The first Armenian artworks were carved not in canvas or parchment, but in volcanic rock under open skies. High on the windswept plateaus of the Armenian Highlands, some of humanity’s earliest artistic gestures endure—not in museums, but etched into the dark stone of ancient mountains. These prehistoric petroglyphs, dense with abstraction and mystery, offer a visual language that predates writing and yet gestures toward a symbolic consciousness both startlingly sophisticated and intensely local.

Petroglyphs of Ughtasar and Gegham Mountains

Over 20,000 petroglyphs have been cataloged in Armenia’s high-altitude regions, most notably at Ughtasar near Sisian and along the Gegham Mountains. Dating from the 5th to the 1st millennium BC, these rock carvings document a prehistoric visual imagination concerned less with naturalistic depiction than with conceptual and cosmological ordering. At Ughtasar, circular motifs abound—sun discs, wheel-like forms, and labyrinthine spirals—interspersed with schematic representations of animals, hunters, ritual dances, and processions. Carved into andesite stones, many of these images appear at elevations above 3,000 meters, suggesting their function was not merely decorative but spiritual or calendrical.

The Gegham petroglyphs show a similarly rich symbolic vocabulary. A recurring figure—part animal, part human, often horned or radiating—invites speculation about shamanic rites or mythic storytelling. Scholars have posited that these carvings reflect a proto-religious cosmology: an effort to inscribe the rhythms of hunting, fertility, and celestial cycles into stone. Some motifs, especially the radiating sun figures, suggest early solar worship, a tradition that would echo through Armenian Zoroastrianism and survive even into Christian iconography.

Three visual patterns recur with notable frequency and sophistication:

- Interlinked spiral forms, often arranged in threes, possibly signifying birth, death, and regeneration.

- Stylized stags and ibexes with exaggerated antlers, standing as both prey and sacred symbols.

- Human figures in contorted or elevated postures, sometimes with upraised arms, suggesting invocation or trance.

These carvings, though prehistoric, are not primitive. They evidence a conceptual clarity that resists the flattening gaze of modern ethnographic generalization. Rather than imitating the visible world, the petroglyphs construct an intelligible, even abstract system of symbols—a nascent visual culture rooted in metaphysics as much as material survival.

Shamanic Symbols and Proto-Script

Among the most tantalizing aspects of Armenian prehistoric art is the apparent presence of proto-writing: glyphs and marks that hint at a system of recorded meaning without becoming fully alphabetic. At Ughtasar, rows of signs resembling early cuneiform or pictographic notation have prompted theories of an indigenous ideographic system. Some researchers, drawing parallels with Hittite hieroglyphs or proto-Elamite scripts, suggest these marks may represent clan names, sacred numbers, or astrological information.

Equally compelling is the shamanic dimension of these early carvings. The altitude, isolation, and consistent themes of transformation suggest a ritual function. The human-animal hybrids, the trance-like body postures, and the proximity to water sources all echo patterns found in shamanic traditions across Central Asia and Siberia. This places Armenian prehistoric art not in a vacuum, but within a broader cultural continuum of mountain-dwelling, spirit-invoking societies. Yet the Armenian variant remains distinctive for its density, endurance, and continued cultural relevance.

In oral traditions from regions near Syunik and Vayots Dzor, tales of “stone spirits” and “ancestor marks” persist—vestigial memories, perhaps, of a once-integrated worldview in which carving the stone was not merely artistic but metaphysical action.

Ritual Objects and Megalithic Structures

Beyond the petroglyphs, Armenia’s early Bronze Age material culture includes a striking array of carved ritual objects—obsidian amulets, animal figurines, and phallic stones—alongside megalithic monuments such as Zorats Karer, often called the “Armenian Stonehenge.” Situated near Sisian, this complex of over 200 upright stones—some pierced with circular holes—dates from around 2000 BC, though some scholars argue for significantly earlier origins. Whether calendrical observatory, necropolis, or ceremonial site, Zorats Karer speaks to an integrated architectural-artistic impulse: a world in which stone was both medium and message.

Among the more intimate artifacts are polished basalt idol-stones, often with incised eyes or breasts, suggesting a cult of fertility or ancestor veneration. These objects are rare but revealing: small-scale works that condense symbolic force into palm-sized forms. Their simplicity belies a complex conceptual apparatus—one in which the human body becomes a proxy for cosmic forces.

A particularly vivid scene emerges from the burial mounds (kurgans) excavated near Artik and Metsamor. Here, archaeologists have uncovered ceramics adorned with tightly spaced geometric motifs—zigzags, swirls, and ladder-like forms—alongside bronze figurines of bulls and stylized birds. These artifacts suggest not only aesthetic sophistication but a layered ritual economy, in which form, function, and belief were inseparable.

The artistic language of prehistoric Armenia was one of endurance: not only in the literal sense of stonework surviving millennia, but in the conceptual sense of ideas, symbols, and gestures passing through time in altered but recognizable form. Even as Christianity transformed the region’s religious landscape, the emphasis on sacred mountains, carved stone, and abstract symbolism remained strikingly intact.

The legacy of Armenia’s earliest art is not merely archaeological. It is visible in the enduring reverence for stone, the national attachment to highland landscapes, and the symbolic condensation that characterizes Armenian sacred art across centuries. These ancient carvings did not vanish—they whispered forward.

Urartu and the Roots of Armenian Aesthetic

When the kingdom of Urartu emerged in the 9th century BC around Lake Van, it did more than consolidate military power—it inaugurated a material and visual culture that would cast a long shadow over the Armenian plateau. Urartu, the Iron Age civilization that flourished across what is now eastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, and modern-day Armenia, forged a distinct aesthetic at the crossroads of empire and terrain. Though the Urartians left no continuous literary legacy, their visual culture—etched in bronze, carved into fortress walls, and cast in monumental sculpture—gave shape to one of the foundational layers of Armenian art.

Royal Iconography and Fortress Art

The Urartian elite communicated their authority not with soft grandeur but with precision and control. Inscriptions from kings such as Argishti I and Sarduri II often accompany reliefs of lion hunts, winged deities, and enthroned rulers. These motifs—rendered in low relief on basalt walls and commemorative stelae—projected not emotional charisma but divine endorsement and administrative order. They were part of a state machinery that fused theology and bureaucracy with visual clarity.

The great fortress of Erebuni, founded in 782 BC by Argishti I, offers a particularly rich example. Its walls were once brightly painted in mineral pigments—reds, blues, and ochres—now faded, but detectable in fragments. Frescoes depict stylized trees, processions of dignitaries, and geometric patterning echoing earlier Bronze Age motifs. At once ceremonial and militarized, these images helped assert control over conquered peoples and unify disparate regions under a singular ideological vision.

Three recurring visual strategies define Urartian royal art:

- Rigorous symmetry, used to signify divine or royal order.

- Stylized animal iconography, especially bulls and lions, functioning as apotropaic emblems.

- Bilingual inscriptions (Urartian and Assyrian), blending visual with textual authority.

Though influenced by neighboring Assyria, Urartian visual culture diverged in tone. Where Assyrian reliefs exulted in gore and motion, Urartian scenes tend toward stillness and abstraction, emphasizing containment rather than spectacle. This restraint would echo through Armenian art, in which sacred geometry and ordered space often supersede narrative intensity.

Ornament, Utility, and Power

Urartian artistry extended beyond fortress walls into the realm of everyday and ritual objects. Their metalwork—particularly in bronze—demonstrates a dual commitment to functionality and aesthetic intricacy. Ritual cauldrons, often decorated with cast figurines of bulls or winged deities around the rim, were more than vessels; they were theological declarations rendered in utilitarian form. These objects were frequently discovered in temple precincts or burial sites, underscoring their role in both civic and spiritual life.

Urartu’s metallurgists excelled in lost-wax casting, producing weapons, jewelry, and ceremonial artifacts that balance elegance with martial rigor. Swords inscribed with royal dedications, bronze belts embossed with narrative scenes, and finely chased pectorals reflect a society where art was inseparable from power. These items were not merely owned—they were worn, wielded, and displayed in a performance of authority.

