The oldest known artworks in Texas are not in museums or private collections. They are etched and painted into the land itself—hidden in canyons, under ledges, and across the sun-bleached walls of remote river basins. These are not simply remnants of prehistoric life. They are declarations of belief, memory, and ritual left by peoples whose names we no longer know, but whose vision remains indelibly fixed on the rock.

Tracking Time in the Pecos Canyonlands

Nowhere is this visual legacy more complex or more mysterious than in the Lower Pecos region, where the Rio Grande carves through layered sandstone and limestone to form steep-walled canyons along the Texas-Mexico border. Here, in sites such as Panther Cave, White Shaman, and Halo Shelter, archaeologists have documented thousands of pictographs—multi-colored wall paintings dating back at least 4,000 years, some possibly older. Painted with natural pigments made from ground minerals, animal fat, and plant binders, these compositions form a coherent yet elusive visual system: repeating motifs of antlered figures, serpents, hunting scenes, and composite human-animal forms.

Despite decades of study, no consensus exists on the full meaning of these works. What is clear, however, is their complexity. These were not casual marks left in passing. The images are composed in overlapping layers, with repeated symbols and deliberate alignments. Some murals stretch over 60 feet across canyon walls, with human-like figures rendered at life size. Their scale, detail, and positioning suggest communal rituals—painted over generations to anchor ceremonies that combined storytelling, cosmology, and survival.

Shamans, Spirits, and the Language of Pigment

One prevailing interpretation, supported by scholars such as Carolyn Boyd, is that the Pecos River rock art reflects shamanistic belief systems, encoded in visual language. The elongated, often floating human figures with headdresses or antlers may represent shamans undergoing trance states or spiritual transformation. These artworks are thought to depict not only animals and people but spirit journeys and mythic episodes—cosmic narratives that played out both in the minds of the shamans and on the cliffs that surrounded their communities.

Several pictographs show human figures flanked by dotted lines or wrapped in serpentine forms—possibly visual analogs to the altered states induced by psychoactive plants like peyote, which is native to south Texas and northern Mexico. Some scholars argue that these visual sequences mimic the experience of entering otherworldly realms during trance. Whether or not these images were meant to be literal, their organization and rhythm suggest a form of storytelling more symbolic than illustrative.

Unlike rock carvings (petroglyphs), which are relatively common across the Southwest, the Pecos murals depend on paint—particularly red ochre, white kaolin, black charcoal, and yellow clay. Red, in particular, dominates the visual language, perhaps for practical reasons—its iron-rich pigment binds well to limestone—but also likely for symbolic ones. Blood, fire, sun, and life are obvious associations, but the true significance remains buried in cultural memory long since lost.

Why So Much Red? Symbolism and Survival

Red pigment turns up not only in the Lower Pecos but across early Texas rock art. In Hueco Tanks, near El Paso, red is used in complex geometric symbols possibly tied to Jornada Mogollon ceremonialism. In the Devils River and Trans-Pecos regions, red-painted shields, dots, and animal tracks appear in caves and shelters. Even in the arid Big Bend, red emerges as a dominant visual constant.

Why red? The answer may lie partly in geography—red ochre sources were plentiful, easy to process, and durable. But survival, too, depended on visibility. Red paintings withstand weather better than others and stand out vividly in the glare of desert light. In an unforgiving landscape, art was never idle—it had to endure, warn, mark, or bless. These were images meant to be seen across generations. Perhaps red survived because its meaning demanded it.

Three especially compelling sites reflect this visual grammar:

- White Shaman Mural, near Seminole Canyon: a 24-foot tableau of hunting, ritual figures, and possible star maps, painted in red, white, and black.

- Panther Cave, named for its leaping red feline figure, possibly a jaguar—a powerful symbol in Mesoamerican and Southwestern mythologies.

- Rattlesnake Canyon, where a long sinuous red form wraps around a rock face, possibly representing a mythic snake or water deity.

Each of these sites presents a worldview as much as an artwork. They suggest that, for these ancient people, image and place were inseparable.

The images were also social. Many are located in acoustically resonant shelters, suggesting performance—chanting, dancing, or drumming that echoed off painted walls. In this way, the rock became not just a canvas but a resonating chamber for cultural transmission. Art, sound, memory, and land fused into a single sensory experience.

The mystery of Texas rock art lies not in what we don’t know, but in how much survives without explanation. These are the oldest known artworks in Texas, but they are also some of its most layered, deliberate, and enduring. When Spanish missionaries arrived in the 18th century, they often dismissed such images as pagan superstition. But to the people who made them, these were sacred sites, repositories of meaning shaped by wind, pigment, and faith.

Though unspoken, the canyons still speak.

Ceramics and Patterned Earth: Art of the Early Agricultural Peoples

Before written language, before metallurgy, before the horse ever set hoof in North America, the early agricultural peoples of what is now East Texas and the southern Plains created objects of remarkable subtlety—painted, incised, coiled, and fired into permanence. Their art survives not in vast murals or monumental ruins, but in clay vessels, burial mounds, and the geometry of land altered by cultivation and ceremony. Among these peoples, particularly the Caddo, artistic labor was inseparable from community structure, seasonal cycles, and the demands of a humid, wooded landscape.

Caddo Clay and the Geometry of Fire

By around 800 AD, the ancestors of the Caddo Nation had developed a sophisticated pottery tradition in the lush forests and river valleys of East Texas, western Louisiana, and southeastern Oklahoma. These communities—descended from earlier Woodland and Mississippian cultures—built ceremonial mounds, practiced maize agriculture, and left behind thousands of vessels whose elegance rivals that of more widely recognized ancient civilizations.

Caddo ceramics were both functional and sacred. Burial urns, effigy vessels, and food storage containers were meticulously formed using coil-and-scrape techniques, then decorated with finely incised or engraved patterns: concentric spirals, herringbone motifs, crosshatching, and stylized birds or hands. Unlike the rugged utilitarian wares of nomadic groups, Caddo pottery often exhibited perfect symmetry and deliberate polish. Many were blackened through reduction firing, producing a rich charcoal sheen that gave the surface depth and visual complexity.

These forms were not merely containers but communicative objects. Scholars believe that certain motifs held clan or lineage significance, and some designs seem to mark ceremonial status. The placement of pottery in burials—often alongside shell ornaments, pipes, and woven fabrics—suggests that aesthetic refinement was closely tied to social identity and belief systems. Art did not exist in isolation; it was interwoven with subsistence, ritual, and diplomacy.

Archaeological finds such as those at the George C. Davis Site near present-day Cherokee County demonstrate how highly standardized and specialized these ceramic forms were. The scale of production and consistency of design imply centralized craftsmanship, perhaps by designated artisans working under elite patronage or religious leadership. The geometry of the pottery mirrored the geometry of social structure.

Visual Order on the Southern Plains

While the Caddo offer the clearest ceramic legacy, other early agricultural peoples across Texas—particularly those in the Panhandle and South Plains—developed distinct visual vocabularies rooted in their environments. Among the Plains Village cultures (active roughly 1000–1500 AD), pottery was plainer but still purposeful: globular jars and bowls, often cord-marked or incised, used for cooking and storage in semi-permanent villages along rivers like the Canadian and Brazos.

Unlike the dense woodland cultures of East Texas, Plains artists had to contend with wind-swept flatlands, erratic rainfall, and buffalo migrations. Their art reflects this mobility. Decorative objects tended to be portable: carved bone tools, incised stone disks, shell pendants, and painted hides. Some evidence suggests long-distance trade with the Southwest and even Mesoamerica, as seen in occasional copper or turquoise fragments found in burial contexts.

One intriguing regional phenomenon is the antler carving tradition of the Southern Plains. Tools, toggles, and ritual items were often shaped into stylized zoomorphic or geometric forms. These are not decorative in the modern sense—they were deeply practical—but they suggest a tactile visual culture, one in which the artist’s hand was guided by both function and symbol.

Also notable is the ceremonial use of earth itself. Archaeological surveys in the Panhandle reveal deliberately shaped platforms, possible ritual enclosures, and buried offerings—patterned arrangements that used dirt, stone, and ash as aesthetic media. In these works, the line between sculpture and architecture vanishes.

