Stretching across eight countries and forming the backbone of central Europe, the Alps are more than a geographic feature—they are a civilization-shaping force. For thousands of years, these mountains have stood not as barriers, but as connectors, drawing together people, cultures, and ideas. Traders, pilgrims, soldiers, and artists have crossed these ranges with determination and ingenuity, leaving behind a visual legacy as layered and rugged as the mountains themselves. The Alps, far from being remote or peripheral, have played a central role in the shaping of European art.

The art history of the Alps is not defined by a single movement, empire, or school. It is instead a story of diverse yet interconnected traditions shaped by local materials, climate, political realities, and religious institutions. From ancient petroglyphs to Baroque altarpieces, from Gothic frescoes tucked into secluded valleys to high-modernist sculpture parks perched on Alpine ridges, this region has cultivated its own visual language—one that reflects both the grandeur of its setting and the industrious spirit of its inhabitants.

This story is fundamentally shaped by geography. The very nature of Alpine life—elevated terrain, harsh winters, strategic passes—has forged a distinctive approach to making and viewing art. Building a church in the Engadin or carving a sculpture in Tyrol required different skills and priorities than in the flatlands of Flanders or Tuscany. Materials had to be sourced locally: stone, wood, lime, and pigment, often quarried or harvested nearby. This created strong regional styles—whether in the crisp woodcarvings of Switzerland or the painted ceilings of Austrian pilgrimage churches.

Yet the Alps were never cut off. They were threaded by vital trade routes, most famously the Via Claudia Augusta and the Gotthard Pass, which connected northern Europe to the Italian peninsula. Along these arteries, artistic styles traveled with merchants and clergy. The result was a fusion of northern precision with southern expressiveness—a dialogue between the sacred austerity of the Romanesque and the humanism of the Renaissance, between the grandeur of the Baroque and the rustic charm of folk ornament.

Another key factor was the strength of local patronage. Alpine towns and villages, while smaller in scale than the capitals of empires, often supported skilled artisans and ambitious building projects. Monasteries, in particular, served as both spiritual centers and artistic patrons. Abbeys like St. Gallen, Einsiedeln, and Ottobeuren produced and preserved illuminated manuscripts, architectural innovations, and ecclesiastical art that rivaled anything found in Paris or Rome.

The Alpine regions also maintained strong traditions of vernacular art—wooden chalets adorned with painted panels, decorated ceramics, carved furniture, and practical items elevated by skilled hands into works of enduring beauty. While these objects were born of utility, they carry aesthetic values that reflect generations of regional pride and continuity. They tell a parallel story to the grand narratives of elite art—a story of families, seasons, rituals, and landscape.

From the 18th century onward, the Alps became a subject of fascination for artists outside the region. The dramatic landscapes, once feared as wild and desolate, were reimagined as sublime. Painters from across Europe traveled to sketch the Matterhorn or the Dolomites, adding Alpine peaks to the expanding vocabulary of Romanticism and national pride. At the same time, Alpine artists responded to these currents with their own interpretations—sometimes idealized, sometimes brutally real.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the Alps have seen continued artistic evolution. While retaining deep links to heritage and craft, the region has also embraced modernism, installation art, and new media. Art schools in cities like Salzburg and Lausanne have nurtured generations of artists who explore both tradition and innovation. Cultural festivals, biennials, and open-air sculpture parks now draw international audiences to mountain settings where creativity meets nature at high altitude.

To explore the art history of the Alps, then, is to travel through time and across borders. It is to see how people made beauty under challenging conditions, how they used art to express devotion, identity, and mastery, and how their work continues to resonate today. This is not a marginal story. It is central to understanding how regional traditions contribute to the richness of European culture as a whole.

What follows is a journey through that story—from prehistoric carvings to Baroque chapels, from Alpine painters to contemporary installations. Along the way, we will discover the enduring values that shape Alpine art: precision, resilience, reverence, and a deep sense of place.

Prehistoric and Early Celtic Traditions

Long before the Roman legions carved roads through the passes or the Benedictine monks built abbeys on snowy ridges, the people of the Alps were already making marks—some symbolic, some ceremonial, and some purely enigmatic. The art of prehistoric Alpine communities offers a rare and compelling window into a world where geography, survival, and expression were deeply entwined. Though much of it is fragmentary and interpretive, this early visual culture set the foundation for a region that has always valued the fusion of craft, nature, and meaning.

The most famous legacy of Alpine prehistory is the rock art found in the Valcamonica valley of northern Italy. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979, the valley contains over 140,000 petroglyphs carved into glacial rock surfaces, dating from the Epipaleolithic period (c. 8000 BC) through the Iron Age (c. 1st millennium BC). These engravings, made with stone and later metal tools, depict a wide range of subjects: hunting scenes, ploughing, duels, religious symbols, and stylized human figures with open arms—a motif scholars still debate.

The Valcamonica carvings are not isolated. Similar petroglyphs have been discovered throughout the Alpine arc, from Mont Bégo in the French Alps to the Engadin in Switzerland. The widespread presence of this art suggests both shared cultural frameworks and regionally specific traditions. It also hints at the central role of visual communication in societies that left few written records.

While the meanings of these carvings remain elusive, they are undeniably organized and purposeful. In many cases, they appear in clusters, carefully placed on prominent outcrops overlooking valleys or water sources. This positioning supports theories that these were ritualistic or ceremonial sites—spaces where the symbolic and the sacred overlapped. The persistence of certain motifs—horned figures, sun symbols, weapons—across regions indicates enduring themes related to fertility, warfare, territory, and cosmology.

By the Bronze Age, Alpine communities had developed more sophisticated metallurgy, ceramics, and textiles. Decorative motifs on bronze tools and ornaments from this period show a growing emphasis on abstraction and symmetry—often in geometric patterns that would echo through later Alpine folk traditions. Burial sites in regions such as Tyrol and Savoy reveal finely worked grave goods: pins, brooches, belts, and armlets adorned with incised lines, spirals, and crosshatches. These were not merely practical items; they were expressions of status, belief, and aesthetic care.

The arrival of the Celts in the first millennium BC introduced new forms of artistic expression to the Alpine sphere. The La Tène culture, which flourished across much of central Europe from about 450 BC until the Roman conquest, left a distinct mark in the Alpine foothills. Celtic artisans mastered metalwork, producing elaborately decorated weapons, jewelry, and ceremonial objects with curvilinear designs. In areas such as modern-day Switzerland, Austria, and southern Germany, La Tène artifacts were often found in hill forts and burial mounds—evidence of a warrior aristocracy that valued display and symbolism.

One striking example is the bronze and ironwork from the Halstatt and La Tène cemeteries around Lake Neuchâtel. The objects here—swords with ornate hilts, fibulae shaped like animals, and intricately patterned vessels—combine utility with aesthetic sophistication. Though their full iconographic meaning may be lost to time, their formal elegance and technical mastery are unmistakable.

It’s worth noting that the Celts in the Alps were not isolated tribes but active participants in wider trade networks. Amber from the Baltic, Mediterranean pottery, and Greek coins found in Celtic Alpine sites all point to cultural exchange. This dynamic blend of local tradition and outside influence would become a constant in Alpine art history—visible again and again in everything from Roman mosaics to Baroque altar carvings.

What sets early Alpine art apart is not grandeur or monumentality but intimacy and integration with environment. Whether carved into stone, woven into clothing, or cast in bronze, these objects were not made to dominate space but to inhabit it—tactile, portable, and in dialogue with the rhythms of daily and seasonal life. They reflect a worldview in which human beings were part of a larger natural order—an idea that, arguably, has never quite left the Alpine imagination.

