In the heat of the French Revolution, few figures were more artistically and politically intertwined than Jacques-Louis David. Born in Paris in 1748, David became France’s leading Neoclassical painter. His early works, such as Oath of the Horatii (1784), established him as a master of classical themes, moral seriousness, and dramatic composition. But as France erupted into political violence after 1789, David shifted from mythology and history to the turmoil of his own time. By 1792, he had joined the Jacobin Club, the most radical of the revolutionary factions, aligning closely with Maximilien Robespierre. His role quickly expanded beyond the studio. In 1793, he was elected to the National Convention, and soon after, appointed to the powerful Committee of General Security.

David’s political influence gave him the means to shape the visual culture of the Revolution. He designed festivals, public funerals, and commemorative ceremonies that celebrated Revolutionary martyrs and Republican ideals. Art, to David, was not merely for beauty—it was for nation-building. He believed painting could shape public morality, reinforce civic virtue, and inspire sacrifice for the Republic. Nowhere was this belief more vividly realized than in The Death of Marat, painted in 1793, the same year Marat was murdered. This was not a commissioned work in the traditional sense. Rather, it was a tribute David undertook personally, both as an artist and as a revolutionary mourning the loss of a comrade.

A Martyr in the Bathtub

Jean-Paul Marat, born in 1743 in Boudry, Switzerland, was a trained physician, a passionate writer, and a devoted revolutionary. His newspaper L’Ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People) made him a household name during the Revolution, known for its fierce denunciations of royalists, moderates, and supposed enemies of the state. Marat suffered from a chronic skin condition, possibly dermatitis herpetiformis or a related illness, which confined him to a medicinal bath for hours each day. It was there, on July 13, 1793, that he was stabbed to death by Charlotte Corday, a young woman from Normandy aligned with the moderate Girondins. She claimed she murdered Marat to stop the violence and prevent further civil war.

His death shocked Paris. To Jacobins like David, Marat was not just a casualty—he was a martyr, a man who died for liberty and the people. The following day, David was granted permission to visit Marat’s body and sketch the scene. These sketches would form the basis for The Death of Marat, completed and publicly displayed within months. The speed and solemnity of the painting’s creation reflected not only David’s grief but his determination to enshrine Marat in the pantheon of Revolutionary heroes.

Artistic Composition and Symbolism

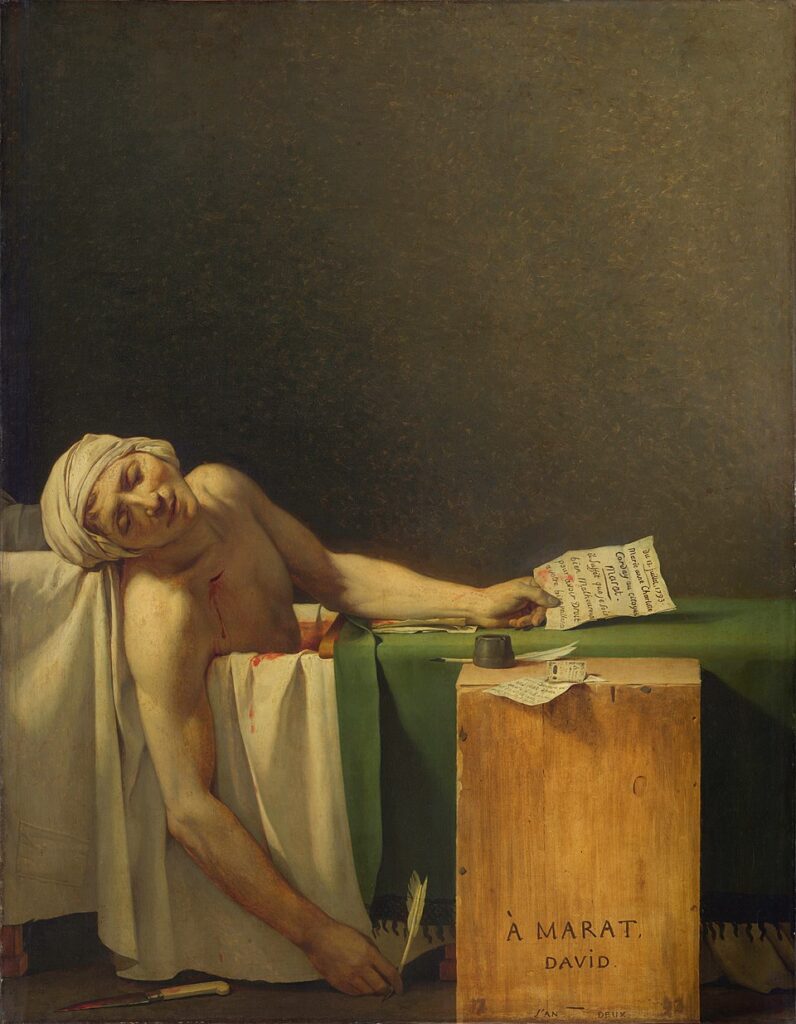

David’s painting, officially titled La Mort de Marat (The Death of Marat), was completed in late 1793. The work is oil on canvas, measuring 165 by 128 centimeters. It is housed today in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels. The composition is stark and stripped of ornament. Marat’s body lies slumped in his bathtub, one arm hanging over the side, a quill in his right hand, and a bloodied letter in the other. A wooden crate doubles as his writing desk, labeled simply “À Marat, David.” The blade and blood-stained wound are depicted with minimal gore; the calmness of his face contrasts hauntingly with the horror of his murder.