Trade, Migration, and the Spread of Style

What unified these disparate traditions was not a single culture or empire, but movement. Across the centuries preceding European contact, Texas sat at a crossroads of migration and trade, where the artistic influence of the Mississippian mound-builders met the Puebloan cultures of the Southwest and the hunter-gatherer bands of the Gulf Coast. Ceramics, shell ornaments, pigments, and even iconographic styles moved across vast distances by foot and canoe.

This movement is visible in hybrid objects. Some Caddo pottery forms, for example, incorporate Southwestern-style rim flanges or curvilinear motifs resembling Pueblo designs. Similarly, occasional engraved stones found in Central Texas show design logic more typical of southeastern ceremonial complexes—evidence of either trade, travel, or cultural diffusion. These aren’t the products of conquest but of contact, where style became a soft kind of diplomacy.

Three examples speak to this interplay:

- A Caddo effigy bottle from the early 13th century, shaped into the form of a horned serpent—likely a spiritual figure shared with Mississippian mythology.

- A burial cache near present-day Nacogdoches containing shells from the Gulf Coast, turquoise from the Southwest, and obsidian sourced from over 500 miles away.

- A ceremonial mound complex in Titus County aligned with solstice markers, echoing cosmological orientations seen in distant mound-building societies.

Such finds suggest that ancient Texas was never provincial. It was a porous and interconnected space, with artistic ideas spreading along the same routes as salt, maize, and stories.

The significance of this early art lies not only in what it shows but in how it was made and used: slowly, deliberately, and always with an eye toward social order. Whether in clay, bone, shell, or dirt, the visual cultures of early agricultural Texas reveal communities deeply attuned to season, symmetry, and the sacred geometry of their landscape.

Theirs was a world of continuity—art as ritual, ritual as memory, memory as form.

Contact and Collision: Spanish Colonial Aesthetics in Mission Texas

In the 18th century, a different kind of image arrived in Texas—one shaped not by earth and fire, but by empire, evangelism, and European art history. With the spread of Spanish colonialism northward from Mexico, a wave of religious imagery transformed the visual landscape. What had once been a region of clay vessels, painted canyons, and carved bone became a theater of gilded altars, frescoed chapels, and imported saints. But this transformation was neither total nor uncontested. Texas mission art is not a clean overlay of Catholic iconography on an empty canvas—it is a record of collision, adaptation, and resistance, painted in limewash and blood, carved by hands both native and foreign.

Frescoes in the Chapel Dust

By the early 1700s, Spanish friars and soldiers had established a chain of missions stretching from El Paso to Goliad, with the San Antonio complex as their cultural and administrative hub. These missions were not simply churches. They were fortified compounds: centers of forced labor, conversion, and agrarian control. Indigenous groups—Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa, and others—were baptized, settled, and made to work under the guise of salvation. With this came an avalanche of visual language: crucifixes, retablos, saints, monstrances, and fresco cycles.

One of the most remarkable visual survivals from this period is the wall painting at Mission Concepción in San Antonio. Though weathered and incomplete, it remains the oldest unrestored church fresco in the United States. The walls and vaulted ceilings are decorated with ochre-red, blue, and yellow vegetal patterns, false architectural trompe l’oeil, and stylized sunbursts—a blend of Spanish Baroque exuberance and local adaptation. These works were likely completed by mestizo artisans trained in Mexican religious painting traditions, using lime-based plaster and natural pigments.

The result is both familiar and strange: Christian symbols rendered with unexpected flair, foliage resembling indigenous motifs, and color schemes influenced more by the deserts of Chihuahua than the chapels of Castile. Elsewhere, at Mission San José, fragments of painted geometric borders and vegetal flourishes persist, hinting at a once-dazzling decorative program meant to awe the newly converted.

But even in these official spaces, the visual culture was never entirely Spanish. Archaeological evidence from mission sites reveals indigenous touches—bones carved with spiral or animal motifs, small devotional items combining Catholic and native imagery, and graffiti that undermines the hierarchy of the sacred. These fragments suggest a parallel aesthetic economy, operating beneath the watchful gaze of the friars.

Sacred Forms, Forced Conversions

Religious art was not a neutral gift—it was a tool of psychological conquest. The image of Christ crucified, the Virgin crowned, and the saints triumphant were designed to overwrite the visual cosmologies of native groups, replacing ancestral spirits and landscape deities with an unfamiliar pantheon of saints and martyrs. Retablos—elaborate altarpieces painted on wood or tin—became central to this strategy. Even small missions often featured hand-painted retablos or imported prints from Mexico City, depicting St. Francis, the Archangel Michael, or Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The Guadalupe image held special power. Though born of colonial syncretism in 16th-century Mexico, she came to represent a softer side of conversion. In Texas, she appears in altar carvings and personal objects, her brown skin and native features making her a bridge figure between cultures. Yet her presence was double-edged: a symbol of cultural fusion, but also of domination.

Even more ambivalent were the crucifixes found in mission churches—often grotesquely graphic, emphasizing the wounds and blood of Christ in ways foreign to indigenous aesthetic traditions. These images could inspire awe, but also revulsion or confusion. In some cases, native artisans were ordered to carve these figures themselves, resulting in startling hybrids: Christs with almond-shaped eyes, local plant species carved into the cross, or stylized sun rays evoking pre-Christian cosmologies.

Three recurring aesthetic tensions define this period:

- The spatial collision of indigenous settlement patterns with mission architectural grids, producing towns whose layout disrupted native social orders.

- The symbolic layering of Catholic icons over sacred sites—springs, caves, or burial grounds—once central to native religious life.

- The material dissonance between European religious art (gold leaf, linen, oil paint) and the local materials artisans actually had: clay, bone, pigment, and adobe.

Through these contradictions, the aesthetic landscape of Texas became something new—neither fully Spanish nor indigenous, but something unstable, negotiated, and alive.

Hybrid Imagery: Indigenous Hands, European Eyes

Over time, a third visual mode emerged—hybrid art, shaped by native labor, Catholic oversight, and mestizo mediation. In some missions, indigenous artisans began producing devotional art that subtly encoded native meanings beneath Catholic forms. A clay statue of St. Anthony might carry the posture of a native rain spirit. A painted angel’s wings might resemble eagle feathers worn in local dances. Scholars of visual syncretism have documented dozens of such instances—small deviations that suggest resistance and continuity masked as obedience.

One poignant example is the painted gourd rattles recovered from burial contexts near former mission grounds. While these rattles were clearly used in Christianized funerary rites, their decoration includes motifs not found in European liturgical art: spirals, thunderbirds, and celestial symbols common in indigenous cosmologies. These were not errors or misinterpretations—they were acts of quiet endurance.

In borderlands like Texas, hybridity was not an exception but a strategy. Art became a medium for expressing belief, submission, skepticism, and coded defiance all at once. For every crucifix that demanded conversion, there was a hand-painted bowl or carved spindle carrying a language the friars could not read.

Even centuries later, traces of this visual conflict remain. The mission churches still stand, weathered and restored, their murals and carvings offering a palimpsest of colonial ambition and native resilience. But beneath their surfaces—sometimes quite literally—lie older marks: ghost traces of erased figures, overpainted symbols, hidden geometries.

If the early agriculturalists left art tied to the land, and the Spaniards brought images tied to heaven, then the mission period marks a painful and ongoing attempt to stitch the two together—never fully succeeding, but never entirely failing either.

Icons on the Frontier: 19th-Century Religious and Vernacular Art

On the Texas frontier, art was not a profession—it was a survival instinct, a devotional impulse, a way to make sense of a world defined by violence, distance, and hard-won beauty. In the 19th century, as Texas passed from Spanish to Mexican to independent and finally American control, its visual culture fractured and diversified. In missions and cabins, cemeteries and churches, cow camps and border towns, a rough but deeply personal aesthetic took hold. It was not the polished art of academies or galleries. It was hand-hewn, improvised, and often anonymous—art made from scraps and faith, with as much urgency as reverence.

