The foundation of Adelaide was not merely a political or geographic act—it was a conceptual and aesthetic one. More than any other Australian capital, Adelaide was imagined first as an ideal, a city shaped by Enlightenment ambition and visualized through maps, drawings, and painted landscapes before it ever took material form. The city’s artistic history begins here: in the intersection of power, planning, and picturesque invention.

Drawing the Ideal Settlement

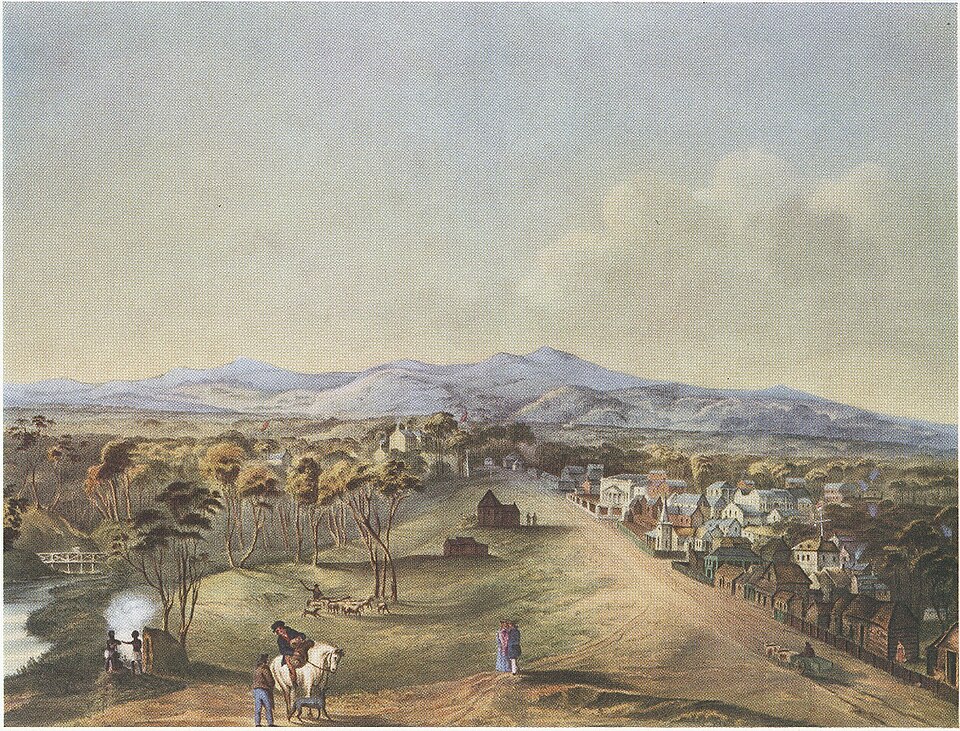

Colonel William Light’s 1837 plan for Adelaide is often cited as one of the earliest instances of urban design in the Australian colonies based on aesthetic principles. Light, who had trained as a draftsman and surveyor, envisioned a gridded city bordered by parklands—an urban ideal filtered through classical European taste, Enlightenment rationalism, and his own experiences in the British military and diplomatic corps. His vision was not spontaneous. It was shaped by a wider colonial tradition in which cartography, topographical drawing, and aesthetic landscaping were integral to the process of colonization itself.

Early maps of Adelaide, with their balanced geometry and carefully demarcated zones for civic, religious, and commercial functions, functioned as visual arguments. These weren’t neutral records but aspirational images—acts of persuasion meant to demonstrate order, civility, and harmony to investors, settlers, and government sponsors. Light’s sketchbooks, preserved in various archives, reveal a hybrid practice—part survey, part artistry. His views of the Adelaide plains echo the compositional balance of 18th-century British landscape artists such as Paul Sandby, where horizon lines, rivers, and hills are organized with painterly care.

This origin point sets a distinctive tone for Adelaide’s visual culture. Unlike Sydney or Hobart, cities that evolved around harbors with irregular contours and organic sprawl, Adelaide was a picture before it was a place—a visual argument before it was a lived reality.

