The art history of New Mexico is not merely a story of regional aesthetics but a dense record of habitation, rupture, continuity, and reimagination—etched, built, painted, and performed across a landscape both austere and extravagant. To understand New Mexico’s artistic lineage is to trace not a linear progression but a palimpsest of cultures layered atop one another: ancestral Puebloan civilizations whose geometric forms echoed celestial rhythms; Franciscan friars imposing sacred narratives in pigment and timber; itinerant santeros carving divine intercessors in mountain villages; modernists seeking transcendence in bone and light; and contemporary artists navigating the complex aftermath of centuries of appropriation and persistence.

Geography alone does not explain this richness, but it sets the stage. New Mexico occupies a liminal zone—both literally and metaphorically. It is a frontier in every historical sense: northernmost outpost of the Spanish empire, peripheral territory of the Mexican Republic, an ambiguous possession of the expanding United States, and now a symbolic margin within American art history. Its deserts and mountains were never empty, nor its aesthetic traditions accidental. Instead, they represent a dynamic field of cultural negotiation. The visual expressions that emerged here bear the weight of encounter: between indigenous cosmologies and Catholic monotheism, between folk devotion and elite taste, between isolation and intrusion.

Unlike the coastal metropoles of the United States, New Mexico’s artistic traditions were never severed from the pre-modern world. Even as European art underwent its spasms of revolution—in Baroque illusionism, Enlightenment classicism, Romantic rupture, or modernist purity—New Mexico’s artists often labored in conditions of stasis and inheritance. Forms repeated over centuries, materials persisted, and iconographies returned with liturgical regularity. Yet this should not be mistaken for artistic inertia. The art of New Mexico has always been about endurance—not in the passive sense of surviving—but in the active sense of sustaining meaning, presence, and beauty under conditions of rupture.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the interplay between the region’s oldest and newest art. The carved kivas and cliff dwellings of Chaco and Mesa Verde find strange but resonant echoes in the reductive geometries of the Transcendental Painting Group. The retablos of anonymous santeros, with their frontal saints and luminous gold fields, can be seen reflected in the stylized figuration of 20th-century Native artists confronting the iconographies of ethnographic display. Even the bleached skulls and eroded mesas painted by Georgia O’Keeffe were not mere abstractions of the Southwest, but forms dense with accumulated visual and spiritual residue.

What makes New Mexico singular in the American artistic imagination is the longevity of its traditions and the porousness of its cultural boundaries. It is a place where modernist aesthetics and devotional craft, indigenous symbology and European allegory, abstraction and figuration, sacred and profane, all coexist in a tension neither resolved nor easily categorized. The region’s art is not a relic of the past but an archive of living contradictions—constantly reinterpreted, revived, or commodified depending on the viewer’s angle.

The following sections will pursue this visual history from its prehistoric origins to its contemporary expressions. This journey will not flatten difference, nor idealize hybridity, but rather take seriously the specificity of New Mexico’s cultural collisions and artistic survivals. To study its art is not to discover a marginal appendix to American art history, but to confront one of its most revealing cores—where questions of tradition, identity, land, and vision have always been paramount.

Ancestral Foundations: The Art of the Ancient Pueblos

Long before European maps charted the interior of the North American continent, the land we now call New Mexico was home to one of the continent’s most enduring and sophisticated artistic cultures. The ancient Pueblo peoples, whose descendants include the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and numerous Rio Grande communities, developed a visual and architectural language deeply attuned to cosmology, materiality, and environment. This art, far from decorative, was integrally woven into ritual, subsistence, and social order. It reveals a complex aesthetic system rooted not in individual authorship but in communal knowledge and sacred continuity.

The visual record of these ancient cultures begins in stone—inscribed upon canyon walls and basalt cliffs in the form of petroglyphs. Sites such as Petroglyph National Monument outside Albuquerque and the cliffs of Chaco Canyon present thousands of incised figures: spirals, handprints, animals, solar diagrams, and anthropomorphic shapes. These images are not casual markings but symbols embedded in ritual systems, their precise meanings often opaque to modern viewers but unmistakably intentional. Some are aligned with celestial events—the solstices and equinoxes—while others likely mark migrations, clan symbols, or mythic narratives. The act of engraving stone was itself a declaration of presence and memory, a visual continuity between earth and sky, past and future.

Parallel to this graphic tradition is the architectural grandeur of sites such as Chaco Canyon (900–1150 AD) and Mesa Verde (600–1300 AD). These were not isolated dwellings but vast ceremonial and urban complexes—constructed with remarkable precision from sandstone blocks and timber. The great houses of Chaco, such as Pueblo Bonito, exhibit a mathematical sophistication: aligned to lunar cycles, cardinal directions, and solstitial light. Architecture in this context was not simply shelter but cosmic inscription—where the built environment mirrored and facilitated ceremonial life. Kivas, the subterranean ritual chambers that punctuate these complexes, embodied the Puebloan cosmological axis: a symbolic return to the underworld of origin and a space of regeneration through performance, storytelling, and communal ritual.

Ceramic traditions developed alongside these monumental undertakings, and remain among the most vital threads of continuity in Pueblo art. Early Mimbres pottery (circa 1000–1150 AD), for instance, reveals a stark, refined aesthetic: black-on-white vessels painted with labyrinthine geometry, stylized animals, and enigmatic human figures. The formal clarity of these designs—their rhythmic repetition, symmetrical balance, and minimal color palette—anticipates modernist abstraction by nearly a millennium. Yet their function was not merely aesthetic. Many Mimbres bowls were ritually “killed”—pierced at the center before burial with the dead—suggesting a worldview in which the image served as both container and conduit between realms.

What defines ancient Puebloan art above all is its integration into life: it is not separated from function, belief, or ecological awareness. Weaving, for instance, was both practical and symbolic; pigments derived from mineral and plant sources had not just visual qualities but cosmological resonance. Even body adornment—turquoise jewelry, feathered regalia, shell inlays—operated within a sacred system of balance and identity. Every object was a locus of relationship: with the land, with the ancestors, with the gods.

This is not to suggest stasis. Pueblo cultures, while deeply traditional, were never inert. Archaeological evidence shows trade networks extending to Mesoamerica, the Great Plains, and the Pacific Coast. Parrot feathers, copper bells, cacao, and marine shells have been excavated at inland sites—evidence of a cosmopolitanism born not of empire but of spiritual and material curiosity. Aesthetic forms changed accordingly. Over centuries, pottery styles evolved from Mimbres monochromes to the polychromes of later Rio Grande pueblos. Architecture adapted to new environmental pressures and social configurations, especially after the so-called Great Drought of the late 13th century triggered widespread migrations.

What remains constant, however, is the Pueblo commitment to a cosmological aesthetics: art not as display but as mediation. This is perhaps most evident in the survival of the kachina tradition, which, though reshaped by later events, reaches back to ancient concepts of spirit intermediaries and agricultural harmony. While the formal carving of kachina figures would emerge prominently in the post-contact period, the idea of embodying sacred forces through visual and performative means was long established. In this way, ancient Pueblo art laid the metaphysical groundwork for centuries of resilient artistic expression.

Modern scholars and collectors have often approached this corpus through the lens of “primitive” art or archaeological curiosity, stripping it of its ritual function and recontextualizing it as aesthetic object. This displacement—from shrine or household to museum pedestal—has occluded as much as it has revealed. Only by understanding the original embeddedness of these works can we begin to grasp their full significance. They are not isolated “masterpieces,” but parts of larger systems of meaning, always relational, always ritualized.

In the Pueblo worldview, beauty (hozhó among the Diné, for instance) is not subjective embellishment but moral harmony. To create beautifully is to align oneself with the order of the universe. Ancient New Mexican art, in this sense, was a discipline of balance—between color and form, between self and society, between earth and cosmos.

This foundation, both literal and symbolic, would later be overlaid with foreign forms and violent disruptions. Yet it would not be erased. As we shall see, the arrival of Spanish colonization introduced new aesthetic paradigms, but it also provoked new modes of adaptation, resistance, and synthesis. The art of New Mexico would never be singular again—but the Puebloan foundation would continue to speak, subtly or overtly, through every successive layer.

