Long before canvas and oil ever arrived on Western Australian shores, the region that would become Perth was alive with visual knowledge systems inscribed directly into the land. For the Whadjuk Noongar people—the traditional custodians of the southwest corner of Australia—art was not a category separate from daily life, ritual, or history. It was embedded in place, practice, and speech, a visual language spoken across ochre-marked rocks, engraved surfaces, and the ceremonial adornment of bodies. The absence of easels or galleries in no way diminishes the sophistication or continuity of this visual tradition, which shaped the cultural landscape for tens of thousands of years before European arrival.

Rock, Earth, and Line: The Foundations of Noongar Visual Culture

The terrain surrounding what is now Perth is marked by thousands of cultural sites, many of which contain carved, painted, or otherwise modified rock formations. Among these are petroglyphs—images pecked or incised into stone—and ochre paintings made from naturally sourced pigments. The sites at Yellagonga Regional Park, Walyunga National Park, and the wider Swan Coastal Plain hold examples of such markings, many of which are deeply tied to ancestral stories known as Dreamings—though the Noongar word is Nyitting, which refers more precisely to the “cold time” or beginning of time.

What may appear abstract or minimal to a European-trained eye is often densely referential within Noongar cosmology. A series of concentric circles might represent a waterhole, a meeting place, or the site of a historical event, depending on context and interpretation. Lines can trace journeys made by ancestral beings or indicate the direction of ceremonial movement. Far from decoration, these forms are mnemonic devices—maps of memory, territory, and law.

The visual culture of the Noongar was inherently local, but not static. Patterns shifted with seasonal movements, and with them, the oral stories that accompanied visual symbols. The act of painting or carving was often ceremonial, performed in relation to song, dance, or initiation. The earth was not a passive surface to be marked, but an active participant in a continuing dialogue between the past and present.

Three notable features distinguish this tradition from imported European art systems:

- Integration with place: Art was site-specific, with forms and meanings deeply tied to the exact topography where they appeared.

- Multimodal practice: Visual marks were never isolated from language, song, and movement.

- Transmission over permanence: Durability was less important than the role of art in cultural transmission; renewal, rather than preservation, was often the priority.

Broken Lines: Early Disruptions and Cultural Loss

The arrival of British settlers in 1829 marked an abrupt rupture in the visual life of the Whadjuk Noongar. The Swan River Colony brought new ways of claiming and describing land—surveyors’ grids, property lines, and maps that ignored or erased existing cultural markings. Sites of spiritual and historical significance were quarried, developed, or simply dismissed. The colonial preference for paper documentation over oral and ritual knowledge contributed to the rapid marginalization of local traditions.

A particularly stark example of this disjunction occurred in the area now known as Kings Park. Once a ceremonial site called Karrgatup, it was renamed and landscaped in the image of an English parkland. The visual erasure extended into everyday life: markings on trees, ground ochre sites, and ceremonial grounds were seen as curiosities at best, vandalism at worst.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, what little Noongar art did survive was often extracted and recontextualized as anthropological specimen. Museum collections in Perth, Adelaide, and overseas absorbed carved shields, boomerangs, and painted artifacts without consideration of their spiritual or ceremonial significance. This collecting impulse often stripped objects of their context, freezing them into silent displays. What was once part of a living visual system became a category of “ethnographic art.”

There were exceptions. Some colonial observers, such as Daisy Bates and later Ronald and Catherine Berndt, recorded Noongar practices with greater attentiveness, though still through the lens of early anthropology. More significantly, many families quietly continued traditions in rural and fringe-dwelling communities, passing knowledge along in forms adapted for survival.

Lines Rekindled: Survival Through Practice, Not Preservation

Despite these losses, the visual culture of the Whadjuk Noongar did not vanish—it shifted, adapted, and in some cases, went underground. Body painting for corroborees continued in private settings; markings were etched discreetly into trees or tools; ochre was still sourced for ceremonial use. Importantly, the role of art as a means of teaching law, recounting history, and connecting people to land remained.

One understated but powerful medium for continuity was the carved message stick, often used to communicate across groups. These were not simply functional objects but visual artifacts rich in symbolic meaning. Their use into the 20th century demonstrates the endurance of visual literacy even in conditions of dispossession.

In the late 20th century, as legal and cultural recognition of Aboriginal traditions grew—albeit unevenly—Noongar artists began to reclaim and re-present these traditions in new ways. Works by elder artists such as Shane Pickett (1957–2010) drew from ancestral imagery while using acrylic and canvas, participating in both cultural renewal and the broader contemporary art world.

Pickett’s paintings, with their rhythmic, gestural fields, were not abstract in the Western sense. They evoked the movement of wind over country, the shifting presence of ancestral beings, and the quiet authority of place. He once described his art as a form of “cultural maintenance”—a continuation rather than a re-creation.

In more recent years, younger artists like Ilona McGuire have taken this inheritance into new domains, including projection art and public installations. Their work reasserts Noongar presence in the urban space of Perth, which has often denied or occluded its pre-colonial past. Rather than nostalgia, these visual forms are acts of sovereignty and continuity.

A significant piece in this vein is the collaborative project Ngaangk (meaning “mother” or “sun”), projected onto the façade of the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2022. Rather than simply displaying motifs, it wove together language, movement, and digital animation in a mode strikingly consistent with ancestral principles—multimodal, site-responsive, and alive with meaning.

The long history of Noongar visual culture in Perth is not one of simple survival against the odds. It is a story of adaptation, interruption, and reassertion—a visual tradition that continues to operate not as a historical curiosity, but as an evolving system of knowledge rooted in a specific place. It remains the first art history of Perth, and one whose influence continues to surface in unexpected and powerful ways.

Drawing the Colony: Early European Art and the Image of Settlement

The first artistic impressions of Perth did not begin with inspiration—they began with inventory. When British settlers arrived on the banks of the Swan River in 1829 to establish a new colony, their early visual output was driven less by creative ambition than by necessity: the need to chart, measure, possess, and report. Artistic labor, in these formative years, functioned primarily as a form of imperial recordkeeping, tasked with transforming the unfamiliar terrain into something legible to those back in London. Yet in this utilitarian practice, one begins to see the aesthetic frameworks that would shape European understandings of Western Australia for decades to come.

Surveyors, Soldiers, and Sketchbooks

Among the first visual chroniclers of the Swan River Colony were military men and government officials, not formally trained artists. Captain James Stirling, the colony’s first governor, brought with him not just officers and administrators but also draftsmen tasked with producing maps, coastal charts, and survey drawings. These early works often blended technical precision with an unacknowledged visual bias: the tendency to frame the land as open, unpeopled, and ripe for cultivation.

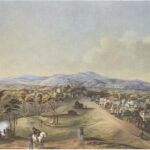

Figures such as Frederick Garling and Augustus Earle—both itinerant artists working across colonial Australia—produced sketches and watercolors that depicted the Swan River with an eye toward potential investors. Their compositions often resembled pastoral landscapes, showing cleared plots, modest buildings, and docile Aboriginal figures placed decoratively in the margins. These scenes weren’t merely descriptive; they were promotional. Sent back to Britain, they served to entice settlers, assert the colony’s viability, and smooth over the realities of conflict and failure.

A typical example is Garling’s View of the Swan River (c.1830), which presents a serene waterway flanked by trees and anchored by a small structure. The foreground features a few Aboriginal figures in repose, seemingly untroubled by the presence of European settlers. The composition is orderly, quiet, and inviting—a direct contrast to the rugged and often desperate conditions early colonists actually faced. This visual strategy was no accident. It was part of a broader imperial tendency to aestheticize new territories as both empty and harmonious, as if the land itself were anticipating European improvement.

