Lovis Corinth was born on July 21, 1858, in Tapiau, East Prussia—now Gvardeysk, Russia. His birth name was Franz Heinrich Louis Corinth, but he later adopted “Lovis” as a more distinctive artistic signature. Raised in a Protestant middle-class household, Corinth showed an early aptitude for drawing. In 1876, he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Königsberg, where he trained under Otto Günther and Ludwig Rosenfelder. The curriculum there emphasized anatomy, shading, and narrative composition, aligning with the academic realism that dominated German painting in the late 19th century.

By 1880, Corinth moved to Munich to continue his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts under Franz Defregger and Ludwig von Löfftz. He absorbed the principles of the Munich School, known for its dark palettes and historical seriousness. However, he soon grew restless. In 1884, he traveled to Paris to enroll at the Académie Julian, where he studied under William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Though Bouguereau was famous for his polished neoclassical style, Paris exposed Corinth to new artistic possibilities, including Impressionism. He returned to Germany in 1887 with a toolkit that combined academic technique with growing curiosity about color and expression.

Transition to Berlin and Artistic Maturity

Corinth spent the next several years in Munich, exhibiting regularly but struggling to distinguish himself from his peers. Everything changed in 1901, when he moved to Berlin and joined the Berlin Secession—a group formed in 1898 by artists who rejected the rigid standards of the official academy exhibitions. In Berlin, Corinth thrived. He opened a private art school that attracted numerous students, including Charlotte Berend, who would later become his wife. His studio became a hub for Berlin’s rising modernist painters.

In 1911, Corinth became president of the Berlin Secession, following the tenure of Max Liebermann. Though Corinth shared the group’s disdain for bureaucratic control over art, his own values were rooted in discipline and tradition. That same year, he suffered a debilitating stroke that partially paralyzed the right side of his body. Remarkably, he re-trained himself to paint with his left hand and continued to produce a large volume of work. Rather than limiting him, the stroke seemed to intensify his style—his brushwork grew more energetic, his color more vivid. He remained a fixture in Berlin’s art world until his death in 1925.

Personal Life and Key Turning Points

Corinth married Charlotte Berend in 1903. She was more than a student—she became a frequent model, lifelong partner, and later, the primary custodian of his legacy. Together they had two children: Thomas, born in 1904, and Wilhelmine, born in 1909. Charlotte often appears in his domestic scenes and allegorical paintings, lending emotional warmth to much of his middle-period work. Her influence was stabilizing during the political and artistic upheavals of early 20th-century Berlin.

The stroke in 1911 marked a critical juncture in Corinth’s career. He lost some fine motor control in his dominant hand, but he adapted quickly, learning to work with his left. His style underwent a significant transformation. Earlier academic restraint gave way to bolder brushwork, simplified forms, and emotional rawness. This period also saw an increase in religious and mythological subjects, often treated with a psychological intensity unmatched in his earlier work. Corinth died on July 17, 1925, in Zandvoort, Netherlands, while traveling with his family. He is buried in the artists’ section of Waldfriedhof Stahnsdorf near Berlin.

- Key Dates in Corinth’s Career:

- 1858: Born in Tapiau, East Prussia

- 1876–1880: Studies in Königsberg and Munich

- 1884–1887: Training in Paris under Bouguereau

- 1901: Moves to Berlin; joins Berlin Secession

- 1911: Elected president of Berlin Secession; suffers stroke

- 1914: Paints Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel

- 1925: Dies in Zandvoort, Netherlands

- Influential Teachers and Peers:

- Otto Günther (Königsberg)

- Franz Defregger, Ludwig von Löfftz (Munich)

- William-Adolphe Bouguereau (Paris)

- Contemporaries: Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, Walter Leistikow

