Etruscan art stands as one of the most intriguing chapters in ancient Mediterranean history. Emerging in central Italy around 900 BC, the Etruscans developed a vibrant visual culture long before Rome’s dominance. This civilization flourished notably between 700 BC and 300 BC in regions that are now Tuscany, Lazio, and Umbria. Their art reflects a rich blend of indigenous innovation and external influence, helping modern scholars understand the broader artistic landscape of early Italy.

Two qualities define Etruscan art: expressive creativity and dynamic storytelling. While the Romans are often credited with shaping ancient Italian art, the Etruscans laid much of the groundwork through centuries of craftsmanship. From elaborate tomb frescoes to intricate metalwork, their artistic legacy reveals societal values and spiritual beliefs. In addition, archaeological discoveries since the 16th century, especially in burial chambers, have brought this once-forgotten culture back into broad scholarly view.

Why the Etruscans Matter in Art History

The Etruscans matter in art history because they connected the ancient world from the Greek East to the Italic West. Their artists adopted and adapted Greek motifs by the 7th century BC, long before similar adoption by the Romans. Studying Etruscan art offers insight into the transmission of artistic styles across cultures. Moreover, Etruscan influence on early Roman religious iconography and architectural ornamentation is unmistakable.

The Etruscan artistic imprint persisted even after Rome absorbed Etruria by the late 3rd century BC. While Latin literary sources such as Livy (born 59 BC) offer only fragmentary comments on Etruscan culture, material artistry preserves a vivid, enduring testament. Artifacts in museums around the world continue to educate and inspire. Through their art, the Etruscans emerge not as peripheral people but as central contributors to early Italian artistic identity.

Many scholars argue that without the Etruscans, Roman art and architecture would look markedly different. Their innovations in temple sculptures and bronze casting influenced early Roman aesthetics. The vitality and immediacy of Etruscan painting challenge the notion that Greek art was the sole standard in antiquity. In this way, the Etruscan worldview resonates across centuries, making their art history essential to any full understanding of classical antiquity.

The Origins and Influences of Etruscan Art

The roots of Etruscan art trace back to the Villanovan culture, which emerged in northern and central Italy around 900 BC. These early communities practiced cremation and produced simple geometric pottery, which evolved into more complex forms by the 8th century BC. As Etruscan urban centers like Veii and Tarquinia grew, so did interactions with Greek and Near Eastern civilizations. By 700 BC, Etruscan artists were incorporating external designs while adapting them to local tastes.

Trade networks across the Mediterranean brought not only goods but artistic knowledge to Etruria. Phoenician traders from the eastern Mediterranean arrived with luxury materials and motifs, enriching Etruscan visual vocabulary. The influence of Greek artisans became especially pronounced after 750 BC, as evidenced by pottery shapes and painted scenes that recall Corinthian prototypes. Egyptian stylistic elements also appeared through intermediary trade, creating a layered artistic synthesis.

Interaction with Greeks, Phoenicians, and Egyptians

Etruscan art reflects a tapestry woven with influences from Greece, Phoenicia, and Egypt. Greek vase painting, especially from Athens after 600 BC, offered narrative examples that Etruscan artists reinterpreted on their own ceramics. Phoenician metalwork techniques introduced new methods for working in bronze and precious metals. Egyptian iconography, while less direct, contributed symbolic motifs such as lotus patterns and winged figures.

Etruscan artisans never simply copied foreign art; they transformed it with distinctly local sensibilities. For instance, mythological scenes often depict characters in more animated and expressive poses than their Greek counterparts. Indigenous religious practices also shaped how motifs were used in tomb art and ritual objects. Consequently, Etruscan art remains unique despite its blend of external sources.

The result was a regional style that balanced foreign inspiration with native tradition. Centered around cities like Chiusi and Cerveteri, Etruscan workshops produced ceramics that spread across Italy. These objects served as tangible evidence of cultural exchange and adaptation. As a result, the art of this civilization offers scholars a window into Mediterranean interactions during the first millennium BC.

By the 6th century BC, Etruscan artistic influence extended into Rome itself. Roman architects and sculptors adopted Etruscan methods, particularly in temple design and bronze casting. This artistic flow from Etruria to Latium helped shape the visual culture of early Rome. Thus, understanding Etruscan art’s origins deepens our appreciation of later Italian artistic achievements.

