The story of New Hampshire’s art begins not in studios or galleries, but in farmhouses, meetinghouses, and workshops scattered across a rugged landscape of forest and granite. Before there were painters or sculptors recognized by name, there were anonymous hands shaping wood into tools, carving signs for taverns, or stitching patterns into quilts that gave warmth as well as beauty. In these earliest centuries, art in New Hampshire was never separate from survival, devotion, or community identity. What might appear at first as plain or unadorned objects often carried a surprising intensity of craftsmanship, meaning, and ingenuity.

Colonial craft and daily necessity

The first European settlers who arrived in the 17th century brought with them practical skills forged in England’s villages and towns: carpentry, joinery, weaving, and ironwork. These were not luxuries but necessities for building a life in a challenging new environment. Yet necessity did not prevent artistry. A chest made to hold clothes was also an opportunity to cut decorative panels; a meetinghouse pulpit, though meant for sermons, could be shaped with subtle curves and moldings that revealed a maker’s eye for proportion.

One of the most enduring traditions was woodworking. The abundance of local timber allowed settlers to craft sturdy furniture—tables, chairs, and cupboards—that often echoed Old World forms while gradually developing regional variations. These pieces, though rarely signed, displayed a sense of harmony between form and function that would remain a hallmark of New Hampshire’s craft traditions. In the Seacoast towns, where trade flowed in and out of Portsmouth, imported goods mingled with local production, bringing influences from Boston and beyond. In the interior, self-reliance meant that homespun textiles and hand-carved utensils carried an unmistakably local character.

The daily tools of life—sleds, butter churns, looms—were also shaped with an eye for proportion and rhythm. To modern eyes, the combination of practical necessity and understated embellishment offers an early glimpse of what might be called an aesthetic of plainness, where beauty was not ornament for its own sake but the natural byproduct of careful, competent making.

Folk art in rural towns

As communities stabilized in the 18th century, visual expression began to move beyond utility into symbolic and decorative realms. Rural households decorated walls with stencil patterns or painted panels, often passed from neighbor to neighbor by itinerant craftsmen. The simple boldness of these designs carried both individuality and shared community taste.

Tavern signs were among the first public art forms to appear in towns across New Hampshire. Painted with eagles, ships, or fantastical animals, they advertised establishments while also serving as landmarks in a time when literacy was not universal. Their bold outlines and vibrant colors made them both practical and striking, and some of the finest examples survive in regional collections today.

Another vital channel for visual expression was gravestone carving. In village cemeteries from Portsmouth to Keene, early carvers left behind a gallery of winged skulls, cherubs, and urns. Each stone was not only a memorial but a small artwork, blending theology with folk imagination. The imagery reflected both stern Puritan beliefs and a gradual softening toward sentimental remembrance as the 18th century unfolded. These stones remain among the most enduring records of early artistic life in New Hampshire—works of anonymous sculptors whose chisels cut enduring designs into local slate and granite.

By the turn of the 19th century, folk portraiture began to emerge. Farmers, mill owners, and merchants sometimes commissioned likenesses from itinerant artists who traveled town to town. These portraits often appear stiff and flat by academic standards, but they captured with honesty and charm the sitters’ clothing, household goods, and even the gleam of a pewter teapot. Each painting preserved the identity of families who might otherwise have disappeared into records of land deeds and wills.

- A tavern sign painted with a giant gilt lion could dominate the center of a town square.

- A gravestone carved with a winged death’s head warned of mortality with stark imagery.

- A simple stencil border in a farmhouse parlor transformed a plain white wall into pattern and rhythm.

Such works did not aim at fame or refinement but at continuity—linking one generation to the next, marking place and identity in a new land.

Religious and symbolic motifs

Religion was central to early community life, and it inevitably shaped visual expression. Meetinghouses, though plain compared with European churches, were built with proportions that carried symbolic weight. A pulpit raised high above the congregation reflected theological priorities, while tall, narrow windows brought light that could seem almost spiritual in effect.

Decorative motifs often carried Biblical or moral meaning. Painted panels might include trees, suns, or stars with resonances of scriptural imagery. In Portsmouth, one of the few centers of wealth in colonial New Hampshire, households displayed imported prints or religious paintings, bringing a faint echo of European styles into the region. Yet even here, the dominant tendency remained toward sobriety and restraint.

The Shaker communities that would later flourish in Enfield and Canterbury introduced a new layer of religious aesthetics—simple lines, balanced forms, and an avoidance of ornament. While their fully developed art belongs to a later chapter, the seeds of their influence were already present in the colonial commitment to clarity, utility, and order.

Unexpectedly, some of the most expressive early works were not explicitly religious at all but symbolic in ways that blurred the line between sacred and secular. A weathervane shaped like a fish or a rooster might carry both practical function and Christian allegory. A quilt stitched with stars could echo both celestial order and patriotic sentiment. This blending of symbol and use gave New Hampshire’s early art its particular character: plain yet layered, restrained yet resonant.

The early centuries of New Hampshire’s art history may lack the names of great masters, but they established the foundation for everything that followed. The emphasis on utility infused with quiet beauty, the presence of symbolic carving and painting, and the development of vernacular traditions all ensured that when more recognized artists arrived in the 19th century, they inherited a landscape already rich with meaning. Even the granite underfoot was inscribed with patterns of labor and faith, foreshadowing the state’s long association between natural resources, craftsmanship, and cultural identity.

The story began with the ordinary and the anonymous, but in its very ordinariness lay a distinct aesthetic: one shaped not in academies but in homes, fields, and village greens. From these beginnings, New Hampshire would move toward the painted portraits, sweeping landscapes, and sculptural monuments that defined later centuries—but it never lost that grounding in the plain, durable artistry of its earliest generations.

Portraits of a New State: 18th and Early 19th Century Painting

When New Hampshire formally separated from Massachusetts in 1679 and later entered the Union in 1788, its people began to imagine themselves not just as settlers or colonists but as citizens of a distinct political body. Visual art played a subtle but important role in giving form to this new identity. Portraiture, in particular, became a way for individuals, families, and communities to assert continuity, legitimacy, and place within the unfolding American story.

Traveling portraitists and itinerant styles

Unlike Boston or Philadelphia, New Hampshire had no major academy to train painters in the 18th century. Instead, it relied on itinerant artists—men (and occasionally women) who traveled from town to town, advertising their services through handbills, word of mouth, or even by displaying examples of their work in taverns. They often lodged with their patrons while working, producing portraits that could be executed quickly and affordably.

The style of these portraits reflected the conditions of their making. Without access to European training or expensive pigments, artists worked in bold outlines and flat planes of color. Backgrounds were minimal, often a simple neutral shade or drapery painted in schematic folds. Yet these limitations gave the portraits a directness and immediacy that would later be celebrated as part of America’s distinctive folk tradition.

Artists such as Joseph Badger, Jonathan B. Hudson, and, a little later, William Jennys, made their way through New England, painting likenesses of ministers, sea captains, and prosperous farmers. Their portraits captured not just faces but the tokens of social status: a well-made chair, a ledger book, or a fine dress rendered with particular care. The sitters wanted to be remembered not simply as individuals but as members of a new and respectable society.

In smaller towns, even less-trained painters offered their services, sometimes producing works so naïve in style that they verge on abstraction—elongated hands, oversized eyes, or clothing patterns reduced to geometric motifs. Far from being dismissed, these portraits now hold fascination as expressions of individuality within the limits of skill and circumstance.

Faces of authority: leaders and merchants

Portsmouth, as the most prosperous port in New Hampshire, quickly became the center of formal portraiture. Wealthy merchants who had profited from trade commissioned likenesses that rivaled those found in Boston. These portraits were intended not only for family remembrance but also as symbols of authority within a competitive mercantile world.

