No city in Europe bears its history with such visible tension as Berlin. Its streets are not simply built over older strata—they often expose them, scarred and unhealed. While Berlin lacks the immediate grandeur of Rome or the deep medieval patina of Paris, its foundations run unexpectedly deep. Beneath the modern avenues and 19th-century boulevards lies a shadowy archaeology of power, trade, and cultural exchange. The artistic identity of Berlin begins not with German princes or Prussian armies, but with overlooked fragments of earlier civilizations.

Archaeological findings near the Spree River have unearthed evidence of Slavic settlements dating back over a thousand years. Even earlier, long before Berlin existed as a coherent political or geographic idea, the area was traversed by Roman traders and soldiers. Though Rome never formally annexed the land that would become Brandenburg, its influence left subtle traces—coins, weapons, ceramic vessels. These are not the monumental relics of empire, but the material flotsam of encounter: suggestive, elusive, strangely modern in their cross-cultural hybridity. In this earliest prehistory, Berlin already bore the marks of contact and collision, a theme that would come to define its art.

By the 13th century, the twin towns of Berlin and Cölln had emerged along the Spree. These were commercial hubs first and foremost—narrow alleys of fishermen, merchants, and craftsmen. Religious art dominated what little patronage existed. Painted wooden altarpieces, devotional sculptures in soft sandstone, and stained glass windows carried imported Gothic styles from Saxony and Bohemia into Berlin’s modest churches. Few of these early works survive the wars and fires that would plague the city, but their stylistic descendants remain visible in surviving fragments of the Nikolaikirche and the Church of St. Mary, where imported iconography mingled with local motifs, creating a vernacular Gothic that belonged to Berlin alone.

The Prussian gaze and early institutions

Berlin’s transformation from river town to artistic capital began in earnest in the 17th and 18th centuries, when the ambitions of the Electors of Brandenburg, soon to be Kings of Prussia, demanded a more coherent cultural policy. Art, once religious or municipal, became political. The ruling Hohenzollerns, seeking to centralize their power, poured resources into architectural projects that combined civic utility with dynastic prestige. The new royal city needed symbols—palaces, museums, statues—that could rival those of Vienna or Paris.

One of the most important shifts came not from a painter or sculptor, but from a librarian: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. In 1700, he co-founded the Prussian Academy of Sciences, which later evolved into the Akademie der Künste. The Academy brought together artists, architects, and intellectuals under a centralized framework of state-sponsored production and criticism. It was Berlin’s first formal gesture toward becoming not just a seat of government, but a place where art might be made, debated, and preserved on equal terms.

Under Frederick the Great, this ambition exploded into a city-wide program of cultural elevation. A lover of classical antiquity and French Rococo, Frederick’s patronage was inconsistent but consequential. His commissions produced ornate palaces like Sanssouci in nearby Potsdam, which merged Rococo flair with Enlightenment restraint. The city’s visual culture shifted from guild-based craftsmanship to a court-oriented aesthetic hierarchy. Painters such as Antoine Pesne were imported from France to paint airy mythologies and regal portraits, while sculptors like Johann Gottfried Schadow began adapting Neoclassical forms to a Prussian idiom—severe, Protestant, martial.

Museumsinsel and the politics of prestige

The 19th century ushered in what might be considered Berlin’s first true art-historical epoch, marked by both cultural confidence and intellectual anxiety. As Prussia rose in power and Germany began its march toward unification, Berlin’s rulers increasingly turned to museums as instruments of prestige, education, and soft power. This culminated in the creation of Museumsinsel—the Museum Island—an ensemble of neoclassical buildings in the heart of the city that embodied the imperial aspiration to gather, order, and display the world’s art.

The Altes Museum, designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and completed in 1830, was the centerpiece. Modeled after a Greek temple, it stood not just as a repository of ancient art, but as a monument to reason itself. Schinkel believed architecture could teach morality; he designed the museum as a civic space where the public would not simply view art, but internalize classical virtues through its harmonious proportions. Berlin, in this vision, would be a new Athens—a capital of culture as much as conquest.

By mid-century, the Neues Museum (1855), the Alte Nationalgalerie (1876), and the Bode Museum (1904) followed. Each reflected changing currents in historical thought and collecting philosophy. The Neues Museum, damaged heavily during World War II and later restored with haunting delicacy by David Chipperfield, brought Egyptian and early Mediterranean art to the fore, culminating in the installation of the bust of Nefertiti in 1924. That sculpture, poised in impossible calm amid the turbulence of Berlin’s interwar years, became a symbol of the city’s fraught relationship to antiquity—at once reverent and acquisitive.

These institutions did not merely collect art; they created narratives of civilization that justified Berlin’s imperial ambitions. Non-European works were often categorized according to colonial logics, displayed in ways that underscored the superiority of the European eye. Yet the very act of assembling these collections, and opening them to the public, also laid the groundwork for a more democratic form of cultural participation. Berliners came to expect that art belonged not just to kings or churches, but to citizens.

A revealing contradiction emerged. Even as the state sought to control the message of art—its historical significance, its national value—the city itself fostered a growing class of artists and thinkers who resisted that very control. The seeds of Berlin’s 20th-century avant-garde were planted in the salons and sketching studios of this earlier era, nourished by the proximity of state grandeur and individual defiance.

Berlin’s artistic foundations, then, are neither smooth nor symmetrical. They are layered—Roman coins beneath Prussian facades, Gothic saints beside Enlightenment temples. They speak of a city that has never been settled, in any sense of the word: not politically, not culturally, and certainly not artistically. The art of Berlin has always been born from friction. That tension would only deepen as the city moved into the modern age, dragging its ghosts with it.

Monarchy, Marble, and Masculinity: Art Under the Hohenzollerns

Frederick the Great’s Versailles envy

To understand the art of 18th- and early 19th-century Berlin, one must first understand the personality—and contradictions—of Frederick II of Prussia, known to history as Frederick the Great. A man of military precision and philosophical pretense, he was equally enamored of French Enlightenment rationalism and the trappings of absolute monarchy. In art, as in statecraft, Frederick viewed beauty as a means of control, a well-ordered facade masking inner volatility. His reign (1740–1786) left an indelible mark not only on the political landscape of Berlin, but on its cultural and visual identity.

Frederick loathed the ostentatious heaviness of the German Baroque, which he associated with backwardness and Catholic excess. Instead, he turned to France—not merely for its aesthetic models, but for its thinkers, musicians, and architects. His court painter, Antoine Pesne, brought a decorative softness and courtly sophistication to Berlin portraiture, replacing dour Protestant stiffness with something closer to the theatrical elegance of Versailles. But Frederick’s ambition extended beyond painting. Architecture became his preferred instrument of legacy.

Sanssouci Palace, constructed between 1745 and 1747 in Potsdam, stands as a synthesis of this vision. Often described as the “Prussian Versailles,” it lacks the overwhelming scale of its French counterpart but makes up for it in elegance and clarity. The Rococo curves and garden symmetries mask a deep ideological project. This was not simply a retreat; it was a stage for enlightened monarchy, where philosophy and taste were meant to converge in a vision of benevolent rule. Voltaire lived there briefly, surrounded by paintings and sculpture that flattered both king and guest. Marble busts of Roman emperors watched over salons where reason and rhetoric were meant to triumph.

Yet Frederick’s ideal of refinement was inseparable from a deeper authoritarian impulse. The art he commissioned often presented an image of control that was more wish than reality. Mythological themes proliferated—Mars, Minerva, Apollo—depicting the king as both warrior and sage. Sculpture became a key medium for this symbolic layering. Figures like Friedrich Christian Glume and Johann David Räntz produced works that wrapped the king’s persona in a classical aura, projecting strength through antiquity’s borrowed authority.

The result was a Berlin in aesthetic tension. On one hand, the city’s intellectual life flourished. Enlightenment thinkers found patronage and protection. On the other, the visual arts were increasingly harnessed to maintain the fiction of order. A city that welcomed philosophy was also one that choreographed every column and canvas to reinforce dynastic might.

