The Baroque period, stretching roughly from 1600 to 1750 AD, was a time of remarkable creativity and cultural expansion in Europe. It was an era defined by grandeur, emotional intensity, and an unrelenting pursuit of beauty in both sound and sight. Whether through soaring church ceilings painted with biblical visions or the rich harmonies of sacred music, the Baroque world sought to overwhelm the senses and stir the soul. Behind the ornate expressions of the age were deep spiritual, political, and intellectual forces shaping the direction of art and music alike.

This period coincided with powerful movements like the Counter-Reformation and the rise of absolutist monarchies. The Catholic Church, in reaction to Protestant reformers, used art and music to reaffirm its authority and captivate the faithful. At the same time, kings and princes employed court musicians and painters to glorify their reigns, asserting divine favor through sensory splendor. Art and music became instruments of persuasion, enchantment, and control — wielded in cathedrals, palaces, and public squares.

Defining Baroque Aesthetics

Both visual artists and composers during this time favored drama, contrast, and movement. In painting, this meant stark contrasts between light and dark, dynamic poses, and emotionally charged subjects. In music, it meant bold shifts in tempo, ornate melodies, and layered textures that mimicked the complexity of the human heart. Whether sculpted in marble or expressed through the pipe organ, the Baroque style invited its audience into a world where heaven touched earth.

Artists and composers of the Baroque period didn’t aim for subtlety; they aimed for awe. Their works were designed to communicate power and provoke a reaction. That reaction could be religious fervor, tearful repentance, patriotic pride, or simple amazement. The result was a culture where the arts were not merely entertainment — they were tools for expressing absolute truth, divine order, and earthly glory.

Common Ground — Themes and Symbols Shared by Baroque Art and Music

Baroque art and music shared a rich symbolic language rooted in Christianity, ancient mythology, and allegory. Religious fervor was at the center of both disciplines, with the Catholic Church as a major patron. Paintings and oratorios alike portrayed saints, martyrs, and angels in moments of passion, struggle, or ecstasy. The same biblical story could appear in a fresco above the altar and in a motet sung beneath it.

In addition to sacred subjects, both music and painting often used allegory to convey moral lessons. A composer might set a parable to music in the form of a sacred cantata, while a painter illustrated the same theme through a classical myth or personification. Abstract virtues like justice, fortitude, and charity appeared frequently in both forms. Baroque artists and musicians aimed to instruct and move their audiences, not just to delight them.

Theatricality as a Unifying Principle

One of the strongest links between Baroque music and visual art was their mutual love of theatricality. Sculptors like Gian Lorenzo Bernini crafted works that seemed to move before the viewer’s eyes — none more striking than his Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–52), where the saint swoons in a rapture of divine love. At the same time, composers of sacred and operatic music constructed elaborate musical scenes full of emotion, suspense, and divine intervention.

The influence of theater on the arts can’t be overstated during this time. Even in church, art and music were arranged to create a kind of sacred drama, leading the worshipper step by step toward spiritual climax. Music swelled at key moments in Mass, while painted angels hovered above, reinforcing the message from the pulpit. This theatrical fusion elevated both music and visual art to powerful emotional experiences.

Influential Figures — Artists and Composers Who Defined the Era

Several towering figures helped shape the Baroque period and left a legacy still admired today. Among visual artists, Caravaggio (1571–1610 AD) brought intense realism and chiaroscuro to sacred subjects, casting biblical scenes in stark light and deep shadow. Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1656 AD), one of the first prominent female painters in Europe, depicted strong heroines with emotional depth, often from the Old Testament. In sculpture and architecture, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680 AD) embodied the spirit of the age with dynamic movement and spiritual intensity.

