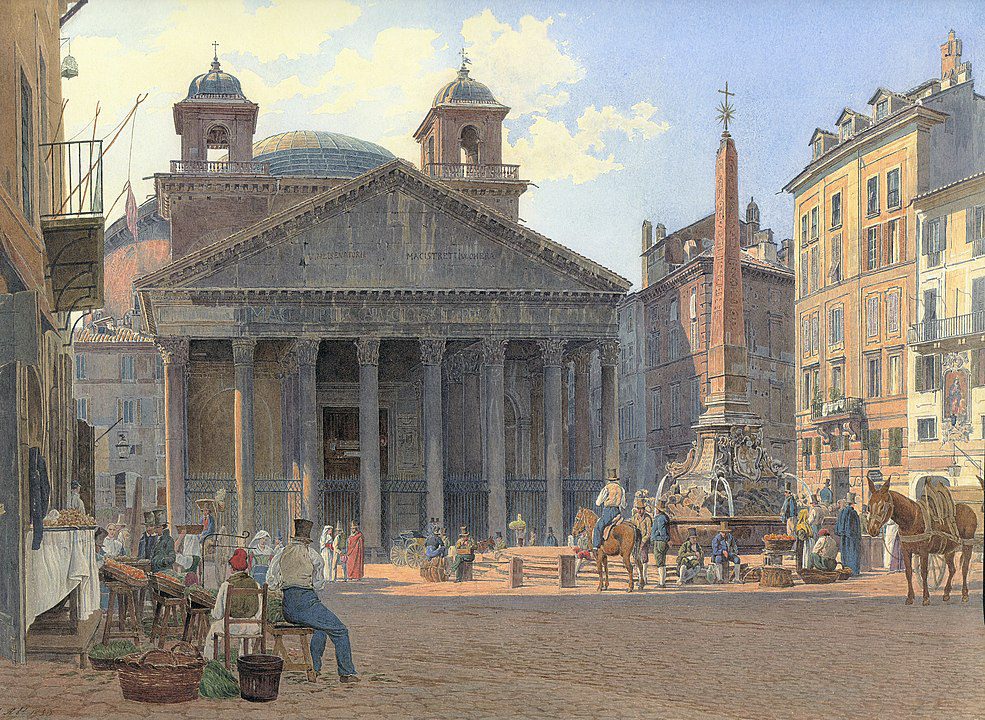

In the heart of ancient Rome stands a building that has defied the passage of time more than any other from the classical world—the Pantheon. Completed around 126 AD during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, this remarkable structure has functioned as a temple, a church, and a symbol of Roman architectural brilliance. It holds the distinction of having the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world, a title it still carries nearly 2,000 years later.

The Pantheon’s name derives from the Greek “pan” (all) and “theos” (gods), originally intended as a temple to all Roman deities. But the building we see today is not the original. Two earlier temples built on the site—one under Marcus Agrippa in 27–25 BC and another after it burned down—were destroyed. What stands now is Hadrian’s reconstruction, though he retained Agrippa’s name on the inscription above the portico.

From its massive granite columns to its perfectly proportioned rotunda, the Pantheon reflects Roman mastery of engineering, geometry, and materials. It is not just a relic of antiquity—it has been a working building since its construction, adapted for Christian worship in the 7th century and used continuously ever since. Today, it serves as a Roman Catholic church and a powerful reminder of the Roman Empire’s architectural legacy.

No other building from the ancient world has had such enduring influence on Western architecture. From Renaissance cathedrals to government buildings and modern museums, the Pantheon’s imprint is everywhere. Its combination of structural daring and spiritual symbolism makes it one of the greatest feats of architecture ever built.

From Agrippa to Hadrian: Rebuilding the Pantheon

The Pantheon’s history begins with Marcus Agrippa, a close friend and son-in-law of Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. Around 27 BC, Agrippa commissioned a temple on this site in the Campus Martius, a large open field used for public gatherings and military exercises. The original structure was rectangular, in line with traditional Roman temple design, but it was destroyed by fire around 80 AD.

