The first art ever made in what we now call Sydney wasn’t painted with oils or exhibited in white-walled galleries. It was carved into sandstone platforms, painted on rock shelters, and inscribed into the memory of land and people alike—an enduring visual record created by the Dharawal, Dharug, and Guringai peoples long before European arrival. Long overlooked by formal art history, these works remain some of the most physically rooted and spiritually charged images on the continent.

Sandstone Traditions: The Dharawal, Dharug, and Guringai Heritage

The Sydney Basin, with its weathered sandstone shelves and escarpments, proved an ideal canvas for generations of Aboriginal artists. Across areas that now bear suburban names—Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, Royal National Park—thousands of engravings and pigment works still survive. These weren’t random markings or decorative efforts; they served ceremonial, instructive, and mnemonic purposes, bound to systems of law, kinship, and territory.

Each group in the region practiced distinct artistic methods tied to their specific environments. Dharawal country, extending south toward the Illawarra, features more than 800 documented rock art sites, many of them deeply associated with spiritual life. The Dharug, who occupied much of what is now western Sydney, are known for their extensive carving grounds near waterways, where clear depictions of kangaroos, emus, and ancestral figures are still visible. To the north, in Guringai land, the engraving techniques often involved outline carvings of fish, whales, and eels—closely tied to coastal economies and seasonal migration cycles.

While Aboriginal rock art across Australia varies dramatically by region, the Sydney Basin works are stylistically distinct in their simplicity and scale. The engravings are often large—several meters across—and executed with clean outlines that emphasize form over detail. In pigment art, hand stencils dominate: hundreds of them left in ochre, sometimes layered across generations, sometimes paired with painted animals or weapons. These handprints are neither signatures nor decorative flourishes—they are traces of participation, testimony of presence, extensions of being.

Engravings and Meaning: Technique, Ritual, and Continuity

The rock engravings of Sydney were not carved with metal tools. Artists used pointed stones or shells to incise outlines into the sandstone, often abrading the grooves repeatedly over time to maintain visibility. These grooves—the result of significant labor—might represent a creator being, a clan totem, or an animal important to a seasonal rite. The act of engraving itself was part of ritual practice: a process that invoked connection to the ancestral world and renewed relationships with place.

Meaning, in this context, wasn’t always fixed or singular. Some engravings acted as markers—indicators of sacred sites or ceremonial grounds. Others were mnemonic, used during storytelling or initiation to teach cosmology, kinship laws, or hunting knowledge. Interpretation relied on context and custodianship. Without the oral traditions that accompanied them, these marks risk becoming illegible to outsiders.

That hasn’t stopped generations of Europeans from speculating. Early settlers often misread the works as “primitive graffiti” or “hunting maps,” unable or unwilling to understand their spiritual foundations. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, some were destroyed outright during roadworks, construction, or out of ignorance. Others were copied, catalogued, and interpreted through anthropological lenses that often reduced their complexity to fixed symbols—kangaroo equals food; shield equals warfare.

But these carvings were never fixed codes. They were alive in time. Some were periodically “recharged” through ceremony, others deliberately allowed to fade. The very idea of permanence was treated differently. Art, here, was not about preservation—it was about relationship, activity, and renewal.

One remarkable engraving at the Elvina Track site in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park shows a large figure with a distinctive headdress and outstretched arms. It’s often interpreted as a deity or ancestral being, possibly Baiame, the creator spirit. Measuring over three meters wide, it dominates the sandstone shelf, surrounded by smaller carvings of wallabies, fish, and shields. Nearby are grinding grooves, waterholes, and other signs of long-term ceremonial use. This is not isolated ornament—it is part of a ritual landscape.

Preservation and Neglect: Contested Custodianship of Ancient Sites

Sydney’s rock art sits uneasily in the modern city. Some of it lies in remote bushland, protected by national park boundaries and sometimes monitored by Aboriginal heritage officers. But much of it exists near roads, homes, or public infrastructure—forgotten or unmarked, vulnerable to weather, vandalism, and bureaucratic neglect.

In some cases, this neglect is not just accidental but systemic. Until the 1970s, Aboriginal heritage sites in New South Wales received minimal legal protection. In the postwar decades, thousands of carvings were destroyed during the expansion of suburbs, highways, and schools. Even now, despite heritage listings and growing public awareness, new construction projects often uncover previously undocumented sites—some of which are promptly reburied, fenced off, or left inaccessible to the Aboriginal communities connected to them.

There are exceptions. In recent years, several initiatives have sought to document and protect Sydney’s rock art more seriously. The Sydney Rock Art Project, led by archaeologist Paul Tacon and involving traditional custodians, has recorded hundreds of sites using 3D scanning and high-resolution imaging. Yet technical preservation is only one part of the story. For many Aboriginal people, access—not just physical but spiritual—is still constrained by the bureaucracies that govern national parks and museums.

There is also the question of visibility. Some sites, like the ones near Bondi or in the Royal National Park, have signage and walkways. Others are deliberately unpublicized to prevent vandalism. This tension—between education and protection—remains unresolved. Should rock art be made available to the public, or kept within the community that knows its meaning? Who decides, and under what authority?

It is not only an issue of heritage, but of power. For more than two centuries, Aboriginal knowledge systems were dismissed, overwritten, or absorbed into settler narratives. Even the naming of sites—referred to by catalog numbers or English place names—removes them from the cultural frameworks that created them.

And yet, these carvings endure. Across a city of five million people, beneath footpaths and behind schools, in patches of bushland between motorways, the oldest artworks in Sydney remain embedded in stone. They are not only remnants of a distant past. They are expressions of a continuous culture, one that never stopped making, remembering, or marking place.

First Contact, First Images: Early Colonial Depictions of Sydney

The first visual records of Sydney made by Europeans were not painted by professional artists but by sailors, surveyors, and naturalists—men who came to chart, claim, or catalogue, not to make art. Yet their drawings, watercolours, and prints became some of the earliest and most enduring images of the new colony. In them, we see the collision of unfamiliar landforms with European expectations, and the uneasy depiction of the Aboriginal people whose presence both fascinated and unsettled these newcomers.

Visual Arrival: Landscape Painting and Early European Perceptions

When Governor Arthur Phillip landed at Port Jackson in 1788, the British Crown had no formal art policy for the new penal colony. But from the beginning, images were made—not just for memory, but for communication. These pictures were sent back to London to show what the colony looked like, what it might become, and what had to be tamed or transformed. As such, even the earliest watercolours served both documentary and propagandistic purposes.

Thomas Watling, a convicted forger who arrived in Sydney in 1792, became one of the first known European artists to depict the colony with any consistency. His drawings capture the rawness of the landscape, often portraying the harbor’s rocky shores, native vegetation, and Aboriginal figures in naturalistic detail. Though his training in perspective and proportion was uneven, Watling’s work has a striking immediacy, blending curiosity with a kind of restrained wonder.

Other early images were produced by naval officers trained in draftsmanship. Captain John Hunter—later governor—made competent topographical drawings, while William Bradley illustrated events and landscapes with the pragmatic eye of a seaman. Their sketches, though lacking in painterly finesse, remain invaluable records of how the colony first appeared to European eyes.

These men did not arrive as artists in the romantic tradition. Their drawings were meant to inform, not inspire. Yet gradually, as the colony stabilised and travel between Sydney and England became more regular, a shift occurred. Artists began to arrive who saw the landscape not simply as terrain to be mapped, but as subject matter in itself. What began as record-keeping evolved, within decades, into something approaching landscape painting.

Recording the Aboriginal Inhabitants: Portraiture, Sketches, and Observation

Perhaps the most politically charged images from this early period are those of Aboriginal people. From the beginning, the presence of the Eora—whose land included Port Jackson—challenged the European claim to sovereignty. Artists, often unsure how to depict them, fell back on ethnographic conventions: portraying Aboriginal men with spears and shields, women with infants or in scenes of camp life.

Some of these images are surprisingly detailed and respectful. The portrait of Bennelong, made in England after he accompanied Governor Phillip to London, shows him in European dress with a poised, composed expression. Other sketches, however, veer into caricature or exoticism—reducing complex societies to generic “native” figures meant to arouse curiosity back home.

