Before pills came in blister packs and prescriptions were filled by machines, medicine was the realm of leaves, roots, and bark. At the heart of this ancient world stood the apothecaries—early pharmacists who relied on nature’s offerings to treat everything from fevers to fractures. Yet beyond their practical role, apothecaries cultivated a lesser-known legacy: the artful depiction of medicinal plants. This practice, which blended observation with careful draftsmanship, laid the groundwork for botanical illustration.

Botanical drawings were essential before standardized texts and modern printing. Plants often had different names in different regions, and visual reference helped clarify what was safe or toxic. With diseases spreading rapidly in the pre-modern world, accuracy mattered—misidentification could be fatal. That’s why the apothecary’s illustrated manuals became such treasured guides, passed from master to apprentice with reverence.

These works were not merely scientific—they were deeply beautiful. The detailed contours of a leaf, the precise shape of a flower’s petals, or the twisted lines of a root system were all drawn with care and clarity. This devotion to realism elevated these manuals from tools to works of art. They also preserved knowledge at a time when oral tradition was still a key part of healing.

In this article, we trace the history of this remarkable tradition—from ancient Greece to Enlightenment France. We’ll meet pioneering artists, resilient women, and forgotten healers who turned medicinal plants into artistic legacy. And we’ll see how, in preserving nature’s remedies, they also preserved beauty.

Roots in Antiquity – Herbal Knowledge Before the Renaissance

Long before the Renaissance reawakened scientific curiosity in Europe, civilizations across the Mediterranean and Near East were compiling detailed records of the healing power of plants. Egyptian papyri, such as the Ebers Papyrus from around 1550 BC, listed hundreds of remedies drawn from native flora. Meanwhile, Indian Ayurvedic and Chinese medicinal traditions were independently developing similar herbal systems. These ancient texts may not have contained illustrations, but they laid the foundation for visual documentation that would flourish centuries later.

One of the earliest known efforts to pair text with image in the field of medicinal plants came from Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician born around AD 40 in Anazarbus (modern-day Turkey). Serving as a surgeon in the Roman army, Dioscorides had access to a wide variety of plant life across the empire. His most famous work, De Materia Medica, written around AD 60, was a five-volume treatise detailing over 600 plants and their medicinal uses. It remained the central pharmacological reference in Europe for more than 1,500 years.

Dioscorides and De Materia Medica

What made De Materia Medica revolutionary was not only its exhaustive content but its visual ambition. Surviving manuscript copies—such as the Vienna Dioscurides, created in AD 512—include finely painted images that attempt to replicate plant features faithfully. These early illustrations were more symbolic than realistic, but they served a vital purpose in visually differentiating species.

Dioscorides’ influence extended into Islamic medicine during the Middle Ages, where translations and adaptations were made in Arabic, Persian, and Syriac. These translations preserved both the textual content and often added their own stylistic illustrations. His work provided a continuous thread of herbal knowledge from antiquity into early modern Europe, helping guide the development of apothecary practice in monasteries and universities.

The Golden Age of Herbals – 15th to 17th Century Flourish

The invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century ignited a boom in illustrated botanical books known as herbals. These texts became more affordable, accessible, and standardized, leading to a rapid spread of botanical knowledge throughout Europe. With advances in woodcut printing, apothecaries could now consult illustrated guides that were far more accurate than their medieval predecessors. The growing demand for plant-based remedies, especially after the Black Death, only increased the value of these publications.

Among the most influential figures of this period was Leonhart Fuchs, born in 1501 in Wemding, Germany. Fuchs studied medicine at the University of Ingolstadt and later became a professor at the University of Tübingen. In 1542, he published De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes (“Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants”), one of the most detailed and lavishly illustrated herbals of its time. The book contained over 500 plant descriptions and illustrations based on live specimens—a revolutionary method at the time.

