Vlaho Bukovac was born on July 4, 1855, in the small seaside town of Cavtat, part of Dalmatia under the Austrian Empire at the time. His birth name was Biagio Faggioni, reflecting his Italian heritage on his father’s side. The young Bukovac grew up amid a mix of cultures—Croatian, Italian, and Austro-Hungarian—which would later influence the rich diversity in his artwork. Despite the charming surroundings of the Adriatic coast, his early life was marked by hardship and a longing for opportunity.

As a teenager, Bukovac embarked on a journey to the United States around 1873, where he worked on ships and eventually spent time in Peru. While there, he began sketching portraits and experimenting with painting—initially as a hobby to pass time but eventually as a growing passion. His natural skill began to show even without formal training, and soon he realized that art might be his life’s calling. After several years abroad, he returned to Europe determined to pursue serious artistic education.

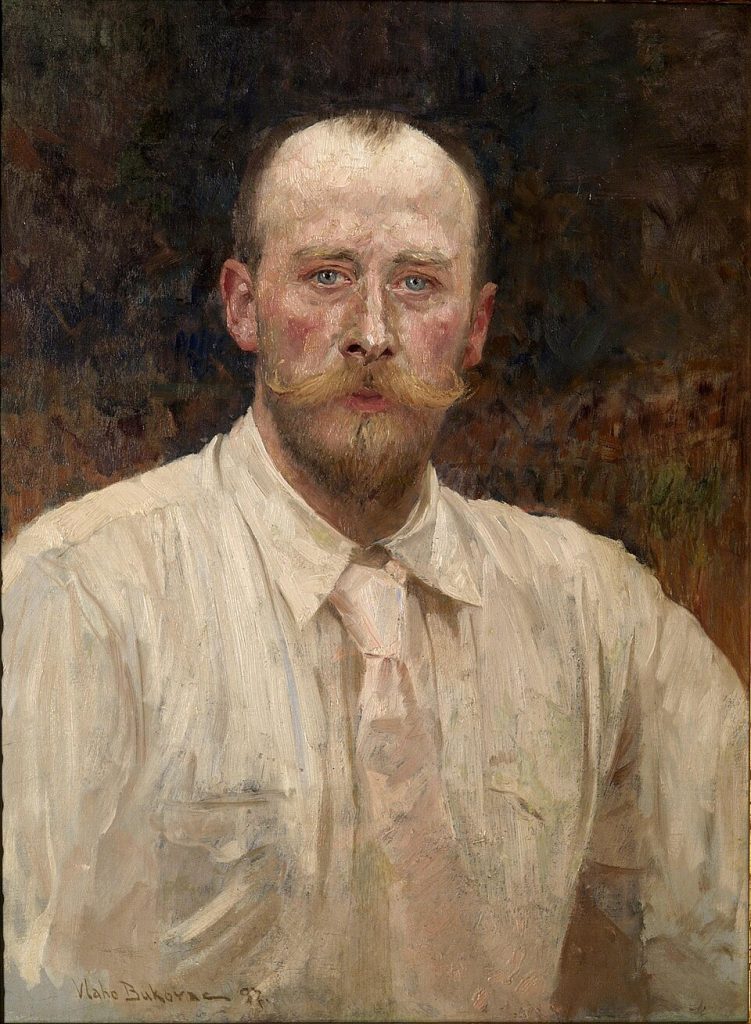

In 1877, Bukovac enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a major turning point in his life and career. He studied under Alexandre Cabanel, a renowned French academic painter who championed traditional techniques and refined realism. Cabanel’s emphasis on detail and composition left a deep impression on Bukovac, who quickly rose to prominence among his peers. While in Paris, Bukovac also adopted his Slavic name officially—Vlaho Bukovac—reaffirming his connection to his Croatian identity.

Before arriving in Paris, Bukovac had briefly studied with Domenico Morelli in Italy, which helped refine his technique and broaden his classical foundation. This early exposure to both the Southern Italian and French academic styles would give Bukovac a unique edge in his future works. By the time he completed his studies in the early 1880s, he was already receiving minor commissions and had built a reputation for artistic excellence. These formative years laid the groundwork for the remarkable and far-reaching career that would follow.