A number of artists depicted acts of violence, usually framing them as responses to Aboriginal aggression. But there are counterexamples, too—images that hint at dispossession or loss. In one watercolor attributed to Watling, two Aboriginal men stand on a promontory looking out to sea as a British ship sails into the harbor. Their posture is ambiguous: proud, perhaps, but also resigned. It is one of the few early images to suggest the arrival of the British was not merely a new beginning, but a rupture.

From a modern perspective, these depictions can be difficult to interpret. They reflect not only the biases of the artist but the purposes of their creation. Were these images intended to elicit sympathy, curiosity, or justification for colonisation? In many cases, the answer is all three.

What they do show—unequivocally—is that Aboriginal presence was not invisible to the first European artists. It was acknowledged, if not always understood. And it became one of the first motifs in what would eventually become a national visual tradition.

Art as Record: Naval Officers, Naturalists, and the Depiction of an Unknown Coast

In the early decades, the boundaries between science, art, and empire were porous. Naturalists like George Raper and Ferdinand Bauer were commissioned to record plant life, fauna, and terrain. Their drawings, often painstaking in detail, merged observation with aesthetics—botanical illustrations rendered not just for accuracy but for beauty. These works became part of a larger colonial project: making the land knowable, classifiable, and thus governable.

The early art of Sydney was, in this sense, deeply functional. It mapped a world that had not yet been fully surveyed. It catalogued plants and animals unknown to Europe. It offered visual proof of imperial expansion. But it also revealed the limitations of European perception. Mountains were drawn with English slopes; eucalyptus trees rendered with the softness of elms. The light—so hard and angular in reality—was diffused into the familiar haze of European skies. The artists didn’t just record—they interpreted, reshaped, and at times, imposed.

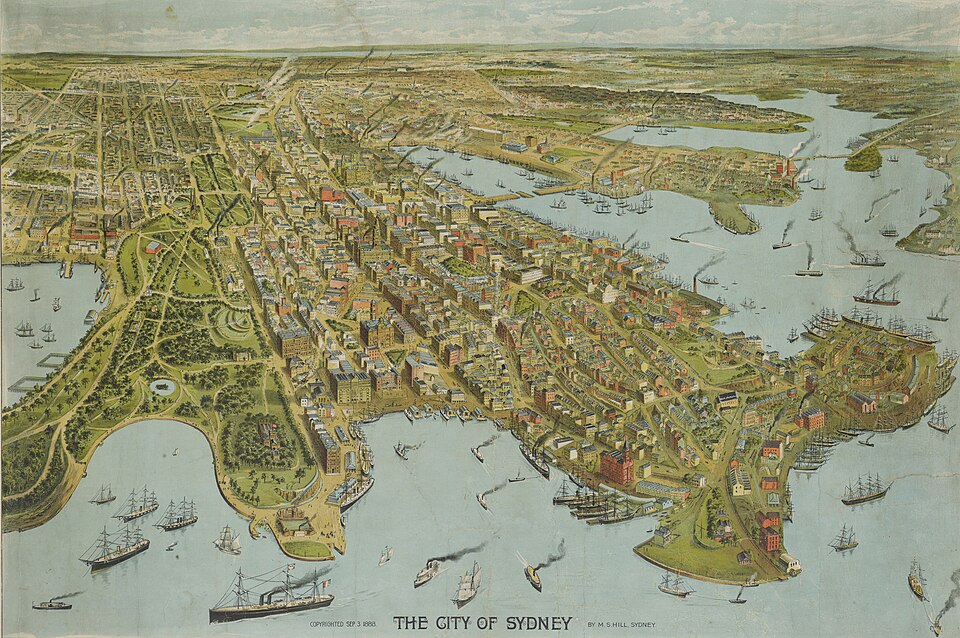

One particularly telling image is John Eyre’s “Panoramic View of Sydney” from the early 1800s. Made from an elevated vantage point, it shows the town’s early grid of houses, Government House, and the harbor beyond. But even here, the Aboriginal presence is reduced to decorative foreground figures—curious onlookers placed for compositional balance, not narrative truth. The painting offers a neatly ordered world where conquest is already complete, and settlement is a matter of time.

But the reality on the ground was far more contested. As disease, displacement, and skirmishes took their toll on local Aboriginal populations, the pictures became less frequent, more stylised. By the 1820s, Aboriginal people had largely disappeared from colonial imagery—not because they were gone, but because they no longer fit the visual story the settlers wanted to tell.

These early works, then, serve a dual function. They are records of an unfamiliar world, and of a worldview being imposed upon it. They show how Europeans tried to make sense of what they saw—and how, in the process, they changed what they were capable of seeing.

A View from the Shoreline: Convict Artists and the Visual Language of Work

The story of Australian colonial art often begins with the gaze of European officers and explorers, but some of the earliest and most compelling images of Sydney were made by convicts. Trained in skills like draftsmanship, engraving, or painting—often acquired before sentencing—these men worked under duress, for authorities who valued their talents as tools of administration. Yet despite the conditions of their captivity, convict artists contributed a visual grammar that shaped how the colony saw itself: utilitarian, documentary, and curiously detached.

The Eye of the Punished: Forgeries, Topographies, and Discipline

Among the earliest and most prolific of these figures was Thomas Watling, a Scottish forger transported to New South Wales in 1792. While Watling is remembered today for his vivid watercolours of landscapes, plants, and Aboriginal life, his criminal conviction stemmed from a different kind of image-making—counterfeit banknotes. Like several other artist-convicts, he was conscripted into the colonial apparatus not as punishment but as productive labor, where his artistic skill found official use.

Much of Watling’s output consisted of straightforward representations of daily life in the penal settlement: barracks, supply ships, military drills, and the raw grid of the nascent township. These were not private works or expressions of personal vision. They were made to be sent back to Britain—either by colonial administrators or entrepreneurial publishers—as evidence of development, order, and progress. In this sense, convict art was part of a larger visual project: legitimizing the colony through images of its function.

Yet the tension between artistic freedom and institutional control is often visible in the work itself. In a watercolor showing Sydney Cove from the west side, Watling carefully records the outline of tents and storehouses, but the figures of Aboriginal men on the shore are gestural, even ghostlike—present but peripheral. Whether this omission was stylistic or politically cautious is impossible to know, but it reflects a broader pattern: convict art rarely challenges power, even as it records its workings.

Some of the most precise early views of Sydney were made not in paint but in ink and copperplate. George Evans, another convict with surveying experience, created detailed maps and engravings that combined aesthetic clarity with bureaucratic intent. These images, though unsigned and often unattributed, helped establish the idea of Sydney not as a prison camp but as a growing township—a place with streets, fences, and taxable assets. In the hands of convict artists, the landscape was transformed into documentation, measured and managed.

Convict labor also shaped artistic infrastructure in more literal ways. Prisoners carved decorative stone for public buildings, painted interior murals, and even fabricated ornamental elements for churches and official residences. Art in this context was not a luxury—it was a function of order. To be a skilled artisan was to become part of the colonial machine.

Joseph Lycett and the Aesthetics of Surveillance

If Watling documented Sydney with a draftsperson’s restraint, Joseph Lycett—another convicted forger—offered a more stylized, even idealized, version of colonial life. After being transported in 1814, Lycett found favor with government officials and eventually secured a role producing landscapes and portraits for the colonial elite.

Lycett’s most famous publication, Views in Australia, released in London between 1824 and 1825, presented a series of picturesque images depicting New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. The Sydney scenes are serene: river bends, pastoral settlements, tidy roads, and prosperous-looking farms. Indigenous figures appear only as graceful silhouettes in the foreground—present, but unthreatening.

These images were commercial and strategic. They reassured British audiences that the colony was safe, productive, and scenic—a place for settlers, not just prisoners. But beneath their pastoral calm lies a deeper surveillance function. Every fence, path, and boundary in Lycett’s work is clearly demarcated. Land, in his images, is always under control: surveyed, owned, and improved.

