The founding of Savannah in 1733 was not merely an act of colonization—it was a feat of design, drafted with the confidence of a draughtsman and the conviction of a utopian. Few cities in North America were conceived so explicitly as a visual composition. Before brush met canvas or chisel met stone, Savannah was art: a rational, geometric plan carved into the wilderness with paper, ink, and ideology.

The 1733 Oglethorpe Plan and urban geometry as aesthetic expression

General James Oglethorpe’s plan for Savannah was a grid, but not just any grid. It was modular, cellular, almost organic in its repetition. Known now as the Oglethorpe Plan, it divided the city into a series of wards, each organized around a central square. These wards were not passive blocks of real estate—they were the living organs of a social theory rendered visible.

Each square was flanked by trust lots (for public buildings) and tythings (for private dwellings), in a layout that promised equality and order while subtly maintaining hierarchy. In an era when European cities grew chaotically from medieval roots, Savannah’s plan stood apart as something shockingly modern: Enlightenment spatial philosophy given physical form.

Oglethorpe’s motivations were as much aesthetic as they were moral and military. He believed that regularity fostered virtue, that beauty and good government were entwined. The city’s pattern was meant to balance individual liberty with communal responsibility—every inhabitant would live near a square, which was both green commons and stage for civic life. In its symmetry and scale, the plan resembles not a battlefield or plantation, but a painting: framed, composed, controlled.

This rational clarity impressed itself on artists and visitors for centuries. John Berendt, author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, called Savannah “a jewel-box city.” But its jewel-box quality was no accident. It was a visual program, and it began with the map.

Gridlines and gardens: Enlightenment ideals in city form

The squares, eventually totaling twenty-four (twenty-two survive), were designed not only for practical defense or real estate development. They were conceived as aesthetic pauses—horticultural reliefs in a sea of masonry. With live oaks, palmettos, flowering shrubs, and formal paths, each square became its own pocket universe, a miniature Eden curated by gardeners, architects, and eventually city planners.

These weren’t merely pleasant places to sit. They embodied an Enlightenment impulse to rationalize and beautify nature. In that sense, Savannah was part of a broader Atlantic-world project. While French architects imposed grand axial designs in Paris and English landscape gardeners sculpted their groves, Savannah’s planners made a grid that framed beauty in manageable pieces.

This was not just visually pleasing—it was morally charged. A neat city was a virtuous city. A walkable, green city was a civilized one. This belief, inherited from British urban reformers and ancient Roman ideals, made its way into every path and plot.

Yet Savannah’s plan also bore a quiet violence. Native lands were cleared, swamps were drained, and enslaved Africans built the city’s bones. The design’s visual order often masked the brutal inequalities that underpinned it. Even its most charming vistas were formed under conditions of unfreedom.

Still, the aesthetic experience endured. Travelers arriving by ship in the 18th and 19th centuries consistently described the city as beautiful in its uniformity—where each square opened onto an axis of tranquility and framed sightlines drew the eye into calm. In an age before zoning laws, Savannah’s plan was itself a kind of artistic regulation.

Architecture as visual order and moral metaphor

The buildings that rose within the Oglethorpe Plan followed its cues. Early structures were simple: timber-framed houses, tabby concrete, modest churches. But as the city’s wealth grew, especially through rice and cotton, more elaborate architectural styles arrived—Georgian, Federal, Greek Revival, Gothic.

Even as styles changed, the commitment to visual harmony remained. Strict height limits were observed. Setbacks were enforced. Porticoes, wrought-iron balconies, and pastel stucco facades became motifs of a local aesthetic that prized restraint over ostentation.

One telling example is the Owens-Thomas House, designed in 1816 by English architect William Jay. Though a product of Regency England, the house fits perfectly into Savannah’s visual code: symmetrical façade, formal garden, and delicate ironwork that frames rather than flaunts. Its elegance is undeniable, but it does not dominate the square—it harmonizes with it.

This architectural cohesion turned Savannah into a kind of open-air gallery. Walking through its historic district is less like navigating a typical American city and more like leafing through a folio of engravings. Every block presents a new composition of light and shadow, column and arch, tree and square.

In the 20th century, preservationists recognized what had long been obvious to painters and photographers: Savannah’s visual order was rare and fragile. Their campaigns to save entire neighborhoods from demolition or modern encroachment were driven by a belief in the city as aesthetic artifact. The founding of the Historic Savannah Foundation in 1955 was not just a heritage movement—it was an artistic one.

That conviction continues to shape how the city is viewed, photographed, drawn, and sold. Postcards and posters, tourist brochures and film locations—Savannah’s image remains that of a painted city, carefully arranged. And while its contradictions—between surface and history, form and labor—are real and unresolved, they only deepen the strange beauty of its design.

Sacred Paint and Pine: Early Religious Art in Colonial Georgia

Long before Savannah became synonymous with wrought-iron balconies and Beaux-Arts mansions, its artistic life was kindled by something far more austere: religious necessity. In a city built on Enlightenment grids but peopled by exiles, missionaries, and pietists, early visual culture emerged from chapels and cemeteries, not drawing rooms. These were not sites of aesthetic luxury but of devotional intensity, where art was enlisted in the service of spiritual discipline and salvation.

The visual language of Anglican and Moravian missions

When the first colonists arrived with James Oglethorpe in 1733, they brought Anglicanism with them—but theirs was a Church of England still wary of visual excess. Georgian Anglicanism, shaped by anti-Catholic sentiment and Protestant restraint, did not encourage grand altarpieces or gold-leaf icons. Instead, religious art was understated, moralistic, and often textual. Painted boards with scripture verses, carved pulpits, and the architectural clarity of meetinghouses dominated early Anglican interiors. In Savannah’s Christ Church, the city’s first parish, decoration took a back seat to didactic function.

But not all groups shared that visual reticence. The Moravians—German-speaking Protestants from Central Europe who arrived in Savannah in the 1730s—practiced a far more emotive Christianity. Though short-lived in Georgia, their presence left a subtle imprint. Moravian devotional aesthetics included small, emotionally intense engravings, illustrated hymnals, and carved devotional figures known as Herrnhuter. Their chapels, while plain on the outside, often concealed intricate symbolic programs that guided worship through visual meditation.

These influences converged in an environment of scarcity. There were few trained artists, fewer imported works, and little funding. Yet faith, as it often does, found form anyway—on hand-carved crosses, painted gravestones, and vernacular altars. Pinewood, clay, and lime wash became the materials of sacred imagination. This was not the flamboyant religiosity of Rome or Seville, but a whispered visual theology shaped by exile, perseverance, and the harsh light of coastal Georgia.

Iconography in early chapels and cemeteries

If Savannah’s early churches were visually modest, its cemeteries spoke more boldly. Colonial burial grounds, like those at Colonial Park Cemetery, became some of the city’s first truly public visual spaces. Here, religious imagery mingled with memento mori, and stonecarvers—often anonymous—crafted symbols that walked the line between warning and comfort.

Gravestones from the mid-to-late 18th century often bore winged skulls, hourglasses, and weeping willows—icons of death drawn from Puritan, Anglican, and continental Protestant traditions. But in Savannah, these images took on a particular poignancy. Many graves belonged to children, felled by yellow fever or dysentery, and their epitaphs became miniature poems of grief. These stones were not merely functional—they were sculptural acts of remembrance. Their weathered surfaces, often locally quarried, took on a painterly patina in the humid climate, turning death into a kind of folk art.

One of the most striking examples is the headstone of Noble Wimberly Jones, a Revolutionary figure whose tomb features a carved urn and drapery motif—neoclassical symbols of civic virtue and mourning. Such motifs, adapted from European funerary sculpture, filtered into Savannah through engravings and pattern books, then translated by local artisans into a uniquely Southern idiom.

It is also here, among the tombs, that one begins to see the ghostly fusion of African and European funerary practices—a fusion that would grow stronger in the 19th century but had its visual roots in the quiet spaces of colonial death. The arrangement of graves, the placement of offerings, the persistence of certain carved motifs: these hinted at a spiritual cosmology not fully Anglican, not fully European, but wholly Georgian.