Governor John Wentworth, for example, sat for portraits that conveyed not just personal likeness but political stature. Painted in the grand manner, with rich fabrics and confident poses, such works tied New Hampshire’s leaders into a visual tradition that stretched back to European court portraiture. Even as political tides shifted with the Revolution, the portrait remained a means of asserting legitimacy and continuity in uncertain times.

The Revolutionary era itself gave rise to a new kind of portraiture—patriotic in tone, with sitters sometimes shown holding documents, books, or weapons. These images did not merely record appearances but aligned their subjects with the larger ideals of independence, republican virtue, and civic responsibility. In smaller communities, portraits of ministers and town elders served a similar function on a local scale, giving visual form to authority that was both religious and civic.

Three kinds of objects often appeared in these portraits, signaling not only wealth but identity:

- A ledger or book, suggesting education and the written word as markers of civilization.

- A teacup or piece of silverware, evoking refinement and participation in a wider cultural world.

- A globe or map, hinting at trade connections and awareness of global commerce.

These props revealed as much about the ambitions of early New Hampshire society as the faces themselves.

Naïve traditions and the “American primitive”

By the early 19th century, folk portraiture in New Hampshire had developed a recognizable flavor. Artists like Zedekiah Belknap, who painted many portraits across New England, brought a distinctive style marked by stiff poses, sharply defined features, and patterned backgrounds. His sitters often appear frontal and unsmiling, their clothing described in meticulous detail. What might look severe to modern eyes was, for his contemporaries, a dignified assertion of identity.

Other artists produced works even further from academic conventions. Anonymous portraits from small towns show figures with hands out of scale, eyes that dominate the face, or bodies placed against simple flat backdrops. These works, later grouped under the label of “American primitive,” became prized in the 20th century for their candor and unselfconscious stylization. In their time, however, they were valued as sincere likenesses and treasured family heirlooms.

The persistence of such traditions well into the 1830s and 1840s shows the difference between New Hampshire and more cosmopolitan centers. While Boston embraced history painting and grandiose neoclassicism, much of New Hampshire remained content with portraits that emphasized plainness, character, and recognition over theatrical flourish. The state’s rugged geography and scattered towns encouraged this kind of art—personal, direct, and often unpolished.

What surprises many observers is how powerful these portraits remain. Despite their limitations, they convey a gravity and presence that matches the ambition of the society they represented: a people determined to see themselves as permanent, respectable, and enduring. In many ways, the very lack of polish reinforced this message. These were not European aristocrats or polished courtiers, but New Englanders carving out authority in their own sober and pragmatic style.

The rise of portraiture in 18th- and early 19th-century New Hampshire laid the groundwork for the state’s future art. From these faces—sometimes stiff, sometimes luminous—we glimpse a society coming into its own, eager to mark its presence in paint even before landscapes or monuments captured its larger environment. Soon enough, artists would turn their gaze from faces to mountains, finding in the White Mountains the grand subject that would define New Hampshire’s visual identity for the nation.

Landscapes of Granite and Pine: The White Mountains School

By the early 19th century, Americans had begun to look not only at themselves but also at their surroundings as worthy of artistic attention. For New Hampshire, this shift in focus converged on its most striking feature: the White Mountains. Jagged peaks, vast forests, and rushing rivers made the region both forbidding and inspiring. What had once been seen as dangerous wilderness became, through art, a source of national pride and regional identity. Painters who traveled to the White Mountains in the first half of the century helped establish a visual tradition that would place New Hampshire at the heart of American landscape painting.

Influence of Thomas Cole and early sketchers

The White Mountains first gained wide attention when travelers and writers in the early 1800s described their grandeur in journals and travelogues. Among the artists drawn to this new subject was Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School. Cole visited the White Mountains in the 1820s and made sketches that translated the rugged peaks into compositions of sublime beauty. Although Cole is more often associated with the Hudson River Valley, his New Hampshire studies helped establish the White Mountains as a place of artistic pilgrimage.

His vision influenced younger artists who came north to seek both subject matter and inspiration. For them, the mountains were not only impressive scenery but also symbols of endurance, faith, and the power of nature. The raw granite cliffs and stormy skies lent themselves to the Romantic ideals of the period, in which the natural world was understood as a mirror of human emotion and a stage for spiritual reflection.

The very act of sketching in such landscapes carried symbolic weight. Artists hiking up the steep paths to Crawford Notch or Franconia Notch endured the same challenges as the early explorers, suggesting a kind of artistic heroism that paralleled the national expansion into wild frontiers. Their drawings and watercolors, brought back to studios in Boston or New York, became the foundation for larger canvases that circulated widely, helping to establish the White Mountains as a cultural landmark.

Franconia Notch as subject and symbol

If one place became synonymous with New Hampshire landscape painting, it was Franconia Notch. The Notch offered dramatic cliffs, waterfalls, and, most famously, the Old Man of the Mountain—a natural rock formation that resembled a human face. For 19th-century viewers, this formation carried immense symbolic weight, representing the endurance of the Republic and the solemn character of the region.

Painters portrayed the Old Man from countless angles, turning it into one of the most iconic images in American art of the time. Beyond its novelty, the formation embodied the idea that nature itself contained signs of providence and destiny. Travelers to Franconia Notch sought not just views but a kind of revelation, and artists captured this mixture of awe and reflection.

Other features of the Notch also drew attention. The Flume, with its narrow granite walls and rushing water, became a favorite subject for engravings and tourist prints. Artists used light and shadow to emphasize the sense of depth and mystery. Meanwhile, wide views of Mount Lafayette or Cannon Mountain allowed painters to compose sweeping panoramas that suggested both majesty and stillness.

For New Hampshire residents, these images did more than entertain tourists. They helped build a shared identity rooted in the natural environment. The White Mountains came to stand for the state itself, just as the Catskills or the Hudson River defined parts of New York. The mountains were no longer obstacles but emblems—features that gave New Hampshire a distinctive place in the American imagination.

Landscape art and the growth of tourism

The rise of landscape painting in New Hampshire coincided with another cultural shift: the growth of tourism. By the 1820s, improved roads and stagecoach routes made it possible for visitors from Boston, New York, and farther afield to reach the White Mountains. Hotels sprang up at key points such as Crawford Notch, offering accommodations for travelers who wanted to experience sublime scenery without roughing it entirely.

Artists played a crucial role in promoting this tourism. Paintings, engravings, and illustrated travel guides spread images of the mountains to audiences who had never seen them. A family in Boston could purchase a print of the Old Man of the Mountain and feel connected to the grandeur of the region. In turn, more visitors arrived, eager to see in person what they had admired in art.

The interaction between art and tourism created a cycle of mutual reinforcement. As more travelers came, artists found new patrons and new subjects. Hotels displayed paintings in their lobbies, and some even hosted artists as seasonal residents. This gave rise to the first stirrings of artist colonies in the region—a phenomenon that would flourish later with Benjamin Champney and others, but whose roots lay in these early decades of landscape enthusiasm.

This combination of art and tourism also had practical consequences for the land itself. Trails were cleared, scenic overlooks were designated, and natural features were named in ways that echoed the language of art. The White Mountains were no longer simply wilderness; they had become a cultural landscape, shaped by brush and canvas as much as by geology.

The White Mountains School, though less formally organized than the Hudson River School, represented a crucial moment in New Hampshire’s art history. It marked the transition from portraits of individuals to portraits of place, from likenesses of faces to likenesses of land. The granite cliffs, pine forests, and luminous skies captured by early painters were more than decoration—they were declarations of belonging, statements that New Hampshire’s natural environment carried the same weight as the human figures who had earlier filled its canvases.

In this way, the White Mountains became not just scenery but symbol, and the artists who painted them forged a tradition that would dominate New Hampshire’s visual identity for generations.