Making Sense of the Land: Aesthetics of Control

Behind the scenes of these idyllic sketches was a deeper project: the imposition of an imported visual logic onto a landscape that defied easy classification. The Swan Coastal Plain, with its unusual light, sandy soils, and disorienting flora, did not readily conform to the familiar categories of European representation. Trees such as the balga (grass tree) and marri looked grotesque or alien when rendered in ink. Hills were flat, shadows behaved strangely, and the vastness of the bush resisted the depth cues of classical perspective.

Faced with this visual strangeness, colonial artists often fell back on formula. They restructured scenes to resemble the English countryside, downplayed scale, and omitted the more unruly aspects of the bush. The result was a strange hybrid: a landscape that looked “natural” only because it had been subtly refashioned to suit European eyes.

Three recurring techniques helped achieve this:

- Foreground framing: Trees or rocks were placed at the edges of compositions to create a sense of pictorial enclosure.

- Vanishing lines: Roads, rivers, or cleared paths were used to guide the viewer’s eye into the scene, imposing depth and order.

- Miniaturization: Distant structures or figures were scaled to make the land seem more settled and comprehensible.

Even seemingly scientific drawings were not immune to this aesthetic impulse. Botanical illustrations by artists like Ferdinand Bauer, who had worked on earlier expeditions, filtered native plants through conventions of European botanical art. While accurate in detail, the presentation style—isolated specimens on clean white backgrounds—divorced the plants from their ecological context, turning them into collectibles rather than living elements of a complex system.

In this way, early art in Perth was not just a record of occupation but a tool of it. The act of sketching a coastline or painting a homestead was part of a broader cultural effort to transform the unknown into the knowable, the resistant into the manageable.

The Romantic Veil: Sentiment and Settlement

As the colony stabilized and settlers began to establish farms and towns inland, a more sentimental mode of landscape painting emerged. By the mid-to-late 19th century, artists such as George Pitt Morison and George Temple-Poole—both of whom were also involved in architectural and civic projects—began to depict the region with a tone of romantic nostalgia. The bush was no longer merely a barrier to progress; it became a site of poetic reflection, a backdrop for the moral drama of colonization.

Morison’s The Foundation of Perth, 1829 (1929), though painted a century after the event, exemplifies this retrospective vision. Commissioned to commemorate the colony’s centenary, the painting shows a tableau of well-dressed settlers gathering on the banks of the Swan River, poised in orderly celebration. The Aboriginal presence is minimal and peripheral. The scene is composed like a Renaissance history painting—balanced, idealized, and full of symbolic gestures. It was less a documentary image than a foundational myth, a visual assertion of British orderliness and moral right.

This tendency to mythologize through art paralleled similar movements in other parts of Australia, but Perth’s relative isolation gave its imagery a particular cast. Unlike Sydney or Melbourne, where population growth and industrialization had begun to crowd the landscape, Perth’s artists could still depict the bush as open and unspoiled, even as it was being systematically transformed. This created a peculiar visual contradiction: the more the land was settled, the more artists depicted it as pristine.

One of the more surprising elements of this period is how infrequently conflict appeared in visual representations. Although the early years of the Swan River Colony involved violent clashes with Noongar groups, dispossession, and resistance, these events were largely absent from artistic output. When Aboriginal people appeared in paintings or illustrations, they were often shown as passive, noble, or picturesque—never as political actors. This erasure was not accidental. It reflected the prevailing desire to smooth over the rough edges of colonization and to present Western Australia as a peaceful frontier.

At the same time, a few works did hint at unease. Some sketches depict burned homesteads, broken fences, or rugged terrains too harsh to farm. These images—though rare—suggest a more ambivalent reality beneath the official optimism. In private diaries and correspondence, settlers often expressed fears, frustrations, and doubts that never made it into public-facing art. The act of drawing, in this context, became a form of self-reassurance.

Art in early colonial Perth was thus a double exercise: an attempt to capture the land and an attempt to believe in it. What began as a form of documentation quickly evolved into a means of cultural projection. The landscapes they painted were not simply what they saw, but what they needed to see.

The Painted Frontier: 19th-Century Landscape Art in the West

By the second half of the 19th century, the visual identity of Perth had begun to settle into recognisable patterns. The colony was no longer an improvised outpost but a growing civic entity with ambitions of refinement and permanence. The land, however, remained unpredictable. For artists working in and around Perth during this period, the challenge was no longer how to map the land, but how to make it emotionally and culturally legible—how to turn it into a view worth gazing at, collecting, or hanging in the drawing rooms of the new colonial elite. This meant not only painting what was there, but also, increasingly, painting what was imagined.

Pastoral Dreams and Decorative Landscapes

Unlike the volatile coastlines or tempestuous mountain scenes favored by European Romantic painters, the landscapes of Western Australia offered a more subtle palette. Here, drama came not from elevation or storm but from scale, stillness, and light. For colonial artists, the temptation was to domesticate this visual language—to soften the bush into scenery.

One of the more influential modes of the time was the pastoral landscape: a scene of productive land lightly touched by human presence. In these works, sheep dot the mid-ground, smoke rises from a chimney, and a meandering path leads the viewer into a settled horizon. These were not documentary images but visual reassurances, affirming the triumph of order over wilderness.

James W. R. Linton, a painter, teacher, and patriarch of a prominent artistic family in Western Australia, worked in this idiom with a studied grace. Though born in England, he spent most of his life in Perth and helped shape the local art scene well into the 20th century. His landscapes of the Swan Valley and Darling Ranges offered an English-inflected vision of the Australian environment—orderly, lyrical, and distinctly comfortable. His work, though technically fine, rarely veered into risk. It represented a kind of aesthetic settlement: the bush tamed not only by axe and plough, but also by brush and frame.

At the same time, decorative and applied arts flourished among Perth’s educated elite, many of whom saw painting as an accomplishment rather than a profession. Women, in particular, took up watercolour as a respectable pastime. Their sketchbooks often included wildflowers, coastal scenes, and idealized homesteads—rendered with care but also with the unspoken codes of respectability that governed colonial domestic life. The lines between personal, botanical, and artistic attention often blurred.

Three recurring motifs dominate these works:

- The bush as garden: Native flora arranged like English bouquets or borders.

- The homestead as center: Houses depicted from slightly elevated vantage points, granting them visual primacy.

- Light as benevolence: Golden afternoon tones smoothed over the landscape, avoiding the harsher vertical sun that actually dominated the region.

Wilderness by Imagination: The Distance Between Brush and Soil

Despite their surface realism, most 19th-century landscape paintings in Western Australia were strikingly removed from actual working life. The physical conditions of clearing land, tending sheep, or surviving drought rarely made it into the frame. Labour was invisible, and hardship implied only through picturesque ruin—an abandoned hut here, a broken fence there.

This visual filtering was not simply a failure of realism. It reflected deeper tensions within settler identity. The bush was both source and threat: it gave life but also overwhelmed it. As such, it had to be interpreted, not merely recorded. Artists turned to aesthetic conventions—borrowed largely from Europe—to domesticate what they could not control.

There is a telling contrast between painted and printed imagery. While paintings leaned toward the romantic and harmonious, printed illustrations—especially those produced for travel guides or journals—sometimes embraced the harsher side of the frontier. Engravings of rugged terrain, Aboriginal camps, and remote outposts circulated widely, both in the colonies and in Britain. These images were often dramatic, even lurid, emphasizing strangeness over serenity. Yet they lacked the intimacy and subtlety that painting could offer. In Perth, where professional artists were few and far between, the line between illustration and art remained porous.

The demand for landscape painting was also shaped by international exhibition culture. Works from Western Australia were sent to colonial showcases in London, Melbourne, and Paris, where they competed not only with other Australian entries but with art from India, Canada, and the Pacific. These exhibitions demanded a kind of visual diplomacy—paintings had to represent Perth as both promising and picturesque. Artistic choices were often shaped by what would appeal to foreign audiences rather than by fidelity to local experience.