One of the most striking examples is a series of bronze shields excavated near Lake Sevan, decorated with concentric rings of stylized animals. These not only defended bodies but also reinforced a cosmic order—the circles of imagery mirroring the cycles of time and rule.

This synthesis of ornament and purpose is crucial in understanding Armenian aesthetics. Later Armenian liturgical objects, from chalices to cross reliquaries, preserve the Urartian instinct: beauty not as luxury, but as embedded meaning in form.

Continuities with Hittite and Assyrian Forms

Urartian art was never created in isolation. It developed in dialogue with, and in resistance to, larger imperial systems—chiefly the Hittite and Assyrian empires. The Hittite influence is evident in the use of monumental gates flanked by guardian figures, while Assyrian inspiration is seen in the hierarchical scale of figures and narrative sequences in relief sculpture. But Urartu absorbed these styles only to remake them.

Where Assyria’s visual language was expansive and imperialist, Urartu’s was introspective and bounded. Its mountain temples and walled citadels suggest a worldview more defensive than messianic, concerned with ritual repetition over conquest mythology. This tendency toward inward refinement—toward making visual meaning through restraint and harmony rather than domination—would find later expression in Armenian ecclesiastical art.

The story of the Urartians ends abruptly in the 6th century BC, when the kingdom fell to the Medes and later absorbed into the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Yet their visual language persisted. Many Armenian place names preserve Urartian roots. Architectural techniques—including stone plinths, cyclopean masonry, and centralized sanctuaries—resurface in medieval Armenian monasteries. Even the emphasis on high-altitude sanctuaries and mountain fortresses finds resonance in Armenia’s ecclesial topography.

The Urartian legacy in Armenian art is not merely archaeological—it is conceptual. It embedded a vision of art as integrative: tying administration to cosmology, defense to ritual, and ornament to ontology. The precision of their line, the gravity of their composition, and their mastery of bronze and basalt offered Armenia an artistic inheritance not only of forms, but of attitudes. The ethos of balance and clarity established by Urartu would remain a subterranean current in Armenian visual thinking, resurfacing—often unacknowledged—in the forms of crosses, domes, and manuscripts centuries later.

The Conversion of a Kingdom: Early Christian Art in Armenia

In AD 301, Armenia became the first kingdom to adopt Christianity as a state religion—an act as much political as spiritual, but one that forever changed the visual culture of the region. This conversion did not simply replace pagan symbols with Christian ones; it restructured the entire grammar of Armenian art. Sacred architecture, liturgical objects, and iconographic programs were born almost overnight, yet built on deep substrata of indigenous and classical forms. What emerged was a uniquely Armenian Christian aesthetic: austere, intellectual, and spatially transcendent.

The Invention of the Armenian Church Architecture

The early Armenian church did not evolve slowly—it leapt into existence with startling originality. The first canonical churches, such as the 4th-century cathedral of Etchmiadzin (originally built by Gregory the Illuminator and King Tiridates III), were architectural statements of theological revolution. These were not derivative structures borrowing from Roman basilicas or Eastern Syrian models. Instead, Armenian architects developed a centrally planned, domed cruciform style that would become a signature of the national church.

Etchmiadzin’s plan—square at the base, with apses projecting outward and a central dome rising on a drum—embodied theological and cosmological meanings. The centralized dome was not merely structural; it marked the intersection of heaven and earth, an axis mundi rendered in volcanic tuff. As Armenian architecture matured, so did its symbolic ambition. Later variations, such as the Hripsime and Gayane churches (7th century), refined the tetraconch plan, embedding sacred geometry into every stone joint.

This early architectural genius was marked by:

- Rhythmic massing of volumes, achieving equilibrium without ornament.

- Thick, inward-curving walls that conveyed solidity and inwardness.

- Integration of light through small, strategically placed windows, emphasizing the mystery of divine illumination.

These structures were not built to impress imperial patrons or rival cathedrals abroad. They were conceived as theological machines—spatial embodiments of monastic and liturgical thought. Their abstraction would influence both Byzantine and Georgian church architecture, but in Armenia it remained grounded in a native sense of stone and scale.

Iconoclasm and Visual Restraint

Unlike their Byzantine contemporaries, early Armenian Christians did not develop a robust program of wall painting or figural mosaics. Whether due to theological caution, resource constraints, or native aesthetic preferences, Armenian ecclesiastical interiors emphasized space, form, and sacred geometry over figuration. This restraint was not the product of external iconoclasm (though Armenia would later engage in debates over images) but an internal logic that privileged logos over image, form over illusion.

What imagery did appear tended to be highly selective and symbolic. Stone carvings on tympanums or capitals might show crosses, stylized vines, or animals with theological associations—lions, eagles, or doves. But these were rarely narrative in nature. Even when figural reliefs were introduced, such as on the exterior of the 7th-century Zvartnots Cathedral, they were subordinate to architectural rhythm rather than illustrative tableau.

The preference for abstraction and reduction can be seen as an extension of earlier Urartian sensibilities. Just as Urartian art distilled power into geometry and symmetry, so too did Armenian Christian art reject the seductions of illusionism in favor of conceptual rigor. The sacred was not made visible by rendering it human; it was invoked by structuring space in its image.

This aesthetic restraint was not static. As the centuries progressed, Armenian monasteries such as Geghard and Odzun began to incorporate more figural carvings—bishops, angels, Christ—but even these maintained a hieratic, schematic quality. Unlike Byzantine icons, which glowed with gold and emotional intimacy, Armenian representations remained sculptural and distant, designed more for contemplation than affect.

The Role of Saint Gregory the Illuminator in Shaping Sacred Art

At the center of Armenia’s early Christian transformation stands the figure of Saint Gregory the Illuminator—not just as a proselytizer, but as a shaper of artistic vision. His biography, semi-mythical and politically crafted, was itself a kind of visual narrative, retold through stone reliefs, liturgical manuscripts, and cathedral dedications. Gregory’s legendary imprisonment in the Khor Virap pit, his visions of Christ striking the earth to reveal the site of Etchmiadzin, and his anointing of the royal family provided Armenia with its own sacred mythos, visually encoded into its earliest churches.

The connection between Gregory’s spiritual authority and architectural space was not incidental. The very name Etchmiadzin—”the descent of the Only-Begotten”—frames the church as both historical site and metaphysical event. In commissioning the church at the place of his vision, Gregory linked vision, site, and construction in a single act: the art of sacred architecture became a literal manifestation of revelation.

This fusion of divine event and physical structure is visible in the earliest Armenian reliefs. The cross—often plain, sometimes flanked by peacocks or grapevines—became the principal visual symbol, not the crucified Christ. The absence of suffering imagery, even in passion scenes, reveals an Armenian theology focused more on resurrection than on torment, on transcendence rather than pathos.

Gregory’s role also shaped the Armenian Church’s deep alignment with monasticism. From the outset, Armenian sacred art emerged in tandem with ascetic practice. Monasteries were not just centers of prayer—they were ateliers of architectural, liturgical, and scriptural innovation. This monastic culture, seeded by Gregory and his followers, gave Armenian art its cerebral quality: visuality as the servant of meditation, not emotion.

By the end of the 5th century, Armenian Christian art had defined its core vocabulary: centralized stone churches, minimalist interiors, symbolic reliefs, and a theological orientation toward abstraction and cosmological order. Unlike neighboring Byzantium, which grew increasingly enamored of lavish mosaics and imperial spectacle, Armenia forged a Christian aesthetic of gravity, austerity, and intellectual integrity. It would remain one of the most distinctive—and enduring—visual cultures of the Christian world.

Carved in Stone: Khachkars and the Art of Devotion

Nowhere is the singular spirit of Armenian Christian art more vividly realized than in the khachkar—a carved stone cross often standing alone, unadorned by narrative context, yet vibrating with symbolic density. These objects, which began to proliferate in the 9th century and continued evolving for nearly a millennium, are among the most distinctive contributions of Armenia to the global history of religious art. More than tombstones or votive markers, khachkars are devotional architectures in miniature—compressing theology, memory, and geometry into a single upright slab.