By the time the Romans arrived in force during the 1st century BC, the Alps were already dotted with sacred sites, artisan communities, and a coherent, if regionally varied, artistic tradition. Though much would change under Roman rule, the underlying craftsmanship and symbolic fluency of these early cultures would endure—passed down through generations, adapted to new forms, and quietly embedded in what came next.

Roman Influence and Alpine Urbanization

When Roman forces moved into the Alpine regions in the late Republic and early Imperial periods, they did not encounter a blank slate. They met complex communities with established craft traditions, spiritual sites, and strategic control over important passes. But what the Romans brought—and what would leave a lasting impact on the region’s art history—was a system: urban planning, monumental architecture, written culture, and a visual language tied to imperial identity. In absorbing the Alps into the Roman world, they reoriented its artistic development toward classical forms, while still allowing local traditions to persist in adapted ways.

The conquest of the Alps was not a single event but a series of calculated campaigns, culminating in the Augustan era with the establishment of key roads like the Via Claudia Augusta (completed around 15 BC), which connected northern Italy with southern Germany. Along this and other strategic corridors, the Romans founded or expanded urban centers that would become focal points for art and architecture: Augusta Vindelicorum (modern-day Augsburg), Aventicum (Avenches in Switzerland), Aosta, and Chur, among others.

In these towns, Roman visual culture took root quickly. Temples, amphitheaters, baths, and forums introduced new architectural forms to the Alpine landscape. Local stone, particularly limestone and marble, was used for grand construction, often accompanied by painted stucco interiors, mosaic floors, and carved altars. These were not merely copies of Mediterranean designs—they were practical adaptations to local climates and topography, while still communicating imperial order and Roman civic ideals.

Mosaic art flourished in several Alpine centers, often drawing on both Roman mythology and regional iconography. In Aosta, a city often called the “Rome of the Alps,” excavations have revealed fine examples of mosaic pavements, featuring geometric borders and figural scenes drawn from classical mythology. These works, typically located in villas and bath complexes, were not only decorative but symbolic—markers of wealth, literacy, and Romanitas.

Funerary art offers another key lens into Roman influence. Tombstones and sarcophagi found across Alpine cemeteries blend Roman motifs with local names and attire, suggesting a gradual and negotiated cultural integration. In places like Noricum (modern southern Austria), Latin inscriptions coexist with depictions of local dress or Celtic motifs—evidence of hybrid identities.

Sculptural production in the Alpine provinces also reflects this blending. While Roman gods and emperors appear frequently, local cults persisted, often given new life under Roman names or forms. The god Mercury, for example, was often associated with local deities of travel and commerce. Votive reliefs found in Alpine sanctuaries depict Mercury alongside animals, mountains, or regional flora, grounding Roman religion in Alpine nature.

Not all Roman art in the Alps was elite or monumental. Everyday items—ceramic oil lamps, decorated bronze fibulae, terracotta figurines—show the dissemination of Roman aesthetics into domestic life. These objects, mass-produced in workshops but sometimes customized with regional patterns or symbols, were part of a growing material culture that united far-flung parts of the empire while still allowing for local distinction.

Architecture also evolved in Alpine contexts. Town planning respected Roman norms—gridded streets, central forums—but had to contend with Alpine terrain. Cities like Aosta and Sion adapted their layouts to rivers and slopes, and many structures were built with thermal efficiency in mind, a practical concern in mountain climates. Roman engineering expertise—especially in roads, bridges, and aqueducts—was vital to sustaining these towns and connecting them to broader networks.

The Romanization of the Alps was never total. Rural areas continued to practice traditional forms of craft, particularly in woodworking, textile dyeing, and local religious art. Yet over time, the visual vocabulary of Roman art—columns, domes, arches, garlands, acanthus leaves—became normalized, shaping not only what buildings looked like, but what people expected from public space and decoration.

By the 4th century AD, as the Western Roman Empire began to weaken, many Alpine cities declined in population and political importance. But their artistic legacy endured. Christian churches emerged atop former pagan sites. Basilicas replaced temples. Roman roads and foundations became the infrastructure for medieval towns. And the classical visual language continued to echo through the centuries, reinterpreted by every age to follow.

The Roman period in the Alps was not just a time of conquest, but of integration and transformation. Local artisans learned new techniques. Civic leaders commissioned works to assert Roman loyalty. Religious practices adapted their imagery to align with imperial expectations. The Alps were not merely absorbed into Rome—they helped give Rome’s provincial culture its unique regional inflection.

Medieval Sacred Art: Romanesque to Gothic in the High Valleys

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, the Alpine regions underwent a transformation—not a collapse, but a shift. New kingdoms, tribes, and religious authorities gradually filled the vacuum, and the visual culture of the Alps pivoted accordingly. Art in this era was dominated by the Church, not just spiritually but practically—it was the Church that had the literacy, patronage, and institutional continuity to shape what art was made and how it looked. In the Alpine world, where terrain shaped travel and settlement, this meant that churches, monasteries, and chapels became the cultural capitals of their valleys.

The early medieval period (roughly 500–1000 AD) saw the establishment of monastic centers that would define religious and artistic life for centuries. Monasteries like St. Gallen in Switzerland, Müstair in the Grisons, Novalesa near the Mont Cenis Pass, and San Giovanni in Val Müstair became beacons of cultural production. These sites preserved classical learning through scriptoria, created illuminated manuscripts, and commissioned some of the earliest mural paintings in the region.

The Romanesque style (c. 1000–1200), with its rounded arches, heavy masonry, and sober grandeur, took hold throughout the Alpine belt. It was particularly well-suited to the region’s stone supply and seismic challenges. Alpine Romanesque churches are often characterized by massive walls, thick columns, and minimal windows—designed for durability as much as symbolism. Decoration was often concentrated in the apse, portal, or capital sculptures, with themes drawn from Scripture, local saints, and apocalyptic imagery.

Fresco painting became a central medium during this period. Entire interiors were covered in narrative cycles designed to educate a mostly illiterate population through vivid color and symbolism. A superb example is the Church of St. George in Oberzell (on Reichenau Island), where early medieval wall paintings survive in impressive condition. Further south, the Müstair monastery (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) contains some of the most significant Carolingian and Romanesque frescoes in Europe, depicting the life of Christ with a combination of Eastern and Western stylistic elements.

Stone carving also flourished. In places like Sant’Orso in Aosta, cloisters were lined with sculpted capitals featuring biblical scenes, mythical beasts, and allegorical figures. These were not abstract decorations; they were theological statements, visual sermons carved into stone. The Alpine sculptors of this period developed a distinctive, expressive style—less concerned with proportion than with clarity and impact.

The spread of the Gothic style in the 13th and 14th centuries introduced new architectural ambitions to the Alps. Pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses reached even into remote valleys, though on a more modest scale than in the great cathedrals of France or Germany. What made Alpine Gothic unique was its adaptation to scale and terrain. Rather than vast vertical interiors, Alpine Gothic often manifested in finely detailed small churches with vaulted ceilings, decorated tympana, and rich stained glass.

Stained glass, in particular, became a major vehicle of narrative art during this time. Churches in Sion, Lausanne, and Trento commissioned windows that combined biblical stories with local heraldry—emphasizing both faith and civic pride. Alpine glassmakers used regional materials and techniques, creating rich jewel-toned works with delicate linework and occasional secular flourishes.