Craft, belief, and the theology of ornament

To understand early religious art in Savannah, one must look not just at finished objects, but at the spaces in which they were made and used. Many of the city’s earliest chapels and meetinghouses were constructed by congregants themselves, and in some cases by enslaved artisans whose labor was both skilled and invisible. In this world, ornament was not an indulgence—it was a coded form of worship.

A hand-planed pew, smoothed with obsessive care; a hand-forged candlestick bracket, curled just slightly into a stylized vine—these were acts of devotion. Their makers did not necessarily think of themselves as artists, yet they infused their work with meaning that exceeded function. These gestures, often overlooked in formal accounts of art history, shaped the spiritual experience of early Savannah as surely as any sermon.

Consider the case of the Independent Presbyterian Church, whose original 1750 structure featured a pulpit carved in mahogany, imported from the Caribbean. Though destroyed and rebuilt multiple times, the church’s visual sensibility remained tethered to a theology that embraced proportion, clarity, and scriptural centrality. The sanctuary’s painted panels, later added in the 19th century, continued this tradition—calm, symmetrical, and rich in metaphor.

Perhaps more revealing are the household religious objects that survive in archives and collections: fraktur-style baptismal certificates, hand-copied Psalters, and needlepoint samplers stitched with Biblical scenes. These small-scale works, often made by women or children, formed a kind of domestic sacred art. They were rarely signed or exhibited but were intimate, theological, and deeply visual.

In these fragments—pine benches, grave markers, wall panels—Savannah’s earliest religious art can be glimpsed not as a grand tradition, but as a fragile patchwork. Its aesthetic was one of necessity and belief, shaped by scarcity, humility, and hope. That legacy, though often invisible amid the city’s later grandeur, laid the emotional groundwork for everything that followed. The sacred pine gave way to the oil canvas, but it did not vanish. It simply changed its clothes.

Portraits in the Port: Eighteenth-Century Identity and Art Patronage

Before Savannah had galleries, it had parlors. Before it had schools of painting, it had porticos where sitters posed stiffly for visiting artists. The eighteenth century in Savannah was not yet a period of flourishing local talent, but it was a period of strategic self-fashioning—one in which landowners, merchants, and newly arrived families used portraiture to assert identity, display wealth, and anchor themselves in the social fabric of a fragile colonial outpost. In a city dependent on Atlantic trade, portraiture functioned not only as art, but as evidence: of lineage, loyalty, literacy, and power.

Savannah’s planter elite and their imported painters

In the decades after its founding, Savannah grew from an experimental buffer colony into a port city with ambitions that exceeded its frontier status. Cotton had not yet become king, but rice and timber built fortunes, and with wealth came an appetite for culture—especially the kind that could be hung above a fireplace.

Savannah’s elite families, many of them originally from the British Isles or the West Indies, quickly absorbed the portrait traditions of the Anglo-American world. These were not cosmopolitan collectors, but they understood the value of having one’s likeness recorded by a trained hand. At first, this meant relying on itinerant artists—often European-trained, sometimes self-taught—who moved along the Atlantic seaboard offering their services to the well-positioned.

One of the earliest known portraitists to work in the region was John Wollaston, an English painter who arrived in the colonies around 1749 and left behind a trail of remarkably consistent likenesses. His sitters, found in Virginia, Maryland, and South Carolina, appear in Savannah records by the 1750s. Wollaston’s portraits are instantly recognizable: elongated oval faces, almond-shaped eyes, and a slight detachment that reads more as idealization than intimacy. His style suited his clients. They didn’t want psychological realism—they wanted social confirmation.

After Wollaston came Henry Benbridge, another British-American painter whose neoclassical training brought a more refined, continental elegance to Southern portraiture. Though Benbridge was based primarily in Charleston and Philadelphia, his influence reached Savannah, and his patrons included men who treated the colonies as extensions of British gentry life. Their portraits, in powdered wigs and embroidered waistcoats, were aspirational documents. In them, Savannah emerges not as a raw outpost, but as a place of order and rank.

These commissions were more than decorative. They were visual contracts—declarations of cultural belonging. To hang a Benbridge or a Wollaston in one’s home was to assert one’s place in the Atlantic hierarchy of taste and power.

Faces of power: John Wollaston and Henry Benbridge’s commissions

Many of these portraits survive today in the collections of the Telfair Museums and regional historical societies. They offer a vivid window into the aspirations of early Savannah society. Take, for instance, the 1750s portrait of Mary Jones Bulloch, attributed to the Wollaston circle. She is seated in silk, her hand resting on an embroidered tablecloth, her gaze serene but remote. There is no background narrative, no domestic setting—only a timeless void that enhances her status and removes her from the flux of everyday life.

Or consider the depiction of Joseph Clay, a British merchant and later a Revolutionary patriot, whose likeness reveals the shift from imperial loyalty to colonial self-possession. These portraits are not vivid character studies in the modern sense. Their strength lies in their stiffness. The artificiality is intentional; it is the language of status, and it was understood as such by artist and client alike.

By the 1770s, portraiture in Savannah had become both fashionable and politically charged. The American Revolution complicated the allegiances that earlier portraits had so carefully encoded. Some families who had commissioned likenesses in full British regalia found themselves on the side of rebellion; others fled the city altogether during its brief period under Loyalist control.

This period also witnessed the emergence of homegrown talent. A handful of Savannah-born artists began to experiment with portraiture using imported pigments and copied engravings as their guides. Though technically crude by academic standards, these portraits—many unsigned—offer an alternate visual record, one that suggests a quiet, emerging vernacular distinct from imported styles.

Oil on canvas in a slave economy

Savannah’s portraits cannot be fully understood without reckoning with the economy that funded them. The city’s rise coincided with the entrenchment of slavery, and many of the sitters who appear in these works—draped in lace, adorned with pearls—derived their wealth from enslaved labor. Portraiture in this context was not merely about beauty or lineage. It was a mechanism for laundering violence into gentility.

Some artists, particularly those with European training, may have felt unease about this. Others saw it as irrelevant. In either case, few depictions of enslaved people appear in Savannah’s eighteenth-century portraiture, and when they do, they follow strict pictorial codes. A servant might appear in the background, gaze averted, often rendered with less precision than the sitter’s silks or hair. These inclusions served as visual footnotes to the wealth and station of the primary subject. They were not portraits—they were accessories.

And yet, the absences are just as telling. The complete omission of Black bodies from many domestic portraits was itself a statement: an effort to naturalize a social order without showing its machinery. This erasure extended even to the craftsmanship. Enslaved artisans—some of whom likely helped construct the homes in which these portraits were displayed—are never credited. Their work supported the aesthetic stage upon which these likenesses were installed.

This silence would eventually rupture, but in the eighteenth century, it held. Savannah’s early portraiture tells us much about aspiration and self-image, but its greatest eloquence may lie in what it refuses to depict.

By the dawn of the nineteenth century, the city was no longer an experiment but an established Southern port. Its portraits had grown larger, more ambitious, more confident. They hung in townhouses on Bay Street and in plantation halls along the river. They watched over tea tables, marriages, and funerals. They created a kind of haunted permanence—faces stilled in the oil-light of empire, posing for a future that had already begun to shift beneath their powdered skin.

Art of Conflict: Visual Culture of Revolution and Secession

Savannah’s visual identity was forged not only in quiet parlors and shaded squares, but in the fury of ideological upheaval. The American Revolution and the Civil War did not merely disrupt the city’s civic life—they redefined its symbolic vocabulary. Across flags, prints, murals, monuments, and ephemera, Savannah’s art became a field of rhetorical battle, a medium for forging allegiances and revising memory. The wars were waged with muskets and ink alike.

Prints, flags, and patriotic images before and after 1776

In the years leading up to the Revolution, Savannah was a hotbed of Loyalist and Patriot tension. Though not as iconographically saturated as cities like Boston or Philadelphia, Savannah still participated in the increasingly visual culture of rebellion. Broadsides, political cartoons, and engraved allegories circulated in portside taverns and private clubs, often imported via Charleston or Philadelphia. These printed materials were ephemeral by nature, but they carried enormous symbolic weight.

One striking example was the display of effigies during Liberty Pole rituals—public events in which colonial dissenters erected poles topped with flags or symbolic objects, sometimes accompanied by painted signs denouncing the Stamp Act or Parliament. These acts blurred the boundary between performance and visual art: a protest, yes, but also a choreographed, often hand-decorated tableau.