Rise to Prominence in Paris and Zagreb

Bukovac’s big break came in 1878 when he debuted at the prestigious Paris Salon, the most important art exhibition in France at the time. His painting, “Une fleur (A Flower),” drew immediate attention for its delicate rendering and emotional intensity. This piece not only launched his reputation in France but also earned praise from critics and patrons throughout Europe. With this success, he cemented his place among the rising stars of the European art world.

Throughout the 1880s, Bukovac continued to gain acclaim for his romantic and academic compositions, many of which featured idealized female figures, mythological subjects, and serene landscapes. He was known for his technical precision and graceful compositions, often comparable to his mentor Cabanel. However, unlike many French academic painters, Bukovac never abandoned his Slavic identity. Even while living in Paris, he maintained contact with Croatian intellectuals and nationalists who encouraged him to return and contribute to the cultural life of his homeland.

By the early 1890s, Bukovac had accepted their call and moved to Zagreb, where he quickly became a central figure in Croatia’s artistic renaissance. His presence invigorated the local art scene, and his works were now seen not just as technically skilled, but as vital expressions of national pride. In Zagreb, he painted numerous portraits of political, cultural, and religious leaders, each infused with a deep sense of purpose and patriotic fervor. Through these works, he helped elevate the status of Croatian art and culture at a time when national identity was under pressure from imperial influence.

Bukovac’s career during this period blended prestige with mission. While still maintaining connections to Paris and continuing to exhibit internationally, he poured himself into the development of Croatian art institutions. He gave lectures, mentored young artists, and helped organize exhibitions that showcased domestic talent. His dual role as both artist and cultural ambassador positioned him as a bridge between Western European refinement and Eastern European tradition.

International Success and Major Exhibitions

As Bukovac’s reputation grew, so did the scope of his exhibitions, attracting audiences well beyond Croatian or even French borders. One of his most significant appearances was at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, where his works were displayed alongside those of Europe’s leading masters. His participation signaled that he was no longer just a regional talent, but a truly international figure. These exhibitions opened doors for commissions from the upper echelons of society across Europe.

Among his most notable patrons were Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria and King Nicholas I of Montenegro, both of whom admired Bukovac’s ability to capture nobility with depth and dignity. His royal portraits from this era blend academic finesse with subtle personal touches, setting them apart from the more rigid court paintings of the time. Through these commissions, Bukovac gained not only financial support but also a stronger foothold in influential circles. His network now spanned courts, academies, and artistic salons across the continent.

During this phase of his career, Bukovac’s style began to evolve. Though rooted in academic realism, his brushwork became more fluid, and his use of color more daring. Exposure to French Impressionists and plein air painters pushed him to explore new techniques. He started embracing natural light, open compositions, and a more expressive palette, particularly in his landscapes and genre scenes.

This artistic maturation coincided with his ongoing dedication to promoting national themes in his art. Even while painting in foreign courts or exhibiting in cosmopolitan settings, Bukovac often incorporated Slavic motifs and regional elements. His unique fusion of international technique and patriotic spirit gave his work both universal appeal and cultural weight. It was a balancing act few artists managed so well.

Return to Homeland and the “Croatian School” Movement

By the late 1890s, Bukovac had firmly re-established himself in Croatia and set out to build something lasting. In 1897, he co-founded the Croatian Society of Artists, a major institutional step in shaping the local art scene. This society not only provided a platform for Croatian painters and sculptors but also emphasized national pride and self-determination through art. Bukovac’s leadership was instrumental in legitimizing this movement both at home and abroad.

He soon began promoting what came to be known as the “Zagreb Colorist School,” a movement marked by vivid hues and expressive brushwork. His own palette became noticeably more radiant, using color not just to depict reality but to evoke emotion and atmosphere. Under his influence, Croatian painting took on a new life, breaking away from strict realism and embracing modern European trends. Yet Bukovac always emphasized that color should serve the subject—not overpower it.

In 1903, Bukovac was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, one of the most prestigious positions in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His move to Prague allowed him to further influence a new generation of artists, including Jozo Kljaković, Mirko Rački, and other future leaders of Croatian modernism. He remained in this post until 1920, advocating for a blend of technical skill and national character in all artistic expression. This philosophy became the foundation of his educational legacy.

