Maximilien Luce was one of the most technically skilled and morally grounded painters of late 19th and early 20th-century France. Born in 1858 and active until his death in 1941, Luce’s body of work bridges the rigorous discipline of Pointillism with a deep reverence for the common man. His paintings reflect a sincere admiration for honest labor and rural life, depicted with a refined sense of light and order. Though aligned with major movements of the day, he remained independent in both artistic style and ethical stance.

Luce belonged to the second generation of Neo-Impressionists, artists who expanded upon Georges Seurat’s optical theories while softening its rigidities. While Seurat pursued a nearly scientific approach, Luce made the method more humane, embracing vibrancy, warmth, and emotional truth. His commitment to portraying workers, rural scenery, and industrial scenes brought dignity to overlooked subjects. He neither pandered to politics nor compromised on aesthetic quality.

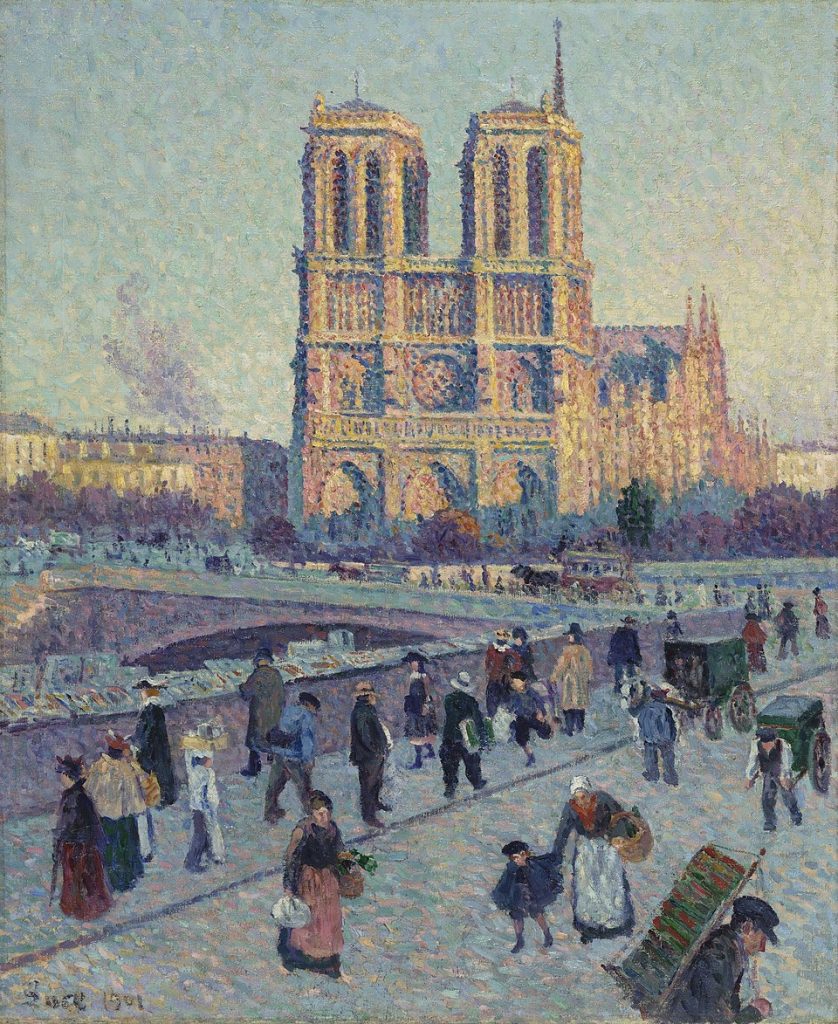

Over his long career, Luce remained a faithful chronicler of his country’s changing face. From the gas-lit streets of Paris to the sun-drenched hills of Rolleboise, his paintings capture both the pulse of modernity and the serenity of tradition. Even in an era that veered toward abstraction and radicalism, Luce stood for clarity, structure, and moral vision.

Though his name is not as widely known today as Monet or Van Gogh, Luce’s contributions are deeply respected among art historians and collectors. His works reside in major museums, his influence visible in the evolution of modern French painting. He represents a model of virtue in art: disciplined, honest, and luminous.

Early Years and Apprenticeship (1858–1877)

Maximilien Luce was born on March 13, 1858, in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris. His father, also named Maximilien, worked as a railway clerk, while his mother, Louise, ran a small laundry business. Raised in modest conditions, young Luce was surrounded by the working class and its daily rhythms. This early exposure to industrious, no-nonsense life would later become central to his artistic focus.