Tomb Art and the Etruscan Afterlife

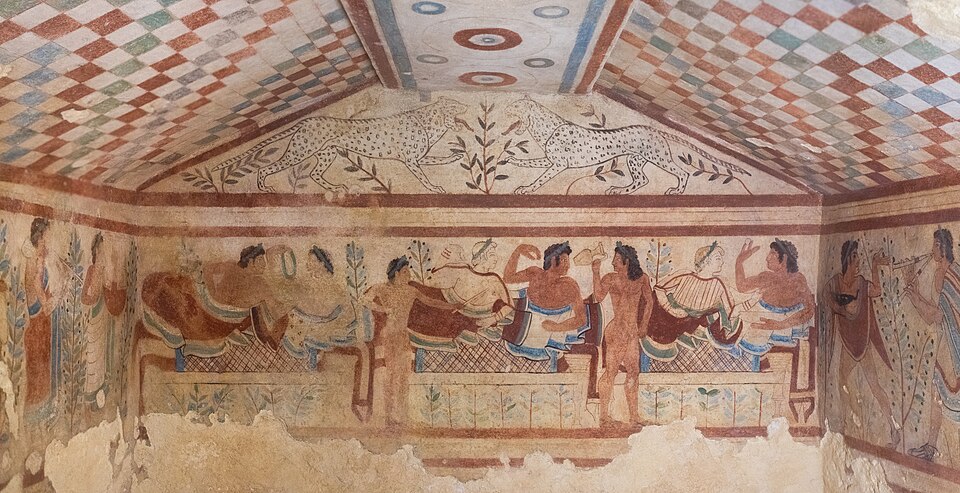

For the Etruscans, tomb art represented more than decoration; it served as a portal between life and death. Their necropolises, especially in Tarquinia, reveal vividly painted chambers that evoke the rhythms of everyday life and ritual. These tombs date predominantly from the 7th to 4th centuries BC and were constructed to mirror domestic interiors. This architectural design reflects a belief in continuity between earthly existence and the afterlife.

Inside, frescoes burst with color and movement, showing banquets, dancers, athletes, and musicians. The Tomb of the Leopards (circa 480 BC) remains one of the most iconic, depicting reclining figures celebrating life with stylized energy. Similarly, the Tomb of the Augurs (circa 520 BC) features attendants and ritual scenes that suggest civic and religious roles. Through these images, we see a society that embraced festivity and collective memory, even in the context of death.

Life-Like Frescoes from the Necropolises

Etruscan frescoes convey a vivid, almost tactile sense of life in antiquity. Artists used mineral pigments on plaster to create luminous scenes that survive in surprisingly vivid condition today. Figures move with expressive gestures, engaging in activities that suggest social harmony and spiritual reassurance. This approach contrasts with Greek funerary art, which often leans toward solemnity and restraint.

These frescoes also include symbolic imagery, such as drinking vessels and musical instruments, which held meaning in Etruscan ritual. The emphasis on festive banquets suggests that the afterlife was viewed as an extension of earthly pleasures rather than a somber departure. Such portrayals help modern viewers grasp the emotional and cultural priorities of this ancient people. The sensory richness of murals creates a powerful bridge across millennia, making the art feel alive again.

The artistic focus on daily life and ritual underscores the Etruscan belief in active life after death. Researchers believe these tombs served both as memorials for the deceased and as sacred spaces for familial remembrance. Artistic choices reflect not just aesthetics but deeply held spiritual practices. Through their frescoes, the Etruscans allow us to witness their values in bold hues and dynamic compositions.

By the late 4th century BC, as Roman influence grew, Etruscan tomb painting began to change in style and content. Yet even as external artistic currents arrived, local motifs and artistic priorities persisted. The enduring legacy of these murals continues to influence how scholars interpret ancient Italian art and spirituality. Thus, tomb art remains one of the most revealing sources of Etruscan life and belief.

Etruscan Sculpture: Terracotta and Bronze Masterpieces

Sculpture in Etruria embraced a wide range of materials, but none more so than terracotta and bronze. Terracotta, baked clay hardened in intense heat, was especially favored for architectural adornment. Large-scale statues, roof decorations, and figurative groups adorned temples and public spaces throughout the region. These works spoke to both religious devotion and civic pride.

Bronze casting likewise held a prestigious place in Etruscan art. Skilled foundries in cities like Vulci and Populonia produced vessels, figurines, and ritual implements that showcased metallurgical expertise. The lost-wax casting technique allowed artists to achieve fine detail and dynamic form. Many of these bronzes, discovered in tombs or sanctuaries, testify to a sophisticated artistic economy that flourished from the 7th through the 4th centuries BC.

The Apollo of Veii and Other Icons

Among the most renowned Etruscan sculptures is the Apollo of Veii, dating to around 510 BC. This striking painted terracotta figure once stood atop the Temple of Minerva at Portonaccio near modern-day Veii. With its animated stride and expressive features, Apollo contrasts sharply with the serene idealism typical of contemporary Greek sculpture. The figure’s vibrant energy conveys a sense of narrative motion frozen in time.

