In the grand story of 19th-century art, many names have been immortalized for their brushwork, color theories, and stylistic revolutions. Yet woven into this same history are the quiet, often heartbreaking stories of real human beings whose lives were treated as secondary to the ambitions of artists. Among them stands Annah la Javanaise, a young girl from Java whose brief and tragic association with Paul Gauguin offers a sobering window into a dark undercurrent of the era. Annah’s story is not one of mutual inspiration, but of exploitation — a tale that demands to be told with honesty, dignity, and moral clarity. Her life reminds us that beauty separated from virtue often leads to corruption rather than true artistic greatness.

Born into a time of colonial rule, Annah was far from the salons and studios of Paris where her fate would eventually lead. She was not a willing muse nor a professional model seeking fame; she was a vulnerable child caught in the tangled ambitions of an aging Frenchman seeking escape from his failures. Gauguin’s fascination with the so-called “primitive” and “exotic” ultimately made Annah a living symbol for his personal rebellion against the moral norms of Christian Europe. Yet what he saw as liberation was, in truth, a profound betrayal of duty and honor. In rediscovering Annah’s story today, we are called not to elevate Gauguin’s fantasies, but to remember and respect the innocent life so carelessly treated.

Artistic movements of the late 19th century were often intoxicated by a false ideal of freedom — freedom from tradition, from morality, from duty. Figures like Gauguin were lionized for their pursuit of self-expression at any cost. Yet such a view is a distortion of the proper role of art, which should elevate the soul, not trample upon it. In honoring Annah’s memory, we affirm that beauty and truth must always walk hand in hand, and that even the brightest colors on a canvas cannot mask the darkness in the heart of the painter.

The story of Annah la Javanaise is a call to return to first principles: that every human life has an inherent dignity bestowed by God, not by worldly fame. Artists are stewards, not owners, of the human images they portray. When they forget this sacred charge, they may create paintings that dazzle the eye, but they leave behind a legacy of moral ruin. Through careful study and honest remembrance, Annah’s life can yet shine as a testimony against such betrayal — a small light of truth in a world too willing to excuse sin in the name of genius.

The Life and Origins of Annah la Javanaise

Annah’s precise birth date is not recorded, but historians generally place her birth around 1879 or 1880, on the island of Java, then part of the Dutch East Indies. Java, rich in cultural traditions and natural beauty, had long been subjected to European colonial rule by the 19th century, with Dutch control formalized in the early 1800s. Life for native families under colonial governance was marked by economic hardship and social disruption, especially for women and children. Many young girls, like Annah, faced extreme vulnerability, especially to exploitation by colonial authorities or foreign adventurers.

There is little documentation regarding Annah’s family background, though it is likely she came from humble circumstances. Colonial societies often tore apart traditional family structures, making children easy targets for those seeking servants, concubines, or, as in Annah’s case, artistic subjects. The Dutch colonial government officially abolished slavery in 1860, but many exploitative labor and domestic arrangements persisted well into the 1890s under different guises. It would not have been unusual for a young Javanese girl to be placed into the service of Europeans under conditions that were effectively little better than bondage.

By the early 1890s, Annah somehow found herself in France, likely brought either by traders, colonial families, or intermediaries involved in Paris’s fascination with the exotic. Paris at the time was hungry for so-called “Oriental” culture, as reflected in music, painting, and fashion. Young women from the colonies were often viewed not as individuals, but as living decorations, their humanity disregarded for the sake of novelty. It was in this atmosphere of casual exploitation that Annah’s path crossed with Paul Gauguin’s, sealing her fate in history.

The tragedy of Annah’s life was set in motion not simply by poverty or colonialism, but by the moral blindness of a society that had lost its sense of duty toward the vulnerable. In Christian teaching, the protection of the weak is a sacred charge, yet the secular culture of late 19th-century Paris had largely cast aside such responsibilities in favor of indulgence. Annah’s journey from the tropical beauty of Java to the cold urban sprawl of Paris was not a tale of opportunity, but of abandonment.