The White Mountain Painters in Depth

By the mid-19th century, the White Mountains were no longer a little-known wilderness occasionally sketched by adventurous travelers. They had become a full-fledged artistic destination, attracting painters who returned summer after summer, building a body of work that defined New Hampshire’s place in American art. While the Hudson River School provided the philosophical framework—Romantic reverence for nature, the sublime mingling with the picturesque—it was in the White Mountains that this vision found a particularly enduring home. At the heart of this development stood Benjamin Champney, Samuel Lancaster Gerry, John Frederick Kensett, and their circle, who collectively transformed New Hampshire into a permanent artistic landscape.

Benjamin Champney and the artist colony tradition

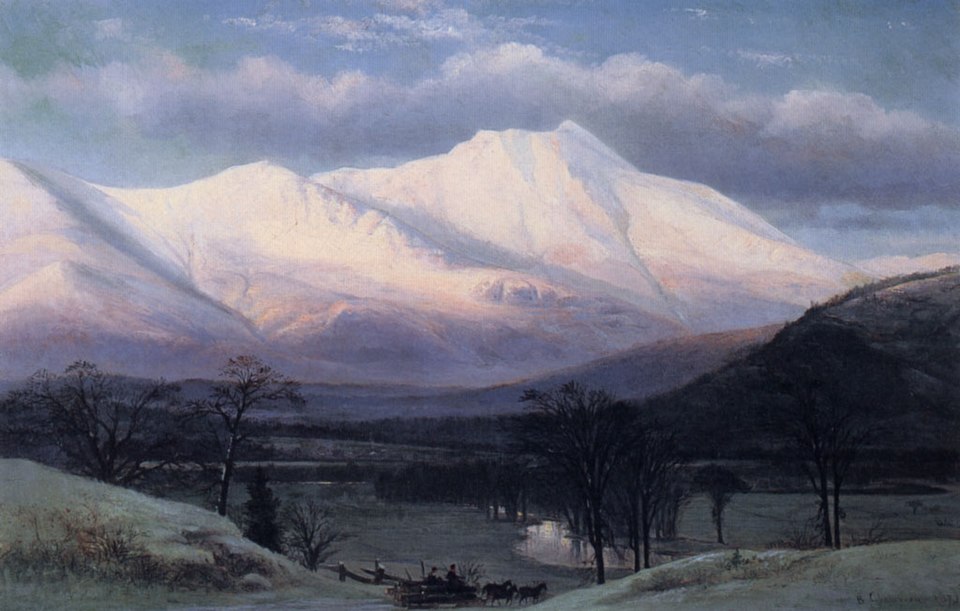

Benjamin Champney, born in New Ipswich, New Hampshire in 1817, is often considered the father of the White Mountain School. Trained in Boston and seasoned by travels in Europe, Champney returned home in the 1850s and established his summer base in North Conway. From there he painted luminous views of Mount Washington, the Saco River, and the surrounding peaks, works that combined careful observation with the idealizing glow characteristic of mid-century landscape painting.

What set Champney apart, however, was not just his own paintings but his role in cultivating a community. His North Conway home became a gathering place for other artists, effectively forming one of the earliest artist colonies in America. Visitors included John Frederick Kensett, Sanford Gifford, and others associated with the Hudson River School. They came for the scenery, but also for the camaraderie—sharing sketching excursions, meals, and conversation about art and the state of the nation.

Champney himself published an autobiography in 1900, Sixty Years’ Memories of Art and Artists, which gave vivid firsthand accounts of these summers in the mountains. He recalled how artists rose early to capture morning light on the peaks, or how sudden storms would force them to retreat, brushes still wet. His writings confirmed that the White Mountains were not just scenery but a living artistic culture.

In fostering this community, Champney ensured that the White Mountains would not be seen as a provincial backwater but as part of the larger national art conversation. He bridged the distance between Boston collectors and New Hampshire landscapes, making the state’s scenery not just admired but marketable. His legacy, then, was both artistic and social: the creation of a sustained environment where art could flourish season after season.

Samuel Lancaster Gerry, John Frederick Kensett, and peers

While Champney was the anchor, other artists contributed distinctive visions. Samuel Lancaster Gerry, originally from Boston, was one of the earliest painters to promote the White Mountains as a subject. His landscapes, often panoramic in scope, emphasized grandeur and atmosphere. Gerry also worked as a teacher and writer, helping to shape critical discourse around landscape painting in New England.

John Frederick Kensett, though not a permanent resident, painted some of the most enduring images of New Hampshire’s peaks and lakes. His style, moving gradually toward the Luminist emphasis on calm light and clarity, gave the White Mountains an almost meditative quality. Unlike the stormy drama favored by Cole, Kensett often depicted tranquil mornings or serene reflections, suggesting a quieter, more spiritual engagement with nature.

Others followed, including Sanford Gifford, Albert Bierstadt, and Jasper Cropsey, each bringing their own sensibility. Bierstadt, with his taste for grandeur, found in Mount Washington a subject equal to his ambitions. Cropsey’s architectural compositions lent order to the wilderness. Collectively, these artists demonstrated the versatility of the White Mountains as a subject: they could be sublime, tranquil, vast, or intimate, depending on the hand that painted them.

The proliferation of such works meant that the White Mountains were seen not only by visitors but also by collectors in Boston, New York, and beyond. A painting of Franconia Notch hanging in a parlor on Beacon Hill carried both aesthetic value and cultural pride, linking urban elites to the rugged character of northern New England.

Art shaping conservation and early preservation efforts

The cultural impact of the White Mountain painters extended beyond canvas into the landscape itself. By the late 19th century, logging and tourism development threatened some of the very vistas that had inspired painters. Paintings and prints of the Old Man of the Mountain or the Flume became rallying images for those who sought to protect these sites, not just as economic assets but as cultural treasures.

While the conservation movement would not fully take shape until later, the groundwork was laid by the visibility artists had given the region. Their works helped elevate the White Mountains from local scenery to national iconography. When the state of New Hampshire established Franconia Notch State Park in the 1920s, it was, in part, the culmination of decades of cultural investment begun by artists who had given the landscape enduring symbolic weight.

Perhaps the most poignant example of this interplay between art and nature came after the collapse of the Old Man of the Mountain in 2003. Though the formation itself vanished, its image survived in countless paintings, prints, and photographs, ensuring its continued presence in the cultural memory of the state. Without the long tradition of artistic representation, the loss might have been purely geological. With it, the collapse became a profound cultural moment, mourned not only as a natural event but as the fading of a symbol.

In this way, the White Mountain painters remind us that art does not merely record a landscape—it shapes its meaning, determines its value, and even influences its future. The brushstrokes of Champney, Gerry, Kensett, and their peers transformed rugged cliffs and valleys into emblems of identity, conservation, and belonging. They made the granite of New Hampshire more than stone; they made it image, idea, and icon.

Carved in Stone: Granite, Monuments, and the Sculptural Tradition

If painting gave New Hampshire its most widely shared artistic images, granite gave the state its enduring reputation. Known as the “Granite State” for good reason, New Hampshire possessed not only an abundance of the stone but also a culture that celebrated its strength, permanence, and utility. From gravestones to civic monuments, granite and other forms of stone carving created a parallel visual history—one rooted not in brush and pigment but in chisel, hammer, and quarry dust.

Granite quarrying and civic pride

By the 19th century, granite quarrying had become one of New Hampshire’s defining industries. Towns such as Concord, Milford, and Barre developed reputations for their stone, which was exported far beyond state lines. Granite’s durability made it the material of choice for public buildings, bridges, and memorials. The very act of quarrying, cutting, and transporting massive blocks of stone demanded engineering skill and a kind of artistry, turning the industry itself into a form of craftsmanship.

Local pride grew around the quarries. Concord granite, for example, was considered among the finest in the country and was used in projects ranging from state capitols to national monuments. When the Library of Congress and parts of the Washington Monument incorporated New Hampshire granite, it carried the state’s identity into the symbolic core of the nation.