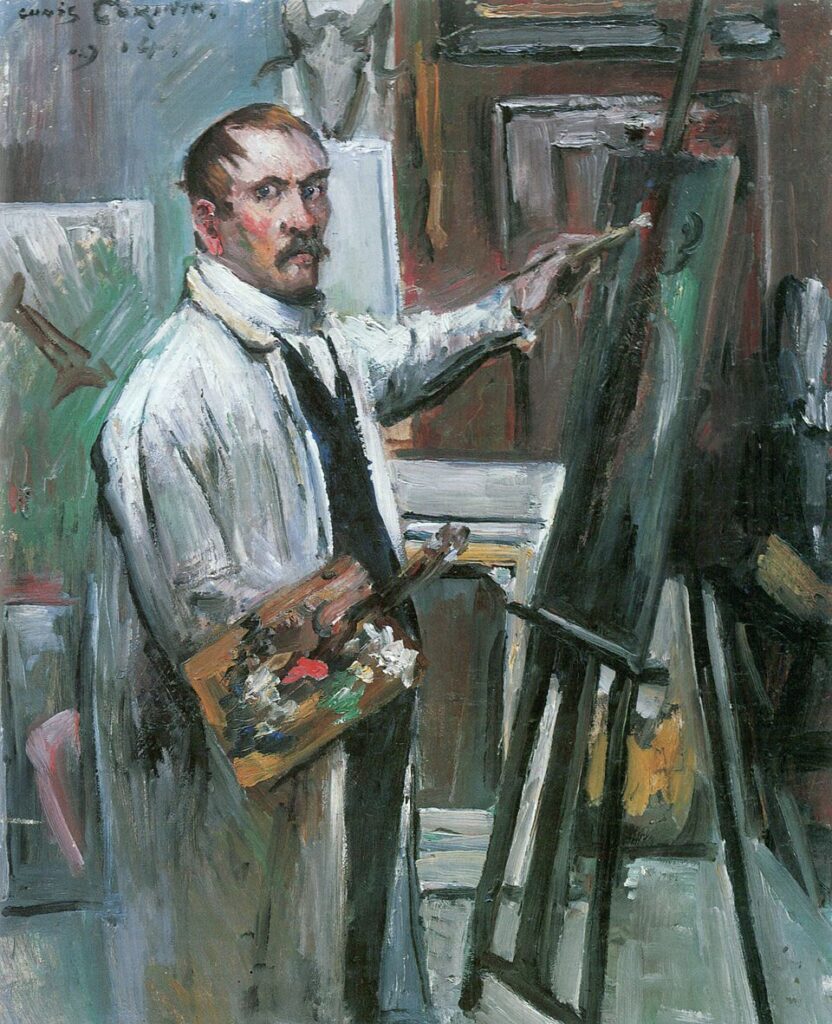

Analyzing Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel (1914)

Description of the Painting: Composition and Technique

Painted in 1914, Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel is among Lovis Corinth’s most iconic images. Executed in oil on canvas, the work measures approximately 66 by 86 centimeters and is housed today in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Corinth depicts himself standing directly before his easel, brush in his right hand and palette in the left, confronting the viewer with a stern, commanding gaze. The viewpoint is slightly below eye level, emphasizing Corinth’s physical presence and status as a master at work.

The background is intentionally vague, likely his studio, but rendered with energetic strokes rather than defined detail. The dominant colors are earthy reds, ochres, and deep browns, with Corinth’s white shirt and pale skin drawing attention to the center. The brushwork is thick and confident, characteristic of his post-stroke style. Rather than striving for photographic likeness, Corinth focused on emotional impact and painterly vigor. The result is both a portrait and a declaration: this is the artist as worker, thinker, and survivor.

Symbolism and Self-Representation in the Work

This self-portrait is not a private moment—it is a public statement. By presenting himself at the easel, Corinth claims a lineage going back to Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Courbet, artists who depicted themselves in the act of creation. But unlike those earlier examples, Corinth’s painting lacks studio props or assistants. The only visible tools are the brush and palette, reinforcing the solitary, almost heroic, image of the artist as individual creator.

Painted three years after his stroke, the portrait also functions as a testament to personal resilience. Though Corinth appears to hold the brush in his right hand in this depiction, scholars note that by this time, he was using his left due to lingering paralysis—suggesting either a mirrored view or symbolic inversion. The work conveys strength, not fragility. His unflinching stare and upright stance communicate control, masculinity, and mastery. In a time when Germany was on the brink of war, Corinth’s self-image remains tied to order, discipline, and artistic continuity.

