The concept of the sublime became a defining force in Romanticism, shaping how artists and poets portrayed nature, emotion, and the human spirit. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Romantic thinkers and creators sought experiences beyond mere beauty, aiming for the overwhelming sensations that the sublime evokes. Romanticism itself emerged as a reaction against the rigid rationalism of the Enlightenment, favoring individual experience and emotional depth. The juxtaposition of calm beauty with overwhelming awe captured the imagination of a generation that longed for deeper meaning in a rapidly changing world.

The concept of the sublime traces its philosophical lineage back to foundational works that explored overwhelming emotional experiences. Writers such as Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant shaped early modern understanding of the sublime by distinguishing it from mere beauty and framing it as a powerful emotional encounter. Their ideas resonated with artists who felt that nature’s vastness and terror could reveal profound truths about humanity’s place in the cosmos. Romanticism embraced these insights, embedding the concept of the sublime at its heart.

Defining the Sublime

At its core, the sublime is rooted in experiences that overwhelm the senses, stirring both awe and fear with a sense of grandeur that transcends ordinary perception. Philosophers distinguished the sublime from beauty by emphasizing magnitude, power, and the emotional intensity of encountering something beyond human scale. Rather than serene appreciation, the sublime inspires trembling wonder, a dynamic tension between attraction and repulsion. This emotional richness made the concept indispensable to Romantic artists who sought to push beyond conventional aesthetics.

The Romantic era’s fascination with the sublime reshaped literature and art by privileging intense subjective experience over classical ideals of harmony and proportion. The overwhelming forces of nature, mysterious landscapes, and profound emotional states became standard themes in Romantic works. By embracing the sublime, Romanticism celebrated the individual’s inner world and its capacity for transcendence. In doing so, it opened pathways for exploring the deepest nuances of human feeling.

Philosophical Foundations of the Sublime

The philosophical foundations of the sublime lay primarily in the works of 18th‑century thinkers who dissected human emotional responses to vastness, power, and terror. Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, published in 1757, was instrumental in separating the sublime from simple aesthetic pleasure. Burke argued that experiences invoking fear and awe, such as thunderstorms or rugged mountains, could elicit the sublime when perceived safely. His emphasis on emotional intensity influenced many Romantic poets and artists who sought to evoke similar feelings in their audiences.

Immanuel Kant deepened the discussion with his 1790 Critique of Judgment, distinguishing between the mathematical and dynamical sublime. For Kant, mathematical sublimity arises from contemplating vastness beyond human comprehension, while dynamical sublimity stems from forces of nature that overpower our senses. Both forms elevated the observer’s sense of reason and moral freedom, according to his philosophy. These ideas resonated with Romantic creators who saw in the sublime a way to explore human transcendence over nature’s overwhelming power.

The Romantic movement adopted these philosophical insights and applied them to literature, painting, and music as a means to express intense emotional and spiritual experience. Burke and Kant did not work as artists, yet their theories gave Romanticism intellectual grounding for valuing emotional response over classical restraint. The concept of the sublime thus became a bridge between Enlightenment thought and Romantic expression. It provided a language for artists to articulate encounters with forces beyond human control.

Romantic philosophers and practitioners saw the concept of the sublime as a challenge to Enlightenment rationality, inviting emotional depth and spiritual inquiry. In contrast to the calm and ordered beauty prized by neoclassicism, the sublime invited tumult, power, and mystery. This shift aligned with Romanticism’s broader cultural movement toward emphasizing individual sensation and imagination. In this way, philosophical foundations powered the Romantic embrace of the sublime.

The Sublime in English Romantic Poetry

English Romantic poetry stands as one of the richest domains where the concept of the sublime shaped literary expression in vivid and lasting ways. Poets such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley infused their verse with encounters that startled the senses and stirred deep emotion. Their works embraced vast landscapes, supernatural mystery, and inner reflection as vehicles for sublime experience. These contributions reflected both personal journeys and the broader Romantic pursuit of emotional depth.

William Wordsworth, born in 1770 and educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge, wrote poetry where nature’s quiet power became a source of spiritual renewal. In Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey (1798), the winding river and towering trees evoke profound contemplation that transcends simple beauty. Wordsworth’s emphasis on memory and reflection invited readers to engage with nature’s vast presence as a reflection of the inner self. His poetic voice helped anchor the sublime as an emotional and philosophical touchstone of Romantic literature.

Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, born in 1772, collaborated with Wordsworth on the seminal 1798 Lyrical Ballads, a work that helped define English Romantic poetry. In The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Coleridge used supernatural and sea imagery to plunge readers into terror and wonder, a poetic embodiment of the sublime. Percy Bysshe Shelley, born in 1792, explored similar themes in poems like Mont Blanc, where the mountain’s daunting scale becomes a metaphor for the mind’s infinite capacities. Shelley’s work bridged sensory perception and idealistic thought, deepening the Romantic sublime’s philosophical reach.