British Aesthetics on Kaurna Land

The tension between European ideals and South Australian realities becomes most vivid when one considers what was displaced, ignored, or overwritten in these early artistic visions. Adelaide was founded on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people, whose cultural and spiritual ties to the landscape were neither recognized nor represented in colonial art of the period. Where Kaurna knowledge mapped meaning through songlines and seasonal cycles, the colonial eye prioritized measurable space, ownership, and aesthetic “improvement.”

Early settler artists, many of them amateur or self-taught, engaged in a kind of visual translation: turning unfamiliar flora, geological formations, and weather conditions into compositions that fit European expectations. Gum trees were rendered as tidy or symmetrical; bushland was softened into bucolic pasture; dry creeks and jagged escarpments were reframed to resemble English riverbanks or Alpine foothills. The unfamiliar was made familiar by force of brush and pencil.

One illustrative example is the work of George French Angas, whose mid-19th century illustrations combined scientific observation with the theatrical conventions of travel illustration. His drawings of Kaurna men and women, while detailed and ostensibly respectful, are framed through a Romantic lens that exoticizes rather than explains. The surrounding landscapes—cleanly composed, sparsely populated, and subtly idealized—convey a vision of South Australia as waiting to be cultivated.

Yet even within this genre, one occasionally encounters friction. Artists struggled to reconcile the dryness, light, and scale of the land with the conventions they brought from Europe. There is a subtle awkwardness in many early watercolours—a hesitation in the rendering of soil colour, a flattening of depth, or a misreading of eucalyptus forms. These moments of technical failure are, paradoxically, some of the earliest instances where South Australia asserts itself as visually resistant to imported formulas.

Surveyors, Topographers, and the Art of Possession

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, as South Australia expanded its interior settlements and agricultural frontiers, the role of the artist became closely linked to that of the surveyor and the geologist. Expeditions into the Flinders Ranges, the Barossa Valley, and the Murray River system often included draftsmen whose task was to render not only topography but potential. These were images made for assessment, investment, and eventual transformation.

In this context, art served as a kind of legal fiction. A painted or engraved view—especially one that emphasized order, abundance, or navigability—implied control. One could argue that possession began not with fencing or farming but with the act of picturing. The documentation of a creek bed, a stand of trees, or a mineral outcrop was not neutral: it was an assertion of value, destined to circulate in colonial offices, scientific journals, and illustrated travel accounts.

Artists like S.T. Gill, who moved freely between reportage, caricature, and picturesque landscape, played a significant role in shaping perceptions of the colony both within and beyond its borders. His images of bush life, sheep stations, and goldfield camps contributed to a growing mythology of South Australia as industrious, moral, and modern. Even when his tone was satirical—as in his sketches of drunken settlers or chaotic road-building efforts—Gill reinforced the idea that this was a society in motion, developing toward civility.

What is striking in many of these early images is their scale and framing. Even vast open country is rendered as manageable. The horizon is near; the human figure is always present. Unlike later Australian art, which would embrace vastness, emptiness, and strangeness as aesthetic values in their own right, early South Australian images cling to proximity. The land is always just tamed enough.

Adelaide’s artistic history begins, then, with a contradiction. It is the city most consciously designed, mapped, and visualized in advance—and yet it sits atop older, unacknowledged systems of meaning and representation. Its early art records an ambition to bring Europe with it, to render the unfamiliar legible, and to establish possession through picture-making. The land answers back—not with resistance, but with complexity. That complexity would take generations to acknowledge, and longer still to understand.

Early Institutions and the Rise of Cultural Infrastructure

Before Adelaide had a cathedral, it had an art society. Before its cityscape filled with statues and memorials, it built halls for lectures, galleries for exhibition, and reading rooms for self-improvement. In the 19th century, Adelaide’s civic leaders were unusually preoccupied with the cultural life of the colony—not as ornament, but as structure. They believed art was not merely an embellishment to society but a foundation of its moral and intellectual health.