Origins and Evolution of the Khachkar Form

The term khachkar—literally “cross-stone”—describes a form whose surface and composition gradually refined across centuries. Early examples were simple: a plain cross carved into a rectangular block, sometimes with a floral or interlaced motif at its base. But by the 12th century, the khachkar had become a canvas for near-baroque intricacy. Lattices, sunbursts, rosettes, pomegranates, scrolls of foliage, and abstract knots would radiate outward from the central cross in layers of meaning and detail.

The form evolved not merely in complexity but in symbolic scope. Khachkars marked graves, yes, but they were also raised to commemorate victories, endowments, or acts of penance. Monasteries such as Noratus, Goshavank, and Haghpat became forested with them—each one singular, each a personal and communal act of devotion. While a Western Gothic cathedral might take decades to build, a khachkar could be carved by a master in weeks, yet embody theological truths just as complex.

By the 13th century, certain master carvers became known by name: Poghos, Momik, and others who signed their works as artists in their own right. This emergence of artistic identity within a sacred form reveals not the secularization of the khachkar, but its intensification as a vehicle of spiritual self-expression.

Across regions and eras, khachkars maintained three formal constants:

- A central cross, often rooted in a stylized tree of life or stepped pedestal.

- A field of ornament radiating outward in fractal-like layers.

- A surrounding band or frieze, sometimes inscribed with prayers or dedications.

Yet no two khachkars are identical. Their differences—of line weight, depth, density, and iconographic arrangement—bear witness to a tradition that encouraged variation within ritualized form, echoing Armenian liturgical chant with its interplay of fixed structure and improvisation.

Regional Variations and Iconographic Codes

Khachkars differ subtly between regions—variations that reflect not only artistic schools but theological emphases and local cosmologies. In Syunik, khachkars are often tall and narrow, with emphasis on verticality and minimal side decoration. In contrast, those of Lori and Tavush tend toward broader proportions, with luxuriant floral carvings spilling into the borders. At Noratus, near Lake Sevan, over 800 khachkars stand in various states of weathering, forming a sculptural archive of nearly 1,000 years of stone theology.

The iconography, too, varies. Some khachkars incorporate miniature figures—saints, donors, angels—usually placed at the base or flanking the cross. Others include solar discs behind the cross, integrating pre-Christian motifs of the sun with Christian ideas of divine radiance. Still others merge cross and tree, suggesting not only crucifixion but blossoming: a theology of life emerging from death, matter transfigured into spirit.

Three especially unusual iconographic types are worth noting:

- The “wheel-cross,” where the arms of the cross become spokes, possibly echoing Zoroastrian or solar symbolism.

- The “openwork khachkar,” where negative space becomes as meaningful as the carved surface, often placed in light-exposed areas for dynamic shadowplay.

- The “relief chapel,” a hybrid form where a khachkar is embedded into a false architectural facade, with miniature columns, arches, and gables framing the cross.

These forms reflect not an idiosyncratic eccentricity but a sustained effort to give visual form to complex theological ideas—resurrection, cosmological harmony, sacred history—within the constraints of a single stone face.

Symbolism, Geometry, and the Theology of Stone

What makes the khachkar uniquely powerful is its ability to embody spiritual concepts without resorting to narrative. The cross is always central, but never alone; it is enwound in vines, set amid rosettes, flanked by abstract filigree that invites contemplation rather than story-reading. The very act of carving becomes theological: each gouge a prayer, each symmetry a meditation on divine order.

The geometry of the khachkar was never ornamental for its own sake. Armenian stone carvers employed principles of sacred geometry that echoed those used in church plans: proportions based on square roots, golden ratios, and star polygons. Some khachkars are effectively two-dimensional mandalas, their outermost rings and central points aligning with astronomical or liturgical cycles. In monasteries such as Sanahin, where khachkars stand near chapels, their carved patterns mirror the ribbed domes and blind arcades of the buildings they accompany.

This is no accident. The khachkar, though a freestanding object, was always in dialogue with architecture, with landscape, and with the community of the faithful. It invited not only individual prayer but collective memory. Many khachkars were raised to mark the end of a plague, a peace treaty, or a successful harvest—acts of thanks or atonement rendered not in liturgy alone, but in chisel and stone.

One famous example is the 1291 khachkar at Goshavank, carved by the master Pavgos. Its central cross blooms outward into a radial network of sixteen-pointed rosettes, framed by interwoven tendrils and framed inscriptions. Set into a stone wall facing the setting sun, it captures light and shadow with breathtaking precision. Even today, it stands as an argument in favor of sacred ornament: that form, when perfectly ordered, becomes a form of devotion.

The survival of thousands of khachkars through earthquakes, invasions, and centuries of erosion testifies to more than technical durability. It reveals a culture that entrusted its deepest hopes and fears not to passing media but to stone itself—cut, refined, and left standing under open sky. The khachkar is not just a religious symbol. It is Armenian theology given enduring, geometric form.

Illuminated Minds: Armenian Manuscript Painting

In a world where stone defined the sacred exterior, parchment became Armenia’s interior canvas—intimate, mobile, and infused with color. From the 5th century onward, the art of the Armenian manuscript became a medium not only of preservation but of transformation. The scribes and painters of Armenian scriptoria did more than transmit scripture and theology; they reimagined the visual and literary contours of a civilization, producing some of the most striking and intellectually rich illuminated manuscripts of the medieval world.

The Gladzor and Tatev Scriptoria

Armenia’s monastic universities were not passive repositories of ancient knowledge—they were laboratories of image and language. Chief among them were the Gladzor and Tatev scriptoria, both flourishing between the 13th and 15th centuries. At Gladzor, near modern-day Vayots Dzor, scholars produced manuscripts that combined textual precision with miniature paintings of extraordinary dynamism. The Gospel of Gladzor (1300s), now housed in the Matenadaran institute in Yerevan, features Evangelists with sharply angular drapery, buildings depicted in flattened, luminous perspective, and a palette dominated by cobalt, crimson, and gold leaf.

At Tatev, high in the southern mountains, the integration of theological education and artistic production reached a sophisticated peak. Here, monks trained in grammar, astronomy, logic, and theology also practiced the arts of pigment grinding, parchment preparation, and miniature painting. Manuscripts from Tatev display a cerebral aesthetic—icons arranged according to philosophical schema, text surrounded by diagrammatic ornament rather than free-flowing arabesque.

The organization of a manuscript page itself became a theological proposition. Marginalia weren’t random flourishes; they were interpretive frames. Rubrics weren’t just guides—they shaped the reader’s pacing and reflection. In Gladzor and Tatev alike, the manuscript was treated not only as a vehicle of content but as a spatial-temporal experience for the reader-viewer, where theology, poetry, and art converged.

Three visual hallmarks defined these scriptoria:

- Evangelist portraits set within architectural frames resembling Armenian churches, not classical Roman porticos.

- Use of Armenian script as ornament—elongated, interwoven letters forming visual rhythms along the margins.

- Scenes of Christ’s life compressed into single panels, with emphasis on theological clarity over narrative flow.

These were not works of private luxury. Though sometimes commissioned by princes, they were made to be read, studied, and sung aloud—integrated into the spiritual life of communities. Even the Gospel codices were often inscribed with detailed colophons, naming the scribe, the date, the donor, and the geographic circumstances of their creation. In doing so, the manuscripts embedded history within theology, memory within image.

Miniatures, Marginalia, and Theological Imagination

Armenian miniature painting belongs neither to the Greco-Roman naturalist tradition nor the Islamic arabesque lineage. Instead, it cultivated a hybrid style: flat yet rhythmic, narrative yet abstracted, intensely expressive within tight formal constraints. Figures in Armenian miniatures are often elongated, with massive eyes and stylized gestures. Backgrounds collapse into stacked architectural fragments or bold geometric fields. Depth is eschewed in favor of iconographic hierarchy.