Manuscript illumination also continued to thrive, especially in monastic centers. The St. Gallen codices remain among the most important artifacts of early medieval learning and artistry, combining musical notation, liturgical text, and ornamental design. While these were not works for public viewing, they show the level of artistic refinement maintained even in seemingly remote monasteries.

One often overlooked element of Alpine medieval art is architecture as pilgrimage infrastructure. With religious routes crisscrossing the Alps—particularly routes to Santiago de Compostela, Rome, and Jerusalem—churches were built to accommodate not only local worshippers but traveling pilgrims. This created a network of Romanesque and Gothic roadside chapels, each featuring local variations on shared iconographic programs.

As the medieval period advanced into the late 14th and early 15th centuries, Alpine art began to reflect transalpine currents more directly. Trade routes brought Germanic and Italian influences into closer contact, and painters like Thomas Schmid in the Tyrol or sculptors in South Bavaria began to work in what’s sometimes called the International Gothic style—elegant, elongated figures, elaborate drapery, and a greater emphasis on realism and emotional expression.

What unifies Alpine sacred art across the medieval period is its synthesis of place and devotion. These works were not anonymous expressions of medieval piety—they were deeply grounded in their valleys, towns, and seasons. The frescoes reflected local flora and weather. The stone carvings often showed animals and tools familiar to the congregation. This rootedness gave Alpine art its character: grounded, symbolic, and enduring.

By the end of the medieval era, the Alps were not merely receivers of cultural influence. They had become contributors—generating their own schools of art, shaping ecclesiastical styles, and sustaining a legacy of craftsmanship that would influence the Renaissance and Baroque periods to come.

Alpine Gothic: Stone, Wood, and Elevation

As Europe moved into the late Middle Ages, the Gothic style transformed the visual landscape of cities and regions across the continent. While its most iconic forms appeared in soaring cathedrals like Chartres and Cologne, Gothic art in the Alps developed along a more regional, materially grounded path—adapted to the challenges of mountain terrain and the tastes of smaller, independent communities. The result was a distinctive Alpine Gothic aesthetic, marked by technical mastery in woodcarving, regional stonework, and a focus on functional ornament rooted in devotion.

By the 13th century, the Gothic vocabulary—pointed arches, rib vaults, tracery, and vertical emphasis—had reached nearly every major Alpine region. But Alpine towns, many of which were small bishoprics or monastic centers rather than royal capitals, rarely built on the scale of northern France or the Rhineland. Instead, they interpreted Gothic forms within existing Romanesque traditions and built with the materials they had in abundance: local limestone, granite, larch, and fir.

This meant that while Alpine Gothic churches might lack monumental scale, they often exhibited extraordinary craftsmanship. Take, for example, the Collegiate Church of Sant’Orso in Aosta. Though modest in size, it features a beautifully preserved cloister with sculpted capitals that show a Gothic fluidity layered onto Romanesque solidity. Similarly, the Liebfrauenkirche in Rankweil, Austria, is a small hilltop church with slender Gothic windows and delicate tracery, built to echo the Gothic ideal in a compact, terrain-conscious design.

In Alpine towns like Bolzano, Innsbruck, and Chur, local guilds and patrons funded Gothic chapels, town halls, and cloisters that combined civic pride with spiritual reverence. These commissions were often executed by local stonemasons and imported craftsmen from Swabia, Franconia, or Lombardy—resulting in a cross-pollination of Central European Gothic styles with local adaptations.

But the real hallmark of Alpine Gothic was its woodwork.

Nowhere in Europe was the tradition of ecclesiastical woodcarving more developed than in the Alps. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, the region became a hub for altarpiece production, supplying elaborately carved and polychromed retables to churches across southern Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and northern Italy.

Artists such as Michael Pacher (1435–1498), based in Bruneck (South Tyrol), were among the first to fully integrate sculpture and painting into unified altarpieces. Pacher’s works—like the renowned St. Wolfgang Altarpiece—feature towering, multi-paneled wooden constructions combining relief sculpture with painted narratives, all set within Gothic architectural frameworks. His style blends the spatial depth and realism of the Italian Renaissance with the expressive detail of German Gothic carving, and his influence spread widely through the region.

Another master, Hans Multscher of Ulm, worked in both Tyrol and Swabia, creating altarpieces and statuary marked by fine facial modeling and complex drapery. His sculptures of saints and apostles, often commissioned for remote Alpine churches, reflect a dignity and craftsmanship that made even the smallest parishes feel connected to the great artistic movements of the age.

Alpine sculptors typically worked in limewood or Swiss pine, both abundant and easy to carve. These woods allowed for extreme detail, particularly in facial expressions and clothing folds. Once carved, figures were polychromed—painted in rich colors and often gilded with gold leaf. The resulting works were not only devotional tools but visual spectacles, designed to inspire awe and connect parishioners with biblical narratives in an era of limited literacy.

Besides altarpieces, Alpine Gothic also expressed itself in choir stalls, pulpits, and confessionals—functional furnishings turned into works of art. In some monasteries, even the monastic cells featured carved and painted devotional panels, showing the extent to which religious life was intertwined with the visual arts.

Stained glass also found a place in Alpine Gothic churches, though in smaller lancet windows rather than grand rose windows. The glasswork from this period often emphasized intimacy and detail over spectacle, using deep blues and reds to depict Christ, Mary, or the patron saints of a region. Surviving examples in Brixen, Lausanne, and Sion showcase a blend of Gothic iconography with Alpine realism—figures set against mountainous landscapes or surrounded by locally known flora.

Secular Gothic architecture, while less common in the Alps, did appear in fortified towns and burgher houses, particularly in areas like Lucerne, Merano, and Salzburg. These buildings featured steep gables, pointed windows, decorative frescos, and internal wood paneling that matched the quality of church interiors. The visual language of Gothic thus permeated not only religious life but also the homes of the urban elite.

By the late 15th century, as Renaissance humanism began filtering northward, Alpine Gothic began to evolve. Sculptors and painters introduced more naturalistic proportions, linear perspective, and classical motifs. Yet the Gothic sensibility—rooted in verticality, symbolism, and expressive craftsmanship—remained strong well into the 16th century in more remote valleys and conservative patrons’ commissions.

The legacy of Alpine Gothic lies in its technical excellence and regional adaptation. Rather than mimic the scale and spectacle of Gothic centers like Chartres or Cologne, Alpine artisans emphasized intimacy, devotion, and material mastery. They carved, painted, and built with an understanding of place—responding to stone, wood, and mountain with skill, patience, and purpose.

Renaissance Currents in the Alpine Sphere

The Renaissance is often viewed as a movement radiating outward from Florence, Rome, and Venice—a rebirth of classical ideals carried by humanists, architects, and painters into the courts and cities of Europe. Yet even the seemingly remote regions of the Alps felt its influence. While the Renaissance in the Alpine sphere did not arrive with the same immediacy or intensity as in Italy, it made a significant and lasting mark, especially in urban centers along trade routes and in bishoprics with strong cross-alpine connections.

Renaissance art in the Alps was shaped not by revolution, but by assimilation and adaptation. Gothic traditions did not disappear; rather, they evolved under the influence of classical proportion, perspective, and humanist ideals. Artists and patrons selectively embraced these innovations, often blending them with regional motifs and techniques. The result was a Renaissance style that remained recognizably Alpine in materials and mood, yet clearly part of a larger European movement.

