In the heart of Baden-Württemberg, the city of Karlsruhe became home to one of Germany’s most esteemed art institutions when the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe was founded in 1854. It was established under the patronage of Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden, a progressive monarch known for his cultural interests and support of education. Born on September 9, 1826, Friedrich I sought to position his grand duchy as a hub of intellectual and artistic achievement in the German Confederation. The academy’s founding aligned with a broader 19th-century movement to institutionalize art education throughout Germany’s fragmented territories.

The academy’s initial mission was to provide formal training in fine arts—especially painting and sculpture—to nurture a generation of artists rooted in classical ideals but open to regional expression. Its early curriculum was grounded in drawing from life, anatomy, perspective, and art history, which mirrored the rigorous academic standards seen in Paris and Munich. The location of Karlsruhe, with its blend of urban energy and access to the Black Forest’s natural beauty, provided an inspiring backdrop for young creatives. This combination of environment and instruction helped the school quickly earn a reputable standing among Germany’s art institutions.

The Founding Vision of Grand Duke Friedrich I

Friedrich I, who would later become Grand Duke in 1856 and rule until his death in 1907, saw the arts as a stabilizing cultural force during a time of political flux across the German states. His patronage of the Kunstakademie wasn’t merely symbolic; he ensured generous state funding and even influenced faculty appointments to secure the school’s integrity. Under his reign, Karlsruhe emerged not only as a political center but also as a beacon of artistic instruction and innovation. His vision allowed the institution to attract prominent faculty and students from across Europe.

In its formative years, the school was also instrumental in shaping cultural policy in Baden. The presence of the academy supported museums, theater houses, and public art projects, all of which reinforced Friedrich I’s belief in the arts as a cornerstone of civilization. His marriage to Princess Louise of Prussia in 1856 further bolstered his stature, indirectly linking the academy to Prussian intellectual networks. From its very foundation, the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe stood for the blending of state responsibility with cultural cultivation—a distinctly conservative principle.

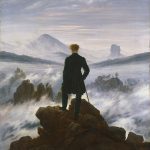

A Hub for German Romanticism and Realism

By the latter half of the 19th century, the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe had established itself as a center for the Romantic and Realist traditions in German art. Under the leadership of Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, appointed as the first director in 1854, the academy emphasized the deep emotional resonance of Romanticism and the truthful depiction of nature found in Realism. Schirmer, born in 1807 in Jülich, had previously taught at the Düsseldorf Academy, where he refined his landscape painting style that would become foundational to Karlsruhe’s artistic identity. His direction laid the groundwork for a pedagogical model that respected discipline, moral order, and beauty rooted in creation.

Schirmer died in 1863, but his short tenure left a lasting imprint on the institution. He introduced structured plein air study sessions, urging students to paint directly from the varied countryside around Karlsruhe, which created a powerful regional character in the school’s output. This approach combined with his spiritual idealism formed a unique educational philosophy—one where mastery of nature went hand-in-hand with moral cultivation. His students, like Gustav Schönleber and Hans Thoma, would later become influential painters in their own right.

Influential Faculty in the 19th Century

The academy flourished as it welcomed an array of capable instructors whose influence spread throughout Germany. The sculptor Hermann Volz and history painter Ferdinand Keller were among the notable faculty of the late 19th century. Volz, who joined the academy in 1869, brought a strong sense of monumentality and reverence for classical form, traits that made him a pillar of Karlsruhe’s sculpture instruction. Keller, born in 1842, became director in 1880 and expanded the curriculum to reflect historical and patriotic themes—an emphasis in line with the national sentiment building toward German unification.

These instructors attracted students who shared a respect for tradition, structure, and German cultural heritage. Art at Karlsruhe during this time did not pursue the avant-garde or reject order, but instead sought excellence through mastery of inherited forms. A balance of Romantic emotion and Realist precision continued to define its teachings. The academy maintained strong ties to museums and private patrons, reinforcing its position in the cultural fabric of southern Germany.

The Academy During the Wilhelmine Empire and Weimar Period

The turn of the 20th century brought both innovation and tension to the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe. Germany, under the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, was undergoing rapid industrialization and modernization. While the empire embraced technical progress, Wilhelm maintained conservative tastes in art, often favoring the heroic and historic over abstraction. The academy adapted to these expectations, fostering work that celebrated German nationalism, rural virtue, and classical form, yet it could not remain untouched by modern trends emerging in cities like Munich and Berlin.

