George Inness was born on May 1, 1825, in Newburgh, New York, as the fifth of thirteen children of John William Inness and his wife Clarissa Baldwin. His father was a farmer, and the family moved to Newark, New Jersey, when George was about five years old. Growing up in Newark, young George developed an early fascination for drawing and painting, even as his family expected a more conventional trade. His formal schooling was minimal, but this did not deter him — he was drawn to visual art from a young age.

When he was a teenager, around 1839, Inness studied for several months under an itinerant painter named John Jesse Barker, who had some modest skill and provided his first direct artistic instruction. As a young man he took up work in New York City as a map engraver, first with the firm Sherman & Smith and later with N. Currier (which would evolve into Currier & Ives). This engraving apprenticeship sharpened his attention to line and form, while giving him exposure to art reproductions — prints of European paintings that inspired him deeply. During this period, he began absorbing the look and feel of classical and biblical landscapes, even though his own opportunities were limited.

That early exposure — engraving, study under Barker, absorbing old-master prints — planted the seeds for his later commitment to landscape painting. By the mid-1840s he audited classes at the National Academy of Design in New York, studying work by prominent American landscape artists. In those formative years, Inness would recall the influence of earlier masters as a compass for his own stylistic ambitions. In 1848, at age 23, he opened his first studio in New York City, marking the formal beginning of his independent career as an artist.

These early years in Newark and New York — childhood in a large family, early desire to draw, exposure to engraving and European prints, modest study and a first studio — laid the foundation for what he would later become. The contrast between a humble upbringing and the aspirations of a young artist made his eventual success all the more striking. Inness’s sensitivity to natural detail and innate sense of composition began here, even before any formal European training.

Education and European Influence

In the early 1840s, while working as an engraver, Inness met the French-born landscape painter Régis François Gignoux, who had recently settled in New York. Gignoux’s presence offered Inness a bridge between his American surroundings and European landscape traditions — an opportunity to glimpse classical techniques and compositional approaches. Under Gignoux’s informal guidance, Inness began studying the landscape painting tradition of the Old Masters, referencing works by the likes of Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa. This experience widened his aspirations and reshaped his ambitions beyond engraving or simple local scenes.

Rome, Barbizon, and the Soul of Nature

In 1851 a patron, the New York entrepreneur Ogden Haggerty, sponsored Inness’s first grand trip to Europe. He spent about fifteen months in Rome and surrounding regions, absorbing the countryside, studying light and atmosphere, and deeply engaging with the ruins and landscapes of Italy. In 1852, he completed a painting titled A Bit of the Roman Aqueduct, which reflects his admiration for the classical descendants of landscape painting. This painting shows how he began integrating European compositional ideals — soft light, measured ruins, layered landscapes — into his own work.

After his time in Italy, Inness traveled to France in the early 1850s, where he encountered the emerging Barbizon School. The Barbizon painters emphasized mood, atmosphere, and a more expressive handling of nature than many of their predecessors. Inness absorbed their loose brushwork, darker tonalities, and emotional depth, and began to adapt these qualities to the American landscape. Although rooted in European technique, he remained committed to forging a distinctively American vision — seeking a style that merged European moodiness with the natural grandeur of the United States.

When he returned to America in 1853, Inness was no longer a young engraver or hopeful painter — he carried within him a matured vision. His European journey had armed him with deeper understanding of composition, light, and the spiritual resonance of landscape. Rather than purely copying European models, he now aimed to reinterpret American vistas with the emotional and philosophical weight he had learned abroad. This period marked a turning point: the beginning of Inness’s transformation from apprentice to landscape visionary.

Career Breakthrough and Hudson River School Ties

After returning from Europe, Inness began exhibiting his work in New York. His first public showing occurred in 1844 at the National Academy of Design — a modest beginning that nonetheless signaled acceptance in the New York art world. By 1848 he had established his own studio, but true recognition took time. Over the following years he developed his style, studied the works of earlier American masters, and honed a sensibility for light, mood, and landscape.

Inness’s work was often associated with the Hudson River School, a dominant force in 19th-century American landscape painting. Yet even early on, Inness differed from many of its members in tone and intent. Rather than striving for precise, dramatic detail and wild grandeur, he began to favor atmosphere and spiritual resonance. He painted not just land and sky, but emotion and essence — an inner vision of nature rather than a straightforward depiction.