The Revolutionary period also saw the first flowering of symbolic flags in the region. The Liberty Flag, a variant of which was flown in Savannah, bore slogans and iconography drawn from Enlightenment and classical sources—snakes, trees, suns. These were not mass-produced items; each flag was, in essence, a painted statement, created by hand and raised in defiance. They were ephemeral paintings of allegiance.

The city’s shifting control during the war—occupied by the British from 1778 to 1782—further complicated its visual culture. British commanders brought their own symbols: regimental banners, formal portraits of the king, and military engravings shipped from London. After independence, these images were scrubbed or buried, replaced by portraits of Washington and allegorical prints celebrating liberty.

Even in a city with few formally trained artists, image-making mattered. The Revolution was as much a war of symbols as of arms, and Savannah’s port ensured that its residents were never far from the visual currents of empire and insurgency.

Antebellum murals and monuments as political messaging

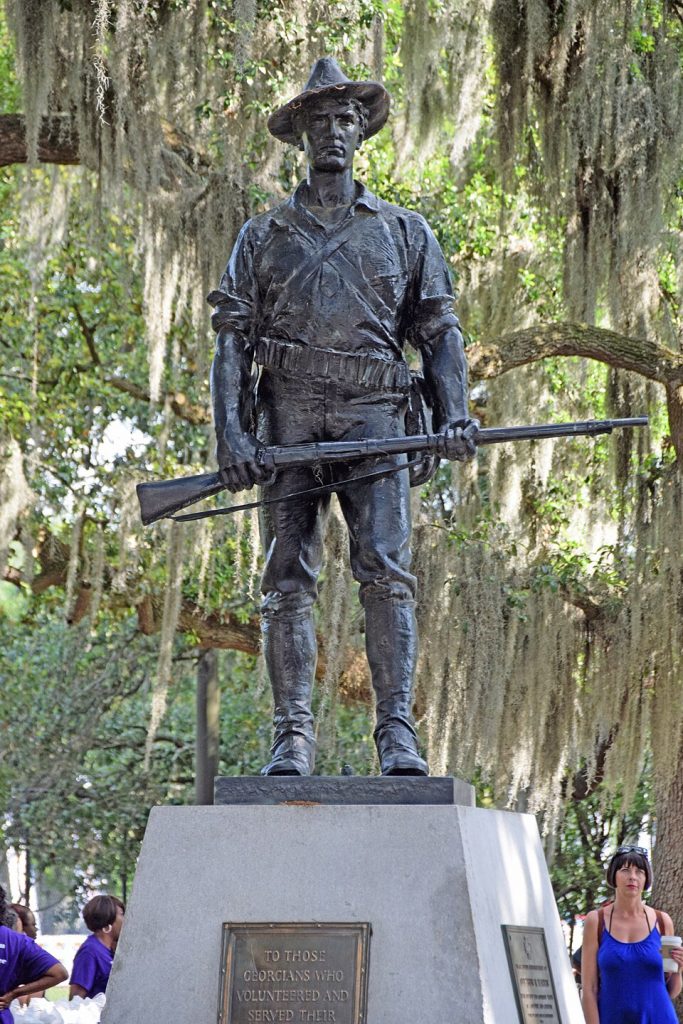

As the memory of the Revolution ossified into heritage, a new political crisis began to surface: sectionalism. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Savannah’s leading families began to see themselves not just as Americans, but as Southerners with a distinct, embattled cultural identity. This identity found form in statuary, architecture, and a newly monumental public art.

One of the earliest and most enduring examples was the Pulaski Monument, dedicated in 1855 to General Casimir Pulaski, the Polish nobleman who died at the Siege of Savannah in 1779. Designed by Robert Launitz in the neoclassical style, the monument occupies Monterey Square and reflects both Revolutionary reverence and antebellum self-regard. Its clean marble lines and heroic inscriptions present a sanitized vision of sacrifice, free of the messy racial and political complexities that defined the city’s present.

Inside private homes and elite institutions, murals began to appear, often allegorical and overtly political. Scenes of Southern agriculture—white-robed figures harvesting cotton under golden skies—were painted onto parlor ceilings and dining room walls. These were not innocent depictions of toil; they were ideological images, meant to naturalize slavery as pastoral and eternal.

By the 1850s, as secession loomed, Confederate symbology began to seep into local iconography. While overt propaganda was rare before Fort Sumter, the visual grammar of grievance—classical ruins, wounded veterans, maternal allegories of “the South”—had begun to form. Painters and printers who once produced landscapes or portrait miniatures began to pivot toward cause-making. Visual art became preparation for war.

Savannah, though more conservative than Charleston, mirrored these shifts. Its art did not yet rage—it sighed, longed, and mythologized. This restraint made the eventual rupture all the more devastating.

Artistic echoes of disunion: allegory, martial painting, and ruin imagery

When war finally came in 1861, the Southern visual imagination ignited. Flags, seals, and printed propaganda proliferated. Savannah’s contribution included engraved Confederate banknotes, hand-sewn regimental banners, and wartime photographs—some posed, some documentary. The Savannah Republican and other papers printed patriotic engravings and lithographs, many drawn from European models but imbued with local color.

At the same time, more personal forms of visual expression emerged. Soldiers’ sketchbooks from the period show crude but poignant attempts to depict battles, encampments, and memories of home. In letters and diaries, amateur drawings accompanied words—a visual parallel to emotional desperation.

One notable moment in Savannah’s wartime visual culture came not from creation, but from destruction. When General William T. Sherman’s Union forces marched into Savannah in December 1864, they found a city largely intact—Sherman had spared it from burning. But the threat of ruin hovered over every square, every church steeple. Artists in the North seized on this paradox. Lithographs showed a dreamy, intact Savannah, sleeping in the path of devastation. Southern artists, meanwhile, began to embrace the motif of the noble ruin.

These images proliferated after the war: collapsing porticoes, shattered columns, overgrown gates. Sometimes literal, sometimes invented, they transformed the trauma of defeat into an aesthetic of melancholy grandeur. This visual mode—equal parts nostalgia and sublimation—would come to define the Lost Cause mythology. Savannah’s ruins became less about what had been lost, and more about what might yet be reclaimed, or remembered on its own terms.

One painter, George Cooke, though not native to Savannah, helped shape this visual lexicon with his romanticized Southern landscapes and architectural studies. His influence endured in the city’s postwar art, which often blurred the line between memory and fantasy.

What began as rebellion became elegy. In the aftermath of secession, Savannah’s artists turned away from overt political imagery and toward something more atmospheric—ruins, ghosts, and symbols stripped of clarity. It was no longer a time for portraits. It was a time for shadows.

Haunted Frames: Gothic Revival and Romanticism in Savannah

By the mid-19th century, Savannah no longer dreamed only of empire or revolt. It dreamed in shadows. While neoclassicism still ruled the facades of banks and mansions, a darker, more atmospheric sensibility took hold of the city’s visual imagination. In churches, cemeteries, and homes, the language of Gothic Revival and Romanticism flourished—not as foreign import, but as a native idiom. Savannah, with its humid decay and reverent quiet, seemed made for the Gothic long before it learned to speak it.

Ruins, weeping angels, and the Southern picturesque

Nowhere is Savannah’s romantic turn more visible than in Bonaventure Cemetery. Originally a plantation overlooking the Wilmington River, the site became a public cemetery in the 1840s and quickly transformed into an immersive landscape of grief. Its winding paths, live oaks draped in Spanish moss, and elaborate funerary sculpture made it a pilgrimage site for mourners, artists, and curious travelers. Even today, Bonaventure does not feel arranged—it feels composed.

The visual centerpiece of the cemetery was, and remains, its sculpture. Victorian mourning culture found full expression here: marble angels slumping in sorrow, obelisks breaking into the canopy, urns swaddled in drapery. These were not merely religious symbols—they were romantic allegories of memory, nature, and decay. They offered a pictorial theology in which death was not denied but beautified.

One of the most famous figures interred at Bonaventure is Gracie Watson, a six-year-old girl who died of pneumonia in 1889. Her grave features a life-size marble portrait, sculpted by John Walz, that captures her expression with unsettling accuracy. The statue, placed behind iron fencing, became an object of both reverence and tourism—a perfect artifact of Romantic morbidity. Tourists left offerings; locals told stories. Gracie became, in essence, an icon.