The temple was rebuilt under Domitian, only to be destroyed again in 110 AD, likely due to lightning. Around 118–125 AD, Emperor Hadrian began a complete overhaul of the site. Rather than follow the traditional rectangular plan, Hadrian introduced a bold new design—a circular rotunda capped by a massive dome, fronted by a traditional portico. The result was an architectural hybrid that bridged tradition and innovation.

Hadrian, who was deeply interested in architecture and often took a personal role in building design, chose not to inscribe his own name on the temple. Instead, he honored Agrippa by preserving the original dedication on the façade: “M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT”, which translates to “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time, built this.”

Despite that humble nod to tradition, Hadrian’s Pantheon was revolutionary. It redefined what a Roman temple could be—transforming it from a house of one deity into a cosmic space that celebrated the heavens and imperial authority alike. Though its exact original function is still debated by scholars, most agree that it served both religious and symbolic roles, emphasizing Rome’s dominance over both earth and sky.

The fact that Hadrian’s reconstruction has survived for nearly two millennia, largely intact, speaks not only to Roman construction techniques but also to the Pantheon’s timeless design and adaptability. While fires, invasions, and decay claimed countless Roman buildings, the Pantheon endured.

The Portico: Classical Tradition at the Entrance

Approaching the Pantheon, the first architectural feature that greets the eye is the portico, an imposing rectangular structure with a colonnade of 16 massive Corinthian columns. Each column stands over 11 meters tall and is made of Egyptian granite with Greek marble capitals. Transporting these monolithic columns from quarries in Egypt to Rome was a feat of logistics and imperial wealth, underscoring Rome’s command over distant lands.

The portico measures approximately 33 meters wide and 15 meters deep, creating a grand stage-like setting for worshippers and visitors. The triangular pediment once held sculptural decoration, now lost, but its form continues to symbolize classical ideals of balance and order. The traditional temple front suggests continuity with Roman and Greek religious practices—even though the space behind it broke dramatically with architectural convention.

Behind the front row of columns is a rectangular pronaos, or porch, leading into the rotunda. Here, bronze doors more than seven meters tall open into the vast circular interior. Though not the originals, the current doors date to antiquity and reinforce the grand transition from outer world to sacred space.

Despite being a front-facing structure, the portico is slightly awkward in proportion to the rotunda behind it—architectural evidence suggests it may have been intended to be taller, or even planned differently. These inconsistencies hint at design changes during construction, yet they don’t detract from the Pantheon’s overall harmony. Instead, they illustrate the challenges of integrating classical elements with radical spatial innovation.

The portico remains a defining image of Roman architecture. Its columns and pediment have inspired countless civic buildings, courthouses, and memorials across the West. It’s the bridge between the familiar and the sublime, drawing visitors into an experience that still awes them today as it did nearly 2,000 years ago.

The Dome and Rotunda: Engineering a Heavenly Space

Stepping into the Pantheon’s rotunda is like entering a sacred cosmos. The building’s circular interior, measuring 43.3 meters in diameter—exactly equal to its height—creates a perfect sphere inside a cylinder. This symmetry is not just mathematical—it’s spiritual. The architects used geometry to reflect the divine order of the universe, with the dome representing the heavens and the circular floor symbolizing the earthly realm.

The crowning glory of the structure is its dome, still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. To achieve this feat, Roman engineers used a brilliant system of material gradation. Heavier materials like travertine were used at the base, while lighter materials such as tufa and pumice were used toward the top. The thickness of the dome also tapers from 6.4 meters at the base to just 1.2 meters at the crown.

At the center of the dome is the oculus, a circular opening 8.2 meters wide that allows natural light to pour into the interior. The oculus is the building’s only source of direct light and plays a symbolic role: it represents the sun, the eye of the gods, or even a passage to the divine. Sunlight moves across the walls and floor throughout the day, creating an ever-changing play of light that transforms the space without the need for artificial lighting.

