In the heart of Seville stands one of Europe’s most extraordinary palaces—the Real Alcázar, a royal complex that has borne witness to over 1,000 years of history, religion, and artistic expression. Originally constructed in the early 10th century as a Moorish fortress, the Alcázar has evolved into a layered masterpiece, blending Islamic, Christian, and Renaissance architectural styles in a single, coherent structure.

Still used today as the official residence of the Spanish royal family when in Seville, the Alcázar is the oldest royal palace in Europe still in use. Its architecture is a reflection of Spain’s complex past—from Muslim rule and the Reconquista, to Catholic monarchs, Habsburg expansion, and Bourbon embellishment. Few buildings capture this evolution with such elegance.

The name “Alcázar” comes from the Arabic al-Qasr, meaning “the castle” or “the palace.” Yet the structure is far more than a military fort. With its lush gardens, intricate tilework, ornate arches, and golden ceilings, it feels more like a dream in stone—a place where artistic worlds collided and created something utterly unique: Mudéjar architecture, a Christian style infused with Islamic aesthetics.

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987 (along with Seville Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies), the Alcázar draws visitors from around the world who come not only for its history, but for its living beauty. It remains a palace in use, a work of art in progress, and one of the most captivating architectural ensembles in all of Spain.

Moorish Foundations: The Islamic Alcázar

The earliest roots of the Alcázar go back to the 10th century, when the Umayyad dynasty of Córdoba constructed a fortress on the site of a Roman and Visigothic settlement. Known as the Al-Muwarak (The Blessed Palace), it was part of the larger expansion of Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled region of the Iberian Peninsula. The original function was administrative and military—serving as a residence for Muslim governors and a center of political power.

Built primarily from brick, plaster, and wood, early Islamic structures at the Alcázar emphasized geometry, proportion, and interior courtyards, following classical Islamic models. Horseshoe arches, intricate stucco work, and patterned tile began to define the complex’s aesthetic identity. Water played a central role, with fountains, pools, and irrigation channels providing both beauty and cooling in Seville’s intense heat.

In the 11th century, under the Abbadid dynasty, the Alcázar was further developed and beautified. King Al-Mu’tamid, the last Abbadid ruler, transformed the complex into a cultural and poetic hub. He constructed new courtyards and palaces that reflected the refined taste of Andalusian court life. Though little of these early buildings survive intact, their influence can still be felt in the later structures.

After the Christian conquest of Seville in 1248 by Ferdinand III of Castile, the Alcázar was not destroyed—it was adapted. Christian kings saw the beauty of Islamic architecture and preserved much of what they found, incorporating it into their own residences. This choice set the stage for Mudéjar architecture, a uniquely Iberian blend of Islamic motifs and Christian patronage.

Today, the oldest surviving parts of the Alcázar are still rooted in this Islamic past. The Patio del Yeso and the Hall of Justice (Sala de la Justicia), both located in the Palacio del Yeso, retain original Almohad elements from the 12th century, including horseshoe arches, Kufic inscriptions, and early plaster ornamentation.

The Mudéjar Masterpiece: Pedro I and the Palacio de Don Pedro

The most celebrated section of the Alcázar was built during the reign of Pedro I of Castile, also known as Pedro the Cruel, who ruled from 1350 to 1369. Although a Christian monarch, Pedro admired the refined aesthetics of Al-Andalus and employed Granadan and Toledan Muslim artisans to design and build a palace within the Alcázar that would rival any Islamic court.