Colonial Interventions: Spanish Religious Art and Mission Aesthetics

The arrival of Spanish forces in the late 16th century introduced a profound rupture in the visual culture of New Mexico. With the entrada of Juan de Oñate in 1598, a territory previously sustained by indigenous cosmologies and reciprocal relationships with the land was forcibly absorbed into the expanding Catholic empire of Spain. Alongside the sword came the cross, and with the cross, a flood of iconographic and architectural forms whose origins lay in medieval Europe, Iberian Baroque exuberance, and the didactic imperatives of the Counter-Reformation. The mission complex—church, convento, plaza—became the central node of colonial life, both physically and ideologically. In this newly imposed order, art was not peripheral but instrumental: a means of conversion, indoctrination, and visual control.

To understand colonial art in New Mexico, one must first grasp the logic of the Spanish missionary project. The Franciscan friars who spearheaded religious colonization were not simply priests but cultural engineers. Tasked with the salvation of indigenous souls, they saw in European religious art an indispensable tool for conveying Christian doctrine to non-literate populations. The images they brought—whether printed engravings from Seville, small portable sculptures, or locally produced devotional paintings—were vehicles of instruction and persuasion. Saints, martyrs, angels, and biblical scenes were carefully curated to elicit reverence, fear, and ultimately submission to a new theological worldview.

At the heart of this aesthetic mission was the adobe church: a hybrid structure fusing European typologies with local materials and labor. San Miguel Chapel in Santa Fe, often cited as the oldest church in the continental United States, stands as a prototype. Its thick earthen walls, wooden vigas, and subdued façade speak more to indigenous building traditions than to the stone cathedrals of Spain. Yet within, the iconographic program would have been unmistakably European. Altarpieces depicting Christ’s Passion, Marian devotions, and the miraculous lives of saints created a theatrical environment of sacred drama—an immersive space where salvation and damnation were not abstract ideas but visible realities.

These churches were not merely importers of European art; they were also sites of creolization. Over time, a class of local artists—often mestizo or indigenous—emerged to fill the growing demand for devotional images. The santero tradition was born from this crucible. These artisan-devotees carved wooden santos (images of saints), painted retablos (small devotional panels), and constructed reredos (altar screens), combining Catholic iconography with regional aesthetics. Their work, often anonymous, retains a directness and intensity absent from courtly European models. Figures are frontal, their proportions idiosyncratic, their faces solemn or ecstatic. Paint is applied in flat planes, halos gleam with tin or gold leaf, and hands reach outward in blessing or agony. These were not objects of aesthetic contemplation but tools of spiritual intercession.

Santeros such as José Rafael Aragón and José Benito Ortega, active in the 18th and 19th centuries, exemplify the devotional integrity and formal inventiveness of the tradition. Aragón’s work, concentrated in the area around Santa Cruz, is marked by delicate lines, luminous coloring, and an almost Byzantine austerity. Ortega, working later in the southern regions of the territory, brought a more sculptural, baroque intensity to his carvings. Yet both shared a commitment to the religious function of their art—made not for collectors, but for village chapels, household altars, and roadside shrines.

The aesthetics of colonial New Mexico were deeply influenced by the limitations and particularities of place. Materials were scarce: pigments were derived from local minerals, brushes from animal hair, panels from hand-sawn pine. Yet this constraint fostered innovation. Tin was repurposed into nichos (small decorative altars), candle holders, and frames, often adorned with punchwork and engraving. Clay from nearby riverbeds became the basis for devotional pottery, sometimes painted with Christian scenes by artists who retained pre-contact stylistic conventions. Even embroidery and weaving—long-standing Hispano and Pueblo traditions—were incorporated into liturgical vestments and altar cloths.

It would be mistaken, however, to see the colonial aesthetic order as purely imposed or passively received. Indigenous communities adapted to the new regime in complex ways. In some cases, conversion was resisted outright, most famously in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when the indigenous peoples of the region expelled the Spanish for over a decade and systematically dismantled mission churches, burning images and relics in a purgation of spiritual and political subjugation. Yet in the post-reconquest period (1692 onward), a more intricate entanglement emerged. Some pueblos accepted Christianity while subtly preserving ancestral ritual beneath its surface. Kiva ceremonies and Catholic feast days were often scheduled in tandem, their symbolic languages coexisting in uneasy symbiosis.

This syncretism extended to the visual realm. In certain pueblos, one finds santos whose features or dress evoke indigenous rather than Iberian physiognomy. Motifs traditionally reserved for kachinas or other pre-Christian spirits appear subtly integrated into church murals or altar decorations. Even the organization of space within some mission complexes suggests a compromise: sacred geography adapted to accommodate both Christian liturgy and ancestral cosmologies.

The art of this period thus occupies a liminal zone. It is neither fully Spanish nor purely indigenous, but something forged in the crucible of conquest and survival. Its emotional register ranges from the ecstatic to the mournful. It speaks in a visual language of suffering, redemption, awe, and endurance. And it inaugurates a distinctly New Mexican aesthetic: one grounded in sacred narrative, local materiality, and hybrid form.

In this way, colonial religious art established visual conventions that would echo across the centuries. The centrality of the icon, the veneration of the saint, the interplay between vernacular form and spiritual function—all would persist, albeit in transformed guises, through the territorial and modernist periods to come. But already, in the flickering candlelight of an 18th-century adobe chapel, the art of New Mexico had declared its singular character: rooted, resilient, and always in negotiation with forces both divine and imperial.

Casta, Canvas, and Control: Art and Identity in Colonial New Mexico

While the religious art of colonial New Mexico has long attracted attention for its devotional intensity and folk stylization, it operated within a larger matrix of visual strategies deployed by the Spanish empire to maintain order, assert hierarchy, and delineate identity in its far-flung northern territories. The art of this period was not merely concerned with salvation; it was also a subtle but potent vehicle of social control. The aesthetic order reflected—and reinforced—the political order. Through canvas and sculpture, through architectural hierarchy and dress, visual culture became a means of organizing the colonial world, classifying its inhabitants, and legitimizing Spanish dominion over a culturally complex land.

In New Mexico, as throughout New Spain, colonial governance hinged on an elaborate caste system, known as the casta hierarchy. This taxonomy categorized individuals according to their degree of Spanish, indigenous, and African ancestry, with Spaniards born in Europe (peninsulares) occupying the highest rungs, followed by criollos (Spaniards born in the Americas), mestizos, mulattos, and a range of further hybrid identities, each assigned its presumed moral and civic worth. Though primarily a legal and social construct, the casta system found powerful expression in the visual realm.

The most elaborate form of this expression came in the form of casta paintings—genre scenes, often composed in sets of sixteen, depicting families of mixed ancestry alongside inscriptions labeling their racial mixture and societal value. Though these paintings were rare in New Mexico proper (more commonly produced in Mexico City for colonial elites), their underlying logic was deeply present in the visual culture of the northern frontier. Portraits, costume, and domestic ornament all bore coded references to status. Art became a means of both asserting and challenging identity in a world where appearance often determined privilege.

Within the mission system, this logic filtered into every aspect of representation. While the Franciscan project emphasized the universality of Christian salvation, it nonetheless positioned European models as normative. Saints were rendered with Iberian physiognomy; angels wore Romanesque armor or Spanish courtly dress; even the Virgin Mary was often painted in the likeness of Castilian nobility. These iconographic choices were not neutral. They placed the indigenous viewer in a position of perpetual aspiration—salvation was available, but it required transformation, submission, and mimicry. The image became a tool of acculturation, subtly enforcing the erasure of native aesthetics and social forms.

Yet the image also became a space of negotiation. As the 18th century progressed and local santeros came to dominate the production of religious art, a shift in style and representation occurred. Figures became darker-skinned, their dress simplified, their features less Europeanized. Some images, particularly in more remote regions, exhibit figures with traits suggestive of indigenous physiognomy: broad noses, almond-shaped eyes, flattened perspectives. These were not acts of subversion in the modern sense, but rather adaptations—ways of localizing the sacred and re-inscribing presence within a system designed to marginalize.