One milestone came in the mid-1850s when Inness was commissioned by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad to document its progress in northeastern Pennsylvania. The commission resulted in works such as The Lackawanna Valley (c. 1855), a painting that juxtaposed early industrial enterprise with pastoral landscape. Rather than glorifying industrialization, Inness depicted the railroad as part of a broader natural panorama — the image carries subtle tension between progress and nature. This balance demonstrated his growing ability to weave landscape and meaning.

By the early 1860s, Inness had become recognized as a serious, original artist. Patronage from supporters like New York merchants and railway officials helped, but more importantly, his style of blending mood, landscape, and spiritual undertones set him apart. He achieved early critical success not because he followed trends, but because he redefined them. In those years, Inness began to find his voice — one that tempered realism with emotion, and described nature not only as it was, but as it felt.

Personal Life and Spiritual Beliefs

In 1849 Inness married Delia Miller, but tragically she died a few months later. In 1850 he remarried, this time to Elizabeth Abigail Hart; together they would have six children. Their family life gave Inness both stability and purpose, though his artistic ambitions often required long periods of absence on study trips. Among their children was George Inness Jr., born January 5, 1854 — a son who would later become a noted landscape and figure painter in his own right. The family’s artistic legacy thus extended into a second generation.

Even more significant than family were Inness’s spiritual and philosophical beliefs. During his formative European years — especially in Rome — he was introduced to the theology and writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. Swedenborg’s ideas about nature, spirituality, and the unseen deeply resonated with Inness. He came to believe that landscape painting could serve as a bridge between the visible world and spiritual truths. This inner conviction shaped his mature works, giving them a meditative, often mystical mood that transcended mere depiction of land.

As the years passed, Inness’s home base shifted to different places as his health, family, and work demands changed. From New York studios to periods spent in Massachusetts and New Jersey, he sought environments conducive to both family life and spiritual tranquility. His belief in art as a spiritual vehicle deepened. He viewed each painting not just as a scene, but as a meditation — a way to channel emotion, memory, and reverence for the natural world.

Through his marriage, his children (especially his son George Inness Jr.), and his spiritual convictions, Inness blended family, faith, and art. That fusion of personal and philosophical elements became a signature of his work. His landscapes began to reflect not only what he saw, but what he felt — an intimate inner world shaped by personal ties and spiritual longing.