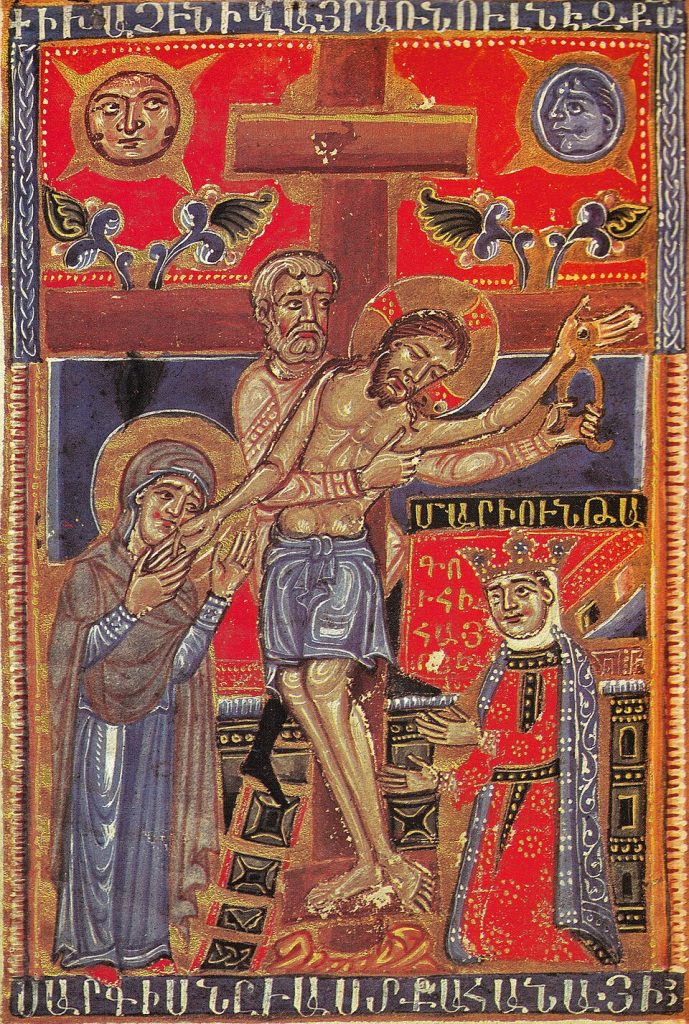

One of the most celebrated miniature painters, Toros Roslin of the 13th century, developed this visual language to unparalleled subtlety. Working primarily in the Cilician Armenian kingdom—a Christian polity in what is now southern Turkey—Roslin infused his Gospel manuscripts with courtly elegance, Byzantine influence, and indigenous clarity. His Zeytun Gospels (1256), now divided between Venice and Yerevan, display the Annunciation, the Crucifixion, and the Last Judgment with emotional restraint and architectural intelligence.

Roslin’s art is rich in symbolic detail. In his depiction of the Nativity, the cave of Christ’s birth resembles the basalt sanctuaries of Armenian monasteries. In the Crucifixion, Golgotha is rendered not as a rocky hill but as a stepped pyramid, with figures arrayed symmetrically like khachkar reliefs. Even when adopting Byzantine motifs, Roslin recasts them through the prism of Armenian space, theology, and form.

Marginalia in these manuscripts are equally revelatory. Dragons, birds, and interwoven vines serve both as ornament and commentary. Some margins contain not whimsical beasts but visual glosses on scriptural meaning: Adam hidden in a scroll beside Paul’s epistles, or Old Testament prophets gesturing toward scenes of Christ’s life. This interplay between main text and margin reflects a theological worldview in which all scripture interlocks, all image echoes deeper truth.

Three marginal traditions unique to Armenian manuscripts stand out:

- Interlinear micro-iconography: miniature saints and angels appearing between lines of scripture, bridging text and image.

- Glossed prayers: visual diagrams surrounding liturgical prayers, often in the form of crosses or concentric wheels.

- Genealogical trees, not of Christ’s lineage alone, but of scribes and disciples—charting the transmission of knowledge itself.

These manuscripts were not simply illustrated texts. They were objects of veneration, intellectual tools, and expressions of national identity. Their continued production into the early modern period—despite political fragmentation and external pressure—demonstrates the resilience of Armenian visual culture.

The Transmission of Color and Calligraphy Across Centuries

The pigments used in Armenian manuscripts were both locally sourced and globally connected. Reds from cochineal, blues from lapis lazuli or azurite, greens from malachite, and gold leaf—all were prepared in monastic workshops using recipes passed down in codices of their own. Each color bore symbolic weight: ultramarine for divine presence, red for martyrdom, green for paradise. The handling of these colors was both technical and theological, with each brushstroke conceived as a liturgical act.

Calligraphy in these manuscripts achieved levels of refinement comparable to Islamic or Carolingian scriptoria. Armenian uncial script, known as erkatagir, developed into a visual art form, its upright, block-like letters forming architectural structures on the page. Over time, more cursive forms such as notrgir and bolorgir were introduced, allowing for denser textual layouts, but always with rhythmic integrity.

What is striking is the integration of all these elements: color, script, image, and ornament. Armenian manuscripts do not compartmentalize decoration and meaning. Rather, every element of the page participates in an overall aesthetic of theological coherence. The page is a church in miniature: ordered, sacred, luminous.

Today, thousands of these manuscripts survive—many in the Matenadaran in Yerevan, others dispersed through Venice’s Mekhitarist library, the British Museum, and private collections. Each one is a microcosm of Armenian visual intelligence: careful, radiant, and indelibly alive.

Between Empires: Medieval Armenian Art in a Fractured World

Medieval Armenian art matured not in peace, but amid constant geopolitical tension. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, Armenian territories were buffeted by Arab caliphates, Byzantine emperors, Seljuk sultans, and Mongol khans. This political instability did not dampen artistic production—it diversified and sharpened it. Faced with imperial pressures and territorial fragmentation, Armenian artists cultivated a visual culture of resilience, synthesis, and precision. The result was an art that retained its national integrity even as it absorbed and transformed external influences.

Bagratid and Cilician Courts as Artistic Centers

Two royal courts—one in the north, the other in the far southwest—became critical engines of Armenian artistic life. The Bagratid dynasty, centered in Ani (present-day eastern Turkey), flourished in the 10th and 11th centuries. Ani, sometimes called the “City of 1,001 Churches,” was a walled metropolis rich in domed basilicas, monastic complexes, and palatial architecture. Its skyline of pointed drums and triangular gables was a visual declaration of sovereignty as well as piety.

Chief among Ani’s architectural triumphs is the Cathedral of Ani, completed around 1001 by architect Trdat, who also restored the dome of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. The cathedral’s interior is spacious yet grave, its pointed arches and slender piers anticipating Gothic solutions centuries later. Exterior blind arcades—vertical grooves that mimic columns—decorate its flanks, integrating rhythm and restraint in a unified façade.

To the west, the Kingdom of Cilicia (1080–1375), founded by Armenian nobles fleeing Seljuk invasions, became another crucible of art. In cities such as Sis and Tarsus, Armenian rulers built palaces and churches that combined native forms with Crusader and Byzantine motifs. Cilician manuscripts are especially rich in iconography, as seen in the Gospels of the Hethumids, with their fusion of Gothic frame motifs and Armenian theological clarity.

Three innovations distinguish Bagratid and Cilician courtly art:

- Monumental architecture built in rusticated volcanic stone, emphasizing mass over surface ornament.

- Use of polychrome masonry and decorative niches in façades to suggest depth without violating formal purity.

- Manuscript miniatures that adopt Western chivalric imagery while maintaining Armenian iconographic systems.

These royal courts were not insulated from each other. Despite distance and differing imperial pressures, they exchanged artists, theologians, and ideas, creating a pan-Armenian cultural network. Even when physical territory was lost, this network preserved a conceptual homeland through image and structure.

Byzantine Influence and Persian Tension

As Armenia lay between Byzantium and Persia, its visual culture often mediated these imperial aesthetics. From the west came the gold-leaf icons, marble revetments, and domed cruciform plans of the Byzantine tradition. From the east came more fluid ornamental vocabularies—arabesques, carpet patterns, and vegetal scrolls. Armenian artists did not choose between them. They adopted both, then restructured them within Armenian theological and formal priorities.

Byzantine influence is clearest in Cilician miniature painting. The painters of the Gospels of Zeytun and Gladzor employed Greek conventions for figures and drapery, yet their compositions remained ordered by Armenian ecclesiological logic. Angels hover symmetrically; saints are encased in architectural canopies that recall Armenian monastic courtyards, not Greek temples.