Schinkel and the classical turn

By the early 19th century, a new figure emerged to reshape Berlin’s aesthetic identity with greater restraint and moral clarity. Karl Friedrich Schinkel, architect, painter, and theorist, became the visual conscience of a city in transition. Following the Napoleonic Wars, Berlin was traumatized, financially strained, and politically uncertain. Schinkel responded with buildings that combined classical balance with Protestant sobriety—a Neoclassicism of steel nerves rather than marble warmth.

His Altes Museum, completed in 1830, still stands as a defining landmark on Museumsinsel. Inspired by the Greek Stoa and the Roman Pantheon, the museum did not seek to overwhelm; it sought to elevate. Schinkel’s use of columns and open courtyards reflected his belief that public architecture should instruct as much as impress. The museum’s purpose was moral as well as cultural—it was to educate citizens in the values of antiquity, instill civic virtue, and embody the harmony between reason and beauty.

Elsewhere, Schinkel designed the Schauspielhaus (now the Konzerthaus) and numerous civic buildings that redefined Berlin’s skyline. His rigorously symmetrical facades and refined ornamentation eschewed the decorative excesses of previous generations. Where Rococo had whispered privilege, Schinkel’s Neoclassicism spoke of discipline and duty.

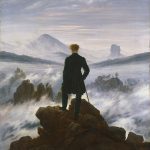

Yet beneath this formality lay a deeply romantic temperament. In his paintings—often idealized landscapes or allegorical fantasies—Schinkel gave space to yearning and metaphysical unease. His architectural vision may have been rational, but his inner world remained haunted by the instability of modern life. This duality made him uniquely suited to Berlin: a city perpetually poised between grandeur and collapse.

Schinkel’s influence extended beyond stone and pigment. He shaped how Berliners thought about their city—as a site not only of governance but of cultural mission. His pupils, including Friedrich August Stüler and Hermann Friedrich Waesemann, would carry this vision forward into the next generation, producing iconic structures like the Neues Museum and the Rotes Rathaus.

Berlin was no longer simply a court city. It had become a cultural capital, albeit one whose official art still bore the unmistakable scent of masculine order and martial discipline.

Court painters, allegory, and the aesthetics of control

Throughout the Hohenzollern era, painting in Berlin remained a secondary art, often overshadowed by architecture and sculpture. Yet its role within the court and academy was no less significant. From Pesne’s flattering oils to Eduard Daege’s allegorical murals, painting served the dual function of decor and propaganda—never quite autonomous, always in the service of state ideals.

Academic painting in Berlin during the early 19th century was characterized by a preference for clarity, moralizing content, and historical gravitas. Artists trained at the Prussian Academy of Arts were expected to uphold standards that reflected the values of the state: discipline, patriotism, masculine virtue. Even biblical or mythological scenes were rendered with a kind of Lutheran severity, drained of sensuality, bathed in cool light. Allegory was the dominant language—battle as virtue, wisdom as woman, peace as empire.

Notable figures included Wilhelm von Kaulbach, whose vast murals in the Neues Museum attempted to map the progress of human civilization through epic narrative. The ambition was Wagnerian in scope, yet constrained by rigid symbolic frameworks. Every gesture, every color, carried an assigned meaning. Nothing was spontaneous.

This control extended to representations of gender. While women appeared in court painting—most often as muses, goddesses, or allegorical types—they rarely occupied the role of artist or subject in their own right. Masculinity was sculptural, muscular, and dominant; femininity was either decorative or moralizing. Exceptions were few. The powerful, intimate etchings of early female artists like Caroline Bardua found limited public exposure. Art by women was tolerated, even encouraged, but almost never canonized.

Still, the visual culture of Berlin in this period cannot be dismissed as sterile. Its order was not without tension. Behind the tidy allegories and marble facades, anxieties simmered: about revolution, about nationalism, about the shifting grounds of power. These were not just political fears but aesthetic ones. The tightly controlled style of the Hohenzollern era masked deep discomfort with change. The art of Berlin, like its politics, was a performance of stability haunted by instability.

That performance would soon unravel. As Berlin entered the final decades of the 19th century, a new generation of artists began to reject the constraints of academic taste and imperial iconography. The stage was set for rebellion. But before expressionism could emerge, before the cabarets and collages and confrontations of the 20th century, Berlin had to first confront its own cultural inertia. The uniform facades had to crack.

Berlin Secession and the Fight for Modernism

Max Liebermann and the break from academicism

The year was 1898, and a quiet insurrection was underway in Berlin’s art world. A group of painters, sculptors, and graphic artists—frustrated by the rigid hierarchies of the state-run Prussian Academy of Arts—formally broke away to form the Berliner Secession. What they demanded was not merely freedom of style, but freedom from the dead weight of academic gatekeeping. In a city increasingly defined by industrial expansion, social unrest, and intellectual ferment, these artists saw the official aesthetic of mythological allegory and historicist piety as not just outdated, but dishonest.

At the center of this rupture stood Max Liebermann, a Berlin native and the son of a wealthy Jewish textile merchant. Trained in Weimar and Paris, Liebermann had absorbed the tonal realism of the Dutch masters and the loose brushwork of French Impressionism. His early paintings of peasants and workers were met with condescension by the academic establishment, which saw them as lacking in idealism and narrative clarity. But it was precisely this ambiguity—this refusal to moralize or romanticize—that made Liebermann’s work so radical in Berlin.

When he was elected the first president of the Secession, Liebermann used his considerable influence to bring international currents into the city. He exhibited works by French Impressionists, Scandinavian Symbolists, and Belgian modernists, while encouraging younger German artists to reject the academic straitjacket. The Secessionsstil that developed in Berlin was never a single style, but a broad alliance united by opposition: to state control, to historicist pastiche, to the sanctification of the past at the expense of the present.

What made the Berlin Secession particularly potent was its urbanity. Unlike the Vienna Secession, with its metaphysical flourishes and Art Nouveau fantasies, Berlin’s modernism was grounded in the reality of the city: its factories, tenements, cafés, and streets. Painters like Lesser Ury, Walter Leistikow, and Lovis Corinth captured not ideal beauty but atmospheric unease—fog-drenched train stations, bourgeois interiors tinged with boredom, nudes rendered with unflattering honesty. They replaced the allegorical with the psychological, the grand with the intimate.

The Secession, though founded in protest, soon became a powerful institution of its own. But its influence was always conditional, always under threat. Internal schisms—between Liebermann’s Impressionist circle and the more radical Expressionists—eventually led to a second rupture in 1910. Still, the seeds had been sown. Berlin had become a city where modernism was not a foreign import, but a native voice.

Käthe Kollwitz, Ernst Barlach, and the moral impulse

While the Secession was redefining taste and exhibition politics, another current of modernism was taking shape—one less concerned with style and more with substance. Berlin’s fin-de-siècle art scene was marked not only by aesthetic revolt, but by moral urgency. Nowhere was this more visible than in the work of Käthe Kollwitz.

Born in Königsberg but long based in Berlin, Kollwitz trained at women’s academies and studied engraving under the realist Karl Stauffer-Bern. Her early work, deeply influenced by the writings of Émile Zola and the plight of the urban poor, rejected both academic prettiness and decorative modernism. Instead, she turned to lithography, woodcut, and etching to depict the raw experiences of hunger, grief, and resistance. Her series The Weavers (1893–1897) and The Peasant War (1902–1908) gave visual voice to the anonymous victims of industrial and political violence—often women, often mothers.

In 1903, Kollwitz became the first woman elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts, though she would be expelled by the National Socialists three decades later. Her influence was not merely artistic but ethical. She believed art should serve the truth of human suffering, and that beauty without compassion was vanity. Even when her style changed—moving from realism to a more sculptural, symbolic language—her commitment to justice remained unwavering.

Another kindred spirit, though working in different mediums, was Ernst Barlach. A sculptor, dramatist, and expressionist, Barlach created figures that seemed hewn from sorrow itself: bowed, emaciated, introspective. His memorials to the dead of World War I—especially The Magdeburg Cenotaph and The Floating Angel in Güstrow Cathedral—offered no heroics, only lamentation. Though never as embedded in Berlin’s artistic institutions as Kollwitz, Barlach’s work circulated widely in the city, and his moral seriousness struck a deep chord in the wake of war.