This clarity was not accidental. Lycett worked closely with colonial surveyors, and many of his compositions mirror cadastral maps in their geometry. In this sense, his art anticipates the role of visual culture in enforcing authority. To draw the land was, in a very real way, to claim it. To paint it orderly was to deny its history of conflict.

Yet Lycett’s work occasionally slips the leash of pure documentation. His use of atmospheric perspective, soft light, and sweeping vistas owes more to European landscape painting than to bureaucratic record-keeping. It’s a curious blend: a penal artist producing promotional imagery in a romantic style, his forgeries now replaced by views that forgave the land its strangeness.

Lycett died in England under uncertain circumstances not long after his book was published. His images, however, continued to circulate. They shaped British perceptions of Australia for decades—more so than any dispatch or government report. In their precision and serenity, they helped turn a penal experiment into a destination.

From Forced Labor to Marketable Art: Turning Penal Imagery into Trade Goods

The evolution of convict art into a marketable genre did not occur in a vacuum. As Sydney grew, so too did demand for images—by visiting officers, emigrating families, and local notables. Artworks once made for official use began to circulate privately. Watercolours changed hands. Prints were copied and sold. In time, convict artists became part of a visual economy that extended beyond the penal system.

Some former convicts parlayed their skills into post-sentence careers. Francis Greenway, perhaps the most famous example, was transported for forgery but became the colony’s official architect under Governor Macquarie. Though best known for buildings like St James’ Church and the Hyde Park Barracks, Greenway also left behind architectural drawings of notable elegance—images that bridged utility and beauty.

Others disappeared into anonymity. The vast majority of convict artists remain nameless, their work unsigned or misattributed. What survives are the products of a system that used artistic labor not for expression, but for control: to plan cities, document change, and project legitimacy to an imperial audience.

But even within that system, a strange kind of artistry flourished. The discipline of accuracy, the demands of order, the constraints of punishment—these all shaped the visual culture of early Sydney in ways that remain visible. The convict gaze was not romantic or political. It was trained, often under duress, to see what needed to be shown—and to show it clearly.

The irony is not lost: that some of the colony’s most enduring images were made by men imprisoned for making false ones. In that reversal lies a quiet historical echo, a reminder that Sydney’s artistic foundations were built not on aesthetic freedom, but on the exacting demands of a penal state.

Empty Landscapes and Romantic Visions: Colonial Landscape Painting in Sydney

In the mid-19th century, as the penal colony of New South Wales began to recast itself as a civilised and prosperous outpost of empire, landscape painting emerged as the dominant artistic form in Sydney. No longer confined to maps or documentary sketches, the local terrain became the subject of aesthetic ambition—imbued with light, distance, and moral narrative. But this romantic transformation came at a cost: the land was not only idealised but emptied, its prior inhabitants either diminished or erased.

John Glover and the European Arcadia in Australia

Though John Glover was based primarily in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), his influence on Sydney’s artistic circles was significant. Trained in the English picturesque tradition, Glover emigrated to Australia in 1831 at the age of 64, bringing with him a fully formed European aesthetic. His paintings of the Australian bush—clear, spacious, and sunlit—stood in contrast to the darker, denser views made by earlier European artists. Glover gave Australia a pastoral face, one that settlers and patrons welcomed eagerly.

His vision was not documentary but idealised. In A View of the Artist’s House and Garden, Mills Plains, for instance, the eucalypts are rendered with botanical accuracy, but the overall composition—with gently undulating land, symmetrical tree placement, and harmonious skies—mirrors 18th-century English estate painting. The land is domesticated, even when its elements are unfamiliar. This was Arcadia with gum trees.

What makes Glover’s work especially revealing is its shifting treatment of Aboriginal figures. In earlier paintings made shortly after his arrival, he often includes Aboriginal people engaged in ceremony, fishing, or simply existing within the landscape. But as the years progressed, these figures vanish. The land becomes less inhabited and more available—ready, in visual terms, for settlement. The absence is not neutral. It is narrative.

Sydney-based artists absorbed this sensibility quickly. Landscape painting became a means of visual reassurance: a way to imagine that the colony was not built on conflict but on open land waiting for cultivation. The wildness of the bush could be shown, but only in controlled compositions. The land might be ancient, but in art it was always ready to be new.

The Blue Mountains Sublime: Illusion, Distortion, and Erasure

Nowhere was this dynamic more apparent than in depictions of the Blue Mountains, the rugged escarpment west of Sydney that loomed large in colonial mythology. Crossing the range in 1813 had been a major achievement—opening up access to inland plains and securing agricultural expansion. By mid-century, the Blue Mountains became not just a physical barrier, but a symbol of the colony’s triumph over nature.

Painters like Conrad Martens, Sydney’s most prominent landscape artist of the time, took full advantage of the mountains’ drama. A trained topographer who had sailed with Darwin on the Beagle, Martens brought a cultivated European eye to the Australian landscape. His watercolours and oils show sweeping valleys, jagged cliffs, and dramatic skies—compositions that owe as much to the European sublime as to geographic fact.

But these images often relied on visual strategies that altered reality. Steep slopes were softened, foliage tidied, and scale manipulated to suit the grandeur of composition. In Martens’ View of the Blue Mountains, the sense of untouched majesty is palpable, but entirely aesthetic. The image offers no indication that the area was traversed, lived in, and known long before Blaxland, Lawson, and Wentworth made their 1813 expedition.

Indeed, the sublime in colonial art served a double purpose. It conveyed awe and conquest simultaneously. The land is vast, but it is already contained by the viewer’s eye. It overwhelms, but it does not threaten. And in almost every case, it is empty—not just of people, but of history.

That emptiness was, in fact, an invention. The Gundungurra and Darug peoples had walked and managed these ranges for millennia. They left behind pathways, stories, and ceremonial sites. But in the eyes of colonial artists, the mountains became a natural theatre—raw and waiting to be seen. The act of painting them became part of a cultural campaign: to reframe inhabited territory as frontier.

Omitting Aboriginal Presence from the Painted Landscape

This visual erasure was neither accidental nor subtle. In countless paintings from the 1830s to the 1870s, Aboriginal people are absent, marginalised, or rendered symbolically. When they do appear, they are often distant—reduced to silhouettes, decorative staffage placed for contrast against the scale of nature. Their presence enhances the scene’s exoticism but says nothing about its reality.

The reasons were not purely aesthetic. As settler society deepened its roots in Sydney and its surrounds, there was a growing psychological need to justify possession of the land. The doctrine of terra nullius—though not yet formalised in law—was already being enacted in pictures. Empty landscapes suggested moral clarity: that the land was unclaimed, unworked, unowned until the colonists arrived.

Painters like Eugene von Guérard, though based in Melbourne, had exhibitions in Sydney and influenced its cultural circles. His panoramic landscapes are technically brilliant and deeply admired—but they often depict Australia as pristine wilderness, untouched by human presence. This was not just a convention; it was a worldview.

Yet there were exceptions. Some works by less prominent artists—often unsigned or amateur—showed Aboriginal families camped near rivers, walking along roads, or trading with settlers. These images, though rare, suggest that visual honesty was not impossible. But they did not dominate exhibitions or travel to London. They did not enter the canon.

Even Martens, the most established Sydney painter of his time, avoided depicting scenes of conflict or coexistence. His canvases show us the progress of roads, the stability of buildings, the grace of the harbour—but not the dislocation unfolding just beyond the frame.

And this absence has consequences. For generations, these landscapes defined the visual memory of early Sydney. They shaped how Australians imagined their origins—not through records of hardship or resistance, but through vistas of promise and peace. In these paintings, the land does not resist. It waits.

But the rocks still hold their markings. The rivers still follow ancient paths. And even as artists of the colony painted over presence, the land itself kept its stories. What was erased in pigment remained in stone and soil, waiting to be seen again.

