The fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel, published in 1812 by the Brothers Grimm, has become one of the most widely illustrated stories in the Western world. Children may remember it for its fearsome witch and the enchanting gingerbread house, while scholars note its roots in darker realities of hunger. The visual appeal of the story has inspired countless artists, each layering on new meanings through line, color, and atmosphere. The tale’s endurance rests on this fusion of oral tradition, historical trauma, and artistic imagination.

Art has always been the bridge between storytelling and cultural memory. From early woodcut illustrations in printed fairy tale books to the lush plates of 19th- and 20th-century editions, the imagery of Hansel and Gretel has been central to its survival. Artists could emphasize innocence, terror, or temptation depending on cultural mood. This range makes the tale one of the richest case studies in how art preserves folklore.

Why Hansel and Gretel Endures

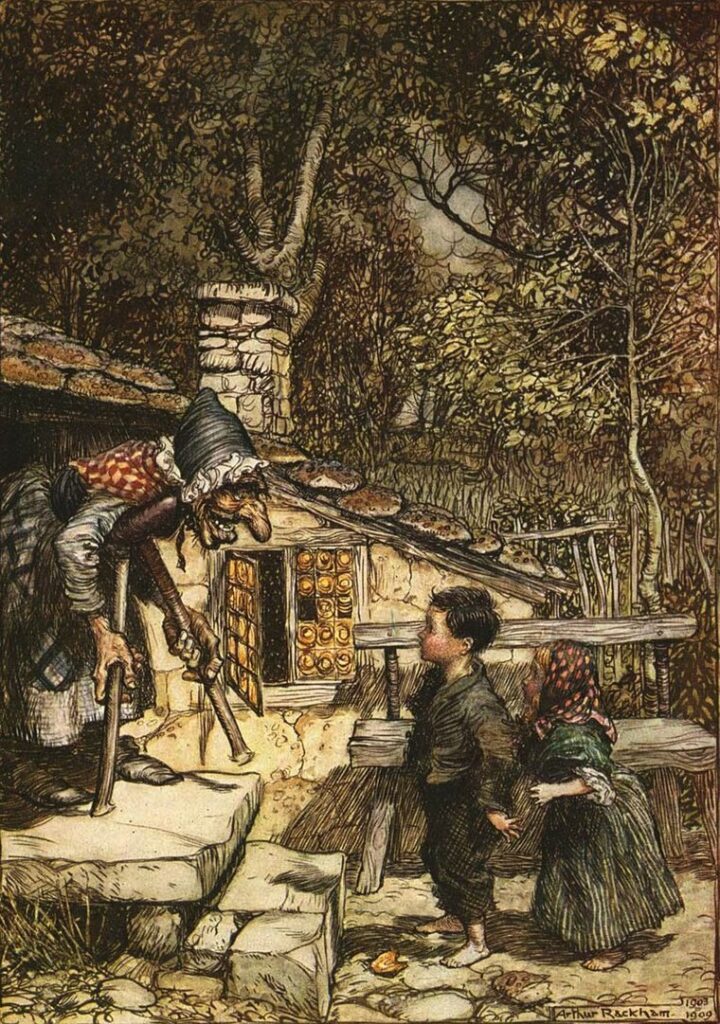

The story survives because it balances extremes: childhood innocence with adult fears, abundance with deprivation, and the safety of home with the menace of wilderness. Artists seized upon these contrasts, creating works that terrified and fascinated their audiences. The gingerbread house glistening with sugar in Arthur Rackham’s 1909 edition is both dream and nightmare. Such images fix the story in memory, ensuring it continues to speak across generations.

Without its artistic afterlife, Hansel and Gretel might have remained an obscure peasant tale. Instead, the combination of historical resonance and vivid illustration elevated it into cultural permanence. This is the power of art as a vessel for both beauty and historical remembrance. The famine-haunted story thus became an artistic legacy.

The Great Famine of 1315–1317: Europe in Crisis

The Great Famine, stretching from 1315 to 1317, plunged much of Europe into starvation. Chroniclers recorded incessant rains that rotted crops and destroyed grain supplies, while livestock perished in the mud. Manuscript illustrations such as those in the Holkham Bible (c. 1320s) show skeletal peasants and failed harvests, offering grim evidence of how artists captured the crisis. In these works, we see the historical soil from which stories like Hansel and Gretel could grow.