During this period, the academy saw increased experimentation with styles like Symbolism and Jugendstil (Art Nouveau), particularly among younger faculty and students. Influences from the Vienna Secession and French Impressionists crept in through exhibitions and publications. Yet the academy remained cautious; these styles were never fully adopted into the core curriculum. Instead, professors encouraged students to innovate within the framework of realism and disciplined technique.

Artistic Evolution in a Changing Germany

The Weimar Republic, declared in 1919 following Germany’s defeat in World War I, brought about seismic political and cultural changes. For the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe, this meant both disruption and opportunity. On one hand, the collapse of monarchy and resulting instability led to budget constraints and faculty turnover. On the other hand, it allowed the academy to cautiously broaden its instructional scope and explore new artistic paradigms.

Faculty during this time, including the painter Karl Hubbuch, began to push the boundaries of academic realism. Born in 1891, Hubbuch was associated with Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a movement that emerged in reaction to expressionism’s excesses. His sharp, socially observant works reflected the disillusionment of the era. Although controversial to traditionalists, Hubbuch’s influence hinted at a possible reconciliation between innovation and academic structure.

Impact of the Third Reich and World War II

The rise of the National Socialist regime in 1933 cast a long shadow over Germany’s cultural institutions, and the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe was no exception. Artists who embraced modernism or challenged the regime’s ideological preferences were denounced and removed from their positions. Curricula were altered to conform to the regime’s preferred aesthetic, emphasizing rural romanticism, martial vigor, and ethnic purity. Academic freedom was curtailed, and any deviation from officially sanctioned styles could result in professional ruin.

Professors who had previously experimented with New Objectivity or abstract techniques found themselves in ideological conflict with the new government. Several instructors and students were dismissed or pressured into silence. Artworks by controversial artists were confiscated, labeled as “degenerate,” and excluded from public view. The state imposed strict guidelines that emphasized monumental art celebrating race, labor, and the military spirit. In this environment, the academy had to tread carefully or risk closure.

Degenerate Art and Institutional Survival

One of the academy’s tragic losses during this period was the forced resignation of Karl Hubbuch, who was removed due to his association with politically subversive movements. His sharp critique of societal and political hypocrisy, once tolerated in the Weimar years, had become unacceptable. Many of his students dispersed, and their careers were stifled or redirected. The academy, now under heavy state scrutiny, was compelled to comply with directives that stifled genuine creativity and reduced its prestige.

During World War II, Karlsruhe was heavily bombed, and the academy’s facilities suffered significant damage. Portions of its archives and student works were lost in the destruction. Art instruction continued in a limited capacity, often relocated or merged with other institutions. As the war dragged on, the academy’s resources were increasingly diverted or depleted, and its role became more ceremonial than educational. Still, it managed to preserve its core staff and some semblance of curriculum through sheer resilience and administrative maneuvering.

Post-War Rebuilding and Artistic Renewal

In the aftermath of Germany’s surrender in 1945, the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe began a long process of physical, institutional, and ideological rebuilding. The first task was to repair its damaged buildings and reassemble faculty, some of whom had been dismissed during the war or had fled abroad. The Allied occupation authorities allowed the academy to reopen with a restructured curriculum free from propaganda influence. As Germany moved toward reconstruction, so too did the academy evolve into a space for artistic rebirth.

The 1950s and 1960s marked a profound change in the academy’s direction. Under the leadership of modernist thinkers and artists, the school expanded beyond classical painting and sculpture to include graphic design, abstract art, and critical theory. Otto Laible, a painter born in 1898, was instrumental in this shift. He had survived the National Socialist era in relative obscurity but became a leading post-war instructor advocating for freedom of form and critical engagement with history.

Reinvention in the Mid-20th Century

Erwin Heinle, an architect and educator involved in post-war urban renewal, also contributed significantly to the academy’s revival. Under their guidance, students were encouraged to question, reinterpret, and reform the traditions they inherited. This balance of respect for foundational training and openness to experimentation set the tone for the modern academy. New facilities were built to accommodate expanded disciplines, including media and performance art.

As Germany transitioned from ruins to a new republic, the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe reclaimed its place among Europe’s top-tier institutions. Public exhibitions returned, often showcasing bold, sometimes controversial works that would have been banned a decade earlier. The academy also resumed its ties with international institutions and hosted visiting lecturers from France, Italy, and the United States. These cross-cultural exchanges accelerated its modernization and global relevance.