Brush and Nation: Sydney and the Rise of Australian Impressionism

By the late 19th century, Sydney was no longer a penal settlement but a booming colonial capital, flush with mercantile ambition, urban expansion, and a restless desire for cultural definition. In the art world, this period saw a decisive shift: from European-trained formalism to a looser, more responsive style that sought to capture the distinct light, climate, and mood of the Australian landscape. Impressionism, as adapted by Australian painters, was not just an aesthetic import—it became a way to declare independence from both academic tradition and colonial self-consciousness. At its heart, it was a movement about seeing the country as its own subject, rather than as a substitute for somewhere else.

Sydney v. Melbourne: Rival Schools, Rival Visions

The rise of Australian Impressionism is often associated with Melbourne, particularly the artists’ camp at Heidelberg and figures like Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Charles Conder. But Sydney had its own circle of plein air painters, equally ambitious and arguably more experimental. The rivalry between the cities was not merely artistic; it mirrored deeper cultural and economic tensions. Melbourne prided itself on European sophistication, while Sydney cultivated a rougher, more pragmatic self-image—closer to the harbour, the trade routes, the bush.

In the 1880s and 1890s, artists gathered in informal collectives around the outskirts of Sydney, particularly in areas like Cremorne, Mosman, and the Hawkesbury River. These bush-fringed suburbs offered access to both natural light and painterly isolation. The Sydney camps were smaller and less institutionalised than their Victorian counterparts, but they shared a commitment to painting outdoors, rapidly, and with attention to the shifting effects of light and shadow.

One of the most notable figures in this scene was Julian Ashton, an English-born artist who had arrived in Sydney in 1878. Though classically trained, Ashton embraced the ethos of direct observation and championed the development of a recognisably Australian style. His school, founded in 1890, trained a generation of painters who would later define Sydney’s contribution to Impressionism and modernism alike.

Unlike the monumental ambitions of some of their Melbourne peers, Sydney’s painters often turned toward the intimate: boats at anchor, dusty rural roads, sunlit verandahs, and harbourside inlets. The palette was brighter, the brushwork looser, the compositions less heroic but more immediate. If Melbourne painted the bush as myth, Sydney painted it as habitat.

This is not to say the Sydney painters lacked technique or ambition. Tom Roberts, though more closely associated with Melbourne, spent significant time in Sydney and maintained close ties with Ashton and his circle. His work A Break Away!—painted after a New South Wales sketching trip—blends dynamism with dust, drama with realism. In it, the chaos of a sheep stampede becomes a study in movement and light.

But while the cities shared personnel, their artistic moods diverged. Melbourne’s painters pursued the bush as narrative; Sydney’s tended to capture the coast, the riverbanks, the quiet immediacies of daily life. Both sought to break from the imported European gaze, but they looked in different directions.

Tom Roberts, Charles Conder, and the “National Light”

The quest for a “national light”—a uniquely Australian way of seeing—became a kind of artistic obsession in the 1880s. Roberts, Conder, and Streeton, whether painting at Box Hill or Coogee, claimed that the high-key palette of French Impressionism was ill-suited to the dry brilliance of Australian skies. They adapted instead: clearing their colours, sharpening their contrasts, and choosing compositions that maximised sunlight and atmospheric clarity.

In Sydney, this meant painting around the harbour’s edge, where the interaction of water, rock, and sky created a chromatic complexity unfamiliar to European eyes. Charles Conder’s works from this period, such as Departure of the Orient – Circular Quay, combine the elegance of Art Nouveau line with the observational freshness of plein air technique. He captures not only the visual impression of a steamer’s departure, but also the social mood—the bustle, the anticipation, the colony’s growing entanglement with the wider world.

Sydney’s sunlight became, for these painters, a revelation. It flattened shadows, clarified contours, and demanded a reconsideration of how colour and form could work on canvas. Many of their works look sparse to European eyes—not because of laziness, but because of the radical difference in light. Where the French painted haze, the Australians painted glare.

This shift was more than technical. It suggested a different attitude toward the land itself. No longer a place of distant awe or colonial anxiety, it became a place to inhabit, to depict with intimacy rather than imposition. In this sense, Impressionism in Australia was not just a style—it was a statement of belonging.

Yet these works also carried unexamined assumptions. The landscapes they painted were often pastoral or uninhabited; the working class appeared in moments of bucolic leisure or picturesque toil. Aboriginal presence, when depicted at all, was token or abstracted. As with earlier landscape traditions, Impressionist painting helped normalise the idea of settled space—framed and filtered through a selective gaze.

Still, the vibrancy and technical confidence of this period remain striking. The 1890s may have been a time of economic depression and political uncertainty, but in the art world, they marked a flowering of confidence. The bush was no longer alien. It was, for better or worse, ours.

Women Painters on the Margins: Jane Sutherland and Her Peers

The story of Australian Impressionism has long been told as a male affair—Roberts, Streeton, McCubbin, Conder. But women were present, painting alongside the men, exhibiting in the same galleries, and contributing significantly to the movement’s visual language. In Sydney, women artists often worked under more difficult conditions: limited access to training, exclusion from artist camps, and the burden of domestic expectation. Yet their work demonstrates a keen eye, strong technique, and subtle innovation.

Jane Sutherland, though based in Melbourne, is an instructive case. Her work pushed beyond decorative floral studies into ambitious plein air compositions, sometimes including female subjects in bush settings—a visual counterpoint to the male-dominated shearers and stockmen of her peers. Her influence was felt in Sydney circles, particularly among women trained at the Julian Ashton Art School, which—unusually for its time—welcomed female students from its earliest days.

Artists like Isabel McGowan, Dora Meeson, and Sydney Ure Smith’s later collaborators helped create a space for women in the Sydney art scene, even if they did not always receive the same critical attention. Their works often focused on gardens, interiors, or harbourside scenes—not because of limited imagination, but because these were the spaces available to them. Within those limits, they produced work of clarity and lyrical strength.

These artists were not consciously challenging gender roles or seeking visibility in modern feminist terms. But their persistence, skill, and quiet ambition laid the groundwork for future generations. Their marginalisation was not due to lack of ability, but to the structures of the time.

As the 19th century closed and Federation approached, Australian art stood at a turning point. Impressionism had given painters a new vocabulary—sunlight, immediacy, belonging—but it had also inherited old habits of omission. What would follow, especially in Sydney, was a reckoning with form, identity, and the politics of seeing.

Institutional Foundations: The Emergence of Galleries and Art Schools

Art movements do not thrive in isolation. Behind every period of innovation lies a structure of education, patronage, exhibition, and debate. In Sydney, these foundations were laid during the final decades of the 19th century and shaped decisively in the early 20th. As galleries opened and art schools formalised their programs, the city developed not just a community of artists but a civic culture that treated visual art as something to be taught, preserved, and contested. The institutions created in this period—particularly the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the Julian Ashton Art School—remain central to Sydney’s artistic identity today.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales: Origins and Influence

The Art Gallery of New South Wales began modestly. Established as the New South Wales Academy of Art in 1871, it held its first exhibitions in borrowed spaces, with a clear mission: to elevate taste, educate the public, and encourage excellence in Australian painting. By 1885, with the construction of a dedicated building overlooking Sydney’s Domain, the institution had gained stature, both symbolic and practical. It became the central venue for public art in the colony and a critical gatekeeper for what was to be considered part of the nation’s cultural inheritance.

From the beginning, the gallery saw itself as both repository and arbiter. It acquired work through competition, committee, and occasionally controversy. The annual Wynne Prize for landscape painting (established in 1897) quickly became one of Australia’s most prestigious awards. But its selections often revealed tensions between tradition and experimentation, nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

The gallery’s early collections were dominated by British imports—Victorian genre scenes, portraits, and grand narratives—reflecting the colony’s continued cultural alignment with London. But Australian works gradually gained ground. Landscapes by Streeton, Roberts, and McCubbin entered the collection, though often belatedly. More radical or modernist works, particularly those associated with the emerging Sydney modernist scene of the 1930s and 1940s, were sometimes excluded outright.

This conservatism had long-term consequences. While the gallery became a site of civic pride, it also became a battleground—especially in the 20th century—for debates over artistic relevance, nationalism, and public taste. Even so, its role as a public institution was crucial. It offered artists visibility, audiences access, and the broader public a sense of their place within a larger visual story.