Madonnas and Mustangs

After the secularization of the Spanish missions in the early 1800s, religious art in Texas did not disappear—it migrated. What had once been maintained by friars and church hierarchies passed into the hands of ordinary people. Mexican Catholic families in South and Central Texas kept household retablos—small painted panels of saints and holy figures—on mantels, shelves, and bedroom altars. These were often homemade or purchased from itinerant artists who painted on tin, copper, or discarded wood.

Some were carefully copied from church-approved iconography. Others veered into the personal and regional. In one notable 1840s example, the Virgin Mary appears with a mustang at her feet—a blend of Marian devotion and frontier life, likely meant to link the sacred with the daily struggles of ranching and survival. These weren’t art-for-art’s-sake objects. They were protective, even transactional—offerings made in the hope of safe childbirth, protection from Comanche raids, recovery from fever, or successful harvests.

Though influenced by Mexican folk art traditions, Texas retablos developed a distinct character. Saints often wore clothing more suited to rural Texas than to Judea or Rome. Colors were bold but limited, based on what pigments or house paints were available. Proportions could be awkward, gestures stiff, but the emotional sincerity was never in doubt.

At the same time, Anglo settlers arriving from the American South brought their own forms of vernacular religious art: carved wooden crosses, painted tombstones, and domestic embroidery stitched with biblical verses. The fusion of these worlds—Mexican Catholic, Anglo Protestant, and indigenous—produced a rough pluralism where sacred imagery was as likely to appear in a cornfield shrine as in a formal church.

Painted Furniture, Personal Devotions

Religious imagery was not limited to paintings or sculpture. Furniture became a key site of artistic expression, especially in communities with limited access to imported goods. Across 19th-century Texas, one finds hand-painted trunks, cabinets, and chairs, often adorned with floral patterns, stylized birds, crosses, or family initials. German, Czech, and Polish immigrants in the Hill Country contributed richly to this tradition, bringing with them Central European folk motifs and adapting them to local materials.

In the rural towns of Fayette, Lavaca, and Karnes counties, immigrant families decorated their homes with painted altars and small wooden shrines, often built into niches or corners of kitchens. These were places of private prayer but also served as visual records of lineage and belief. In some cases, painted furniture was created as part of marriage customs or dowries, with religious symbols entwined with family heraldry and floral design.

Such artifacts blur the line between art and utility. A flour bin might double as a devotional altar. A bench might be painted with images of lambs and crosses, to be used in both domestic life and mourning. Nothing was wasted—materially or symbolically.

Equally important were textiles. Quilts, samplers, and altar cloths embroidered with biblical verses or saintly images became a kind of soft iconography. These were portable, intimate, and tactile objects—used, touched, and worn. They were not hung on gallery walls, but folded into daily life.

Three common visual elements recur across vernacular frontier art:

- Hearts aflame, a motif shared by Catholic Sacred Heart imagery and Protestant revivalist visual culture.

- Sunbursts and stars, used to represent divine presence or celestial protection, often painted onto furniture or ceiling beams.

- Crossed tools, such as axes or plows beneath a cross, symbolizing labor sanctified by faith.

These recurring forms reflect a spirituality tied to the land—faith expressed not in ecclesiastical architecture but in the rhythms of rural toil.

Craft as Survival on the Borderlands

Art on the Texas frontier was also a form of endurance. For Black Texans, freed or enslaved, visual creativity was often embedded in craft traditions. Grave markers made of hand-chiseled stone, quilts assembled from cast-off clothing, and wood carvings hidden in cabins served as cultural anchors in a world defined by displacement and marginalization.

In South Texas, Tejano artisans—descendants of Spanish, Mexican, and indigenous peoples—maintained a hybrid tradition of religious woodcarving and adobe ornamentation. Some of these works, especially painted santos (saints), show remarkable stylistic consistency across generations, despite political upheavals and material scarcity.

Meanwhile, Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache artists on the Plains continued to produce painted hides, beaded garments, and carved pipe stems well into the late 19th century, even as they were driven onto reservations or hunted by Texas Rangers. These works—portable, personal, and sacred—often contained narrative imagery: depictions of battles, visions, or animal spirits. Though rarely preserved by museums at the time, these pieces offer an essential counter-narrative to the frontier mythos—a visual record of resistance and survival amid state violence.

A poignant example is the ledger art produced by Plains warriors imprisoned at Fort Marion in Florida in the 1870s. Though not created in Texas, many of the artists—like Howling Wolf and Bear’s Heart—had been captured in Texas and painted scenes from their lives in Indian Territory. Using pencils and crayons on accounting paper, they rendered battles, rituals, and hunts in a style both traditional and radically adapted to confinement. Their work marks the end of one era of indigenous art in Texas—and the beginning of another, shaped by dispossession.

By the end of the 19th century, Texas was no longer a frontier in name. The railroad, the courthouse, and the oil derrick had begun to displace the chapel, the ranch, and the border fort. But the art left behind in this transitional period—faint on tin, carved into trunks, stitched into quilts—offers a visual memory more honest than any history book.

It tells us who prayed, who mourned, and who survived.

Cowboys, Cameras, and the Rise of the Mythic West

By the late 19th century, Texas was no longer a contested borderland but a stage—one where image and identity began to merge in unprecedented ways. The expansion of railroads, the rise of print culture, and the mass production of photographic equipment helped transform Texas from a lived geography into a powerful and exportable fiction. It was during this period that the state became mythic—its visual identity increasingly shaped not just by local art but by the way it was framed, printed, staged, and sold to outsiders. Art was no longer only devotional or functional. It became performative, promotional, and steeped in spectacle.

Longhorns, Landscapes, and Lithographs

As Texas settled into statehood and began to project power outward—economically, militarily, and symbolically—its artists turned to landscape as a means of expressing both grandeur and ownership. Following in the wake of the Hudson River School and its Americanist romanticism, Texas painters began to depict their state as a land of sublime promise: vast plains, distant mountains, stormy skies, and monumental herds of longhorn cattle.

Among the best-known practitioners of this approach was Julian Onderdonk, often called the “father of Texas painting,” though his prominence came slightly later in the early 20th century. In the late 19th century, it was his father, Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, who helped introduce academic art traditions to the region, co-founding the Art Students League of Dallas and promoting realism through landscapes and history painting.

But beyond the easel, it was the lithograph that carried Texas imagery across the nation. Commercial artists working for railroads, land companies, and immigration agencies created vivid prints of Texan vistas, ranches, and towns, designed to attract settlers and investors. These works often exaggerated scale and abundance: golden wheat fields stretching to the horizon, spotless train stations under vast blue skies, and idyllic ranch homes surrounded by docile cattle.

Three features defined this style of commercial frontier art:

- Exaggerated scale—landscapes stretched impossibly wide to convey abundance.

- Idealized figures—cowboys appeared noble, calm, and whitewashed of hardship.

- Absent conflict—native presence was erased or stylized into harmless nostalgia.

This was not art as personal expression but as economic tool: a visual seduction for those who had never set foot in Texas, selling a future in oil, land, or cattle. It helped fix in the American mind a vision of Texas that endures in diluted form even now.

Photographers of the Open Range

If the lithograph idealized, the photograph complicated. By the 1870s and 1880s, portable cameras had become common enough for professional photographers to set up studios in Texas towns, ride with cattle drives, or embed with military units. Their work documents not just the myth but the texture of life on the frontier—the grit behind the legend.

One of the most important early figures was Erwin E. Smith, a young photographer born in 1886 in Honey Grove, Texas. Smith spent the first years of the 20th century photographing ranch life across West Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Unlike many who staged or romanticized cowboy life, Smith worked with intimacy and respect. His images of branding, chuckwagon cooking, trail riding, and bunkhouse rest depict the hard, dirty, often monotonous work of cattle ranching.

What’s remarkable in Smith’s work is the human scale. Cowboys are not silhouetted against dramatic skies but caught mid-task—bending to mend a stirrup, smoking beside a post, dozing beside their dog. These images pushed back against both the dime novel’s fantasy and the tourist’s caricature, revealing the West as lived, not merely imagined.