Architecture, too, served as a visible index of social order. The spatial hierarchy of the mission complex reflected the colonial vision: the church as the axis mundi, elevated and central; the priest’s quarters substantial and well-fortified; the indigenous quarters peripheral and humble. The very layout of space conveyed a message of subordination and control. Yet even within this spatial regime, local artisans inserted forms of resistance or reinterpretation. Carved wooden corbels featured stylized vegetal motifs resonant with pre-contact symbolism. Adobe ornamentation, ostensibly European in function, often bore patterns or arrangements foreign to the Spanish canon.

Clothing and body ornament also played a vital role in visual identity. Spanish authorities attempted to impose regulations on indigenous dress, mandating European styles in certain contexts. But Pueblo and Hispano communities often maintained distinct sartorial languages. Jewelry—particularly turquoise inlay, shell pendants, and silverwork—functioned as both cultural assertion and economic capital. Portraits from later in the colonial period, though rare, sometimes depict subjects adorned with a fusion of Spanish and indigenous elements, reflecting the lived reality of cultural blending in ways that official ideology attempted to suppress.

Even in portraiture, where European conventions of individuality and likeness prevailed, we find fissures. The few surviving colonial portraits from New Mexico—often of clergy or prominent landowners—display a tension between imported ideals and provincial execution. The sitters are often depicted with austere dignity, framed against dark backgrounds, their hands resting on books or rosaries. Yet the rendering is frequently marked by a certain flatness or regional stylization that betrays the hand of a local artist. In these images, the aspiration to European norms is visible, but so too is the reality of distance, improvisation, and adaptation.

Moreover, the boundaries between sacred and secular art were never absolute. Devotional images hung in homes, but so did portraits of ancestors or civic officials. Churches bore not only biblical narratives but also heraldic crests, symbols of royal authority, and votive offerings commemorating local events. The visual culture of colonial New Mexico was saturated with layers of meaning—spiritual, social, political—each interwoven and mutually reinforcing. In this sense, art functioned not just as reflection but as enactment of colonial order.

It is essential to recognize that the visual system imposed by the Spanish was not monolithic. It was challenged from within by the contradictions of colonial life, by the persistence of indigenous cosmologies, and by the very conditions of remoteness and scarcity that characterized New Mexico. The northern frontier was far from the aesthetic centers of Mexico City or Seville. Its artists were self-taught or locally trained; its materials humble; its audiences rural and multilingual. These factors produced a hybrid aesthetic—a vernacular colonialism—that was at once devout and improvisational, hierarchical and porous.

In the decades following the Bourbon Reforms of the late 18th century, which sought to centralize and rationalize the administration of the Spanish empire, even greater attention was paid to visual order. Yet in New Mexico, the distance from imperial centers ensured that the aesthetic regime remained flexible, local, and uniquely expressive. Here, amid adobe walls and mountain passes, the art of colonial control took on strange, often beautiful, and sometimes contradictory forms.

As we turn to the 19th century, we will see how the collapse of Spanish rule and the incorporation of New Mexico into first the Mexican Republic and then the United States reshaped this visual order. But the patterns established under Spanish colonialism—of classification, aspiration, and resistance—would continue to echo, reinterpreted through the new forms of folk art, romanticism, and eventually, modernist longing for the “authentic” Southwest.

Folk Continuities: Santeros, Tinwork, and Weaving in the 19th Century

The 19th century was a period of seismic political transformation in New Mexico, yet its aesthetic life moved along older rhythms, sustained not by courts or academies but by village artisans, oral tradition, and devotional necessity. When Spanish colonial rule ended in 1821 and New Mexico became part of the newly independent Mexican Republic, there was little immediate change in artistic practice. The visual culture of the region had long been shaped more by geography, materials, and faith than by the edicts of distant capitals. What occurred in the 19th century, especially after the American annexation in 1846, was not the disappearance of earlier traditions but their intensification and diversification under new conditions. Folk art, far from retreating, became the principal mode of visual expression, adapting inherited forms to shifting political, economic, and cultural realities.

At the heart of this continuity stood the santero, the devotional artist whose humble materials and sacred intentions shaped the visual landscape of rural New Mexico. Though the term itself derives from Spanish—santo meaning saint—it came to designate a distinct regional practice of religious image-making, rooted in the hybrid traditions of the colonial period but now increasingly autonomous. The santero worked not in ateliers but in home workshops, not for wealthy patrons but for neighbors and churches scattered across the high desert. His tools were few: local wood (typically cottonwood or pine), gesso made from gypsum and glue, pigments from minerals or plants, and, crucially, an intimate knowledge of Catholic iconography adapted to local needs.

The typical output of the santero was the bulto—a carved wooden figure of a saint, apostle, or divine figure—along with retablos, flat devotional panels painted in tempera or watercolor on wood. These images were not judged by academic standards of realism or anatomical correctness; their power lay in their presence, their legibility, their emotional and spiritual resonance. Eyes are often oversized, gazes direct, gestures stylized into open palms or downward glances of humility. The saints appear neither idealized nor grotesque, but utterly human, capable of being approached, petitioned, even argued with. These were not passive images but active participants in the religious and emotional life of the community.

In the post-independence era, and especially after American conquest, this art acquired new layers of meaning. With the collapse of state-sponsored ecclesiastical patronage, local communities became the primary stewards of religious imagery. The santero’s role expanded beyond the liturgical to include the preservation of memory, the assertion of cultural continuity, and the subtle defiance of Anglo-Protestant encroachment. Figures such as José Rafael Aragón (active 1820s–1850s) and José Dolores López of Cordova carried forward the carving traditions into a new era, producing works that remained deeply traditional while subtly responding to new materials and influences.

One of the most notable material adaptations of the 19th century was the rise of tinwork. Tin, a relatively cheap and malleable metal, became widely available through trade with American merchants traveling along the Santa Fe Trail. Discarded tin cans, sheet metal, and other byproducts were collected and repurposed by local artisans into decorative and devotional objects: nichos, small architectural shrines; mirror frames adorned with stamped patterns; candle holders, crosses, and lanterns. Though lacking the monumental scale of church retablos, these tinworks were often marked by remarkable ingenuity and aesthetic refinement. Punchwork techniques created intricate lace-like patterns; colored glass and mica were inserted to enhance reflectivity and color.

Tinwork occupies a peculiar place in the art historical record: simultaneously humble and highly expressive, decorative and sacred. It reveals the adaptive genius of a people who, deprived of traditional resources, invented a new visual vocabulary from the detritus of trade. In so doing, they not only preserved their religious traditions but infused them with a new material and symbolic economy. The shine of tin, unlike the gilded splendor of European altars, was provisional, mortal, and immediate. It reflected candlelight, but also the resourcefulness of a community for whom the sacred was inseparable from daily labor.

Weaving, too, underwent a significant transformation in the 19th century. Long practiced by Pueblo communities and Hispano settlers alike, textile arts became one of the most visible and commercially viable expressions of regional identity. The famed Chimayó weaving tradition, centered in the villages north of Santa Fe, emerged in this period as a distinctive style marked by geometric symmetry, natural dyes, and complex border motifs. Chimayó blankets and rugs—woven on treadle looms and often incorporating Rio Grande patterns inherited from colonial precedents—became both functional items and carriers of cultural meaning. They signified not just craftsmanship, but place, memory, and heritage.

Many Chimayó weavers were men, particularly from families who had inherited the practice across generations. Their work, though commodified over time for tourist markets, originated in a deeply communal system of exchange and apprenticeship. Patterns were not invented ex nihilo, but drawn from inherited repertoires, modified gradually through individual interpretation. The weaver, like the santero, functioned within a matrix of tradition rather than innovation for its own sake. In this, New Mexican folk art stood apart from the industrializing and individualizing trends of 19th-century American art.