The building itself—neoclassical, elevated above the park—asserted a quiet authority. It told viewers that art mattered, that it belonged in stone halls and on civic calendars. That assumption, once radical in the colonies, had become part of Sydney’s cultural architecture.

Julian Ashton and the Shaping of a Distinct Australian Style

If the Art Gallery of New South Wales represented institutional consolidation, Julian Ashton represented individual vision. Born in England in 1851 and trained in the rigorous drawing schools of Paris, Ashton immigrated to Australia in 1878 and soon became a fixture of Sydney’s art world. In 1890, he founded what became the Julian Ashton Art School, now the oldest continuous art school in the country.

Ashton’s influence extended far beyond his own canvases. He believed in disciplined observation, strong draftsmanship, and the importance of working from life. His students were taught to draw before they painted, to understand anatomy before abstraction, to find their subject in the world around them—not in classical myth or foreign models.

This pedagogical philosophy produced a generation of technically skilled and locally grounded painters. Among Ashton’s students were Elioth Gruner, George Lambert, and Thea Proctor—artists who would each, in different ways, help define Australian modernism. Even those who later rebelled against Ashton’s principles retained the solidity of his training. His school became a crucible: a place where young artists encountered both structure and stimulus.

Importantly, Ashton welcomed women into the school from its earliest days. At a time when formal instruction was often closed to female students or limited to decorative arts, this decision helped shape a more inclusive Sydney art scene. Figures like Sydney Long, Dorrit Black, and Grace Cossington Smith either passed through the school or felt its influence indirectly.

Ashton was not a radical. He remained sceptical of avant-garde movements and wary of too much abstraction. But his commitment to local subjects, plein air practice, and rigorous craft helped give Australian painting a core from which later innovations could depart. The school still operates today, maintaining a commitment to traditional drawing and painting that links contemporary Sydney artists to a lineage stretching back over 130 years.

Sydney Technical College and the Role of Formal Training

Alongside the private influence of Ashton’s school, Sydney Technical College played a crucial public role in developing artistic skill. Established in 1878 and expanded in the early 20th century, the college offered training in applied arts, design, and fine art, aiming to meet both industrial and cultural needs.

The distinction between fine and applied arts—so entrenched in European academies—was less rigid here. Students learned etching, printmaking, architectural drawing, and photography alongside painting and sculpture. The college trained not only painters, but commercial illustrators, craftsmen, and future teachers. In this sense, it broadened the idea of what an artist could be in Australia.

One of its most notable students was Roland Wakelin, whose later experiments in colour and abstraction helped usher in a modernist vocabulary. Another, Dattilo Rubbo, an Italian-born painter who joined the faculty in 1897, became a dynamic and sometimes controversial figure in the college’s art department. Rubbo encouraged experimentation and attracted a following of younger painters, including Roy de Maistre, who would go on to pioneer abstract art in Australia.

The college also offered access. Whereas private instruction often required means or connections, Sydney Technical College allowed a broader demographic to pursue artistic training. This helped democratise the city’s visual culture—bringing in voices from outside the traditional art establishment and creating pathways for talent to emerge from unexpected quarters.

By the early 20th century, Sydney possessed a functioning, if imperfect, artistic infrastructure: a public gallery that curated taste, schools that nurtured technique, and a growing audience ready to engage with visual culture not just as colonial import, but as something rooted in their own place and time. The groundwork had been laid. What remained was the question of what to do with it.

Modernism Arrives: Sydney’s 20th-Century Awakening

The first decades of the 20th century brought seismic changes to Sydney’s art world—not through immediate revolution, but through gradual unraveling. The conventions of academic realism, the pastoral mythologies of Federation-era painting, and the civically minded landscape traditions of the 19th century all began to fracture under the weight of a modernising city, new artistic influences, and broader global currents. Modernism did not arrive in Sydney as a single ideology or manifesto, but as a series of provocations: aesthetic, cultural, and personal. Its rise was uneven, contested, and deeply formative.

Margaret Preston and the Modern Use of Aboriginal Motifs

Among the earliest and most influential voices in Sydney’s modernist turn was Margaret Preston, whose work embodied both the aspirations and contradictions of the period. Trained in Munich and Paris, Preston returned to Sydney in the 1920s determined to create an art that was distinctly Australian—not merely by subject, but by form and technique. She sought an antidote to imported academicism, and she found part of it, controversially, in Aboriginal art.

Preston was drawn to the formal qualities of Aboriginal design—its use of pattern, asymmetry, and flat perspective. She incorporated these elements into her woodcuts and paintings, particularly in her still lifes and landscapes, which often combined native flora with bold graphic outlines. In doing so, she produced some of the first non-Indigenous Australian artworks that consciously sought inspiration from Aboriginal visual traditions.

Her 1925 essay “The Indigenous Art of Australia” argued that a truly national art must absorb and build upon Aboriginal aesthetics. The statement was sincere, but it also reflected the cultural blind spots of its time. Preston approached Aboriginal art as raw material for modernist synthesis, not as a living system of meaning. She admired its visual strength but treated it largely as a formal vocabulary to be reinterpreted by the settler artist.

This approach has since drawn criticism, and rightly so. But Preston’s work remains a turning point: she brought Aboriginal art into conversation with modernism, albeit on unequal terms. Her engagement was flawed, but it was also foundational. She opened a space—however clumsily—for future artists to take the question of cultural inheritance more seriously and more respectfully.

More importantly, Preston helped redefine the parameters of Australian art. Her still lifes of waratahs and banksias, set against stylised backgrounds, were unapologetically local in subject and resolutely modern in form. She made it possible to be both Australian and avant-garde.

Grace Cossington Smith: Domestic Interiors, Radiant Light

While Preston made her impact through assertive public statements and sharply outlined woodblocks, Grace Cossington Smith worked with quiet persistence, developing a luminous, personal modernism that found beauty in the everyday. Her 1915 painting The Sock Knitter is often cited as Australia’s first modernist painting—its flattened planes and rhythmic brushwork signalling a break with naturalism—but it was her later interiors and landscapes that most fully realised her vision.

Cossington Smith never studied abroad, and her work remained firmly rooted in the life around her: suburban homes, garden paths, sitting rooms filled with afternoon light. Yet she brought to these scenes a remarkable sensitivity to colour and form. Her brushwork—short, deliberate, vibrating with tonal shifts—transformed ordinary objects into radiant harmonies.

In paintings like Interior with Wardrobe Mirror (1955), Cossington Smith used spatial distortion and radiant colour to render the domestic world as a place of transcendence. The mirror does not reflect so much as refract; the room itself seems to shimmer. She brought to Australian modernism a sense of stillness and interiority that contrasted with the bolder, more confrontational styles emerging elsewhere.

Her landscapes, too, are distinctively Sydney. The hills around Turramurra, the filtered sunlight of North Shore gardens, the arches of the Harbour Bridge—these became recurring motifs. But unlike earlier landscape painters, Cossington Smith did not present these scenes as national icons or picturesque views. She painted them as experienced spaces, suffused with colour, pattern, and atmosphere.

Despite her achievements, Cossington Smith remained on the margins of critical acclaim during much of her life. Her refusal to travel, to align herself with movements or manifestos, and her subject matter—all contributed to a certain critical neglect. But in retrospect, her work stands among the most original and enduring of Australian modernism. She painted not to argue, but to see.

Sydney’s Role in Formal Innovation and International Exchange

While Melbourne remained the centre of certain artistic institutions, Sydney emerged in the interwar years as a dynamic node for formal experimentation. This was partly due to geography: Sydney’s proximity to Pacific trade routes and its role as a port city made it more porous to global influence. European migrants, international exhibitions, and local artists returning from overseas study brought with them ideas that unsettled old hierarchies.

In 1913, the Society of Artists held its first annual exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales—a show that included works by Roland Wakelin, Roy de Maistre, and Grace Crowley, all of whom would become central to Sydney’s modernist vanguard. These artists were interested in colour theory, abstraction, and the expressive potential of form. They moved between figurative and non-objective modes, often ahead of public taste and institutional support.