Coleridge and Shelley maintained friendships and intellectual exchanges that influenced their poetic explorations of the sublime. Coleridge’s deep interest in German philosophy further enriched his poetic imagination, adding layers of metaphysical inquiry to his work. Shelley’s radical idealism and poetic brilliance inspired later generations of poets and thinkers. Together, these figures demonstrated how the concept of the sublime could be woven into literature as a profound, multi‑layered experience.

The English Romantics’ use of the sublime extended beyond mere depiction of landscape; it became a way to unify emotion, nature, and imagination. Their poetry invited readers to confront the magnitude of the natural world and, in doing so, to question their own inner depths. Through their passionate verse, Romantic poetry made the sublime a central pillar of literary expression. The legacy of this engagement continues to shape how literature explores human feeling and the natural world.

Visual Arts and the Sublime in Romanticism

In visual art, the concept of the sublime transformed landscapes and natural forces into symbols of emotional and spiritual intensity. Romantic painters rejected classical order and idealized proportion, instead seeking scenes that conveyed overwhelming scale and power. Through sweeping vistas, tumultuous weather, and evocative light, artists captured the sublime’s emotional resonance. Their work invited viewers to feel the majesty and terror of nature as a reflection of human longing and frailty.

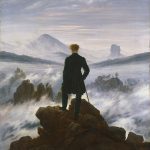

Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner

Caspar David Friedrich, born in 1774 in Greifswald, became a central figure in German Romantic painting whose landscapes embody the sublime’s introspective power. Works such as Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) portray solitary figures facing immense natural vistas, evoking both awe and introspection. Friedrich’s use of misty mountains and vast seas invited viewers to contemplate the infinite, blending external nature with inner reflection. His art became a visual manifesto for Romanticism’s emotional engagement with landscape.

J.M.W. Turner, born in 1775 in London, brought the sublime to life with bold brushwork and dramatic lighting that captured nature’s raw energy. In paintings such as Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps (1812), Turner conveyed the blinding force of wind and snow, immersing viewers in sensory tumult. His fascination with light, sea storms, and fiery sunsets communicated a turbulent, almost elemental sublime that pushed the boundaries of traditional landscape painting. Turner’s work, forward‑looking and expressive, helped pave the way for later movements in modern art.

Other Romantic painters such as John Constable and Théodore Géricault also embraced the sublime, though in diverse ways that reflected their personal visions. Constable’s skies and fields conveyed a quieter but still powerful sense of nature’s presence, while Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) used human suffering amidst vast sea to confront existential terror. Together, these artists expanded the artistic language of the sublime from serene contemplation to visceral immersion. Their contributions ensured that Romanticism’s visual arts would forever be linked to the emotional depth of the sublime.

The influence of sublime aesthetics extended beyond individual masterpieces to shape broader artistic movements across Europe. Romantic artists shared networks and exhibitions that spread ideas about nature, emotion, and scale. Their works invited viewers not just to observe but to feel, embodying the Romantic belief in art’s capacity to move the soul. In this way, the concept of the sublime became integral to Romantic visual expression.

Nature as a Vessel for the Sublime

Nature became the indispensable vessel through which Romantic creators channelled the concept of the sublime, presenting landscapes that invoked both awe and introspection. Romanticism emerged during a period of scientific discovery and exploration, when mountains, oceans, and skies were newly framed as sites of mystery and power. For poets and painters alike, natural phenomena such as storms, cliffs, and endless horizons offered sensory experiences beyond ordinary human comprehension. These scenes transcended mere scenic beauty to evoke emotional intensity that stirred the imagination.

Remote mountain ranges like the Alps and the Highlands became recurring motifs in Romantic art and literature, representing both physical grandeur and inner psychological depth. Writers and artists traveled to these rugged terrains in search of profound encounters with nature’s scale. The towering peaks, plunging valleys, and echoing silence fostered a sense of human smallness before unbounded magnitude. These experiences shaped works that emphasized the sublime’s capacity to challenge and expand human perception.

Storms at sea and tumultuous waters likewise served as powerful symbols of the sublime in Romantic works. The sea’s relentless motion, crashing waves, and shifting light provided a dramatic backdrop for narratives of struggle and reflection. Romantic artists used these marine scenes to explore tension between awe and fear, inviting audiences to confront the raw forces of nature. In such depictions, nature’s beauty becomes inseparable from its capacity to unsettle and overwhelm.