Between Frame and Fence: Art as Cultural Claim

Perhaps the most quietly significant aspect of 19th-century landscape art in Western Australia was its role in making land feel owned. To paint a view was, in some sense, to claim it—not just physically but emotionally. The shift from map to landscape painting marked a new phase in the colonial project: one where possession was not only legal or political but aesthetic.

The very act of selecting a vantage point, of cropping and composing, paralleled the logic of fencing and surveying. In this sense, art and agriculture shared a vocabulary. Both aimed to impose coherence on vastness, to replace unpredictability with pattern. Even the visual rhythm of a eucalyptus grove, when painted with care, could echo the rational grid of a settler’s field plan.

Yet some works did resist this harmony. Nicholas Chevalier, a Swiss-born artist who traveled through Western Australia in the 1860s, captured a more ambiguous tone in his landscape studies. His paintings of dry riverbeds and crooked trees carried a latent melancholy—a sense of fragility rather than promise. Though not based in Perth, his occasional depictions of the southwest suggest that not all artists were seduced by the myth of endless bounty.

In the final decades of the 19th century, landscape painting in Perth hovered between decorative ambition and cultural assertion. It rarely challenged colonial assumptions, but it did begin to establish a visual grammar that would shape regional art for the century to come. The bush, once a problem to be solved, became a motif to be interpreted—and eventually, a symbol to be reimagined.

Art and Institutions: Foundations of Public Culture in Perth

By the late 19th century, Perth had begun the slow transformation from remote colonial settlement into a civic-minded city with cultural ambitions. The gold rush of the 1890s poured new wealth into Western Australia, bringing not only miners and merchants but also engineers, architects, journalists, and artists. With that influx came the emergence of the first formal institutions dedicated to the visual arts. These were not incidental developments. They marked a significant shift in how Perth understood its own identity—not merely as a site of extraction or administration, but as a place worthy of aesthetic cultivation and public representation.

The Gold Rush and the Rise of Cultural Philanthropy

The 1890s gold boom was one of the most transformative economic events in Western Australian history. The sudden discovery of rich goldfields in Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie triggered a massive population surge and reshaped Perth almost overnight. Money flowed in from both local success and overseas investment, and with it came a desire—especially among the new wealthy class—to create institutions that mirrored those of Melbourne and Sydney.

This economic confidence found its expression in stone, glass, and oil paint. New buildings rose across the city, often in ornate Federation Romanesque or neo-Gothic styles. Alongside banks, hotels, and public offices came galleries, libraries, and schools—spaces intended not just for function, but for culture. The founding of the Western Australian Museum in 1891 was an early sign of this cultural shift, followed by the establishment of the Western Australian Society of Arts (WASA) in 1896. Though modest in size, WASA played a foundational role in shaping the early art scene of the city.

The Society’s goals were straightforward: to promote appreciation of the fine arts, to hold regular exhibitions, and to encourage artistic education. Its members were a mix of professionals and enthusiastic amateurs, including architects, surveyors, teachers, and wealthy hobbyists. Importantly, the Society created an ongoing platform for local artists to show their work in public, which in turn encouraged the development of a local art market.

One of its earliest champions was Sir John Forrest, the first Premier of Western Australia and a key figure in the post-gold rush development of Perth. A former surveyor and explorer, Forrest understood the symbolic power of public culture. His support for civic beautification included not only infrastructure and landscaping but also the arts. Under his tenure, Perth began to see itself less as an outpost and more as a future capital city.

Among the institutions that benefited from this vision were:

- Perth Technical School (1900): Offered formal instruction in drawing and design, laying the groundwork for future art education.

- Western Australian Society of Arts (1896): Held annual exhibitions and hosted visiting lecturers.

- Early public exhibitions at the Jubilee Building: Displayed works from Britain and the eastern states alongside local painters.

Foundations of the Art Gallery of Western Australia

Though plans for a permanent public art gallery began in the early 20th century, progress was slow. In 1906, a modest collection was established in conjunction with the Museum and Library Board, and a small gallery space was created within the Jubilee Building, itself part of a larger cultural precinct.

The early acquisitions were cautious. The first purchases, drawn from British and colonial artists, reflected conservative tastes: landscapes, portraits, and maritime scenes. There was little interest in the avant-garde or in Australian impressionism, which was gaining traction in the eastern states. Instead, the acquisitions reinforced imperial connections and respectable decorum.

Still, the foundation of the gallery marked a turning point. For the first time, Perth had a dedicated public space for the display of visual art, accessible to a growing urban middle class. It was also a signal of civic maturity—an acknowledgment that culture, not just commerce, belonged in the public square.

Crucially, the gallery’s development was tied to education. The collections were used to train drawing teachers, to inspire technical students, and to offer exposure to artistic traditions far beyond Western Australia. School groups were encouraged to attend, and lectures were delivered on everything from classical composition to the symbolism of Renaissance painting.

The broader public, however, remained ambivalent. For many, art was a luxury or an eccentricity, not an essential part of life. The challenge for early cultural leaders was not only to build institutions but to cultivate an audience. This meant bridging the gap between European traditions and local experience—a task not easily achieved by imported paintings of distant English countrysides.

Local Artists and the First Attempts at a Western Australian Style

As institutions grew, so too did the desire for a recognisable local artistic voice. But what would such a style look like? The landscape was different, the light was harsher, and the cultural context lacked the deep layers of art history that shaped cities like Florence or Paris. For early painters in Perth, the task was to develop a vocabulary suited to Western Australian conditions without abandoning the formal training and expectations inherited from Europe.

Some, like J. W. R. Linton, took a leading role in this pursuit. A former student of the Royal Academy in London, Linton helped establish formal art instruction in Perth and mentored a generation of students, including his own children. He encouraged technical discipline but also urged his pupils to look at their own surroundings—to treat the West Australian bush not as a poor substitute for European forests but as a subject in its own right.

Margaret Johnson, another important early figure, experimented with the color shifts and open compositions dictated by local light. Her watercolours of Cottesloe Beach and Kings Park captured moments of ordinary leisure that, at the time, were rarely considered worthy of serious painting. In doing so, she laid the groundwork for what might eventually become a distinctive Western Australian modernism.

Still, many local artists faced a dilemma: to be taken seriously often meant exhibiting in Sydney or London. The tyranny of distance, combined with a small and conservative local audience, created a pressure to either conform or emigrate. Some did both.

Yet the seeds of a local tradition had been planted. With the support of institutions like WASA and the slowly growing public collection, Perth had begun to construct a visual culture of its own. It was cautious, shaped by imitation and modest aspiration, but it was no longer purely derivative. The early 20th century would see these foundations tested by new movements, new teachers, and the long, slow arrival of modernism.

Modernism Arrives Slowly: Interwar Experiments and Conservative Tastes

In the 1920s and 1930s, while modernist movements reshaped the artistic and cultural landscapes of Europe and the eastern Australian capitals, Perth remained hesitant. The city’s isolation, still considerable even with the advent of rail and steamship links, fostered a lingering conservatism in its public taste and institutional preferences. Here, the academy still reigned. Realism, tonality, and the pastoral ideal continued to dominate exhibitions and instruction, while experimentation found itself relegated to the margins. And yet, even in this cautious environment, modernism did arrive—tentatively, then more forcefully, through émigré artists, rebellious students, and imported influences that began to loosen the hold of traditionalism on the city’s visual culture.