David’s artistic choices elevate Marat to a level of moral sanctity. The light falls gently across his body, highlighting his pale skin against the brown and green tones of the background. The chiaroscuro—a technique borrowed from Caravaggio—serves to dramatize the figure without indulgent sentiment. Art historians have long noted the parallels between Marat’s pose and that of Christ in many depictions of the Pietà. His left arm hangs limp in a way that recalls Michelangelo’s The Entombment of Christ. By using the visual language of Christian martyrdom, David turned Marat from a revolutionary journalist into a quasi-saint of the Republic.

The simplicity of the surroundings—the absence of decoration, the rough-hewn crate, and the torn letter—adds to the message. This was a man of the people, murdered while working in service to them. The letter in Marat’s hand, addressed from Charlotte Corday, reads: “Il suffit que je sois bien malheureuse pour avoir droit à votre bienveillance” (“Given that I am miserable, I have a right to your help”). That she used this appeal for mercy to gain access makes her betrayal more striking. For the viewer, the letter stands as a final testament to Marat’s compassion and Corday’s deception.

The Painting’s Public Role and Reception

After its completion, The Death of Marat was immediately displayed at the National Convention and soon became one of the Revolution’s most iconic images. David arranged Marat’s public funeral and had the painting installed in the hall of deliberation, effectively turning it into a shrine. It was reproduced in prints, carried through the streets, and viewed as a model of Republican sacrifice. This wasn’t merely art—it was visual propaganda, intended to stir public devotion and fear in equal measure.

Marat was portrayed as a man of pure ideals, assassinated by the forces of reaction and compromise. The Jacobins declared him “the friend of the people” and used his image to rally support for more radical policies. David’s painting was crucial in building that narrative. Yet this heroic portrayal did not survive the Revolution itself. After Robespierre was overthrown in July 1794, during the Thermidorian Reaction, Marat’s image was removed from public spaces. David himself was imprisoned for several months, narrowly escaping execution.

Though The Death of Marat was no longer politically useful to the new regime, it remained a powerful artistic statement. Even critics of the Revolution could not deny the painting’s technical skill or emotional force. Over time, its meaning would shift—from propaganda to memorial, from contemporary tribute to historical masterpiece.

David’s Final Years and the Legacy of Marat

After the fall of Robespierre, David’s political career collapsed. Though he continued to paint under Napoleon, including the vast Coronation of Napoleon (1807), he never again created a work as intimately tied to political martyrdom as The Death of Marat. In 1816, after the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, David was exiled to Brussels, where he lived until his death in 1825. Though he produced portraits and classical subjects in exile, he declined all offers to return to France, even when pardoned.

Despite changing regimes and artistic fashions, The Death of Marat endured. In the 19th century, Romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix admired its emotional intensity and precision. In the 20th century, it was reinterpreted by artists such as Pablo Picasso and even political movements that sought to harness its revolutionary iconography. Yet David’s original intention—elevating a murdered comrade into a symbol of public virtue—remains its core meaning.

Today, the painting is widely regarded as one of the finest political artworks ever created. Its power lies not only in its composition but in its sincerity. David did not romanticize the Revolution—he was one of its architects. The Death of Marat is the work of a man who believed in the ideals he painted. It is a portrait of a man, a cause, and a moment that shaped modern France.

Key Takeaways

- The Death of Marat was painted by Jacques-Louis David in 1793, shortly after Marat’s assassination.

- David was a committed Jacobin and used art as political propaganda during the French Revolution.

- The painting draws on classical and Christian symbolism to portray Marat as a martyr.

- It was originally displayed in the National Convention as part of a broader campaign to glorify the Revolution.

- Despite political backlash after Robespierre’s fall, the painting became a timeless masterpiece of political art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the dimensions and location of The Death of Marat?

It measures 165 × 128 cm and is currently housed in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels.

Why was Marat assassinated?

Jean-Paul Marat was killed by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer who believed his radicalism was fueling civil war.

Did Jacques-Louis David witness Marat’s death?

No, but he visited Marat’s body shortly after the assassination to make detailed sketches for the painting.

What is written on the letter in Marat’s hand?

It’s an appeal for help from Charlotte Corday herself, ironically used to gain access to her victim.

Was David punished after the Revolution?

Yes. He was imprisoned after Robespierre’s fall and later exiled to Brussels in 1816 following the Bourbon restoration.