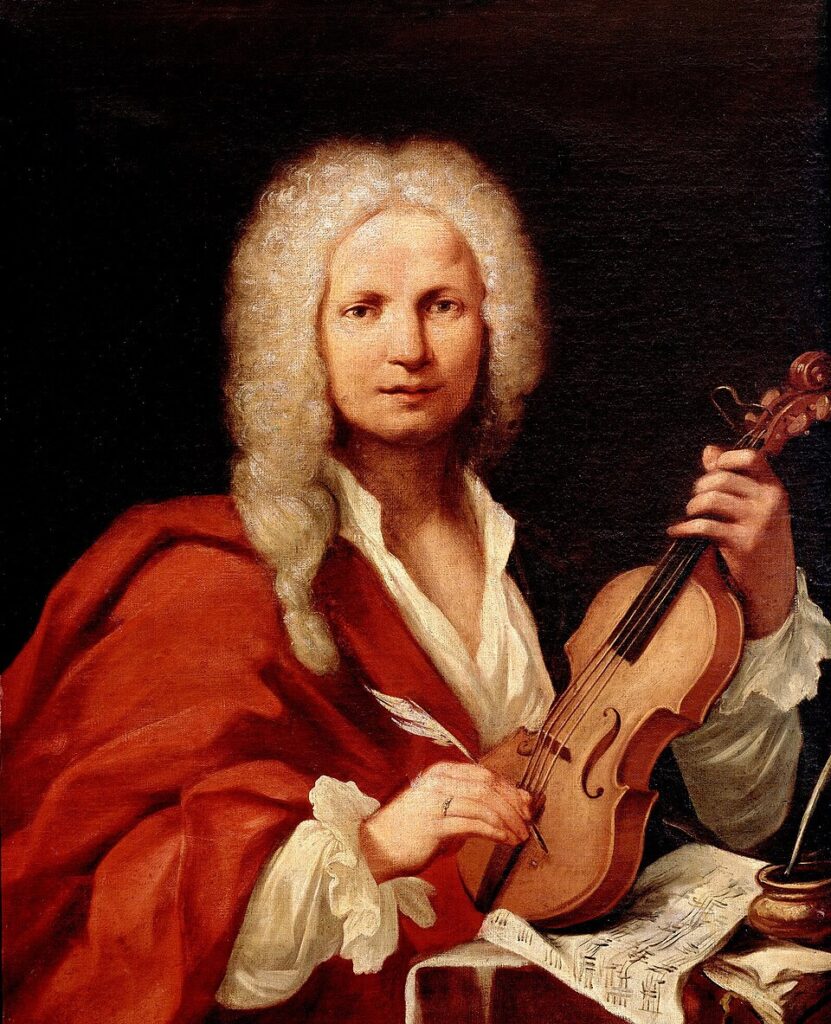

In the world of music, several composers stood at the pinnacle of achievement. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750 AD) wrote intricate fugues, passionate cantatas, and monumental organ works rooted in his Lutheran faith. George Frideric Handel (1685–1759 AD), born the same year as Bach, excelled in opera and sacred oratorio, with Messiah (1741) remaining one of the most frequently performed pieces in Western music. Earlier in the century, Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643 AD) pioneered the development of opera, blending Renaissance polyphony with the drama of the Baroque.

Overlapping Patronage and Courts

Many of these artists and composers worked under the same powerful patrons or moved through overlapping cultural centers. The Medici family of Florence, Pope Urban VIII, the Habsburgs in Austria, and Louis XIV of France all funded both visual and musical endeavors. These commissions weren’t purely aesthetic; they reinforced political and spiritual power. Artists and musicians often moved from court to court, building networks and influencing each other across national boundaries.

The court of Versailles under Louis XIV, who reigned from 1643 to 1715 AD, stands as a prime example of unified artistic vision. Painters, architects, composers, and dancers all served the king’s theatrical vision of divine rule. Jean-Baptiste Lully, the king’s favorite composer, was as central to the French Baroque as Charles Le Brun was to its visual identity. In Rome, Bernini’s collaborations with popes mirrored the way composers like Corelli wrote concerti for Church celebrations.

Sacred Spaces — How Churches United Sound and Image

Baroque churches were built to be immersive, spiritual experiences. The interplay of soaring architecture, radiant altarpieces, and soaring music aimed to transport the faithful beyond the mundane. Spaces such as the Church of the Gesù in Rome or St. Nicholas Church in Prague combined sculpture, fresco, and organ music in a unified program of devotion. The viewer and listener were not passive observers but participants in a cosmic drama.

Within these churches, music wasn’t merely background. It punctuated the liturgy, responded to Scripture, and emphasized theological messages through harmonic movement and emotional melodies. Choirs, organs, and ensembles were often placed high above the congregation, their sound cascading down to fill every crevice of the architectural space. Just as paintings climbed columns and filled domes, music extended vertically and enveloped listeners from above.

The Jesuit Influence

The Jesuit Order, founded in 1540 AD, played a pivotal role in the Baroque union of art and music. Their churches were among the most elaborately decorated and musically active in Europe. Jesuits believed in persuasion through the senses and used every available artistic tool to move their congregations toward deeper faith. Their influence can be seen in cities like Rome, Antwerp, and Vienna, where music and image served their catechetical goals.

Jesuit schools and missions also trained generations of artists and musicians, spreading the Baroque style across continents. In Spanish America, for example, native artisans and European-trained musicians collaborated in missions that produced uniquely hybrid Baroque expressions. The combination of elaborate retablos, painted ceilings, and polyphonic masses was more than decorative—it was doctrinal. In Jesuit hands, the arts became catechism in action.

Opera and Stagecraft — The Ultimate Baroque Fusion

Opera, emerging at the dawn of the Baroque period, was perhaps the most perfect blend of visual art and music. The first recognized opera, Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, premiered in 1607 AD in Mantua. This new genre combined instrumental music, vocal solos, poetry, dance, costumes, and set design into one immersive performance. Opera was more than entertainment—it was an aristocratic spectacle that demonstrated cultural and political power.