Other photographers—like W.D. Smithers, who documented South Texas border life, or R.H. Talley, known for portraits of townspeople and early oil fields—contributed to a growing archive of Texan reality. Their work captured the ethnic and economic diversity that the myth often ignored: Tejano ranchers, Black cowhands, German settlers, and women operating businesses or running households in austere conditions.

Yet photography was not neutral. Studios often perpetuated romantic tropes, dressing sitters in borrowed cowboy gear or posing them beside fake campfires. Native people, especially Lipan Apache and Comanche subjects, were frequently photographed under duress or as anthropological curiosities—dignified in bearing, but stripped of agency.

Still, the camera did something painting and printmaking rarely could: it documented contradiction. In a single album, one might find a serene landscape beside a lynching photo, a wedding portrait beside a chain gang. Photography gave Texas an uneasy visual archive—a mirror of its promises and its cruelties.

The Selling of Texas Identity

By the turn of the century, Texas had become a cultural brand, and its artists—wittingly or not—became its marketers. World’s fairs, postcards, magazine illustrations, and early cinema helped broadcast a particular image of the state: masculine, open, untamed, and profitable. Cowboys and oilmen, longhorns and tumbleweeds, missions and wide skies—these became the shorthand, reproduced endlessly, often without regard for historical complexity.

In some ways, this visual branding served Texans themselves. It gave form to state pride and offered a counterweight to coastal elitism. But it also smoothed over fractures—racial violence, labor struggle, environmental degradation—and enshrined a narrow version of Texan identity centered on Anglo masculinity and land ownership.

One striking example is the depiction of the Texas Ranger in art and popular culture. Often shown as heroic and stoic—rifle in hand, hat low—Rangers became icons of order. In paintings, illustrations, and early film, they were the guardians of law in a wild land. But missing from these images were the extrajudicial killings, the surveillance of Mexican communities, and the suppression of Tejano political movements that formed part of their actual history.

In this period, art began to serve two masters: document and myth. Some artists sought to capture the changing state with fidelity and subtlety. Others—often more commercially successful—pandered to fantasy. The resulting legacy is conflicted. Much of what we now think of as “classic Texas art” is neither false nor true—it is curated, chosen, and performed.

But it left behind a powerful visual record: one that shaped both how Texas was seen and how it came to see itself.

Academic Painting and the Cult of Texas Exceptionalism

By the early 20th century, Texas art had begun to move indoors. Landscapes that had once been lived and photographed were now interpreted from within studios, academies, and museums. As Texas grew wealthier and more politically influential, a visual culture emerged to match its ambitions: grand in scale, historic in theme, and rooted in a self-conscious narrative of exceptionalism. The art of this period was not only about beauty or technique. It became a visual argument—one that positioned Texas as morally singular, mythically important, and historically inevitable.

The Birth of Regional Art Institutions

The infrastructure for this new mode of art began with patronage and professionalization. Between 1900 and 1930, major cities such as Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio established museums, art societies, and university departments dedicated to the cultivation of “fine art.” These institutions—often founded or supported by oil money, railroad wealth, and real estate speculation—sought to anchor Texas culture within the larger framework of American art while also promoting a distinct regional style.

The Dallas Art Association, founded in 1903, was among the first of these. By 1936 it would become the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, one of the few Southern institutions collecting both European and American works. In Fort Worth, the Carnegie Library hosted early exhibitions of academic painting, which helped establish a community of formally trained artists. Meanwhile, the San Antonio Art League, founded in 1912, became a stronghold for a more rustic, landscape-focused tradition, one that celebrated local scenery over continental theory.

Art schools followed close behind. The Museum School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the University of Texas at Austin’s Department of Art formalized instruction, bringing in professors trained in Europe or the East Coast. Academic realism—anchored in drawing, perspective, and classical subject matter—dominated curricula. By the 1920s, Texas had a generation of artists who were both regionally committed and professionally credentialed.

This wave of institutional support coincided with a growing desire to see Texas reflected in large-scale, authoritative ways. Enter the history painter.

Bluebonnets, Battlefields, and Bronze

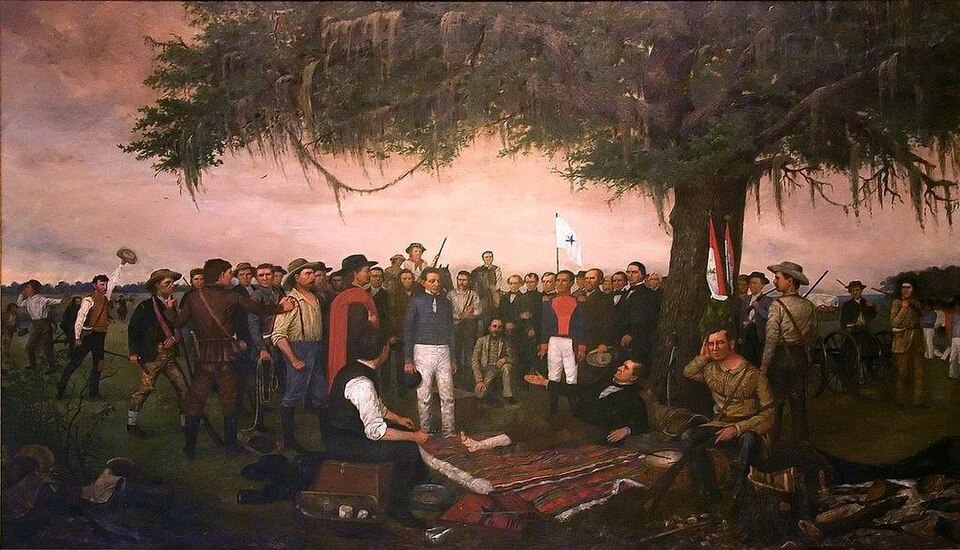

The most celebrated and revealing form of Texas academic art in the early 20th century was the historical tableau—paintings that told stories of the Alamo, the Battle of San Jacinto, frontier heroism, and pioneer virtue. These works echoed the grand manner of European salon painting but substituted aristocrats and emperors with Texian rebels, cowboys, and settlers.

One of the most influential painters of this mode was Harry Anthony DeYoung, who chronicled early Texas battles and rural life with theatrical flair. Another was Tom Lea, who balanced documentary accuracy with stylistic bravado in his murals and narrative paintings. At the San Jacinto Monument and other civic landmarks, their work turned military episodes into secular scripture. The Texas Centennial Exposition of 1936 in Dallas marked the high point of this mode: a state-sponsored aesthetic parade of murals, bronzes, and bas-reliefs devoted to glorifying Texas history.

But the century’s most ubiquitous visual motif was arguably the bluebonnet. Texas wildflowers, particularly bluebonnets, became shorthand for a kind of idealized femininity and rural grace. Artists like Julian Onderdonk (whose career blossomed just before World War I) and his sister Eleanor Onderdonk rendered fields of wildflowers with an atmospheric glow that blended Impressionist technique with local subject matter. These works sold widely, were reproduced in calendars and advertisements, and helped popularize the idea of Texas as a place of delicate natural beauty rather than raw frontier violence.

The bluebonnet became more than a flower—it became a code for identity: genteel, grounded, and unthreatening. Its popularity reveals a subtle anxiety underlying the period’s art. As urbanization, oil development, and mass migration transformed Texas, artists turned increasingly to nostalgic scenes of log cabins, dusty trails, and flowering meadows. This was art as reassurance, not confrontation.

Bronze sculpture, too, played a major role. Courthouse lawns across the state began to fill with equestrian statues, war memorials, and busts of frontier icons. These were rarely abstract or ambiguous. They were declarative—meant to instruct, inspire, and sanctify. The Texas Ranger with his Winchester, the pioneer woman with her child, the Confederate soldier at parade rest: these figures were visual declarations of legitimacy, installed during a time of contested memory and rapid demographic change.