Paul Gauguin’s Encounter with Annah

Paul Gauguin, born in Paris in 1848, was by the early 1890s a man increasingly marked by failure and personal ruin. Having left a career as a stockbroker in the 1880s to pursue painting full-time, he faced constant financial hardship and social isolation. By 1891, Gauguin had already made a brief and unsatisfying trip to Tahiti, returning to Paris disillusioned but still determined to embody the image of the rebellious, misunderstood genius. It was during this tumultuous period that he encountered Annah, likely in late 1892 or early 1893.

Reports suggest that Gauguin either purchased or otherwise arranged to have Annah live with him, acting simultaneously as a domestic servant, model, and concubine. Annah would have been around 13 or 14 years old at the time, an age at which her innocence should have been fiercely protected. Instead, she became yet another possession in Gauguin’s growing inventory of exotic trophies. His diaries and letters from the period reveal a chilling indifference toward the moral implications of his behavior, cloaking sin beneath the language of artistic freedom.

Gauguin’s life during this period was marked by squalor. He lived in a modest apartment at 6 Rue Vercingétorix in the Montparnasse district, often behind on rent and reliant on the charity of art dealers like Ambroise Vollard. Far from the romantic image of the free-spirited artist, Gauguin’s Paris years reveal a man deeply ensnared by debt, illness (including signs of early syphilis), and spiritual decay. Into this environment, Annah was placed — a child among desperate adults.

Annah’s daily life in Gauguin’s household is not well-documented, but given the realities of the time and Gauguin’s writings, it can be reasonably surmised that she was treated more as an object than as a person. Rather than receiving the care and education due to her youth, she was used for physical pleasure and artistic display. This grave betrayal of duty would repeat itself throughout Gauguin’s later life, but with Annah, it was already fully underway.

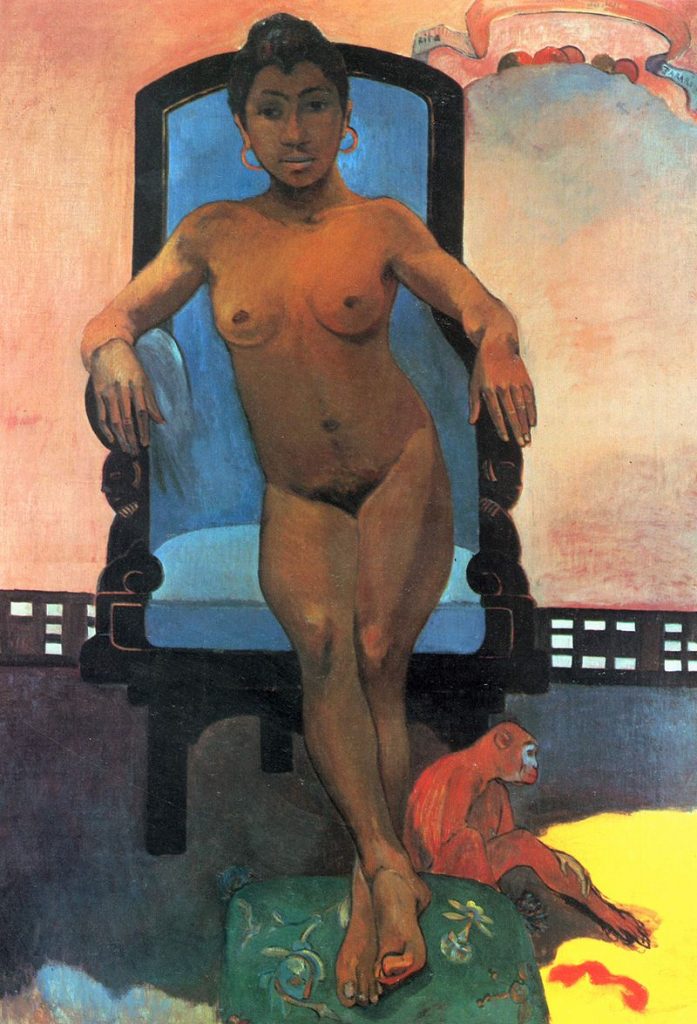

The Portrait: Analyzing “Annah la Javanaise”