The grandeur of Baroque opera productions often rivaled that of palaces or cathedrals. Painted backdrops created the illusion of cities or heavens, while elaborate costumes conveyed mythological or historical themes. Composers used musical devices like recitative and aria to mirror dramatic emotions, while visual artists staged scenes with symbolic props and dramatic lighting. This visual-musical collaboration brought stories to life in ways neither medium could achieve alone.

Visual Artists Designing Stage Sets

Baroque visual artists frequently worked as set designers, using their understanding of perspective and form to create illusions on stage. Ferdinando Galli-Bibiena (1657–1743 AD), a member of a family of painters and architects, developed the “angled perspective” stage, creating a deeper sense of space. His designs transformed simple theaters into enchanted worlds, extending visual spectacle far beyond the proscenium.

Stagecraft during this period was deeply tied to architecture and painting. Machines were invented to change scenes rapidly or simulate weather effects. Scenes of Mount Olympus or the underworld could unfold before the audience’s eyes, supported by music that underscored the drama. This theatrical blending of sound and vision was Baroque synthesis at its most thrilling.

Secular Patronage and Artistic Innovation

While the Church remained a powerful patron, secular rulers and aristocrats also drove Baroque innovation. Kings, queens, and nobles funded grand projects that showcased their lineage, piety, and taste. Louis XIV of France (1638–1715 AD) was the most famous of these patrons, commissioning elaborate court ballets, fountains, murals, and musical performances. His palace at Versailles, begun in the 1660s, became a theater of power, with every element—from ceiling frescoes to harpsichord music—reinforcing his divine right to rule.

Beyond France, secular patronage thrived in Italy, the German states, and England. Nobles employed court composers, often supporting them for decades. Painters were commissioned to immortalize royal hunts, mythological tales, or historical victories. Both arts flourished in festivals, banquets, and parades, where the music and imagery were carefully coordinated to awe and inspire. This era saw the rise of national styles that reflected the character of each court.

Music and Art as Political Tools

The arts served political ends as well as aesthetic ones. Whether on canvas or in oratorio, imagery and sound glorified rulers, sanctified dynasties, and justified wars. Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, completed in 1684 AD, was not only an architectural marvel but a setting for royal ceremonies scored by Jean-Baptiste Lully’s compositions. Every visual and musical element reinforced a single narrative: the king as God’s chosen ruler.

This use of art and music as propaganda was effective and intentional. Paintings of rulers in heroic poses, operas praising national heroes, and musical performances marking political events helped shape public perception. Artists and composers were not merely creators but participants in the machinery of statecraft. In the Baroque worldview, beauty and power walked hand in hand.

Legacy — Lasting Impact of Baroque Synthesis

The end of the Baroque period in the mid-1700s did not bring its influence to a halt. On the contrary, many of its ideas carried into the Classical period and beyond. Composers like Haydn and Mozart inherited Baroque counterpoint and ornamentation, refining it into the balanced forms of the Classical era. In visual art, the Rococo style extended Baroque’s opulence into more playful territory before giving way to Neoclassicism.

Baroque architecture and music remain deeply admired today, with many churches still using Baroque organs and artwork. Pieces by Bach, Vivaldi, and Handel fill modern concert halls and churches alike. Bernini’s sculptures draw crowds in Rome just as Handel’s Messiah draws crowds in December. The emotional richness and spiritual power of the Baroque continue to resonate.

Baroque in Today’s Culture

The influence of the Baroque can even be seen in modern media. Filmmakers borrow Baroque lighting and design to evoke grandeur and emotion. Contemporary stage designers recreate Baroque-style sets for operas and plays. Museums regularly mount Baroque exhibitions, and new recordings of Baroque music feature historically informed performance techniques.

Why does Baroque art and music still connect with audiences centuries later? Perhaps it’s because it speaks to something permanent in human nature — the desire for beauty, truth, and transcendence. Through its grandeur, discipline, and depth, the Baroque reminds us of our longing for the eternal, conveyed through craftsmanship that endures.

Key Takeaways

- The Baroque period (1600–1750 AD) fused music and visual art through shared themes of drama, emotion, and grandeur.

- Major figures like Caravaggio, Bernini, Bach, and Handel shaped the era with innovations in style and technique.

- Churches used art and music to inspire devotion, especially under the influence of the Jesuits.

- Opera served as the most complete Baroque art form, uniting sound, vision, and story.

- Baroque legacy lives on in modern music, art, film, and architecture.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What defines Baroque art and music?

Baroque works emphasize contrast, emotion, movement, and ornate detail in both sound and sight. - Who were major Baroque composers and artists?

Key figures include Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Caravaggio, Bernini, and Artemisia Gentileschi. - How did the Church influence Baroque art?

Through commissions and doctrine, especially during the Counter-Reformation, churches shaped Baroque style toward awe and devotion. - What role did opera play in the Baroque period?

Opera was a new, immersive genre combining music, set design, costumes, and theatrical storytelling. - Why is Baroque still relevant today?

Its emotional power, craftsmanship, and spiritual depth continue to inspire audiences and artists alike.