Reception, Exhibition History, and Influence

Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel was completed during a prolific period in Corinth’s career, just before World War I disrupted the Berlin art scene. It was acquired by the Alte Nationalgalerie shortly after its completion and remains a key work in their early 20th-century collection. Though Corinth painted many self-portraits, this one has drawn consistent attention for its dramatic assertion of artistic identity.

Over time, the painting has been reproduced in major publications on German modernism and has featured prominently in exhibitions of Corinth’s work, including retrospectives at the Neue Nationalgalerie and the Lenbachhaus. Artists influenced by Corinth’s robust self-representation include Max Beckmann, who explored similar themes of creative identity in the 1920s and 30s. Even postwar German painters, such as Georg Baselitz, have cited Corinth’s fearless figuration as a model for confronting modern identity.

Corinth’s Style: Between Realism and Expressionism

Early Realist Foundations and Academic Precision

Lovis Corinth began his artistic journey rooted firmly in academic realism. His training in Königsberg and Munich emphasized traditional composition, anatomical accuracy, and narrative clarity. Early works such as Pietà (1883) and The Blinded Samson (1892) reveal his commitment to classical structure and balanced design. These paintings often depicted religious or historical themes, reflecting the conventions of the Munich School and the preferences of late 19th-century German collectors. His palette at this stage was dark and subdued, and his brushwork careful and controlled.

Even in these formative years, however, Corinth showed signs of personal style. His figures often possessed an emotional force that set them apart from the decorative or idealized images favored by his teachers. In Crucifixion (1891), for example, Corinth emphasized raw physical suffering, avoiding the sentimentality that marred similar works of the period. This commitment to emotional truth, even within academic boundaries, laid the groundwork for his later stylistic shifts. Corinth never abandoned form or structure, but he gradually expanded his toolkit to include more expressive means.

Embrace of Impressionist and Expressionist Techniques

Corinth’s style began to change during his years in Berlin, especially after his stroke in 1911. Though he had long been influenced by French painting—particularly by the atmospheric light and color effects of Impressionism—he resisted joining any formal artistic movement. After 1911, however, the combination of physical limitation and spiritual resolve transformed his technique. Brushstrokes became looser, forms more energetic, and his palette more vibrant. Critics at the time described this shift as a move toward Expressionism, though Corinth himself rejected that label.

His paintings from the 1910s and early 1920s—such as Ecce Homo (1925) and Salome (1916)—demonstrate a raw, visceral energy that had not been present in his earlier, more structured compositions. Despite these changes, Corinth’s work remained grounded in representation. He never pursued abstraction and continued to focus on the human figure. His belief in the integrity of craft and the primacy of observation remained constant, even as his methods became more forceful and emotional.

Self-Portraiture as Lifelong Practice

Few artists have explored self-portraiture with the intensity and consistency of Lovis Corinth. From the early 1880s until his death in 1925, he produced more than 60 self-portraits. These works function as a visual autobiography, documenting not only his physical appearance but also his changing artistic and emotional states. Early self-portraits tend to be confident and formally composed. By contrast, the later examples—especially those after his stroke—reveal vulnerability, defiance, and an unflinching awareness of aging and mortality.

Among the most compelling of these is Self-Portrait with Skull (1924), painted only a year before his death. In it, Corinth faces the viewer with a bare skull beside him, confronting the inevitability of death with stoic determination. Repeated themes in his self-portraits include the artist at work, direct gazes, and classical props like laurel wreaths or Greek robes. Through these motifs, Corinth presents himself not just as a painter but as a figure within the broader Western tradition—a successor to Rembrandt, yet distinctly German in temperament and style.