Academic Realism and the Hegemony of Taste

For most of the interwar period, Perth’s art establishment was shaped by a commitment to academic realism and British artistic values. These were reinforced by the continued dominance of institutions like the Western Australian Society of Arts and the Perth Technical School, where teaching emphasized draughtsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and orderly composition. The curriculum bore the influence of the South Kensington system and other British models of technical instruction, which prized control over creativity, discipline over innovation.

This approach appealed to local tastes. Patrons, gallery committees, and the general public viewed realism not only as more beautiful, but also as more respectable. A painting that depicted a recognisable view of the Darling Ranges or a well-executed floral still life was far more likely to be purchased or awarded a prize than one that hinted at abstraction or social critique.

Exhibitions of the period reflect this narrow scope. Reviews from local newspapers such as The West Australian consistently praised “sound technique,” “pleasing colour,” and “fidelity to nature.” Radical tendencies were often dismissed as “eccentric” or “unsettling.” The result was a kind of visual comfort zone—one that mirrored the broader social conservatism of the city during these decades.

Still, there were technical virtues within this traditionalism. Painters like Florence Fuller and Harold Septimus Power, though working within realist conventions, brought a high level of skill and sensitivity to their craft. Fuller, in particular, demonstrated a nuanced handling of light and atmosphere in her portraits and landscapes. Her work straddled the line between realism and romanticism, offering viewers a softened vision of life in the West.

Elise Blumann and the Disruption of the Norm

The first serious challenge to this prevailing order came not from within, but from a migrant: Elise Blumann, a German-born artist who arrived in Perth in 1938 after fleeing National Socialist Germany. Trained in the Expressionist and modernist traditions of Weimar-era Berlin, Blumann brought with her a visual language entirely foreign to the tastes of Perth’s art elite.

Her early works in Western Australia stunned and confused local audiences. Rather than rendering the bush with the soft, golden palette of colonial nostalgia, she employed bold contours, sharp contrasts, and unconventional colours. Her Swan River Landscape (1941), with its abstracted forms and compressed space, was unlike anything previously shown in the city’s galleries. It depicted not a placid view, but a charged encounter between land and artist—a kind of psychic geography.

Blumann’s modernism was not merely formal. It was also attitudinal. She rejected the genteel amateurism that dominated local exhibitions and advocated for a more serious, critical, and professional artistic culture. She lectured, wrote essays, and mentored younger artists, insisting that Perth could not remain an artistic backwater if it wished to be taken seriously.

Her influence, however, was limited by social and institutional resistance. She faced considerable hostility from local critics, some of whom described her work as “alien” or “incomprehensible.” The term “modern” was still often used pejoratively in Perth during this time, connoting not innovation, but pretension.

Still, Blumann’s presence created an opening. Her work forced conversations that had previously been avoided. And over time, her commitment to modernist principles helped seed a new generation of artists who would gradually shift the city’s artistic center of gravity.

The Isolation Problem and the Emergence of the “Perth School”

For artists working in Perth between the wars, one persistent challenge was distance—both geographic and cultural. The tyranny of isolation was not just physical. It was intellectual and professional. There were few opportunities to see contemporary work from Europe or even the eastern Australian capitals. Books arrived late, exhibitions were rare, and critical dialogue was limited. The result was a curious self-reliance that could either insulate or stifle, depending on one’s temperament.

Within this context, a loosely affiliated group of painters began to develop what some later referred to, with mixed affection, as the “Perth School.” These artists—among them Robert Juniper, Guy Grey-Smith (whose maturity came slightly later), and Howard Taylor—shared an interest in exploring the unique conditions of Western Australian light, form, and space. While not a formal movement, they collectively marked a transition away from academic realism and toward a more personal, exploratory engagement with the landscape.

Their work often retained figurative anchors but pushed toward abstraction in composition and mood. Colour was used expressively, not merely descriptively. Brushwork became looser, and negative space more assertive. There was a shared interest in structure and geometry—perhaps a sublimated response to the vastness of the Western Australian environment.

But the isolation remained a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it allowed these artists to work outside the trends and pressures of the Sydney-Melbourne axis. On the other, it made recognition slow and support erratic. Exhibitions were limited to a small local circle. Sales were rare. Public collections were cautious. Many artists were forced to support themselves through teaching or commercial work.

Yet even within this marginal status, something enduring was taking root. The seeds of a distinctly Western Australian modernism—one attentive to space, austerity, and the psychological charge of landscape—were being sown. The full flowering of this vision would come later, in the postwar decades. But its roots lay here, in the quiet defiance of artists like Blumann, the partial turn of realist painters toward abstraction, and the slow widening of the city’s visual horizon.

Boom, Bust, and Boom Again: The Postwar Expansion

The Second World War, with all its brutal interruptions, also served as a cultural rupture in Perth—breaking the inertia of interwar conservatism and creating space for new artistic voices and educational structures. The decades that followed, from the 1950s through the early 1970s, were marked by alternating periods of growth and uncertainty. Yet even amid economic fluctuations and institutional lag, this period saw the emergence of a more confident, diverse, and experimental Western Australian art scene. The shift was neither immediate nor uniform, but it established new foundations upon which contemporary art in Perth would later rise.

A New Pedagogy: The Rise of Curtin and Formal Art Education

Perhaps the most consequential development of the postwar era was the formalization and professionalization of art education. Until mid-century, Perth’s art instruction had largely been confined to part-time technical school courses or private tutelage, dominated by academic drawing and decorative traditions. That began to change with the expansion of tertiary education across Australia, culminating in the establishment of the Western Australian Institute of Technology (WAIT) in 1966—later to become Curtin University.

WAIT’s School of Art quickly became a hub for young artists seeking an alternative to the conservative ethos of Perth Technical School. Here, art was taught not merely as craft but as inquiry. Students were exposed to contemporary movements, encouraged to develop their own visual language, and taught to think critically about the relationship between form, meaning, and society. Sculpture, printmaking, and later photography were integrated into the curriculum, creating a multi-disciplinary environment that broke decisively with the previous generation’s hierarchies.

Key among WAIT’s early contributions was the recruitment of teachers who had studied or exhibited internationally, bringing firsthand experience of abstract expressionism, constructivism, and conceptual practices. Guy Grey-Smith, by now an established modernist voice in Western Australia, was an influential figure during this period—both through his work and through his mentorship. Trained at the Chelsea School of Art in London after recovering from wartime imprisonment and illness, Grey-Smith approached painting as an elemental engagement with landscape: thick, muscular forms rendered in earth-heavy pigments, his canvases grounded as much in geology as in composition.

His influence was complemented by that of Robert Juniper, whose more poetic, mixed-media approach brought a lyrical dimension to postwar modernism in the West. Juniper’s landscapes were less about representation than resonance—evoking space, silence, and the peculiar sense of scale that defines so much of the Western Australian interior. Both artists helped steer the local conversation away from inherited British norms and toward a visual language more suited to the region’s realities.

Mining Wealth, Architectural Modernism, and Corporate Patronage

The postwar decades also saw Perth undergo another economic metamorphosis, this time driven by the mining industry. The discovery and exploitation of vast iron ore reserves in the Pilbara, along with resources such as bauxite, nickel, and natural gas, ushered in an era of state-led infrastructure development and international investment. While the social consequences of this mining boom were complex, its effect on the visual arts was unmistakable.

Public buildings multiplied across the city—courts, libraries, university complexes—and many of them incorporated modernist architecture, which in turn created new contexts for public art. Large-scale murals, sculptural reliefs, and integrated artworks were commissioned as part of civic projects, reflecting the mid-century belief in the unifying power of art and design.

Three prominent examples of this period include:

- The mural work of Howard Taylor, who integrated abstracted natural motifs into civic and educational settings with remarkable subtlety.

- The sculptural installations of Margaret Priest, whose bas-reliefs often adorned public buildings in the Perth CBD.

- Architect-art collaborations, especially with firms like Krantz and Sheldon, who pioneered integrated art-architecture programs.