Persian influence was more abstract, manifesting not in figural imagery but in decorative technique. Armenian manuscript borders from the 12th century onward display arabesques, stylized pomegranates, and intricate latticework comparable to Islamic illumination. In the stone carvings of churches such as Haghpat and Sanahin, muqarnas-like stalactite motifs appear under arches, adapted for Christian settings without mimicking their original mosque contexts.

Three areas where Persian influence subtly altered Armenian form:

- Carpet page design in Gospel books, where geometry becomes more fluid and central motifs float in color-saturated fields.

- Stylized botanical forms in khachkar decoration, especially in Lori and Tavush regions.

- Architectural reliefs that blur the line between inscription and ornament, with kufic-style motifs transposed into Armenian script.

Despite political enmity, artistic dialogue endured. Armenian artists proved adept at filtering visual elements from imperial powers and redeploying them as theological statements or devotional tools. The aim was never aesthetic fusion for its own sake—it was survival of meaning under pressure.

The Painter Toros Roslin and His Legacy

At the height of Cilician Armenia’s cultural flourishing stood Toros Roslin, a master miniature painter whose works represent the summit of medieval Armenian manuscript art. Active in the mid-13th century, Roslin served at the royal court and likely trained in a monastic setting. His surviving manuscripts—particularly the Gospels of Zeytun (1256) and the Gospel of 1262—are technical marvels and theological documents alike.

Roslin’s genius lies in his ability to synthesize diverse influences without diluting the integrity of Armenian visual thought. His compositions borrow spatial recession from Byzantium, gesture from Gothic art, and color harmonies from Persian painting—but his figures are distinctly Armenian. Their expressions are serene, their gestures choreographed, their placement structured around theological hierarchy rather than pictorial realism.

In his Crucifixion scenes, Roslin avoids gore or sentiment. Christ appears upright, composed, flanked by Mary and John in poses of lamentation that echo khachkar symmetry. The visual field is dense but ordered: halos overlap but do not collide, garments fold but do not flow, light dazzles but never obscures. Every choice speaks of a controlled theology made visible.

Roslin’s legacy extended beyond style. He elevated the status of the manuscript painter from monastic artisan to court intellectual. Later scribes signed their work with pride, often invoking Roslin as precedent. His impact on Armenian art was both technical and moral: a model of how to remain visually Armenian amid political fragmentation and aesthetic seduction.

Even as Mongol incursions threatened the kingdom, Roslin’s pages offered a world of inner sovereignty—illuminated, ordered, and faithful. In a fractured world, his art held the nation together.

Faith, Silk, and Stone: The Art of the Armenian Diaspora

The Armenian diaspora did not begin with the 20th century. It was seeded over centuries of migration, forced and voluntary, stretching from the ports of the eastern Mediterranean to the cities of India, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe. What is remarkable is not simply that Armenians dispersed widely, but that they carried with them an artistic language so cohesive and resilient that it could take root in foreign soil without losing its structure. From Isfahan to Venice, Armenian communities reproduced their sacred forms in stone, textile, and pigment, generating a diasporic art that was at once portable and permanent, deeply local and unmistakably Armenian.

Merchants as Patrons of Church and Craft

Commerce—particularly the silk and spice trades—was the lifeblood of many diasporic Armenian communities, and it shaped their aesthetic priorities. Armenian merchants were not mere traders; they became cultural brokers, financing the construction of churches, schools, and scriptoria in their new host cities. They used wealth not for ostentation but to transplant Armenian ecclesiastical architecture and liturgical culture abroad.

Nowhere is this clearer than in New Julfa, a suburb of Isfahan established in the early 17th century by Shah Abbas I of Persia, who forcibly relocated thousands of Armenian artisans and merchants from the town of Old Julfa in Nakhichevan. In return for economic loyalty, Armenians were granted religious autonomy. Within decades, they had built Vank Cathedral—a stone basilica that fuses traditional Armenian forms with Safavid architectural language. Its exterior follows a simplified Armenian profile, while its interior explodes with Persian-style frescoes and tilework. It is a paradox resolved in stone: Armenian in liturgy and structure, yet resonant with the local visual idiom.

Diasporic Armenians functioned not only as cultural conservators but as artistic innovators. They established printing presses (such as the one in Amsterdam in the 1660s), introduced Armenian miniatures into European manuscript collections, and commissioned hybrid works that combined Armenian calligraphy with Italian, Persian, or Mughal visual elements. Their patronage supported:

- Fresco programs with Armenian iconography painted in Persian or Baroque styles.

- Gospels and Psalters written in Armenian but adorned with European landscape motifs.

- Ecclesiastical textiles woven in India or Iran but patterned with traditional Armenian crosses and vines.

This exchange was not passive mimicry. It was an assertive adaptation—an art of negotiation that retained theological and symbolic core while modifying surface grammar to communicate with new publics.

Architectural Echoes from Isfahan to Venice

Wherever Armenians settled in sufficient numbers, they built churches. These structures served not just as religious centers but as visual anchors of identity, signaling continuity amid alien cityscapes. What binds these churches together is not uniformity of form but consistency of principle: centralized plans, restrained ornament, and iconographic clarity.

In Venice, the Mekhitarist Order—founded in 1701—established a monastery on the island of San Lazzaro. The complex includes a church, library, and printing house, all built in a style that balances Western baroque with Armenian sacred design. Inside, the altarpiece features Armenian inscriptions; the architecture mirrors Roman Catholic norms but reinterprets them through a national lens.

In Eastern Europe, particularly in Lviv and Kamianets-Podilskyi, Armenian churches adapt Gothic and Baroque façades but retain internal features such as blind arcades, stepped apses, and khachkar-like carvings. These hybrids are not aesthetic compromises—they are testaments to the adaptability of Armenian architectural logic.

Three common features persist across diasporic Armenian churches:

- Inscribed khachkars placed prominently at entrances or within courtyards.

- Use of tuff or similarly colored stone to recall the volcanic palette of Armenia.

- Liturgical layout that prioritizes altar elevation and iconostasis arrangement in Armenian Orthodox style.

This architecture acted as a mnemonic device. Even if congregants no longer spoke fluent Armenian, even if generations were born abroad, the space itself taught them who they were.

Preserving Identity Through Aesthetic Continuity

Diasporic Armenian art is not merely about survival—it is about the preservation of coherence in dispersion. In a world where assimilation was both temptation and threat, art became a method of resistance. This resistance was not oppositional but rooted: a steadfast retention of form, symbolism, and ritual language that could be layered into other cultures without dissolving.

Manuscripts copied in New Julfa often reproduce older Armenian script and decoration styles with only minor local inflections. Textile arts—especially embroidered priestly vestments—adhere to ancient cross motifs and grapevine patterns regardless of whether they were sewn in Calcutta or Vienna. Even commercial documents, such as merchant account books, were sometimes illuminated with marginalia recalling medieval Gospel ornamentation.

One telling example is the tradition of memorial photography among Armenian communities in the Ottoman Empire and later in the diaspora. Photographs taken in Cairo, Beirut, and Paris often include khachkars or family members posed in front of embroidered Armenian banners. These compositions consciously mimic earlier manuscript page layouts—figures centered, flanked by symbolic objects, their poses echoing the calm severity of saints in illuminated texts.

In this way, even modern media were brought into the continuum. Diasporic Armenian art never abandoned the past. It carried it forward, sometimes in fragments, sometimes in full.

By the early modern period, Armenian artistic identity had proven itself extraordinarily elastic yet precise. It could inhabit a Persian dome or an Italian piazza, a merchant ledger or a votive painting—and still be itself. Diasporic art was not merely a shadow of homeland tradition. It was a second homeland: made by hand, preserved by choice, visible in form.

Eclipsed and Endured: Art Under Ottoman and Persian Rule

The long centuries of Armenian life under Ottoman and Persian dominion, stretching roughly from the 16th to the 19th centuries, are often narrated in terms of suppression and endurance. While it is true that Armenians lived under systems that denied them political sovereignty and often subjected them to institutionalized subordination, these same centuries also produced rich, nuanced, and hybrid works of art. Armenian creativity did not retreat under foreign rule—it adapted, cloaked itself in restraint, and found new channels. The visual arts, shaped by the twin demands of discretion and identity, took on subtler forms, moving inward and downward into domestic spaces, private devotion, and portable objects.