The Birth of the South Australian Society of Arts

Founded in 1856, the South Australian Society of Arts (SASA) was the earliest formal art institution in Australia, predating both Sydney’s and Melbourne’s equivalents. It emerged not out of a bohemian movement or spontaneous creative flowering but through the energy of administrators, educators, and scientific men. It was, in many ways, an instrument of improvement. Modeled on the Royal Society and other British civic bodies, SASA was part club, part academy, and part exhibition organizer.

Its first exhibitions were held in the Legislative Council Chamber—a telling detail. In Adelaide, art entered public life through proximity to government, not rebellion against it. Early shows included landscape paintings, botanical studies, architectural sketches, and mechanical diagrams. The lines between fine art, science, and craft were porous. An engineer might submit a technical drawing; a schoolgirl might exhibit a floral watercolour. These exhibitions reflected the values of the colony’s middle class: diligence, refinement, progress.

While many of the artists were amateurs—clergymen, surveyors, schoolteachers—some would achieve enduring reputations. The German-born painter Charles Hill, who taught at Adelaide’s School of Design and helped lead SASA in its early years, emphasized discipline and academic technique. His landscapes, though conventional, revealed a meticulous understanding of light and foliage rare among colonial artists. More importantly, Hill trained a generation of local draughtsmen and painters, embedding an aesthetic culture in the city’s educational DNA.

SASA also created a rhythm to Adelaide’s artistic life. Annual exhibitions, judged by committee and occasionally opened by the governor, gave artists regular opportunities to present work, while allowing the public to see their own land through aesthetic eyes. This civic model would prove durable, shaping South Australian cultural identity well into the next century.

Libraries, Museums, and the Victorian Cult of Refinement

The appetite for institutional culture in 19th-century Adelaide extended well beyond painting. The city’s cultural infrastructure grew rapidly in the decades following settlement, fueled by a literate population and a powerful belief in the civilizing force of knowledge.

The Mechanics’ Institute, established in 1838 and later absorbed into the Adelaide Library, became a cornerstone of public learning. Its lectures and reading rooms were well attended, and its ethos—self-education, rational inquiry, moral uplift—reflected the broader ambitions of the colony’s leadership. Unlike Sydney or Melbourne, where convict origins cast a long shadow, Adelaide’s founders saw their city as a social experiment: a place where culture could grow without corruption.

By the 1860s, this philosophy had a physical footprint. The South Australian Institute building, completed in 1861 on North Terrace, housed the public library, museum, and art exhibitions under one roof. It was a bold gesture of centralization and intellectual seriousness. Its architecture, a blend of classical symmetry and colonial austerity, made the building itself a kind of didactic statement: that knowledge was to be ordered, displayed, and shared.

Visual culture flourished in these spaces. The museum’s natural history displays, including Aboriginal artefacts (often interpreted through flawed 19th-century anthropological frameworks), were among the earliest such collections in the colonies. The library exhibited rare books and prints. And the adjacent exhibition halls hosted everything from international loan shows to amateur art competitions.

Three things stand out from this period:

- Adelaide’s cultural institutions were unusually interconnected. Art, science, and education developed side by side.

- Public funding was significant. The colonial government saw value in culture as a civic investment, not just a private pursuit.

- The city’s scale—neither a metropolis nor a frontier outpost—allowed these institutions to be accessible, central, and visible.

This integration helped produce an unusually cohesive artistic climate, one that prized moderation, elegance, and clarity over provocation or radicalism. Adelaide, even in its early decades, did not suffer from a lack of infrastructure. Its challenge was always vitality.

Architecture as Cultural Performance

Perhaps no medium revealed the cultural ambitions of 19th-century Adelaide more clearly than architecture. From the earliest government buildings to the great sandstone facades of North Terrace, Adelaide used architecture to signal its seriousness, its Britishness, and its ideals.

The Public Buildings Committee, formed in the 1850s, directed significant funds toward constructing a city that looked established. Parliament House, the Supreme Court, the General Post Office—all these projects were designed to evoke London rather than the frontier. Their materials—imported stone, iron balustrades, clocktowers—were deliberately European, even when the local climate rendered them impractical.