At the age of thirteen, Luce began an apprenticeship in wood engraving at the studio of Henri-Théophile Hildebrand. By 1872, he had mastered the technique, which required precision, patience, and a deep understanding of line. In addition to his technical training, Luce attended night classes at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs, studying under teachers who introduced him to classical draftsmanship. These dual foundations in craft and academic art provided him with a disciplined eye and a steady hand.

During this period, Luce also studied informally with Carolus-Duran, the celebrated portrait painter known for his loose brushwork and elegant compositions. Though Duran’s aristocratic subjects differed from Luce’s later themes, the experience gave Luce a grounding in figural structure and oil painting techniques. He absorbed these lessons while remaining committed to an unpretentious, realistic approach.

The political climate of France during Luce’s youth was marked by upheaval—the fall of the Second Empire in 1870, the Paris Commune in 1871, and the establishment of the Third Republic. These events did not radicalize him, but they sharpened his awareness of social structures and the value of order and peace. Even as a youth, he stood out for his seriousness and sense of duty.

Emerging Painter and Parisian Circles (1877–1886)

By 1877, Luce had begun to distance himself from engraving and devoted more energy to painting. He opened a studio in Montmartre and became immersed in the city’s artistic life. His early paintings reflect Impressionist influence, with scenes of Parisian life, portraits, and urban landscapes rendered in soft colors and broad strokes. Though these works were well executed, they lacked the distinctive clarity he would later develop.

Luce’s military service from 1879 to 1883 interrupted his artistic progress but also proved formative. Stationed in Brittany and later in Paris, he continued sketching and painting during his spare time. He also read extensively, absorbing ideas from scientific treatises and artistic journals. This intellectual foundation prepared him for the methodical theories of Seurat that would soon shape his direction.

After completing his service, Luce returned to Paris, where he exhibited in small galleries and built connections with fellow young artists. He began to refine his palette, increasingly interested in the effects of natural and artificial light. His brushwork grew more deliberate, and he sought more structure in his compositions.

By the mid-1880s, Luce had met members of the emerging Neo-Impressionist circle. This included Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Camille Pissarro. These friendships, particularly with Signac, would prove decisive. Luce began to see painting not only as a form of expression but also as a craft that could be improved through discipline and study.

Friendship with Seurat and Embrace of Neo-Impressionism (1886–1891)

Maximilien Luce met Georges Seurat in 1886, shortly after Seurat’s landmark painting “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” had shocked the Parisian art world. Luce quickly absorbed Seurat’s theories on Divisionism—the method of placing dots of complementary colors side by side to create optical harmony. Though Seurat was cool and analytical, Luce adapted the style with greater warmth and liveliness.

Luce’s first major works in the Neo-Impressionist style appeared between 1887 and 1889. They included city scenes such as “Rue Ravignan,” which featured delicate gradations of color and highly controlled compositions. He exhibited regularly at the Salon des Indépendants, the primary venue for artists who rejected academic conventions. His growing mastery of Pointillism distinguished him within the group.