Within the state, granite became a marker of civic seriousness. Town halls, courthouses, and libraries built from local stone projected both stability and pride. Just as portraits had asserted the respectability of early New Hampshire citizens, granite architecture declared the endurance of their institutions. The material was not merely functional but symbolic—an assertion that communities were built to last.

War memorials and public statuary

Granite also became central to commemoration. After the Civil War, towns across New Hampshire erected soldiers’ monuments, often in the form of granite obelisks or statues of standing soldiers with rifles. These works, though often designed from standard templates, carried profound local meaning. Each monument stood as a gathering point on Memorial Day, a visible reminder of sacrifice and civic unity.

The use of granite for these memorials underscored their intended permanence. Unlike wood or even softer stone, granite promised endurance for centuries. Carved inscriptions listed names of the fallen, linking local families to the broader national narrative of conflict and reconciliation. The stark simplicity of many New Hampshire war memorials reflected both the material’s nature and the community’s sober character.

In some cases, granite was paired with bronze statuary, as in the larger monuments found in Concord or Manchester. The contrast between the gleam of bronze and the solidity of granite created a visual balance between human representation and enduring foundation. In these works, New Hampshire’s sculptural tradition reached beyond folk carving to join the national trend of monumental public art.

Cemetery sculpture and folk carving traditions

Even before grand civic monuments, New Hampshire’s stone art thrived in its cemeteries. From the 17th through the 19th centuries, gravestones provided one of the most consistent outlets for local stone carving. Early markers featured winged skulls and death’s heads, stern symbols of mortality. By the 18th century, these gave way to cherubs and urns, reflecting a softer, more sentimental view of death and remembrance.

The artistry of gravestone carvers varied widely, but many developed distinctive regional styles. Some favored bold, almost abstract wings framing a face; others carved intricate borders of vines or rosettes. Though anonymous, these carvers left behind a lasting body of work that turned cemeteries into open-air galleries of vernacular sculpture.

Granite’s hardness made it a challenging medium, and many early carvers preferred slate or softer stones. But by the 19th century, improved tools allowed granite to dominate, creating headstones that were less elaborate but more enduring. The shift from softer, highly decorated stones to plainer granite markers reflected broader cultural changes—toward utility, restraint, and permanence over ornament.

Beyond cemeteries, granite also appeared in modest folk uses: boundary markers, millstones, or carved hitching posts. These everyday objects, shaped by necessity, nonetheless carried the same qualities of durability and understated artistry that marked New Hampshire’s broader identity.

- A granite obelisk in a small town square, inscribed with Civil War dead.

- A weathered gravestone with a winged skull staring from its surface.

- A massive block of Concord granite set into a state capitol wall.

Together, such works formed a cultural landscape where stone was never far from sight.

New Hampshire’s sculptural tradition was thus not a secondary footnote but a parallel stream to its painting. While Champney and Kensett celebrated the mountains on canvas, quarrymen and carvers gave shape to the very material of those mountains, transforming it into civic symbols, memorials, and enduring records of life and death. Granite was both medium and message: strong, plain, unyielding, yet capable of refinement in the hands of skilled artisans.

If the White Mountain painters gave New Hampshire its romantic image, the stone carvers gave it permanence. One spoke to imagination, the other to endurance. Together, they defined the state’s artistic character in the 19th century—a balance of vision and solidity, of beauty and bedrock.

Regional Crafts and Folk Traditions

While granite monuments and mountain landscapes projected New Hampshire’s image outward, the quieter heart of its artistic life remained in homes, barns, and village workshops. Regional crafts and folk traditions carried forward an aesthetic of usefulness joined with beauty—an approach deeply embedded in New England culture. These works were not usually signed or displayed in galleries, yet they formed the fabric of daily life and conveyed values of order, thrift, and community pride.

Quilts, hooked rugs, and household artistry

The long winters of New Hampshire gave rise to an especially rich tradition of textile art. Quilting, a necessity for warmth, quickly developed into a decorative form that reflected both individual creativity and shared community practice. Women gathered for quilting bees, where the labor of stitching also became an occasion for social exchange. Many quilts survive with patterns that blend local inventiveness with widely circulating designs, such as the log cabin, star, or nine-patch.

Hooked rugs, made from scraps of cloth pulled through a backing of burlap or linen, were another widespread form of household art. They were practical floor coverings but also canvases for imagination. Designs ranged from geometric borders to pictorial scenes—farmhouses, animals, even patriotic motifs. The very act of repurposing discarded cloth into visual pattern reflects a distinctly New England aesthetic: making beauty out of economy, turning frugality into artistry.

Embroidery and samplers also played a role, especially in the education of young girls. A sampler stitched with alphabets, verses, or decorative borders served both as training in literacy and as a demonstration of skill. Some samplers included images of houses, trees, and symbolic motifs that link them to broader artistic traditions of the region. These works, though often confined to private spaces, endure as some of the most intimate expressions of early New Hampshire artistry.

Three textile motifs frequently appear in surviving examples, each with its own resonance:

- Stars and geometric shapes: symbols of order and aspiration.

- Floral patterns: reminders of seasonal cycles and domestic beauty.

- Animals or farm scenes: reflections of daily rural life.

Through such works, households inscribed their values into objects used every day, blurring the line between the practical and the aesthetic.

Shaker design principles in Enfield and Canterbury

Among the most striking craft traditions in New Hampshire came from the Shaker communities established in Enfield (1793) and Canterbury (1792). The Shakers, a religious society known for communal living and strict devotion, infused every aspect of daily life with their principles of simplicity, utility, and harmony.

Their furniture exemplified these ideals. Straight lines, minimal ornament, and fine proportions gave Shaker chairs, tables, and cupboards a timeless quality. Every element had a purpose, and decoration was avoided unless it also served function. The result was a design language that later generations, especially in the 20th century, recognized as proto-modernist in its clarity.

Beyond furniture, Shakers produced textiles, oval wooden boxes, and tools with the same philosophy. Even their meetinghouses, painted in light colors with unbroken lines, embodied a serene balance between use and spirit. For the Shakers, beauty was not something added after utility—it was the natural outcome of work done well and faithfully.

The contrast with mainstream New England craft traditions was striking. Where rural families often decorated their quilts or gravestones with exuberant motifs, Shakers pursued restraint. Yet both approaches carried a deep artistry, one in ornament, the other in purity. Together, they enriched New Hampshire’s artistic character with complementary visions of beauty.

Woodenware, furniture, and functional beauty

Outside the Shaker communities, New Hampshire craftsmen developed strong traditions in woodenware and furniture. Chairmakers, cabinetmakers, and turners supplied local households with pieces that balanced sturdiness and elegance. Many workshops operated on a small scale, producing items that reflected both local timber resources and regional taste.

Painted furniture became especially popular in the early 19th century. Brightly colored chests, bedsteads, and chairs often featured stenciled or freehand decoration, sometimes imitating more expensive inlaid patterns. These works, often dismissed in their own time as “country” versions of refined urban styles, are now prized for their bold color and inventive designs.

Woodenware such as bowls, ladles, and pails also carried aesthetic touches. A cooper shaping a barrel might add subtle chamfering to the staves, or a turner making a bowl might refine the curve to a graceful sweep. These gestures of form elevated utilitarian objects into works of understated artistry.

The persistence of such crafts throughout the 19th century speaks to the resilience of local traditions even as industrialization advanced. Factories in Manchester and other mill towns produced textiles and goods on a massive scale, yet handmade furniture, quilts, and rugs continued to hold meaning, not only for their function but for the human touch they carried.

New Hampshire’s folk and craft traditions reveal a different kind of art history—one less about galleries and fame than about continuity, community, and daily life. From a Shaker chair to a hooked rug on a farmhouse floor, these objects spoke of lives lived with care and imagination. They remind us that artistry can be as much about rhythm in stitches or curve in wood as about the sweep of a brush on canvas.