The Southern picturesque, as developed by artists and writers in this period, relied on just such images. Nature was not wild—it was sublime. Architecture was not ruined—it was dignified in decline. Savannah’s damp climate and slow pace made it a natural incubator for this vision. The city became not just a place to live, but a place to mourn beautifully.

Travelers from the North and Europe, visiting in the decades after the Civil War, often remarked on Savannah’s air of “gentle sadness.” Their sketches and journal illustrations reveal a consistent palette: bowed trees, ivy-covered gravestones, shadowed porches. The Gothic was not imported—it was ambient.

Bonaventure Cemetery and the sculptural poetics of grief

The sculptors who worked in Bonaventure were mostly regional artisans, often trained in stone yards or funeral workshops in Charleston, Augusta, or even New York. But they adapted their forms to local demand, creating a Southern Gothic vocabulary that was less theatrical than European cathedrals, more personal than academic monuments.

Three motifs dominated: the draped urn, the broken column, and the angel in repose. The draped urn symbolized the veil between life and death, often rendered in high relief on upright stones. The broken column signified a life cut short—a child, a young bride, a soldier lost. And the angel, usually female, mourned or gestured upward, embodying the Romantic ideal of death as transformation rather than cessation.

These forms were not static. Sculptors incorporated naturalistic details—palmetto fronds, dogwood blossoms, coastal birds. Names were carved in flourishes that bordered on calligraphy. These tombs were not only about death; they were about Savannah as a place of aesthetic farewell.

In this way, Bonaventure became both cemetery and sculpture park. The visual culture of mourning fed into the broader artistic ethos of the city. Painters, particularly those associated with the Southern Romantic tradition, found inspiration among the graves. Even writers took part: the language of marble, moss, and memory permeated the regional gothic literature that would later define the South.

This sculptural language also spread to religious architecture. Churches across the city adopted Gothic Revival elements: pointed arches, lancet windows, wooden vaulting. These were not always doctrinal choices—they were atmospheric ones. Parishioners entered a world of shadow and reverent geometry, designed not for instruction, but for awe.

Architecture as mood: Carpenter Gothic and Italianate façades

Beyond sculpture and tombs, the Gothic found expression in Savannah’s residential architecture. Especially in the mid-to-late 19th century, the Carpenter Gothic style—so named for its wooden adaptation of Gothic stonework—appeared in the city’s quieter wards. These were not grand mansions, but modest homes with steep gables, decorative bargeboards, and pointed window arches.

They stood apart from the symmetrical Federal and Greek Revival homes around them. Carpenter Gothic spoke a different language—of fantasy, of sentiment, of retreat. It turned the house into a poem.

Simultaneously, the Italianate style became popular among wealthier families, bringing with it tall windows, bracketed cornices, and cupolas. Though not Gothic in structure, Italianate homes shared the Gothic mood—evoking European nostalgia, cultivated melancholy, and a sense of historical layering. Savannah’s streets began to resemble a curated ruin: old-world elegance transplanted to subtropical soil.

This blend of styles produced a visual cityscape unique in the American South. Unlike Charleston’s colonial severity or New Orleans’ baroque flamboyance, Savannah embraced a quieter romanticism. The effect was cumulative. Walking the squares in 1880, one might pass from neoclassical order to Gothic whimsy to sculpted sorrow within three blocks. The city became a palimpsest of feeling.

That mood would not disappear with the century. It would become foundational to how Savannah imagined itself—and how others saw it. Even in the 20th century, when preservationists and artists turned their attention to the city’s heritage, it was the romantic image they sought to protect. The Gothic past was not a phase—it was a mirror.

Black Hands, Hidden Legacies: Enslaved and Freed Artists

The story of Savannah’s art has often been written in the names of donors, architects, and imported painters. But parallel to this official history—beneath the whitewashed walls and behind the carved doors—lies another tradition, one built with calloused hands and transmitted through craft, gesture, and memory. The artistic legacy of Savannah’s Black residents, both enslaved and freed, is vast yet largely uncredited, woven into the city’s ironwork, its vessels, its vernacular architecture. It is a visual history encoded in labor and disguised, for centuries, as mere function.

Vernacular craft traditions in ironwork, pottery, and wood

In antebellum Savannah, artistry did not always announce itself in frames or galleries. It appeared in gates and grates, in hinges and hearths. Black craftsmen—many enslaved, some free—were essential to the city’s visual fabric. Their names rarely appear in contracts or correspondence, but their work survives in form.

Take the wrought-iron balconies that curve over the streets of the historic district. Often attributed to white foundries or European design, many of these ironworks were in fact executed by enslaved artisans trained in blacksmith shops owned by white masters. These men were skilled in metallurgy, ornamentation, and technical precision, crafting scrollwork that fused West African symbolism with Anglo-American decorative trends. The repeating spirals, rosettes, and latticework of Savannah’s iron often contain rhythms—both visual and cultural—that echo across the Atlantic.

The same is true of Savannah’s pottery traditions. Edgefield stoneware, produced in upcountry South Carolina and traded through ports like Savannah, was largely made by enslaved potters. Among the most famous was Dave Drake, known as “Dave the Potter,” who inscribed verses onto jars and jugs despite the prohibition against enslaved literacy. While Drake’s work is rarely associated with Savannah directly, pieces from his circle passed through the city’s markets, and similar unnamed artists operated closer to the coast.

These utilitarian wares—jars, basins, storage vessels—were essential to plantation and domestic life. Yet they often featured subtle fluting, incised patterns, or hand-sculpted motifs. This quiet embellishment was not decorative excess; it was an assertion of agency. Every ridge and swirl was a mark of human presence in a system designed to erase it.

Woodwork also bore these fingerprints. Enslaved carpenters built much of Savannah’s early housing stock, especially the outbuildings, staircases, and interiors that escaped architectural attribution. Mantels, banisters, and molding often carry the stylistic signatures of West African carving traditions: symmetry with asymmetrical detail, symbolic notching, and repetitive geometric borders. Such marks, though seemingly ornamental, may have held deeper meanings—cosmological, mnemonic, protective.

These crafts were not marginal—they were central. They shaped the look and feel of the city. And though unsigned, they remain visible: in the sway of a railing, in the weight of a gate, in the touch-worn edge of a hand-planed door.

Quilts, carvings, and coded resistance

Beyond iron and wood, Black artistry in Savannah found voice in domestic and ephemeral forms—especially textiles and carvings. Quilting, long treated as a domestic chore, became a rich site of aesthetic and symbolic expression. In rural Georgia and coastal communities, quilt patterns like “Log Cabin,” “Flying Geese,” and “Drunkard’s Path” were passed down through generations of Black women. While some scholars have overstated their use as codes for the Underground Railroad, their visual significance is undeniable: they offered pattern, warmth, and identity in a world of disruption.

Savannah’s Black women, both enslaved and freed, participated in these traditions, often sewing by candlelight after hours of labor. Their quilts were rarely preserved by institutions, but some have survived in families or reentered public view through oral history projects. The act of quilting—precise, meditative, communal—was itself a resistance to silence, a refusal to let beauty be the domain of the privileged.

Carving, too, held power. Small devotional sculptures, cane heads, grave markers, and even carved toys have surfaced in archaeological and family contexts throughout the Lowcountry. These objects—some overtly Christian, others carrying Yoruba or Gullah echoes—formed an alternate canon of sacred art. They were not made to be exhibited. They were made to carry meaning.

Three such forms stand out:

- Carved walking sticks, often decorated with interlocking loops, heads, or animal motifs, acted as personal totems.

- Grave marker carvings, sometimes made from wood or shell, included faces, stars, and hands—symbols of passage and presence.

- Small domestic altars, sometimes built into cabin corners, combined Christian crosses with protective markings, salt dishes, or spirit bottles.

These works show a fusion of traditions, an improvisational theology built from available materials and inherited memory. They remind us that art, for the enslaved, was rarely about permanence. It was about presence. It was about marking a life where no name would be recorded.