To reduce weight and provide aesthetic rhythm, the interior of the dome features five concentric rings of coffers—sunken panels that both lighten the load and enhance visual complexity. Originally, these coffers may have been decorated with gilded rosettes, further emphasizing the celestial theme.

The engineering of the Pantheon’s dome wasn’t just advanced—it was revolutionary. Roman concrete, known as opus caementicium, allowed the builders to create a massive span without internal supports. That innovation has influenced domed structures ever since, from Brunelleschi’s Dome in Florence to St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican and even the U.S. Capitol.

Interior Design: Harmony, Symbolism, and Materials

The Pantheon’s interior was designed not only to impress but to convey a deep sense of cosmic harmony and imperial authority. The space is divided into three main zones: the floor, the circular wall with its niches and columns, and the soaring dome above. These layers mirror the classical tripartite division of the cosmos—earth, man, and heaven—each represented in geometry, proportion, and light.

The floor of the rotunda is made from a geometric arrangement of colored marbles, including porphyry from Egypt, yellow giallo antico from Tunisia, and green serpentine from Greece. These materials weren’t just chosen for their beauty—they showcased Rome’s dominion over the known world, as every stone came from a far-flung province of the empire. The floor design follows a series of circular and square patterns, reinforcing the harmony of the dome above.

The circular drum features seven large niches, alternating between rectangular and semicircular shapes, originally intended to house statues of the gods or deified emperors. Corinthian columns made of Egyptian granite support the entablature above each niche. Between the main niches are smaller recesses and blind windows, contributing to the rhythm and balance of the wall. This interplay of light, shadow, and symmetry gives the interior a fluid and expansive feel.

Above, the dome transitions seamlessly from the drum with a simple cornice, guiding the eye upward. As daylight enters through the oculus, it animates the building throughout the day. Sunlight moves across the coffered dome and lands on different niches and surfaces, highlighting details and casting dramatic shadows. The space seems alive—changing with time, just like the world it represents.

Originally, the interior was richly decorated with bronze, gold, and painted detail. The exact nature of some decorations has been lost, especially after Pope Urban VIII Barberini ordered the removal of much of the bronze ceiling in the 17th century to be repurposed for Bernini’s Baldacchino in St. Peter’s. Still, enough remains to convey the splendor and symbolism that defined the original design.

The Pantheon’s Function Over Time

The original function of the Pantheon remains a subject of scholarly debate. While the name suggests a temple to “all gods,” there’s little evidence of polytheistic cult activity inside. Some believe it served as a dynastic monument or a space for imperial ceremonies that linked the emperor to the divine. Whatever the case, the structure’s design clearly intended to evoke cosmic power, imperial majesty, and spiritual transcendence.

A defining moment in the Pantheon’s history came in 609 AD, when the Byzantine emperor Phocas gifted the building to Pope Boniface IV, who consecrated it as the Church of St. Mary and the Martyrs. This act marked the Pantheon’s transformation from a pagan temple to a Christian church, ensuring its preservation while countless other ancient Roman temples were abandoned or dismantled.

As a church, the Pantheon was used for Mass and religious processions, but it also became a burial place for notable Italians. Raphael, the High Renaissance painter, was interred here in 1520. Later, Italian kings Victor Emmanuel II and Umberto I, along with Queen Margherita, were also laid to rest in side chapels within the rotunda.

Throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods, the Pantheon continued to attract admiration from artists and architects. Brunelleschi, Michelangelo, and Palladio all studied its form, proportions, and dome. It served as both inspiration and benchmark, a perfect classical model that later Western architecture constantly referred back to.

Its continued use has made the Pantheon unique. Unlike most ancient Roman temples, which became ruins or museums, it has remained a living building. Whether as a site of worship, burial, or inspiration, it has never fallen out of public use—a fact that speaks to the timeless power of its design.