Transmission Through Trade and Patronage

Key to the spread of Renaissance forms into the Alps were the merchant networks and ecclesiastical ties that connected the region to Italy, Bavaria, and Swabia. Cities like Augsburg, Basel, and Innsbruck served as conduits for artistic exchange. Wealthy merchant families, bishops, and noble patrons commissioned works that reflected their knowledge of Italian art and their desire to associate with the cultural prestige of the Renaissance.

The Fugger family of Augsburg, perhaps the wealthiest bankers in Europe, played a pivotal role in bringing Renaissance architecture and sculpture into southern Germany and the Alpine frontier. Their chapels and civic projects were often designed by architects influenced by Brunelleschi and Alberti, and decorated by artists who had traveled to Italy.

Painters Between Worlds

One of the earliest and most influential painters to bridge this stylistic shift was Hans Holbein the Elder (c. 1460–1524), based in Augsburg but with commissions across southern Germany and Switzerland. His altarpieces show a transition from Gothic stylization to a more controlled space and anatomical accuracy. His sons, especially Hans Holbein the Younger, would go on to achieve international renown, though their work was more associated with the courts of northern Europe than the mountains.

In the Tyrol and South Tyrol, painters such as Leonhard von Keutschach and Bartholomäus Zeitblom introduced softer modeling, architectural backdrops, and classical detail into religious panels. While their figures still bore Gothic elongation and expression, the surrounding architecture and spatial arrangement reflected Renaissance order.

One of the most compelling local interpreters of the Renaissance was Jörg Kölderer, court painter and architect to Emperor Maximilian I, whose court in Innsbruck became a cultural beacon in the early 16th century. Kölderer’s works combine late Gothic expressiveness with Italianate symmetry, showing how the imperial court helped shape regional tastes.

Sculpture and Architecture

Sculpture also underwent refinement in the Alpine Renaissance. The late Gothic woodcarvers of the 15th century were succeeded by artists who introduced greater realism, classical drapery, and individualized portraiture into their figures. Innsbruck’s Hofkirche, commissioned by Emperor Ferdinand I to honor his grandfather Maximilian, contains a remarkable series of bronze statues (Schwarzmander) cast by artists trained in Renaissance techniques but executed with a northern weight and gravity.

In architecture, the Renaissance brought symmetry, measured proportions, and columned façades to Alpine cities—particularly in urban rebuilding and civic projects. In places like Brixen, Feldkirch, and Merano, buildings began to adopt rounded arches, pediments, and harmonious proportions. While the Gothic verticality lingered in ecclesiastical buildings, Renaissance civic architecture emphasized balance and horizontality.

In Switzerland, particularly in the southern canton of Ticino, the proximity to Lombardy made the influence of the Italian Renaissance stronger and more direct. Lugano and Bellinzona saw early adoption of classical architectural features, and artisans from this region played an important role in spreading Renaissance building styles northward.

Printing and the Spread of Ideas

Equally important was the rise of printing in Alpine cities like Basel, which became a hub of Reformation-era intellectual life. Though this would have a more dramatic impact in the next century, the ability to circulate engravings, treatises on perspective, and architectural manuals helped spread Renaissance aesthetics to a wider audience of craftsmen, patrons, and builders.

Artists could now access printed images of classical ruins, ideal proportions, and religious compositions by Italian masters. This exposure didn’t result in direct imitation so much as translation—Italian models interpreted through northern sensibilities and Alpine practicalities.

Religious Themes and Continuity

Despite these shifts, religious art remained dominant. The Alps were still part of a deeply Catholic landscape, even as Reformation currents began to stir in the north. Renaissance art in the region continued to focus on altarpieces, church murals, and ecclesiastical sculpture, with classical elements enhancing rather than replacing spiritual content.

By the late 16th century, the Council of Trent and the Catholic Reformation would usher in a more dramatic change in Alpine art, leading to the expressive dynamism of the Baroque. But in the Renaissance phase, the emphasis remained on harmony, dignity, and measured transformation—a visual transition as steady and deliberate as the paths carved through the mountain passes.

Woodcut Masters and the Printed Image

If the Renaissance brought new ideals and classical forms to the Alps, it was the print revolution that truly democratized visual culture in the region. From the late 15th century onward, Alpine towns became key centers for the production and distribution of woodcuts and engravings—forms of reproducible art that carried both religious imagery and emerging humanist ideas far beyond the walls of churches or aristocratic homes.

Among the most important Alpine cities in this story are Nuremberg, Basel, and Augsburg. Though not deep in the high mountains, these cities were closely tied to the Alpine world through trade routes and religious networks. Each developed robust workshops where art and printmaking flourished, driven by a combination of literacy, commerce, and faith.

The Woodcut as a Medium of the Alps

The woodcut, carved into blocks of pear or boxwood and printed on handmade paper, was the dominant method of image reproduction in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Its bold lines and clear contrasts made it ideally suited to devotional subjects, biblical scenes, saints’ lives, and even local legends—subjects that Alpine audiences knew well and valued.

These prints were affordable and portable, meaning they could reach rural towns, alpine monasteries, and village chapels. They were pasted on walls, inserted into books, or framed for private devotion. For many, they were the first and only form of art ownership, offering a direct way to visualize stories of faith and morality.

Albrecht Dürer and the Alpine Imagination

No name looms larger in this era than Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Though based in Nuremberg, Dürer traveled extensively in the Alps and frequently depicted its landscapes in his drawings and watercolors. His prints—particularly his series on the Passion of Christ and The Apocalypse—were widely circulated and had a profound impact on Alpine visual culture.

Dürer’s prints combined theological rigor with artistic refinement. His woodcuts used dramatic perspective, expressive faces, and carefully constructed settings to elevate biblical stories into both art and instruction. Many Alpine artists, particularly in southern Germany and western Austria, studied and copied Dürer’s prints. The standardization of visual themes, especially in depictions of saints, martyrdom, and Last Judgment scenes, can be directly traced to his influence.

His 1494–95 journey through the Alps to Italy left a visual legacy in the form of detailed mountain studies, capturing not only dramatic peaks but also quiet valleys, farmhouses, and alpine towns. These works helped shift the idea of the Alps in northern European art—from a forbidding wilderness to a place of beauty, structure, and human presence.

Basel and the Printing Press

In Switzerland, Basel became a powerhouse of the printing world. Printers like Johann Froben and Johann Amerbach produced editions of the Bible, classical texts, and theological works, often adorned with woodcut illustrations. These prints helped shape the visual understanding of sacred history and doctrine during a time of religious change.

Hans Holbein the Younger, born in Augsburg and active in Basel, contributed significantly to book illustration and print design before his English career. His Dance of Death series (1523–1526), a masterful woodcut sequence showing Death interrupting people of all social ranks, reflected both medieval themes and Renaissance execution—blending moral gravity with technical elegance.

The Role of Local Workshops

Alongside the great names were hundreds of regional woodcutters and engravers, many of them anonymous, who populated Alpine villages and towns with prints. These workshops produced devotional images, ex-voto prints, saint calendars, and illustrated broadsheets tailored to local saints and festivals. Some included specific alpine landmarks or traditional clothing—rooting biblical narratives in familiar visual terrain.

These popular prints became part of the Alpine material culture, often surviving for generations in homes or being recopied by folk artists into wall paintings and carved panels. The durability of these images—reproduced again and again—meant that certain styles and motifs became deeply embedded in local memory.