Where the White Mountain painters gave New Hampshire national visibility, these household traditions gave it depth. They carried forward an aesthetic rooted in plainness, thrift, and skill, shaping not only how homes looked but how families understood the balance of beauty and necessity. In their quiet endurance, they remain as much a part of the state’s artistic legacy as the grand landscapes that hung in Boston parlors.

The Shaker Aesthetic: Purity, Utility, and Harmony

Among New Hampshire’s most distinctive contributions to American art and design was the work of the Shaker communities at Canterbury and Enfield. While other artisans across the state balanced decoration and function, the Shakers pursued an aesthetic rooted in their spiritual convictions. For them, every chair, cupboard, or box was an act of devotion, shaped by the principle that “beauty rests on utility.” The result was an artistic tradition that, though once seen as austere, came to influence some of the most admired currents of American craftsmanship.

Enfield Shaker Village as a working community

The Shaker settlement in Enfield, founded in 1793 on the shores of Mascoma Lake, developed into one of the largest Shaker villages in the country. At its peak, it housed more than 300 members living in orderly dwellings, working fields, and workshops. Life was communal, celibate, and strictly regulated, but within these boundaries flourished a remarkable culture of making.

Every building and object served a clear purpose. The Great Stone Dwelling, completed in 1841, remains one of the most striking pieces of Shaker architecture: a massive six-story structure built from local granite, with balanced windows, clean lines, and no unnecessary ornament. Its imposing simplicity embodied both practicality and symbolic strength.

Workshops at Enfield produced chairs, oval boxes, brooms, textiles, and other goods that were sold to outsiders as well as used within the community. These objects, while plain, carried a refinement of proportion that gave them quiet elegance. A Shaker chair, for example, with its straight ladder-back and delicately turned spindles, achieved beauty not through decoration but through balance and clarity of form.

Life in the village revolved around labor and worship, but the two were not seen as separate. To make a chair, bake bread, or sweep a floor was to participate in spiritual discipline. The harmony between craft and belief gave Shaker objects a resonance beyond their material form.

Spiritual ideals expressed through design

Shaker design was not an aesthetic accident but a direct outgrowth of theology. The community valued humility, order, and the elimination of excess, and these principles shaped every artifact. Ornament was avoided because it could distract from purpose or encourage vanity. At the same time, work was expected to be thorough, careful, and exact, reflecting the Shaker commitment to perfection in both spiritual and material life.

This philosophy produced objects of remarkable coherence. An oval wooden box, bent from thin strips of wood and secured with swallowtail joints, was efficient for storage, but its proportions also created visual harmony. A peg rail running along a wall allowed chairs to be hung neatly when not in use, maximizing space while also creating a rhythmic visual line. A Shaker cloak, plain in cut and color, expressed modesty while also achieving elegance through restraint.

Music and dance, central to Shaker worship, reinforced these values. Hymns praised simplicity, and the circular dances of Shaker meetings echoed the balance and symmetry of their visual culture. The same spirit that guided their architecture and crafts animated their spiritual life—a seamless integration of art, labor, and devotion.

Lasting influence on later American craftsmanship

For much of the 19th century, outsiders regarded Shaker objects as plain or even severe. Yet by the early 20th century, collectors and designers began to recognize their significance. As industrial goods became more ornate and mass-produced, the clarity of Shaker design appeared refreshing. Furniture makers of the Arts and Crafts movement admired Shaker integrity of construction, while modernists found inspiration in their clean lines and absence of excess.

Museums began to collect Shaker furniture, textiles, and tools, preserving them as exemplary expressions of American design. The simplicity that once seemed austere came to be celebrated as timeless. Today, Shaker chairs and boxes are displayed not only in regional museums but in institutions of international standing, acknowledged as milestones in the history of design.

The influence of Shaker principles can be traced in everything from Scandinavian modern furniture to minimalist architecture. Designers who value “form follows function” echo the Shaker conviction that utility and beauty are inseparable. Even the contemporary enthusiasm for uncluttered living and simple forms carries a faint echo of Shaker ideals, though often stripped of the religious framework that originally gave them meaning.

In New Hampshire itself, the legacy of the Shakers remains tangible. The Canterbury Shaker Village and Enfield site preserve buildings and artifacts, offering a glimpse into a way of life that once combined spiritual fervor with extraordinary craftsmanship. Visitors walking through a Shaker dining hall or examining a handmade box can still sense the conviction that beauty emerges not from ornament but from integrity of purpose.

The Shaker aesthetic stands as one of New Hampshire’s most enduring artistic legacies. Where the White Mountain painters exalted nature and the granite carvers proclaimed permanence, the Shakers revealed how beauty could arise from discipline, humility, and faith. Their work invites reflection not on what is added but on what is pared away, reminding us that sometimes the purest artistry lies in simplicity.

The Lure of Summer: Artists’ Colonies and Seasonal Creativity

By the late 19th century, New Hampshire’s art world no longer revolved solely around rural crafts or solitary landscape painters. Instead, the state became home to vibrant summer colonies that drew leading artists, writers, and intellectuals. These gatherings transformed small towns into seasonal cultural centers, where ideas and styles were exchanged as readily as meals and sketching trips. In the Dublin and Cornish colonies in particular, New Hampshire offered both seclusion and inspiration: a place where artists could work in peace while also finding fellowship with peers.

Dublin Art Colony and Abbott Handerson Thayer

The Dublin Art Colony, situated in the Monadnock region, emerged in the 1880s and 1890s. Drawn by the striking silhouette of Mount Monadnock and the serene beauty of the surrounding countryside, artists and writers began to settle in the area, often building summer houses that doubled as studios. The most influential figure here was Abbott Handerson Thayer, a painter known both for his portraits and for his deeply spiritual depictions of angels and allegorical figures.

Thayer moved permanently to Dublin in the 1890s, and his presence attracted other artists and cultural figures. His own work reflected the dual appeal of the colony: on one hand, intensely personal and visionary, on the other, rooted in the quiet natural beauty of southern New Hampshire. His portraits of his children, painted against the backdrop of Monadnock’s slopes, blend intimacy with grandeur.

The Dublin colony was not limited to painters. Writers such as Mark Twain and composer Amy Beach also spent time in the area, contributing to a lively cross-pollination of artistic forms. The mountain itself became a shared symbol, appearing not only in paintings but in poems, essays, and songs. Monadnock came to stand for constancy, clarity, and the enduring power of nature—qualities that artists sought to capture in their own mediums.

The colony thrived in part because it offered both seclusion and connection. Artists could retreat into their studios, yet still participate in shared meals, excursions, and discussions. The Dublin summers became a kind of seasonal academy, informal yet intensely creative, where artistic boundaries blurred in ways that enriched all participants.

Cornish Colony and Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Even more influential was the Cornish Colony in the Upper Connecticut River Valley, centered around the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Saint-Gaudens, one of America’s leading sculptors of the late 19th century, settled in Cornish in 1885, drawn by the rolling hills and the tranquility of rural New Hampshire. His estate, known as Aspet, became both home and studio, and gradually attracted a circle of artists, writers, architects, and actors who gathered there each summer.

The Cornish Colony was remarkable for its range of talent. Painters such as Thomas Wilmer Dewing, writers like Winston Churchill (the American novelist, not the British statesman), and architects including Charles Platt all spent seasons in Cornish. Their presence transformed the small town into a hub of artistic exchange, where sculpture, painting, architecture, and literature mingled freely.

Saint-Gaudens himself was at the height of his career during these years, producing monuments such as the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial in Boston and the Adams Memorial in Washington, D.C. His work embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance—classical form combined with modern sensibility. The presence of such a figure gave Cornish both prestige and gravitational pull, turning it into one of the most important artist colonies in the country.

What distinguished Cornish from Dublin was its scale and diversity. While Dublin was largely centered on a few painters and the landscape of Monadnock, Cornish became a cosmopolitan gathering of many disciplines, united less by a single symbol than by the shared energy of Saint-Gaudens’s leadership. The summers there were both productive and social, remembered for theatrical performances, musical evenings, and a sense of community that blended New England quiet with cosmopolitan sophistication.