Hunger warped family life, and parents sometimes abandoned children when food became impossible to provide. Art from the 14th century frequently depicted gaunt figures, their ribs showing, their hands extended in supplication. Such images of famine and despair remind us of the psychological atmosphere in which fairy tales of abandonment took shape. The witch of the story can be understood as a distorted reflection of these survival fears.

Famine, Abandonment, and Survival

Even the wealthy could not entirely escape the famine’s grip, though they often commissioned devotional art seeking divine aid. In contrast, peasants left behind crude drawings, marginal doodles, and oral tales reflecting hunger directly. The art and folklore of the era both testify to the same truth: starvation shaped cultural imagination. Hansel and Gretel, with its abandoned children and hunger-driven plot, channels this legacy.

By 1322, much of Europe recovered, but the famine’s imagery lingered. Sculptures on church portals and stained-glass cycles reminded viewers of hardship. Oral storytellers carried those memories forward, while visual artists embedded them into religious and secular works. This layering of historical art and narrative eventually crystallized in the tale preserved by the Grimms centuries later.

Origins of Hansel and Gretel in Oral Tradition

The roots of Hansel and Gretel lie in centuries of oral storytelling across German-speaking lands. Tales of children lost, witches lurking in the forest, and homes made of food were whispered by firelight long before they reached print. Storytelling was itself an art, using rhythm and imagery to create mental pictures. When collected, these tales carried both the historical and the artistic imagination of common people.

Jacob Grimm (1785–1863) and Wilhelm Grimm (1786–1859) transformed this oral tradition into literature. Trained at the University of Marburg, they shifted from law to philology, devoting themselves to preserving folklore. They published the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1812, with Hansel and Gretel among its most striking tales. Their scholarship, rooted in academic rigor, was also inseparable from the artistic contributions of illustrators.

From Folklore to the Brothers Grimm

The Grimms worked with artists from the beginning, including their younger brother Ludwig Emil Grimm (1790–1863), who created woodcut illustrations. These images gave physical form to stories that previously lived only in imagination. As later editions of the Grimms’ tales expanded, more illustrators contributed, each shaping how readers pictured witches, forests, and children. The transition from oral to written tradition was also a transition from sound to sight.

Through partnerships with publishers and illustrators, the Grimms elevated folklore into a new art form. They recognized that words alone could not fully preserve the sensory power of the tales. By fusing text with image, they guaranteed Hansel and Gretel would be remembered not only in words but in haunting, enduring pictures. This combination was vital for its continued popularity.

The Forest and the House: Symbols of Fear and Desire

The forest of Hansel and Gretel is not simply a backdrop. In medieval and Renaissance art, forests were often rendered as dark, tangled masses, symbols of both mystery and exile. Artists highlighted the density of trees, often exaggerating their twisted forms to suggest menace. This echoes the fears of famine refugees forced into the woods when villages could no longer sustain them.

The gingerbread house is the other great visual symbol. Painters and illustrators seized upon its glittering surfaces of bread, sugar, and cake. For children in the 19th century, such an image was enchanting, yet it always carried the shadow of peril. The house stands as one of the most visually distinctive motifs in European folklore art.

The Allure and Danger of Shelter

Arthur Rackham’s illustrations, with their spindly trees and eerie architecture, gave the house a sinister tone. Kay Nielsen (1886–1957), working in the early 20th century, emphasized ornamental beauty with jewel-like colors, transforming the house into a dazzling trap. Each artist drew out a different side of the symbol, reflecting cultural preoccupations of their times. The duality of abundance and danger fascinated illustrators as much as readers.

In manuscripts and later engravings, houses of plenty often collapse into ruin or reveal hidden dangers. This theme connects the gingerbread house to a broader tradition of visual allegories about false security. By emphasizing both desire and deception, artists remind us that art can capture the lessons of survival as effectively as words. The forest and the house remain two of folklore’s richest visual images.

Artistic Depictions of Hansel and Gretel

The 19th and early 20th centuries were the golden age of Hansel and Gretel illustration. Ludwig Richter (1803–1884) emphasized moral clarity, while Gustave Doré (1832–1883) infused the story with dramatic contrasts of light and shadow. Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) pushed the imagery toward Gothic unease, his twisted trees almost alive with menace. These artists ensured the tale carried visual gravitas equal to its narrative weight.

In 1893, Engelbert Humperdinck’s opera Hansel und Gretel premiered in Weimar. The staging featured elaborate set designs of the witch’s cottage and the enchanted forest. Costumes, lighting, and scenic art transformed the tale into a Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” uniting music and image. The opera remains one of the most artistically ambitious retellings of any fairy tale.