The Engraving and the Protestant Reformation

By the early 16th century, engraving—using copper plates rather than wood—allowed for even finer detail. Artists like Heinrich Aldegrever and Daniel Hopfer, both working in southern Germany, created engraved prints that circulated throughout the Alpine world. Their works often tackled Reformation themes, contrasting biblical authority with what Reformers saw as the corruption of the Church.

In this context, prints became tools of persuasion. Protestant and Catholic artists alike used visual media to argue their case—depicting scenes of proper worship, the sacraments, or critiques of clergy. In the Alps, where religious allegiance varied from valley to valley, these prints both mirrored and shaped the era’s turbulent debates.

Legacy of the Print in Alpine Art

The Alpine woodcut tradition gave rise to a broader culture of accessible religious art. Even after the peak of Renaissance printing, the aesthetic of woodcut—the strong outlines, narrative clarity, and didactic tone—remained visible in folk art, ex-voto panels, and devotional chapbooks throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

The print revolution also expanded the concept of the artist in Alpine regions. Art was no longer confined to altar commissions or noble patronage. A skilled printmaker could earn a living by selling images across markets and fairs, reaching audiences far beyond their village or region.

Ultimately, the woodcut and the printed image brought the Renaissance and its visual ideas to a wider Alpine public. It helped standardize sacred iconography, spread humanist learning, and make art a daily presence even in the remotest mountain valleys.

Baroque and Rococo in the Alps: Art of Faith and Majesty

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Alpine world entered an era of visual splendor. As the religious tensions of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation reshaped Europe, the Catholic Church in the Alps—especially in Austria, Bavaria, and parts of Switzerland and northern Italy—turned to art as a means of reaffirming faith and ecclesiastical authority. This was the age of the Baroque and, later, the Rococo—styles that prized grandeur, dynamism, theatricality, and ornament. The result was a flowering of sacred art and architecture across Alpine valleys that rivaled anything in Europe, albeit on a more regionally attuned scale.

While cities like Rome and Vienna set the tone for high Baroque aesthetics, the Alps developed their own versions—rooted in local craftsmanship, adapted to mountain topography, and often infused with pastoral imagery. Here, in the shadows of snow-covered peaks, artists, masons, and stucco masters created churches and chapels that gleamed with light, movement, and exuberance, turning even the remotest pilgrimage site into a stage for heavenly spectacle.

Baroque Architecture in Alpine Towns

In Catholic strongholds such as Salzburg, Innsbruck, Brixen, and Einsiedeln, Baroque church building reached impressive heights. Architects like Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach and Jakob Prandtauer brought classical order, monumental façades, and oval domes to Alpine cities, creating churches and monasteries that blended imperial architecture with devotional space.

The Salzburg Cathedral, rebuilt in the Baroque style after fires in the 16th century, stands as one of the finest early examples of Alpine Baroque. Its twin towers, symmetrical layout, and stuccoed interior represent the clarity and controlled grandeur of early Baroque design. Similarly, the Collegiate Church of St. Gall in Switzerland—now a UNESCO World Heritage Site—was rebuilt in the Baroque style by Peter Thumb, with sweeping white interiors and gilded ornament that reflect the Catholic ideal of divine order made visible.

Even smaller villages invested in impressive Baroque churches. Alpine communities poured their resources into commissioning altars, pulpits, and frescoes that turned their parish churches into miniature theaters of salvation. These churches were not just religious centers—they were expressions of civic pride and identity.

The Rise of Rococo: Ornament in Elevation

By the mid-18th century, the more restrained forms of Baroque architecture began giving way to the Rococo—a lighter, more playful style that emphasized surface decoration, asymmetry, pastel colors, and illusionistic ceiling paintings. This style suited the smaller spatial scale of Alpine churches and allowed for remarkable local innovation.

The Wieskirche in Bavaria, designed by Dominikus Zimmermann, is a prime example of Alpine Rococo. Its interior glows with soft light, curling stucco vines, delicate frescoes, and a central image of the Scourged Savior, combining emotional piety with visual joy. The church became a major pilgrimage site and a model for many Alpine builders who sought to blend spiritual message with artistic flourish.

In Tyrol and the Engadin, Rococo churches often featured ceiling frescoes depicting the Virgin Mary, Christ, and the saints floating amid clouds, framed by stucco angels and floral garlands. These spaces were immersive—designed to elevate the worshipper into a vision of the celestial. Local artisans, trained in both painting and plaster, worked collaboratively to create unified decorative programs.

Master Craftsmen of the Alps

One of the most celebrated families of the Alpine Baroque and Rococo period were the Asam brothers—Cosmas Damian (painter and architect) and Egid Quirin (sculptor and stuccoist)—based in Bavaria but working across the Alpine sphere. Their work in churches like the Asamkirche in Munich and the Abbey Church at Weltenburg demonstrates the height of integrated design: architecture, sculpture, painting, and ornament all working together in service of dramatic storytelling.

In Switzerland, Franz Ludwig Wind and other stucco artists brought Rococo elegance to rural parishes. In Austria, Paul Troger, a painter of monumental ceiling frescoes, created luminous compositions filled with soft light, spiritual ecstasy, and theatrical movement. His works—especially in monastic settings—were visual sermons, leading the viewer’s eye upward toward divine revelation.

Woodcarving also thrived during this period. In the Tyrol, South Bavaria, and Vorarlberg, churches commissioned elaborate Rococo pulpits, organ lofts, and choir stalls, often gilded and adorned with twisting Solomonic columns, cherubs, and symbolic motifs. These were expressions of piety and local skill, executed by workshops that had been refining their craft since the Gothic period.

Music and Visual Art: A Shared Language

The Alpine Baroque was not only visual—it was also deeply connected to the rise of sacred music. Organs were installed in newly built churches, and their decorative cases were designed to match the overall aesthetic. Composers like Michael Haydn in Salzburg and Benedikt Anton Aufschnaiter in Innsbruck worked in tandem with visual artists to create holistic worship experiences—aural and visual unity that elevated the Catholic liturgy.

Pilgrimage and Regional Identity

Many of the most striking Baroque and Rococo churches in the Alps were built at pilgrimage sites, often connected to miraculous images or Marian devotion. These remote chapels—sometimes accessible only by mountain paths—were designed to be destinations of wonder. Their richly decorated interiors provided a reward for the journey, a foretaste of the divine in art.

These churches also reinforced regional identity. Frescoes often included local landscapes, coats of arms, or famous historical events, anchoring the sacred in the familiar. Even amid stylistic internationalism, Alpine artists never forgot where they were. Their art, though ornate and cosmopolitan, remained grounded in place, tradition, and faith.

Folk Art and Vernacular Traditions

Beyond the grandeur of cathedrals and the formal elegance of court-sponsored painting, the Alps have long nurtured a parallel tradition of folk art—art made by and for local communities, grounded in daily life, seasonal rhythms, and ancestral memory. While less studied than high art, these vernacular expressions offer a crucial window into the Alpine spirit: practical, devotional, regionally distinctive, and deeply connected to place.

Folk art in the Alps was not produced in academies or under royal patronage. It was the work of village craftsmen, farmers, woodworkers, and religious lay communities, often anonymous, sometimes itinerant, but almost always locally embedded. From painted furniture to carved religious figures, from decorative ironwork to embroidered costumes, these objects were not made as commodities—they were part of life itself.