By the end of the 19th century, New Mexico had become a U.S. Territory, its landscapes romanticized by Anglo artists and its cultural traditions selectively commodified for burgeoning tourism. Yet within villages and homes, the older forms endured. Devotional art continued to be made, not for galleries but for altars. Tin objects adorned household shrines. Weavings were exchanged, gifted, used, and worn. These objects remind us that the survival of tradition is never a passive act. It requires labor, transmission, and reinvention. In the absence of institutions, these artists created networks of meaning sustained by faith, kinship, and an unbroken commitment to beauty as necessity.

This folk aesthetic, far from being peripheral, became foundational to what would later be mythologized as the “authentic” art of New Mexico. Modernist and Anglo artists, arriving in the early 20th century, would seek inspiration—often unacknowledged or romanticized—in these traditions. But for the communities that made them, these works were never quaint survivals. They were and remain expressions of rootedness, devotion, and continuity.

The Territorial Period: New Myths and Old Materials

The designation of New Mexico as a U.S. Territory in 1850 marked the beginning of a long and uneasy integration into the American national fabric. This political transition, accelerated by the end of the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, was not simply a matter of borders or governance—it was a profound reordering of cultural symbols, spatial imaginaries, and aesthetic priorities. Art, as ever, both recorded and shaped these changes. In the late 19th century, a distinct visual culture emerged in response to the competing pressures of preservation and reinvention, nostalgia and modernization. The Territorial Period (1850–1912) thus became a crucible in which older Hispano and Pueblo forms were selectively recontextualized, while new Anglo-American visual idioms were laid atop them, often in the guise of authenticity.

Central to this reordering was the development of the “Santa Fe Style”—not initially a self-conscious artistic movement, but rather a confluence of architectural, decorative, and pictorial modes that synthesized Pueblo, Spanish colonial, and Anglo-American influences. Its most visible expression was architectural. As the American administration sought to standardize and develop the region, it faced a dilemma: how to integrate New Mexico into the Union without erasing its perceived cultural distinctiveness, which had quickly become a point of fascination for Eastern elites. The solution, paradoxically, was to invent a “traditional” style that was both rooted in the past and legible to modern tastes.

The result was an architectural revival, spearheaded in the early 20th century but gestating already in the Territorial era. Structures such as the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe—originally a 17th-century Spanish edifice—were renovated to emphasize their “adobe” character, their rough-hewn vigas, earth-toned stucco, and courtyard-centered design. Territorial Style architecture, a hybrid typology, fused Greek Revival symmetry with adobe construction, resulting in buildings that bore pedimented windows and brick coping but retained the massing and materiality of the region. These choices were more than aesthetic; they expressed a desire to claim continuity with the land while marking a new political order. The Anglo architects and bureaucrats who promoted this style often framed it as a tribute to native and Hispanic traditions, though it inevitably involved erasure, simplification, and stylization.

Visual art followed a similar trajectory. The late 19th century saw the arrival of surveyors, illustrators, and photographers—figures whose task was not only to map territory but to define its visual identity for an American audience. Painters such as Henry Cheever Pratt, who accompanied U.S. Army expeditions, produced panoramic landscapes and ethnographic portraits that merged scientific observation with Romantic ideals. These works played a dual role: they documented Pueblo villages, Catholic missions, and desert plateaus with impressive fidelity, but they also situated them within a visual narrative of manifest destiny, in which the “ancient” and the “picturesque” were made legible as part of a larger national story.

This process culminated in the emerging tourism and promotional campaigns of the late 19th century. Railroads, particularly the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, commissioned artists and designers to produce brochures, posters, and illustrations depicting New Mexico as a timeless land of adobe churches, indigenous dances, and majestic mesas. The art of the Territory thus became deeply implicated in the construction of myth: a Southwest unchanging, spiritual, and visually distinctive—a place where the modern American could encounter the primitive without real threat.

Yet this myth-making was not unopposed, nor was it always cynical. Local artisans and religious communities continued to produce devotional and vernacular works outside the circuits of commodification. Santero workshops remained active in the Rio Grande Valley, producing images for village processions and home altars. Weavers in Chimayó and beyond adapted traditional patterns for broader markets while retaining older forms of dyeing and loom construction. Pueblo potters—especially at Acoma, Zuni, and San Ildefonso—continued to refine their ceramic traditions, often innovating in form and decoration while maintaining cultural and ceremonial integrity.

These practices were not immune to the pressures of change. The commodification of folk art, accelerated by exposure to Anglo markets, led to aesthetic shifts. Pottery became more finely painted, sometimes larger in scale; santeros experimented with color palettes and new wood sources. In some cases, production shifted from communal to individual focus, as artisans signed their work and oriented it toward outsider collectors. Still, much of this period’s art retained its embeddedness in ritual and locality.

Meanwhile, photography introduced a new visual logic. Figures like Ben Wittick and Edward S. Curtis documented Native and Hispanic communities with technical precision but aestheticized framing. Their photographs—carefully posed, lit, and often staged—circulated in albums and magazines, reinforcing stereotypes of noble simplicity or tragic decline. The Pueblo and Navajo subjects of these images were seldom accorded agency, and yet the photographs remain haunting records, capturing faces and environments now lost or transformed. The camera, like the brush, was a tool of both revelation and control.

In this complex environment, the visual culture of Territorial New Mexico was both deeply conservative and subtly experimental. It drew heavily on inherited forms but adapted them in response to new audiences, new materials, and new expectations. What emerged was a vernacular modernity: a way of negotiating identity, continuity, and representation without severing ties to the past.

The culmination of this period came with New Mexico’s admission to the Union in 1912. By then, the region’s visual identity had been codified into a series of tropes: adobe, saint, pot, dancer, desert. These would be reworked, abstracted, and contested by the modernists who followed. But the Territorial Period remains a pivotal chapter—not a mere bridge between colonial and modern eras, but a moment in which myth was consciously constructed, tradition was selectively preserved, and new materials were invested with the burden of old meanings.

Taos and the Anglo Imaginary: The Rise of a Mythic Southwest

At the turn of the 20th century, the New Mexico landscape—once considered remote, even hostile—underwent a startling transformation in the American cultural imagination. No longer a periphery of empire or a distant frontier, it began to be seen by artists, writers, and cultural elites as a sacred zone of authenticity, a place where premodern values and spiritual clarity had been preserved in visual form. Nowhere was this transformation more concentrated or more emblematic than in the small town of Taos, nestled in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where a community of Anglo-American artists converged to craft one of the most enduring myths in the history of American art: the myth of the Southwest.

Taos, with its ancient pueblo, Catholic mission, and dramatic light, offered to these artists an image of timelessness—a living link to a lost past. This allure was neither accidental nor wholly organic. It was constructed with intent, cultivated through painting, photography, literature, and, later, institutional support. From the very beginning, the Taos art colony was fueled by a dual impulse: reverence and appropriation. Its members admired the Pueblo Indians and Hispanic villagers for their perceived closeness to tradition, yet they rendered these subjects in ways that reflected not the realities of local life but the longings of a disenchanted modern world.

The origins of the Taos colony lie with two artists from the East—Ernest L. Blumenschein and Bert Geer Phillips—who in 1898, en route to Mexico, found themselves stranded in Taos after a wagon wheel broke. Struck by the clarity of the air and the visual drama of the place, they decided to stay. Within a few years, they were joined by Joseph Henry Sharp, Oscar E. Berninghaus, E. Irving Couse, and others. In 1915, this group formally organized as the Taos Society of Artists, an exhibition cooperative intended to bring their work to audiences in New York, Chicago, and beyond. Their stated mission was to paint “the Southwest and its peoples” in a way that would preserve what they believed was vanishing under the pressures of assimilation and modernization.

This notion of the “vanishing” Native—romanticized, elegiac, noble—was central to the colony’s visual project. Pueblo subjects were rendered with great attention to dress, ritual, and physical detail, yet placed within compositions that abstracted them from contemporary reality. In the paintings of E. Irving Couse, for instance, Native men are shown in solemn repose, often beside fires or in the act of performing spiritual tasks, their faces impassive, their surroundings spare and symbolic. The works exude a respectful stillness, but it is a stillness that freezes its subjects in an idealized past.