During this period, Bukovac also produced monumental public works that celebrated Croatian heritage, including murals, altarpieces, and civic portraits. These projects fused national themes with personal passion, resulting in pieces that were both artistically impressive and culturally meaningful. Through his efforts, the Croatian art world grew in confidence and began asserting itself on the European stage. Bukovac’s vision had finally borne fruit.

Artistic Style and Thematic Explorations

Bukovac’s painting style defied easy categorization, blending academic training with vibrant experimentation. He began with highly detailed realism, often emphasizing idealized human forms and mythological content. But over time, his works became more expressive, with freer brushstrokes and luminous color schemes. This transformation reflected both personal growth and a broader shift in European art during the turn of the century.

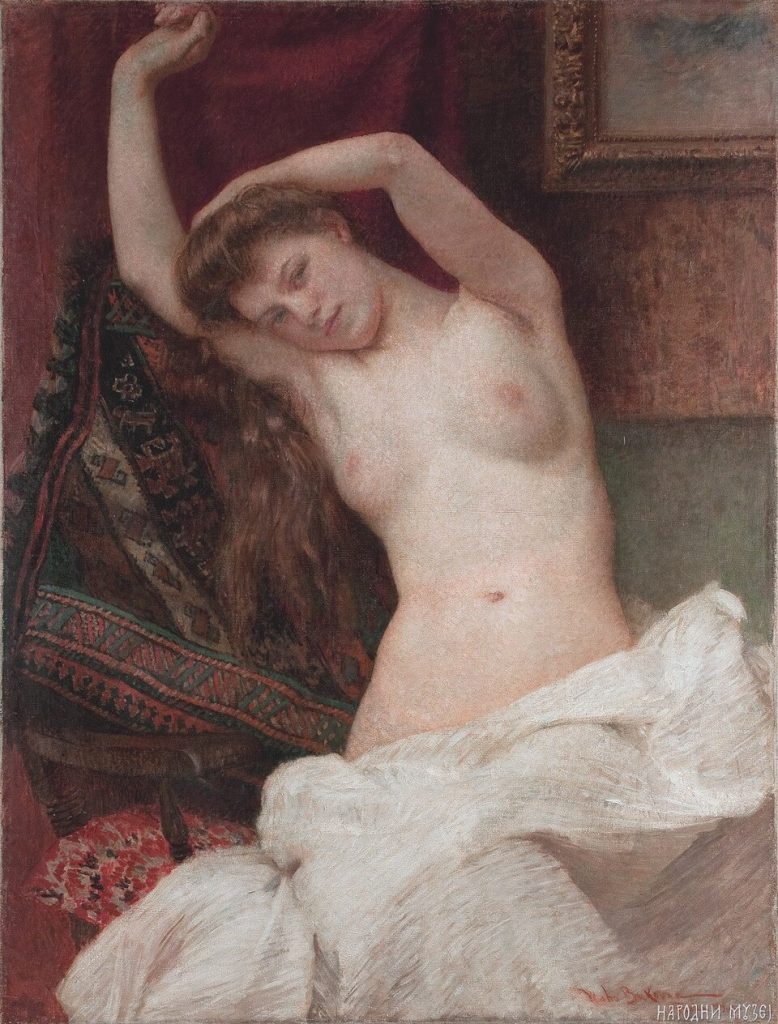

His themes were rich and varied. Religious allegories, poetic dreamscapes, historical episodes, and portraiture all found a place in his oeuvre. Perhaps most famous is his 1884 painting “The White Slave,” a haunting depiction of beauty and vulnerability that captivated critics and audiences alike. Other celebrated works include “Gundulić’s Dream,” a powerful blend of nationalism and mysticism, and the “Miroslav Gospel” series, which depicted the cultural spirit of the Croatian people. Each painting was more than a visual feast—it was a message wrapped in paint.

Color and texture became increasingly central to his approach. Bukovac understood that technique alone couldn’t convey the fullness of human experience. By using layered pigments and light-saturated tones, he drew viewers into his scenes as if they were living them. His brushstrokes—at times precise, at others swirling—created rhythm and mood, turning his canvases into narratives of faith, struggle, and hope.