Illustrators, Painters, and Stage Designers

Kay Nielsen brought Hansel and Gretel into the Art Nouveau world with his stylized figures and decorative flourishes. In Russia, Ivan Bilibin (1876–1942) illustrated similar folk tales, showing how visual traditions crossed borders. In the 20th century, picture book illustrators such as Paul Galdone softened the imagery for younger readers, but the underlying motifs remained. Each generation of artists added a new layer to the tale’s visual identity.

The collaboration of writers, illustrators, stage designers, and publishers formed a unique artistic network. Without these visual interpretations, Hansel and Gretel might have remained a mere curiosity of folklore. Instead, it became one of the most illustrated, staged, and reinterpreted stories in European art. The witches, forests, and gingerbread houses survive as much through line and color as through words.

The Tale in Broader Cultural Memory

The themes of hunger, abandonment, and temptation appear across European folklore. French, Italian, and Scandinavian traditions all preserved stories with children lost in forests or lured into peril. Artists illustrated these tales with equal vigor, often depicting grotesque ogres, witches, or monstrous figures. This repetition across visual traditions suggests a shared European trauma made visible through art.

Cannibalism, as horrifying as it is, appears in both text and image. Early woodcuts and engravings sometimes hinted at devouring monsters or witches with cooking pots. These images transformed taboo subjects into visual metaphors, much as Hansel and Gretel did in narrative form. The story’s art and folklore reinforce each other, doubling the impact on cultural memory.

Parallels with Other European Stories

Similarities can be seen in French depictions of “Hop o’ My Thumb” or Italian illustrations of famine tales. Scandinavian artists portrayed witches lurking in snowy forests, drawing on their own environmental hardships. The persistence of these motifs across borders shows how famine-inspired imagery became part of a shared European vocabulary. Visual art ensured that these lessons of survival crossed time and geography.

Comparing Hansel and Gretel to its European cousins reveals how collective imagination works. The abandoned child, the threatening adult, and the deceptive home are not isolated motifs but part of a pan-European artistic language. By studying the art of these tales, we uncover the shared legacy of famine and fear. Each drawing, engraving, or painting testifies to memory preserved through craft.

Enduring Power: Hansel and Gretel in Modern Imagination

Even today, Hansel and Gretel inspires artists across media. Contemporary illustrators reinterpret the tale in picture books with bold colors or minimalist designs. Filmmakers create visual retellings, often leaning on horror imagery to emphasize the witch and the haunted forest. The tale’s visual language remains flexible, adapting to cultural moods and artistic fashions.

In the 20th century, artists such as Maurice Sendak acknowledged the Grimms as formative influences. Exhibitions in museums have featured Hansel and Gretel illustrations alongside other fairy tales, highlighting their impact on art history. Contemporary sculptors have even built installations of gingerbread houses, blurring the line between food, art, and folklore. These modern works show the tale’s enduring vitality.

From Grim History to Modern Retelling

Films often rely on the atmospheric elements of the story: twisted forests, decrepit houses, and sinister ovens. Set designers and cinematographers continue the tradition established by Rackham and Nielsen, using light, shadow, and space to amplify fear. Modern illustrators also reinterpret the tale for new generations, often softening the witch but preserving the eerie forest. Each retelling proves the adaptability of famine-born imagery.

Ultimately, Hansel and Gretel endures because of its powerful images. Abandoned children, a house of sweets, and a threatening witch remain universally compelling. Art has preserved these symbols across centuries, ensuring they remain recognizable even outside their historical context. In this way, famine memory has become artistic legacy.

Key Takeaways

- Hansel and Gretel reflects famine memory through visual art as much as story.

- Illustrators like Richter, Doré, Rackham, and Nielsen shaped its imagery.

- Medieval manuscripts already depicted famine and abandonment artistically.

- The 1893 opera by Humperdinck fused music with elaborate stage design.

- Modern artists continue to reinterpret the tale in exhibitions and films.

FAQs

- Which famine may have inspired Hansel and Gretel?

The Great Famine of 1315–1317, depicted in manuscripts and chronicles. - Who illustrated early editions of the Grimms’ tales?

Their brother Ludwig Emil Grimm provided woodcuts in the early 1800s. - Which artists made the most famous Hansel and Gretel illustrations?

Ludwig Richter, Gustave Doré, Arthur Rackham, and Kay Nielsen. - What opera popularized the tale in performance art?

Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hansel und Gretel, premiered in Weimar in 1893. - How is the tale used in modern art?

Through picture books, films, museum exhibitions, and even sculpture.