Art as Historical Pageant

At its most ambitious, academic painting in Texas became a form of pageantry—a visual performance of the state’s self-conception. Artists such as Porfirio Salinas and José Arpa brought refined techniques to regional landscapes, while others focused on dramatic compositions of historical events. But the collective aim was often the same: to fix Texas history into a permanent visual script.

This script was selective. It glorified the Alamo but omitted Tejano contributions. It celebrated the frontier but ignored the displacement of indigenous nations. It presented cotton fields without slavery, ranches without laborers, oil wells without ecological cost. In short, it flattened complexity in the service of pride.

Three recurring aesthetic strategies define this period:

- Heroic scale: oversized canvases and murals emphasized grandeur and inevitability.

- Moral clarity: subjects were painted with visual certainty—no ambiguity, no irony.

- Civic placement: art was installed in capitols, schools, post offices, and fairgrounds, reinforcing its authority through location.

One of the most potent examples is the series of New Deal-era murals commissioned for Texas post offices under the Section of Fine Arts. These murals, often painted by Texas artists, depicted regional history in bold, figurative styles: Native Americans in profile, Spanish explorers planting crosses, Anglo settlers plowing fields. Though federally funded, they echoed the same themes: struggle, conquest, and triumph, told from a narrow perspective.

What emerges from this period is a deeply revealing contradiction: a state obsessed with independence, but equally invested in state-sponsored art; a culture of rugged individualism, celebrated through collective myth; a resistance to outside influence, even as academic painting borrowed heavily from European traditions.

The legacy of Texas exceptionalism in visual art is both enduring and double-edged. On one hand, it fostered a strong, regionally rooted tradition that gave voice and shape to local history. On the other, it entrenched a vision of that history filtered through selective memory, institutional power, and visual idealization.

That vision would not go unchallenged for long.

Painted Churches and Immigrant Ornament: Central European Traditions in Texas

While Texas artists in cities were building academic traditions and mythic histories, a quieter but no less ambitious movement was taking place in rural towns and countryside chapels. Brought by Czech, German, Polish, and Moravian immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries, a flourishing tradition of religious ornamentation transformed modest wooden churches into visual sanctuaries of old-world memory. Known today as Texas’s “painted churches,” these structures reflect a transplanted aesthetic—rooted in European folk baroque and devotional practice—that thrived in new soil.

Ceilings Like Heaven: The Painted Church Phenomenon

Scattered across the rolling fields of Fayette, Lavaca, and Lee counties, these rural churches appear plain from the outside—white clapboard facades, modest steeples, simple towers. But step inside, and the walls explode into color, pattern, and painted illusion. Ceilings become starry vaults, columns are faux-marbleized, and wooden altars shimmer with gold leaf. Artists used common house paints and everyday brushes to create illusions of grandeur: arches where none exist, depth where there is only flat wall.

Among the most celebrated examples is St. Mary’s Church of the Assumption in Praha, where a deep blue apse is flecked with stenciled gold stars, and pillars are painted in trompe l’oeil marble. St. John the Baptist in Ammannsville features pink and lilac hues accented with roses and intricate border work. Nativity of Mary in High Hill, often called the “Queen of the Painted Churches,” contains elaborate stencil work, Gothic tracery, and symbols of the apostles tucked among floral bands.

These interiors were often the work of self-taught artisans or priests who had trained in Europe. Stencils, templates, and folk patterns circulated among immigrant communities, creating a shared yet varied visual language. The churches were not replicas of European cathedrals—they were interpretations, adapted to wood-frame construction and limited budgets. But their ambition was spiritual and cultural: to create a sense of sacred beauty in a new and uncertain world.

Stencils, Symbols, and Scriptural Decoration

The decorative vocabulary of the painted churches was drawn from multiple sources: Gothic revival motifs, Baroque ornament, regional folk patterns, and religious iconography. Rather than relying on imported sculpture or stained glass, communities embraced pattern painting—an art form that allowed for rich expression with humble tools.

Common decorative elements included:

- Stylized vines and roses, representing the Virgin Mary and the continuity of faith.

- Illusionistic columns and cornices, giving the impression of stone architecture.

- Biblical inscriptions in German, Czech, or Latin, often painted in ribbon-like banners across arches and friezes.

In many churches, artists used trompe l’oeil techniques to render architectural features that didn’t exist in the building’s structure: archways, alcoves, cornices, and keystones. These illusions were not deception, but aspiration—a way to elevate humble materials through craft.

Though each church is unique, the shared aesthetic reveals a community-wide value placed on visual reverence, spiritual permanence, and cultural memory. Even today, walking into these spaces feels less like entering a building and more like entering a mental landscape—one where faith and heritage are fused in floral borders and faux marble columns.

Craft, Continuity, and Devotional Identity

The painted church tradition is part of a broader phenomenon: the persistence of immigrant craft traditions in visual culture. Across Central Texas, one finds decorative grave markers, wooden crucifixes, embroidered altar cloths, and hand-painted stations of the cross—objects made not for public exhibition but for use, prayer, and remembrance.

In homes, too, these traditions persisted. Painted wooden furniture, wall hangings with scriptural verses, and carved religious figures adorned domestic interiors. These were not signs of nostalgia but of cultural continuity—evidence that faith, language, and craft could survive displacement.

Unlike the public art of cities or state institutions, immigrant religious art did not seek to define Texas identity for the world. It sought instead to define home. In doing so, it preserved a layer of artistic expression that is quieter but no less important: the art of belonging, of memory, and of devotion shaped in wood and paint.

Though often overlooked in surveys of Texas art, the painted churches and associated traditions represent one of the state’s most sustained and cohesive aesthetic movements. They remind us that artistic grandeur doesn’t always require marble, fresco, or capital funding. Sometimes it only requires a brush, a ladder, and the will to beautify a place where people gather to believe.

Murals, Movement, and Memory: Mexican-American and Chicano Art in Urban Texas

As the 20th century unfolded, the dominant images of Texas—bluebonnet landscapes, cowboy portraits, historic battles—began to fracture. In cities like San Antonio, Houston, El Paso, and Dallas, a new visual language emerged from the walls of neighborhoods, schoolyards, and community centers. Bold, saturated, and unapologetically political, this movement came not from museums or academic studios, but from street corners, union halls, and university protests. What became known as Chicano art was not simply a style—it was a cultural assertion, a visual reclamation of space, identity, and history by Mexican-American communities long excluded from official narratives.

Murals, Movement, and Neighborhood Walls

The mural—long a staple of Mexican visual culture—became the cornerstone of Chicano art in Texas. Drawing inspiration from Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, Texas artists adapted the form to new settings. Rather than state palaces or public institutions, their canvases were barrio walls, community centers, schools, and underpasses.

One of the earliest and most influential hubs was San Antonio, where artists began transforming walls into statements of identity and resistance in the 1970s. Collectives like Con Safo and Los Quemados rejected both the Anglo art establishment and folkloric stereotypes, producing murals that mixed Catholic iconography, pre-Columbian symbols, revolutionary leaders, and contemporary street scenes.

In Houston’s East End, artists painted sprawling compositions that intertwined Aztec cosmology with local history: Tejanos working refineries, farmworkers marching for rights, mothers holding both children and protest signs. El Paso, straddling the border, became a crucible for cross-cultural experimentation—where muralists blended American pop, Mexican religious art, and border surrealism into an aesthetic all its own.

A few defining features emerged across these city-wide visual landscapes:

- Layered iconography: Indigenous symbols, religious figures, and revolutionary heroes depicted in the same plane.

- Communal authorship: Murals often planned and painted collectively, with community input shaping the imagery.

- Site specificity: Works were tailored to the histories and struggles of particular neighborhoods, making them acts of both art and historical memory.

These murals were not meant for passive admiration. They were acts of presence—visual declarations that “we are here” and “our story matters.”

Spiritual Hybridity and Folk Catholicism

A recurring theme in Chicano and Mexican-American art in Texas is spiritual hybridity—the weaving together of Catholic, indigenous, and folk traditions into new visual forms. The result was a sacred vernacular that felt at once ancient and modern, devotional and defiant.

