Pierre Auguste Cot was born on February 17, 1837, in the small town of Bédarieux, nestled in the Hérault region of southern France. Raised in a modest middle-class household, Cot was the son of a successful tradesman whose steady income allowed the family to offer Pierre a good education. His early years in the Languedoc countryside surrounded him with rustic charm, seasonal rhythms, and a classical French culture that would later permeate his art. Though far from the grandeur of Paris, this rural environment instilled in Cot a deep appreciation for the natural beauty and storytelling found in everyday life.

The region of Hérault during the 1830s and 1840s remained largely agrarian, with strong ties to traditional Catholic values and conservative rural customs. These surroundings shaped Cot’s view of family, beauty, and structure—values that would surface time and again in his paintings. His early drawings, often created with simple charcoal and paper, showed a tendency toward idyllic scenes of youth and nature. These impressions of country life later informed his romantic paintings, rich with harmony and innocence.

The Rural Roots of a Romantic Vision

Cot’s provincial upbringing gave him more than just quiet surroundings; it gave him a lens through which he viewed life as a tapestry of harmony, emotion, and idealized love. As a child, he often observed the changing seasons, the rituals of daily work, and the small-town celebrations that emphasized community and storytelling. This atmosphere imbued him with a poetic sense of detail, which would eventually blossom in his allegorical canvases. His understanding of romance wasn’t born in the salons of Paris, but in the whispers of the wind through vineyard leaves and the joyful bustle of village life.

Though Cot would eventually move into the elite artistic circles of the French capital, he carried with him the humility and work ethic forged in his early years. Unlike many of his more avant-garde peers, Cot held fast to traditional artistic values and the classical style. His upbringing in Bédarieux was not just a backdrop but a cornerstone of his identity. In many ways, the artist never fully left the countryside—he simply transported its spirit onto his canvas.

Education and Academic Formation

Pierre Auguste Cot’s formal artistic journey began when he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse, a school known for its disciplined training in the classical arts. He was a devoted student, and his early talent quickly earned him the support of mentors who saw in him the promise of an exceptional draftsman. Driven by a thirst for greater refinement, Cot later moved to Paris, where he was admitted into the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. This marked the start of a rigorous and foundational period of study that would shape the rest of his career.

In Paris, Cot trained under several prominent artists, most notably Léon Cogniet, Alexandre Cabanel, and William-Adolphe Bouguereau—three giants of academic painting. These men were masters of proportion, mythological themes, and technical execution, all of which Cot absorbed with diligence. Through this instruction, Cot developed his hallmark style: smooth, idealized forms, elegant compositions, and a reverence for beauty. He became known for his ability to blend the technical perfection of his teachers with his own emotional vision.

Learning Under Masters of the French Academy

Cabanel, in particular, influenced Cot’s preference for romantic themes paired with classical poses and expressive detail. Under Bouguereau’s guidance, Cot honed his skill in rendering the human form with such delicacy that even the softest fabrics or barest expressions conveyed depth. While other young painters of the time were turning to Impressionism, Cot doubled down on traditional academic methods, believing they best conveyed timeless truths. His resistance to modernist trends wasn’t stubbornness—it was a commitment to enduring values in art.

By the time he graduated in the early 1860s, Cot had mastered not only anatomy and color theory but also the subtle nuances of narrative composition. He brought to his works the ability to create scenes that felt suspended in time, filled with emotion yet technically grounded. This blend of discipline and sentiment would define his major works in the decades to come. His education was not just a phase—it was the scaffold upon which his artistic career would be built.

Rise to Artistic Prominence

Pierre Auguste Cot made his debut at the Paris Salon in 1863, a pivotal moment that marked his entrance into the French art world. The Salon, being the most prestigious art exhibition in France, was a proving ground for painters seeking recognition from both critics and the public. Cot’s early entries were well-received, showcasing his ability to create graceful, classically inspired compositions. These early successes helped him secure portrait commissions and allowed him to build a reputation as an artist with both technical skill and aesthetic charm.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, Cot’s reputation grew steadily among the Parisian elite. He developed a following that included wealthy patrons who favored his sentimental and romantic style over the more experimental movements of the time. His works were often noted for their idealized beauty, serene expressions, and romanticized storytelling—all presented with impeccable craftsmanship. His paintings provided an appealing alternative to the political and emotional turmoil that pervaded much of modern art during this era.

From Salon Debuts to National Recognition

By 1874, Cot had achieved national recognition and was awarded the Legion of Honor, a distinction that confirmed his place among France’s most respected artists. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Salon, where his works were celebrated for their emotional warmth and visual harmony. Art dealers and critics praised his consistent quality and appeal, and his paintings were soon in demand across Europe. With each passing year, Cot solidified his image as a reliable purveyor of beauty and emotional depth.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, who craved revolution or abstraction, Cot remained dedicated to the classical ideals that had shaped his training. His rise was not fueled by controversy or rebellion but by a quiet consistency and an unfailing commitment to beauty. In a world beginning to fragment artistically and socially, Cot’s work served as a comforting reminder of permanence and grace. His reputation was not built overnight but carefully cultivated through diligence and talent.