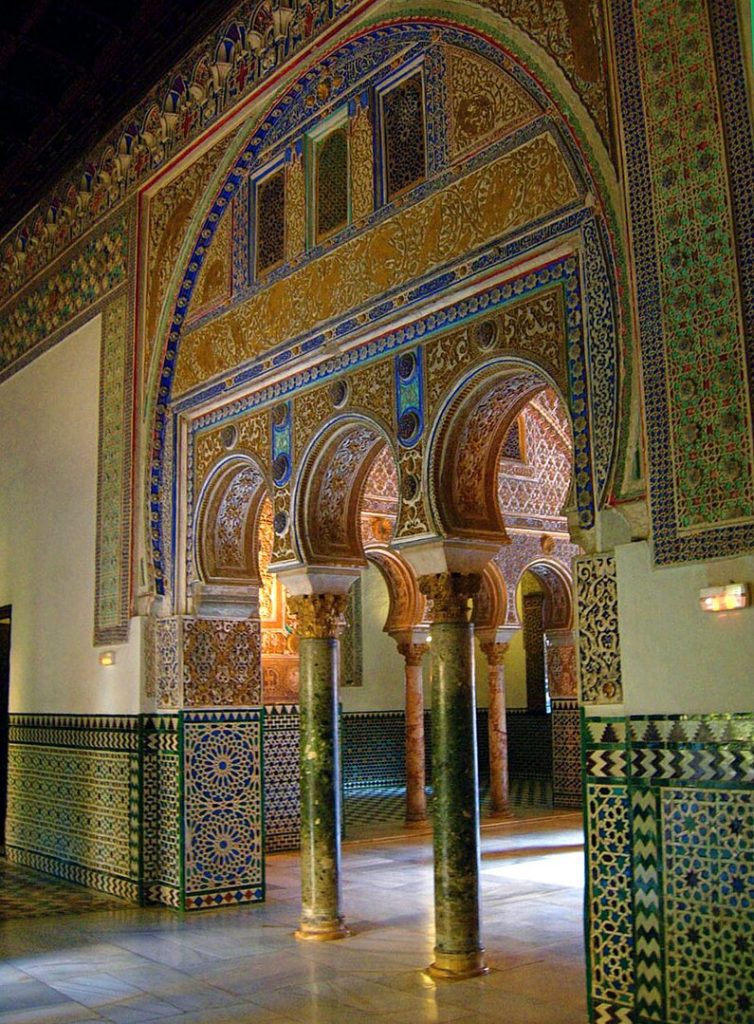

The result was the Palacio de Don Pedro, completed around 1364, a structure that stands as one of the greatest examples of Mudéjar architecture in the world. It combines Islamic craftsmanship with Christian iconography, royal heraldry, and Gothic structural elements in a seamless architectural fusion.

The entrance to the palace, the Puerta del León (Lion’s Gate), leads into a world of intricate detail. The interior features horseshoe and scalloped arches, muqarnas (honeycomb vaulting), tile mosaics (azulejos), and inscribed Arabic calligraphy. Ironically, much of the Arabic writing praises Pedro as a just and mighty king—written by Muslim artisans under Christian rule.

The centerpiece of this palace is the Patio de las Doncellas (Courtyard of the Maidens). Surrounded by arcades of stucco arches and crowned with an upper gallery of Renaissance additions, the courtyard centers on a long rectangular reflecting pool. Recent restoration revealed an original sunken garden, likely used to cultivate aromatic herbs and flowers, enhancing the sensory richness of the space.

Another highlight is the Salón de Embajadores (Hall of Ambassadors), used for royal audiences and ceremonies. Its magnificent golden dome, added in 1427, is made of gilded wood arranged in an intricate star pattern and supported by richly carved stucco walls. Every surface is adorned with Islamic geometry, Christian symbols, and Pedro’s own motto: “Yo soy el rey don Pedro, justiciero” (I am King Don Pedro, the Just).

This palace wasn’t just an architectural marvel—it was a political statement. By commissioning a palace that matched or surpassed Islamic grandeur, Pedro positioned himself as both a Christian king and a worldly, enlightened ruler. His vision gave birth to the Alcázar’s most iconic space.

Gothic and Renaissance Additions: Catholic Monarchs and Charles V

Following the Reconquista, successive Catholic monarchs continued to use and transform the Alcázar. While they preserved Mudéjar elements, they also introduced new architectural styles aligned with European trends. The result was a series of Gothic and Renaissance renovations, particularly under the reigns of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, and their grandson, Charles V.