In many murals and prints, the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared as protector and protest figure, watching over neighborhoods while bearing marks of resistance—flames, fists, roses, or bullet holes. Santos (saints) were reimagined as migrants, elders, or children. The crucifixion might be shown on a dusty roadside, beneath telephone wires and border checkpoints.

Artists like César Martínez, Santa Barraza, and Carmen Lomas Garza used not only religious imagery but also the aesthetics of home altars, votive paintings, and retablos. Their work captured the intimate textures of Mexican-American spiritual life—kitchens doubling as shrines, dreams painted on tin, papel picado fluttering in church halls.

Garza’s paintings, for example, eschew overt protest but are no less radical: they depict ordinary family scenes—making tamales, visiting relatives, lighting candles—that assert cultural continuity and dignity in the face of erasure. In this way, art became a kind of devotional testimony, not to saints alone, but to ancestors, neighbors, and shared memory.

Spiritual hybridity also expressed itself through material. Artists used:

- Lowrider aesthetics—chrome, candy paint, and pinstriping—to create sacred spaces on wheels.

- Domestic craft—quilting, embroidery, papel picado—as high art statements.

- Found objects—bottle caps, rosaries, corn husks—woven into altarpieces and installations.

This fusion of the sacred and the everyday made Chicano art visceral, local, and tactile—a far cry from the clean lines and cool detachment of modernist formalism.

From Rasquachismo to Studio Practice

A key concept that emerged from this period was rasquachismo—a term reclaimed by Chicano artists to describe an aesthetic of resourcefulness, maximalism, and defiance. Originally a derogatory word implying cheapness or bad taste, rasquache came to mean the art of making beauty from what one has, of refusing polish in favor of excess, hybridity, and humor.

This approach influenced both muralists and studio artists. Installations exploded with color and texture. Paintings rejected the minimalist restraint of elite art schools in favor of narrative, emotion, and clutter. Rasquachismo turned the discarded into the sacred—tortilla presses as altars, lawn ornaments as monuments, yard signs as canvases.

Over time, Chicano and Mexican-American artists began to enter galleries and museums—not by abandoning their roots, but by refining and expanding them. Artists like Luis Jiménez, whose fiberglass sculptures of vaqueros, border agents, and devilish rodeo riders combined pop scale with folk menace, helped bring this visual language into institutional spaces.

Jiménez’s controversial piece “Border Crossing” (1989), showing a family in motion across the Rio Grande, became emblematic of this transitional moment: monumental, technically daring, and charged with political resonance. Museums began to take note—not always comfortably, but increasingly inevitably.

The entry of Chicano art into academic and institutional circuits did not dilute its power. Instead, it expanded its audience, introducing broader publics to a Texas art history that had always been there—but often on the margins.

As these artists moved between murals and museum walls, between neighborhood and nation, they carried with them a truth that shaped the next generations of Texas art: that identity is not given, but built—and that image is a form of resistance, reclamation, and ritual.

Postwar Texas Modernism: Oil Money Meets Abstract Form

In the wake of World War II, Texas entered a period of unprecedented economic growth, driven by oil, military expansion, and rapid urbanization. But the changes were not only industrial or demographic—they were aesthetic. By the 1950s and 1960s, a new generation of artists, critics, and collectors began pushing Texas art beyond regionalism and folk tradition toward something sharper, cooler, and more experimental. The result was a visual upheaval: Modernism arrived in Texas, not quietly, but on a tide of petro-capital and cultural ambition.

Rothko in Houston, Téllez in San Antonio

Perhaps the most defining moment in Texas modernism came not from a native-born artist but from a Russian-American painter who had never lived in the state. In 1971, the Rothko Chapel opened in Houston, a meditative octagonal space housing fourteen vast panels painted in deep, atmospheric tones by Mark Rothko. Commissioned by Dominique and John de Menil—French émigrés turned Houston art patrons—the chapel was part of a larger effort to import avant-garde and international modernism into Texas with intellectual seriousness.

The de Menils weren’t interested in cowboy murals or bluebonnets. They collected Surrealists, abstract expressionists, conceptualists, and postwar European painters. Through their patronage, Houston became a kind of southern satellite for the New York art world, with the Menil Collection (opened in 1987) serving as both museum and think tank for modern aesthetics and spiritual inquiry.

Meanwhile, in San Antonio, a quieter but no less vital strain of modernism took hold. Artists like César A. Martínez, Mel Casas, and Amado Peña began fusing formal experimentation with cultural specificity. While Casas—best known for his “Humanscape” series—engaged in pop parody and visual puns, Martínez explored portraiture with graphic minimalism, rendering Chicano identity through stark, flattened shapes and muted palettes. These artists were modernists not by mimicry but by invention—drawing from abstraction and conceptualism without abandoning context or political edge.

Elsewhere in the state, Forrest Bess, a reclusive visionary from Bay City, produced a body of work entirely detached from dominant art centers. His small, enigmatic canvases—rooted in personal symbology, mysticism, and bodily transformation—earned him praise from figures like Meyer Schapiro and Betty Parsons, even as he remained largely unknown in Texas during his lifetime.

The paradox of Texas modernism was this: it was both deeply provincial and radically global, nurtured by artists who challenged regional clichés and by patrons who used oil money to import intellectual capital.

Museums, Mavericks, and Modern Design

The institutional infrastructure of Texas modernism developed rapidly between 1950 and 1980. In addition to the Menil Collection, other museums repositioned themselves as serious players in the postwar art world. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, under directors like William C. Agee, began acquiring abstract expressionism and post-painterly abstraction. The Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts, founded in 1957, explicitly championed avant-garde work before merging into the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1963.

In Fort Worth, the Amon Carter Museum and later the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth began collecting not just cowboy art but contemporary American painting, sculpture, and photography. Thanks to ambitious directors and deep-pocketed trustees, Texas museums became major clients for international artists—commissioning, acquiring, and exhibiting on a scale once unimaginable for a state still seen by some as cultural hinterland.

Meanwhile, the state’s universities became laboratories of visual innovation. At UT Austin, Texas Tech, and UNT Denton, art departments attracted both promising students and radical faculty. Minimalism, color field painting, kinetic sculpture, and experimental film all found adherents on Texas campuses.

Texas’s architectural scene echoed these shifts. Inspired by modernist design principles, museums and cultural centers embraced clean lines, exposed materials, and spatial austerity. Architect Philip Johnson’s Amon Carter Museum building (1961) and Renzo Piano’s design for the Menil Collection (1987) reflect not just global taste, but the desire to project cultural legitimacy through modern form.

Three elements defined this new institutional modernism:

- Corporate and philanthropic backing, especially from oil, banking, and insurance fortunes.

- International dialogue, with artists and curators traveling between Texas and New York, Paris, and Mexico City.

- Aesthetic pluralism, allowing conceptual, minimal, and figurative work to coexist in the same collections.

This was not grassroots modernism—it was strategic and well-funded, shaped by elites with cosmopolitan aspirations. But within this structure, space opened up for maverick voices and regionally grounded experiments.

Oil Booms, Patronage, and Power

None of this would have been possible without oil money. The postwar boom produced billionaires, and many of them turned to art as both cultural investment and civic legacy. The Schlumberger, Moody, Cullen, and de Menil families underwrote museums, galleries, acquisitions, and publications. Oil allowed Texas to leap over stages of cultural development—buying Rothkos, Giacomettis, and Warhols while much of the country was still debating abstract art’s legitimacy.

But patronage had its limits. The same institutions that championed global modernism often excluded local or nonconforming artists. Women, rural artists, and those working outside dominant formal languages struggled to gain visibility. For every internationally lauded installation, there were dozens of innovative Texas artists showing in co-ops, university galleries, or not at all.

And oil money brought with it a complex moral question. Could cultural refinement erase the violence and volatility of the resource economy that funded it? Artists like Terry Allen, based in Lubbock, answered with biting irony and conceptual rigor. Allen’s multimedia works—rooted in West Texas vernacular, honky-tonk surrealism, and postmodern wit—refused to flatter either side of the cultural divide. His art embodied the contradictions of the moment: provincial yet worldly, skeptical yet ambitious, regional yet never reducible to stereotype.