Secrecy and Survival in Sacred Art

Under the Ottoman millet system and similar Persian arrangements, Armenians were recognized as a protected religious minority—granted the right to worship, marry, and maintain their ecclesiastical hierarchy, but subject to limitations on public expression. This restriction particularly affected architecture. Churches could not dominate skylines, could not resemble mosques, and often had to be built below street level. In some cases, external decoration was prohibited altogether.

The result was a remarkable internalization of aesthetic energy. While the exteriors of many 17th- and 18th-century Armenian churches appear plain or even hidden, their interiors reveal finely carved woodwork, intricately painted apse ceilings, and elaborate iconostases. Art moved inside—literally and figuratively.

This dynamic is vividly seen in churches such as Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God) in Istanbul’s Kumkapı district. Behind a modest stone façade lies an interior rich with polychrome painting, marble inlay, and tiered wooden icon screens. The walls bear stylized vegetal motifs—vines, pomegranates, tulips—that resonate with both Armenian and Ottoman aesthetics. These visual strategies did not merely comply with restrictions; they reoriented artistic practice toward inwardness, toward the sacred privacy of community and soul.

Such environments cultivated a distinctive devotional mood: more hushed than triumphant, more introspective than didactic. Armenian artists working under Ottoman rule learned to speak in allusion rather than declaration, in code rather than proclamation. But the meaning was never lost. It was simply carried inward.

Urban Miniatures and Domestic Ornamentation

In both Ottoman and Persian contexts, Armenians often excelled in urban crafts and decorative arts—areas where they could work semi-anonymously, without overt religious content, and yet still embed their cultural identity. This led to a flowering of miniature painting, ceramics, and domestic ornamentation, much of it made for mixed or non-Armenian patrons.

Armenian miniature painters were employed in the Ottoman imperial studios (the nakkaşhane) alongside Muslim and other Christian artists. They contributed to secular illustrated manuscripts, court albums, and scientific treatises. While constrained by imperial style codes, some managed to insert subtle national motifs—cross-shaped flower stems, script in the margins, the occasional khachkar silhouette repurposed as architectural ornament.

In Persian cities such as Isfahan and Tabriz, Armenian artists played central roles in the luxury arts. They created:

- Textile panels woven with cross patterns that doubled as floral medallions.

- Silver incense burners shaped like miniature churches, sold in open markets.

- Illuminated secular texts whose borders mimic manuscript Gospel ornaments but tell stories of Persian romance or history.

The most intimate of these expressions occurred in the domestic sphere. Painted chests, embroidered bedcovers, and wall hangings often carried religious or historical motifs rendered in stylized form. A typical 18th-century Armenian home might contain images of Saint Gregory or Mount Ararat embedded within floral arabesques that satisfied Ottoman taste but carried encrypted meaning.

Art became a kind of second language—a way to speak identity softly in a world where loudness could provoke punishment.

Cultural Synthesis in Textiles and Metalwork

Nowhere did Armenian artists achieve such subtle synthesis as in textile and metalwork. These portable arts allowed for great visual richness within tolerable public bounds, and they often passed between communities, functioning as both commodity and cultural message.

Armenian embroidery from this period is characterized by saturated color, geometric border repetition, and iconographically dense central motifs. The “Tree of Life” pattern, ubiquitous in both Persian and Armenian visual traditions, became a favored motif, often with crosses disguised as branches or birds perched in cruciform arrangement. These designs graced altar cloths, bridal shawls, and even trade banners.

Metalwork, particularly in silver and copper, was a domain of special expertise. Armenian artisans produced:

- Chalices and censers that complied with Islamic restrictions on overt religious symbols yet contained hidden cruciform forms in their structural arrangement.

- Belt buckles and medallions inscribed with stylized Armenian script, sometimes functioning as covert talismans.

- Jewelry using coral and turquoise to form stylized Armenian initials, worn beneath clothing or integrated into bridal attire.

The synthesis here was not born of opportunism but of necessity—and brilliance. Armenian artists managed to produce work that pleased Persian and Ottoman taste, yet retained enough internal logic and form to remain distinctly their own. In doing so, they created a double-coded art: public in appearance, private in meaning.

This duality gave Armenian art of the period a rare subtlety and emotional range. Its colors may have dimmed, its scale may have shrunk, but its symbolic density and formal integrity only deepened. It was an art of endurance—not of martyrdom, but of mastery under constraint.

Catastrophe and Creation: The Genocide and Its Aftermath in Art

The Armenian Genocide of 1915–1923 did more than decimate a people—it tore through a culture, dismembering its institutions, silencing its voices, and scattering its survivors across the globe. Yet from this abyss emerged a body of art that did not merely mourn but witnessed, resisted, and reconstructed. Armenian artists, both within the shattered homeland and throughout the growing diaspora, turned to visual language not as escape but as confrontation. Their works became memorials, indictments, and means of psychic survival. The genocide, in annihilating so much, inadvertently generated a new mode of Armenian art: one grounded in trauma, testimony, and the fierce labor of remembrance.

Artistic Testimony from the Ruins

For many survivors and their descendants, visual art became a necessary extension of memory—especially when words failed or were denied by official histories. Some of the earliest artistic responses came from genocide survivors who had witnessed massacres, death marches, and destruction of entire towns. These were not academic painters or trained illustrators, but witnesses, often working in makeshift materials: charcoal, ink, scraps of paper.

One of the most haunting sets of images comes from Arshavir Shiragian, who documented atrocities in Turkey through stark pen drawings. Though schematic and crude, his works convey an immediacy and moral clarity impossible to mistake. Rows of bodies, ruined churches, mothers clutching children in a desert—these were not symbols but memories, rendered without romanticism.

By the 1920s and 1930s, more professional artists began to address the genocide’s legacy. In Beirut, Cairo, Paris, and Boston, diasporic Armenians created memorial works that combined personal grief with historical testimony. Often, these pieces appeared in community newspapers, religious calendars, and educational materials—art not just to be seen, but to be used.

Three recurring visual motifs emerged in this early phase:

- Ruined monasteries: both as literal reference to destroyed heritage and as metaphors for cultural loss.

- Desert marches: mothers and children walking into voids of sand, often framed by crescent moons or Turkish soldiers.

- Bleeding crosses: hybrid symbols of martyrdom and endurance, drawn from khachkar tradition but now rendered with flesh and wound.

This early art did not aim for aesthetic innovation. It aimed for moral record. In a world where few believed the survivors, the image became affidavit.

Diasporic Grief and Resilience Through Visual Culture

As Armenian communities established themselves in new lands, art became a way of rebuilding identity from the fragments of loss. Especially in the diaspora capitals—Los Angeles, Marseille, Beirut, Yerevan (later under Soviet rule)—a generation of artists born after the genocide inherited the trauma as secondhand memory. Their task was different from their parents’. They were not witnesses. They were interpreters.

Artists such as Paul Guiragossian in Lebanon, Jean Jansem in France, and Hovsep Pushman in the United States navigated a tension between personal style and inherited catastrophe. Guiragossian’s elongated, faceless figures—drifting in vertical crowds across narrow canvases—evoke exodus and dislocation without literal reference. Jansem’s expressionist portraits of suffering women, bent old men, and hollow-eyed children carry a psychic residue unmistakably linked to genocide, even when untitled.

In Los Angeles and Boston, genocide memorials began to emerge as architectural and sculptural forms. The 1965 memorial in Montebello, California, remains one of the most powerful: a stone tower of fractured planes, with names of lost cities carved into its base. Here, the khachkar tradition reemerges—but abstracted, stretched into the language of modern monumentality.

Diasporic art of this era worked on two fronts:

- As internal healing: providing a visual language for loss, identity, and community solidarity.

- As external communication: educating non-Armenians through visual testimony that circumvented political denial.

This second aim gained particular force in the aftermath of Turkey’s official denial of the genocide, a campaign that intensified from the 1980s onward. In response, Armenian artists began to create works designed for public confrontation. Exhibitions, installations, and performance art pieces invoked the genocide not just as tragedy but as unresolved wound, politically and spiritually.