Wood: The Alpine Medium

Wood was the most accessible and important material in Alpine folk art. Entire villages were built from it, and generations of craftsmen turned it into both tools and ornament. In Tyrol, Valais, Vorarlberg, and Graubünden, local artisans developed a rich tradition of decorated furniture—chests, wardrobes, benches, and beds painted with floral motifs, birds, suns, and initials. The color palette was bold—often deep reds, greens, and ochres—with stylized natural forms and geometric borders.

Many pieces were personalized, bearing family crests, religious inscriptions, or marriage dates, and passed down through generations. These objects functioned as both heirlooms and household altars—expressions of continuity and identity in often isolated communities.

Alpine woodcarving also flourished in the form of devotional figures, particularly crucifixes, Madonnas, and saints. These sculptures were rarely anatomically perfect or stylistically refined by academic standards, but they carried powerful emotional weight. Found in roadside chapels, bedroom niches, and communal shrines, they provided spiritual reassurance and connected the rhythms of village life to the liturgical calendar.

Painted Wall Murals and Rural Churches

Even modest rural churches in the Alps often featured folk-style frescoes—scenes from the Passion, Marian miracles, or the lives of local saints, painted directly on whitewashed walls. These works were less concerned with perspective or proportion than with clarity and emotional immediacy. They drew on the long tradition of sacred storytelling, using direct visual language to communicate with congregations.

Sometimes, these murals included local details—alpine meadows, traditional costumes, regional animals—rooting the biblical narrative in a familiar world. This practice reinforced religious teaching while also affirming community identity.

House Façades and Painted Exteriors

In regions like Upper Bavaria, South Tyrol, and Engadine, house painting became a distinct folk tradition. Entire building façades were decorated with painted window frames, corner columns, and narrative scenes—a practice known as Lüftlmalerei in German-speaking areas. These images often combined religious motifs (such as saints or blessings) with secular themes: agricultural life, hunting, folk tales, or family history.

These houses not only beautified the village landscape but served as visual markers of local pride, craftsmanship, and prosperity. They also functioned symbolically—projecting faith, morality, and tradition into the public sphere.

Textiles and Costume: Art Worn Daily

Another major outlet for Alpine folk expression was in textile arts. Women played a central role here, passing down skills in embroidery, weaving, and lace-making. Festive clothing—Trachten in German-speaking areas—was elaborately decorated with stitched floral patterns, silver clasps, and braided cords, with styles varying from valley to valley.

These costumes were more than fashion; they were cultural codices, identifying marital status, village of origin, and social role. On feast days and during processions, they turned the community into a moving artwork—visually reinforcing shared identity and historical continuity.

Blankets, tablecloths, and ceremonial banners were also richly decorated, often with initials, Christian symbols, and heraldic devices. The domestic and the sacred were closely linked in these forms, and the level of detail and skill rivals that found in more celebrated art forms.

Ironwork, Horn Carving, and Craftsmanship

The Alpine folk tradition extended into metal and horn, particularly in practical items that were often elevated by decoration. Cowbells, fireplace tools, knife handles, and lock plates were engraved or shaped with patterns that blended function with beauty. Horn carving, practiced especially in Swiss and Austrian regions, was used for flasks, spoons, and pipes, adorned with hunting scenes, family emblems, or alpine animals.

These crafts reflected a worldview in which daily objects could and should be beautiful, not as luxury but as a matter of pride and dignity.

The Continuity of Folk Forms

One of the most remarkable aspects of Alpine folk art is its resilience. Unlike court or religious art, which shifted dramatically with fashion and theology, folk forms remained relatively stable over centuries. A painted chest from the 18th century and one made in the 20th might look nearly identical. This continuity speaks not to stagnation but to a deep cultural confidence—a belief in the worth of local tradition.

Even today, folk art remains vital in Alpine life. Festivals, craft schools, and heritage associations keep these forms alive. Contemporary artisans reinterpret them with modern tools and materials, but the spirit remains the same: rooted, personal, and enduring.

The Alpine Landscape in 18th and 19th Century Painting

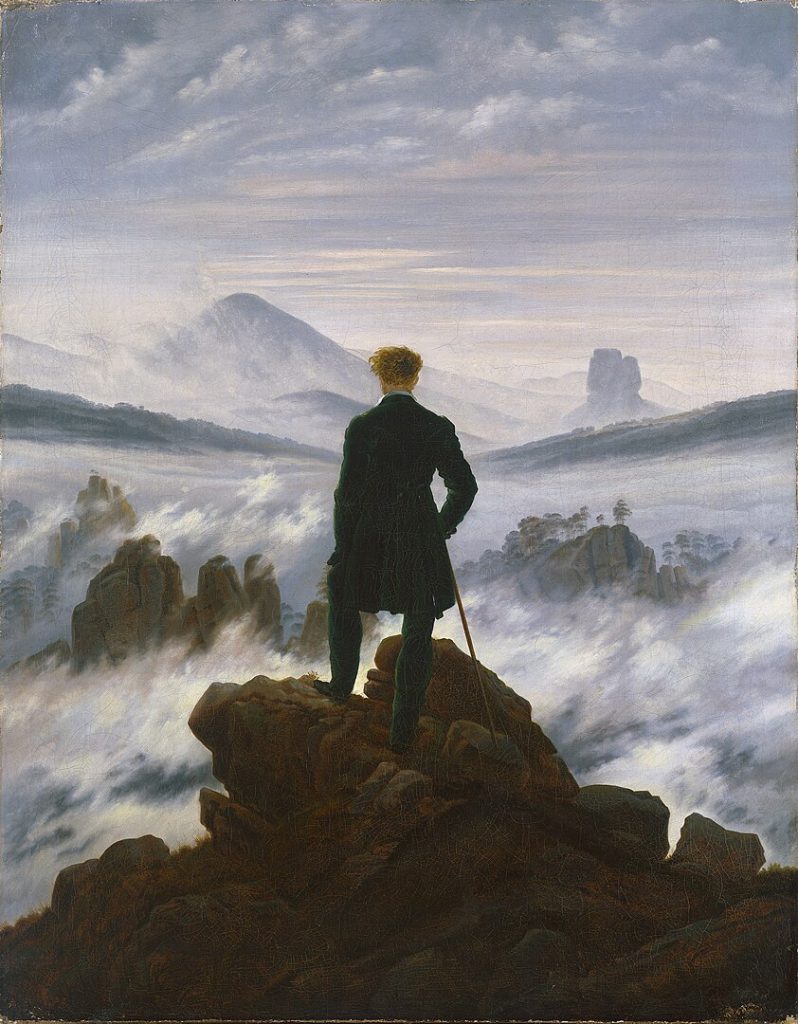

By the 18th century, the Alps had undergone a dramatic shift in the European imagination. What had long been seen as a dangerous, inhospitable wilderness—home to avalanches, superstitions, and solitude—was increasingly viewed as a realm of sublime beauty, national identity, and natural grandeur. This transformation was nowhere more evident than in the art of the time, where the Alpine landscape itself became the subject of study, admiration, and idealization.

Artists across Europe turned their attention to the mountains not merely as backgrounds for religious or mythological scenes, but as worthy subjects in their own right. For Alpine painters and traveling artists alike, this era marked the emergence of landscape painting as a central genre—and the Alps, with their soaring peaks, glaciers, lakes, and rural villages, provided a perfect stage.

The Rise of the Sublime and Romanticism

The concept of the sublime, championed by writers and thinkers such as Edmund Burke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, was key to changing perceptions of mountainous terrain. Rather than something to fear, the Alps came to symbolize the awe-inspiring power of nature—terrifying and beautiful, humbling and eternal. Artists responded by depicting vast skies, deep valleys, turbulent weather, and the play of light across ice and stone.