Leonhart Fuchs and the German Herbal Tradition

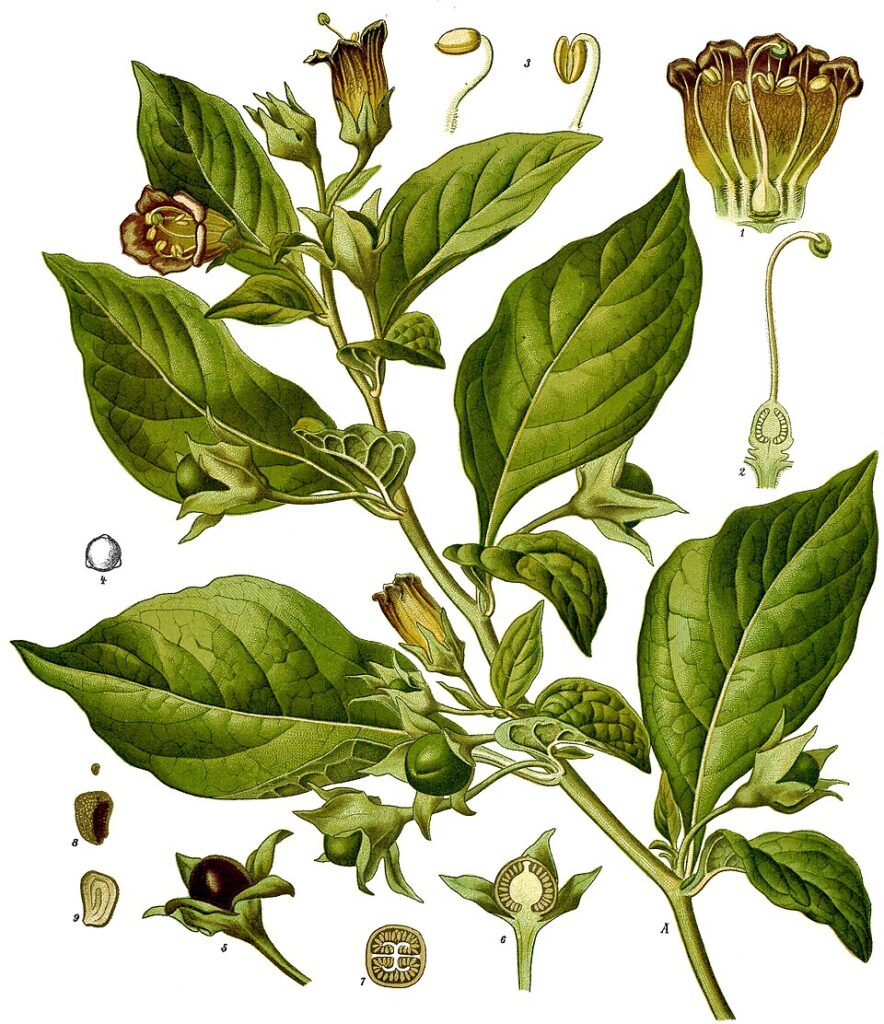

Fuchs collaborated with skilled artists such as Albrecht Meyer (illustrator), Heinrich Füllmaurer (engraver), and Veit Rudolf Speckle (colorist), producing illustrations that were not only botanically accurate but artistically elegant. Each image was drawn from live plants cultivated in Fuchs’ own garden. Unlike earlier stylized depictions, these illustrations showed plants with roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and sometimes seeds—every part necessary for accurate identification.

Fuchs’s contribution to both medicine and art extended far beyond his lifetime. His name is still remembered today in the plant genus Fuchsia, named in his honor. His approach to integrating scientific rigor with artistic detail influenced generations of apothecaries and naturalists, including later herbalists in England and the Netherlands. His work helped set a new European standard for both accuracy and beauty in herbal texts.

Apothecaries as Artists – The Visual Language of Healing

In a time when photography did not exist and Latin was not universally understood, visual art became the universal language of science. For apothecaries, illustrations weren’t optional—they were essential. A misread label or an ambiguous plant name could mean disaster. That’s why precision in drawing became an important part of training in apothecary schools and guilds, particularly in cities like Florence, Paris, and Nuremberg.