These artists, though stylistically distinct from the Secession proper, were part of the same ecosystem of resistance. Their influence endured not just in galleries, but in the cultural memory of Berlin—a city that, time and again, would return to themes of loss, protest, and reckoning.

The politics of taste and the state

The rise of the Berlin Secession coincided with a broader political crisis in Germany’s cultural institutions. As Wilhelmine Germany marched toward militarism and colonial expansion, official art policy became increasingly prescriptive. The Kaiser himself took a direct interest in artistic matters, condemning modernism as degenerate and praising “heroic realism” as the appropriate style for a proud empire.

In 1901, Wilhelm II famously denounced the Secession’s exhibitions as “artistic Bolshevism” and demanded that state-funded museums adhere to “healthy national values.” The Berlin National Gallery, under director Hugo von Tschudi, briefly defied this mandate by acquiring works by Manet, Cézanne, and Rodin. But Tschudi was soon forced out, and a new era of cultural censorship began.

Yet suppression often breeds innovation. Artists excluded from the mainstream sought alternative spaces—commercial galleries like Paul Cassirer’s, private salons, print journals such as Pan and Der Sturm. These venues nurtured not only painters but poets, playwrights, and musicians. Berlin’s cultural life fractured, but in that fracture it began to glow.

By the eve of World War I, the battle lines were drawn. On one side stood the institutions of empire: museums filled with nationalist allegory, academies steeped in decorum. On the other stood a ragged, electrified vanguard of modernists, radicals, and moralists who had made Berlin their home—not because it welcomed them, but because it was the one place where even rejection could be turned into momentum.

The Berlin Secession was more than an art movement. It was an act of civic defiance, a declaration that art must respond to its time or risk becoming a museum piece in its own life. In challenging the aesthetics of empire, these artists gave Berlin a new visual vocabulary—one that would only grow more urgent in the chaos that followed the Great War.

Dada Arrives in Tatters: Berlin Between the Wars

Grosz, Heartfield, and the theatre of rage

When the guns of the First World War finally fell silent in November 1918, Berlin was not at peace. The monarchy had collapsed, revolution simmered in the streets, and the city seethed with political uncertainty. Out of this turmoil erupted an art movement that did not seek to soothe or elevate—it aimed to attack, mock, and annihilate. Berlin Dada, forged in the chaotic aftermath of war, was less a style than a sustained howl of contempt. It viewed reason as a farce, tradition as hypocrisy, and art itself as complicit in the moral bankruptcy of modern life.

At the heart of Berlin Dada were two incendiary figures: George Grosz and John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld). Grosz had already served in the army before being discharged as psychologically unfit. His drawings from the war years were caustic, carnivalesque scenes of mutilated veterans, corpulent capitalists, and leering bureaucrats. Influenced by Expressionism but stripped of its mysticism, Grosz’s work was a graphic indictment of Weimar hypocrisy. His 1920 portfolio Gott mit uns (“God with us”) mocked the military, church, and judiciary so savagely that he was put on trial for blasphemy.

Heartfield, meanwhile, took the emerging technique of photomontage—cutting and reassembling photographic fragments—and weaponized it. Trained in conventional illustration, he abandoned traditional techniques in favor of radical collage. He changed his name from Helmut Herzfeld to protest Germany’s jingoism and began using art to expose the grotesque contradictions of nationalism, capitalism, and media. Working for Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag) and later Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIZ), Heartfield created some of the most potent anti-fascist imagery of the 20th century: swastikas made of axes, generals with pig snouts, and nationalist slogans literally turned upside down.

Berlin Dada was not just about aesthetic rebellion. It was performative, theatrical, and often deeply confrontational. In 1920, the First International Dada Fair took place in a Berlin gallery, featuring slogans like “Art is dead – long live the machine art of Tatlin” and grotesque mannequins hanging from the ceiling. It was a public provocation, a staged demolition of cultural pieties. Police raided the show. Some of the artists were fined, others jailed. But the damage was done. Respectability had been forfeited in favor of rage.

What distinguished Berlin Dada from its cousins in Zurich or Paris was its intense politicization. Where Zurich Dada reveled in absurdity and linguistic play, Berlin’s version was a political weapon, forged in the heat of class struggle and revolutionary defeat. It was brutal, satirical, and—at times—nihilistic. It did not ask for beauty or understanding. It spat in the face of both.

Cabarets, photomontage, and collapse

Beyond the galleries and pamphlets, Berlin Dada flourished in the city’s nightlife—cabarets, basements, and smoky performance spaces where art and revolution bled into each other. In venues like Schall und Rauch (“Sound and Smoke”) or the Theater des Neuen, artists, dancers, and anarchists staged evenings of chaos: masked performances, grotesque recitations, anti-war songs shouted over clanging piano chords. These were not entertainments. They were public breakdowns enacted as art.

Artists such as Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann, key members of the Dada circle, extended the revolution of form. Höch’s photomontages in particular—assembled from fashion magazines, newspapers, and technical manuals—exposed the absurdity of gender roles and the consumerism infecting Weimar culture. Her 1919 collage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany is a chaotic explosion of faces, machinery, bodies, and slogans—a visual scream that captures the spirit of an age unhinged.

Hausmann, who described himself as a “mechanical head,” produced optophonetic poetry and crude sculptures out of typewriters and found materials. His critiques were aimed not just at politics, but at language, logic, and even the concept of individuality. For him and his peers, postwar society was not merely sick—it was terminal.

This radical art, however, was not made in a vacuum. Berlin in the early 1920s was in the grip of hyperinflation, street violence, and paramilitary brutality. The Spartacist uprising had been crushed. Rosa Luxemburg was dead. The city trembled between utopia and collapse. Dada reflected this condition, not just stylistically but ontologically. It was the art of a world unraveling.

And yet, amid this bleakness, Berlin Dada achieved something remarkable: it redefined what art could be. It expanded the field of possibility to include pamphlets, posters, staged protests, and photomontages pinned to telephone poles. It anticipated future movements—Fluxus, Situationism, punk—with its fusion of politics and absurdity. And it left behind a body of work that still burns with acid.

Degenerate or defiant? The state strikes back

Despite its notoriety, Berlin Dada’s institutional footprint was always precarious. Unlike the more marketable strains of Expressionism or the emerging New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), Dada had little gallery support and even less tolerance from authorities. Its artists were targeted not only by conservative critics but by the judiciary itself. Grosz was repeatedly hauled before courts. Heartfield was attacked in the press. Many of their works were censored, confiscated, or destroyed.

As the decade wore on, and the fragile Weimar Republic gave way to authoritarian consolidation, the avant-garde was increasingly labeled subversive, immoral, or foreign. With the rise of National Socialism, this hostility crystallized into a full-blown campaign of artistic purification. In 1937, the infamous Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate Art”) exhibition in Munich included works by Grosz, Höch, Hausmann, and dozens of their peers. Dada, once dismissed as nonsense, was now denounced as a threat to the racial and moral order.

Many Berlin Dadaists fled. Heartfield escaped to Czechoslovakia, then England. Grosz emigrated to the United States. Höch, remarkably, remained in Germany, surviving the war in seclusion near Berlin, continuing to create collages in secret. Dada, officially condemned, lived on underground.

But repression did not erase its impact. The techniques pioneered by Berlin Dada—photomontage, performance protest, typographic subversion—would echo throughout 20th-century art. Its legacy would appear in the anti-war posters of the 1960s, the guerrilla feminism of the Guerrilla Girls, and the anti-capitalist critiques of contemporary activist art. Even the iconoclastic spirit of punk, with its scissored magazines and cut-up manifestos, owes a debt to Dada’s Berlin laboratory.

In the end, Dada in Berlin did not die. It exploded. And the fragments are still sharp.

Art and the National Socialist Catastrophe

Purges, exiles, and lost studios

When the National Socialist regime seized power in January 1933, Berlin’s status as a hub of artistic radicalism collapsed overnight. The new government, intolerant of ambiguity and hostile to dissent in any form, moved quickly to dismantle the city’s modernist infrastructure. Museums, galleries, studios, and academies were purged of “undesirable” influences—particularly anything that deviated from the regime’s authoritarian aesthetic ideals or challenged its political mythology. For Berlin’s artists, especially those who were Jewish, leftist, or modernist, the city that had once nurtured their experiments became a zone of surveillance, denunciation, and terror.