- Recurring Motifs in Corinth’s Self-Portraits:

- Standing at the easel

- Holding tools (brush, palette)

- Use of symbolic objects (skulls, wreaths)

- Varied expressions: stoic, proud, fatigued

- Stylistic Traits After 1911 Stroke:

- Looser, bolder brushwork

- Higher contrast in color and lighting

- More psychological intensity

- Occasional physical distortion of features

- Artistic Comparisons:

- Rembrandt: Shared introspective depth in late self-portraits

- Courbet: Assertive self-representation and realism

- Max Beckmann: Continued Corinth’s tradition of bold, existential self-imaging

Legacy of Corinth and His Self-Portraits Today

Corinth’s Place in German Art History

Lovis Corinth occupies a unique position in the history of German painting. He straddled two major epochs: the disciplined academicism of the 19th century and the expressive innovations of the early 20th. Though his contemporaries Max Liebermann and Max Slevogt are often cited as leading figures of German Impressionism, Corinth brought something distinct to the movement—greater emotional force, physicality, and psychological complexity. He rejected ideological manifestos and stylistic schools, insisting that artistic integrity came from craft, not theory.

While often categorized as an Expressionist in his later years, Corinth himself would have resisted the label. His deep respect for tradition, especially the Old Masters, set him apart from the avant-garde. Yet his influence is undeniable. His commitment to figuration and his fearless self-scrutiny paved the way for German artists of the interwar years and beyond. In particular, his legacy can be seen in the work of New Objectivity painters, who also grappled with identity, war, and the role of the artist in a changing world.

Critical and Scholarly Interpretations

Corinth’s self-portraits, especially those after 1911, have drawn considerable attention from scholars interested in masculinity, mortality, and artistic identity. German art historians have typically emphasized his technical evolution and his dedication to classical form, while more recent international scholarship has explored the psychological dimensions of his work. Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel (1914) is often interpreted as a turning point—where Corinth confronts both his disability and his determination to keep painting.

Academic interest in Corinth has increased since the 1980s, with monographs, dissertations, and curated exhibitions focusing on his self-representation and stylistic development. Critics agree that Corinth’s refusal to abandon figuration or yield to abstraction gives his work a special standing in German modernism. Unlike many of his peers, he never used art as a political or social weapon. Instead, his focus remained personal and philosophical: art as a record of life, labor, and loss.

Collecting, Exhibiting, and Viewing Corinth Today

Corinth’s works are now held in major public collections across Germany and Europe. The Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin houses some of his most iconic pieces, including the 1914 Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel. Other institutions with strong Corinth holdings include the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Museum Wiesbaden, and the Belvedere in Vienna. Retrospectives in the 2010s and 2020s have revived interest in his legacy, especially in light of renewed attention to late German Romanticism and pre-war modernism.

On the art market, Corinth’s works command high but not excessive prices—often selling well below their equivalents by French Impressionists or later German Expressionists. His widow, Charlotte Berend-Corinth, was instrumental in cataloguing and preserving his legacy, and her efforts have made his work widely available through institutional loans and digitization projects. As museums across Europe continue to re-contextualize early 20th-century art, Corinth’s place as a transitional figure—traditional in values, modern in method—has become increasingly secure.

Key Takeaways

- Lovis Corinth’s Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel (1914) was painted after his 1911 stroke and reflects his mature, expressive style.

- The painting asserts Corinth’s identity as a working artist and survivor, combining technical mastery with emotional intensity.

- Corinth’s self-portraits form one of the most comprehensive visual autobiographies in modern art history.

- His style evolved from academic realism to an expressive, psychological approach without abandoning representation.

- Today, Corinth is recognized as a key figure in the transition from 19th-century realism to 20th-century expression in German art.

FAQs

Where is Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel by Corinth located?

It is in the collection of the Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

When was Self-Portrait in Front of the Easel painted?

It was painted in 1914, three years after Corinth suffered a stroke.

Was Corinth an Expressionist?

He is often linked to Expressionism for his late style, but he did not identify with any movement and remained committed to figuration.

How many self-portraits did Corinth paint?

More than 60, spanning from the early 1880s to just before his death in 1925.

Did his stroke affect his painting style?

Yes. After his 1911 stroke, he painted with his left hand, leading to looser brushwork and more emotional expression.