Exchanges between painting, literature, and sculpture

The colonies of Dublin and Cornish demonstrated how art in New Hampshire had entered a new phase. No longer isolated or purely local, the state had become a magnet for nationally recognized figures who sought both inspiration and retreat. Their presence marked New Hampshire not only as a subject for painting but as a setting for artistic life itself.

In Dublin, the vision of Thayer and his circle connected the natural landscape with allegorical and spiritual art. In Cornish, the presence of Saint-Gaudens anchored a network of exchange between sculpture, painting, literature, and architecture. Together, they showed how the state could nurture creativity across forms, and how the rhythm of summer—intense work followed by communal leisure—created an atmosphere uniquely suited to artistic production.

These colonies also reinforced the image of New Hampshire as a place of purity and renewal. For urban artists weary of New York or Boston, the state offered fresh air, clean lines of mountain and meadow, and the possibility of both solitude and fellowship. The very landscape that had drawn the White Mountain painters now played host to a new generation of creators, who found in its hills not only scenery but community.

The legacy of these colonies endures. Saint-Gaudens’s home became a national historic site, preserving his studio and gardens. Dublin remains associated with the vision of Monadnock and the presence of Thayer. More broadly, the colonies marked a turning point in New Hampshire’s art history: from the solitary image of mountains or gravestones to the lively sound of many voices, gathered for a season of shared imagination.

Saint-Gaudens and the American Renaissance in Cornish

If the White Mountain painters gave New Hampshire its natural imagery, Augustus Saint-Gaudens gave it a place at the center of America’s cultural ambitions. Widely considered the greatest sculptor of his generation, Saint-Gaudens settled in Cornish, New Hampshire, in 1885 and transformed his home into a creative hub that became one of the nation’s most important artist colonies. His work and his presence embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance: a moment when American art aspired to match the grandeur of Europe while also asserting its own character.

The sculptor’s move to New Hampshire

Saint-Gaudens was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1848 and raised in New York City, where he trained as a cameo cutter before studying in Paris and Rome. By the 1880s he was already acclaimed for commissions such as the Farragut Monument in New York and was sought after for public memorials. His move to Cornish was motivated partly by health—he suffered from tuberculosis and sought the cleaner air of rural New England—and partly by a desire for peace and stability.

He purchased a house he called Aspet, after his father’s birthplace in France, and gradually transformed it into both residence and studio. The Cornish landscape, with its rolling hills and broad river valleys, provided not only a restorative setting but also a stage for his creative vision. Working in barns converted to studios, Saint-Gaudens produced some of his most celebrated pieces while surrounded by assistants, apprentices, and visitors.

The presence of the sculptor quickly drew others. Cornish, once an unassuming village, became the center of a vibrant colony of painters, writers, architects, and musicians who gathered each summer. While many came for the social life, Saint-Gaudens himself worked with relentless discipline, producing commissions that defined the American approach to monument and memorial.

His atelier and circle of artists

At Aspet, Saint-Gaudens established an atelier that operated much like those of Renaissance masters. Teams of assistants helped execute large commissions, while apprentices learned the craft by working under his guidance. The studio was a hive of activity, where clay models, plaster casts, and bronze forms filled the space. Visitors described the atmosphere as both industrious and electric, with Saint-Gaudens at the center, shaping details while orchestrating the efforts of many hands.

Among the works produced during his Cornish years were the Shaw Memorial in Boston, commemorating Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and the Adams Memorial in Washington, D.C., often called the “Grief Monument” for its haunting, contemplative figure. Both works embodied the fusion of realism and allegory that defined his style: grounded in human presence, yet elevated by symbolic resonance.

The colony that grew around him included Thomas Wilmer Dewing, whose delicate paintings of women in restrained interiors contrasted with the monumental bronze outside, and architect Charles Platt, who later helped redesign parts of the Aspet estate itself. Writers, musicians, and actors added to the mix, creating a cultural environment where different arts fed one another. Evenings might include music, readings, or amateur theatricals, while days were given to concentrated work.

For younger artists, time in Cornish was both training and inspiration. The colony demonstrated that American art could thrive in a rural setting, drawing from European traditions yet rooted in American soil. Saint-Gaudens’s studio embodied this balance: classical in method, yet national in subject matter and ambition.

Legacy preserved as a national historic site

Saint-Gaudens died in 1907, but his impact continued long after. His estate eventually became the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, established in 1965 as the first such designation in New Hampshire. Today, visitors can walk through his studios, gardens, and grounds, experiencing both the sculptures and the environment that shaped them. The site preserves not only his work but also the atmosphere of the Cornish Colony, with its blend of art, landscape, and community.

His influence extended into many fields. In sculpture, he set the standard for public monuments, combining narrative clarity with formal elegance. His Shaw Memorial in particular reshaped how Americans remembered the Civil War, offering an image at once specific to its subject and universal in its evocation of sacrifice. In design, his work on U.S. coinage—including the celebrated $20 gold double eagle—demonstrated how even functional objects could achieve beauty and dignity.

More broadly, Saint-Gaudens embodied a moment when American art aspired to grandeur without losing sincerity. His Cornish years showed that such ambition did not require the bustle of New York or Paris; it could flourish in a New England village, nourished by granite hills and quiet labor.

For New Hampshire, his presence elevated the state’s artistic profile immeasurably. No longer just the land of rugged landscapes and folk traditions, it became home to one of the greatest sculptors of the age. The Cornish Colony that grew around him added breadth, but Saint-Gaudens himself remained the anchor—a figure whose work continues to stand in city squares, cemeteries, and national spaces across the country.

His art reminds us that sculpture, at its best, can both honor the past and shape the future. In Cornish, that vision took root in granite soil and blossomed into bronze forms that still carry the weight of memory and aspiration.

Modernism in the Granite State

The arrival of modernism in the early 20th century sent ripples through every corner of American art, from New York galleries to small-town studios. In New Hampshire, the shift was more measured, even hesitant. The state’s artistic traditions—rooted in landscape, craft, and community—did not easily yield to the fractured forms, bold abstractions, and experimental philosophies of the new age. Yet modernism did find its way into the Granite State, carried by artists trained in urban centers, by the influence of regional institutions, and by the persistent question of how New Hampshire’s identity might be expressed in a rapidly changing world.

Regional responses to abstraction

While modernist experimentation flourished in New York with artists like Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, many New Hampshire painters remained attached to recognizable forms. Mountains, lakes, and farms continued to dominate subject matter, but the treatment of these themes gradually shifted. Lines became looser, color more expressive, and compositions more daring. Instead of the meticulous realism of the White Mountain painters, artists allowed brushwork to suggest rather than define, hinting at mood as much as topography.

Some New Hampshire artists resisted abstraction outright, viewing it as foreign or disconnected from the region’s sober traditions. Others adopted it selectively, using modernist techniques to reinvigorate old subjects. A view of Mount Monadnock, for example, might be rendered with bold color planes or simplified shapes, turning the mountain into an emblem rather than a detailed record.

This tension—between fidelity to local subjects and openness to international styles—defined much of New Hampshire’s relationship to modernism. Unlike cosmopolitan centers, the state did not produce avant-garde manifestos or radical collectives. Instead, modernism entered quietly, through gradual adaptation, producing works that balanced new aesthetics with local attachment.

New Hampshire artists in Boston and New York

For many artists raised or working in New Hampshire, full engagement with modernism required travel. Boston’s museums and schools provided an entry point, exposing students to Impressionism and post-Impressionism. The Museum of Fine Arts School and the Boston Art Club drew many New Hampshire-born artists who then returned home with broadened perspectives.