The Prussian Academy of Arts, which had once boasted figures like Max Liebermann, Käthe Kollwitz, and Otto Dix among its members, was systematically restructured. Liebermann, already in his eighties and in declining health, resigned from the Academy in silent protest shortly after Hitler’s appointment. He would die in 1935, his name unspoken by the state, and his funeral largely unattended by the Berlin institutions he had once helped shape. Kollwitz, a pacifist and socialist, was expelled from the Academy in the same year. While allowed to remain in Berlin, she was forbidden from exhibiting, publishing, or holding official posts. Her studio in Prenzlauer Berg became a private shrine of quiet resistance.

Others had no choice but to flee. George Grosz left for New York just days after Hitler’s rise. John Heartfield escaped to Prague, then to London. Paul Citroen and Rudolf Schlichter vanished from public life. Dozens of Berlin’s Jewish artists—sculptors, photographers, designers, printmakers—were rounded up, interrogated, and forced into exile if they could afford it. Those who couldn’t often vanished into the growing machinery of repression. The vibrant, dissonant, and fearless art scene that had defined the Weimar era was decapitated in less than a year.

What was lost cannot be fully calculated. Studios were emptied. Archives destroyed. Works confiscated and burned. Some artists destroyed their own pieces in despair or self-preservation. Others kept painting in secret, their canvases hidden beneath floorboards or behind false walls. A few—too old to run, too proud to hide—stayed and were killed.

Berlin, once an unruly capital of artistic confrontation, was reduced to a city of official parades and monumental kitsch.

The twisted idealism of Arno Breker

Yet art did not disappear under the National Socialists—it was co-opted. The regime understood its power and wielded it with calculated intent. In place of modernist experimentation came an official visual style built on pseudo-classical grandeur and racialized mythology. The ideal was not the individual, but the Volk; not emotion, but order; not ambiguity, but dogma.

The sculptor Arno Breker became the regime’s artistic darling. A technically brilliant craftsman with a background in French Neoclassicism and Italian Renaissance sculpture, Breker adapted his skill to serve the propaganda needs of the Reich. His colossal, anatomically idealized male nudes—bronzed, emotionless, poised—were not simply statues but embodiments of the state’s racial ideology. Commissioned by Hitler himself, Breker’s works were displayed prominently in the new Reich Chancellery and at the Berlin Olympic Stadium, giving form to the regime’s fantasies of strength, purity, and destiny.

Though Breker later claimed to have been apolitical, his role in Berlin’s cultural apparatus was anything but passive. He traveled in elite circles, received vast sums from the state, and was instrumental in designing the aesthetics of the so-called Welthauptstadt Germania—Albert Speer’s plan to remake Berlin as the global capital of the future. Breker’s art, towering and chilling, helped legitimize a system built on repression and genocide. His marble bodies were monuments not to beauty, but to brutality.

Architecture followed suit. Speer’s designs for Berlin were a monstrous echo of classical Rome, scaled for totalitarian control. Streets were widened into boulevards for military parades; buildings swelled into fortresses of granite and iron. Though only fragments of Germania were ever realized—war, ironically, saved Berlin from full transformation—the vision itself was clear: art as domination, the city as stage, the citizen as ornament.

Painting, too, was reduced to caricature. Heroic farmers, radiant Aryan mothers, idealized soldiers—these were the sanctioned subjects. Modernism was labeled degenerate, and its works were confiscated en masse. In 1937, the state staged the notorious Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate Art”) exhibition in Munich, which later toured the Reich. Featuring over 600 works by artists such as Grosz, Dix, Kirchner, and Kandinsky, the exhibition was designed to incite scorn and ridicule. Crowds jeered, spat, and sometimes wept.

But even in condemnation, these works reached a new audience—some for the first time.

What was saved, and who saved it?

As Berlin descended into war, a quiet resistance to cultural annihilation emerged. Museum curators, librarians, archivists, and private citizens risked their positions—and sometimes their lives—to protect artworks marked for destruction. In the basements of the Nationalgalerie, in the cellars of the Berlin State Library, even in abandoned subway tunnels, works by van Gogh, Munch, Nolde, and Beckmann were hidden behind false walls or miscatalogued as “missing.” The very architecture of Berlin became a map of secrets.

One figure often overlooked is Ludwig Justi, the former director of the National Gallery, dismissed by the Nazis in 1933 for his support of modern art. Though publicly silent during the regime, Justi remained in Berlin, cultivating quiet networks of preservation. Another was Carl Georg Heise, director of the Lübeck Museum, who helped smuggle banned works to neutral countries. Artists themselves, such as Höch, buried their pieces in the ground or disguised them as decorative panels. Others turned to miniature forms—postcards, sketchbooks, linocuts—that could be hidden or carried in a coat.

A handful of art dealers, too, engaged in careful duplicity. Some sold approved art to fund the escape of modernist colleagues. Others forged documents or created false provenance records to protect “degenerate” pieces from confiscation. These acts were small, often anonymous, and nearly always at odds with official Berlin. But they mattered.

When the Allies finally entered Berlin in 1945, they found a city reduced to rubble, its cultural institutions shattered. Yet amid the ruins, fragments of its lost art survived: broken statues, scorched canvases, charred portfolios. These remnants—damaged, incomplete, but undeniably present—became the basis of Berlin’s postwar reckoning.

The Nazi era did not merely interrupt the city’s artistic history. It severed it, warped it, forced it underground. And yet, like the city itself, Berlin’s art did not vanish. It fractured, adapted, waited. In the decades that followed, a new generation would be forced to ask: What can be built on a field of ashes?

Divided Aesthetics: Cold War Berlin’s Two Art Worlds

Socialist realism in the East

When Berlin was split after 1945, its art world—like its streets and rail lines—was carved in two. The eastern half, administered by the Soviet Union, became the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and with that came a tightly managed cultural policy shaped by Soviet doctrine. The state endorsed a single aesthetic ideology: Socialist Realism. Art was to be clear, uplifting, rooted in the life of the people, and above all, in service to socialism.

This directive affected every aspect of visual culture in East Berlin. From paintings and posters to sculpture and public murals, the ideal artist was not an individualist or critic but a craftsman of ideology. Art was meant to educate, not provoke. It should show construction, not collapse. The farmer, factory worker, teacher, and soldier became central figures—not as poetic symbols but as everyday protagonists in the building of a new society.

One of the most iconic works of this era was the mosaic frieze on the House of Teachers (Haus des Lehrers), completed in 1964 by Walter Womacka. Spanning over 120 meters, the mural depicts an optimistic vision of socialist life: men and women working together in harmony, studying, teaching, constructing, growing. Its color palette is warm and saturated, its figures monumental but not grandiose. This was not the art of utopia, exactly, but of managed optimism—a future so certain it could be painted in advance.

Painters such as Bernhard Heisig, Werner Tübke, and Wolfgang Mattheuer achieved national recognition by working within, and occasionally bending, the constraints of Socialist Realism. Tübke, for example, smuggled intricate allegories and subtle ambiguities into his vast historical canvases, including the immense Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany mural (1987), painted in Bad Frankenhausen but conceived under the eyes of East Berlin cultural officials. These works navigated a delicate balance between compliance and commentary.

Art schools and guilds reinforced orthodoxy. Admission to the Weißensee Academy of Art or the Dresden Academy, both of which fed into East Berlin’s institutions, required not only talent but ideological trustworthiness. Artists who strayed too far from official themes or embraced abstraction, conceptualism, or Western influences faced marginalization. Exhibitions were state-controlled. Art criticism functioned as reinforcement, not evaluation.

Still, conformity was never complete. In the privacy of studios and homes, artists such as Carsten Nicolai, Cornelia Schleime, and the collective known as Autoperforationsartisten (active in Dresden and Berlin) began creating works that subtly defied the state’s visual language. These early gestures—abstract prints, experimental film, body art—would later find fuller expression as East Germany faltered.