Likewise, the work of Blumenschein and Sharp often emphasized ethnographic fidelity over psychological depth. Pueblo dancers, weavers, and potters are presented not as individuals but as types—icons of cultural continuity. Costumes are meticulously painted, but interiority is withheld. The artists did not seek to depict their subjects in modern dress or in moments of everyday life; rather, they captured what they saw as the ceremonial essence of a people untouched by time.

This approach had consequences. While the Taos painters helped elevate Native and Hispanic imagery to national attention, they also solidified stereotypes that would persist for decades. Their work reinforced the idea that the indigenous cultures of New Mexico were static, spiritual, and premodern—a foil to the alienation of the industrialized world. In this way, the colony functioned as a kind of aesthetic salvage operation, rescuing “authenticity” from modernity by re-inscribing it in oil paint and selling it to urban collectors hungry for meaning.

Yet the story is not so simple. The Taos artists, for all their limitations, were not mere exploiters. Many of them developed close, respectful relationships with their subjects. Some, like Berninghaus, advocated for Pueblo land rights. Others, like Couse, maintained long collaborations with Native models who helped shape the aesthetic vocabulary of the paintings. And there is an undeniable formal beauty to much of this work: an ability to render texture, light, and atmosphere with extraordinary sensitivity. These were artists who believed deeply in the moral and spiritual function of art, and who saw in New Mexico a refuge from the decadence of American consumer culture.

Their influence extended beyond the easel. The Taos colony played a central role in shaping the cultural identity of New Mexico as it approached statehood. Their paintings appeared in state promotional materials, national exhibitions, and eventually in museums such as the Harwood Museum of Art, founded in 1923. Collectors, tourists, and fellow artists flocked to Taos, turning what had been an isolated village into a symbolic capital of Southwestern art.

This influx had ambiguous effects. On one hand, it provided income and visibility for local craftspeople, particularly potters and weavers. On the other, it encouraged the commodification of cultural forms, recasting ritual objects as decorative goods and ceremonies as tourist spectacles. The aesthetic of Taos became a brand, and that brand was marketed with increasing aggressiveness in the decades to follow.

Still, the colony left a legacy that cannot be reduced to commercialism. It helped create a new regionalism—distinct from the nationalism of the Hudson River School or the urban cosmopolitanism of the Ashcan painters—a regionalism that took seriously the idea of place as a source of moral and formal inspiration. The artists of Taos painted not just landscapes but cultural landscapes, where earth, architecture, and people formed an indivisible whole.

By the 1920s and 30s, younger and more experimental artists would challenge the colony’s conventions, embracing abstraction, political engagement, and deeper collaboration with Native artists themselves. But the foundational image of New Mexico in the American imagination—the adobe wall, the bowed dancer, the sacred mountain—was crafted in large part by the painters of Taos. Their work, for all its blind spots, remains a testament to the power of myth, and to the complicated ethics of artistic desire in a land shaped by conquest and endurance.

Modernism in the Desert: O’Keeffe, Marin, and the Arrival of Abstraction

If the Taos painters articulated a vision of New Mexico rooted in ethnographic reverence and romantic figuration, the next generation of artists—many of them drawn not to Taos but to Santa Fe and Abiquiú—sought to break that pictorial stasis. For them, the desert was not merely the backdrop for ritual and timelessness; it was a formal proposition, an invitation to abstract line, radical reduction, and metaphysical inquiry. The arrival of modernism in New Mexico did not merely displace the visual idioms of the earlier Anglo colony. It reoriented the very axis of perception. The mesa was no longer a cultural signifier—it was form, mass, shadow. The skull was no longer a memento of death—it was line, void, and light.

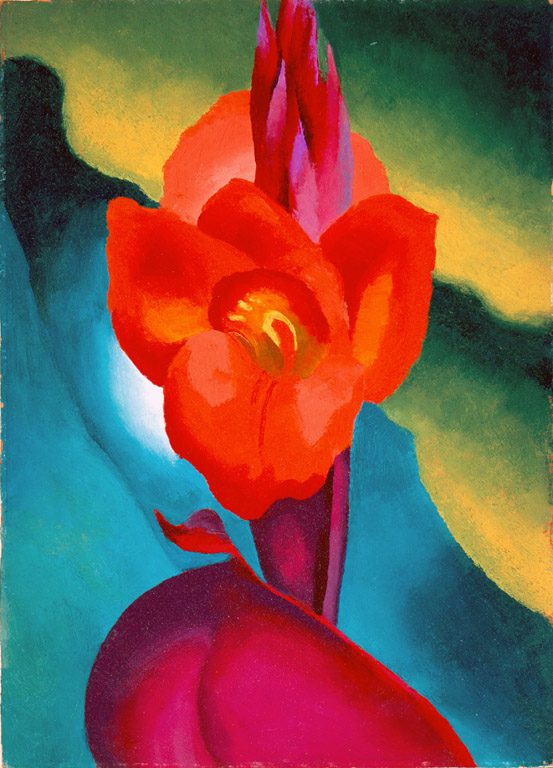

The most emblematic figure in this modernist turn was Georgia O’Keeffe, who, though neither the first nor the most doctrinaire of the modernists in New Mexico, remains its most iconic. O’Keeffe’s journey to the Southwest began in the late 1920s, following years of success in New York under the mentorship and eventual marriage to photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz. Her early abstractions had already marked her as one of the leading figures of American modernism, but it was New Mexico that would crystallize her vision into something both starkly individual and regionally transformative.

Arriving first in Taos in 1929 at the invitation of Mabel Dodge Luhan, O’Keeffe soon rejected the mythologizing aesthetic of the local colony. She was uninterested in painting Pueblo rituals or Hispanic saints. Instead, she turned her gaze toward the land itself—its eroded cliffs, sun-bleached bones, and parched vegetation. These subjects became, in her hands, not symbols of cultural otherness but formal epiphanies. A jawbone was a pure curve; a hill an accumulation of tonal strata. In works like Black Cross, New Mexico (1929) and Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills (1935), she fused representational clarity with compositional abstraction, creating images that floated between presence and emptiness, image and idea.

O’Keeffe’s relationship to New Mexico was intensely personal yet also emblematic of a broader shift in American art. The Southwest, for her and for others, became a site of purification—not in the ethnographic sense favored by the Taos Society, but in the modernist pursuit of elemental form. Her paintings eschewed narrative, folklore, or historicism. They presented the land as visual fact, distilled to its essential shapes. It is telling that she eventually made her home at Ghost Ranch and later in Abiquiú, choosing isolation and landscape over community and institution. Her home, meticulously arranged, became an extension of her aesthetic: austere, monastic, composed.

O’Keeffe was not alone in this desert formalism. John Marin, associated with the Stieglitz circle and among the earliest American abstractionists, visited New Mexico in the 1920s and produced a series of works that translated the land into rhythmic, almost musical, compositions. In Taos Canyon, New Mexico (1929), jagged lines and fractured planes convey not the topographical accuracy of the place but its kinetic energy. For Marin, the desert was not a still tableau but a site of dynamic tension between structure and flux. His approach, though radically different from O’Keeffe’s spatial serenity, shared her modernist aim: to render the landscape not as illustration but as experience.

Other figures followed, less known but equally committed to the region’s formal potential. Marsden Hartley, though less sustained in his presence, painted New Mexico in a more symbolist and expressionist key. His El Santo series and landscape abstractions are charged with emotional compression, locating in the land a kind of metaphysical weight. Raymond Jonson, who would later help found the Transcendental Painting Group, arrived in New Mexico in the 1920s and brought with him a commitment to non-objective spiritual abstraction, seeing the land as a catalyst for inner vision rather than an object of mimesis.

What unites these modernists is not merely style, but a new relation to the Southwest. They did not depict New Mexico as a cultural artifact, nor did they romanticize its people. Rather, they approached it as a site of optical and metaphysical possibility. The land became, in their eyes, a surface on which to test the boundaries of form, color, and sensation. In this, they participated in a broader modernist project: the search for a new visual language suited to a fragmented and accelerating world.