Annah la Javanaise, painted in 1893, captures the young girl reclining languidly on a divan, a loose robe carelessly draped over her frame. The painting measures approximately 73 by 92 centimeters and is currently housed in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum in Copenhagen. Gauguin’s use of muted reds, earthy browns, and deep greens gives the work a heavy, oppressive atmosphere, in sharp contrast to the lively innocence one might expect of a girl her age. The black cat resting near Annah’s leg introduces a further symbol of sensual danger, a motif common in European art.

The girl’s expression in the portrait is striking — a knowing, almost jaded look that belies her youth. It is difficult to believe that such an expression was natural; rather, it seems the product of Gauguin’s coaching, shaped to meet the expectations of a European audience hungry for “exotic” titillation. Her robe, loosely tied, reveals one bare leg and hints at her chest, exploiting her vulnerability under the guise of artistic freedom. The entire composition reduces Annah from a living soul to a symbol of fantasy and moral rebellion.

Technically, the painting demonstrates Gauguin’s skill in composition and color harmony, yet these gifts are marshaled toward a corrupt end. Rather than elevating the viewer toward a higher ideal of beauty and virtue, the painting wallows in the fallen human condition, celebrating the artist’s own sins. In this way, Annah la Javanaise stands as a cautionary example of how great technical ability, divorced from virtue, can lead to spiritual ruin rather than artistic greatness.

There is no denying the visual power of the painting, but true discernment demands that viewers see beyond the surface. Annah was not a willing participant in some grand artistic experiment; she was a child manipulated into serving the broken dreams of a man who had long since abandoned any true sense of honor. Thus, Annah la Javanaise must be viewed not as a masterpiece of exoticism, but as a sorrowful record of exploitation.

Exoticism and the Corruption of Art

In the late 19th century, France was swept up in a wave of “Orientalism,” a fascination with cultures deemed exotic and mysterious by European eyes. Painters, writers, and composers alike turned their attention to the East, Africa, and the Pacific Islands, portraying these lands as sensual, primitive, and free from the restraints of Christian morality. Yet behind the colorful depictions of faraway lands lurked a troubling reality: real people, like Annah, were treated not as human beings but as symbols of European fantasy. Artists who should have pursued truth and beauty instead indulged in distorted, sinful portrayals of innocence corrupted.

Paul Gauguin was deeply influenced by this cultural trend. Rather than confronting the moral demands of the faith he had abandoned, he sought refuge in romanticized visions of so-called “primitive” life. To him, girls like Annah represented not only physical attraction but a broader escape from the responsibilities of Western civilization. This attitude, while common among the decadent circles of Paris, stood in stark contradiction to the true Christian understanding of man’s duties toward the weak and the innocent. In choosing indulgence over duty, Gauguin embodied the tragic corruption that so often accompanied exoticism.

The portrayal of young colonial subjects as objects of sensuality was not unique to Gauguin but was a broader sickness within the art world of the time. French society, intoxicated by its own pride and power, lost sight of virtue in favor of aesthetic thrills. Many artists presented themselves as visionaries, yet in truth they served only their own passions. The cultural celebration of exoticism masked a profound moral decay that, when viewed through the lens of truth, cannot be excused or glorified.

Annah la Javanaise thus serves as a tragic symbol of what happens when art is separated from moral responsibility. The painter’s brush can elevate or it can degrade, depending on the heart that guides it. Gauguin’s betrayal of Annah is not merely a personal failure, but a condemnation of an entire artistic movement that celebrated sensation over sanctity, indulgence over honor.