In the 15th century, the Casa de la Contratación (House of Trade) was founded within the Alcázar complex. This institution oversaw Spain’s commerce with the Americas and helped make Seville one of the wealthiest cities in Europe. Its buildings were constructed in a late Gothic style, with high, vaulted ceilings, ribbed arches, and ornate stone carvings.

Charles V (also Holy Roman Emperor) left an especially strong architectural legacy. In 1526, he commissioned a new suite of rooms for his wedding to Isabella of Portugal, blending the existing Mudéjar forms with Italian Renaissance features. These rooms, known as the Cuarto del Emperador, include coffered ceilings, classical pilasters, and marble columns—clear signs of Renaissance influence imported from Italy.

The Admiral’s Hall (Salón del Almirante), part of the Casa de la Contratación, features Gothic ribbed vaults and housed the Council of the Indies. It was here that explorers and traders, including Christopher Columbus, negotiated terms and reported their discoveries to the crown. Though its interior is relatively austere, its architectural importance is immense.

The Renaissance additions did not erase the past—they were layered onto it. Builders often incorporated older Mudéjar elements into newer rooms, creating a dynamic interplay between architectural epochs. The Alcázar thus became a palimpsest, where Gothic vaults, Islamic tile, and Renaissance stone exist side by side, harmonizing rather than clashing.

Baroque and Bourbon Influences: 17th to 18th Century Enhancements

While the Alcázar’s architectural golden age occurred between the 10th and 16th centuries, its evolution didn’t stop there. During the Baroque period, the palace complex was updated to meet the aesthetic and functional demands of the time, particularly under the Bourbon dynasty, which succeeded the Habsburgs in the early 18th century.

The 17th century saw minor but meaningful additions to the Alcázar’s layout, including improvements to gardens, staircases, and courtyards. Architects and decorators favored more dramatic contrasts, bold stucco work, and ornamental ceilings. Some of these elements can be found in secondary halls and living quarters used by Spanish royals for short-term stays or administrative functions.

With the arrival of Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain, in the early 1700s, French tastes began to influence Spanish palatial design. Though the Alcázar was not radically rebuilt—unlike many older palaces elsewhere—it was refined. Interiors were updated with Baroque stucco cornices, painted ceilings, and more elegant furnishings. These changes reflected the centralized, modernizing spirit of the Bourbon monarchy.

The Salon de Carlos V (Charles V Hall), already built in the 16th century, received Baroque embellishments in the form of new tiling patterns and painted medallions. Fireplaces were added to several rooms, a nod to increasing comfort in royal quarters. The royal bedrooms and reception rooms were also adjusted to match newer standards of courtly decor.

Another enduring Baroque touch is seen in the elaborate ironwork and gates scattered throughout the palace. Hand-forged gates, window grilles, and lantern holders—ornate but functional—were installed across the complex, enhancing its stateliness without undermining its older Islamic and Gothic framework.

Even as it was updated, the Alcázar remained a palace of palimpsests, never overwritten but continually layered. This restraint, uncommon among European monarchies that favored total redesign, is what has preserved the Alcázar’s unique architectural dialogue between centuries.

The Alcázar Gardens: Geometry, Water, and Paradise

No description of the Alcázar would be complete without its gardens, which extend over seven hectares and are an integral part of the palace’s architectural and symbolic identity. Built in successive phases, these gardens reflect Islamic, Renaissance, and Baroque influences—each layered onto one another in a dazzling fusion of nature, geometry, and design.

The Islamic gardens of the early Alcázar followed the traditional concept of “chahar bagh”, or four-part paradise garden. These early layouts emphasized symmetry, flowing water, and aromatic plants. Channels known as acequias and fountains were used to both cool the air and create a calming sensory experience. The Patio de las Muñecas and Patio del Yeso retain these early design elements in miniature.