Mountains, storms, and seascapes also echoed contemporary scientific interests in geology, meteorology, and exploration. Romantic creators embraced these fields’ discoveries while maintaining a deep‑rooted sense that nature’s mysteries eluded total rational explanation. Their works suggested that emotional and spiritual insight could arise from encounters with nature’s vast and sometimes terrifying presence. In this respect, nature served as both inspiration and stage for the sublime.

The Sublime and the Individual Experience

Central to Romanticism’s appeal was the belief that the concept of the sublime could unlock deep individual experience, weaving together solitude, imagination, and emotional intensity. Romantic thinkers valued the solitary figure confronting nature, a motif that symbolized personal reflection and inner transformation. This emphasis on subjectivity marked a departure from earlier artistic traditions that privileged social order and classical harmony. For Romantics, the path to truth often passed through intense emotional engagement with the world’s vastness.

In literature and painting, solitude was not portrayed as loneliness but as a space for heightened awareness and self‑discovery. Characters and figures confronted storms, cliffs, and seas not merely as backdrops but as catalysts for personal insight. The interplay between individual consciousness and overwhelming natural forces revealed deep layers of human feeling, from wonder to fear to reverence. This focus on the individual’s psychological journey became a hallmark of Romantic artistic expression.

Imagination played a crucial role in mediating experiences of the sublime, enabling creators and audiences to bridge the gap between sensory perception and inner meaning. Romantic artists believed that imagination allowed humans to grasp the emotional essence of vast landscapes and sublime forces. This imaginative engagement transformed natural scenes into profound reflections on existence and purpose. In so doing, Romanticism celebrated imagination as a faculty that elevated human experience beyond mere rational observation.

Emotional intensity blossomed in Romantic works as creators pursued authenticity and depth in representing the human condition. Encounters with the sublime stirred feelings that could not be neatly categorized, encompassing wonder, dread, joy, and reverence. This emotional spectrum became central to Romanticism’s enduring appeal, inviting audiences to embrace complexity and depth of feeling. Through the individual experience of the sublime, Romantic art fostered a richer understanding of human nature.

Legacy of the Sublime in Romanticism

The legacy of the concept of the sublime in Romanticism extends far beyond its own historical moment, influencing later artistic and intellectual movements that sought to capture profound emotional experience. In the 19th century, American Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) drew on Romantic ideas about nature and the inner self. Their writings explored nature as a source of spiritual insight, echoing Romantic engagements with vast landscapes and emotional depth. This intellectual lineage helped shape modern conceptions of nature and individuality.

Romanticism’s embrace of the sublime also left its mark on the Gothic revival and Pre‑Raphaelite movements in visual art and literature. Artists and writers in these traditions continued to explore dramatic emotion, intense imagery, and mysterious landscapes that challenged conventional aesthetics. The sublime’s influence thus persisted in works that valued sensory immersion and psychological complexity. Through these movements, Romantic ideals extended into diverse artistic expressions throughout the 19th century.

The concept of the sublime continues to resonate in contemporary culture, from literature and visual arts to film and music, where creators seek to evoke overwhelming emotional responses. Modern narratives often draw on the tension between beauty and terror, echoing Romanticism’s foundational insights. This enduring relevance underscores the concept’s capacity to articulate experiences that transcend simple categorization. In doing so, Romanticism’s legacy endures as a vital force in creative expression.

Ultimately, the concept of the sublime shaped Romanticism by providing a framework for exploring emotional depth, nature’s power, and individual consciousness. It bridged philosophical inquiry and artistic innovation, fostering a cultural movement that prized intensity and imagination. The Romantic sublime transformed how creators represented the world and how audiences understood their own inner landscapes. Its legacy remains woven into the fabric of artistic endeavor and human reflection.

Key Takeaways

- The concept of the sublime drove Romanticism’s focus on emotional intensity and profound experience.

- Philosophers such as Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant shaped early modern views of the sublime.

- English Romantic poets used nature and imagination to express the sublime in verse.

- Visual artists like Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner translated the sublime into dramatic imagery.

- Romanticism’s legacy lives on in later movements and contemporary explorations of emotional depth.

FAQs

- What is the “concept of the sublime”?

It is a philosophical idea describing overwhelming experiences that evoke awe, terror, and grandeur beyond ordinary beauty. - Who were major Romantic poets influenced by the sublime?

William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley are key figures who integrated sublime themes. - How did Romantic painters depict the sublime?

Artists like Friedrich and Turner used vast landscapes, dramatic weather, and emotional lighting to embody the sublime. - Why did Romanticism value nature so highly?

Nature’s scale and power offered a sensory gateway to emotional and spiritual insight. - Does the concept of the sublime still matter today?

Yes, its influence persists in modern art, literature, and cultural expressions of overwhelming experience.