One of the most notable developments was de Maistre’s exploration of “colour-music,” a synesthetic theory that sought to align musical tones with visual colours. Working with de Maistre, Wakelin produced paintings that experimented with formal harmonies, applying theories derived from both modernist painting and musical composition. Though these works were not immediately embraced, they signalled a new seriousness—a belief that Sydney could produce art that was not just derivative but intellectually rigorous.

Meanwhile, Dorrit Black, another key figure in Sydney’s modernist awakening, brought back from Europe the principles of Cubism and applied them to Australian scenes. Her work, along with that of Grace Crowley and Frank Hinder, helped foster an abstraction movement in Sydney that gained ground in the 1930s and 1940s. These artists were not working in isolation. They were part of a global conversation, albeit one carried out at a geographical distance.

Yet Sydney’s art world remained divided. The official institutions—the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Royal Art Society—often resisted abstraction and clung to tonal realism. The artists pushing modernist ideas found themselves exhibiting in alternative venues, supported by private patrons or small journals. The result was a dual culture: official conservatism on one hand, and experimental modernism on the other.

This tension would persist for decades. But it was precisely this friction—between institution and innovation, between European models and local experience—that gave Sydney modernism its vitality. It was not a unified movement, but a field of competing ideas, aesthetic gambits, and small, cumulative revolutions.

By the outbreak of World War II, the city’s artistic scene had matured into a dense, dynamic web. Its artists had embraced modernism not as a doctrine, but as a set of questions—about form, identity, and the possibility of making something new from a place still reckoning with its past.

War, Migration, and the Postwar Boom in Public Art

The Second World War reshaped Sydney’s cultural life in profound and lasting ways. When the war ended in 1945, the city entered a new phase: economically buoyant, demographically altered, and institutionally recalibrated. Art was no longer the domain of a small circle of professionals or connoisseurs. It was brought into civic spaces, woven into infrastructure, and reshaped by the arrival of artists from across Europe. Public art became a defining feature of Sydney’s postwar identity—ambitious in scale, modern in spirit, and increasingly diverse in voice.

Anzac Memorials and the Sculpting of Civic Remembrance

Sydney’s first major public artworks after the war were monuments—solemn, figurative, and rooted in the language of national grief. These memorials were not designed to provoke or innovate. Their purpose was ceremonial: to name the dead, to solemnise loss, and to offer a space for collective reflection.

The Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park, completed in 1934 but gaining renewed significance after 1945, became the central symbolic site of remembrance. Designed by Bruce Dellit with sculptures by Rayner Hoff, the memorial was modern in design but classical in spirit. Hoff’s interior reliefs—muscular, mournful, and allegorical—combined Art Deco stylisation with traditional motifs of sacrifice and valor.

Hoff had caused controversy in the 1930s with designs that depicted grieving mothers and wounded soldiers with raw emotional honesty. Some of his proposed works, including a depiction of a dead soldier crucified on a war goddess’s sword, were rejected as too provocative. But even in their approved forms, his sculptures introduced a more expressive, human dimension to public memorials—one that would influence later commemorative art in the city.

Postwar Sydney saw a continuation of this figurative tradition, but with subtle shifts. Monuments to the Second World War, the Korean conflict, and later Vietnam often included names of the fallen engraved into stone or bronze—emphasising individual sacrifice over abstract idealism. Public sculpture was now expected to mediate between personal loss and civic pride, not to glorify war but to dignify those caught in it.

Yet not all public art in this period was commemorative. Increasingly, sculpture and mural work were being integrated into civic buildings, parks, and transport infrastructure—not as monuments, but as part of everyday experience.

Postwar Abstraction and New Influences from European Migrants

One of the most significant shifts in Sydney’s postwar art came from beyond its borders. Australia’s immigration program, expanded dramatically after 1945, brought in hundreds of thousands of new arrivals—many from war-ravaged parts of Europe. Among them were trained artists, designers, and architects who introduced new styles, techniques, and philosophies to a city still dominated by conservative tastes.

László Peri, a Hungarian sculptor who settled in Sydney in the early 1950s, brought with him a background in Constructivism. His geometric public sculptures, made from welded steel and cast concrete, marked a break from the figurative traditions of prewar art. These works, often installed in parks or outside public buildings, offered a new vocabulary: angular, industrial, abstract. They were not always loved, but they forced viewers to reckon with unfamiliar forms.

At the same time, local artists were embracing international trends. Robert Klippel, trained in both Sydney and New York, began producing complex assemblages that blended Surrealism with post-industrial materiality. His large-scale metal sculptures—dense with rivets, plates, and architectural fragments—were acquired for public display and helped introduce non-representational art to a broader audience.

Painting, too, underwent radical change. John Passmore, who had studied in London and absorbed the lessons of Cézanne and synthetic Cubism, returned to Sydney and began teaching at East Sydney Technical College. His students—among them Colin Lanceley and Ann Thomson—took his structural approach and pushed it further, embracing bold colours, experimental media, and open composition.

This was a period of aesthetic pluralism, not consensus. Some public works remained comfortably figurative—mosaics of swimmers at public pools, bas-reliefs on courthouse façades. Others ventured into abstraction, provoking debate over the role of public funding and the boundaries of “taste.” But all were shaped, in some way, by the postwar influx of artists and the shifting expectations of a modern city.

Sydney was becoming not just a site of production, but a site of encounter. Its art reflected the tensions and possibilities of migration: the negotiation between continuity and disruption, between inherited traditions and new materials. The city’s visual identity was no longer defined by gum trees and pastoral calm. It was becoming urban, textured, and—cautiously—global.

Sculpture by the Sea and the Remapping of Coastal Culture

In the decades that followed, Sydney’s relationship to public art expanded beyond monuments and municipal commissions. Perhaps the most visible example of this shift came in the late 20th century with the launch of Sculpture by the Sea, a temporary outdoor exhibition first held in 1997 along the coastal walk between Bondi and Tamarama.

The idea was deceptively simple: place contemporary sculptures along a cliffside path and allow the landscape to shape their meaning. But the effect was transformative. The event turned Sydney’s most iconic natural feature—the coastline—into a public gallery, free and physically immersive. It invited families, tourists, critics, and passersby to engage with contemporary art without stepping into a museum.

The works ranged from monumental installations to subtle interventions. A polished steel ring framing the sea horizon. A twisted figure emerging from the sand. A field of concrete houses balanced on spindly legs. Some works were whimsical, others grave. All were made to be walked around, touched, and seen in shifting light.

What began as an experiment quickly became a civic ritual. Sculpture by the Sea drew massive crowds and, over time, growing institutional support. But it also provoked debate about the line between spectacle and substance. Were these works genuinely challenging, or merely decorative? Did they advance sculpture as an art form, or dilute it into entertainment?

Such questions are not easily resolved. But the event’s success showed that Sydney had developed an appetite for public art that was not confined to bronze statues or war memorials. It wanted art in motion, in weather, in space.

More importantly, it marked a conceptual shift: public art was no longer something erected by the state to signify consensus. It could now be temporary, provisional, and varied. It could reflect private visions in public places. It could speak to delight, confusion, disagreement, or awe.

In this sense, the postwar boom in Sydney’s public art did more than decorate the city. It changed how the city thought about itself—who it was for, how it should be remembered, and what kinds of beauty it could hold in common.

Aboriginal Art in Sydney: From Obscurity to Major Collections

For much of the 20th century, Aboriginal art was systematically excluded from Sydney’s galleries, museums, and art schools—not because it was unknown, but because it was misunderstood. It was treated as ethnography, not aesthetics; as craft, not culture; as relic, not relevance. But beginning in the 1970s and accelerating into the 21st century, this exclusion began to erode. Today, Aboriginal art is one of the most vital forces in Sydney’s cultural life—not only visible in collections and exhibitions, but recognised as central to the story of Australian art itself.