Arshile Gorky and the Trauma of Memory

No figure more fully embodies the transformation of genocide into modern visual idiom than Arshile Gorky (born Vosdanig Adoian), whose early childhood in the Ottoman Empire was scarred by famine, loss, and flight. His mother died of starvation in his arms in Yerevan in 1919. He emigrated to the United States shortly after, remaking himself—name, style, even biography.

Gorky’s early paintings reference Armenian motifs and memory landscapes: dark portraits, angular still lifes, near-abstractions of homeland churches. But in the 1940s, he broke into full abstraction, becoming a forerunner of Abstract Expressionism. Works such as The Liver is the Cock’s Comb (1944) and Agony (1947) are explosively biomorphic, with forms that twist, bloom, and disintegrate—organic yet haunted.

Critics often debate how much Gorky’s work “represents” the genocide. He himself was reluctant to speak of it directly, preferring to cloak trauma in the vocabulary of memory, surrealism, and color. Yet the resonance is undeniable. In The Artist and His Mother (1936–1942), based on a photograph taken in Van before the genocide, Gorky reimagines the image in cold grays and angular forms. The mother’s face is featureless. The child’s body floats. It is not just a family portrait. It is a visual exhumation.

Gorky’s legacy in Armenian art is double-edged. He showed that trauma could be transmuted into universal form—yet he also embodied the price of that transformation. His eventual suicide in 1948 adds another layer to the role of art as both salve and scar.

Through Gorky, Armenian genocide art entered the international modernist canon—not as political message, but as aesthetic force. And yet the wound remained visible.

Soviet Armenia: Constraint, Innovation, and National Form

When Armenia became a Soviet Socialist Republic in 1920, it entered a paradoxical era of both cultural repression and creative renaissance. The Soviet system imposed ideological controls on all forms of artistic expression—demanding adherence to socialist realism, discouraging overt nationalism, and censoring religious content. Yet within these strictures, Armenian artists developed new strategies for expressing identity, memory, and form. Soviet Armenia’s art was neither wholly doctrinaire nor passively nostalgic. Instead, it negotiated between the language of the regime and the deep grammar of Armenian visual thought.

Socialist Realism and the Art of the Armenian SSR

Soviet cultural policy dictated that art must serve the people, uplift the working class, and affirm the inevitability of communism. In practice, this meant heroic murals of laborers, idealized portraits of collective farm life, and monumental depictions of Lenin and other party figures. In Armenia, however, these themes were often refracted through a uniquely national lens.

Painters such as Hakob Kojoyan and Gabriel Gyurjian incorporated Armenian folk motifs, traditional patterns, and landscape references into their officially sanctioned compositions. Kojoyan, who had studied in Munich and Paris, was one of the rare artists able to move fluidly between national and Soviet themes. His decorative panels and sketches for public monuments often included Armenian ornamental flourishes—grapevines, pomegranates, traditional embroidery patterns—even when illustrating industrial scenes.

More explicitly, artists used state commissions as opportunities to subtly reaffirm national identity. In public murals at railway stations, schools, and cultural halls, traditional Armenian musical instruments, garments, and architectural references appeared amid scenes of factory life and scientific progress. It was a quiet visual code: allegiance to the present, fidelity to the past.

Three thematic strategies characterized Armenian socialist realism:

- Encoding: inserting Armenian motifs into generic Soviet scenes as visual subtext.

- Regionalization: portraying Armenian landscapes—Mount Ararat, Lake Sevan—as settings for collective labor, grounding ideology in familiar terrain.

- Idealization of folk types: depicting Armenian peasants and workers as noble bearers of tradition and progress simultaneously.

This approach allowed artists to remain within ideological bounds while preserving a national aesthetic continuity that would have otherwise been erased.

Yerevan’s Monumental Art and Public Symbolism

Architecture and monumental sculpture in Soviet Armenia were particularly fertile fields for negotiation between form and message. The regime invested heavily in public works—cultural palaces, metro stations, and government buildings—many of which became canvases for hybrid architectural expression. While Moscow favored Stalinist classicism and later brutalist functionalism, Armenian architects often worked within a tradition of geometric clarity, stonecraft, and ecclesiastical restraint.

The 1950s and 60s saw a boom in monumental art in Yerevan, led by sculptors like Ara Harutyunyan and architects like Jim Torosyan. Harutyunyan’s work, especially his massive reliefs and statues, balanced socialist content with Armenian formal vocabulary. His statue of David of Sasun (1959), erected in front of Yerevan’s train station, embodies this balance: a folkloric hero presented in the heroic scale of Soviet myth, yet rooted in medieval Armenian epic tradition.

Public art was used to mark not only socialist victories but Armenian cultural milestones. The Matenadaran (built 1957–1963), Yerevan’s repository of ancient manuscripts, was designed to resemble a modern fortress. Its façade includes reliefs of Mesrop Mashtots (inventor of the Armenian alphabet) and other medieval scholars, carved in a bold, quasi-cubist style. The structure serves not just as archive, but as visual manifesto: Armenian identity persists through letters, stone, and scholarship.

Even metro stations, government offices, and apartment buildings were shaped by this dual logic. Volcanic tuff—pink, orange, black—was used in cladding to echo traditional Armenian masonry. Facades featured abstracted khachkar motifs, and interiors often included mosaics with folkloric themes subtly transformed into worker parables.

Three major public works exemplify this hybrid mode:

- The Cascade (1971–1980): a stepped public space and sculptural garden that blends brutalist geometry with Armenian spatial hierarchy.

- The Mother Armenia statue (1967): replacing a former Stalin monument, it recasts national defense in matriarchal form, referencing both Soviet militarism and Armenian maternal iconography.

- Yerevan Opera Theatre (1933–1953): designed by Alexander Tamanian, fusing neoclassicism with Armenian spatial logic, open arcades, and domed massing.

Through these forms, the city itself became a medium of continuity. Under ideological constraint, Armenian space-making persisted.

Martiros Saryan and Color as National Code

Among Soviet Armenian painters, no figure was more beloved—or more subversively national—than Martiros Saryan. Trained in Moscow and influenced by Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, Saryan developed a style characterized by vibrant color fields, flattened perspective, and an emphasis on lyrical, often symbolic, landscapes.

At first glance, Saryan’s work appears apolitical. His paintings—such as Armenia (1923), Yerevan in Spring (1935), or Pomegranate Tree (1958)—show no workers, no factories, no ideological scenes. But this apparent innocence was a visual strategy. By depicting Armenian landscape, flora, and light with near-mythic intensity, Saryan offered a counter-narrative to Soviet abstraction and propaganda. His colors became carriers of memory.

Saryan’s palette was saturated with national symbolism:

- Blue for Lake Sevan and divine clarity.

- Red for pomegranates, martyrdom, and fertility.

- Yellow and orange for the volcanic earth and sunlit resilience of Armenian life.

He often painted without figures—not out of apathy but to evoke presence through absence. A still table set for a meal, a flower vase in a sunlit room, a path through a village orchard—all these scenes carry emotional charge without literalism. They suggest survival, beauty, and the permanence of home, even when the homeland itself was under ideological siege.

Saryan’s influence extended beyond the canvas. His vision of color as mnemonic and mood became foundational for generations of Armenian artists navigating the contradictions of Soviet life. To paint a landscape was, in his idiom, to preserve a people.

By the time of his death in 1972, Saryan had become an unofficial national painter—his work displayed in public buildings, schools, and museums. Yet his legacy is not propaganda. It is the preservation of visual identity under the most complex constraints imaginable.

Independence and the Post-Soviet Renaissance

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 opened the gates to an uncertain but vital artistic rebirth in Armenia. Independence brought economic collapse, political instability, and war—but also a cultural reawakening. Freed from ideological constraints, Armenian artists began to reevaluate their past, confront suppressed traumas, and reassert national memory through new materials, forms, and institutions. The post-Soviet period has been marked not by a single dominant style but by a pluralism of voices—each negotiating the legacies of modernism, religion, diaspora, and war. If Soviet Armenia was about coded survival, independent Armenia has been about open reckoning and creative recklessness.