Major Works and Their Meaning

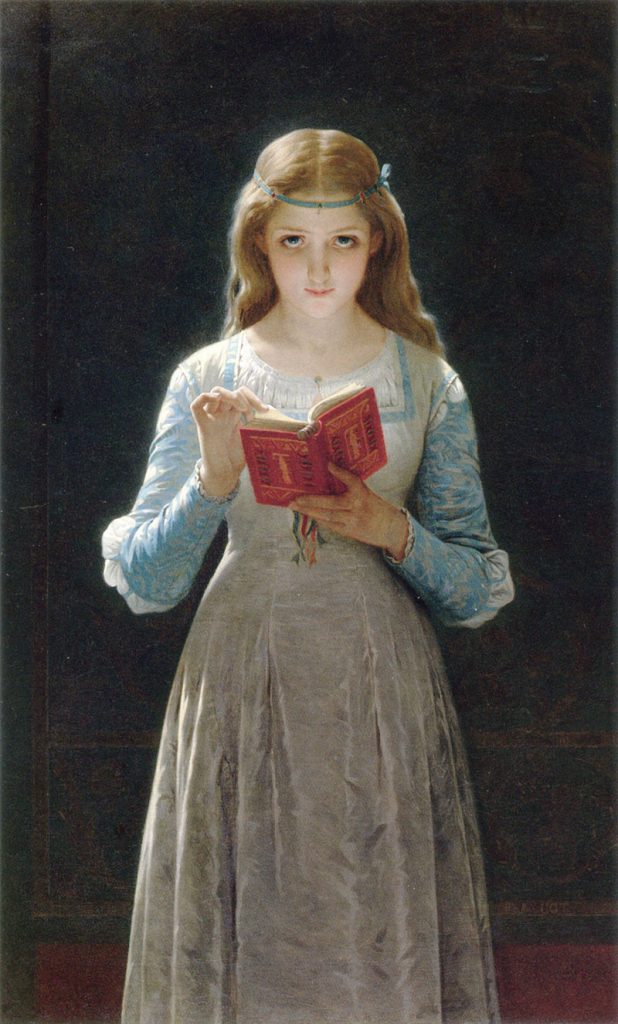

Two of Pierre Auguste Cot’s most celebrated paintings, Springtime (1873) and The Storm (1880), stand as pinnacles of 19th-century French Romanticism. Springtime depicts a young couple swinging through a shaded grove, their bodies entwined in a poetic balance of innocence and desire. The Storm, perhaps his most famous work, shows a youthful pair running through wind and rain, the girl’s garments whipped by the elements as she clings to her companion. These paintings exemplify Cot’s ability to infuse classical composition with a rich sense of movement and emotion.

Cot’s artistic signature is evident in the soft, pearlescent skin tones, fluid drapery, and glowing atmosphere that fill his canvases. His brushwork is tight yet expressive, capturing textures from delicate skin to storm-blown fabric with equal care. He favored balanced compositions, often placing his figures in natural settings filled with light and shadow, a technique learned from Bouguereau but given personal flair. In his hands, allegory and realism were not at odds but rather worked together to create images that felt timeless and emotionally resonant.

Interpreting “The Storm”: Love, Escape, and Movement

In The Storm, Cot presents not just a physical flight from weather, but a metaphorical flight into the unknown—a moment of youthful passion set against the chaos of nature. The painting resonates because it captures a universal moment: the tension between fear and exhilaration. It also exemplifies Cot’s mastery of anatomy and movement, with each muscle and fold of cloth animated by purpose. The couple’s expressions—urgent, alive, yet tender—draw viewers into a private narrative that feels both personal and mythic.

These works were not merely popular in their time; they have endured as icons of romantic visual art. Reproductions of Springtime and The Storm remain widespread in galleries and home décor alike, a testament to their emotional and aesthetic appeal. They represent a peak in Cot’s career, uniting technical skill with a profound, almost theatrical sense of story. In them, Cot proved that classical beauty and deep feeling could still captivate a modern audience.

Personal Life and Social Circle

In 1865, Pierre Auguste Cot married the daughter of Francis Goupil, a well-known French painter, establishing a bond that would enhance both his personal and professional life. Through this union, Cot became more deeply connected to the Goupil family, which also included the influential art dealer Adolphe Goupil. This connection helped increase Cot’s exposure in commercial circles and reinforced his place in the upper ranks of the French art scene. His marriage was not just a romantic partnership but also a strategic alliance that supported his growing career.

Cot’s social world included some of the most respected academic painters of his time. He maintained particularly close ties with William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who had been one of his mentors and remained a lifelong friend. The two men shared similar ideals regarding beauty, narrative, and form in painting. Their relationship extended beyond the canvas, involving shared exhibitions, studio visits, and intellectual discussions about the future of art.