Other significant works include bronze mirrors engraved with mythological scenes and large-scale terracotta antefixes that capped temple roofs. These artifacts illuminate Etruscan religious life and aesthetic preferences. Sculptural decoration often emphasized dramatic form and emotional expression over strict naturalism. As a result, Etruscan sculpture contributes a distinct voice to the ancient Mediterranean artistic chorus.

The placement of sculpture in Etruscan temples also reflects broader cultural priorities. Figures like the Apollo once animated sacred spaces, serving both decorative and symbolic functions. This integration of art and architecture illustrates how Etruscans envisioned divine presence within daily life. Such artistic choices reveal a worldview in which the spiritual and the aesthetic were inseparable.

By the 3rd century BC, as Rome consolidated power in Italy, many Etruscan sculptural traditions were absorbed into Roman practice. Roman artisans adopted terracotta roofing elements and bronze casting techniques directly from their Etruscan predecessors. In this way, Etruscan innovation continued to shape Mediterranean art long after the civilization itself waned. Their sculptural legacy endures in collections across Europe and North America today.

Etruscan Metalwork and Daily Life Artifacts

Metalwork formed an essential expression of Etruscan artistic identity, ranging from jewelry to ritual vessels. Skilled smiths fashioned items in gold, silver, and bronze, often embellishing them with intricate engravings. These objects served not merely as adornments but as markers of status and spiritual connectivity. The craftsmanship reflects methods honed over generations and passed through artisan guilds.

Etruscan tombs have yielded remarkable examples of personal jewelry, including pendants, earrings, and fibulae (brooches) embellished with granulation and filigree. Wealthy families buried these treasures with the deceased as symbols of earthly achievement and spiritual protection. The presence of such items in burial contexts also allows modern researchers to gauge social hierarchies and gender roles in ancient Etruria. Such discoveries bring centuries-old stories into contemporary understanding.

Jewelry, Mirrors, and Ritual Vessels

Etruscan mirrors offer compelling insight into personal and ritual life from about 600 BC onward. These bronze mirrors often feature engraved scenes on their backs that depict mythological or ceremonial subjects. The craftsmanship demonstrates both technical precision and a narrative sensibility that rivals contemporary Greek work. Ritual vessels, such as situlae (bucket-shaped containers), likewise showcase elaborate decoration suited to sacred feasts.

The scenes chosen for mirrors and vessels reflect values tied to identity, spirituality, and social interaction. Funerary banquets, mythic encounters, and processions appear with vivid lines and balanced compositions. Women’s roles in Etruscan society, inferred in part from grave goods adorned with jewelry and mirrors, suggest a degree of social visibility unusual in many ancient cultures. These artifacts, therefore, not only delight the eye but also expand our understanding of gender and ritual in antiquity.

Metalwork objects also communicate the sensory richness of Etruscan life. At banquets, polished metal vessels would catch torchlight, gleaming as guests shared wine and music. The tactile feel of a finely wrought fibula against linen garments would speak to personal identity and social standing. By integrating daily use with artistic expression, Etruscan metalwork blurs the line between function and beauty.

The technical achievements evident in Etruscan metalwork influenced neighboring cultures, including early Rome. Roman luxury metalworking borrowed motifs and methods from Etruscan exemplars, especially in decorative brooches and ritual vessels. Thus, these artifacts represent not only aesthetic triumphs but also conduits of cultural transmission. Through them, the Etruscan artistic voice resonates across centuries.

Temples, Architecture, and Urban Art

Architecture occupied a central place in Etruscan artistic life, underpinning public, civic, and sacred spaces. Unlike Greek stone temples, Etruscan religious structures employed wood and terracotta as primary materials. These choices reflected both local resources and different conceptual approaches to sacred architecture. The result was a distinctly Italic architectural language that prioritized monumentality and dynamic form.

Etruscan temples typically featured deep porches and multiple cellae (inner chambers), accommodating several gods or cults within one structure. Rooflines were animated by terracotta sculptures, including figures of deities and mythic creatures. Urban planning likewise reveals advanced civic organization, from paved roads to systematically arranged settlements. Collectively, these elements portray a society in which artistic design and practical construction fused seamlessly.

Etruscan Temples vs. Greek Temples

Comparing Etruscan and Greek temples underscores key differences in cultural priorities and aesthetic outcomes. Greek temples, built primarily of marble and limestone, emphasized proportional harmony and elevation on high platforms. In contrast, Etruscan temples sat lower to the ground, with broad staircases and expansive roofspaces designed for sculptural display. This orientation created a more immediate, earthbound relationship between worshippers and the sacred.