But in the 1950s and ’60s, East Berlin’s public art world remained overwhelmingly uniform: large-scale murals, heroic sculpture, painted affirmations of unity and purpose. Art was public, pedagogical, and grounded in a clearly defined view of the world. What could not be spoken in politics might sometimes be whispered in paint—but only if one was careful.

Capitalist avant-gardes in the West

Across the wall, a different tension gripped West Berlin. The western sectors, administered by the United States, Britain, and France, inherited the wreckage of wartime Berlin along with the challenge of rebuilding a democratic cultural identity under capitalist conditions. Here, freedom of expression became an explicit ideological counterpoint to the East. But freedom, especially in the arts, came with its own set of contradictions.

The West German state promoted artistic pluralism, but with strategic intent. Abstract Expressionism, for example, was supported not only as an aesthetic revolution but as a statement of liberal modernity. Art became a Cold War front: non-figurative painting symbolized freedom, while figuration—especially the kind favored in the East—was cast as regressive.

In West Berlin, this ideology enabled a fertile avant-garde scene. Artists such as Emil Schumacher, Fred Thieler, and Karl Otto Götz explored gesture, material, and spontaneity in ways that stood in sharp contrast to the orderly monumentalism of the East. Galleries like Galerie Springer and Galerie René Block began showing conceptual and Fluxus artists. Joseph Beuys, though more closely associated with Düsseldorf, exhibited in West Berlin and helped reframe the idea of what art could be: performance, process, dialogue.

By the late 1960s, West Berlin had become a magnet for experimental artists, helped by a draft exemption that made it a refuge for young men seeking to avoid military service. The result was an influx of counterculture, student activism, and radical aesthetics. Squatted buildings, repurposed factories, and open-air happenings became part of the artistic landscape.

West Berlin was not free from institutional pressures. Major museums, like the Neue Nationalgalerie (opened in 1968 in a building by Mies van der Rohe), tended to favor canonical modernism—Picasso, Klee, Matisse—over more challenging contemporary work. But alternative spaces flourished: the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program invited dozens of international artists to live and work in the city, including Nam June Paik, Rebecca Horn, and David Hockney.

The art scene in the West was pluralistic, yes—but also fractured. Some artists felt disconnected from the grand narratives of both capitalist and socialist progress. Others engaged directly with West Berlin’s geopolitical isolation, using its liminal status as both symbol and setting. A city with a wall cutting through it could not help but produce artists who questioned the boundaries—physical, political, and conceptual—of perception.

Checkpoint gallery: artists who crossed

Despite the division, there were moments—quiet, rare, and deeply charged—when artists from East and West Berlin crossed paths. The wall was not impermeable. Cultural diplomacy, family visits, and sanctioned exchanges allowed for brief contact. And in these moments, something complex happened: recognition, tension, sometimes influence.

One of the most poignant examples was Käthe Kollwitz’s work, still present in both East and West cultural memory. In 1951, East Berlin inaugurated the Kollwitz Museum, positioning her as a socialist icon. But West Berlin also claimed her legacy, celebrating her as a universal humanist. Her presence in both cities hinted at the shared foundations buried beneath ideological division.

In the 1970s, East German artist Ronald Paris was permitted to visit the Documenta exhibition in Kassel. He returned shaken—not by the art’s formal qualities, but by its conceptual freedom. Others—like AR Penck (born Ralf Winkler)—eventually defected to the West, bringing with them a style that fused GDR visual training with gestural urgency.

Conversely, some West Berlin artists found their ideas echoed or resisted in the East. Joseph Beuys’s notion of social sculpture was closely watched by East German cultural officials, not because they welcomed it, but because they feared its implications. Beuys’s claim that “everyone is an artist” was both democratic and destabilizing—dangerous in a system built on control.

One gallery, symbolic in its name if not its location, was Galerie am Checkpoint Charlie. It hosted exhibitions that explicitly addressed the division of the city. In the early 1980s, it staged shows on border art, smuggling as metaphor, and the aesthetics of surveillance. These weren’t diplomatic exhibitions; they were acts of commentary staged in a city where commentary could still cost you dearly.

Berlin’s art world during the Cold War did not consist of two isolated spheres. It was a pair of mirrors facing each other, distorted and dark, sometimes reflecting, sometimes obscuring. Each side tried to define what art was—and what it was for. Each built institutions, trained artists, and told stories about the past and future. And in each, artists—working within or against the system—found ways to make meaning.

Joseph Beuys in the Shadow of the Wall

Myth, performance, and national healing

By the time Joseph Beuys began exhibiting in West Berlin in the 1960s and 1970s, the wall had transformed the city into both a geopolitical symbol and a psychic wound. Beuys—artist, provocateur, educator, and myth-maker—understood that any art made in Berlin could not be purely visual. It had to be ritualistic. In a divided city haunted by war, genocide, and silence, art needed to function as a healing gesture—even if the wound refused to close.

Beuys’s relationship to Berlin was complex and evolving. Though not a native Berliner, he recognized its centrality to German trauma and transformation. His first significant appearance in the city came in 1977 at the documenta satellite show, but it was in his performances, lectures, and provocations—often staged in or near Berlin—that he most fully inhabited its contradictions.

Beuys’s public persona was inseparable from his private mythology. He often told the story of having been shot down as a Luftwaffe pilot in Crimea during World War II, rescued by nomadic Tatars who covered his body in animal fat and felt—materials he would later incorporate obsessively into his sculpture. The story is mostly unverifiable, possibly fabricated. But that ambiguity was central to his work. Beuys believed that myth could be a vehicle for moral and political transformation, a way to confront the spiritual void left by modern catastrophe.

Nowhere was this more evident than in works like I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), in which Beuys spent three days in a New York gallery with a coyote, wrapped in felt, carrying a shepherd’s staff. Though performed across the Atlantic, the piece spoke directly to postwar Germany: the idea of taming violence through ritual, of meeting history in animal form. In Berlin, such gestures resonated more deeply than they might elsewhere. This was a city of ghosts—of buried ruins and unacknowledged guilt. Beuys’s art didn’t exorcise those ghosts; it invited them in and gave them form.

In 1982, Beuys made his most ambitious public statement at documenta 7 in Kassel, with the piece 7000 Oaks—a long-term environmental sculpture that involved planting seven thousand oak trees, each paired with a basalt stone. Though not staged in Berlin, its implications echoed there: slow, participatory, collective restoration. After Beuys’s death in 1986, artists and curators in Berlin took up the project, extending the planting into Berlin’s own damaged soil. Trees grew in places where buildings had burned, where walls still stood, where silence had once ruled.

In a city of monuments, Beuys offered a counter-monument: living, ambiguous, unfinished.

Teaching as activism: the Düsseldorf connection

Beuys’s greatest influence in Berlin may not have come through his own work, but through the artists he inspired. As a professor at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf—an institution located outside Berlin but deeply connected to its cultural currents—Beuys mentored a generation of artists who would redefine the meaning of German contemporary art. His teaching was radical, not only in content but in form: open classes, egalitarian admission, blurred lines between art, politics, and life.

Among his students were figures who would later shape Berlin’s post-wall art scene, including Katharina Sieverding, known for her monumental self-portraits; Jörg Immendorff, whose politically charged paintings often referenced the division of Germany; and Imi Knoebel, who pursued a minimalist abstraction with metaphysical overtones. These artists carried Beuys’s ideas into their own mediums—not as doctrine, but as provocation.

Beuys insisted that “every human being is an artist,” by which he meant not that everyone should paint, but that everyone had the capacity for creative, world-changing thought. In divided Berlin, this idea took on a particular urgency. Art was not just a profession or a style—it was a means of reimagining the civic body, of refusing both capitalist commodification and socialist prescription.

This attitude extended to Beuys’s political activism. He co-founded the German Green Party, protested nuclear proliferation, and engaged in open debates on education reform, land use, and the failures of postwar reconstruction. In Berlin, his presence blurred the lines between artist, intellectual, and agitator. Even those who rejected his aesthetic admired his audacity.