With the Renaissance, larger and more structured gardens were developed. Under Charles V and subsequent monarchs, the Jardines de Mercurio, Jardín del Príncipe, and Estanque de Mercurio (Mercury’s Pond) were added. The pond, built atop a former Almohad cistern, became the centerpiece of the garden complex. The bronze statue of Mercury, added in the 16th century, gazes down upon tiled fountains, topiary hedges, and reflective pools.

Baroque elements were introduced later, especially in the Galería de los Grutescos (Grotto Gallery), designed in the 17th century. This elevated walkway, built on the remains of the old Almohad wall, offers a sweeping view of the gardens and is decorated with artificial grottos, shells, and painted stonework to create a sense of fantasy and delight.

Notable Features in the Alcázar Gardens:

- Mercury’s Pond – A Renaissance water feature with a bronze statue of Mercury and tiled basin.

- Grotto Gallery – A 17th-century Baroque arcade overlooking the gardens, featuring artificial grotto ornamentation.

- Labyrinth Garden – A playful and symbolic Renaissance addition, meant to entertain and instruct.

- Palm and Orange Groves – Retained from Islamic design traditions, offering fragrance and shade.

- Water channels and fountains – Used for cooling and sound, echoing Islamic paradise garden traditions.

The gardens serve not only as places of rest and beauty but as extensions of the palace’s philosophy—bringing order to nature, reflecting divine harmony, and linking the man-made to the eternal. Their design, like that of the palace itself, is never static and continues to evolve.

Modern Use, Conservation, and Cultural Legacy

In modern times, the Alcázar continues to function as both a royal residence and a national monument. The Spanish royal family still uses parts of the upper palace (especially during visits to Seville), while the remainder of the complex is open to the public and serves as a premier tourist destination, drawing over 1.5 million visitors annually.

Preservation and restoration of the Alcázar are handled by a dedicated city commission in collaboration with national heritage authorities. Great care is taken to preserve the building’s multi-layered character. Whether restoring 14th-century stucco, 16th-century coffered ceilings, or Baroque gates, artisans strive to use traditional materials and techniques where possible. Archaeological excavations are ongoing, especially in the oldest Islamic sections, revealing more about the palace’s hidden past.

The Alcázar has also served as a filming location, most famously as the Water Gardens of Dorne in HBO’s Game of Thrones. This exposure brought global attention to the site but also raised concerns about overcrowding and preservation. In response, visitor limits and guided tour options have been introduced to better protect the structure and grounds.

In terms of cultural influence, the Alcázar represents more than just architecture—it embodies Spain’s complex identity. It is a place where Muslim, Christian, and Jewish histories meet. It tells a story not of destruction and replacement, but of continuity and adaptation. It reminds visitors that great beauty often comes from the blending of cultures, not their separation.

Today, whether viewed through the lens of art, architecture, or history, the Alcázar stands as one of Europe’s most unique and compelling palaces—a testament to centuries of vision, craftsmanship, and coexistence.

Key Takeaways

- The Alcázar of Seville began as a Moorish fortress in the 10th century and evolved into a Christian royal palace.

- The Palacio de Don Pedro is a world-class example of Mudéjar architecture, built by Muslim artisans for a Christian king.

- Later additions reflect Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque influences, especially under Charles V and the Bourbon kings.

- The palace gardens blend Islamic, Renaissance, and Baroque landscape design, creating a paradise on earth.

- The Alcázar remains an active royal residence and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, carefully preserved for modern generations.

FAQs

- When was the Alcázar of Seville originally built?

It began as a Moorish fortress in the early 10th century under the Umayyad Caliphate. - What architectural style is the Alcázar known for?

Mudéjar, a blend of Islamic and Christian styles, is the most distinctive, but Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque elements are present. - Is the Alcázar still used by the Spanish royal family?

Yes, it is the official residence of the monarchy in Seville and still used during visits. - What is the Patio de las Doncellas?

A central courtyard in the Palacio de Don Pedro featuring Islamic arches, a reflecting pool, and Renaissance upper galleries. - Can you visit the Alcázar gardens?

Yes, the expansive gardens are open to the public and include fountains, sculptures, and formal landscaping from various eras.