The Papunya Movement’s Impact on Sydney Audiences

The shift began, improbably, in a remote desert town over two thousand kilometres from Sydney. In 1971, a group of senior Aboriginal men at Papunya, in the Northern Territory, began painting stories of their Dreamings using acrylics and boards—adapting ceremonial motifs to new materials with the guidance of art teacher Geoffrey Bardon. The results were electrifying: dense, intricate fields of dots, lines, and symbolic forms that held layers of cultural knowledge and ancestral narrative.

These early Papunya boards reached Sydney slowly, through dealers and curators who recognised their artistic power but were often unsure how to present them. At first, they were shown in anthropology museums, accompanied by cautious labels and apologetic explanations. But by the 1980s, major institutions—including the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW)—began acquiring them as works of art, not as cultural curiosities.

The 1984 exhibition Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, though organised by the Asia Society in New York, had a significant impact on Australian audiences when it toured domestically. For many Sydneysiders, it was the first time Aboriginal art had been framed as contemporary, not “traditional”—living, experimental, and engaged with the wider world. A rethinking had begun.

Yet even as the desert painting movement gained attention, urban Aboriginal artists in Sydney were developing a very different approach—one grounded not in dot painting or sacred topographies, but in the politics of representation, memory, and survival.

Urban Aboriginal Artists: Gordon Bennett, Fiona Foley, and the Question of Identity

In the 1990s, a generation of urban Aboriginal artists emerged who rejected the notion that Aboriginal art must conform to a particular look or lineage. They worked in photography, installation, video, and conceptual media—often blending Indigenous imagery with European art history, colonial archives, or popular culture. Their work addressed not only cultural continuity, but rupture: the violence of colonisation, the legacy of dispossession, the construction of identity under surveillance.

Gordon Bennett, though based in Brisbane, exhibited widely in Sydney and profoundly influenced the city’s art discourse. His paintings layered Aboriginal motifs with quotes from European modernism—Picasso, Mondrian, Malevich—forcing viewers to confront the contradictions of a culture built on both admiration and erasure. In works like Possession Island (1991), he reimagined Captain Cook’s arrival through the fractured lens of Aboriginal displacement, using painterly techniques to expose historical amnesia.

Fiona Foley, born in Queensland but long active in Sydney’s institutions, created installations and photographic series that explored gender, race, and public memory. Her work Edge of the Trees (1995), made in collaboration with architect Richard Johnson, stands outside the Museum of Sydney. It consists of 29 vertical poles—some of them inscribed with Aboriginal place names, others with the names of early settlers. Visitors can hear recorded voices speaking in Indigenous languages. The piece is not a monument but a site of encounter, where past and present are layered together.

These artists—along with Brook Andrew, Rea, Jonathan Jones, and many others—rejected the idea that Aboriginal art should be frozen in a symbolic past. Their work was contemporary, confrontational, and often uncomfortable. It demanded space not just on gallery walls, but in public debate.

Sydney, with its concentration of institutions, collectors, and media, became a key stage for this artistic redefinition. Biennales, solo exhibitions, and institutional commissions all began to feature Indigenous perspectives—not as gestures of inclusion, but as leading voices.

Curatorial Shifts and Aboriginal Representation in Major Galleries

The institutional landscape began to change in the early 2000s. The Art Gallery of New South Wales, long criticised for its cautious approach to Aboriginal art, established a dedicated curatorial department for Indigenous works. It began acquiring major pieces from both remote and urban artists, staging exhibitions that treated Aboriginal art as part of the national contemporary story—not as a sidebar or exception.

One major milestone came in 2010, when the AGNSW unveiled its Yiribana Gallery, a permanent space devoted to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art. The name, meaning “this way” in the Sydney language, signalled a new direction—not just in display, but in institutional philosophy. The gallery brought together bark paintings from Arnhem Land, desert canvases, urban photo-media, and political installations. It presented diversity without hierarchy.

This curatorial shift was mirrored by other Sydney institutions. The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) began commissioning major works by Aboriginal artists, including site-specific installations by Daniel Boyd, Judy Watson, and Maree Clarke. These exhibitions were not framed as “Aboriginal shows,” but as part of the museum’s core program. They drew large audiences and critical acclaim, helping to normalise Indigenous perspectives within the mainstream.

At the same time, questions of governance and control became more urgent. Who tells the story of Aboriginal art? Who decides what is acquired, how it is shown, and to whom it belongs? These questions led to deeper consultation with communities, the employment of more Aboriginal curators, and the development of ethical protocols for acquisition and exhibition.

The shift has not been without tension. Debates continue over appropriation, overrepresentation, and the commodification of sacred designs. Some Aboriginal artists refuse to show in major institutions, citing historical grievances and contemporary exclusions. Others see engagement as essential—a way to assert presence within structures that once ignored or marginalised them.

What is clear is that Sydney is no longer a city where Aboriginal art is confined to the margins. It is collected at the highest level, taught in universities, debated in journals, and seen by millions. It is both tradition and experiment, ceremony and critique.

The transformation has been slow and often contested. But it is visible—in the works themselves, in the names on the wall, and in the kinds of questions now asked. The oldest art in Sydney may be carved into stone, but its most urgent art today continues to carve into the conscience of the city.

The Biennale and the International Stage: Sydney as Art Capital

By the late 20th century, Sydney’s cultural ambitions had outgrown its colonial past, its provincial rivalries, and even its national context. The city no longer merely received exhibitions from abroad—it began to generate them. The launch of the Biennale of Sydney in 1973 marked a critical shift: for the first time, Australia positioned itself within the global network of contemporary art. The Biennale did not just bring the world to Sydney; it challenged Sydney to respond, to innovate, and to define its place in the international conversation. The results were sometimes controversial, often uneven, and always revealing.

The 1973 Biennale and the Whitlam-Era Cultural Push

The inaugural Biennale of Sydney opened in September 1973—just weeks before the official opening of the Sydney Opera House. It was a moment charged with symbolism: the arts had arrived, not as colonial adornment, but as public commitment. Under the reformist government of Gough Whitlam, federal cultural funding increased dramatically, supporting not only institutions but experimental initiatives. The Biennale was one such project, made possible by a combination of federal grants, private sponsorship, and the efforts of visionary organisers like Anthony van Dyck and Nick Waterlow.

The first edition, titled Project 1: The Biennale of Sydney, featured artists from over 30 countries and was installed at the Sydney Opera House, still smelling of fresh concrete and political optimism. The works ranged from kinetic sculptures to conceptual installations, with an emphasis on new media, participatory work, and radical aesthetics. It was the first exhibition in Australia to treat contemporary international art not as foreign import, but as shared terrain.

Over the following decades, the Biennale expanded in scale and complexity. It took place in multiple venues across the city—the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Pier 2/3, and later Cockatoo Island—each iteration redefining the physical and conceptual map of art in Sydney. Under directors such as Leon Paroissien, Bernice Murphy, Isabelle Graw, and Juliana Engberg, the Biennale embraced installation, performance, video, and cross-cultural dialogue. Its themes grew more ambitious: identity, migration, language, conflict, the Anthropocene.

The Biennale helped transform Sydney’s art scene from an introspective, regionally focused network into a porous, globally aware arena. Local artists showed alongside international figures. Emerging curators worked with visiting institutions. The line between Australian and global began to blur—not through assimilation, but through encounter.

Performance, Protest, and Site-Specific Experimentation

From its earliest editions, the Biennale encouraged artists to respond not only to their themes, but to the city itself. Site-specific works became central to its identity—not just because of logistical necessity, but because Sydney offered a dramatic physical context: harbourside warehouses, decaying naval buildings, sandstone quarries, and even abandoned power stations. These spaces allowed artists to engage directly with history, scale, and atmosphere.

One of the most transformative venues was Cockatoo Island, first used in the 2008 Biennale under curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. The island’s layered history—as penal colony, shipyard, and military base—infused the works with an eerie gravity. Artists installed monumental video pieces in rusted warehouses, suspended sculptures from derelict cranes, and filled concrete bunkers with sound and shadow. The venue became a work in itself—a charged site where memory and material collided.