Beuys’s idea of the “social sculpture”—a society shaped by creative participation—became a touchstone for Berlin’s experimental scene in the 1980s and 1990s. Performance collectives, community art initiatives, and conceptual interventions all drew on his model. His belief in the healing potential of symbolic action remained controversial, but it gave Berlin’s art community a language to address what could not be said outright.

The stag, the felt, and the republic

Beuys’s visual vocabulary—animal fat, felt blankets, copper rods, dead hares—may seem esoteric or cryptic. But in Berlin, these materials resonated with unexpected clarity. Felt could symbolize both insulation and suffocation. Fat, both nourishment and decay. The stag, which appeared in numerous drawings and installations, represented not only nature but sacrifice. These materials carried emotional weight without requiring narrative. In a city that had seen narrative weaponized, this was its own form of freedom.

Perhaps the most telling Berlin performance was How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), a title that carried, for German audiences, the weight of unspoken atrocity. Beuys, his head coated in honey and gold leaf, whispered to a lifeless animal while holding paintings in a dim gallery. The act was absurd, reverent, silent—an attempt to communicate with what could no longer answer. For Berliners, the dead hare could stand in for many things: victims, history, memory itself.

Beuys never offered solutions. His works were not prescriptions but openings. And in Berlin—a city where meaning had been violently imposed for decades—that ambiguity was not a flaw but a gift. His art refused to settle, just as the city refused to forget.

By the time the wall fell in 1989, Beuys had been dead for three years. He did not live to see the reunification of Germany, or the dramatic reshaping of Berlin’s art world that followed. But his influence lived on—in trees, in classrooms, in ideas. In a divided city, he had offered not unity but process. Not monuments, but actions. Not healing, but the possibility of healing.

In postwar Berlin, no artist left a larger philosophical footprint. He did not try to fix the broken republic. He tried to show that it was still possible to make meaning in the wreckage.

Neo-Expressionism and the Pain of Reunification

Baselitz, Kiefer, and the ghosts of the Reich

In the decades following the Second World War, Germany’s cultural landscape remained haunted by absences: of trust, of moral clarity, of names that could no longer be spoken. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the country lurched toward reunification, these wounds—long sublimated—resurfaced with a fresh urgency. In the visual arts, no movement responded more viscerally than Neo-Expressionism, a return to figuration and emotional intensity that sought not to escape history, but to wrestle with it head-on.

Two of its most prominent practitioners—Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer—came to embody the postwar German struggle with identity and memory. Both had deep ties to Berlin. Baselitz was born in Saxony and educated in East Berlin before fleeing to the West in the late 1950s. His early work, filled with grotesque figures and dismembered forms, drew immediate controversy. In 1963, his paintings Die große Nacht im Eimer (“The Big Night Down the Drain”) and Nackter Mann were confiscated for indecency. But it was precisely this willingness to disturb—to dig into the psychic rot beneath the surface—that made his work essential.

In 1969, Baselitz began painting his figures upside down, an act that initially seemed like provocation but became a sustained strategy: to disorient, to disempower the viewer, and to deny narrative certainty. In his Berlin studio, he produced works that echoed with mutilated bodies, fractured national symbols, and a refusal to offer closure. His canvases were not about memory—they were about its failures. He called himself an “anti-humanist,” yet his art remained obsessed with human frailty.

Kiefer, younger and more solemn, operated with a different vocabulary but pursued a similar confrontation. His paintings of scorched landscapes, Nazi architecture, and decaying fields of sunflowers bore titles like Sulamith (invoking Paul Celan’s poem Death Fugue) and Margarethe, linking German guilt with biblical and literary loss. Though based in the Rhineland for much of his career, Kiefer exhibited frequently in Berlin and chose the city for his 1991 installation Bruch und Aufbau (“Rupture and Construction”), a work that used lead, ash, straw, and books to evoke both ruin and rebuilding.

These artists were not interested in healing wounds—they wanted to force their viewers to stare into them. In the euphoric aftermath of the wall’s collapse, their work offered a stark counterpoint: reunification might be political, but reconciliation was not automatic. The ghosts were not gone. They had simply been waiting.

The Berlin Wall as canvas

While artists like Baselitz and Kiefer tackled historical trauma through oil and symbolism, other Berliners turned the wall itself into an immediate, contested medium. Even before its fall, the western face of the Berlin Wall had become one of the most visible and volatile galleries in the world—a 155-kilometer-long, constantly evolving skin of graffiti, stencils, posters, and murals.

In the 1980s, artists such as Thierry Noir, Keith Haring, and Kiddy Citny began painting large, colorful figures on the Wall’s western surface. Noir’s cartoonish heads, often painted at night and in haste, became icons of defiance—not high art, but insistently human. Haring, during a 1986 visit, painted a vivid mural near Checkpoint Charlie: rows of interconnected figures, red on white, symbolizing unity and surveillance. These were not permitted artworks—they were tolerated intrusions, reminders that the Wall could not fully control the visual space around it.

After the Wall fell in 1989, its surface became an even more charged site. In 1990, 118 artists from 21 countries were invited to paint 1.3 kilometers of the Wall’s eastern face, now designated the East Side Gallery. Their works ranged from hopeful to mournful to biting: Dmitri Vrubel’s famous My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love—a reproduction of the fraternal kiss between Brezhnev and Honecker—became a global symbol of Cold War absurdity. Elsewhere, fragments of the Wall were chipped off, sold, or scattered around the globe.

The Wall, once a symbol of imprisonment, was now a canvas of memory and contestation. But it also raised questions: Who owned this history? Could painting the Wall defang it? Was it being commemorated or commodified?

Some Berliners argued that the East Side Gallery sentimentalized suffering or offered a sanitized version of division. Others defended it as a necessary record—a space where former boundaries could be re-inscribed as dialogue. The debates around the Wall’s remains reflected broader tensions in reunified Berlin: between remembering and moving on, between mourning and marketing, between authenticity and spectacle.

Grief, irony, and the new figuration

Reunification brought together not only two German states, but two artistic legacies. East German artists, long excluded from international networks, found themselves suddenly visible—but often misunderstood or marginalized. Many West German critics viewed their work as provincial or compromised by decades of state oversight. In response, a number of East Berlin artists embraced new figuration—a style that allowed for irony, autobiography, and unresolved emotion.

Painters like Cornelia Schleime, Angela Hampel, and Doris Ziegler, who had once worked under censorship, now explored themes of gender, memory, and transformation. Schleime, in particular, used photography and performance to confront her surveillance by the Stasi, reclaiming her own image as a site of control and resistance. Her portraits—muted, sensual, defiant—stood in quiet opposition to the monumentalism of both East and West.

Berlin also witnessed the rise of Neue Leipziger Schule, a loosely affiliated group of figurative painters who trained in Leipzig but found their public in Berlin. Most famous among them was Neo Rauch, whose dreamlike canvases merged Socialist Realist architecture with surreal disjunctions. His figures wandered through factories, fields, and offices, trapped in histories that made no linear sense. Rauch’s work was deeply German, deeply East, but also cryptically universal.

For many of these artists, grief and irony were not opposites, but modes of survival. The abrupt collapse of East German institutions created not just opportunities, but identity crises. What did it mean to be an East German artist in a country that no longer recognized “East Germany” as valid? What did it mean to be a Berlin artist in a city that was both ancient and newborn?

Throughout the 1990s, Berlin’s art scene became a site of both flourishing and fragmentation. New galleries opened in Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg. International curators flooded in. But beneath the buzz, deeper tensions remained. The promise of reunification had not erased the past—it had only changed its vocabulary.

And in this shifting city, where history seemed to flicker like a slide projector between eras, Neo-Expressionism remained a vital language. It spoke not of triumph, but of continuity in pain—of images too urgent to suppress, too complex to resolve.

Berlin as Bohemia: 1990s Countercultures

Squats, ruins, and the romance of the East

In the aftermath of reunification, Berlin became Europe’s most unlikely artistic frontier—a sprawling, semi-ruined capital where the rules were suspended and the future uncertain. The early 1990s were not glamorous. Entire districts of the former East—Prenzlauer Berg, Friedrichshain, Mitte—were hollowed out, their buildings abandoned or half-occupied. Infrastructure was failing. Bureaucracies collided. Rents were negligible. And amid the institutional chaos, a generation of artists, musicians, and dreamers rushed in to build something new from the wreckage.