Post-emancipation portraiture and visual assertion

After emancipation, Savannah’s Black residents began to engage more directly with visual self-representation. Freedmen and women sat for studio portraits, posed stiffly in their best clothes, asserting dignity through the format once reserved for the planter class. These tintypes and cabinet cards, often sold in bulk or mailed to family members, formed a new tradition: the democratization of portraiture.

In Savannah, Black photographers and photo studios began to emerge by the 1880s and 1890s, serving a growing Black middle class. While records are scarce, advertisements in Black-owned newspapers point to itinerant photographers and local operators catering specifically to African American clientele. These portraits often feature backdrops painted with neoclassical columns or rural scenes—visual echoes of white pictorial conventions, now repurposed to frame Black autonomy.

Clothing, posture, and gaze became tools of reclamation. In one surviving Savannah portrait from the 1890s, a Black couple stands before a painted garden scene, the woman holding a lace parasol. Their expression is serious, composed, unsmiling—a performance of respectability in a city still bristling with white control. Yet within the photograph’s staging lies defiance: they have taken possession of the frame.

Other forms of Black visual culture—church murals, fraternal banners, hand-painted shop signs—also flourished in Savannah’s neighborhoods. Many were ephemeral, lost to time, but they formed a vernacular aesthetic of pride and resilience. In places like Yamacraw and Carver Village, these traditions continued through the 20th century: muralists, hair salon sign-painters, carvers, church window designers.

None of this was marginal. It was Savannah, spoken in a second visual language.

Savannah’s Women Artists: Domestic Space as Studio

In 19th-century Savannah, creativity often bloomed behind closed shutters. The city’s women—restricted by social convention, domestic expectation, and limited access to formal training—nonetheless shaped its artistic identity in enduring ways. Their tools were watercolor and thread, miniature ivory plaques, painted china, and finely worked silk. Their studios were parlors and bedchambers. Far from ornamental, these works formed a parallel visual tradition—quiet, precise, and surprisingly radical in their assertion of self and sensibility.

Miniatures, samplers, and watercolors in 19th-century parlors

Throughout the antebellum period, the miniature portrait was a favorite medium among Savannah’s upper- and middle-class women. Painted in watercolor on ivory or vellum, these palm-sized likenesses were tokens of affection, courtship, mourning, or memory. While many were produced by male itinerant artists, a number of Savannah women became skilled miniature painters in their own right, often trained by tutors or copying from pattern books imported from England and France.

These women rarely signed their works. Yet within the city’s family collections and museum archives, one finds miniature portraits—delicate and luminous—that bear the mark of female hands. The eyes are often the focus: carefully rendered, expressive, almost too large for the face. Clothing and hair are simplified. The effect is intimate, bordering on devotional. These images were not made for public display; they were designed to be kept close—inside lockets, pinned to walls, hidden in drawers.

Watercolor painting was another widespread accomplishment among educated Savannah women. While rarely admitted into oil painting academies, women were encouraged to pursue “ladylike” art forms, and watercolor flourished as a semi-private medium. Landscapes of local marshes, garden scenes, and floral still-lifes filled scrapbooks and drawing portfolios across the city.

In some cases, these were refined enough to be exhibited. One such artist, Louisa Porter, was known for her botanical studies and contributed illustrations to scientific volumes. Her precise, almost scientific attention to form bridged the divide between amateur art and professional study—a common path for women artists across the South.

Textiles also played a major role. Samplers—embroidered panels combining alphabets, Biblical verses, and decorative borders—were among the first forms of visual expression taught to girls. These stitched compositions, made as early as age eight, were displayed proudly in parlors and passed through generations. Some were devotional; others contained family records or commemorated death. A few were overtly political, referencing national events in coded motifs.

These arts may seem quiet beside oil paintings and monuments, but their cultural weight was immense. They were visual proof of refinement, piety, and skill—and they formed the bedrock of Savannah’s interior aesthetic.

Gwendolyn B. Robinson and the gendered gaze

By the late 19th century, a few Savannah women began to push beyond domestic arts into more public realms. Among them was Gwendolyn B. Robinson, a painter and teacher whose name appears sporadically in exhibition catalogs and school records. Though little of her work survives, Robinson’s watercolors and oil portraits were displayed at local fairs and included in civic exhibitions alongside male artists. Her favored subjects—women in garden settings, children reading by lamplight, intimate interiors—reflected a feminine worldview that rejected grandiosity in favor of emotional immediacy.

Robinson’s correspondence, preserved in part by descendants, reveals her frustrations with institutional gatekeeping. In one letter, she writes: “I must paint my women as they appear to me—not as models, but as people who carry feeling in their hands.” Her emphasis on gesture, posture, and atmosphere placed her squarely within the aesthetics of the American tonal movement, though she remained unrecognized by its major practitioners.

Her gaze was not neutral—it was shaped by Savannah’s deeply gendered society, but it resisted caricature. She refused the sentimental tropes common in women’s art of the time: no angelic children, no dewy-eyed brides. Instead, she depicted working women, weary mothers, and contemplative figures in unguarded moments. Her technique—a mixture of loose brushwork and careful lighting—made these women glow not with innocence, but with presence.

Robinson’s limited success speaks to the constraints placed on women artists in Savannah even after the Civil War. Few institutions supported their development. The Telfair Academy, while progressive in preserving art, did not offer regular instruction for women until much later. Robinson, like many of her contemporaries, taught private students, exhibited locally, and painted in the margins of her domestic obligations.

Her legacy is subtle but visible. A Robinson portrait of a teacher hangs in the archives of a Savannah school; another, unsigned, is likely misattributed to a male peer. She stands as one of many women whose artistic contributions have yet to be fully recognized—not because they were minor, but because they were inconvenient to a male-centered canon.

Art clubs, salons, and the rise of feminine exhibition networks

The turn of the century saw a flowering of women-led art initiatives in Savannah. Inspired by national movements and aided by a rising class of educated women with leisure time, the city’s female artists began to form clubs, societies, and salon circles. These were more than social gatherings—they were crucibles of critique, mentorship, and exhibition.

One of the earliest was the Ladies’ Art Circle of Savannah, founded in the 1890s. It met monthly in rotating homes and sometimes hosted small exhibitions open to the public. The Circle focused on watercolor, embroidery, and still-life oil painting, but its members also collaborated with musical and literary societies, creating multimedia salons reminiscent of Paris and Boston. Within these domestic gatherings, women gained the confidence to exhibit more widely—and occasionally to sell their work.

These networks also connected Savannah women to larger Southern and national organizations, such as the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors and the Southern States Art League. Through these affiliations, a few managed to send work to regional biennials and even the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Art was not the only thing shared. These circles offered an alternate intellectual life. Women read essays on Ruskin and Whistler, debated the morality of nude painting, and studied Greek statuary through plaster casts. They treated aesthetics seriously, even if their city—and husbands—sometimes did not.

As Savannah modernized, so did the women’s art world. By the 1920s, photography, batik, and design entered the repertoire. Women experimented with cubism and abstraction, though more cautiously than in New York or Berlin. Still, their domestic studios—the converted sunrooms and garden sheds—remained their strongholds. In these intimate spaces, they shaped an artistic culture that was private, sustaining, and quietly revolutionary.

Preserving the Past: Historicism and the Visual Politics of Memory

By the mid-20th century, Savannah’s artistic energy had shifted decisively from the creation of new forms to the preservation of old ones. The city, long admired for its architectural elegance, became the stage for one of the earliest and most influential historic preservation movements in the United States. But preservation in Savannah was never simply about saving buildings—it was about saving an image, a version of the past rendered in brick, iron, and moss. This work of curation became, in itself, a dominant visual culture: a kind of civic artistry shaped by memory, selection, and omission.

Mid-20th-century preservation as artistic enterprise

The defining moment came in 1955, when a small group of women, horrified by the planned demolition of the 1820 Davenport House, formed the Historic Savannah Foundation. At a time when urban renewal was bulldozing historic neighborhoods across America, Savannah’s preservationists acted with speed and shrewdness, using private capital and political pressure to buy and save endangered properties.

From the outset, their mission was as much aesthetic as historical. Photographs from the period show board members standing proudly before newly saved buildings, flanked by flowering vines and freshly painted shutters. The rhetoric of the Foundation was clear: Savannah’s beauty was its identity, and beauty was not a luxury—it was a civic imperative.