Churches, too, played a major role. Adelaide was founded as a religiously tolerant colony, and its early skyline was dominated not by cathedrals but by a diversity of steeples and domes. This pluralism of design contributed to a surprising stylistic range: Gothic Revival sat beside Neoclassical, while smaller chapels employed local materials and modest decoration. The presence of skilled German artisans and architects, especially in the Barossa and Adelaide Hills, added a distinctive Northern European flavour to some structures.

Residential architecture also became a subtle field of aesthetic expression. The single-storey villas of North Adelaide, with their lace ironwork and symmetrical facades, became visual shorthand for propriety and taste. Even the simplest terrace homes displayed a careful attention to proportion and ornament.

By the 1880s, Adelaide was a city that looked finished. Its parks were manicured, its avenues wide, its public buildings imposing. But this completeness came at a cost. The dominance of institutional taste—classical, orderly, restrained—left little room for stylistic deviation. Artistic experimentation would struggle to take root in a city so invested in appearances.

Adelaide’s cultural infrastructure emerged early, confidently, and with a strong sense of purpose. Art was not a luxury; it was a civic duty. The institutions built in these decades—formal societies, public libraries, state museums, and architecturally ambitious public buildings—set the tone for generations to follow. But beneath this success lay a paradox: the very strengths that made Adelaide culturally stable also made it, at times, artistically cautious.

Watercolours and Wildflowers: Landscape Painting in the 19th Century

South Australia’s first painters did not have the luxury of tradition. They arrived in a place that resisted their palettes, confused their sense of depth, and offered a natural world that neither obeyed European rules of beauty nor rewarded simple transcription. Yet out of this friction—between foreign eyes and native land—emerged a distinctive school of 19th-century landscape art, shaped not only by what artists saw, but by what they had to unlearn in order to see it.

Capturing the Light of the South

One of the most consistent technical challenges faced by early landscape artists in South Australia was light. The clarity and dryness of the atmosphere, especially in the Adelaide Hills and outback regions, produced a visual experience that differed sharply from the misty depths and tonal gradations of northern European landscapes. Shadows were harder; contrasts sharper. Colour seemed to flatten rather than recede, and long distances could appear oddly compressed.

Many early colonial painters, trained in the English watercolour tradition, struggled to reconcile their inherited techniques with these new visual realities. Subtle glazes, soft washes, and moody skies gave way to bright, sometimes unforgiving plains. It was in watercolour that many found the most responsive medium—light, portable, and capable of capturing fleeting shifts in tone without relying on the heavy impasto or chiaroscuro techniques of oil painting.

The medium also suited the working conditions of colonial artists. Paintings had to be produced quickly, often en plein air, with limited materials and in difficult terrain. Many artists, including surveyors and naturalists, used their sketchbooks as a visual diary—a blend of record-keeping and aesthetic curiosity.

One of the most prolific practitioners of this hybrid form was Martha Berkeley, who arrived in Adelaide in 1837 and produced dozens of precise, modestly scaled watercolours documenting the city’s early architecture and surrounding hills. Though technically limited, her work possesses a documentary charm, recording the incremental growth of Adelaide with the calm of a botanist rather than the drama of a romantic.

By mid-century, however, watercolour had grown from a utilitarian medium into a means of poetic expression. Artists like William Wyatt and F.R. Nixon began to introduce more lyrical effects into their depictions of the South Australian countryside, treating light not only as a technical challenge but as a subject in its own right. Dusk scenes, morning fogs, and golden hilltops became recurring motifs—not just records of place, but meditations on presence.

Hans Heysen and the Eucalyptus Sublime

If one artist transformed the reputation of South Australian landscape painting from a provincial craft into a national idiom, it was Hans Heysen. Born in Hamburg and raised in Adelaide, Heysen embodied the tensions of his adopted land: European in training, Australian in ambition. His great breakthrough came in the first decade of the 20th century, but his career was rooted in 19th-century methods and sensibilities—especially the plein air approach and the use of watercolour for quick atmospheric study.