These commissions marked a shift in how art was encountered: not confined to galleries, but embedded in the fabric of public life. This was art as civic punctuation—meant to elevate the experience of everyday spaces, whether they were bank foyers or council chambers.

Private patronage also began to play a growing role, albeit in selective and often conservative forms. Large corporations based in the resource sector commissioned portraits, sponsored awards, and purchased works to decorate boardrooms and offices. While much of this collecting reinforced safe aesthetics, it nonetheless injected money into the local art economy and helped professionalize artistic careers.

At the same time, a market for private galleries began to develop. Spaces like Skinner Galleries (est. 1958) and later Galerie Düsseldorf offered commercial platforms for Perth-based artists, providing both visibility and a means of financial survival. These galleries operated as cultural outposts—often modest in scale but vital in ambition. They curated, educated, and occasionally provoked, shaping taste at a time when public institutions remained hesitant to move beyond the comfort zone of landscape and portraiture.

The Strain Beneath the Surface: Cultural Lag and Creative Frustration

Despite these advances, the 1950s and ’60s were not an unbroken ascent. Perth remained a relatively small and insular city, and many artists continued to struggle against institutional inertia and audience conservatism. The Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA), though it expanded its acquisitions during this period, was often cautious in its programming. Critics accused it of lagging behind the times—of privileging technical accomplishment over conceptual daring, and of acquiring safe works rather than challenging ones.

Artists frequently left. The magnetic pull of Sydney, Melbourne, or overseas residencies proved too strong for many to resist. Howard Taylor, though he remained in the state, chose to live in near-total seclusion in Northcliffe, where he developed one of the most distinctive bodies of work in Australian art—deeply influenced by the forests, winds, and shifting light of the South West. His isolation, though partly by choice, also reflected the cultural distance many artists felt from the institutional centre of Perth.

This discontent sowed the seeds of the more radical practices that would erupt in the 1970s. The frustration with conservative exhibition spaces, limited critical dialogue, and a slow-moving public sector created a generational divide. Younger artists, educated under modernist teachers but aware of global shifts toward performance, installation, and political art, were ready to push harder. What emerged next would be far messier, more confrontational, and more ephemeral—but it would change the trajectory of Perth art irreversibly.

Yet the groundwork had been laid. The postwar expansion gave Perth what it had previously lacked: infrastructure, education, and the beginnings of a professional art ecosystem. Even its limitations—the very conservatism that sparked rebellion—proved to be catalysts for change. The visual culture of Perth was no longer a provincial appendix. It was becoming a field of contestation, invention, and serious ambition.

The Quiet Revolt: 1970s Counterculture and Conceptualism

By the 1970s, the foundations laid during Perth’s postwar expansion had begun to crack—not from failure, but from tension. A generation of artists trained in modernist techniques and exposed to emerging global trends found themselves increasingly at odds with the structures that had supported their formation. The polite landscapes and civic murals of the 1950s and ’60s were no longer sufficient. Something more restless had taken hold: a desire to reject permanence, to dismantle the frame, and to interrogate not just what art looked like, but what it did. Across studios, campuses, and pop-up exhibitions, Perth entered a period of quiet revolt—one in which concept often displaced craft, and the artist’s gesture became as significant as the object itself.

Praxis and the Rise of the Ephemeral

The 1970s were marked by a decisive shift toward conceptual art, performance, installation, and time-based practices. While these forms were taking root globally—in New York, Düsseldorf, London—their emergence in Perth was shaped by local conditions: isolation, limited market structures, and a cohort of artists who understood that if the traditional paths were blocked, they would have to invent new ones.

At the centre of this shift was Praxis, a short-lived but influential artist-run space founded in 1973. More than just a gallery, Praxis was a declaration: that artists themselves could control the conditions of exhibition, discourse, and support. Housed in an unassuming space in Northbridge, it became a crucible for experimental work that had no home in commercial or institutional venues. Over its decade-long life, Praxis hosted installations, screenings, mail art, and performances—forms of art that were, by definition, difficult to buy, preserve, or commodify.

The artists who exhibited there—among them David Watt, Alex Spremberg, and Jenny Mills—eschewed traditional media and themes in favour of work that explored impermanence, language, and bodily presence. One memorable project involved artists burying sealed packages of text and images in suburban yards, creating an invisible network of artistic intention that resisted both spectacle and consumption.

The mood was one of urgency, but not aggression. This was not a militant avant-garde; it was a community of thinkers and makers who believed that art could still surprise, challenge, and evade capture. In many ways, the conceptual turn suited Perth: a city where the margins were more accessible, where bureaucracy was lighter, and where the risk of failure was real but unpoliced.

Three recurring tendencies defined this new mode of practice:

- Dematerialization: Artworks were often transient or intangible—based on sound, gesture, or action rather than durable form.

- Site specificity: Installations were crafted for particular locations, often outside traditional gallery spaces.

- Artist-led production: Curation, documentation, and promotion were handled by the artists themselves, bypassing gatekeepers.

Perth and the National Avant-Garde

Despite its geographical remove from the cultural centres of Australia, Perth played a more active role in the national avant-garde than is often acknowledged. Key figures from the east coast began to take notice of the city’s experimental vitality. Collaborative exhibitions with artists from Melbourne and Sydney, as well as increasing participation in national forums, positioned Perth not merely as an outlier but as a site of distinct and valuable innovation.

This recognition was hard-won. In the 1970s, Perth was still dismissed by many in the eastern states as culturally provincial, a resource boom town more interested in mining than in meaning. But artists like Brian Blanchflower, with his large-scale, meditative abstraction, and Susan Norrie, whose early paintings from this period flirted with both figuration and conceptual critique, proved otherwise. Their work did not merely echo eastern or international trends; it adapted them to Western Australian conditions—inflected by the state’s landscape, its sense of distance, and its unique light.

The annual exhibitions at the Art Gallery of Western Australia began, slowly, to reflect this changing tide. While the institution remained conservative in many of its collecting practices, its curatorial programs opened up to conceptual and new media work. Temporary exhibitions showcased installation, performance, and photography. Younger curators, influenced by global art theory and by the activism of feminist and post-object movements, brought new energy to the gallery’s programming.

Parallel to this, Curtin University’s art school (still known then as WAIT) became an incubator for critical practice. Its faculty encouraged students to engage not only with materials, but with theory, history, and political context. Lecturers such as Tom Gibbons and Paul Thomas brought academic rigour to discussions of contemporary art, fostering a generation of artists who were intellectually equipped to question the foundations of visual culture.

Still, many artists faced a double challenge: creating work that broke with convention while also building the systems necessary to support it. Documentation—photographs, audio recordings, typed manifestos—became essential. Since the works themselves often vanished after a single performance or installation, it was only through careful archiving that the ideas could be preserved and disseminated.

Public Funding, Protest, and the Limits of Recognition

One of the most significant factors shaping Perth’s art in the 1970s was the rise of public funding, particularly through the newly established Australia Council for the Arts (1973). For the first time, artists had access to grants that could support not only production, but also research, travel, and exhibition. This transformed the possibilities for independent practice—but also introduced new tensions.

While some grants supported vital work, others were subject to bureaucratic misunderstanding or ideological scrutiny. Conceptual and performance-based art, especially when politically inflected, often ran afoul of conservative gatekeepers. Artists had to navigate the delicate balance between provocation and eligibility.

One example of this friction occurred in 1976, when a proposed performance piece involving a mock political protest was denied funding on the grounds of “inappropriate public disruption.” The artists—unnamed in press coverage but likely connected to Praxis—responded with a work that simply documented the process of rejection, turning bureaucracy itself into subject matter. This kind of institutional critique became a hallmark of the era, particularly among artists who saw cultural gatekeeping as just another structure to dismantle.