This movement catalyzed a broader shift in how Savannah was seen and understood. Preservationists didn’t just restore buildings; they re-staged the city. They removed additions, chose specific historical periods for restoration (often antebellum), and emphasized a visual grammar of elegance: fluted columns, gas lamps, fanlights. These decisions were driven not only by historical fidelity, but by taste. They were acts of composition, not merely conservation.

Painters and photographers followed. The preservation boom gave rise to a new wave of visual documentation: street scenes in soft focus, architectural studies in chiaroscuro, plein air paintings of oak-draped squares. These works often reinforced the vision preservationists were promoting: a Savannah frozen in time, harmonious and untouched.

This was not, strictly speaking, myth-making. The buildings were real. The craftsmanship was genuine. But what was preserved—and what was allowed to fade—was shaped by cultural and political priorities. The past, like any artwork, was edited.

The Historic Savannah Foundation and aesthetic ideology

The Historic Savannah Foundation’s early success reshaped more than the streetscape—it reshaped the city’s cultural self-image. In pamphlets, newsletters, and public talks, the Foundation emphasized Savannah not just as a historic city, but as a curated masterpiece. This framing influenced how artists worked, how tourists imagined the city, and how residents defined their heritage.

Behind this was a powerful ideology: that beauty conferred legitimacy. This belief led to careful vetting of what kinds of buildings qualified for preservation, often privileging the high styles of Federal, Greek Revival, and Victorian design over vernacular structures. Entire neighborhoods were effectively excluded from preservation narratives, particularly those associated with working-class Black communities, whose architectural contributions were deemed “less significant” under prevailing criteria.

At the same time, the Foundation’s efforts succeeded in stabilizing the historic core of Savannah and preventing the kind of architectural annihilation seen in cities like Atlanta or Jacksonville. The result was a living museum, dense with aesthetic coherence—one that attracted artists, historians, filmmakers, and preservationists from around the world.

But coherence came at a cost. The city’s new visual identity leaned heavily into antebellum romanticism. Tourist materials from the 1960s and ’70s featured horse-drawn carriages, hoop skirts, and porticoed mansions. This visual fantasy often sidestepped Savannah’s more complicated histories—of slavery, war, labor, and immigration—in favor of a Southern charm that was both marketable and sanitized.

Artists working within this framework faced a dilemma. Should they participate in the beautification of memory, or challenge it? Some did both, painting historic homes in exquisite detail while quietly including signs of neglect, resistance, or modern intrusion: a satellite dish on a plastered wall, a cracked window reflecting neon light.

For others, the preservationist aesthetic became a constraint. They turned away from nostalgic forms and sought out new subjects—warehouses, riversides, marginalized neighborhoods—not yet sanctified by curatorial consensus.

Museums as mediators of beauty and nostalgia

No institution better embodied Savannah’s preservationist artistic ethos than the Telfair Museums, particularly the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences. Housed in an 1819 Regency-style mansion designed by William Jay, the Telfair was the South’s first public art museum and became a centerpiece of the city’s aesthetic self-image.

During the 20th century, the Telfair’s curators worked to align the museum’s holdings with the city’s broader architectural narrative. Exhibitions emphasized American and European academic painting, neoclassical sculpture, and decorative arts—forms that mirrored the elegance of the surrounding neighborhood. Docents led tours that focused as much on the building’s design as on the art it contained. The museum itself was an exhibit.

But even here, the limits of nostalgia became apparent. Contemporary artists began to question the frame. In the 1990s, the Telfair expanded its mission to include modern and contemporary works, culminating in the opening of the Jepson Center for the Arts in 2006—a glass-and-steel structure by Moshe Safdie that broke decisively with the city’s historicist aesthetic.

The Jepson’s arrival was controversial. Critics called it jarring, inappropriate, even “soulless.” But for others, it marked Savannah’s return to living culture. Inside, exhibitions began to feature artists who challenged the city’s myths: photographers capturing gentrification in real time, painters reimagining the South through surrealism and abstraction, installation artists using the city’s streets and memories as raw material.

Even the Telfair’s original building began to house more challenging work, reframing its spaces not just as showcases of preserved taste, but as stages for dialogue. Portraits of slaveholding families now hung beside interpretive materials that complicated their legacy. Decorative arts galleries were accompanied by panels discussing the labor behind their creation. The past had not been abandoned—but it had been contextualized.

Savannah, through the very act of preserving its image, had made visual history an artistic medium in itself. To walk its streets was to enter a curated scene. The challenge for contemporary artists—and for its residents—was to decide whether to continue painting within that scene, or to begin painting over it.

SCAD and the Birth of the New Bohemia

In 1978, Savannah underwent a transformation that had nothing to do with port traffic, politics, or preservation—but everything to do with vision. That year, a small, underfunded arts college opened its doors in a repurposed armory building on Bull Street. The Savannah College of Art and Design, now known by its global acronym SCAD, would go on to reshape the city’s artistic identity from the inside out. What began as a hopeful experiment in creative education soon catalyzed an urban renaissance, injecting youth, risk, and international ambition into a city once content to rest on its laurels.

The Savannah College of Art and Design as cultural engine

SCAD’s founding story is modest: a group of educators and entrepreneurs, led by Paula Wallace, purchased the former Savannah Volunteer Guards Armory with the idea of building a small art school. But the idea was radical for its time and place. Savannah in the late 1970s was beautiful but stagnant—a city rich in buildings but thin in vision. Tourism was minor, galleries were few, and the local art scene was cautious, hemmed in by Southern gentility and economic inertia.

SCAD’s arrival disrupted that equation. Within five years, it had begun to absorb vacant buildings—hotels, warehouses, theaters—and repurpose them into classrooms, studios, and dorms. This architectural reclamation was not merely functional. It was aesthetic. SCAD’s founders understood that the city’s historic core was not an obstacle to modernity, but its platform. Where other institutions might have demanded sleek new campuses, SCAD embraced the decayed grandeur of old Savannah, treating every restoration as an act of creative archaeology.

The effect was immediate. Students from across the country—and soon the world—began arriving in Savannah, bringing with them new styles, new media, and new demands. Their presence altered the city’s tempo. Cafés, bookstores, and print shops multiplied. Formerly derelict corners of the Historic District turned into studio spaces and design firms. A new creative economy took root, one built not on nostalgia but on experimentation.

SCAD functioned not only as a school, but as a cultural engine. It launched galleries, hosted film festivals, opened museums, and began collecting contemporary art. It commissioned public works, sponsored installations, and gave scholarships to local students who might never have considered art a viable future. The institution did not simply teach creativity—it broadcast it.

Adaptive reuse: turning decay into design

One of SCAD’s most enduring contributions to Savannah’s visual culture is its philosophy of adaptive reuse. Rather than demolish or mimic the past, the college’s architects, designers, and preservationists set about transforming old buildings into vibrant, modern environments while preserving their historical integrity. This approach became an aesthetic in itself—equal parts restoration, intervention, and provocation.

Consider the transformation of Poetter Hall, the original armory, into a vibrant centerpiece of SCAD’s campus. Its brick exterior remained, but inside, studio lights, digital labs, and student work reanimated the structure. The former Central of Georgia Railroad complex became the SCAD Museum of Art—a contemporary exhibition space housed in 19th-century walls. Here, minimalism and ruin cohabited.

The result was not seamless. It was textured. Exposed beams, scarred floors, and preserved signage spoke not of glossy reinvention, but of layered continuity. This aesthetic—sometimes called “high-bohemia”—found imitators among local businesses and independent artists. Boutique hotels, loft apartments, and performance venues adopted the look: part salvage yard, part gallery, always intentional.

This style fed a broader visual economy. Photographers began using SCAD buildings as backdrops. Fashion designers shot lookbooks in decrepit stairwells and sunlit studios. Graphic designers adopted the weathered typography of old signage. The city itself, once static, became a palimpsest—an active surface on which past and future rubbed shoulders.

And it was students who brought it to life. With them came piercings, protest art, installation work, queer aesthetics, digital experimentation. They arrived with sketchbooks and laptops, spray cans and DSLR cameras. They tagged alleyways, repainted bicycles, installed pop-up exhibitions in storefront windows. What began in lecture halls spilled into the streets. Savannah, for the first time in a century, felt young.