Botanical illustrations had to be both attractive and accurate. They were often created through woodcut or copperplate engravings and then hand-colored, especially in high-quality herbals. Each part of the plant—stem, leaf, root, flower, fruit—was shown in detail, often in full bloom. Many of these drawings were produced by professional artists working closely with apothecaries or scholars, ensuring scientific credibility.

Techniques and Tools of Botanical Illustration

Artists used magnifying glasses, plant presses, and inks derived from natural materials to depict plants as closely as possible to life. They often drew from fresh specimens to capture correct coloration and shape. Common materials included parchment, handmade paper, and mineral-based pigments that retained their vibrancy over centuries. The work was slow, methodical, and demanded exceptional discipline.

These illustrations were often organized into bound volumes or mounted in shops for apprentice study. The drawings became not only medical references but teaching tools. Their importance was underscored by guild requirements across Europe that mandated herbal knowledge—and often visual proficiency—for practicing apothecaries. The marriage of science and art was not merely functional; it was institutionalized.

Women in the Herb Garden – Unsung Contributors to Apothecary Art

Though often left out of the official histories, women played a significant role in herbal medicine and its illustration. In domestic settings and convents, women were often the first line of healing. They prepared tinctures, catalogued plant lore, and maintained herbal gardens. However, it was rare for women to gain recognition in the male-dominated publishing world—until Elizabeth Blackwell.

Elizabeth Blackwell was born around 1707 in Aberdeen, Scotland. She married Alexander Blackwell, a physician and printer, but his poor business dealings landed him in debtor’s prison. To support her family, Elizabeth embarked on a daunting project: writing and illustrating her own herbal. The result was A Curious Herbal, published between 1737 and 1739, a landmark not only in botanical science but in women’s history.

Elizabeth Blackwell and A Curious Herbal

Over the course of two years, Elizabeth produced over 500 hand-colored plates. She drew, engraved, and colored each plant herself, based on live specimens grown at the Chelsea Physic Garden in London. Her husband, still in prison, provided Latin names and medical notes for the descriptions. The work was published in weekly installments and gained approval from the Royal College of Physicians.

Elizabeth’s herbal was groundbreaking in its inclusion of New World plants such as tobacco and cacao, reflecting the global reach of 18th-century apothecaries. Her contributions were largely forgotten after her death in 1758, but modern scholarship has begun to recognize her as a pioneering figure in both art and medicine. Her legacy is a powerful reminder of the overlooked women in scientific history.

Apothecaries, Trade, and Empire – Global Plants in Local Pharmacies

As European empires expanded across Asia, Africa, and the Americas, so too did their access to foreign plants. Apothecaries were among the first to benefit from this growing botanical exchange, gaining access to spices, roots, and herbs unknown in Europe. This influx transformed both medicine and art, as herbal manuals began to include species from every continent. The result was a more diverse and visually rich body of work.

Illustrations played a crucial role in documenting and disseminating this knowledge. Unlike native plants, foreign specimens often had no known names in European languages, making visual identification even more critical. Drawings from explorers, missionaries, and colonial apothecaries began to appear in herbals and scientific compendiums. These new additions brought exotic imagery and expanded the artistic vocabulary of botanical illustration.

The Influence of Colonial Botany

Institutions like Kew Gardens in England and the Hortus Botanicus in Leiden, Netherlands, became global repositories for plant knowledge. Supported by trading companies like the Dutch East India Company and British East India Company, these gardens collected thousands of samples from colonies. Each plant was catalogued, illustrated, and classified—often without credit to the indigenous communities that had long used them medicinally.

Apothecaries across Europe began incorporating these new ingredients into their pharmacopeias. Plants such as cinchona (for malaria), sassafras (as a stimulant), and ipecac (to induce vomiting) entered mainstream use. Yet while this broadened medical knowledge, it also reflected the darker realities of colonial exploitation. The apothecary’s art became a mirror of empire—beautiful, global, and morally complicated.