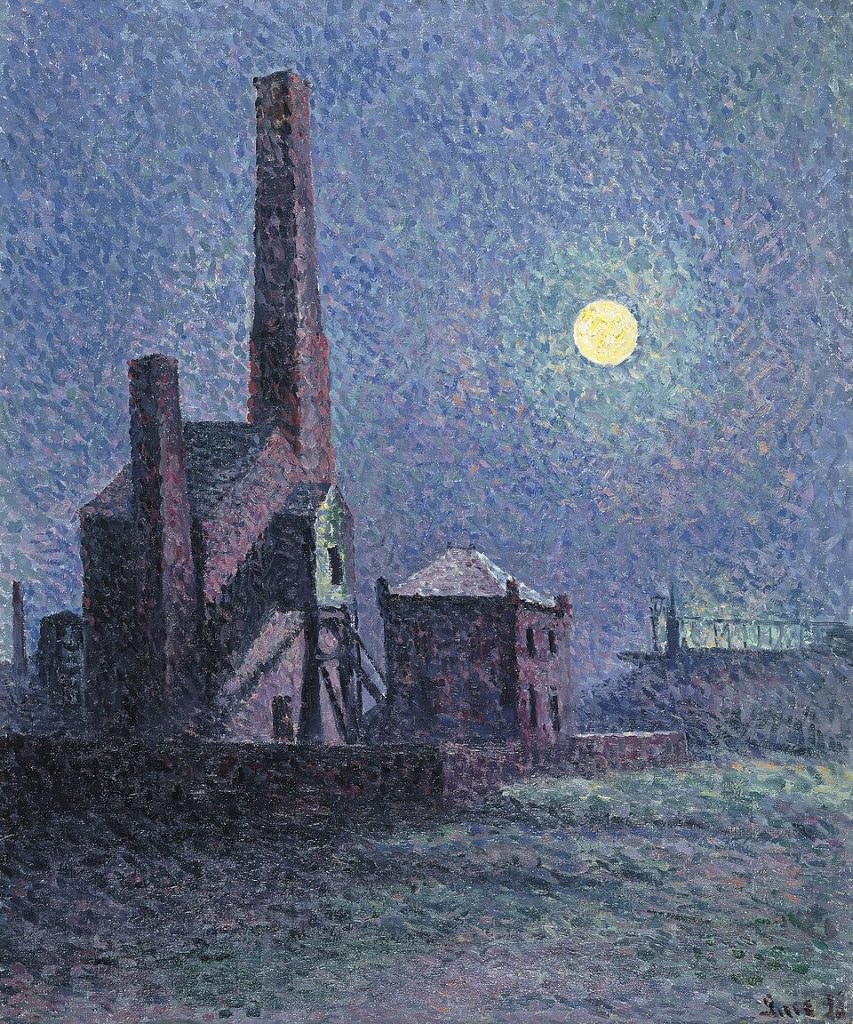

He also painted seascapes and labor scenes during this period, blending the new technique with socially conscious subject matter. Luce avoided political caricature, preferring to elevate the dignity of his subjects through artistic discipline. His painting “La Fonderie” (The Foundry) from 1890, for example, glows with internal heat while preserving the clear division of color.

His friendship with Paul Signac deepened during these years, leading to numerous artistic exchanges and mutual encouragement. Both artists saw light not only as a physical phenomenon but as a moral one: an emblem of clarity, virtue, and order. For Luce, Pointillism was not a gimmick but a way to make visible the structure of the world.

Social Awareness and Art of the Working Class (1890s)

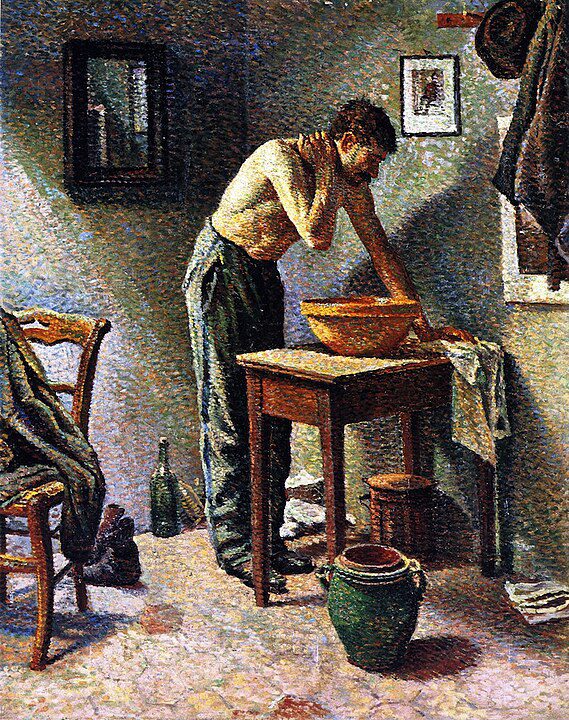

Throughout the 1890s, Luce became known for his portrayals of industrial workers and urban laborers. Unlike many contemporaries who romanticized poverty, Luce painted men at work with solemn grandeur. His paintings of blast furnaces, train yards, and road construction sites conveyed both physical exertion and aesthetic beauty. These subjects were chosen not to provoke pity but to honor perseverance.

In 1894, Luce was unjustly arrested and jailed for six weeks under suspicion of being involved in anarchist activities following the assassination of President Sadi Carnot. Though he had contributed illustrations to anarchist journals, he was not part of any plot. The incident damaged his reputation briefly but also confirmed his resolve to remain independent.

Major works from this period include The Steelworks at Charleroi (1895), The Railway Yard at Montparnasse (1893), and The Foundry (1894). These paintings used luminous dots and dashes to depict firelight, movement, and muscular labor. Luce brought classical structure to chaotic scenes, making them both believable and noble.

He also painted the lives of the urban poor in Saint-Denis and Montmartre, always with restraint and accuracy. His works never indulged in moral grandstanding. Instead, they conveyed a traditional sense of honor—that the lives of ordinary people mattered, and their world deserved faithful representation.

Personal Beliefs and Political Involvement

Luce was deeply sympathetic to ideals of justice and brotherhood but refused to serve political ideologies. His contributions to anarchist-leaning journals such as La Révolte and Le Père Peinard were artistic, not doctrinaire. He illustrated scenes of protest and hardship, yet kept his art rooted in balance, discipline, and truth.