By the 1980s, Texas modernism had matured—but also fractured. Some artists embraced postmodern irony, others doubled down on formal purity, and still others turned toward identity, memory, and narrative. But the infrastructure built during this era—the collections, institutions, and public spaces—remained. They made it possible to imagine a future where Texas art didn’t need to justify itself to the coasts.

It could speak in its own terms.

Land, Light, and Isolation: The Marfa Effect

In a state where art had long been associated with mythic scale—oil barons, wide skies, grand narratives—the rise of Marfa offered something starkly different: minimalism, silence, and the uncanny clarity of desert space. What began as a remote military outpost in West Texas became, by the late 20th century, one of the most improbable and influential centers of contemporary art in the United States. At the center of this transformation stood Donald Judd, a New York sculptor who came to Marfa in the 1970s and never fully left—except in body.

Judd’s vision wasn’t merely to install art in the desert. It was to rethink the conditions under which art could exist—its relationship to land, architecture, time, and attention. In doing so, he created a cultural phenomenon now known simply as “Marfa”—a word that no longer refers only to a town, but to an aesthetic, a pilgrimage, a problem.

Donald Judd and the Reinvention of Space

Donald Judd first visited Marfa in 1971, drawn by the emptiness, the dry light, and the space—literal and conceptual—that the region offered. By 1979, he had purchased the decommissioned Fort D.A. Russell, along with buildings throughout the town, intending to create something radically different from the white cubes and temporary installations of the New York gallery scene.

Judd, a key figure in American minimalism, rejected the term “sculpture” for his work. His “boxes,” “progressions,” and “specific objects”—constructed from aluminum, concrete, or Plexiglas—were not meant to represent anything. They were objects in space, to be encountered, not interpreted. For Judd, Marfa offered the opportunity to install these works permanently, with control over light, distance, and orientation—conditions impossible in traditional museums.

At Chinati Foundation, established in 1986 on 340 acres of the old military base, Judd created what might be called the anti-museum. Instead of rotating exhibitions, Chinati presents permanent installations: Judd’s own 100 aluminum works housed in two artillery sheds, Dan Flavin’s fluorescent light installations in converted barracks, John Chamberlain’s crumpled-car sculptures, and later works by Roni Horn, Ilya Kabakov, and others.

The point was not diversity but depth. Visitors were invited to engage with a few works over hours or even days, in silence, in situ. Judd wrote extensively about space, proportion, and the ethics of art’s presentation, insisting that the setting was not neutral but integral. “The installation of my work and that of others is as important as the work itself,” he wrote. “It includes the space and the whole building.”

This idea—that art must be experienced in a fixed, permanent, and specific way—was revolutionary in a culture of spectacle and turnover. Marfa became the most enduring argument for site-specific minimalism in America.

Desert Geometry, Minimal Scale

Judd’s Marfa was not just about his own work. It was a conceptual intervention into architecture, urban planning, and art’s relationship to land. He purchased and restored multiple buildings in downtown Marfa, converting them into studios, libraries, living spaces, and exhibition halls. He worked closely with local artisans, using adobe, wood, and concrete to reflect regional materials and traditional forms.

This commitment to architectural minimalism mirrored his artistic concerns. Buildings were not façades but volumes of experience. The result is a town that feels more like a conceptual map than a tourist destination: silent facades, careful alignments, spaces that open suddenly into sunlit austerity.

The surrounding desert only intensified this effect. The Chihuahuan landscape became part of the aesthetic proposition—flat, spare, and immense. Visitors had to go to Marfa, a journey that mimicked pilgrimage: long drives, uncertain arrivals, altered perception. Time stretched. Cell signals dropped. Light became sculpture.

This sense of isolation was not incidental—it was the material. Artists and visitors alike found themselves stripped of context, left alone with form, shadow, and heat. In this vacuum, the slightest detail—the texture of aluminum, the length of a shadow, the color of sunset on concrete—took on heightened intensity.

But this minimalism wasn’t simply formal. It was philosophical. Marfa demanded a slowing down, a confrontation with presence. In an age of distraction, it offered the shock of clarity.

Three hallmarks defined the “Marfa effect” on art:

- Site as medium: works were inseparable from their location.

- Perceptual discipline: viewers were asked to look, and keep looking.

- Permanent installation: the work wasn’t a product to be moved or sold.

This ethos challenged the gallery-industrial complex and helped shift artistic attention toward long-term projects, land art, and non-commercial practice.

Art Pilgrimage and the Luxury of Distance

By the 1990s and early 2000s, Marfa had evolved from an avant-garde experiment into a cultural phenomenon. The Chinati Foundation attracted architects, collectors, curators, and eventually tourists. Boutique hotels, design stores, and curated experiences followed. What had once been Judd’s controlled retreat became a magnet for international art pilgrims—and, inevitably, for commerce.

Critics have long debated whether Marfa betrayed or fulfilled Judd’s vision. On one hand, his installations remain untouched, his principles preserved. On the other, the town around them has changed dramatically. Real estate prices soared. Aesthetic branding overtook local industry. The paradox deepened: a town built on minimalist rigor became synonymous with maximalist lifestyle marketing.

Yet something essential remains. Despite the boutiques and Instagram posts, despite the tensions between cultural outsiders and long-term residents, Marfa still offers a rare encounter with space, light, and art that refuses to explain itself. Visitors still walk among Judd’s boxes in silence. Flavin’s lights still pulse across barrack walls. The desert still blinks slowly in the heat.

What Judd initiated in Marfa was not a style but a method—a way of making and seeing that continues to influence artists across Texas and far beyond. From large-scale installation to architectural preservation, from permanent land-based work to radical slowness, the “Marfa model” offers a counterpoint to art as content: art as structure, as system, as space.

If earlier Texas art had shouted, Marfa whispered. And in that whisper, many heard something they’d never encountered before: stillness, form, and the unyielding honesty of the West Texas sun.

Contemporary Native Artists Reclaim the Narrative

For most of Texas’s visual history, Native presence has been either mythologized, marginalized, or erased altogether. Indigenous peoples—Comanche, Apache, Caddo, Karankawa, Tonkawa, and many others—appeared in paintings as adversaries, vanished ancestors, or symbolic figures rather than living creators. Their artistic traditions were classified as artifact, not art. But in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a significant reversal began: Native artists from and connected to Texas started not just making art, but reclaiming authorship, visibility, and historical agency in ways that challenged long-standing exclusions.

This was not a nostalgic return to lost traditions. It was a dynamic, often experimental reassertion of continuity, survival, and presence—rooted in place but looking forward.

Ghosts in the Canyonlands: Modern Rock Art Dialogues

One of the most striking aspects of contemporary Native art in Texas is how it re-engages with the land-based visual legacy of prehistoric rock art. The ancient pictographs of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands—once the domain of archaeologists and anthropologists—have become sources of inspiration and critique for artists today who recognize in them a lineage interrupted but not broken.

Artists like Letitia Huckaby, though not exclusively Native, have collaborated with tribal communities and used photography to evoke these ancient sites, blending archival memory with contemporary perspective. More directly, Indigenous artists with roots in the region have begun creating work that consciously parallels or references rock art’s symbolic systems—not to replicate them, but to dialogue with their obscured meanings.

This engagement isn’t merely aesthetic. It raises complex questions: Who owns this imagery? Who has the right to interpret it? What happens when ancient marks become tourist attractions or research data points?

In response, some Native artists have turned to site-specific installations, digital projections, or ephemeral interventions near ancestral spaces—using modern media to re-inscribe presence where cultural silence once loomed. Others adopt abstract motifs derived from ancient designs, reworking them into textiles, prints, or sculptures that refuse categorization as “craft” or “heritage.”

Three tendencies mark this new approach:

- Symbolic recursion: ancient motifs reappearing in new forms.

- Geographic fidelity: artworks tied closely to ancestral landscapes.

- Critical reclamation: challenging academic or institutional control over Native imagery.