Yet protest was rarely loud. Perth’s art scene lacked the numbers or media saturation of its east coast counterparts. Its resistance was quieter, more sustained. Instead of banners and manifestos, it offered withdrawal, subversion, or sardonic mimicry. Artists created work that refused to be bought, that existed only for a moment, or that blurred the line between art and life so completely that it became difficult to point to where one ended and the other began.

By the close of the 1970s, Perth’s visual art culture had been fundamentally altered. The changes were not always visible in the city’s streets or in the main rooms of its institutions, but they had taken hold in the studios, artist-run spaces, and university corridors. What emerged was a new understanding of what art in Western Australia could be: not bound by medium or market, but exploratory, provisional, and deeply responsive to its place.

Reclaiming Voice: Contemporary Noongar Art and Urban Identity

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a profound shift occurred in Perth’s visual culture—one that cut against both the colonial frameworks of its art institutions and the conceptual detachment of its modernist era. This shift was not merely stylistic but historical and political: the emergence of contemporary Noongar art as a sustained, assertive, and dynamic force within Western Australia’s cultural life. Long excluded, misrepresented, or tokenized in the city’s visual narrative, Noongar artists began to take central roles—reframing the urban environment of Perth (Boorloo) as a contested, storied, and still-living country.

Double Histories: Christopher Pease and the Recalibration of History Painting

Few artists have done more to disrupt and reframe Perth’s dominant historical imagery than Christopher Pease. A Noongar man born in 1969, Pease studied at Curtin University in the 1990s, emerging at a moment when Indigenous contemporary art—long vital in the deserts, Arnhem Land, and the north—was beginning to assert itself in metropolitan centres as well. Pease’s work, however, is distinctly anchored in place. His subject is not the remote outback but the city itself: its buildings, its archives, its long pretense of newness.

Pease’s large-scale paintings draw heavily on colonial iconography, but he does not mimic it. He interrupts it. In Target I (2006), for instance, a stylized topographic overlay of Perth sits atop a 19th-century rendering of the Swan River settlement, while concentric targets float across the image. The message is clear: the act of mapmaking is also an act of control, and the so-called blankness of the land was never blank at all.

Many of his works incorporate found imagery—engraved plates, architectural plans, botanical drawings—reinserted into compositions that recenter Noongar presence. In Panopticon (2005), Pease overlays the layout of the Fremantle Round House (a colonial prison) with vibrant, sinuous lines that evoke ancestral movements and resistance. The juxtaposition is not didactic but layered: a visual collision between surveillance and story, between grid and songline.

His paintings are not merely responses to history—they are historical documents in themselves. They carry within them both the violence of omission and the power of reentry. Pease does not ask the viewer to admire his technique (though he is technically masterful). He asks the viewer to reconsider what they think they know about where they are standing.

Land, Language, and the Archival Counterattack

Pease is not alone. A growing body of Noongar artists working in and around Perth has challenged the visual erasure of Aboriginal presence in the city, not through nostalgia or victimhood, but through precision, wit, and creative authority. Their work does not depict a “lost” culture; it insists on a continuing one.

Sharyn Egan, a Wajuk Noongar artist and former student of Claremont School of Art, uses sculpture, weaving, and installation to reassert traditional knowledge systems within contemporary settings. Her public commissions often draw on materials such as ochre, paperbark, and balga resin—referencing both ancestral practice and environmental specificity. A key example is her 2016 installation Balga, an arrangement of tall, charred black poles resembling grass trees, which quietly echoed Noongar mourning rituals in the midst of a bustling urban space.

What unites many contemporary Noongar artists is an archival impulse—not to dwell in documents, but to interrogate them. Their art asks: Who made this map? Who wrote this record? What was omitted, and why?

Three strategies frequently appear in this mode of practice:

- Reappropriation: Colonial maps, ledgers, and photographs are taken as raw material, then reinterpreted or subverted.

- Language revival: Noongar words and phrases are embedded into works—textual, sonic, or sculptural—reclaiming naming rights.

- Site activation: Installations or performances are staged at culturally significant locations, transforming urban spaces into places of memory.

This approach can be seen in the work of Peter Farmer, whose large-scale murals and public commissions depict ancestral figures and cultural motifs not as relics, but as active agents within the urban fabric. In his collaborative work at Yagan Square, Farmer integrated Noongar stories and symbols into one of Perth’s most visible civic spaces—reinscribing country within the architecture of the city.

A Country Not Gone: Continuity Over Recovery

Perhaps the most radical aspect of contemporary Noongar art in Perth is its refusal to position itself as a form of repair or recovery. Instead, it asserts continuity. This is not a return but a renewal—an ongoing participation in a world that never ceased to exist, even when ignored.

Ilona McGuire, a younger artist working across mediums, epitomizes this sensibility. In her projection piece Galup (2022), McGuire animated the waters of Lake Monger (formerly known by its Noongar name, Galup), staging a visual remembrance of the violence that took place there during the colonial period. Rather than re-enact trauma for spectatorship, her work suggested that the lake itself remembers. The digital projection was temporary, but its impression lingered: a moment in which landscape, story, and technology briefly aligned.

Such projects reconfigure the idea of site-specific art. In Noongar practice, site is not backdrop—it is the medium. A painting of Kings Park is not just a depiction of trees; it is a statement about Karrgatup, the spiritual and ceremonial site long overwritten by lawn and path. A sculpture at Elizabeth Quay does not simply decorate public space; it contends with the deep histories beneath the concrete.

These works demand that Perth be seen not as a young city growing upward, but as a layered place with long, contested roots. They transform the idea of the city itself—from neutral backdrop into active participant, from settler invention into shared ground.

Crucially, this wave of contemporary Noongar art has done more than critique. It has shaped institutions. Noongar curators, educators, and advisors now play key roles in museums and galleries across the city. Initiatives like the AGWA Indigenous Advisory Panel and the development of dedicated cultural precincts signal a deeper shift—not merely toward inclusion, but toward influence.

And yet, the challenge remains ongoing. Urban land remains tightly controlled, public commissions competitive, and market interest uneven. But the foundation has changed. Noongar artists are not asking for entry; they are building and reshaping the house. Their art is not a supplement to Perth’s visual culture—it is its originating, enduring, and future-facing form.

Artists in Isolation: Distance as Both Hindrance and Freedom

The phrase “most isolated capital city in the world” has long followed Perth like an affectionate insult, a badge of rugged independence or an excuse for being overlooked. For visual artists working in Western Australia, this isolation has often felt more like a structural condition than a poetic flourish. It shapes careers, curtails opportunities, and imposes logistical burdens—whether in the form of freight costs, sparse audiences, or geographic exclusion from national conversations. Yet for many, isolation has also provided something rarer: space. Time. The freedom to work without constant surveillance or fashion. Perth’s distance from the traditional art centres has, paradoxically, allowed certain practices to develop with exceptional clarity and integrity.

Between Silence and Scale: The Solitude of Howard Taylor

No artist embodies the generative power of Western Australian isolation more completely than Howard Taylor (1918–2001). Though his early career took him briefly to London, where he studied at the Birmingham College of Art after surviving a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, Taylor spent most of his adult life in Northcliffe, a small town deep in the South West forests. There, surrounded by karri trees and shifting weather, he developed a body of work that resists classification—part sculpture, part painting, part optical experiment, all anchored in his phenomenological engagement with place.

Taylor’s work was intensely local yet universally resonant. He rarely depicted specific scenes; instead, he worked to understand light, form, and the subtle shifts that occur as one moves through space. His wall-mounted sculptures—painted wooden panels shaped with architectural precision—invite viewers not to look at an image, but to attend to perception itself. They reward slowness, asking the viewer to notice how colour behaves differently in shadow, how curves disappear and reappear depending on angle and distance.