From Science to Sentiment – The Shift to Decorative Botanical Art

As modern chemistry began to replace traditional herbal remedies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the role of the apothecary began to fade. But the art they had nurtured did not disappear. Instead, botanical illustration took on a new role as a decorative and scientific pursuit for the educated elite. Wealthy patrons commissioned plant illustrations not for healing, but for collecting, learning, and admiring nature’s elegance.

One of the most celebrated figures in this transition was Pierre-Joseph Redouté, born in 1759 in Saint-Hubert, Belgium. Redouté trained as a painter but found his true calling in natural history. After moving to Paris, he became official court artist to Empress Joséphine Bonaparte. There, he created Les Liliacées and Les Roses, two volumes that remain high-water marks in botanical art.

Redouté and the Romanticization of Plants

Redouté pioneered stipple engraving techniques that gave his illustrations a soft, lifelike quality unmatched by earlier works. His roses shimmered with delicate color transitions, and his lilies displayed structural precision. These were not merely scientific illustrations—they were celebrations of divine design in nature. Redouté’s art made plants fashionable among aristocrats and intellectuals alike.

His work marked a turning point: botanical illustration was no longer just about medical identification—it was about appreciation. As science grew more specialized, botanical art became increasingly separate from pharmacology. But its roots in the apothecary tradition remained visible in every carefully inked stem and delicately shaded petal.

Preservation and Revival – Why Apothecary Art Still Matters

Though apothecaries are mostly gone, their illustrated legacies live on in libraries, museums, and digital archives. Institutions like the British Library, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Wellcome Collection have preserved countless herbals and botanical drawings. These works are now being digitized and made freely available to researchers and the public, helping revive interest in both historical medicine and artistic technique.

Modern artists and herbalists alike are rediscovering the value of these illustrations. Some use them as models for learning traditional drawing methods, while others incorporate them into modern wellness branding. In an age of mass production, the detailed, handmade quality of historical herbal art is finding new appreciation.

Digital Archives and Contemporary Rediscovery

Technology now allows high-resolution scans of centuries-old books to be viewed from anywhere in the world. Projects like the Biodiversity Heritage Library have made thousands of images searchable by plant name, artist, or region. For educators, historians, and plant enthusiasts, these digital archives offer a treasure trove of visual and scientific knowledge.

Today’s interest in natural remedies, organic lifestyles, and visual storytelling has brought apothecary art full circle. From social media aesthetics to homegrown wellness brands, the old drawings have new life. They continue to remind us that healing can be both a science and an art—and that both require close observation and care.

A Legacy Etched in Leaf and Ink

Botanical illustrations from the apothecary tradition are more than scientific records—they are works of devotion. Each drawing represents a moment where art and healing converged. Today, as we rediscover the value of nature in health and beauty, these illustrations offer more than history—they offer inspiration. Their legacy, inked into the pages of centuries, continues to bloom.

Key Takeaways

- Apothecaries used botanical illustrations as essential tools for plant identification and healing.

- Pedanius Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica remained influential for over 1,500 years.

- Leonhart Fuchs and Elizabeth Blackwell set new standards for illustrated herbals.

- European trade and empire expanded the apothecary’s palette with exotic plants.

- Botanical art today is preserved in archives and revived by modern artists.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Dioscorides and why is he important?

Dioscorides was a Greek physician whose work De Materia Medica became the cornerstone of herbal medicine for centuries. - How did apothecaries use illustrations?

They relied on accurate plant drawings to identify species, especially when plant names varied across regions. - Were women involved in early herbal illustration?

Yes. Elizabeth Blackwell is a prime example of a woman who created an entire illustrated herbal in the 18th century. - What role did colonialism play in apothecary art?

It expanded access to global plants but often appropriated indigenous knowledge without credit. - Why does apothecary art matter today?

It bridges science and art, preserving both plant knowledge and artistic heritage in a single form.