Yet the modernism of New Mexico, for all its radical ambition, remained deeply regional. It did not seek to obliterate place but to extract from it a heightened sense of presence. The sharp edge of a mesa, the opacity of shadow under a bone, the chromatic burn of afternoon light—these were not mere references but visual arguments. The works produced in New Mexico during this period often lack the urban irony of contemporaneous New York modernism. They are slower, more contemplative, and in their own way, more spiritually aspirational.

This pursuit, however, came at a cost. The abstraction of the land sometimes entailed the abstraction of its history. Modernist painters in New Mexico frequently erased or elided the very cultural legacies that made the land legible. The pueblos, missions, and villages that had structured centuries of visual life in the region became backdrops or vanished altogether. The land was purified—but also depopulated. This tension between formal innovation and cultural erasure would become more explicit in later decades, as Native and Hispano artists pushed back against the modernist imaginary.

Still, the impact of O’Keeffe and her peers is undeniable. They redefined what it meant to make art in and of New Mexico. They opened the region to new vocabularies—of reduction, of silence, of luminous intensity. And they left behind a body of work that continues to shape how the Southwest is seen, felt, and rendered in the visual imagination.

The Transcendental Painting Group and the Metaphysics of Form

By the late 1930s, New Mexico had firmly established itself as a site of artistic pilgrimage. Its light, landscape, and symbolic charge continued to draw painters from across the United States and Europe. But while earlier modernists such as O’Keeffe and Marin had used the desert to distill natural forms into abstraction, a new generation of artists sought something more radical: not the formal abstraction of nature, but the visual expression of metaphysical truth. For these artists, New Mexico was not merely a compositional resource but a spiritual threshold—an axis where matter thinned and mind expanded. Their project was not to represent the world, but to transcend it. Out of this aspiration arose the Transcendental Painting Group, one of the most intellectually ambitious and visually singular movements in American art.

Founded in Santa Fe in 1938 by Raymond Jonson and Emil Bisttram, the group articulated a manifesto that went beyond the formal tenets of modernism. They believed that painting could—and should—serve a higher function: to awaken spiritual consciousness, to guide the viewer into realms beyond sensory experience. In their words, they aimed “to carry painting beyond the appearance of the physical world, through new concepts of space, color, light and design, to imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual.” In this vision, art was not an object but a portal, and abstraction was not a stylistic choice but a metaphysical imperative.

The group, which at its height included Jonson, Bisttram, Lawren Harris, Agnes Pelton, Florence Miller Pierce, and others, shared some affinities with earlier spiritual modernists such as Kandinsky and Mondrian. But their context—rooted in the mysticism of the Southwest—lent their work a distinctive texture. New Mexico’s vast sky, its geological stillness, its ceremonial intensity—all fed into a visual grammar of radiance, concentricity, and dissolution. The desert did not inspire figuration, but disembodiment. Its spareness became an analogue for inner space.

Raymond Jonson, who had arrived in New Mexico in 1924 to teach at the University of New Mexico, was the intellectual and aesthetic anchor of the movement. His work evolved from early precisionism to a more fluid and luminous abstraction that often employed bold color bands, ethereal geometries, and rhythmic curvatures. In works such as Oil No. 9 (1939) or Watercolor No. 12 (1940), one sees not an object in space but a pulse of energy, a vibration rendered in pigment. Jonson viewed painting as a form of visual music—an architecture of frequency, governed by harmony and resonance. For him, the canvas was a site of elevation, where the viewer might escape material bondage and approach a purer mode of being.

Emil Bisttram, a Hungarian-born artist who had studied with Diego Rivera and been influenced by Theosophy and Eastern thought, brought a more structural mysticism to the group. His compositions often feature crystalline forms, symbolic color contrasts, and a strong axial balance. Works such as Oversoul (1939) or Approach to Vertical (1940) exemplify his concern with ascension, with upward movement toward transcendence. The titles alone signal a metaphysical lexicon, drawn from mystic Christianity, Platonic idealism, and esoteric philosophy. Bisttram believed that geometric abstraction was not an escape from meaning, but its most refined articulation.

The inclusion of Lawren Harris, a Canadian painter and former member of the Group of Seven, deepened the group’s conceptual foundations. Harris had already made a name for himself with his spiritualized landscapes of the Canadian north, and his move toward pure abstraction found in the Transcendental Painting Group a natural home. His work from this period—such as Abstract Painting No. 20 (1939)—fuses verticality with interior luminosity, echoing both alpine forms and mystical ascent. Harris brought to the group a rigorous spiritualism, one that sought not ecstasy but stillness, not drama but inner clarity.

Perhaps the most haunting and refined voice in the group was Agnes Pelton, whose work unfolded far from Santa Fe in Cathedral City, California, yet whose inclusion in the group speaks to its broader network of spiritual abstractionists. Pelton’s paintings—glowing orbs, floating mandorlas, undulating forms suspended in indigo or pale gold—offer a feminine counterpoint to Jonson’s and Bisttram’s architectural visions. Works like Mount of Flame (1932) or Orbits (1934) radiate an inner light that seems both sacred and erotic, cosmic and intimate. Pelton’s art, like the desert itself, defies binary: it is both veil and revelation.

What unified these artists was not a style but an ethos. They rejected materialism, realism, and the political agitation of social realism (then dominant in Depression-era American art). Instead, they posited art as a meditative act, a visual analog to prayer or contemplation. Their canvases offered no narrative, no referent, but invited the viewer to surrender perception and enter into a realm of pure relation—between line and color, form and void, self and cosmos.

The group’s work was undergirded by a sophisticated theoretical framework. Influenced by Theosophy, Anthroposophy, and various strains of esoteric mysticism, they believed in the unity of art, science, and spirit. Geometry was not neutral—it was sacred; color was not sensation—it was vibration; space was not illusion—it was presence. In their meetings, writings, and exhibitions, they articulated a visual metaphysics that stood apart from the more secular experimentation of their contemporaries in New York or Paris.

Despite the depth of their vision, the group’s existence was brief. By 1941, as the United States entered World War II and public attention shifted toward more overtly political and figurative art, the Transcendental Painting Group disbanded. Their works were marginalized for decades, dismissed by critics as too esoteric, too decorative, or too idealistic. Only recently have they been rediscovered, their significance reassessed not only in the context of American modernism but in the broader history of spiritual abstraction.

New Mexico, for them, was not an aesthetic setting but a metaphysical condition. Its vastness, silence, and sense of geological time offered the ideal space in which to test the limits of form and vision. In this sense, the Transcendental Painting Group represents a high point in the region’s art history—not because they captured New Mexico, but because they used it to access something beyond the visible. Their paintings remain, in the deepest sense, propositions—visions of what art might become when released from the gravity of the world.

Postwar Shifts: Native Artists and the Battle for Aesthetic Sovereignty

In the decades following World War II, a profound transformation began to take shape in the art of New Mexico—not one defined by stylistic evolution alone, but by a recalibration of authorship, audience, and aesthetic legitimacy. While earlier eras had seen indigenous people rendered as subjects, symbols, or motifs within Anglo-American artistic projects, the postwar period witnessed the emergence of Native artists as fully self-conscious agents of aesthetic production—rejecting the roles assigned to them in the romantic and ethnographic imagination and asserting new visual languages grounded in both inheritance and autonomy. It was a decisive shift: from representation to self-representation, from motif to maker, from image to voice.

This transformation did not occur in isolation. It must be situated within a broader landscape of postwar cultural reorientation, in which formal experimentation, political unrest, and changing institutional frameworks altered the possibilities of artistic expression across the United States. In New Mexico, these forces converged with an especially fraught legacy: centuries of visual appropriation, cultural distortion, and paternalistic patronage. The question was not simply whether Native artists would gain access to art markets and museums, but whether they could define the terms of aesthetic value on their own.