In interviews, Taylor often described his surroundings not as inspiration, but as environment—as something to move through, respond to, and be disciplined by. The forest was not picturesque; it was structure. It taught him the limits of seeing. His artistic isolation was not a retreat but a deliberate choice, a refusal to participate in the noise of metropolitan taste-making.

Three features of Taylor’s practice illustrate the possibilities of geographic distance:

- Process over product: His work was built slowly, often over years, with little concern for market cycles or trends.

- Material intimacy: Wood, paint, and pigment were handled with the care of a builder or gardener, rather than a studio-bound technician.

- Experiential depth: His pieces were meant to be inhabited—more installation than object.

Taylor was not alone in embracing the peripheral. Artists such as Philippa Nikulinsky, whose intricate botanical illustrations are drawn from deep field immersion, and David Gregson, whose emotionally charged portraits and abstracts evoked the psychological weather of Perth’s postwar years, also worked largely outside the orbit of national institutions, shaping careers grounded in place rather than profile.

To Stay or to Leave: The Perth Dilemma

For many artists, however, Perth’s remoteness remains a source of professional tension. The decision to stay or to leave haunts nearly every serious practitioner at some point in their career. The local art economy is small, its collector base limited, and its critical infrastructure thin. While institutions like AGWA and PICA offer support, they cannot match the scale or visibility of Sydney and Melbourne.

As a result, countless Western Australian artists have felt compelled to relocate. Some, like Susan Norrie, found international success after moving east. Others have maintained dual identities—based in Perth but exhibiting globally. The recent careers of Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Abdul Abdullah, brothers who grew up in Perth and still have strong ties to the city, illustrate this tension well. Their work—often large, provocative, and politically charged—has been shown across Asia, Europe, and North America, but its conceptual backbone remains tied to the cultural specificity of growing up Muslim, Malay, and Australian in suburban Perth.

For artists who stay, the rewards can be substantial, but the costs are real. Exhibitions receive less coverage. Travel eats into budgets. Collaborations take extra planning. Even shipping a painting to Melbourne for an art prize can feel like a logistical gauntlet.

Yet for all its frustrations, staying also allows something increasingly rare: artistic focus. The distractions of trend-chasing, critical fashion, and institutional positioning are muted. Artists can develop slowly, privately. The city’s relative quietude offers both a buffer and a proving ground. When risk is taken in Perth, it is usually taken in earnest, without the safety net of media spectacle.

Isolation as Motif and Medium

Beyond its logistical implications, isolation has also become a motif in the work of many Perth artists—a psychological and aesthetic condition explored rather than avoided. The city’s physical layout, climate, and social rhythms often surface in the form of sparse compositions, reflective pacing, and restrained emotional registers.

The painter Trevor Richards, for example, builds abstract geometric canvases that echo the rational grids of suburban planning but imbue them with unease. His palettes—dusty oranges, muted greys, bleached whites—suggest the tonality of Perth’s built environment: concrete walls under midday sun, pale sands, vacant car parks. These are not paintings “about” Perth, but they could not have been made elsewhere.

Similarly, the photography of Bo Wong captures the subtleties of light and texture in Western Australia’s art and architecture, often focusing on the overlooked: a shadowed corner of a studio, a detail in a handmade object. Her work forms a kind of meta-art practice, documenting the conditions of artistic life in a place where distance is both defining and productive.

Even the city’s artists who engage with global themes—climate change, migration, digital identity—do so with an awareness of their position on the cultural margin. There is a humility in this stance, but also a distinct sharpness: a refusal to merely echo international trends without adapting them to local terms.

Perth’s isolation, then, is not simply a constraint. It is an aesthetic category, a mode of working, a conceptual frame. It encourages independence of thought, resistance to fashion, and—perhaps most of all—a deep attentiveness to place. While many artists will continue to leave, and some will return, the city remains an unusual crucible: a site where solitude is not always a curse, and where distance can be the condition of vision.

Biennials, Booms, and the Business of Art in the 2000s

At the turn of the 21st century, Perth found itself in the grip of another economic surge—driven by China’s appetite for Australian minerals and the vast expansion of resource extraction across the Pilbara. Once again, prosperity reshaped the city’s skyline and civic ambitions. This time, however, the boom brought with it not just highways and high-rises, but a more sophisticated appetite for cultural capital. Art, increasingly, was seen not only as a reflection of civic life but as a tool of urban branding, economic diversification, and international positioning. The result was a peculiar blend of opportunity and compromise: more galleries, more money, more exposure—alongside new pressures, new exclusions, and a different kind of conservatism, dressed in the language of innovation.

The Festival Era and the Visual Turn

While Perth had long been home to the Perth International Arts Festival (PIAF), its focus in the 20th century leaned heavily toward music, theatre, and literature. But in the early 2000s, under the artistic direction of figures like Lindy Hume and Shelagh Magadza, the Festival began to take visual art more seriously—commissioning large-scale installations, outdoor projections, and site-responsive exhibitions that extended beyond the traditional gallery walls.

One key moment was the 2002 commission of Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s Sip My Ocean, a lush, immersive video installation that transformed the Art Gallery of Western Australia into a sensorial dreamscape. Though Rist was an international figure, her work’s reception in Perth signaled that local audiences were ready for contemporary, experimental, and non-object-based art. Following this, a growing number of visual art commissions were folded into the Festival, often drawing on local talent to activate urban and natural spaces in new ways.

These interventions coincided with a global shift toward the festivalization of art—a trend in which biennials, triennials, and seasonal events became central to how cities projected cultural relevance. Perth, though small by global standards, positioned itself to participate in this circuit. Satellite events such as Spaced (a recurring program of artist residencies across regional Western Australia) and Fremantle’s Hatched exhibition for emerging artists helped feed this ecosystem, offering pathways for younger practitioners to gain exposure beyond their home state.

But as with many festival models, the benefits were uneven. While public engagement increased, many artists found the short-term nature of commissions—designed for spectacle, not permanence—limiting. The demands of constant novelty sometimes worked against deeper, slower forms of artistic development. Works had to be photogenic, mobile, and immediately legible to a broad public—criteria that did not always suit the most ambitious or challenging practices.

Cultural Branding and the Sculptural Skyline

Alongside the rise of festivals came a new phase of urban redevelopment. Projects like Elizabeth Quay, the Perth Cultural Centre, and the Northbridge Link aimed to reconfigure the city’s spatial logic—knitting together disparate zones, attracting tourism, and projecting an image of Perth as a “global city.” Art was central to these visions.

Public sculpture, in particular, became the symbolic language of this new urban identity. The most visible example was Spanda (2016) by Christian de Vietri, a towering white steel ellipse located at Elizabeth Quay. Commissioned by the Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority and reportedly costing over $1.3 million, the work divided public opinion. Some praised its formal elegance and metaphysical references; others derided it as vacuous civic ornament. Either way, it became a lightning rod for debates about the value of public art, the aesthetics of corporate redevelopment, and the visibility of local artists in major commissions.

More broadly, the proliferation of public artworks in the 2000s reflected a shift in how art was being positioned. It was no longer merely a cultural good; it had become a form of infrastructure. Like bridges, bike paths, or boutique bars, art was now part of the planning lexicon—used to activate underutilized spaces, encourage pedestrian traffic, and differentiate Perth from its rivals.

Three tendencies defined this phase of civic cultural investment:

- Art as amenity: Sculptures and murals were integrated into planning guidelines as enhancements to public space.

- Place-making rhetoric: Projects used buzzwords like “activation,” “vibrancy,” and “engagement” to justify investment.

- Internationalism over localism: Major commissions often went to overseas artists, sidelining Western Australian practitioners.