Heysen’s most iconic subject was the eucalyptus tree. Towering, twisted, and uniquely resistant to European aesthetic conventions, the gum tree had long baffled colonial artists. Its sparse canopy, unpredictable shape, and dry colouration defied the compositional logic of the oak, beech, or pine. Earlier painters either shrunk it into the background or tried to tame its asymmetry. Heysen did the opposite: he elevated the eucalyptus to heroic status.

In large-scale oils such as Droving into the Light (1914–21), and in countless smaller studies of light through bark and branches, Heysen fused the grandeur of European Romanticism with the stark clarity of Australian space. His work was not radical in technique—it remained rooted in academic draftsmanship and tonal realism—but it achieved something few others had: a style that felt native to the place it depicted.

What made Heysen’s gum trees compelling was their specificity. He painted individual trees with the care of a portraitist, noting scars, knots, and shadows with almost forensic attention. And yet he never reduced the landscape to mere botany. His trees glowed with interior light, their branches pulling upward not toward a heavenly sublime but toward heat, sky, and silence.

His home and studio at Hahndorf became a site of pilgrimage for later artists, and his influence can be traced in the practices of both his daughter Nora Heysen and later landscape painters across the country. But it is his rendering of eucalyptus as both symbol and surface—as something simultaneously spiritual and real—that cemented his status.

Pastoral Imagery and the Politics of Beauty

Beyond gum trees and hillsides, South Australian landscape painting in the 19th century carried another, more complicated burden: to make the colony look productive. Art was not merely a personal pursuit; it functioned as advertisement. Pastoral scenes were often idealized depictions of order and fertility, where sheep grazed peacefully, homesteads nestled into tidy valleys, and settlers stood surveying their land with satisfied calm.

This genre—often dismissed as “chocolate box” painting—served a practical and ideological function. Investors in London, reading illustrated reports from the colonies, wanted assurance that their money was well placed. Governments sought to demonstrate the colony’s stability and success. And settlers themselves looked for visual confirmation that their hardship had meaning.

Three visual tropes dominated:

- The cleared valley, often ringed by low hills, with fields laid out in geometric patches of yellow and green.

- The stockman or drover, typically mounted, gazing into the distance or moving cattle across a dusty plain.

- The weathered homestead, modest but solid, anchored to the land with a few gum trees or windmills nearby.

While these images often suppressed the harsher truths of drought, isolation, and land conflict, they also captured something sincere. Many settlers believed deeply in their task, and their landscapes became not just representations of land but visual assertions of belonging.

Yet beneath the surface of these paintings ran a kind of disquiet. The land was beautiful, but it was also unfamiliar, vast, and slow to yield. The harmony depicted in many pastoral scenes was hard-won, and artists knew it. In works by Louis Tannert or John A. Upton, one sometimes sees a creeping loneliness—a tree leaning too far, a sky too pale, a foreground too empty. These hints at emotional dissonance are often subtle, but they disrupt the surface cheerfulness of the genre.

There were also silent absences. Aboriginal presence was largely excluded from these images, not only in figure but in form. The land was portrayed as passive, awaiting cultivation, its spiritual and historical dimensions flattened. That absence, though rarely acknowledged by the artists themselves, is one of the defining features of the period’s visual language.

By the end of the 19th century, landscape painting in South Australia had become both a technical accomplishment and a cultural mirror. It recorded ambition, sentiment, optimism, and erasure—layered in pigment and shadow. The best of these works, especially those by Heysen and his peers, did more than reproduce scenery. They gave visual form to a slow process of acclimatization, in which artists began, cautiously, to see the land on its own terms.

The Garden City and Aesthetic Control

Adelaide is not only a planned city; it is a planted one. From its inception, the city was envisioned as a place of order and ornament—where streets would meet at right angles, and avenues would be softened by trees. It was not simply a functional settlement but a statement about how civilization should look. That vision carried aesthetic consequences that continue to shape the city’s art, public life, and environmental imagination.

Designing Adelaide’s Urban Greenery

The plan devised by Colonel William Light in 1837 did more than define Adelaide’s grid; it established the template for a city enclosed by public parklands. This green belt—unique among Australian capitals—was not a decorative afterthought but an integral part of the city’s original design. Its purpose was not only recreational but ideological: to demonstrate that urban development could coexist with nature, and that public space was a civic right rather than a luxury.