One of the key battlegrounds in this struggle was modernism itself. For decades, Native artists had been trained in schools and workshops that emphasized ethnographic fidelity and stylistic conservatism. Institutions such as the Santa Fe Indian School and its influential Studio School, founded in 1932 by Dorothy Dunn, promoted a “flat style” of painting—emphasizing two-dimensional design, muted palettes, and traditional subject matter (dances, ceremonies, animals, mythology). While Dunn believed she was preserving Native traditions, her pedagogical model imposed a visual orthodoxy that reinforced outsider expectations of what “Indian art” should look like: decorative, spiritual, non-confrontational.

By the 1960s, a new generation of Native artists began to chafe against these constraints. Educated in mainstream art schools or influenced by broader cultural upheavals, they sought to challenge both the stylistic boundaries and the political implications of Native art as it had been framed by non-Native institutions. Chief among them was Fritz Scholder (Luiseño), whose explosive work shattered the pieties of Indian painting and redefined what it meant to depict Native life.

Scholder, who taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe beginning in the mid-1960s, brought with him an irreverent, emotionally raw, and visually aggressive style. Rejecting both the romanticism of the Taos painters and the ethnographic delicacy of the Studio School, he painted Native subjects as psychologically complex and historically burdened. His Indian No. 1 (1967) depicts a Native man not in regalia but in an overcoat and sunglasses, cigarette in hand—a jarring figure who confronts the viewer with the artifice of cultural expectation. In Super Indian No. 2, Scholder’s Native subject dons a cape and comic-book stance, mocking both the iconography of American heroism and the sentimentalization of indigenous identity.

These works were not intended to comfort, but to disturb. Scholder deployed expressionist brushwork, acid color, and mordant humor to collapse the aesthetic distance that had long sanitized Native subjects for Anglo consumption. His work announced the end of innocence—both artistic and political. The Indian, in Scholder’s canvases, was no longer an object of reverence or pity, but a fractured figure navigating the grotesque ironies of postcolonial modernity.

Following closely was T.C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo), a student of Scholder’s and one of the most gifted and complex artists to emerge from IAIA. Cannon’s work combined biting social critique with formal sophistication, often juxtaposing traditional motifs with pop cultural imagery. In Two Guns Arikara (1974), a Native figure in a starched suit sits before a decorative backdrop, blending the compositional coolness of Alex Katz with the symbolic density of Kiowa ledger art. Cannon’s colors are bold, his references layered, his tone oscillating between elegy and satire. Through him, Native art entered the arena of irony, ambiguity, and high conceptual stakes.

What Scholder and Cannon pioneered was not simply a new style but a new framework of aesthetic sovereignty. They refused to play the roles assigned to them by either curators or collectors. They redefined authenticity not as fidelity to external expectations, but as the capacity to speak from within contradiction. Their influence reverberated outward, challenging other Native artists—and institutions—to reckon with the inherited violence of cultural display.

At the same time, Native modernism was not monolithic. Other artists pursued quieter, more introspective paths. Helen Hardin (Santa Clara Pueblo), for instance, developed a geometric abstraction rooted in Pueblo symbology and personal spirituality. Her paintings—intricate, mathematically precise, often shimmering with iridescent pigment—invoke both ancestral motifs and futuristic speculation. In works like Changing Woman and Medicine Woman, Hardin fused female divinity, cultural inheritance, and personal agency into compositions of great formal elegance and symbolic force.

The postwar decades also saw a resurgence of interest in traditional media, not as static inheritance but as sites of innovation. Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo), who had begun her revolutionary black-on-black pottery decades earlier, continued to refine her techniques, collaborating with her son Popovi Da to explore new forms, finishes, and symbolic incisions. Their work was both grounded in communal tradition and consciously modern, situating San Ildefonso pottery within the broader discourse of sculptural abstraction.

Meanwhile, institutions slowly began to shift. The founding of the Institute of American Indian Arts in 1962 marked a watershed moment. IAIA offered Native students access to formal training, cross-cultural dialogue, and experimental freedom without the ideological constraints of earlier programs. Its alumni would go on to shape the landscape of Native contemporary art well into the 21st century.

Yet even as Native artists gained visibility, they continued to navigate an art world that commodified their work within tightly policed categories. “Indian art” remained a genre, a market, a museum wing, rather than an equal participant in the broader currents of modernism and contemporary expression. Artists were often expected to be legible, to produce work that could be recognized and marketed as “authentic”—a term whose very invocation implied an audience outside the culture itself.

Against this backdrop, the postwar Native art of New Mexico must be seen not simply as a stylistic evolution, but as a philosophical and political assertion. It claimed space not only on walls but within discourse. It demanded to be seen—not as a picturesque survival, but as a living, thinking, aesthetic force. These artists asked difficult questions: Can there be a Native modernism? What is the cost of visibility? Who controls the narrative of tradition?

Their answers were diverse, often contradictory. But together, they reshaped the visual history of New Mexico—taking the image of the Indian, long manipulated by others, and returning it, with force and ambiguity, to its rightful makers.

Santa Fe’s Art Market: Commodification, Tourism, and Identity Politics

By the latter half of the 20th century, Santa Fe had evolved into one of the most prominent art markets in the United States—remarkable not for its size but for its singular identity. Unlike New York or Los Angeles, whose art worlds are shaped by contemporary cosmopolitanism and the cycles of institutional fashion, Santa Fe’s market is defined by a carefully cultivated regionalism: a visual economy that trades in authenticity, cultural heritage, and the mystique of place. It is an art world built not only on aesthetics, but on myth—sustained by tourism, gentrification, and a persistent appetite for images of the Southwest that confirm rather than challenge expectation. At the center of this phenomenon lies a complex nexus of artists, collectors, galleries, and institutions—each implicated in the commodification of tradition and the negotiation of identity.

The foundation of Santa Fe’s art economy is its transformation, beginning in the early 20th century, from a modest adobe town to a cultural enclave. This process, accelerated by the arrival of artists, writers, and preservationists, was further institutionalized with the establishment of museums and promotional bodies such as the Museum of New Mexico and the New Mexico Association on Indian Affairs. These entities promoted the region as a site of cultural authenticity, where ancient traditions flourished unbroken. Art was central to this narrative—not as autonomous production, but as living heritage.

From the outset, this promotional framework was entangled with commerce. The Santa Fe Indian Market, founded in 1922, exemplifies the double bind that would come to characterize the city’s art scene. On one hand, it created an unprecedented venue for Native artists to showcase and sell their work directly to the public. On the other, it codified expectations—establishing criteria for what counted as “authentic” Native art and marginalizing forms that did not conform to established styles. Artists who experimented with abstraction, political content, or cross-cultural techniques often found themselves excluded from juried exhibitions or dismissed by buyers seeking “traditional” work.

A similar tension shaped the broader art market. Galleries proliferated along Canyon Road, selling a vast array of works—from Pueblo pottery and Navajo textiles to oil paintings of high desert mesas and bronze statues of cowboy heros. Many of these galleries served an affluent tourist clientele, eager to take home a piece of the Southwest’s romantic aura. Paintings featuring sunset-colored cliffs, stoic Native figures, and adobe churches became market staples, satisfying a longing for visual continuity in a fragmented world. But this demand for the picturesque often narrowed the field of acceptable expression. Artists learned quickly that to deviate from the expected Southwest aesthetic—to engage in conceptual art, performance, or visual critique—was to risk commercial marginalization.

The problem was not merely one of taste, but of structural incentive. Santa Fe’s economy came to depend on the commodification of culture. Entire neighborhoods were reshaped to accommodate this trade: adobe façades became mandatory, Pueblo and Territorial styles were imitated and exaggerated, and public art projects often leaned into the folkloric rather than the experimental. Aesthetic choices were guided by market logic. Tradition was not merely preserved—it was curated, stylized, and packaged.

In this context, Native and Hispano artists faced particular challenges. Their work was not viewed on equal footing with Anglo contemporaries producing in the idiom of New York abstraction or international conceptualism. Instead, it was typically categorized as ethnic or folk art, positioned outside the dominant critical frameworks of modernism. Even successful artists often found themselves ghettoized within special exhibitions, heritage festivals, or craft-oriented galleries. The very institutions meant to elevate indigenous art—museums, festivals, and heritage organizations—often reinforced a reductive vision of cultural identity, where form was mistaken for essence and variation for dilution.