Youth, experimentation, and internationalization of local art

SCAD’s global recruitment strategy transformed the city into a cultural crossroads. Korean industrial designers, Nigerian fashion students, Icelandic photographers, and Appalachian animators shared studios and sidewalks. The resulting collisions of culture turned Savannah into something it had never quite been: cosmopolitan.

This had aesthetic consequences. Local galleries began to show work that was less regionalist and more transnational. Fiber artists from New Delhi shared space with Southern folk painters. Street photographers documented the fusion of past and present: a Vietnamese student wearing traditional silk on a cobbled square; a German sculptor building a post-minimalist piece in a former Baptist church.

Students led much of this charge. Their thesis shows, pop-up galleries, and film screenings redefined what Savannah art looked like. No longer confined to genteel watercolors and architectural studies, the city’s visual culture now included:

- Large-scale performance art in derelict lots, addressing race, gender, and space.

- Immersive digital installations, staged in repurposed warehouses with motion sensors and projection mapping.

- Experimental fashion shows, where garments crafted from recycled materials took inspiration from antebellum silhouettes and Afrofuturist motifs.

The old Savannah and the new did not always sit comfortably together. Some locals bristled at the aesthetic audacity of SCAD’s projects. Critics accused the institution of gentrifying historic neighborhoods, of commodifying local culture, of prioritizing spectacle over substance. These critiques were not unfounded. As SCAD grew, rents rose. Longtime residents were displaced. The very vitality the school injected into the city threatened to erode its social equilibrium.

But even detractors admitted that the city had changed. It had become a destination not only for tourists, but for talent. Young artists came to Savannah not to look back, but to test what art could do in a place so saturated with memory.

In many ways, SCAD did not simply transform Savannah. It challenged it. The city of squares and cemeteries had to reckon with graffiti and glitch art, with zines and augmented reality. And far from overwhelming its history, this creative influx made the past newly legible—refracted through modern eyes, reanimated by urgent questions.

Public Walls and Private Meanings: Street Art, Graffiti, and Urban Murals

In a city that has long curated its public image with neoclassical symmetry and preservationist discipline, the emergence of graffiti, murals, and unsanctioned street art might seem disruptive. And it is. But it is also a kind of reclamation—a counter-aesthetic in which Savannah’s walls, once reserved for ivy and plaque, become canvases for frustration, humor, resistance, and celebration. What began as marginal mark-making in back alleys and underpasses now plays a central role in the city’s visual identity, albeit one still fraught with conflict and ambiguity.

Murals as social commentary and spatial reclamation

Savannah’s first large-scale murals appeared not on museum walls or curated facades, but in informal spaces: the sides of convenience stores, the backs of auto garages, the boarded-up windows of abandoned homes. In the 1990s and early 2000s, these paintings were often the work of local artists working outside traditional channels, many with backgrounds in graffiti or sign painting. The images varied—some were purely decorative, others overtly political—but they all shared a sense of urgency. The wall was not a passive surface; it was a battleground.

One of the earliest and most influential figures in this movement was Panhandle Slim, a folk artist whose bold portraits and stenciled slogans began appearing on wood panels, fences, and vacant buildings throughout the city. His subjects ranged from Nina Simone to John Lewis to obscure civil rights activists, each depicted in flat planes of color and accompanied by handwritten aphorisms. The work was both homage and provocation: public, legible, and emotionally direct. Slim’s portraits asserted presence where absence had reigned.

Other muralists took a different approach. The Starland District—a once-neglected stretch of Savannah south of Forsyth Park—became a testing ground for large-scale, site-specific works. Artists used entire facades to create immersive compositions: tropical dreamscapes, abstract color fields, surreal allegories of Southern life. Some were commissioned; others simply appeared. The city’s permissive code enforcement—sometimes lax, sometimes uneven—allowed a certain ambiguity to flourish. Was it vandalism, or beautification? The answer depended on the address.

A key example is the “Faces of Savannah” mural, a sprawling composition painted in 2015 on a warehouse wall near 41st Street. Featuring stylized portraits of local residents, from cooks and musicians to elders and children, the mural was part community project, part civic intervention. It invited passersby to recognize themselves in the cityscape—not as historical abstractions, but as living participants. Within weeks, tags appeared beside it. Some were insults; others were tributes. The mural absorbed them all.

Murals like these do more than decorate—they contest space. In a city where so much of the visual language is inherited, permanent, and orderly, street art injects the temporary, the personal, the improvised. It asks who gets to speak on the walls of Savannah, and in what tone.

The city as gallery: River Street to Starland

Nowhere are Savannah’s visual contradictions more vivid than along River Street. Here, 18th-century cotton warehouses have been converted into boutiques, bars, and galleries, their exteriors polished for tourist consumption. Yet just a few blocks inland, on crumbling walls and utility boxes, the city’s unofficial gallery emerges.

These smaller interventions—stickers, stencils, paste-ups, and tags—form a visual ecosystem parallel to the sanctioned art world. Some carry political messages: anti-racist slogans, environmental warnings, demands for housing justice. Others are cryptic symbols, recurring signatures, or playful non sequiturs. A stencil of a pigeon in a gas mask appeared on 39th Street in 2019 and was replicated across Midtown for months, its meaning debated in online forums. Was it anti-tourism? Anti-gentrification? A joke? The ambiguity was the point.

SCAD students and alumni have played a role in blurring the line between street art and institutional work. Some graduates who trained in printmaking or illustration have turned to wheatpaste posters and mural commissions. Others collaborate with local businesses or nonprofits to create public works that retain the spontaneity of graffiti while operating under permits. The city itself has begun to adapt. In 2020, the City of Savannah launched a pilot mural ordinance allowing artists to apply for approval on public walls, though critics argue the process remains restrictive and opaque.

This tension is constant. One month, a mural goes up with city support; the next, a tag appears over it and is swiftly removed. At stake is not just control of space, but control of narrative. In a city whose identity is built on visual order, every unsanctioned mark is a rupture—but also a revelation.

Savannah’s walls now contain multitudes:

- Historic advertisements for tobacco and patent medicines, faded but legible.

- Layered graffiti built up over years, often semi-legible names or cartoon characters.

- Curated murals painted as part of festivals, with sponsors and signage.

This layering creates a cityscape of competing visual languages. The eye jumps from curated beauty to contested space, from polished surface to spontaneous scrawl. And in this juxtaposition, the city becomes legible not as a museum, but as an argument.

Conflicts over visibility, commerce, and control

With the rise of urban murals has come the inevitable backlash. Some longtime residents see the proliferation of street art as a symptom of gentrification—an aesthetic that signals cultural change but often precedes displacement. Others view it as desecration: a defacing of sacred or historic ground. In a city where nearly every building is landmarked, the act of painting a wall becomes a moral act as much as a visual one.

There have been flashpoints. In 2016, a mural of a skeletal figure titled “The Watcher,” painted on a private building in the Victorian District, drew complaints from neighborhood associations. Though painted with permission, the mural was deemed “unsettling” and “inappropriate for the neighborhood character.” It was painted over within weeks, prompting protests and counter-protests about censorship and cultural policing.

These disputes reveal the stakes. Public art in Savannah is not just decoration—it is a claim. A mural can reclaim a neglected space, but it can also be read as intrusion. A tag can be art or blight, depending on who sees it. The city, ever curated, resists ambiguity. But ambiguity thrives on its walls.

Artists, aware of this, increasingly build subversion into their practice. Some works are designed to weather quickly, to fade or be removed. Others are left unsigned, anonymous, collective. The goal is not always permanence, but impact. A mural need not last to matter—it need only be seen.

At the same time, the economics of street art have shifted. Festivals like the Savannah Urban Arts Expo, launched in the early 2010s, began to attract corporate sponsorship. Murals once born of rebellion were now backdrops for selfies and tourism marketing. Some artists embraced this shift, using visibility to fund more radical work elsewhere. Others withdrew, refusing to participate in what they saw as co-optation.

The paradox is clear. In a city famous for its preserved past, street art has become the most visible sign of its present. It is volatile, inconsistent, often beautiful, often crude. It is democratic and dangerous, ephemeral and monumental. And as long as Savannah’s walls remain contested, its art will remain alive.