A Life Among the Artistic Elite

Cot’s inclusion in the circles of elite Parisian society gave him access to powerful patrons, including aristocrats and prominent business figures. He was known to frequent salons and artistic gatherings where ideas were exchanged, but politics were often kept at bay. This environment suited Cot, who focused on art’s power to uplift and harmonize rather than provoke. His traditional values and focus on family and beauty resonated with conservative patrons looking for stability in art.

Though he remained private in many respects, Cot’s life was filled with warmth and strong personal relationships. He raised children with his wife, taught students, and mentored younger artists in the traditions of academic excellence. Far from being isolated, Cot thrived in the company of others who shared his respect for technique, decorum, and moral clarity. His personal life, like his art, was characterized by elegance, order, and purpose.

Late Career and Death

In the final decade of his life, Cot continued to enjoy success, regularly exhibiting at the Paris Salon and completing commissions for private collectors. Though his style remained consistent, subtle evolutions appeared in his use of color and lighting, which became increasingly radiant and atmospheric. Critics noted that Cot’s later works maintained the same emotional integrity while reaching new heights of technical refinement. He never wavered in his commitment to beauty and harmony, even as new artistic movements gained popularity.

Tragically, Pierre Auguste Cot’s promising life was cut short when he died suddenly on August 2, 1883, at the age of 46. His death shocked the artistic community and left several commissions incomplete. Cot was buried in the renowned Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, a resting place reserved for many of France’s most honored cultural figures. His passing marked the end of a career that, while brief, had a lasting impact on the artistic landscape of 19th-century France.

A Sudden End to a Promising Legacy

Cot’s early death created a gap in French painting, as he had become a leading voice for romantic academic art during a period of transformation. His death left admirers wondering what further masterpieces he might have produced had he lived into old age. Fellow artists and former students mourned his loss, speaking of his kindness, clarity of vision, and unwavering dedication to classical ideals. Memorial exhibitions were held in his honor, and his works continued to be displayed long after his death.

In the years immediately following his death, interest in Cot’s paintings remained strong, with continued reproduction of his most famous works. Though tastes would shift in the decades that followed, his contributions to the tradition of academic romanticism were never forgotten. Cot had built a body of work that resisted the chaos of modernism in favor of timeless beauty. His legacy, though interrupted, remained powerful and deeply respected.

Legacy and Artistic Influence

Though Pierre Auguste Cot died young, his influence stretched far beyond his short lifespan. Springtime and The Storm continued to be reproduced in prints, books, and later, museum postcards, making Cot’s imagery familiar even to those unfamiliar with his name. His emphasis on idealized love and narrative composition offered a counterpoint to the stark modernism that followed. Art historians have come to appreciate how Cot preserved the dignity of the classical tradition in a rapidly changing cultural climate.

His influence extended to painters seeking to revive romantic realism and those disillusioned with abstract art. Cot’s meticulous attention to form and emotion appealed to artists who valued order and craftsmanship over rebellion and experimentation. In this way, Cot became a quiet but enduring symbol of artistic integrity and traditional values. His paintings were often studied in art academies as examples of balance, technique, and evocative storytelling.

Cot in Modern Eyes: Romanticism Revisited

In recent years, Pierre Auguste Cot’s reputation has enjoyed a renaissance, particularly among conservative art historians and collectors who value the academic tradition. Museums have featured his works in retrospectives focused on romantic and classical art, placing him alongside peers like Bouguereau and Cabanel. Cot’s ability to evoke timeless themes with emotional resonance has given his works renewed importance. His art now serves not only as beautiful decoration but as a philosophical stance on what art should represent.

His inclusion in modern textbooks and exhibitions has prompted a reevaluation of academic painters previously overshadowed by the avant-garde. In Cot’s work, there is a return to the ideals of grace, virtue, and narrative clarity—elements often lost in postmodern experimentation. His legacy endures because it connects viewers to eternal truths through beauty and craft. In this way, Cot’s vision remains as relevant today as it was in the 19th century.

Key Takeaways

- Pierre Auguste Cot was born in 1837 in Bédarieux, France, and trained in classical art schools.

- He studied under great academic masters like Cabanel and Bouguereau in Paris.

- Cot’s major works, Springtime and The Storm, became enduring icons of romantic art.

- He gained national recognition and was awarded the Legion of Honor in 1874.

- Cot died prematurely in 1883, but his legacy in romantic realism continues to inspire.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is Pierre Auguste Cot best known for?

He is best known for his romantic paintings Springtime (1873) and The Storm (1880). - Where did Cot receive his artistic training?

Cot studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse and later in Paris. - Who were Cot’s artistic mentors?

His key mentors included Léon Cogniet, Alexandre Cabanel, and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. - What style of painting did Cot represent?

Cot was a leading figure in academic romanticism, favoring beauty, clarity, and emotional depth. - When and where did Cot die?

Pierre Auguste Cot died on August 2, 1883, and is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.