Others made the leap to New York, where the Armory Show of 1913 introduced Americans to Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism. A handful of New Hampshire artists attended or exhibited in such venues, bringing back ideas that filtered into their work. Yet even for those who embraced modernist language, the subjects often remained rooted in local scenery—barns, mills, or river valleys transfigured by angular forms or heightened palettes.

This pattern produced a distinct hybrid: art that was modern in technique but regional in subject. Instead of abandoning place for pure abstraction, many New Hampshire artists sought to reconcile innovation with recognition. Their work offers a kind of negotiation, a dialogue between the universal and the particular.

Experimentation and mid-century directions

By the mid-20th century, modernism had become part of the mainstream, and New Hampshire saw a broader range of experiments. Abstract expressionism, though centered in New York, found echoes in the state through artists who sought to capture the energy of brushstroke and gesture while still responding to the landscape. Others explored printmaking, photography, or sculpture with new materials, expanding the scope of the state’s artistic life.

Institutions such as Dartmouth College’s art department provided a platform for modernist exploration. Visiting artists brought fresh ideas, and exhibitions exposed local audiences to international trends. The Hood Museum, later established, would deepen this engagement, but even before its founding, Dartmouth played a central role in connecting New Hampshire to the broader modernist movement.

Yet resistance remained. For many towns, traditional realism continued to define local exhibitions and fairs. A painting of a farmstead or a mountain view was more likely to find a buyer than a bold abstraction. This conservatism did not stifle creativity but ensured that modernism in New Hampshire often carried a different tone—less radical, more adaptive, and always shadowed by the enduring presence of the land.

Three themes emerged in this mid-century art:

- Landscape transformed: old subjects painted with new techniques, balancing tradition and innovation.

- Urban influence: artists moving between New Hampshire and metropolitan centers, bringing back modernist ideas.

- Institutional mediation: colleges, museums, and societies introducing audiences to modernism while negotiating local taste.

Modernism in the Granite State was never a wholesale revolution. It arrived gradually, reshaped by the state’s attachment to its environment and its skepticism toward extremes. But precisely in this tension lies its interest: New Hampshire’s modernism was not a break but a weaving together, a conversation between past and present, permanence and change.

By mid-century, the state could no longer be seen as an isolated backwater of art. Its artists had engaged—sometimes cautiously, sometimes boldly—with the great currents of modernism, ensuring that even amid granite hills and quiet villages, the winds of the 20th century were felt.

Institutions and Collectors: Building a Cultural Infrastructure

For much of New Hampshire’s early history, art existed in private homes, churches, or scattered workshops. Portraits hung in parlors, hooked rugs warmed floors, and gravestones lined village cemeteries, but there were few dedicated spaces to preserve or display art. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, the state began to build the cultural infrastructure that would sustain its artistic life into the modern era. Museums, colleges, and local societies became central not only to collecting and exhibiting works but also to shaping the public’s sense of New Hampshire’s artistic identity.

The Currier Museum of Art in Manchester

The most significant of these institutions was the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester. Founded in 1929 through a bequest from Moody Currier, a former governor of New Hampshire, and his wife Hannah, the museum was envisioned as a place where art could enrich the lives of the city’s citizens. Manchester, with its powerful textile mills and large immigrant population, was an industrial hub rather than a cultural one. The creation of an art museum there was both bold and aspirational, signaling a desire to balance economic vigor with aesthetic cultivation.

From the start, the Currier collected broadly, acquiring European Old Masters, American landscapes, and decorative arts. Over time, its holdings grew to include significant works by American modernists as well as important examples of regional art. The museum’s decision to preserve and exhibit Frank Lloyd Wright–designed houses later in the 20th century expanded its scope into architecture, linking New Hampshire to international design history.

The Currier provided more than art on walls—it offered lectures, concerts, and community programs that brought culture into everyday civic life. For Manchester residents, it became a place where factory workers’ children might encounter paintings by Monet or O’Keeffe alongside White Mountain landscapes. In this sense, the Currier was not only a museum but also a statement of civic ambition, asserting that art belonged not just to elites but to an entire industrial city.

Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth

If the Currier represented urban ambition, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College embodied the role of academia in shaping New Hampshire’s cultural life. Dartmouth had collected art since the 18th century, but the Hood Museum, formally established in 1985, gave the college a dedicated space to house and display its collections. Its holdings include everything from Assyrian reliefs to contemporary works, but its New England context gives special weight to American painting and regional traditions.

The Hood has served as both museum and teaching resource. For students, it provides direct access to original works, integrating art into a liberal arts education. For the public, it offers exhibitions that place local traditions in dialogue with global art, encouraging viewers to see New Hampshire not as an isolated province but as part of larger currents.

Particularly valuable has been the Hood’s role in preserving and displaying Native American art, reflecting Dartmouth’s long history of engagement with Native peoples, though always framed within the broader academic mission of study and preservation rather than political interpretation. In addition, the museum’s commitment to contemporary art has ensured that New Hampshire audiences remain connected to developments far beyond their borders.

Local art societies and historical associations

Alongside these major institutions, smaller art societies, libraries, and historical associations across New Hampshire have played crucial roles in sustaining cultural life. Organizations such as the New Hampshire Art Association, founded in 1940, have given local artists opportunities to exhibit and sell their work. Historical societies in towns from Portsmouth to Keene have preserved portraits, gravestones, and decorative arts that might otherwise have vanished.

These local efforts reflect the state’s character: decentralized, community-driven, and rooted in pride of place. A town historical society displaying 18th-century samplers or 19th-century portraits may not command national attention, but it anchors cultural identity at the local level. Libraries, too, often hosted art lectures or small exhibitions, making art part of civic rather than strictly elite life.

Three elements typically defined these community institutions:

- Preservation: safeguarding artifacts of local families, churches, and schools.

- Education: using art to instruct children and adults about heritage and taste.

- Connection: linking small towns to the broader state and regional artistic traditions.

Taken together, these institutions created a cultural infrastructure that transformed New Hampshire from a place where art was scattered and private into one where it was public, shared, and enduring. The Currier and Hood placed the state on the national cultural map, while local societies ensured that the smaller, humbler works of daily life were not forgotten.

In this dual structure—cosmopolitan institutions balanced by community efforts—New Hampshire found a cultural identity consistent with its history: ambitious yet grounded, outward-looking yet fiercely local. The infrastructure built in the 20th century made possible the preservation not only of masterworks but also of the everyday artistry that had always been at the state’s core.

The 20th-Century Folk Spirit: Rural Art in Modern Times

Even as modernism and institutional collecting reshaped New Hampshire’s art world, another current ran alongside: the persistence and reinvention of rural folk traditions. In the 20th century, when industrial production and urban culture seemed to dominate American life, New Hampshire continued to nurture self-taught artists, craft communities, and seasonal fairs that kept local artistry visible and alive. These practices offered continuity with the past while also adapting to new audiences, proving that art in the Granite State was not confined to museums and professional studios but remained a living, communal endeavor.

Traditional crafts carried forward

The quilting, rug-hooking, woodworking, and furniture-making traditions of the 19th century did not vanish with industrialization. Instead, they evolved, often maintained within families or revived by historical interest. In many towns, older women passed down quilt patterns to daughters and granddaughters, ensuring that new generations stitched both memory and artistry into fabric. Hooked rugs, once made from necessity, became prized as decorative objects, their bold designs appreciated by collectors as much as by households.

Woodworkers continued to produce bowls, spoons, and furniture, sometimes for personal use, sometimes for small markets or fairs. These works often combined practical durability with local woods—maple, birch, or pine—that gave them a distinctly New England character. The craft revival movements of the early and mid-20th century, which valued handmade objects in an industrial age, found fertile ground in New Hampshire, where the tradition of working with one’s hands had never truly disappeared.

Such continuity was not merely nostalgic. It reflected a deeper cultural habit: the conviction that objects could embody care, skill, and identity, even in an era of mass production. To own a hand-stitched quilt or a turned wooden bowl was to maintain a link with the values of thrift, patience, and artistry that had long defined New Hampshire life.