From the earliest decades, municipal authorities took their role as stewards of this vision seriously. The planting of trees along North Terrace, King William Street, and the squares of the city was conducted with deliberation and ceremony. Elm, plane, and pepper trees—many of them non-native—were selected not for ecological suitability but for visual consistency with British models of urban greenery.

Gardening, landscaping, and tree-planting thus became forms of civic participation. Schoolchildren were often enlisted to plant commemorative trees; city councils appointed arborists and oversaw detailed reports on the health of the urban canopy. These acts, however mundane, constituted a kind of public performance—a continuous aesthetic shaping of the city in line with its founding ideal.

The visual consequences were striking. By the late 19th century, Adelaide was already being referred to as “The Garden City,” not as a utopian metaphor but as an observable fact. Its regularity, symmetry, and green orderliness lent themselves to representation in lithographs, postcards, and panoramas. Local artists increasingly turned their attention not only to wilderness but to this new, human-shaped environment, where gum trees gave way to flower beds and rotundas.

Yet beneath the beauty, there was calculation. The parklands, while ostensibly democratic, also functioned as buffers—keeping the working-class suburbs physically and symbolically outside the central grid. Green space became a tool for both inclusion and exclusion, and its aesthetic appeal masked more complex social boundaries.

Botanic Illustration and Scientific Art

Just as the city’s trees were chosen and planted with a sense of symbolic order, so too were its flowers, herbs, and shrubs recorded with scientific precision. The Adelaide Botanic Garden, formally established in 1855 under the directorship of George Francis, quickly became a centre not only for horticulture but for artistic production.

Botanical illustration thrived in this setting, drawing on the talents of both trained artists and skilled amateurs. The genre required a combination of accuracy and elegance—a delicate balance between diagram and image. Watercolour remained the preferred medium, and many of these works were intended not for gallery walls but for journals, seed catalogues, and the archives of scientific institutions.

Rosa Fiveash, one of the most accomplished botanical artists in South Australian history, exemplified this hybrid role. Trained at the Adelaide School of Design and working closely with botanist Richard Schomburgk, she produced hundreds of detailed renderings of native plants, including intricate depictions of the Sturt’s desert pea and the South Australian blue gum. Her illustrations were not decorative flourishes; they were scientific tools. Yet their aesthetic power was undeniable.

In these works, the discipline of classification did not cancel out beauty. The way a petal curled, the way colour deepened near the base of a leaf—these were not merely descriptive details, but expressions of care. The best botanical artists imbued their work with quiet authority, conveying the dignity of the plants themselves without imposing sentimentality.

Adelaide’s embrace of this genre also reveals something deeper about its cultural identity: a commitment to order, clarity, and restraint. In contrast to the expressive turbulence of Sydney’s art scene or the grandiosity of Melbourne, Adelaide’s visual culture often privileged control. Even in the depiction of wild plants, there was an insistence on structure.

City Planning as Artistic Endeavour

By the early 20th century, Adelaide’s urban aesthetic had become a matter not just of tradition but of ideology. The Garden City movement, emerging in Britain and spreading across the colonies, gave formal backing to ideas that Adelaide had long practiced. The belief that a city should be green, walkable, and zoned for moral improvement found fertile ground in a place already designed for it.

The work of Charles Reade, appointed South Australia’s first official Town Planner in 1916, illustrates this alignment. Reade advocated for controlled growth, the preservation of parklands, and the integration of beauty into infrastructure. He saw the city itself as a kind of civic artwork—one that required maintenance, balance, and vision. His influence extended beyond Adelaide to regional planning in Whyalla and Port Augusta, but his deepest impact was in reinforcing the aesthetic ethos of the capital.

Public housing developments in the interwar period, such as those built by the South Australian Housing Trust, often followed these principles. Streets were curved rather than gridded, homes were set back from the street, and green verges were maintained. While modest in architectural ambition, these developments reflected a belief that beauty and livability were linked.