Tonalism and Mature Style

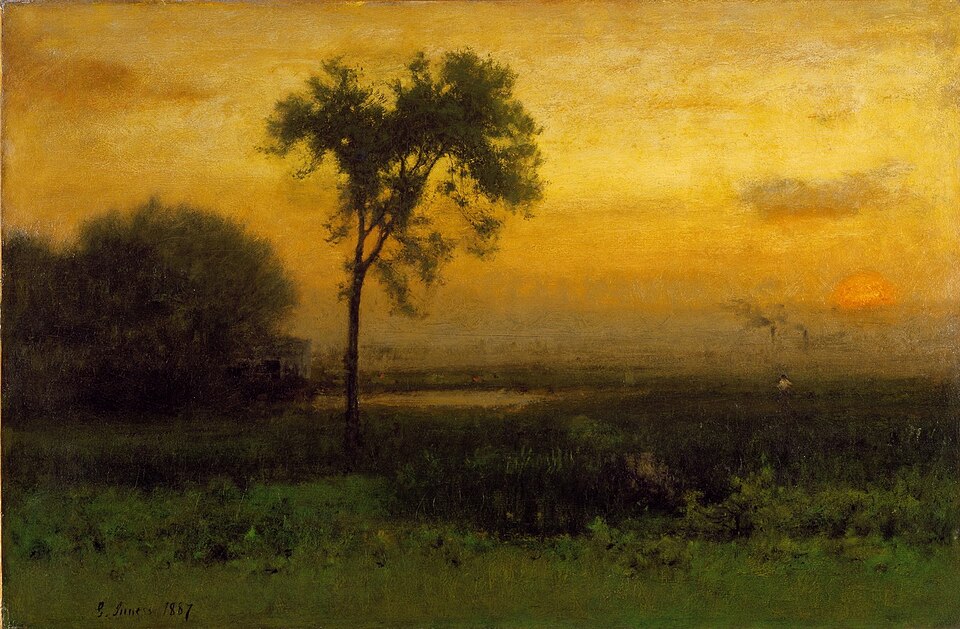

In the 1860s and 1870s, Inness began shifting away from the crisp realism associated with the Hudson River School toward what would become known as tonalism. Rather than sharply defined landscapes with dramatic detail, his paintings started to emphasize mood, harmony, and emotional resonance. The focus moved from topographical accuracy to atmosphere, from literal detail to poetic suggestion. His canvases began to breathe with light and shadow, soft edges, and a subtle palette that conveyed quiet introspection.

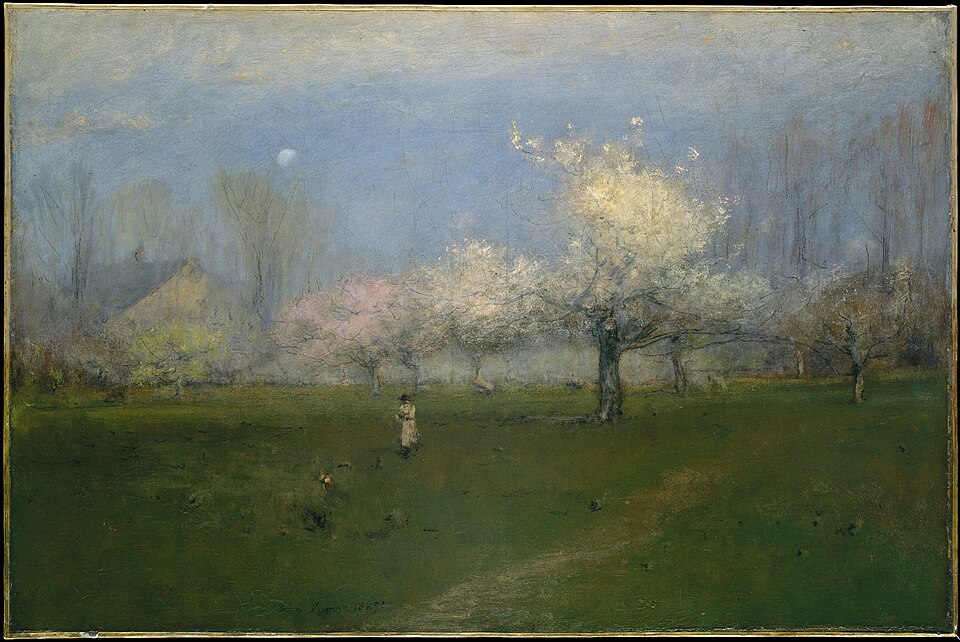

Works like the 1852 painting A Bit of the Roman Aqueduct show his early experimentation with classical European landscape motifs, but by the late 1860s his American landscapes began to reflect deeper tonal and spiritual concerns. Later masterpieces such as Autumn Oaks (1878) and Evening at Medfield, Massachusetts (1875) reveal how he used light, color, and composition to evoke inner mood rather than literal place. These paintings avoid the bold contrasts and dramatic light typical of earlier landscape traditions. Instead, they offer soft transitions of color and light, a whispered sense of time and place, calling on the viewer’s emotions and memory.

Inness’s mature style demonstrates his mastery of tonal harmony: he modulated foregrounds, middle grounds, and skies to evoke depth and feeling. He often painted at times of day when light softened — dawn, dusk, overcast skies — to create a sense of mystery, calm, or even spiritual resonance. His aim was not to freeze nature in a precise moment, but to suggest its transient mood and inner life. Through brushwork that softened edges and through glazes that muted detail, he invited viewers to feel nature rather than just see it.

This tonal, mood-driven approach distinguished Inness from many of his peers and placed him as a foundational figure in what would become known as American tonalism. His work bridged the romantic realism of the mid-19th century and the more expressive, introspective approach that would influence 20th-century landscape art. Inness showed that a painting could express not only external reality but also inner soul. His mature pieces remain powerful because they speak to the heart, not just the eye.

Later Years and Artistic Recognition

As his reputation grew, Inness remained active well into his later years. He continued to travel — including additional trips to Europe — and to refine his vision and technique with each journey. According to sources, his European trips during the 1870s and early 1880s further deepened his sense of atmosphere and light. He maintained studios, painted, and exhibited, even as he aged and weather grew more difficult. His dedication never wavered.