Restoration, Conservation, and Modern Use

The Pantheon’s endurance over two millennia is not merely due to its original construction—its survival has also depended on continuous use and conservation. As a church, it was regularly maintained by the Catholic Church, and during the Renaissance and Baroque eras, it saw restorations that preserved its structure but also altered its artistic features.

One of the most significant changes came in 1632, when Pope Urban VIII commissioned the removal of the portico’s bronze ceiling beams. These were melted down and repurposed for Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s baldachin at St. Peter’s Basilica. This act caused controversy even at the time, and the phrase “Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini” (“What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did”) was coined in protest.

Over the centuries, minor earthquakes and flooding threatened the Pantheon, but its sound construction and thick masonry helped it weather these threats. In the 19th century, the Italian state took over management of the site, and it became a national monument after Italian unification. Restoration projects focused on preserving the dome, repairing the floor, and cleaning the ancient marble.

In modern times, conservation efforts have included cleaning soot from the dome’s coffers, stabilizing the portico’s columns, and improving visitor infrastructure. The oculus, once left open to the elements, now features subtle drainage systems on the floor to deal with rainwater that enters the building.

Despite being one of the most visited sites in Italy—with over 7 million visitors annually—the Pantheon continues to function as a working church, with regular Masses and special ceremonies held throughout the year. In 2023, Italy introduced a small entrance fee for tourists, though access for religious worship remains free.

Its conservation is now a collaboration between the Italian Ministry of Culture, the Diocese of Rome, and international partners, ensuring that the Pantheon will be preserved not just as an artifact of the past, but as a sacred space that still speaks to modern generations.

Conclusion: The Pantheon as a Legacy of Empire and Art

The Pantheon stands as one of the few surviving monuments from the ancient world that still serves its original purpose: to inspire awe. While its religious function has shifted—from a Roman temple to a Christian church—its architectural spirit remains unchanged. It invites everyone who enters to look upward, to contemplate the heavens, and to experience the mystery of space, light, and time.

What makes the Pantheon so exceptional is its unity of form and meaning. Its geometry is not just elegant—it’s cosmic. Its materials are not just durable—they’re symbolic. Its dome is not just a roof—it’s a vision of the universe in stone and concrete. Every detail, from the portico columns to the patterned marble floor, reinforces a worldview where empire, divinity, and architecture converge.

The building’s influence can be felt across centuries and continents. It shaped Renaissance ideals of beauty, it guided Enlightenment architects in Europe and America, and it continues to be a model for sacred and civic architecture alike. The Pantheon is not merely admired—it is emulated, quoted, and honored in buildings from Paris to Washington, D.C.

But above all, the Pantheon endures because it was built to last—not only structurally, but spiritually. It speaks across millennia to what humans value most: order, meaning, and the presence of something greater than ourselves. In its shadow, one feels not only the greatness of Rome but the timeless desire to build something eternal.

Key Takeaways

- The Pantheon was rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian around 126 AD on the site of earlier temples.

- Its dome remains the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.

- The building’s perfect symmetry and oculus reflect Roman cosmic and imperial symbolism.

- Originally a pagan temple, it became a Christian church in 609 AD and remains in use today.

- The Pantheon’s influence can be seen in architecture from the Renaissance to modern public buildings.

FAQs

- Who built the current Pantheon?

Emperor Hadrian built it around 118–126 AD, although it retains Agrippa’s original dedication. - What is the Pantheon’s dome made of?

Roman concrete, with lighter materials like pumice near the top to reduce weight. - Is the Pantheon still a church today?

Yes, it is known as the Church of St. Mary and the Martyrs and holds regular services. - Why does the Pantheon have a hole in the roof?

The oculus lets in natural light and symbolizes the heavens; it also acts as ventilation. - Can you visit the Pantheon?

Yes, it is open to the public daily, with an entry fee for tourists and free access for worship.