Georgia O’Keeffe, born on November 15, 1887, in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, emerged as one of the most significant and pioneering artists of the 20th century. Her distinctive contribution to modern art, especially within the realms of American modernism, is characterized by her unique interpretation of nature, landscapes, and flowers, which she transformed into powerful abstract images. O’Keeffe’s life was a testament to her unyielding dedication to her art, her exploration of innovative forms and colors, and her role in breaking boundaries for women in the arts.

O’Keeffe’s early education in art began at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1905-1906) and continued at the Art Students League in New York City (1907-1908), where she won a prize for a still-life oil painting. Despite this early success, O’Keeffe briefly abandoned the idea of a career as an artist, disillusioned by the limitations of the imitative style promoted by her instructors. This period of introspection was crucial, as it led to her eventual development of a personal and innovative style.

In 1912, O’Keeffe attended a summer class at the University of Virginia, where she was introduced to the ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow. Dow’s emphasis on creating art through the expression of personal ideas and feelings, rather than imitating reality, had a profound impact on O’Keeffe. This philosophy guided her work throughout her career, allowing her to explore abstraction and symbolism in ways that were deeply personal and innovative.

Enter Stieglitz

Her breakthrough came when Alfred Stieglitz, a renowned photographer and gallery owner, discovered her work in 1916. Stieglitz was instrumental in establishing O’Keeffe’s career, organizing her first solo show in 1917 at his 291 gallery in New York City. Their professional relationship evolved into a personal one, and they married in 1924. Stieglitz’s support and promotion of O’Keeffe’s work were pivotal, but O’Keeffe maintained her artistic independence, developing a style that was distinctly her own.

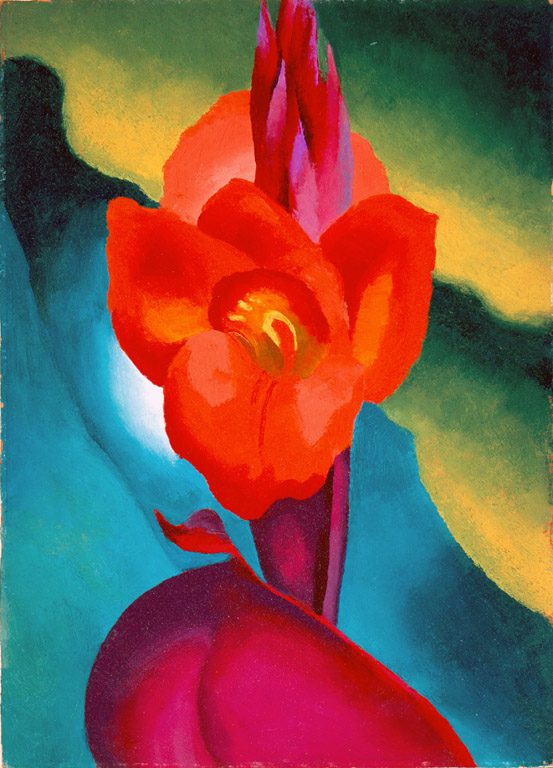

O’Keeffe’s work is best known for its enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. Beginning in the 1920s, her series of flower paintings, which magnified the flowers’ form to emphasize their shape and color, challenged traditional interpretations and invited viewers to see the natural world in a new light. These works, such as “Black Iris III” (1926) and “Red Canna” (1924), are celebrated for their boldness and originality, cementing O’Keeffe’s reputation as a pioneering modernist artist.

Southwest inspirations

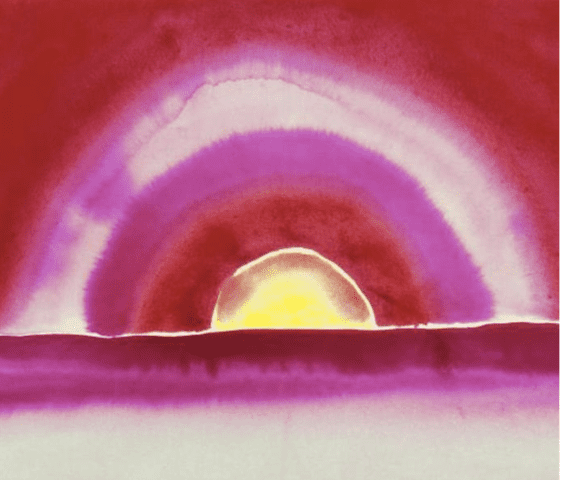

In 1929, O’Keeffe began spending part of the year in New Mexico, which profoundly influenced her work. The stark landscapes, vibrant colors, and unique cultural elements of the American Southwest inspired a new direction in O’Keeffe’s art. Her paintings from this period, such as “Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue” (1931) and “Ram’s Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills” (1935), reflect her deep connection to the land and its inherent beauty and spirituality.

Despite the personal and professional challenges O’Keeffe faced, including the complexities of her marriage to Stieglitz and her struggle for artistic independence, she remained dedicated to her vision. Her work continually evolved, reflecting her surroundings, experiences, and inner life. In 1946, following Stieglitz’s death, O’Keeffe moved permanently to New Mexico, where she lived until her death on March 6, 1986, at the age of 98.

O’Keeffe’s legacy extends beyond her expansive body of work. She is recognized for her role in the development of American modernism and for paving the way for future generations of women artists. Her dedication to her artistic vision, her exploration of abstraction, and her ability to convey the profound beauty of her environment have made her an enduring figure in art history. Georgia O’Keeffe’s work continues to inspire and captivate audiences, affirming her place as one of the most innovative and influential artists of the 20th century.