Shadow and Fire: Ghost Tours, Dark Tourism, and the Aesthetics of the Macabre

No city in the American South has so thoroughly intertwined its visual culture with death as Savannah. What began as quiet mourning in cemeteries and private parlors has, over the past three decades, evolved into a full-blown public theater of the macabre. Ghost tours, haunted inns, and “dark history” walking trails now shape how millions experience the city each year. But this isn’t just kitsch or commerce—it is a sustained aesthetic mode, a carefully cultivated style in which history is filtered through shadow, firelight, and suggestion. And like all visual styles, it reflects deeper cultural anxieties.

How Savannah’s supernatural branding shaped its visual art

The modern transformation began in the 1990s, with the publication of John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. The book, and later the film, established Savannah not simply as a charming historic city, but as a stage set for sin, secrecy, and spectral intrigue. Its success gave rise to an entire industry: ghost tours, paranormal investigations, haunted pub crawls. More than fifty ghost tour companies now operate in the city, each offering its own curated version of Savannah’s past.

These tours rely heavily on visual cues. Carriages creak through moonlit squares. Gas lanterns flicker beside gravestones. Guides dress in period costume, carry antique lanterns, and speak in theatrical cadences. Houses are not simply described as haunted—they are framed like stage sets, lit from beneath, veiled by curtains, reflected in puddles. The entire experience is an orchestrated play of light, texture, and suggestion.

Local artists responded to this shift with an outpouring of spectral imagery. Galleries along River Street and in the Starland District began selling prints and paintings that blurred the line between gothic kitsch and sincere mysticism: faceless figures under oak canopies, anthropomorphic ravens, moss-draped windows glowing from within. Photographers staged long-exposure night shots of Bonaventure Cemetery, capturing the grainy hush of candlelit vigils and imagined apparitions.

The aesthetic bled into commercial design. Boutique hotels adopted dimmer lighting and Victorian décor. Menus were printed in old typefaces. Tattoo parlors advertised ouija board themes. Even corporate branding began to borrow the visual language of haunting. A local rum distillery adopted the ghost of a pirate as its mascot. The effect was subtle, but total: Savannah was no longer merely beautiful—it was haunted.

This wasn’t just a marketing choice. It was an art direction. The city rebranded itself as a living gothic novel, and in doing so, artists and designers across media found a ready-made atmosphere to inhabit.

Theatricality, myth, and morbid kitsch

Savannah’s dark tourism scene is nothing if not theatrical. Nighttime trolley tours blast fog from hidden vents. Tour guides adopt invented personas—widowed seamstresses, war-time undertakers, voodoo priestesses—and deliver their stories with a blend of menace and wry humor. The entire experience is calibrated not for historical accuracy, but for affect: a shiver, a flicker, a laugh in the dark.

This theatricality has begun to influence visual artists, many of whom now treat the ghost tour as an art form unto itself. Performance artists stage one-night-only “haunted walks” that double as installations, incorporating projection mapping, recorded whispers, and sculpture. A 2021 piece, “Apparitions on Abercorn,” used shadow puppets and found audio to narrate a fictional haunting in an empty storefront. The audience followed the action from outside, watching through fogged glass and alley entrances.

Meanwhile, the fine line between gothic and kitsch continues to animate visual debates. Critics argue that the proliferation of ghost-themed souvenirs—plastic skulls, glow-in-the-dark postcards, rubber rats—has turned the city’s traumatic history into theme-park fodder. Indeed, stories of slavery, epidemic, and murder are often served with a wink and a cocktail, their horror softened into camp.

But some artists have pushed back. They mine the same territory—ghosts, graves, Southern death—but with an eye toward tension rather than comfort. Photographer Daniel E. Smith’s series What Remains captured empty interiors and ruined staircases, bathed in twilight, with no ghosts but a heavy sense of presence. His images draw not from folklore, but from atmosphere—what’s left after life departs.

Sculptor Renata Cross’s “Shrine to the Unnamed,” installed temporarily in an abandoned courthouse hallway, used reclaimed wood and scorched fabric to invoke the memory of those never buried in Savannah’s official cemeteries. Her work confronted the selective nature of the city’s haunted narrative, asking: whose ghosts are we willing to see?

These artists take the aesthetics of dark tourism seriously—not to glorify, but to interrogate. In their hands, Savannah’s shadows become not performance, but critique.

Darkness as Southern identity and artistic brand

The idea of the South as a place of darkness—moral, historical, atmospheric—has long animated American art and literature. From Faulkner’s decaying mansions to Flannery O’Connor’s peacocks and prophets, the Southern Gothic is a genre rooted not just in mood, but in memory: a reckoning with past violence through distortion, exaggeration, and grotesque beauty.

Savannah has embraced this tradition more visibly than any other Southern city. Its tourism industry, preservation ethos, and artistic scene all traffic in the language of decay. Even contemporary artists who reject nostalgic painting or Confederate iconography often return, visually, to the forms of the uncanny: fog, masks, shadowed rooms, palimpsests of brick and blood.

Three recurring motifs dominate:

- The empty house, usually antebellum, rendered as both refuge and trap.

- The twisted tree, symbolic of natural resilience and contorted history.

- The specter, sometimes literal, sometimes implied—a figure at the edge of recognition.

These motifs appear across genres: in gallery canvases, graphic novels, short films, and street murals. The ghost, for many Savannah artists, is less a supernatural being than a visual metaphor. It represents memory unacknowledged, presence denied, inheritance avoided.

As a result, Savannah’s macabre aesthetic has matured. It is no longer just tourist fare—it is a legitimate mode of regional expression. Artists use the language of haunting to talk about race, gender, violence, grief. They invoke the dead not to entertain, but to bear witness.

And yet the tension remains. For every artist plumbing the depth of the gothic, there is a souvenir shop selling plush ghosts and cocktail glasses shaped like coffins. Savannah is both things: a serious city of artistic reckoning, and a charming set for tourists playing at fear. Its art lives in that contradiction.

The shadow sells. But it also speaks.

Contemporary Currents: Black Futures, Queer Spaces, and Ecological Art

Savannah has never been a static city. Beneath the wrought-iron balconies and under the shade of its ancient oaks, new artistic movements have taken hold—movements that speak not to nostalgia or restoration, but to possibility. Over the past two decades, a generation of artists has emerged committed to exploring identity, environment, and futurity. Their work is not decorative. It is declarative. Drawing from Black aesthetics, queer theory, ecological urgency, and post-industrial space, these creators are redefining what it means to make art in Savannah now.

Art as activism in 21st-century Savannah

In Savannah, art has become a site of political engagement—not through polemics, but through presence. Murals, performance pieces, installation work, and ephemeral interventions have all served as vehicles for social commentary and community solidarity. In the wake of the George Floyd protests in 2020, a wave of public art swept through the city, particularly in the Starland and Carver Heights neighborhoods. Street corners once used for passive foot traffic became sites of urgent visual speech.

One prominent work was a temporary mural titled Say Their Names, organized by a coalition of SCAD alumni, local high school students, and church artists. Painted directly onto the street at the intersection of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Jones Street, the piece featured the names of Black Americans killed by police, interwoven with symbols drawn from African textiles and coastal Gullah patterns. Though weather-worn and eventually painted over by city crews, the mural left a deep impression: Savannah’s past might be fixed, but its present could speak loudly.

Other artists, such as multimedia practitioner Raven Matthews, have blended digital projection, oral history, and textile art to create installations that explore systemic racism through family memory. Matthews’ 2021 exhibition Bloodroot at Sulfur Studios included a suspended map of Savannah stitched from hair, lace, and police tape. Visitors passed beneath it, reading testimonies projected onto the floor—an immersive invocation of Black inheritance in spaces that once erased it.

These works exist in tension with the city’s traditional aesthetic. Where historic preservation once softened violence into charm, these contemporary artists lay it bare—while still honoring form, ritual, and beauty. Their materials may be unconventional, but their ambition is nothing less than architectural: to rebuild meaning in public space.

The new generation of Black and queer creators redefining Southern aesthetics

Perhaps no demographic has transformed Savannah’s contemporary art scene more profoundly than the network of young Black and queer artists who have chosen to make the city their base—not despite its conservatism, but because of the creative challenge it offers. These artists confront the city’s haunted legacy directly, using it not just as backdrop but as antagonist, foil, and foilable.