The Biennale also became a space of political performance and protest. In 2014, several artists withdrew from the exhibition in protest against its principal sponsor, Transfield Holdings, a company linked to the management of offshore immigration detention centres. The controversy ignited a national debate about ethics in arts funding, prompting the Biennale’s board to sever ties with Transfield. The episode marked a turning point: the Biennale was no longer just an artistic platform. It was a public institution, expected to account for its partnerships and values.

Performance art, too, found fertile ground in Sydney. Works by artists such as Mike Parr, Marina Abramović, and Tino Sehgal transformed exhibition spaces into zones of interaction, confrontation, and ephemerality. In these works, the body became both subject and site—asking audiences not just to look, but to participate.

These experiments altered the expectations of Sydney audiences. Art was no longer confined to canvases or objects. It could be time-bound, fragile, and relational. It could unfold on stairwells, in car parks, or under bridges. It could whisper or shout.

Internationalisation and Critique: Evolving Curatorial Roles

As the Biennale grew, so too did the scrutiny surrounding its choices. Who was invited? Who was left out? What narratives were being privileged? These questions became central not just to the exhibitions themselves, but to the broader discourse around cultural institutions in Sydney.

Curators, once invisible, became visible—and occasionally embattled—figures. Their selections shaped reputations, careers, and the intellectual tone of the event. Some editions, like Okwui Enwezor’s 2006 Biennale, were praised for their intellectual rigour and geopolitical scope. Others were criticised for vagueness, insularity, or thematic excess. The very ambition of the Biennale became part of its vulnerability.

Sydney’s art community, meanwhile, became more assertive. Critics, artists, and viewers demanded representation not only from Europe and North America, but from the Pacific, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. The city’s own demographics—marked by migration and cultural plurality—pushed institutions to rethink their global imaginary. It was no longer enough to invite the usual circuit of Western conceptualists. The international stage had to mean more than geography. It had to mean complexity.

The Biennale responded with varying success. Some editions embraced collaborative curating, working with artists as co-shapers of the exhibition. Others leaned into themes like superposition (2018) or rīvus (2022)—exploring ideas of quantum multiplicity or water as political matter. These curatorial frameworks often stretched interpretation, but they also reflected a willingness to take risks.

At its best, the Biennale has made Sydney a laboratory for experimentation: a place where local and global ideas collide, not to resolve, but to evolve. It has exposed audiences to challenging work, brought under-recognised artists into view, and expanded the language of what public art can be.

Yet it remains contested ground. No single exhibition has satisfied all expectations. Nor should it. The Biennale’s value lies in its restlessness—in its refusal to settle into comfort or consensus.

Sydney may not yet rival Venice or Kassel in institutional legacy. But it has something different: a city where art meets landscape, history, and contradiction. A city that asks questions without pretending to finish the answers.

Architecture as Art: The Sydney Opera House and Beyond

For many cities, architecture frames the experience of art; in Sydney, one piece of architecture became the experience. The Sydney Opera House, completed in 1973 after decades of design controversy, cost overruns, and political fallout, is more than a concert hall or visual landmark. It is a sculptural gesture on a monumental scale—an artwork in itself, and perhaps the most enduring example of architecture as cultural vision in Australia. But the Opera House was not the end of architectural ambition in Sydney. In the years that followed, the city would see public buildings, infrastructure, and private developments reimagined with aesthetic intent, testing the boundaries between utility and expression.

Jørn Utzon’s Landmark Design and Its Challenges

The story of the Opera House is so often retold that its outlines can feel mythic: Danish architect Jørn Utzon, a relatively unknown figure at the time, wins an international competition in 1957 with a design that defies conventional engineering and aesthetic norms. His scheme—soaring white shells clustered at the edge of Bennelong Point—was unlike anything else submitted. It was daring, sculptural, and at the time, unbuildable.

Over the next sixteen years, the building became a lightning rod for debate. Structural engineers struggled to translate Utzon’s organic forms into load-bearing realities. The project’s budget exploded, from an initial estimate of $7 million to over $100 million by the time it opened. Political pressure mounted. In 1966, before the structure was complete, Utzon resigned under duress and left the country. He would never return to see the building finished.

Despite these fractures—or perhaps because of them—the Opera House achieved something extraordinary. It redefined not just Sydney’s skyline, but Australia’s cultural identity. Its design blurred the lines between architecture, sculpture, and stagecraft. With its interlocking vaults and reflective tiles, the building responded to both sea and sky, turning the act of arrival into a kind of pilgrimage.

Critics at the time were divided. Some saw it as an extravagant folly, a symbol of dysfunction. Others, especially after its completion, recognised its lasting influence. The Opera House was not just a home for the arts—it was a statement that the city itself could be part of the performance.

In 2003, four decades after his resignation, Utzon was invited to oversee a redesign of the interior spaces. He contributed remotely from Denmark, working with his son and a new team of architects to bring the building closer to his original vision. In 2007, the Opera House was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site—cementing its place in global architectural history.

Integrating Visual Art into Public Buildings and Spaces

The Opera House may be singular, but it triggered a broader shift in how Sydney thought about the relationship between form and function. Public architecture was no longer expected to merely house activity; it was expected to express it.

In the decades following its completion, public buildings began to incorporate visual art directly into their design. The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), opened in 1991 in a repurposed Art Deco maritime building, expanded in 2012 with a new wing that integrated digital screens, sculptural facades, and a dynamic rooftop venue. The building became a visual signal in itself—foregrounding art not just inside, but in its very surfaces.

Government infrastructure also adopted an aesthetic role. Sydney’s rail stations, motorways, and airport terminals began to include site-specific installations, mosaics, and light-based works. Some of these were integrated from the planning stages; others were retrofitted, part of a growing belief that public space could—and should—be visually alive.

One example is the Eora Journey, a city-backed initiative that aims to integrate Aboriginal history and art into the fabric of central Sydney. Projects under this program have included large-scale light projections onto public buildings, sound installations along walking routes, and permanent sculptures that reference Indigenous stories and landmarks. Rather than isolate art in designated “cultural zones,” these works seek to embed it into the city’s daily flow.

Another development is the use of translucent façades and green infrastructure in civic buildings—where the surface of a library, school, or hospital becomes part of the urban aesthetic. In many cases, architects collaborate with artists from the outset, blurring traditional divisions of authorship. The result is not always successful, but it reflects a growing recognition that civic identity is visual as well as functional.

Private developments, too, have embraced architectural spectacle. Towers by firms like FJMT, PTW, and Renzo Piano Building Workshop have altered the city’s skyline, often with art commissions embedded in lobbies, foyers, or external plazas. These gestures are not purely altruistic—developers recognise the cultural cachet of visible art—but they contribute, for better or worse, to the city’s evolving visual ecology.

Barangaroo and the Aestheticisation of Sydney’s New Waterfront

No project better illustrates the entanglement of art, architecture, and urban ambition than Barangaroo, the massive waterfront redevelopment just west of the central business district. Spanning over 22 hectares, it includes parks, office towers, luxury apartments, cultural venues, and retail spaces—presented as a model of sustainable urban design and economic growth.

From its inception, Barangaroo was promoted as an “urban canvas.” Public art was written into the master plan, with commissions from artists such as Yhonnie Scarce, Brook Andrew, and James Carpenter. The Barangaroo Reserve, a parkland created from reclaimed industrial land, incorporates sandstone terraces, native plantings, and pathways named after local Indigenous languages and leaders. Sculptural elements are embedded throughout, sometimes subtly, sometimes with assertive presence.

But the project has also drawn criticism. Some see it as the epitome of corporate-led gentrification: a place of curated culture, architectural polish, and social exclusion. The public art, critics argue, risks becoming decoration—used to soften the hard edges of development rather than challenge its assumptions.

Even so, Barangaroo marks a new phase in Sydney’s architectural self-image. The city no longer builds monuments alone. It builds environments—complex spaces where art, commerce, history, and spectacle are entangled. In this model, architecture is not just a background for culture. It is part of culture, inseparable from the stories it enables or displaces.