Notable Alumni and International Influence

Over the decades, the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe has been home to numerous artists whose influence stretched well beyond Germany. Markus Lüpertz, born in 1941, studied and later taught at the academy, eventually becoming one of the most significant figures in post-war German painting. His “German motifs” series confronted national memory with audacious color and symbolism. Lüpertz went on to become rector of the Düsseldorf Academy but always credited Karlsruhe for shaping his artistic discipline.

Another celebrated figure is Horst Antes, born in 1936, who studied under Hannes Neuner and developed the iconic “Kopffüßler” (head-footer) figures that became synonymous with postmodern German art. Antes taught at Karlsruhe for several years and influenced a generation of visual artists who bridged expressionism and surrealism. The academy provided him with both the technical foundation and the creative liberty to define his style. Through exhibitions across Europe and the Americas, Antes helped spotlight the school’s international relevance.

Artists Who Shaped the Modern World

Georg Baselitz, though more closely associated with Berlin and Dresden, briefly studied at Karlsruhe in the late 1950s. His upside-down figures and raw depictions of post-war trauma shook the European art scene. While his time at the academy was brief, the foundational skills and theoretical exposure there played a role in shaping his defiant visual language. Baselitz’s later rejection of academicism only underscores the school’s significance as a starting point even for those who rebelled against it.

Beyond these marquee names, countless lesser-known but globally active artists emerged from Karlsruhe. Many became professors in prestigious art programs across Europe and North America. Others found careers in design, public sculpture, or digital media. The academy’s alumni network is a testament to the breadth and depth of its influence, transcending genres, borders, and ideologies.

The Academy Today: Curriculum, Campus, and Culture

Today, the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe maintains its legacy as a rigorous yet forward-looking institution. Its curriculum spans painting, sculpture, photography, new media, and theory, offering a well-rounded education steeped in tradition but unafraid of innovation. The campus, located in central Karlsruhe, combines 19th-century buildings with cutting-edge studios and exhibition halls. Students can often be seen sketching outdoors, staging installations, or attending critiques in well-lit studios filled with historical resonance.

With a highly selective admissions process, the academy accepts a small number of students each year, ensuring a high level of individual mentorship. Faculty are drawn from successful contemporary practitioners, many of whom are active on the international exhibition circuit. Public engagement is also central; annual exhibitions, open studios, and lectures welcome the broader community into the academy’s creative world. These events reaffirm the academy’s ongoing role in shaping not just artists, but cultural discourse.

Balancing Tradition and Innovation

Under the leadership of rectors like Prof. Ernst Caramelle, who served from 2012 to 2018, the academy made efforts to modernize its facilities and increase global partnerships. Caramelle, a respected conceptual artist, brought international visibility and strategic collaboration with institutions in Austria, Italy, and the United States. His tenure marked an era of expansion and experimentation while preserving the school’s academic rigor. Recent leadership continues this trajectory, balancing new media with classical discipline.

The Kunstakademie Karlsruhe also maintains a digital archive and online galleries, helping students build professional portfolios and connect with curators and collectors worldwide. Programs in art theory and cultural criticism supplement studio work, making students not only creators but thinkers. Despite technological shifts, the academy’s heartbeat remains the same: training artists in the tradition of Schirmer while embracing the future. It is this dual commitment that keeps Karlsruhe relevant in a world saturated with fleeting images.

Key Takeaways

- The Kunstakademie Karlsruhe was founded in 1854 by Grand Duke Friedrich I to cultivate fine arts in Baden.

- Influential artists like Johann Wilhelm Schirmer and Horst Antes shaped its academic and creative philosophy.

- The academy faced suppression under the National Socialist regime but revived strongly after World War II.

- Post-war figures like Otto Laible and Markus Lüpertz helped re-establish international prestige.

- Today, the academy blends tradition and innovation through selective admissions and diverse curricula.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who founded the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe and when?

It was founded in 1854 by Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden. - What styles were taught during the 19th century?

Romanticism and Realism were the primary styles, with an emphasis on plein air and naturalistic techniques. - How was the academy affected during the Third Reich?

Modernist professors were dismissed, and the school was forced to conform to ideological art standards. - Who are some famous alumni?

Notable alumni include Markus Lüpertz, Horst Antes, and Georg Baselitz. - What is the academy like today?

It offers diverse programs in visual arts and media, combining traditional methods with contemporary innovation.