Painters such as Caspar Wolf (1735–1783), active in Switzerland, became pioneers of the Alpine sublime. His views of glaciers, waterfalls, and high mountain passes—often dramatic, with looming clouds and tiny human figures—helped shift Alpine scenery into a subject of scientific curiosity and emotional impact. Wolf worked closely with patrons from the Enlightenment, including geologists and travelers, combining aesthetic ambition with topographical precision.

National Identity and the Alpine Image

In the 19th century, as European nations sought to consolidate their identities, the Alps played an increasing symbolic role. In Switzerland, Austria, Bavaria, and Italy, the mountain landscape was held up as a symbol of purity, resilience, and natural order. Artists contributed to this national iconography by painting images that balanced realism with idealism—pastoral scenes, majestic peaks, and heroic rural life.

Alexandre Calame (1810–1864) is a defining figure in this period. A Swiss painter based in Geneva, he created grand compositions of the Bernese Alps and alpine lakes, characterized by meticulous attention to rock formations, cloud structures, and light effects. His works, collected across Europe, were seen as emblems of Swiss national identity—quietly heroic, enduring, and harmonious.

Similarly, in Austria, painters such as Josef Brandt and Friedrich Gauermann portrayed alpine farmers, hunters, and animals with romantic dignity, reinforcing rural life as the moral backbone of the nation. Their paintings often emphasized the harmony between man and nature—idealized but rooted in observation.

Topographic Painting and Travel Culture

With the rise of the Grand Tour and later the Alpine spa and mountaineering cultures, demand grew for accurate and picturesque depictions of Alpine locations. Artists were commissioned to create topographical landscapes—clear, identifiable views of famous peaks, valleys, and towns. These were collected by tourists, included in travel books, or used for promotional lithographs.

The work of Thomas Ender, an Austrian artist who painted across the Alps, offers a blend of scientific documentation and artistic refinement. His watercolors and oil paintings captured panoramic vistas with clarity and restraint, satisfying both the curiosity of travelers and the aesthetic demands of collectors.

Engraving and printmaking also flourished during this time. Alpine views were reproduced in books, almanacs, and portfolios, spreading images of the mountains across Europe and America. These prints served both as souvenirs and as ideological tools—presenting the Alps as sites of natural order, health, and moral uplift.

The Human Figure in the Landscape

While many landscapes focused purely on nature, others integrated rural life and tradition. Painters such as Rudolf Koller depicted cows, herdsmen, and village festivals in alpine settings—combining landscape with genre painting. These works reinforced the idea of the Alps not only as visually stunning, but as inhabited, productive, and culturally rich.

These images often carried a quiet conservatism: they idealized tradition, emphasized continuity, and presented rural society as stable and virtuous in contrast to the tumult of industrial cities. In this way, Alpine painting contributed to broader 19th-century cultural narratives about nature, order, and identity.

Scientific Observation and Artistic Detail

The 19th century also saw a growing alliance between science and art. Alpine painters worked alongside geologists, botanists, and early climatologists, providing illustrations of glaciers, plant life, and terrain formations. These images—used in scientific publications, museum displays, and teaching materials—blurred the lines between art and documentation.

Artists such as Joseph Anton Koch, though based in Rome, drew heavily on his early experiences in Tyrol, incorporating mountain motifs into classical compositions. His “heroic landscapes” sought to fuse ideal beauty with geographic accuracy, aligning Romantic ideals with Enlightenment order.

20th Century Modernism and Regional Identity

The 20th century brought monumental changes to Europe, and the Alpine world was no exception. Two world wars, political upheaval, industrialization, and the redefinition of national borders all left their mark on the region. In art, these disruptions produced a wave of innovation, introspection, and reassertion of regional identity. While the avant-garde movements of the 20th century—Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, and abstraction—had their epicenters in major urban capitals, their echoes reached deep into the Alps. What emerged was a distinctly Alpine modernism, informed by contemporary ideas but shaped by place, tradition, and a deep awareness of the landscape.

From Tradition to Modernism: A Gradual Shift

Unlike the radical break with tradition seen in Paris or Berlin, modernism in the Alps was often more evolutionary than revolutionary. Many artists trained in academic realism or romantic landscape traditions slowly began to experiment with new forms—simplifying shapes, flattening perspective, and using color expressively rather than descriptively.

In Switzerland, painters such as Giovanni Giacometti (father of Alberto Giacometti) and Ferdinand Hodler played pivotal roles in bridging 19th-century symbolism with modern abstraction. Hodler, in particular, developed a style he called “parallelism”, characterized by symmetrical compositions and rhythmic forms inspired by the Alps’ natural geometry. His large-scale alpine landscapes—lake shores, mountain ridges, and dawn-lit skies—were both deeply Swiss and boldly modern.

Expressionism and the Mountain Psyche

In Austria and southern Germany, artists associated with Expressionism found in the Alps a potent subject. The dramatic topography, isolated villages, and seasonal extremes lent themselves to intense emotional interpretation. Artists like Albin Egger-Lienz combined rural themes with monumental forms, depicting Tyrolean peasants and war scenes with a stark, sculptural style.

The Blaue Reiter group, though primarily based in Munich, frequently painted in the Bavarian and Austrian Alps. Franz Marc, for instance, produced vibrant, semi-abstract depictions of animals and landscapes that conveyed spiritual unity with nature. These artists saw the Alpine world not only as subject matter, but as a refuge from modern alienation—a place where color, form, and meaning could be reconnected.

Alpine Artists and National Identity

Throughout the century, Alpine countries used art to bolster a sense of cultural continuity and national identity. In postwar Austria and Switzerland, regional artists celebrated mountain life, rural customs, and architectural heritage in a modern idiom—free from the academic constraints of the 19th century, but still grounded in local subject matter.

The 1930s and 1940s, however, saw more troubling appropriations. In Nazi Germany, the Alps were idealized as a homeland of strength, purity, and tradition, and art was used to support that narrative. Artists working in regions like Berchtesgaden or Tyrol were often commissioned to create idyllic mountain scenes and heroic portrayals of rural life. Though technically accomplished, these works were bound to political ideology and became tainted by association.

In contrast, post-1945 artists in the Alpine world sought to reclaim the landscape from ideology. Painters like Arnold Kübler in Switzerland and Max Weiler in Austria returned to mountain subjects with a more introspective, sometimes abstract sensibility—treating the land not as national symbol but as a source of metaphysical reflection.

Modern Materials, Traditional Motifs

Mid-century Alpine modernism often featured a fusion of local themes with modern techniques. Artists used linocut, woodcut, and mixed media to reinterpret folk symbols, alpine animals, and religious imagery. The goal was not nostalgia, but renewal—keeping traditions alive while giving them new visual life.

In architecture, this balance of old and new found expression in the work of regional modernists who designed churches, schools, and civic buildings using concrete, steel, and glass, but with forms inspired by local barns, chalets, and village layouts. The 1950s and ’60s saw a surge in this type of contextual modernism, particularly in Switzerland and western Austria.

Postwar Art Schools and Cultural Institutions

The 20th century also saw the establishment of regional art schools and museums that helped sustain and promote Alpine modernism. Cities like Lausanne, Salzburg, and Bolzano became centers of training and exhibition. These institutions offered artists access to international trends while encouraging them to engage with local heritage and environmental concerns.