Terracotta elements in Etruscan architecture were not merely decorative; they were structural components as well, protecting wooden beams and adding color to façades. Figures such as the Apollo of Veii adorned roof ridges to convey divine presence over communal life. Urban art also appears in public spaces through carved stone columns and tomb markers. These features demonstrate how aesthetics enlivened both spiritual and civic domains.

Moreover, Etruscan urban centers such as Marzabotto (flourishing by the 6th century BC) reveal regular street grids and sophisticated drainage systems. These infrastructures anticipated many practices later adopted by Roman planners. The integration of art into these functional spaces elevated ordinary experience, blending utility with beauty. Through architectural innovation, the Etruscans shaped environments that reflected societal values at every level.

By the 3rd century BC, as Roman political control expanded, many Etruscan architectural traditions were absorbed and transformed. Roman builders drew on Etruscan temple layouts and architectural ornamentation as they developed their own monumental constructions. Through such adoption, Etruscan design continued to influence the course of Italian architectural history. Their urban and sacred art thus stands as a testament to their enduring legacy.

Legacy and Rediscovery of Etruscan Art

The legacy of Etruscan art survived beyond the civilization’s political decline in the 3rd century BC. As Rome consolidated power, Etruscan artistic forms found new life in Roman sculpture, metalwork, and religious architecture. During the Renaissance, Italian scholars and artists began unearthing Etruscan tombs once more, sparking renewed interest. Excavations in the 16th and 17th centuries brought artifacts to light that challenged prevailing narratives about Italy’s artistic past.

Archaeological exploration accelerated in the 18th and 19th centuries with systematic digs in sites such as Cerveteri and Tarquinia. These efforts revealed rich necropolises filled with frescoes, ceramics, and jewelry, reshaping scholarly understanding. Museums across Europe, including the Villa Giulia in Rome and major national collections, amassed Etruscan art for public study and appreciation. These rediscoveries reinstated the Etruscans as pivotal contributors to ancient Mediterranean culture.

From Forgotten Graves to Museum Treasures

Etruscan art now resides in institutions worldwide, showcasing works that date from the 9th century BC through the 1st century BC. Exhibits feature tomb fresco fragments, bronze statuettes, and finely crafted pottery that illustrate centuries of artistic evolution. These museum treasures offer tangible touchpoints for learning about a people whose written history remains scarce. Through curated displays, scholars and visitors alike encounter the complexity of Etruscan artistic achievement.

Modern archaeological science continues to refine our understanding of Etruscan art and society. Techniques such as pigment analysis and 3D scanning reveal details once invisible to earlier generations of researchers. Fieldwork in Italy’s ancient cemeteries still yields new discoveries, deepening historical narratives. Educational programs and exhibitions help bridge past and present, ensuring that this artistic heritage remains relevant.

Contemporary scholars emphasize the Etruscan role in shaping Roman artistic identity, particularly in sculpture and urban planning. This reassessment challenges earlier dismissals of the Etruscans as mere precursors to Rome. Recognizing their contributions enriches the broader story of Mediterranean civilization. Consequently, Etruscan art occupies a secure place within both academic study and public imagination.

Despite centuries of neglect and rediscovery, Etruscan art endures as a testament to human creativity and cultural exchange. These works remind us that artistic innovation knows no single origin but flourishes through interaction and adaptation. From tomb walls to terracotta temples, the Etruscan artistic legacy continues to inspire and educate. Their visual language remains as captivating today as it was millennia ago.

Key Takeaways

- Etruscan art flourished in central Italy from about 900 BC to the 3rd century BC and influenced early Roman culture.

- Tomb frescoes at sites like Tarquinia showcase vivid depictions of banquets and ritual practices.

- Terracotta and bronze sculptures, including the Apollo of Veii (circa 510 BC), reveal dynamic artistic expression.

- Metalwork and daily artifacts like mirrors and jewelry reflect both social identity and ritual use.

- Rediscovery in the Renaissance and systematic excavation in later centuries restored Etruscan art to global recognition.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What period did Etruscan art span?

Etruscan art developed between about 900 BC and the 3rd century BC. - Where was the center of Etruscan artistic activity?

The heart of Etruscan art lay in central Italy, especially Tuscany, Lazio, and Umbria. - What materials did Etruscan sculptors use most?

Terracotta and bronze were primary materials in Etruscan sculpture. - How were Etruscan tombs decorated?

Tombs were often painted with frescoes depicting lively banquets and rituals. - Why is Etruscan art important today?

Etruscan art illuminates ancient Italian culture and influenced later Roman aesthetics.