He never joined a party or political movement, preferring moral clarity over partisanship. In an era where many artists were drawn into radical politics or state commissions, Luce charted a third path: art in service of truth, not ideology. He believed that painting should reveal the beauty of honest work and peaceful life.

Luce’s friendships included figures like Félix Fénéon, a critic and anarchist, and Theo van Rysselberghe, a Belgian painter and fellow Neo-Impressionist. These circles shaped his intellectual outlook but never dictated his brush. His work always retained a French sense of decorum, harmony, and clarity.

Though wrongly imprisoned once, Luce never used his experience to claim victimhood. Instead, he quietly returned to his easel and continued painting with humility. His sense of justice was rooted in order, not revolution.

Landscapes, Travel, and Rural Themes (1900–1914)

From 1900 onward, Luce devoted more attention to rural landscapes, particularly in Rolleboise along the Seine. He purchased a house there and painted the surrounding countryside in all seasons. These works captured sunlight on water, the quiet of village roads, and the rhythmic geometry of cultivated fields.

He also traveled to Brittany, Normandy, and southern France, painting ports, farms, and stone cottages. His landscapes from these regions show looser brushwork while retaining the chromatic brilliance of Neo-Impressionism. Paintings like The Seine at Rolleboise and Harvest in Normandy reflect a settled, almost pastoral beauty.

These years marked a withdrawal from urban chaos and a turn toward simplicity. His compositions became more serene, yet they remained grounded in strong design and thoughtful color. Even when depicting still waters or quiet orchards, he brought structure to every scene.

In many ways, this period represents the peak of Luce’s craftsmanship. He balanced light, form, and atmosphere with remarkable subtlety. These paintings reflect a man at peace, attentive to both divine order in nature and the quiet dignity of human life.

World War I and Return to Simplicity (1914–1920s)

The outbreak of World War I brought tragedy and disruption to France. Luce, now in his fifties, responded not with protest art or propaganda but with a retreat into contemplative subjects. His wartime works avoid depictions of battle, focusing instead on still lifes, portraits, and quiet village scenes.

His palette became more muted, and his compositions reflected introspection. Yet he never descended into despair or cynicism. Paintings like Interior at Rolleboise and Portrait of Madame Luce demonstrate warmth and poise.

After the war, he resumed travel within France and returned to painting workers, now rebuilding rather than demolishing. The laborers in his postwar works appear wearier, but still noble. He preserved their dignity without embellishment.

Though the art world moved toward Cubism, Surrealism, and abstraction, Luce remained true to his foundations. He continued exhibiting at the Salon des Indépendants and remained respected, though less fashionable. He never chased trends, preferring permanence over novelty.

Later Years and Honors (1930–1941)

In 1935, Luce was elected president of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, an honor that confirmed his place in French art. He served with dignity until 1940, when he resigned in protest over the group’s decision to exclude Jewish artists under pressure from the National Socialist regime. This final act underscored his lifetime commitment to justice and principle.

Despite age and health challenges, Luce continued to paint in Rolleboise and Paris. His final works retain the quiet integrity and structure that marked his career. He remained prolific until his last years, producing intimate portraits and calm landscapes.

Maximilien Luce died on February 6, 1941, in Paris, at the age of 82. His funeral was modest, attended by fellow artists and admirers who respected both his art and his character. He left behind hundreds of paintings, drawings, and engravings that captured a noble vision of France.

His death occurred during one of the darkest periods of French history, but his life had always pointed toward light. Even in decline and hardship, he had stood firm in truth and tradition.

Legacy, Museums, and Modern Reassessment

Luce’s works are now housed in major institutions across Europe and North America. The Musée d’Orsay in Paris holds a significant collection of his paintings, especially his urban and industrial scenes. The Petit Palais also preserves many of his landscapes and portraits. In the United States, his works can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

In recent decades, Luce has enjoyed a revival among scholars and collectors interested in Neo-Impressionism and social realism. Exhibitions in Paris, Brussels, and New York have reintroduced his work to new generations. Art historians now view him as a vital bridge between Seurat’s scientific vision and more human-centered 20th-century styles.

Critics praise Luce not only for his technique but also for his moral clarity. He painted with precision, avoided vanity, and stood firm in his principles. His devotion to structure, light, and truth serves as a corrective to much of modern art’s excess.

Luce’s life offers a model of artistic integrity grounded in tradition. His work reminds us that beauty and virtue can be aligned—that clarity of vision and strength of character still matter.