At the same time, these dynamics produced a complex ecology of agency, resistance, and negotiation. Many Native artists learned to navigate the market’s expectations while subtly subverting them. Potters, for instance, innovated new forms and glazes while maintaining traditional surface motifs; painters embedded satirical or ironic content within seemingly conventional frames. Some artists embraced the market’s demands as a means of survival and visibility; others rejected it altogether, producing work that circulated outside commercial systems, in ceremonial or communal contexts.

Hispano artists, too, operated within these contradictions. The santero tradition, once a form of anonymous village devotion, became an object of curatorial and collector interest. Santeros began signing their works, experimenting with scale, and entering juried exhibitions. While some purists decried this as the degradation of a sacred art form, others saw it as a necessary adaptation—proof that the tradition was alive and evolving. Still, the pressure to conform to a certain visual vocabulary—austere saints, symmetrical altars, adobe churches—remained ever-present. Works that addressed contemporary issues, political themes, or personal iconography often met with resistance.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a growing number of artists and curators began to challenge these limitations directly. Exhibitions such as Wheelwright Museum’s explorations of Native contemporary art, and independent collectives such as Heard Museum’s experimental programs, sought to expand the definitions of Native and regional art beyond the confines of the marketplace. Meanwhile, artists such as Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo) created ceramic works that fused Pueblo tradition with pop culture, comic satire, and sexual politics—undermining the solemnity expected of Native art. Romero’s pots, decorated with images of superheroes, erotic figures, and cultural mashups, both invoked and exploded the categories imposed by Santa Fe’s art market.

In this new generation, identity politics became both a source of tension and of power. Artists confronted the fact that their ethnicity was often the primary frame through which their work was interpreted. Some resisted this framing; others weaponized it, using cultural signifiers to interrogate the very systems that sought to commodify them. Art became a battleground over who had the right to define tradition, authenticity, and representation.

At the institutional level, change was slow. Major museums and galleries remained largely conservative in their programming. The Santa Fe market continued to valorize the aesthetic of timelessness. Yet beneath this surface, a more dynamic and pluralistic art scene began to emerge: artist-run spaces, interdisciplinary collaborations, and transregional dialogues reshaped the possibilities of expression.

By the early 21st century, Santa Fe’s art world remained a paradox. It offered exposure and income to artists, yet often at the price of conformity. It preserved traditions while freezing them in nostalgic amber. It celebrated diversity, but frequently through a lens of consumption. To participate in this system was to enter a hall of mirrors—where every work was a reflection of expectation, desire, and economic calculation.

And yet, even within these constraints, artists continued to make work of depth, vitality, and formal invention. They reimagined what it meant to be a Native potter, a Hispano santero, an Anglo modernist, a Southwestern painter. They used the market’s infrastructure to disseminate new forms, new voices. They fought to reclaim aesthetic sovereignty—not by rejecting tradition, but by refusing its ossification.

Contemporary Currents: Hybridity, Irony, and Regional Reinvention

In the first decades of the 21st century, New Mexico’s art scene entered a new phase—defined less by adherence to inherited forms than by a restless interrogation of them. While traditional media and motifs remained present, they now coexisted with conceptual installation, digital manipulation, performance, and satire. The artists working in and around Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Taos, and beyond no longer framed themselves as regionalists in the old sense; they were instead engaged in a deliberate reinvention of what “regionalism” could mean—plural, ironic, defiant, and structurally aware. New Mexico, long positioned as a refuge for aesthetic authenticity and cultural timelessness, became a proving ground for contemporary hybridity.

At the core of this transformation is a generational shift. Younger artists—many trained in national or international programs, many returning to their ancestral homelands or drawn anew to the Southwest—approached regional identity not as an essence to be preserved but as a material to be recomposed. They understood that tradition was not monolithic, and that the very tropes of New Mexican art—adobe walls, Native dancers, saintly icons, vast empty landscapes—had been commodified into visual shorthand. Their response was neither rejection nor repetition, but complication: a layered practice in which the visual idioms of the past were cited, scrambled, recontextualized, or ironized.

A striking example of this is found in the work of Cannupa Hanska Luger, a multidisciplinary artist of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, and European ancestry. Luger’s practice—spanning sculpture, video, performance, and social collaboration—foregrounds the fluidity of indigenous identity in the contemporary world. His installations often juxtapose traditional materials (clay, beadwork, bone) with industrial detritus or digital forms, creating works that are at once ceremonial and confrontational. In Every One (2018), Luger collaborated with communities to produce thousands of ceramic beads representing missing and murdered Indigenous women. The result, a monumental curtain of faces, fused craft with activism, collective ritual with conceptual clarity. The work makes clear that contemporary indigeneity is not confined to stylistic markers; it is a living, grieving, resisting force.

This ethos of cross-medium hybridity is shared by artists like Rose B. Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo), whose ceramic figures, performance works, and installations explore posthuman identity, trauma, and survival. Simpson’s large-scale sculptures—often humanoid but stylized and armored—evoke both ancestral power and cybernetic ambiguity. They resist easy legibility, challenging the viewer to navigate their affective and cultural charge. In pieces such as Ground or Genesis, one finds echoes of Pueblo cosmology, sci-fi aesthetics, and feminist corporeality fused into singular forms.

Hispano artists, too, have engaged in reinvention. The santero tradition has not vanished but mutated, finding new contexts and purposes. Artists such as Nicholas Herrera, known as the “El Rito Santero,” combine devotional imagery with social commentary, satire, and autobiographical reference. Herrera’s painted and sculpted works often include elements of Chicano culture, border politics, gang iconography, and environmental crisis. His Death of a Gangbanger or San Isidro with Chainsaw collapse the distance between saint and citizen, icon and agitprop. These are not nostalgic works but confrontational hybrids—part folk art, part political cartoon, part sacred theater.

This irony-laced regionalism also animates the work of Diego Romero, whose ceramic vessels update the Pueblo storytelling tradition with a subversive twist. Romero’s pots, wheel-thrown and decorated in fine-line technique, often depict muscular Native superheroes, erotic vignettes, or scenes of cultural satire—punning on classical Greek pottery while addressing the absurdities and violences of modern American life. His series Chongo Brothers imagines Native men as comic-book protagonists, navigating love, war, and cultural survival with bravado and wit. In Romero’s work, Pueblo identity becomes something mobile, stylized, carnivalesque—retaining its roots while shedding imposed solemnity.

Meanwhile, a broader community of artists across the state has embraced interdisciplinary experimentation, challenging the formal and spatial conventions of New Mexico’s art institutions. Performance artists such as Raven Chacon (Navajo) blend sound art, experimental music, and installation to interrogate systems of power, surveillance, and land control. In Still Life No. 3, Chacon stages a composition in which sound becomes a spatial disruption, echoing across topographies with political resonance. His work refuses to be bounded by visuality alone; it is an ambient, immersive critique of the structures that govern presence and erasure.

Similarly, collectives such as Postcommodity, co-founded by Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist, deploy multimedia strategies to subvert institutional narratives. Their 2015 installation Repellent Fence stretched a series of giant balloon spheres across the U.S.-Mexico border, referencing both indigenous visual markers and surveillance aesthetics. It was both absurd and solemn, a temporary monument to transborder continuity in an age of increasing division. Postcommodity’s interventions resist easy consumption—they are acts of cultural hacking, redirecting the logic of spectacle toward moments of destabilization.

Outside the walls of galleries, new art spaces and residencies have begun to shift the infrastructure of cultural production. Organizations such as SITE Santa Fe and 516 ARTS in Albuquerque offer platforms for contemporary artists working across media and identity positions. Their exhibitions increasingly highlight works that interrogate environmental precarity, colonial legacies, and cross-cultural hybridization—pushing back against the decorative inertia of the commercial art market.