Self-taught artists and vernacular creativity

Alongside craft traditions, the 20th century also saw the rise of self-taught painters and makers whose works, though outside academic training, carried powerful personal vision. These individuals often painted scenes of daily life, local landscapes, or imaginative subjects with directness and sincerity. Their art, sometimes dismissed as amateur in its own day, later gained recognition as a vital strand of American creativity.

One striking feature of such work in New Hampshire was its rootedness in place. A self-taught painter might render the family farm with barns and animals in simplified but heartfelt forms, or record a town’s main street with a precision that rivaled surveyors. Others turned to symbolic or whimsical subjects, blending folk motifs with personal invention.

Collectors and scholars in the later 20th century began to prize these works as “vernacular” art—creations that revealed local voices and perspectives often overlooked by the mainstream art world. For New Hampshire, these self-taught artists extended the legacy of folk portraitists and gravestone carvers from earlier centuries, proving that art outside institutions remained vibrant and meaningful.

Community fairs and art festivals

Perhaps the most enduring expressions of New Hampshire’s 20th-century folk spirit were the community fairs, festivals, and exhibitions that brought together craftspeople, artists, and audiences. The state fair, county fairs, and town celebrations often included sections for quilts, paintings, woodwork, and other handmade objects. These venues blurred the line between competition and exhibition, giving recognition to everyday artistry alongside livestock contests and agricultural displays.

In the later 20th century, dedicated craft fairs and art festivals grew in prominence. The League of New Hampshire Craftsmen, founded in 1932, became a central institution in promoting handmade work. Its annual fair, held at Mount Sunapee, became one of the oldest and most respected craft fairs in the country, drawing visitors from across New England. There, visitors could see potters at their wheels, jewelers shaping silver, or weavers working looms—continuations of traditions that combined artistry with livelihood.

These fairs did more than sell objects. They created a shared cultural experience, affirming that art was not confined to elite settings but belonged in the rhythms of community life. Children wandered among booths, families admired work together, and craftspeople explained their techniques face-to-face. Such encounters reinforced the value of human skill and imagination in a world increasingly dominated by machines.

- A quilt entered in a county fair, its stitching both competition and legacy.

- A painter displaying small oils of New Hampshire barns at a church bazaar.

- A potter at the League’s fair, hands turning clay before a crowd.

These moments gave ordinary artistry public recognition, strengthening the bond between local identity and creative expression.

The persistence of folk spirit in 20th-century New Hampshire shows that the state’s art history is not a straight line from primitive portraiture to modernist abstraction. It is also a cycle of continuity, where traditions adapt, survive, and flourish in new forms. While the Currier and Hood museums connected the state to national and international art, the fairs, self-taught painters, and craft communities ensured that creativity remained rooted in daily life.

In their combination of endurance and adaptation, these rural traditions carried forward the ethos that had always marked New Hampshire’s art: beauty joined with utility, imagination joined with community, and art not as ornament alone but as part of the fabric of living.

Photography and the New Hampshire Image

When the camera arrived in the 19th century, it did not replace painting in New Hampshire but expanded the ways in which the state was seen, remembered, and shared. From daguerreotypes of townspeople to sweeping vistas of the White Mountains, photography quickly became a vital medium for shaping New Hampshire’s cultural image. Unlike paintings—often costly and confined to galleries or parlors—photographs could be reproduced and circulated widely. By the 20th century, postcards, brochures, and illustrated books had turned New Hampshire’s peaks, lakes, and villages into images familiar far beyond its borders.

White Mountain photography and tourism

The earliest photographs of the White Mountains appeared in the 1840s and 1850s, as daguerreotype studios spread across New England. These fragile, silvery images captured likenesses of visitors rather than landscapes, but soon photographers carried their cumbersome equipment into the mountains themselves. By the 1860s, stereoscopic views—pairs of photographs mounted side by side to create a three-dimensional effect when seen through a stereoscope—became wildly popular. Companies such as Kilburn Brothers of Littleton produced thousands of these views, showing waterfalls, cliffs, and hotels bustling with tourists.

The effect was transformative. For families in Boston, New York, or Chicago, stereographs offered the illusion of standing within Franconia Notch or gazing at Mount Washington. These images did more than depict scenery—they advertised it, feeding the growing tourism industry that sustained hotels, carriage roads, and rail lines. Photography thus played the same promotional role for the mountains that paintings had earlier, but with far greater reach.

The clarity of the camera also altered how people perceived the landscape. Painters might dramatize skies or exaggerate scale for effect, but photographs presented the mountains as they appeared—or at least as they could be framed by a skilled photographer. This sense of authenticity reinforced the White Mountains’ reputation as places of natural wonder, worth seeing “in person” after first encountering them in print.

Pictorialist approaches in the early 20th century

As photography matured into an art form in its own right, New Hampshire’s landscapes continued to inspire. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Pictorialist movement sought to elevate photography beyond documentation, using soft focus, dramatic light, and careful composition to achieve painterly effects. Photographers in New Hampshire applied these techniques to familiar subjects: lakes at twilight, snow-laden pines, or Monadnock looming in atmospheric haze.

One striking quality of Pictorialist photography was its ability to capture mood rather than detail. A misty view of the Connecticut River Valley might echo Kensett’s luminist paintings, while a snow scene could rival a Currier and Ives lithograph in its evocation of New England winter. These works appealed to audiences who still cherished traditional beauty but were open to new mediums.

Photography also documented rural life in ways painting rarely did. Farmers in their fields, mill workers along canals, or children playing in village streets were all captured in candid moments. Such images preserved the texture of daily life in New Hampshire towns, offering historians today invaluable glimpses of clothing, tools, and social habits. What painters idealized, photographers recorded, expanding the scope of what counted as worthy of artistic attention.

Postcards, brochures, and popular imagery

By the early 20th century, photography was everywhere in New Hampshire tourism. Postcards of the Old Man of the Mountain, the Flume, or Mount Washington hotels circulated through the mail, carrying the state’s imagery to every corner of the country. Railroads and hotels produced brochures filled with photographs promising clean air, scenic beauty, and healthy recreation. A single image of a lake or a mountain path could entice a family to spend their summer in the Granite State.

These popular images became part of collective memory. Generations of visitors kept albums filled with postcards and snapshots, many of which survive in attics and historical society collections. They testify not only to personal vacations but also to the broader way New Hampshire presented itself to the world: rugged, pure, healthful, and scenic.

The postcard tradition also democratized art. While few families could afford a painted canvas, nearly everyone could buy and send a photographic card. In this way, photography gave New Hampshire a kind of mass-produced cultural presence, extending its landscapes into countless homes across the country.

- A stereograph of the Flume, viewed through a parlor stereoscope, transporting city dwellers into granite depths.

- A soft-focus print of Mount Monadnock, suffused with evening light, bridging photography and painting.

- A glossy postcard of the Old Man of the Mountain, sent with a brief message: “Wish you were here.”

These forms—commercial yet artistic, intimate yet widespread—made New Hampshire’s image one of the most widely recognized in America.

By the mid-20th century, photography was inseparable from the state’s identity. Painters and sculptors continued their work, but it was often the photograph—whether in a travel brochure, an exhibition print, or a family album—that most powerfully fixed New Hampshire in the national imagination. The mountains, lakes, and villages of the Granite State became not just places to visit but images to collect, share, and remember.

Contemporary Currents: New Hampshire Artists Today

Art in New Hampshire today is neither locked in its past nor detached from it. The landscapes that inspired White Mountain painters still draw brush and camera, yet new voices and new mediums have joined the chorus. Contemporary artists across the Granite State explore painting, sculpture, installation, and environmental projects, often balancing reverence for tradition with curiosity about the present. The state’s art scene is small compared to major cities, but it is diverse, inventive, and sustained by a network of studios, galleries, and community institutions.

Regionalist painters and the persistence of landscape