In particular, the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, the Kunstuniversität in Linz, and the Kunsthaus Zürich all played key roles in shaping the regional artistic landscape. Artists who trained in Paris or Milan often returned to Alpine towns to teach, exhibit, and build a new visual language rooted in both place and innovation.

Abstract and Environmental Trends

By the 1970s and 1980s, some Alpine artists began moving toward full abstraction, conceptual art, and environmental installation. The mountains, valleys, and seasonal changes were no longer just motifs—they became materials and subjects in themselves.

Artists such as Roman Signer, from Appenzell, created performances and sculptures that explored gravity, time, and natural force—often using simple objects like barrels, skis, and explosives set against alpine backdrops. His work, while minimalist in form, continued the Alpine tradition of responding directly to nature.

Contemporary Art and Alpine Heritage

In the 21st century, Alpine art has entered a dynamic phase of renewal and reflection. Today’s artists working in the Alps—whether native to the region or drawn to it—engage with both deep-rooted heritage and global currents. They operate in a landscape where tradition is still visible in every valley and chapel, but where climate change, tourism, and cultural globalization have reshaped the Alpine environment in profound ways.

Rather than abandoning the past, contemporary Alpine artists often reengage with it, reinterpreting historical forms through new materials, technologies, and critical perspectives. Whether through installation, video, architecture, or community-based projects, today’s Alpine art continues the region’s long-standing emphasis on craftsmanship, site-specificity, and dialogue with nature.

Preserving and Reimagining Alpine Identity

In many Alpine regions, artists and institutions have taken active roles in preserving cultural memory—but not through passive nostalgia. Instead, they use heritage as a source of dialogue and tension, asking what it means to inherit, transform, and transmit.

The Museo Etnografico in Trento, the Freilichtmuseum Ballenberg in Switzerland, and the Vorarlberg Museum in Austria all exhibit traditional art alongside modern reinterpretations. These institutions often collaborate with contemporary artists to juxtapose old and new, sparking conversations between folk objects and conceptual installations.

Projects like Art Safiental, an outdoor biennial in the Swiss Alps, commission site-specific works that interact directly with the landscape. Past installations have included wind-sensitive sculptures, weather-recording devices, and temporary shelters made from local materials. These works reflect both environmental awareness and the long Alpine tradition of building and adapting to terrain.

Climate and Landscape as Contemporary Themes

Today’s Alpine artists are increasingly concerned with ecology, sustainability, and the visual impact of environmental change. Melting glaciers, forest degradation, and seasonal instability are not abstract concerns in this region—they’re daily realities. Artists like Ursula Biemann and Julian Charrière incorporate scientific data, video, and performance to explore the intersection of art, climate, and geography.

In sculpture and land art, materials like stone, water, wood, and ice are used to make temporary, evolving works that reflect the fragility of the landscape. These are not monuments, but gestures—intended to raise awareness, not dominate space.

Architecture and Design: Contemporary Vernacular

Architecture in the Alps continues to be a major site of aesthetic and cultural innovation. In recent decades, Alpine regions—particularly Vorarlberg in Austria and Graubünden in Switzerland—have become leaders in contextual architecture: buildings that use modern materials but maintain harmony with traditional forms and natural surroundings.

Architects like Peter Zumthor (Therme Vals, Kunsthaus Bregenz) and firms like Gion A. Caminada and Baumschlager Eberle design structures that are both functional and quietly monumental. Their works use wood, stone, and glass with restraint, often echoing the forms of historic farmhouses, barns, and chapels. These buildings are not simply aesthetic objects—they are acts of cultural stewardship.

This architectural approach has inspired parallel developments in design and applied arts, from contemporary furniture and ceramics to textile studios that reinterpret traditional Alpine patterns with modern aesthetics.

Art Festivals, Residencies, and Global Exchange

Alpine regions today host a growing number of international art festivals, biennials, and artist residencies. These include:

- Art Safiental (Switzerland)

- Biennale Gherdëina (Val Gardena, Italy)

- Sommerfrische Kunst (Bad Gastein, Austria)

- LUMA Arles / LUMA Westbau (Switzerland-France axis)

These events bring together local and international creators, scholars, and visitors. Crucially, they are often designed to integrate with communities, not impose upon them. Installations appear in barns, meadows, churches, and disused ski lifts, ensuring that art remains embedded in everyday Alpine life.

Many contemporary artists also use these platforms to critique mass tourism, regional branding, and the aestheticization of rural poverty. They are not interested in selling a postcard version of the Alps, but in asking hard questions about what is lost—and what can be preserved—in the face of economic and environmental pressure.

Technology and Craft in Dialogue

Today’s Alpine art scene often blends traditional materials and methods—wood carving, textile weaving, ironwork—with digital tools. Artists 3D-scan glaciers, map folklore with augmented reality, or simulate traditional dance through motion capture. The result is not a loss of identity, but a new articulation of it.

Initiatives like Swissnex and Austrian Cultural Forum promote cross-disciplinary collaborations between Alpine artisans and technologists, emphasizing that innovation and tradition are not mutually exclusive.

The Spirit of Place in the Contemporary Imagination

Across all these forms—architecture, land art, film, installation—the sense of place remains central. The Alps are not a backdrop; they are a co-author. Artists respond to the altitude, the materials, the history embedded in stone and trail. This is art that listens to its setting and asks what it means to be Alpine today—not just in heritage, but in outlook.

Conclusion: Continuity and Renewal in Alpine Art

The art of the Alps is not merely a regional story. It is a testament to the way place shapes expression, how landscape, material, and tradition form a visual culture that endures through time while continually evolving. From prehistoric carvings and Roman mosaics to Baroque altarpieces and modern architectural minimalism, Alpine art has always reflected the balance between permanence and change, nature and human ingenuity.

What distinguishes the art history of the Alps is not a single school or doctrine, but a set of enduring values: craftsmanship, clarity, practicality, and a strong sense of belonging to the land. Across centuries, Alpine artists have responded not only to broader European movements—Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Romanticism, Modernism—but have interpreted them through the lens of local materials, religious life, seasonal rhythms, and community needs.

Even in periods of great upheaval—war, reformation, industrialization, or globalization—the visual culture of the Alps has shown resilience. Its sacred art endured when politics shifted. Its vernacular craft survived modernization. Its painters and architects continued to shape space and image with a fidelity to place and purpose. And in today’s era of environmental uncertainty and cultural homogenization, the Alps remain a unique model of how art can stay rooted while engaging with the present.

There is also a continuous interplay between tradition and reinterpretation. From folk carvings and painted houses to avant-garde sculpture in alpine meadows, the visual history of the Alps invites both preservation and transformation. This is not a static heritage but a living one, passed down through families, workshops, schools, and now digital platforms. Its artists may work with drone footage, recycled wood, or augmented reality—but they are drawing from the same well as the anonymous stonecutters of Romanesque cloisters or the Rococo stuccoists of Tyrol.

Ultimately, the art of the Alps is not just about mountains. It is about how people live within them, how they mark time, construct meaning, and preserve memory. It is a record of faith, identity, and endurance—and a quiet assertion that beauty, properly understood, can emerge from modest forms, difficult conditions, and enduring ties to the land.

As visitors, historians, and locals alike continue to engage with this art, they participate in its renewal. Whether in a weathered roadside shrine, a contemporary mountain gallery, or a centuries-old village fresco, the Alps speak—and their art, shaped by stone, sky, and centuries, continues to answer.