Many came from West Germany or Western Europe. Others were former East Berliners, now unmoored from state institutions but hungry for self-expression. What united them was not a program or movement but an attitude: improvisation over permanence, autonomy over professionalism, raw space over clean white walls.

Squatting was not just a housing solution; it was a political and aesthetic act. Empty factories became galleries. Derelict apartment buildings hosted impromptu exhibitions, noise concerts, and film screenings. The former death strip that had run along the Berlin Wall—once patrolled and mined—became fertile ground for performance art, sculpture parks, and illegal clubs. Artists moved into spaces with no heating, no plumbing, no permits. They hauled in salvaged materials, rigged makeshift lights, and turned concrete husks into temporary utopias.

These spaces were not only abundant—they were symbolic. To paint on a wall in Friedrichshain was to declare that the state no longer defined space. To stage a performance in a squat in Mitte was to announce that culture no longer needed institutions. Everything was contingent. Everything was shared. Art happened in stairwells, attics, bunkers, and courtyards.

This was not a rejection of art history so much as a rejection of its gatekeepers. Young Berlin artists didn’t care about institutional legibility. They wanted intensity. They wanted risk. And the city—bombed, divided, and suddenly leaderless—gave it to them.

The myth of 1990s Berlin as a bohemian paradise has since been commercialized and softened. But the truth was messier, and more generative. This was a time of:

- Collaboration over authorship: Artists formed collectives like Kunsthaus Tacheles, housed in a partially bombed-out department store, where hundreds of creators lived and worked without centralized governance.

- Ephemerality over permanence: Installations were often destroyed within days by weather, police, or rival artists. The work was made to vanish.

- Physicality over theory: Berlin’s early post-wall art often emphasized materiality—concrete, metal, fabric, waste—rejected by earlier conceptual norms.

This freedom was temporary. But while it lasted, Berlin was not just a city with art. It was a city that was art.

Techno, trash, and transgression

At the heart of Berlin’s 1990s artistic explosion was a pulsing, non-stop beat: techno. The sound of reunified Berlin was not orchestral, not jazz, not rock. It was industrial, relentless, borderless. And it was more than a soundtrack—it was a medium.

Abandoned power plants, hangars, bunkers, and factories were transformed into clubs, and the line between club and art space quickly blurred. Tresor, founded in 1991 in a former bank vault beneath Leipziger Straße, became a nexus of music, light, performance, and architecture. E-Werk, housed in a decommissioned power station, staged massive nights where DJ sets were accompanied by experimental visuals and site-specific installations.

These weren’t just hedonistic playgrounds. They were laboratories for new forms of expression. Many artists moonlighted as DJs, VJs, or light designers. Club flyers became graphic design artifacts. Costumes and staging borrowed from Dada, performance art, and post-apocalyptic cinema. Berlin techno culture, in its earliest years, was deliberately anti-commercial, intensely queer, and defiantly self-invented.

Trash aesthetics flourished. Artists scavenged materials from abandoned Soviet buildings, East German office blocks, and construction sites. Installations featured broken monitors, doll heads, barbed wire. The visual language was raw, ironic, and sometimes deliberately offensive. It drew from punk, but also from the blunt realism of East German design. Everything was reused, broken down, reassembled. Berlin’s artists didn’t make statements—they made ruins speak.

The borders between subcultures dissolved. Painters collaborated with hackers. Sculptors built sound systems. Performances happened at four in the morning, during club nights, with no documentation. Art school was optional. Street cred was not.

This was a decade when Berlin felt like a capital without a state—and art filled the void. It didn’t offer solutions. It offered energy. Transgression, not harmony, was the guiding value. And yet, within the wreckage, something lasting was being built.

The art of temporary utopias

If the early 1990s offered Berlin a kind of anarchic freedom, by the decade’s end the first signs of normalization were creeping in. Real estate developers arrived. Cultural administrators took note. Museums and biennials began courting the same artists who had once defied them. Some spaces were legalized. Others were evicted. The city’s image, once chaotic and unreadable, began to be branded.

But the spirit of the 1990s left a deeper imprint than any marketing campaign. Artists who came of age in this period carried its principles into new forms: socially engaged art, participatory installations, nomadic curatorial platforms. Even as Berlin professionalized, it retained a sense of the ephemeral as valuable—that something need not last to matter, that impermanence could itself be a medium.

Some of these temporary utopias became institutions. Kunst-Werke Berlin, founded in a former margarine factory in Mitte, evolved into the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, host of the Berlin Biennale. Berghain, a techno club born from the remains of Ostgut, became an unlikely venue for art installations and commissions. Sophiensaele, once a squat-friendly performance space, became one of Berlin’s premier venues for experimental theater and performance art.

And yet, the feeling persisted that the best things were happening elsewhere—in basements, in former offices, in spaces not yet claimed.

The art of 1990s Berlin was not about creating masterpieces. It was about building communities, testing boundaries, and inhabiting a city as a question, not an answer. It was a time of false starts, abrupt endings, fierce debates, and unrepeatable nights. It taught a generation that art could be life—messy, difficult, collective, and, above all, possible.

The Biennale Era and Globalization’s Grip

When curators took the throne

By the turn of the millennium, Berlin’s art scene had transformed from a scrappy, squat-driven improvisation into a central node in the global art market. No longer a city on the periphery, Berlin became a destination—not just for artists seeking cheap rent and open space, but for collectors, curators, and cultural bureaucrats. And with this influx came a shift in power: the curator, not the artist, became the architect of meaning.

This change crystallized with the launch of the Berlin Biennale in 1998, an event designed to position the city alongside Venice, São Paulo, and Documenta as a hub of international contemporary art. The first edition, held in the dilapidated Kunst-Werke complex in Mitte, captured the spirit of the 1990s: raw, participatory, critical. But as the Biennale gained prestige, its tone and scale shifted. Subsequent editions drew on an increasingly global roster of artists, often shaped around tightly curated themes: migration, post-colonial memory, institutional critique.

Curators such as Klaus Biesenbach, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Cathrin Pichler took on roles once reserved for artists. They wrote manifestos, assembled transnational teams, and approached exhibitions as intellectual interventions rather than local celebrations. The art object became less important than the curatorial concept. Biennales no longer displayed what was “new” in Berlin—they explained what Berlin meant.

This approach had its strengths. It brought urgent political and theoretical debates into the public sphere. It highlighted artists from outside Europe and the United States, challenging the dominance of Western modernism. It transformed forgotten spaces—an old Jewish girls’ school, a crumbling warehouse, an abandoned train depot—into temporary stages for ambitious ideas.

But it also introduced a new kind of alienation. Many Berlin-based artists, particularly those rooted in the local scene, found themselves excluded from the very exhibitions held in their city. The language of the biennial—dense, theoretical, often global in scope—felt increasingly disconnected from the material and emotional texture of Berlin itself. The city was being framed for export, not for its inhabitants.

The rise of the Biennale reflected a broader truth: Berlin had become an art capital, but at the cost of its intimacy. Curators were shaping its image. Artists were adapting to its machinery.

Institutional critique as self-parody

Alongside this ascent of curatorial culture came the rise—and eventual weariness—of institutional critique. Building on the conceptual strategies of the 1960s and ’70s, artists in Berlin and beyond began making work that analyzed, exposed, or satirized the very institutions that displayed it: galleries, museums, funding bodies, residency programs. The artist was no longer outside the system; they were inside it, taking it apart from within.

Berlin, with its patchwork of public institutions and alternative spaces, became a natural laboratory for this approach. Artists like Olaf Nicolai, Hito Steyerl, and Tino Sehgal produced works that directly questioned the production, circulation, and consumption of art. Steyerl’s video essays, including How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013), interrogated surveillance, visibility, and the politics of representation. Sehgal, by contrast, eliminated the physical art object altogether, choreographing “constructed situations” in which performers engaged viewers in conversation, song, or movement.