Rather than treating prehistoric rock art as past, these artists make it a contested present—a visual inheritance demanding new eyes.

Beadwork, Performance, and Sovereignty

Contemporary Native art in Texas spans far beyond the image of the Southwest ceramicist or Plains ledger artist. It is as diverse as the tribes themselves, many of whom now live in diaspora or have no formal federal recognition. This fragmentation has led to an art that is self-aware, politically charged, and medium-fluid—encompassing beadwork, sculpture, photography, video, and performance.

One prominent thread is the recontextualization of traditional materials. Beadwork, once confined to regalia or ceremonial use, now appears in conceptual installations and high art settings. Artists bead maps, protest slogans, or corporate logos, transforming beauty into critique. The juxtaposition is deliberate: ancestral technique used to interrogate contemporary erasure.

Performance has become a particularly vital mode. Artists stage actions that reclaim land, ritual, or memory, sometimes in public spaces long associated with settler authority. A dancer moving across a courthouse lawn, a singer reciting tribal history at the edge of a highway, a video work projected onto a mission wall—these acts remake the geography of Texas as a place still inhabited by Native story and sovereignty.

Visual artists like Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw-Cherokee), while not Texas-based, have influenced regional artists with their fusion of pop culture, Native tradition, and queer identity. Meanwhile, Texas-affiliated artists draw on specific tribal affiliations—Lipan Apache, Caddo, Alabama-Coushatta—to root their practice in ongoing cultural realities, not generalized “Native” aesthetics.

These works often straddle institutions uneasily. Galleries and museums may be eager to exhibit Native artists but reluctant to confront the political content—land theft, broken treaties, environmental degradation—that animates much of the work. For the artists, this tension becomes material: how to be seen without being commodified.

What “Texas” Means After the Borders Shift

Perhaps the most profound contribution of contemporary Native artists is not aesthetic, but conceptual. By asserting their presence within Texas art, they challenge the very idea of what “Texas” is and was. After all, the borders that define the state were drawn through sovereign Native territories, often by force or fraud. To create as a Native person in Texas is to navigate a layered absence: of land, recognition, and narrative.

Artists respond to this condition not with despair but with revision. Their work asks us to rethink:

- Whose history has been told in the murals, monuments, and museums.

- Whose landscapes have been marked, both visually and politically.

- Whose aesthetic languages have been silenced, ignored, or appropriated.

By confronting these questions head-on, Native artists in Texas destabilize the dominant myths of frontier, heroism, and manifest destiny that have long shaped the state’s visual identity.

They also offer a vision of Texas that is less fixed and more alive—a place where histories collide but do not cancel, where modernity and memory coexist, and where art can be a form of intellectual and spiritual sovereignty.

In doing so, they don’t merely reclaim the narrative. They recompose the visual grammar of the state itself—from the pigment in a canyon wall to the bead on a museum pedestal, from a dance in a forgotten field to a name whispered back into the land.

The Global in the Local: Texas Art in the 21st Century

In the 21st century, Texas art has ceased to be a regional category—it is part of a global conversation, shaped by international currents, digital technologies, migration, and transnational networks. And yet, it retains a local force that remains stubbornly resistant to assimilation. Texas artists today move between biennials and back roads, between border towns and international fairs, without losing their particular sense of place. What defines contemporary Texas art now is not a fixed identity or style, but a tension between rootedness and reach—a duality that gives the state’s art scene its paradoxical vitality.

Houston’s Expanding Canvas

No Texas city better embodies this dual dynamic than Houston. Once viewed as culturally secondary to the coasts, Houston is now home to one of the country’s most dynamic, diverse, and globally engaged art scenes. The city’s non-zoning sprawl, ethnic complexity, and proximity to Latin America have made it a site of experimentation unlike any other.

Institutions like the Menil Collection, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) continue to shape national conversations. But what has distinguished Houston in recent decades is not just its big museums—it’s the network of artist-run spaces, alternative venues, and community-based initiatives that blur the line between high and low, elite and vernacular.

Artists such as Trenton Doyle Hancock, whose narrative-driven, cartoon-surrealist worlds blend myth, autobiography, and racial critique, have helped define Houston’s eccentric intellectual energy. Others, like Jamal Cyrus and Vincent Valdez, explore American memory, archive, and trauma through complex mixed-media installations, drawing on music, history, and iconography with global fluency.

Meanwhile, the city’s immigrant neighborhoods have become creative crucibles. In Gulfton, Alief, and the East End, murals, pop-up exhibitions, and grassroots arts organizations reflect an art scene that speaks not only in English and Spanish but also in Vietnamese, Urdu, and Arabic.

Three conditions give Houston its distinctive art character:

- No zoning laws, allowing ad hoc creative space to flourish in warehouses, bungalows, and storefronts.

- International traffic, including migrants, students, and expatriates fueling aesthetic exchange.

- Cross-sector collaboration, with artists working alongside scientists, engineers, and activists.

In this environment, Texas is not a periphery—it’s a node, a platform, and increasingly, a launch point for careers that move fluidly between the local and the global.

Biennials, Border Tensions, and New Media

Beyond Houston, other Texas cities have asserted themselves as cultural centers with their own idioms. The Dallas Art Fair, the East Austin Studio Tour, the Cinematexas International Film Festival, and Fotofest Biennial in Houston have drawn international audiences while showcasing local experimentation.

But some of the most significant developments in 21st-century Texas art have occurred at the border, where the cultural logic of the nation-state breaks down. In El Paso, Brownsville, and Laredo, artists have used performance, video, and installation to explore themes of surveillance, language, migration, and environmental trauma. The border is no longer just a theme—it is a medium, shaping the physical and conceptual space in which art is made.

Artists like Adriana Corral and Alejandro Macias work at the intersection of personal and geopolitical history, addressing state violence, memory, and the erasure of identities caught between flags. Others, such as Anida Yoeu Ali, though not native to Texas, have brought performance-based practice to Texan audiences with strong resonance—engaging questions of embodiment, surveillance, and ritual in the context of contested space.

Simultaneously, new media has transformed the reach and form of Texas art. Artists now engage with code, virtual environments, interactive installations, and AI-generated imagery. At institutions like the University of North Texas and Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, digital media programs have incubated hybrid practices that blur boundaries between disciplines. The internet has allowed rural artists to bypass geographic isolation, building audiences through online exhibitions, social platforms, and direct sales models.

And yet, despite all this technical mobility, many artists still return to core questions of place: what does it mean to live and work in Texas today? What is remembered, what is erased, and what can be made visible again?

Collectors, Controversy, and Cultural Memory

As contemporary art in Texas has matured, so too has its support infrastructure—though not without tension. A new generation of collectors, curators, and arts administrators has brought ambition and money to the scene, especially in Dallas and Houston. High-profile acquisitions, commissions, and exhibitions have raised the international visibility of Texas-based artists.

But visibility brings its own challenges. The desire for market viability sometimes clashes with the messier demands of history and politics. Controversial works—whether addressing gun violence, border policy, or historical revisionism—have provoked backlash from donors or institutions wary of politicization. In some cases, artists have self-funded their projects or worked outside official channels to preserve independence.

This friction has spurred a parallel art economy, where collectives, informal networks, and independent spaces provide both critique and support. Projects like The MAC in Dallas, Sala Diaz in San Antonio, and Artpace continue to offer platforms for experimental and underrepresented voices.

Contemporary Texas artists increasingly engage in archival recovery—mining family histories, church records, oral testimony, and forgotten ephemera to build new visual languages. This is not nostalgia. It’s reclamation: using the tools of contemporary art to repair absences, reinsert silenced figures, and rebuild cultural memory in the shadow of erasure.

At its best, Texas art in the 21st century is deeply aware of its own contradictions. It refuses easy narratives of frontier exceptionalism, yet it still draws power from geography. It participates in the global art market, but doesn’t surrender its dialects. It engages identity and history without retreating into slogans.

Most of all, it insists—sometimes quietly, sometimes defiantly—that Texas remains a place where art is not just shown, but shaped. Where the local is not a limit, but a lens sharpened by pressure, complexity, and weathered pride.