Memory, Revival, and the New Sacred

One of the most immediate shifts after independence was the visible return of religious and national symbols in public art. Churches were restored or rebuilt, khachkars once hidden or neglected were re-erected, and medieval visual languages re-entered contemporary art. But this revival was not merely nostalgic. Artists reexamined these forms with new urgency, treating them as living vocabularies rather than static heritage.

Architects returned to sacred models not out of rote tradition but as a means of spiritual re-rooting. The construction of Saint Gregory the Illuminator Cathedral in Yerevan (2001), for instance, was not a literal reproduction of medieval architecture but a bold, almost minimalist reimagining of Armenian church form. Its vast, unadorned stone surfaces and stark central dome evoke continuity and rupture simultaneously—honoring the past while acknowledging its loss.

In visual art, younger artists began incorporating ecclesiastical motifs into painting, installation, and performance. Crosses, Ararat silhouettes, medieval calligraphy—all reappear, but often disrupted, inverted, or collaged. This is not desecration; it is reactivation.

Artists in this revivalist mode pursued:

- Integration: weaving medieval ornament into contemporary textile and digital formats.

- Fragmentation: using shattered khachkars or manuscript pages as raw material for collage or sculpture.

- Theological irony: juxtaposing sacred forms with post-Soviet debris—gasoline cans, rusted rebar, urban detritus.

This tension between reverence and critique gave the new sacred a charged immediacy. It made clear that Armenian tradition was not a museum—it was a contested, living domain.

Artists Between Tradition and Experiment

A defining feature of post-Soviet Armenian art is its refusal to choose between tradition and experiment. Many of the country’s leading artists work across mediums, drawing from both national history and global movements. They reject essentialism, yet remain deeply Armenian in sensibility.

Samvel Baghdasaryan, known for his large-scale canvases and installations, often engages with the themes of memory and ruin. His pieces may include fragments of manuscript pages, metalwork, or khachkar imagery, layered with industrial paint or video projection. For Baghdasaryan, the past is not sacred but interrogated—reclaimed through abrasion, not veneration.

Other artists, like Tigran Tsitoghdzyan, have found success blending hyperrealism and conceptual portraiture. Tsitoghdzyan’s “Mirrors” series portrays ghostly female faces behind smeared handprints—images both intimate and anonymous. Though formally Western, the work resonates with Armenian diasporic themes: identity blurred, obscured, yet insistently present.

The Yerevan-based Artbridge and NPAK (Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art) galleries have provided platforms for these voices, allowing a generation of artists to engage issues once taboo: the genocide, corruption, emigration, and the emotional toll of transition.

Post-Soviet Armenian art has produced:

- Video installations addressing the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, blending documentary footage with poetic voiceovers.

- Abstract textile works that reinterpret medieval patterns in synthetic materials.

- Street art and graffiti using Armenian script as aesthetic disruption in urban space.

The aesthetic field is diverse, but the impulse is common: to reclaim control over the visual narrative of a nation that had been mediated for too long by others.

The Role of the Diaspora in Contemporary Art Scenes

The Armenian diaspora has played a complex, crucial role in the post-Soviet artistic renaissance. Wealthy donors helped fund cultural institutions, while diasporic artists brought fresh perspectives, techniques, and networks. At the same time, the tension between homeland and diaspora identities became a generative friction in the work itself.

Diasporic returnees, especially from France, the U.S., and Lebanon, collaborated with local artists on joint projects addressing shared trauma and divergent experience. These collaborations often explored questions of authenticity, hybridity, and what it means to be Armenian in a world where the nation itself is no longer the sole center of identity.

One emblematic example is the 2015 Armenity exhibition at the Venice Biennale, which won the Golden Lion for best national pavilion. Curated by Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg and featuring only artists from the diaspora, it presented works that dealt with memory, loss, and cultural continuity in profoundly varied modes—installation, film, sculpture, sound. The exhibit was housed in the Mekhitarist monastery on San Lazzaro, itself a symbol of diasporic endurance and creativity.

The diaspora’s impact has been:

- Infrastructural: funding art centers, scholarships, and museum renovations in Yerevan and beyond.

- Intellectual: introducing critical theory, feminist and postcolonial perspectives into Armenian art discourse.

- Aesthetic: bringing global techniques—digital media, conceptual frameworks—into dialogue with Armenian form.

This cross-pollination has not diluted Armenian art. It has expanded its compass. The post-Soviet Armenian artist may speak many languages, live in multiple cities, and use forms that are not obviously “national”—yet the underlying vision remains tethered to a deep historical and cultural source.

Today and Tomorrow: Contemporary Armenian Art on the World Stage

Change hums in the air—Armenian art today is a field alive with tension, ambition, and redefinition. As new generations assert themselves on the global stage, they carry forward narratives of tradition, trauma, and transformation. This moment is neither a culminating apex nor a rupture—it’s an open horizon, a moment of self-questioning, and reinvention. The global presence of Armenian art now reflects its complex identity: diasporic yet rooted, experimental yet tradition-aware, local yet cosmopolitan.

The Venice Biennale and Global Recognition

Armenian participation in the Venice Biennale is emblematic of this global emergence. Following the success of the 2015 Armenity pavilion, Armenia returned in subsequent editions with works that speak across borders. The 2022 presentation by artist Arshak Uzunyan explored Armenia’s reconciliation with farcical memory—reconstruction, mimicry, and selective forgetting—through layered architectural installation. These biennale exhibits are notable not just for their visibility but for their refusal to reduce Armenian identity to single stories. They present complexity, contradiction, and open questions.

Elena and Serob Yeghiazaryan’s 2028 project—installing interactive sculptural forms that hum with the sounds of diaspora languages—aimed to transform public experience of Armenian belonging. Through such interdisciplinary, multi-sensory approaches, contemporary Armenian artists seize global platforms not merely for exposure, but for genuine participation with global discourses on migration, memory, and belonging.

Ecology, Identity, and Geopolitical Trauma in New Works

In Yerevan’s galleries and residencies, a wave of works examines the convergence of ecology and identity. The Armenian Highlands—its endemic trees, water crises, and seismic patterns—have become focal points in installations that bridge ancient landscape reverence and current climate urgency. Artists like Larissa Sansour have deployed cinematic video and augmented-reality mobile overlays to recount eco-narratives tied to Mount Ararat, simulating virtual pilgrimages that span territories now divided by war or politics.

Geopolitical trauma, most notably from the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, also underpins many contemporary works. Sculptor Davit Petrosyan uses spent ammunition and collapsed mine fencing, reshaping them into hope-thorned vines and abstracted khachkar forms. Painter Lilit Soghomonyan incorporates bullet motifs into canvases of pastoral fields—beautiful landscapes scored with lines of conflict. These works refuse aesthetic distance: they are meant to be experienced as confrontations with living grief and contested futures.

Digital Revival of Ancient Motifs and Modern Myth-Making

As the world digitizes, Armenian artists are translating their visual heredity into new formats—VR, AR, NFT, and generative art. In 2023, the collective Khachkar 2.0 released a VR experience allowing participants to “visit” a digital necropolis of floating, animated khachkars. Each cross-stone responds to sound and movement, weaving real-time visual patterns based on user presence. It’s an embodiment of tradition reimagined for virtual space.

Generative artworks by Anahit Stepanyan use algorithms to redraw Armenian manuscript patterns in infinite variation, referencing scriptoria forms from Gladzor and Tatev. In doing so, these works evoke the manuscript’s dual life—man-made and divine, fixed and living—while speaking in the optical aesthetics of code.

NFT initiatives have also appeared, notably Ararat Index, a platform where artists mint digital calligraphy, manuscript-style loops, or Ararat-laid cityscapes, sharing royalties with heritage institutions. It’s a contentious space, where questions of commodification and cultural stewardship collide. But it signals something crucial: Armenian art is not just reviving heritage, it’s entering global debate on ownership, authenticity, and digital futurism.

The art of Armenia today challenges expectations—of what is national, what is modern, and what is universal. Its practitioners work across media, ideologies, and geographies, questioning old frames and shaping new ones. The story of Armenian art has always been one of adaptation and retention; its current chapter is its most daring yet: a visual reckoning with belonging, rupture, and the uncharted terrain of tomorrow.