Annah’s Fate: Lost to History

After her brief time in Gauguin’s household, Annah la Javanaise disappears almost entirely from the historical record. Gauguin himself left Paris in June 1895, returning to Tahiti in search of new inspirations and new victims for his corrupt appetites. It is widely believed that Annah, abandoned by Gauguin, was left to fend for herself in a foreign land where she had no family, no protector, and no standing. The silence of history concerning her later life is itself a tragedy, a testament to the indifference of a society that discarded her once her novelty had worn off.

The likely outcomes for Annah were grim. Paris in the 1890s offered few opportunities for a young foreign girl with no resources or social support. Many such girls were forced into prostitution, domestic servitude, or beggary. It is unlikely that Annah, so cruelly used at a young age, was ever able to reclaim the dignity and stability that had been stolen from her. Her story ends not with triumph or redemption, but with a void — an absence that speaks volumes about the human cost of artistic selfishness.

Annah’s erasure from the historical record stands as an indictment of the art world and the broader society that valued the artist’s fame over the fate of the vulnerable. Museums, critics, and biographers for decades celebrated Gauguin’s work while ignoring the real lives he harmed. Even today, many accounts of Annah la Javanaise mention her only in passing, as a mere footnote in Gauguin’s career rather than as a child whose life was tragically deformed by sin and selfishness.

In honoring Annah’s story today, the goal must not be to sensationalize her suffering but to restore a measure of the dignity she was denied. Every human soul is precious, made in the image of God, and deserving of protection and honor. The fact that Annah’s life ended in silence only deepens the moral responsibility of those who study history: to remember, to mourn, and to learn.

Gauguin’s Flight to Tahiti

Paul Gauguin’s departure for Tahiti in 1895 marked the beginning of a new and even darker chapter in his life. Although he marketed his journey as a quest for artistic purity and escape from European corruption, the reality was far more sordid. Gauguin quickly resumed his pattern of exploiting young girls, often entering into so-called “marriages” with native girls as young as thirteen. He contracted syphilis, which he would carry and spread throughout his remaining years, even as he continued to paint idyllic visions of island life.

Gauguin’s pattern of behavior abroad was deeply rooted in the same moral blindness that had led to his betrayal of Annah. Rather than seeing the islanders as fellow human beings with dignity and rights, he viewed them through the same selfish lens of exoticism and personal gratification. His paintings from this period — colorful, seductive, and richly detailed — often mask the tragic reality of exploitation that lay behind them. The myth of the noble savage became his justification for actions that would, under any right standard, be recognized as grave sins.

His personal writings from this time reveal a man increasingly unmoored from reality and morality. In his journal Noa Noa, Gauguin describes his relationships with young girls in detached, almost boastful terms. There is no repentance, no recognition of the harm he inflicted. Instead, he presents his actions as part of a grand artistic and spiritual adventure — a tragic self-deception that the art world, for too long, willingly accepted without question.

The flight to Tahiti was not an escape from the decadence of Europe; it was merely a continuation of it under a different sky. Gauguin’s life, when viewed honestly, is a story not of heroic rebellion but of spiritual collapse. The suffering of the young — from Annah la Javanaise to the many unnamed island girls — is the true legacy of Gauguin’s so-called liberation from Western norms.

Modern Appraisals: Seeing Through the Myth

In recent years, there has been a growing movement among historians and critics to reassess Paul Gauguin’s legacy with greater honesty. No longer content to excuse his sins in the name of “artistic freedom,” many now recognize the moral failings that undergirded his work. Institutions such as the Tate Modern and the National Gallery have begun framing Gauguin’s exhibitions with warnings about the exploitation involved in his career. This is a welcome development, though it is long overdue.

However, there remain voices within the art world who continue to downplay Gauguin’s misdeeds, insisting that his paintings should be separated from his personal life. Such an argument is deeply flawed. Art is an expression of the soul, and when the soul is corrupted, the art — no matter how visually beautiful — bears the stain of that corruption. True greatness in art must be measured not merely by technique, but by moral and spiritual vision.

