral burial grounds are threatened. Many artists and elders are now using their platforms to advocate for land rights and environmental preservation—not from a political standpoint, but from a spiritual and cultural one. Losing the land, to them, would be like losing a chapter of the Bible.

Art becomes a way to fight back—not with anger, but with clarity and beauty. Every painting of a shrimp boat, every story about a flood survived, every basket woven from the earth itself says the same thing: “This place matters. We are still here. And we are not finished yet.”

Looking Ahead: The Next Generation of Gullah Creators

The story of Gullah art is far from over. As one generation fades, another rises—often with one foot in the old world and one in the new. The challenge for today’s young Gullah creators is not only to honor the traditions of their elders but to carry them forward in a changing world. It’s a challenge they are meeting with quiet strength and purposeful innovation.

In families across the Lowcountry, grandparents still teach children how to weave, paint, and tell stories. Young girls sit beside their grandmothers, learning the rhythm of the basket stitch. Boys fish with their fathers and hear tales that stretch back before the Civil War. These are not just family moments—they are acts of cultural preservation. They are how the torch is passed, not in speeches, but in everyday acts of faithfulness.

Meanwhile, schools, churches, and cultural centers are stepping up to support this intergenerational mission. Programs teach sweetgrass basketry, Gullah language basics, and oral storytelling techniques. Festivals celebrate Gullah art with workshops and performances, giving young people a stage to both learn and lead. Technology—even when used carefully—is becoming a tool to document stories, share music, and connect isolated communities across state lines.

Young Gullah artists are also expanding the definition of what their art can be. Some are using digital media to tell old stories in new ways. Others blend hip-hop with spirituals, or traditional painting with social commentary. What remains constant is the anchor in heritage. These creators are not abandoning their roots—they are growing from them, like palmetto trees reaching toward the sun.

Still, the road ahead isn’t easy. The pressures of modern life, cultural assimilation, and economic instability can lure young people away from traditional roles. That’s why mentorship is so important. When elders teach youth not just the “how” but the “why,” the legacy is preserved. Because the real power of Gullah art lies not in the object, but in the spirit behind it—a spirit that says: We remember. We endure. We create.

In that way, the next chapter of Gullah art is already being written—not by scholars or collectors, but by children sitting beside their elders, hands moving, hearts listening, and stories being stitched into the future.

Key Takeaways

- Gullah art is deeply rooted in African heritage, Christian faith, and Southern tradition.

- Sweetgrass basketry, quilting, storytelling, and painting serve both practical and spiritual purposes.

- Women play a central role in preserving and passing down Gullah artistic traditions.

- While Gullah culture gains recognition, challenges remain in resisting commercialization and cultural erasure.

- The next generation is blending old forms with new tools, keeping the legacy alive with reverence and resilience.

FAQs

- Who are the Gullah people?

The Gullah are descendants of enslaved Africans who settled on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, preserving African traditions in language, faith, and art. - What types of art do the Gullah create?

Their artistic expressions include sweetgrass basketry, quilting, painting, storytelling, spiritual songs, and oral histories. - Why is faith so central to Gullah art?

Christian faith provides the moral and emotional foundation for Gullah culture, deeply influencing its artistic forms and themes. - Are young people continuing Gullah traditions?

Yes, through family teaching, school programs, and festivals, young Gullah are learning and expanding upon traditional arts. - Is Gullah art at risk of being commercialized?

Yes, increased tourism and interest have led to concerns about authenticity, prompting efforts to protect and properly represent the culture.