Inness spent his later years living in Montclair, New Jersey, where he took a studio adjacent to his home. Here he produced many of his late works, drawing on memory, nature, and spiritual inspiration. His 1891 painting Spring Blossoms, Montclair, New Jersey reflects this mature phase: soft light, gentle composition, an emotional tone rather than dramatic landscape. This quiet, thoughtful style became his signature in his final years.

His health was never robust; he reportedly suffered from “a fearful nervous disease,” possibly epilepsy, yet he persisted in his work. On August 3, 1894, while traveling in Scotland with his son George Inness Jr., Inness died at Bridge of Allan. He passed away at age 69. Later accounts suggest that he died while outdoors painting — a fitting, poignant end for a man whose life was devoted to the endless pursuit of nature’s beauty. The details of his final moments remain part of his legend, embodying his devotion.

In the decades following his death, Inness’s reputation continued to rise. Collectors and museums began to regard him as a foundational figure in American landscape painting. He was hailed not only for his technical skill but for his spiritual depth and emotional power. Exhibitions of his work grew in number, and critical scholarship re-evaluated his contribution. His later works in particular — atmospheric, moody, evocative — came to be seen as among his finest.

Enduring Legacy in American Art

George Inness is widely regarded as one of the most influential American painters of the nineteenth century. Many call him “the father of American landscape painting,” not because he founded a school, but because he transformed the very idea of what landscape art could express. He melded realism with mood, physical place with spiritual meaning, and grounded scenery with poetic soul. His landscapes became more than visual records — they became meditations on nature, existence, and inner life.

Museums across the United States now hold his works. His paintings appear in collections at institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and others, where they continue to inspire new generations. His influence extended beyond his own output: through his son George Inness Jr. and through the broader movement of tonalism, he shaped the direction of American landscape painting for decades after his death.

Today, art historians acknowledge Inness’s role as a bridge between the romantic realism of his time and the more introspective, expressive approaches that followed. His emphasis on atmosphere, emotion, and spiritual resonance paved the way for early modernist landscape sensibilities. He showed that painting could capture not just what the eye sees, but what the soul perceives.

Even more than technique or output — over 1,100 oil paintings and works on paper — Inness’s true legacy lies in his vision. He transformed American landscape painting into a language of feeling, memory, and reverence for the unseen. For anyone who studies American art, Inness remains a touchstone — a reminder that nature is not only scenery but spirit, and that a painter’s brush can reach far beyond the canvas.

Key Takeaways

- George Inness (1825–1894) was born in Newburgh, NY and raised in Newark, NJ; his early life combined modest origins with strong artistic ambition.

- His European studies (Rome, France) exposed him to classical landscape tradition and the Barbizon School, shaping his mature style blending American vistas with emotional, spiritual tone.

- He shifted from literal realism to atmospheric tonalism, favoring mood, light, and inner vision over detailed topography.

- Inness’s late works capture a poetic, almost mystical sense of nature; he continued to paint until his death in Scotland on August 3, 1894.

- His legacy endures in major American museums and through his influence on tonalism and later generations, including his son George Inness Jr.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who influenced George Inness’s early artistic development?

Inness’s early training included work under itinerant painter John Jesse Barker, engraving apprenticeships, brief study with Régis François Gignoux, and exposure to the works of Thomas Cole and Asher Durand. - What European traditions shaped Inness’s mature style?

During his travels in Italy and France (1851–early 1850s), Inness studied classical landscape painting and absorbed the moody, atmospheric approach of the Barbizon School, which led him away from strict realism toward tonalism. - What is tonalism and how did Inness use it?

Tonalism emphasizes mood, harmony, and subtle gradations of light and color rather than sharp detail; Inness used this to evoke emotional resonance and spiritual depth in his landscapes. - Did George Inness have children who became artists?

Yes — his son, George Inness Jr. (born January 5, 1854), grew up to become a noted landscape and figure painter, extending his father’s artistic legacy into a new generation. - Where can I see George Inness’s paintings today?

His works are held in major institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art, among others; many late tonal works remain influential landmarks in American art collections.