While some public artworks genuinely transformed their environments, others felt tokenistic or disconnected from place. The tension between art as expression and art as strategy became increasingly apparent, raising questions about who art was for, and who it represented.

The Commercial Turn: Private Galleries and Art as Asset

As public funding fluctuated—and often lagged behind Perth’s economic growth—the private sector began to fill some of the gaps. A new generation of commercial galleries emerged in the 2000s, including Mossenson Galleries, Linton & Kay, and Turner Galleries. These spaces offered platforms for contemporary artists working across media, from figurative painting to new media installations.

Importantly, the rise of private galleries coincided with the growing interest in art as investment. As property markets boomed and disposable incomes increased, collecting became fashionable among Perth’s professional classes. Art fairs, auctions, and corporate collections expanded, and artists began to tailor their practices—consciously or not—to this shifting economic terrain.

This commercialization had both benefits and costs. On the one hand, it created new revenue streams and audiences. On the other, it subtly reshaped the ecology of production. Certain styles—slick, ambiguous, decorative but “edgy”—found easier passage into the commercial circuit, while more experimental or overtly political work struggled for placement. The language of critique risked becoming subsumed by the language of branding.

Even among institutions, this shift was felt. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, under various leaderships, attempted to modernize its image through blockbuster exhibitions, rebranding campaigns, and the refurbishment of key spaces. While these efforts brought greater visibility and foot traffic, they sometimes alienated artists who felt that institutional support for local practice had become secondary to reputation management.

Still, the 2000s were a time of significant expansion. Perth’s visual art scene grew in scale, confidence, and international connectivity. Artist-run spaces like Moana Project Space and Paper Mountain offered alternatives to the commercial and institutional spheres, sustaining a parallel ecosystem of experimental work and peer-led support. Cross-disciplinary collaboration—between art, architecture, music, and design—flourished, reflecting the increasingly hybrid nature of contemporary practice.

Yet the question remained: Could this growth be sustained? Or was it tethered too tightly to the cycles of resource extraction, real estate speculation, and city-branding initiatives that had driven it?

By the end of the decade, cracks were beginning to show. Funding tightened. Festivals lost momentum. The global financial crisis tested the limits of cultural philanthropy. Still, the infrastructure had been built. What remained was to see how—and whether—it could adapt.

Space, Sunlight, Suburbia: The Aesthetics of Perth Itself

Artists in Perth have always faced a curious paradox. On the one hand, they contend with the city’s reputation for isolation, blandness, and suburban sprawl—a place allegedly short on cultural intensity or visual interest. On the other, those very qualities—its strange spaciousness, merciless sunlight, and endless rows of fibro houses or glass towers—form a physical and psychological environment unlike any other in Australia. For those willing to look closely, Perth is not a blank canvas, but a difficult and revealing one. Its aesthetic is subtle, often evasive, but it runs deep. In the hands of its most attentive artists, Perth becomes a subject not of glamour or myth, but of perceptual acuity.

Light as Pressure: Painters of the Western Sun

Perth’s light is unlike that of Sydney or Melbourne. It is harder, flatter, less forgiving. Midday shadows fall like razors. Colour bleaches quickly. Painters working in this environment often describe it not as inspiration but as pressure—something that forces simplification, abstraction, or radical tonal control.

This distinct chromatic climate gave rise to what might be called a “Perth palette”: dry ochres, sharp whites, desaturated greens, pale pinks, and mineral greys. These tones recur not just in landscape painting, but across disciplines. They reflect a city where the built and natural environments often blur—where gum trees abut brick veneers, and suburban fencing extends into bushland without transition.

Helen Smith, a founding member of the artist-run space and collective Galerie Düsseldorf, exemplifies this chromatic economy. Her minimalist paintings and digital works often restrict themselves to narrow tonal ranges, playing with repetition, optical rhythm, and architectural precision. There is a quietness to her work that mirrors the experience of walking through an outer Perth suburb at dusk—orderly, sun-bleached, and just slightly uncanny.

The late Howard Taylor, revisited here from a new angle, treated Perth’s light not as a backdrop but as a medium. In his sculptures and shaped panels, the angle of illumination was often as important as the pigment. His entire practice can be read as an extended inquiry into how light behaves in this place—not metaphorically, but physically, spatially, almost chemically.

For many Western Australian painters, the challenge is not to dramatize the light but to withstand it. Shadows are not soft. Colours do not blend easily. The land does not yield painterly compositions in the European sense. The bush is too dense or too monotonous. Composition, in Perth, often comes down to discipline: where to stop, what to leave out, how to handle flatness without collapsing into dullness.

Suburban Form: A Visual Logic of Repetition and Discontinuity

If Perth’s light resists traditional beauty, its suburbs resist traditional narratives. Unlike older cities shaped by historical layering or urban density, Perth grew outward—rapidly, repetitively, and in response to modern planning rather than historical evolution. The result is a landscape of sameness punctuated by sudden variation: cul-de-sacs ending in bushland, shopping centres adjoining wetlands, housing estates indistinguishable from each other except by name.

This suburban condition has had a profound impact on the city’s artists—not always directly, but as a kind of unspoken architecture of perception. Trevor Richards, whose geometric abstractions we encountered earlier, takes his visual logic from tiled rooftops, brick walls, and road layouts. His paintings are not representations of the suburbs but translations of their structural repetition into visual rhythm.

Perth’s photographic artists have also responded to this spatial oddity. Jacqueline Ball’s large-format images capture the tension between built form and open land with quiet intensity. In her series Periphery, she documents industrial zones and vacant lots at the city’s edges—spaces that are neither city nor country, built nor wild, but suspended in visual ambiguity.

Others, like Graham Miller, explore the emotional register of suburbia. His cinematic photographs, often shot at twilight, depict ordinary Perth streets and figures with the melancholy of American small-town noir. A parked car, a verandah light, a single tree in silhouette—these become sites of psychic projection, as if the surface of the city were quietly harbouring dreams or disappointments.

Three aesthetic features recur in this suburban response:

- Modularity: Repetition of form—be it in rooftops, fences, or facades—is mirrored in compositional structure.

- Liminal spacing: Artists focus on thresholds—driveways, alleys, boundary lines—rather than centres.

- Emptiness as subject: Stillness and vacancy are treated not as absences but as moods in themselves.

The result is an aesthetic that feels neither utopian nor dystopian. Perth’s suburban art rarely criticises or idealises; instead, it observes. It pays attention. It lingers on the surfaces that most viewers ignore.

A City That Doesn’t Show Off

One of the most consistent challenges in defining a “Perth aesthetic” is that the city resists spectacle. It lacks the architectural swagger of Sydney or the historical romance of Melbourne. Its central business district is functional rather than iconic. Even its coastline, though celebrated, is sparse in built form. There is no Bondi Pavilion, no St Kilda Pier. There are just dunes, carparks, and the long line of the Indian Ocean.

For many artists, this restraint has become a virtue. Perth is not a city that shows off, so its art has learned to look inward, or outward, but rarely upward. It draws from the periphery, the overlooked, the quiet. It is anti-monumental in spirit.

This sensibility found expression in the architecture of Iwan Iwanoff, the Bulgarian-born modernist who lived and worked in Perth from the 1950s until his death in 1986. Though not an artist in the traditional sense, Iwanoff’s buildings—residences in Dianella, Floreat, and City Beach—were sculptural, expressive, and oddly aligned with the visual temperament of Perth’s artists. They treated light as substance and surface as rhythm. Their boldness was local: eccentric but not ostentatious.

Contemporary artists have often taken cues from this ethos. Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s meticulously carved sculptures of animals and domestic spaces are emotionally grand but formally restrained. They carry within them a suburban sublimity—gestures of grief, wonder, and memory rendered in the idioms of everyday life.