These works were often brilliant. But as the years passed, a creeping irony set in: the critique became the brand. Museums and biennials embraced institutional critique as a genre, programming it alongside retrospectives and design shows. The very works meant to destabilize the system became tools of its renewal.

For Berliners, this dynamic could feel suffocating. The same city that once fostered anti-establishment energy was now professionalized to the point of performance. Artists spent more time writing grant applications than making work. Political gestures risked becoming mere theater, staged for curators and art fair audiences. The space for risk and failure narrowed. The stakes grew smaller, even as the budgets grew larger.

Yet even amid this self-parody, moments of clarity broke through. The 9th Berlin Biennale (2016), curated by the New York collective DIS, was widely criticized for its slickness and superficiality. But it also forced a reckoning with the commodification of critique itself, the way radical aesthetics had become marketing strategies. Its excesses were not glitches—they were revelations.

Art fairs, funding, and friction

By the 2010s, Berlin’s place in the international art world was secure. Major galleries like Sprüth Magers, Galerie Eigen + Art, and Klemm’s anchored the commercial scene. The city hosted a growing constellation of art fairs, including Art Berlin Contemporary (ABC) and Positions Berlin, both of which attempted to blend the scale of global commerce with the city’s more experimental tendencies.

But the relationship between the market and the scene was uneasy. Many artists who had come to Berlin for its freedom now found themselves priced out of their studios. Rents rose. Developers moved in. Spaces like Tacheles, once symbols of anarchic creativity, were closed, redeveloped, or sanitized. The galleries that replaced them were often sleek, international, and disconnected from the communities they displaced.

Public funding, a lifeline for Berlin’s independent artists, became increasingly competitive and bureaucratized. Applications required fluency not only in art but in policy language. Success meant navigating a landscape shaped as much by cultural diplomacy as by aesthetics.

This friction produced new forms of resistance. Project spaces like Spor Klübü, Kinderhook & Caracas, and After the Butcher began operating with minimal resources, hosting exhibitions, discussions, and screenings without market pressure. They rejected the visibility of the art fair in favor of local specificity and informal networks. Some artists turned toward pedagogical models—working in schools, neighborhood centers, or activist collectives. Others left the city entirely, frustrated by its transformation.

By the end of the decade, a paradox had taken hold: Berlin remained one of the most affordable art capitals in the West—and yet, it no longer felt free. The weight of international attention, the professionalization of once-informal networks, the pressure to perform politics—all of it shaped a new kind of constraint.

And still, the city produced extraordinary work. It remained porous, unstable, open to reinvention. The biennial era had not killed Berlin’s soul. But it had changed the terms of engagement. Artists now operated with full awareness of their visibility—and the costs that came with it.

Post-Studio Berlin: Where Artists Live, Not Just Exhibit

Uferhallen, KINDL, and the factory aesthetic

By the early 2020s, Berlin’s art scene had entered a new phase—no longer defined by rebellion, nor fully absorbed by institutional spectacle. What emerged was a post-studio condition, where the boundary between life, labor, and artistic practice grew increasingly porous. In a city shaped by improvisation and vacancy, artists were no longer simply showing in Berlin. They were living within their work—often literally, in vast converted factories, industrial hangars, or collective ateliers that functioned as homes, studios, and public platforms all at once.

Among the most emblematic of these hybrid sites is Uferhallen, a former tram depot in Wedding that has become a dense ecosystem of studios, rehearsal spaces, and project rooms. Artists here don’t merely rent square meters—they inhabit the infrastructure, shaping it into a social and aesthetic environment. Uferhallen hosts exhibitions, concerts, screenings, and debates, but it’s the dailiness of the place—its clanking pipes, its communal kitchens, its proximity to production—that gives it meaning. Art happens slowly, collectively, and sometimes incidentally.

The visual aesthetic of these spaces is not incidental. Berlin’s post-studio environments are almost always industrial, not by design but by historical accident. The post-war division and economic stagnation left vast swaths of the city underused. As artists reclaimed them, a style emerged: unpainted concrete, exposed brick, remnants of machinery, repurposed tools. Rather than erase the past, these spaces preserve it, and in doing so, position art within a broader historical metabolism.

KINDL – Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst, housed in a former brewery in Neukölln, exemplifies this approach. Its large-scale exhibitions often respond to the building’s industrial past: artists create installations that resonate with the vastness of the brewing tanks, the brick vaults, the echoing stairwells. KINDL does not separate art from architecture—it invites contamination. Visitors are asked not only to look, but to dwell, to linger, to consider where they are.

This return to materiality—space, architecture, labor—is not a retreat from the conceptual. Rather, it reflects a broader shift in Berlin’s art world: away from the discursive and toward the embedded. Artists are no longer interested in explaining Berlin. They want to make work that exists within it, as part of its economic, spatial, and social conditions.

And in a city increasingly defined by precariousness, that act of inhabitation becomes a form of resistance.

Artists as landlords, landlords as curators

Yet this new entanglement of space and practice has created new tensions—especially as real estate becomes both a threat and a tool. The old model of the independent, under-the-radar artist studio has begun to collapse under market pressure. Instead, a new class of artist-landlords and landlord-curators has emerged, reshaping the city’s creative geography.

Some artists, benefiting from early investments or family wealth, have purchased studio spaces outright and transformed them into semi-commercial ventures. These aren’t traditional galleries, but artist-run buildings, where studio rentals fund exhibitions, and exhibitions justify zoning exemptions. The economic model is cooperative, but the stakes are high. In neighborhoods like Moabit and Lichtenberg, these complexes now function as micro-institutions, complete with residency programs, public programming, and international visibility.

Meanwhile, developers have caught on to the cultural capital of art. In the 2010s, it became common for new construction projects to include pop-up exhibitions, artist commissions, or short-term studio offers as part of their marketing strategy. These aren’t cynical add-ons—they’re central to the gentrification playbook, using artistic presence to inflate neighborhood value. In Berlin, art has become a tool of urban speculation, even as artists are among its first victims.

The relationship between artist and landlord is no longer adversarial. In some cases, they are the same. In others, they collaborate. A new kind of professional has emerged: the cultural developer—someone who speaks both the language of art and of zoning law, who knows how to balance noise complaints with grant applications.

This has led to a subtle but profound change in how Berliners think about art: not as objects, but as infrastructures. A project is not a painting—it’s a building. An exhibition is not an event—it’s a lease term. An artwork is not complete until it’s shown, documented, circulated, and written into a proposal for municipal funding.

In this environment, artists face a paradox: they must claim space to survive, but every claim they make helps fuel the mechanisms that threaten their survival. There is no outside to the system—only degrees of agency within it.

The uneasy triumph of creative capital

By the mid-2020s, Berlin had become a cautionary tale and a success story at once. It remained one of the most vital centers for contemporary art in Europe, with hundreds of project spaces, dozens of major galleries, and a dense network of residencies and festivals. But it also had one of the fastest-rising real estate markets in the EU. The very conditions that once made the city fertile for experimentation—cheap space, institutional neglect, historical instability—had largely vanished.

And yet, artists stayed. They adapted. They organized. Collective ownership models gained traction, with initiatives like ExRotaprint in Wedding and ZUsammenKUNFT near Potsdamer Platz showing how artists and activists could co-develop buildings outside of speculation. These were not romantic squats—they were legal, professional, cooperative. The bohemian myth of the 1990s was replaced by a post-capitalist pragmatism, equally wary of the market and the state.

Still, creative capital had won. Berlin’s image as a city of artists was no longer marginal—it was municipal policy. Tourist campaigns touted its galleries. Startups used studio aesthetics to sell software. The Berlin Senate Department for Culture allocated millions in funding each year, often with rigorous accountability requirements that made spontaneity difficult.

And yet, art kept happening. Not just in big institutions, but in the cracks: an impromptu reading under S-Bahn tracks, a sound installation in a stairwell, a film screening projected onto a construction tarp. Berlin had become too expensive to be careless—but it was still too haunted to be complacent.

The city, in the end, was not a canvas. It was a medium. And the artists who stayed understood that working in Berlin meant working with its ghosts, its scaffolding, its contradictions. Not despite them. But through them.