While some critics called him overly sentimental, Bukovac never abandoned his belief in art’s moral and cultural mission. He saw painting as both a craft and a calling, a way to elevate the soul while honoring heritage. His style, shaped by the academic world but liberated by passion, struck a balance between discipline and inspiration. That blend made him a beacon in an age of artistic upheaval.

Personal Life, Family, and Final Years

Behind the success and acclaim, Bukovac’s personal life remained deeply rooted in family and tradition. He married Jelica Pitarević in 1886, a union that brought stability and companionship to his often-traveled existence. Together, they had several children, including their daughter Ivanka Bukovac, who followed in her father’s footsteps to become a painter. The Bukovac household was known for its warmth, intellect, and artistic spirit.

In the early 1900s, Bukovac divided his time between Prague and his native Cavtat, where he maintained a family home and studio. Despite his academic commitments and international obligations, he always returned to the Adriatic coast for inspiration and peace. These later years were filled with both reflection and production, as he worked on portraits, landscapes, and religious works. His Cavtat studio became a local landmark, eventually preserved as the Bukovac House Museum.

Though slowing with age, Bukovac remained active well into his sixties. In 1920, he retired from teaching at the Prague Academy but continued to paint until his final illness. His last works, created in Cavtat’s golden light, were quiet, contemplative, and deeply personal. On April 23, 1922, he passed away in Prague, leaving behind a towering legacy in both Croatian and European art.

He was buried in his hometown of Cavtat, where a grateful nation continues to honor his memory. Annual commemorations, museum exhibitions, and scholarly studies ensure that his contributions are not forgotten. His descendants, especially Ivanka, helped preserve his works and letters for future generations. In both his public achievements and private virtues, Bukovac remained a model of dedication and grace.

Legacy and Influence on Balkan Art

The legacy of Vlaho Bukovac reaches far beyond the borders of Croatia. He is widely recognized as the founder of modern Croatian painting and a key cultural figure in the Balkans. His ability to harmonize European technique with national themes influenced artists across Central and Eastern Europe. Even a century after his death, his style and spirit remain influential.

Bukovac’s home in Cavtat was converted into the Bukovac House Museum, where visitors can view his original works, sketchbooks, and personal artifacts. The space is a time capsule of 19th-century artistic life, filled with the textures and colors that defined his world. Each room tells a story—of talent, struggle, and patriotic devotion. For many Croatians, it is a site of pilgrimage and inspiration.

His works have been featured in major retrospectives in Zagreb, Belgrade, Prague, and Vienna, showcasing his importance not only regionally but across Europe. Scholars have increasingly reevaluated Bukovac’s role, placing him within broader narratives of European Romanticism, Symbolism, and Impressionism. He is now seen not just as a Croatian painter but as a significant European master. This renewed appreciation confirms his status as a timeless figure.

Bukovac’s greatest contribution may have been his ability to unite artistic excellence with cultural identity. In an age when national values were often under threat, he used his canvas to defend and define them. His life and work offer a model of how art can serve both beauty and truth, both individual vision and collective heritage. In today’s fragmented cultural landscape, his legacy stands as a beacon of tradition, craftsmanship, and principled purpose.

Key Takeaways

- Vlaho Bukovac was born in Cavtat in 1855 and studied in Paris under Alexandre Cabanel.

- He gained fame at the Paris Salon and exhibited throughout Europe, including royal commissions.

- He played a major role in founding Croatia’s national art institutions and taught in Prague.

- His style evolved from academic realism to impressionistic colorism with strong national themes.

- His legacy endures through museums, retrospectives, and the lasting impact on Balkan art.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Where was Vlaho Bukovac born?

He was born in Cavtat, Dalmatia (then part of the Austrian Empire) on July 4, 1855. - What is Bukovac known for?

He is known for blending academic painting with national themes and mentoring a new generation of Croatian artists. - Where did Bukovac study art?

He studied at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris under Alexandre Cabanel. - Did he have any children who were artists?

Yes, his daughter Ivanka Bukovac was also a painter and preserved much of his legacy. - When and where did Bukovac die?

He died on April 23, 1922, in Prague and is buried in his hometown of Cavtat.