Critics who seek to defend Gauguin often speak of “different times” and “different cultures,” attempting to relativize his actions. Yet virtue and sin are not creatures of fashion; they are rooted in eternal truths. The command to protect the young, to honor the innocent, and to act with chastity and dignity has always been known, even if it was often disobeyed. To dismiss Annah’s suffering as a mere artifact of history is to commit a second injustice against her.

The time has come for the art world to embrace a standard of truth that honors both beauty and moral responsibility. To see through the myth of Gauguin is not to erase his paintings from history, but to see them clearly — both their technical brilliance and their moral failures. Only through such honesty can we truly respect the lives of those, like Annah la Javanaise, who were sacrificed on the altar of selfish ambition.

Honoring Annah’s Lost Dignity

Annah la Javanaise was not merely a model, a muse, or a footnote in art history. She was a child with a soul, a young life full of potential that was gravely wronged by those who should have protected her. Her story, once obscured by layers of romanticized fantasy, now stands as a stark testament to the enduring importance of truth, virtue, and moral responsibility. Remembering Annah is an act of justice, a small but meaningful way to restore some measure of the dignity she was denied.

Artistic achievement can never excuse moral failure. The painter’s talent, no matter how dazzling, must be weighed against the treatment of the subjects who made his work possible. Annah’s life reminds us that the true measure of an artist is not only the beauty he creates, but the goodness he preserves. In failing Annah, Gauguin forfeited the right to be celebrated without serious moral reckoning.

Today, as museums and scholars revisit the lives behind the paintings, Annah la Javanaise calls out for remembrance. She deserves more than a fleeting mention; she deserves to be seen as a real person, precious and irreplaceable, whose life mattered infinitely more than the brushstrokes that captured her image. Her lost childhood is not just a historical footnote — it is a wound that demands acknowledgment and sorrow.

In honoring Annah la Javanaise, we recommit ourselves to the truth that beauty must always serve virtue, and that no artistic triumph can ever justify the betrayal of the innocent. May her memory inspire a generation that seeks not only greatness in art, but greatness of soul.

FAQs

Who was Annah la Javanaise?

Annah la Javanaise was a young girl from Java, likely born around 1879–1880, who was brought to France and became the model and mistress of Paul Gauguin around 1893 when she was approximately 13 or 14 years old.

How did Annah meet Paul Gauguin?

During his impoverished years in Paris in the early 1890s, Gauguin encountered Annah, likely through colonial intermediaries or social circles fascinated by the “exotic.” He brought her into his household under deeply exploitative conditions.

What happened to Annah after Gauguin left Paris?

Annah disappears from the historical record after Gauguin’s departure for Tahiti in 1895. Her later life remains unknown, but given the hardships faced by foreign girls in Paris, her prospects were sadly bleak.

What does the painting “Annah la Javanaise” depict?

The painting shows Annah reclining on a divan with a loose robe, accompanied by a black cat. Her pose and expression reflect the tragic exploitation behind the seemingly exotic scene.

Why is Annah’s story important today?

Annah’s story reveals the moral failures that accompanied much of the 19th-century fascination with exoticism. It calls for a truthful reassessment of artists like Gauguin, recognizing both their technical skill and their grave moral shortcomings.

Key Takeaways

- Annah la Javanaise was a real young girl, not merely a “muse,” who suffered exploitation at the hands of Paul Gauguin.

- Her life underscores the dangers of separating art from moral responsibility and virtue.

- Gauguin’s portrayal of Annah reflects a broader cultural decay in late 19th-century France, where the innocent were often sacrificed for indulgence.

- Modern critics are beginning to reassess Gauguin’s legacy with greater honesty, but much work remains to be done in honoring the lives of those harmed.

- Annah’s memory serves as a permanent reminder that the pursuit of beauty must never come at the cost of truth, dignity, and the sacred value of human life.