Art entered this process in subtle ways. Mural decoration in schools, mosaic signage, and the inclusion of small sculpture in civic parks all reflected the idea that public life should have visual interest. Artists were occasionally commissioned to work alongside architects or landscape designers, though often on the periphery. More often, aesthetic values were embedded in materials and proportions rather than overt ornament.

There is a quiet continuity in Adelaide’s planning history—a refusal to abandon the original vision of Light’s design, even as the city modernized. Unlike other capitals, which obliterated their colonial cores in pursuit of scale or spectacle, Adelaide held fast to its proportions. This resistance to rupture may have limited architectural daring, but it preserved a visual coherence rare among Australian cities.

Adelaide’s identity as a garden city is not just a matter of landscaping. It is an aesthetic position: a belief in the possibility of beauty through order, and in the social value of controlled design. From parklands to botanical drawings, from school murals to tree-lined streets, the city has been shaped by a quiet determination to look composed. That composure, while often praised, also hints at constraint—a recurring theme in Adelaide’s visual history.

The Shadow of Europe: Modernism Arrives Late

Modernism did not erupt in Adelaide; it seeped in, quietly, and often under protest. While the aesthetic revolutions of Paris, Berlin, and even Sydney were reshaping the vocabulary of Western art in the early 20th century, South Australia maintained a polite resistance. It was not hostile to change, exactly, but cautious—and institutionally conservative. Yet the delay proved fruitful. When modernism finally gained traction in Adelaide, it did so with a peculiar energy: half-imported, half-invented, and fully entangled in the city’s longing to be seen.

Marginal Modernity and Peripheral Experimentation

Geographic isolation often breeds innovation, but not always in predictable ways. Adelaide’s distance from Europe—and even from the cultural hubs of eastern Australia—produced a sense of artistic marginality. For some, this was a frustration. For others, it was permission.

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, Adelaide’s mainstream art institutions clung to the traditions of academic realism and romanticised landscape. The Art Gallery of South Australia’s acquisitions reflected this preference, favouring technically skilled but stylistically conservative works. Teachers at the South Australian School of Art, while competent and sincere, often remained firmly within the framework of British draughtsmanship and tonal rendering.

Into this restrained atmosphere came a small but decisive wave of artists and writers drawn to the experimental spirit of modernism. Some were self-taught; others had studied abroad. Their exposure to Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism, and Symbolism left them unsatisfied with the genteel images still celebrated in local exhibitions.

One important early figure was Dorrit Black. Having studied in London and at André Lhote’s academy in Paris, she returned to Adelaide in 1935 determined to promote modern art. Black’s work—especially her linocuts and geometric landscapes—shows a direct engagement with European formalism, translated into a distinctly Australian visual idiom. Her 1940 painting The Bridge reimagines the Sydney Harbour Bridge not as an engineering feat but as a flattened interplay of form, shadow, and rhythm. She founded the Modern Art Centre in Adelaide, the first of its kind in the country, offering a rare space for progressive thought in an otherwise cautious environment.

Despite these efforts, Adelaide remained ambivalent. Critics and curators were often dismissive. The broader public, shaped by decades of pastoral romanticism and British refinement, found the new idioms jarring or opaque. Still, Black and her circle—including fellow modernists Mary Packer Harris, Ruth Tuck, and Shirley Adams—persisted. Their exhibitions were modest, but their influence outpaced their visibility.

Adelaide’s delayed modernism was neither a copy of European movements nor a rejection of them. It was something more tentative: a negotiation between imported style and local sensibility. And in that negotiation, something quietly original began to form.

The Angry Penguins and the Quest for Relevance

If Adelaide’s painters hesitated to provoke, its writers did not. The most famous eruption of modernism in South Australian culture came not from easels or sculpture but from the pages of a magazine. Angry Penguins, first published in 1940 by Max Harris, a precocious poet and critic, became a lightning rod for avant-garde ambition.

Though the magazine began in Melbourne, its energy, funding, and intellectual centre quickly shifted to Adelaide, thanks to Harris and the wealthy arts patron Sunday Reed. The title itself—a nonsensical phrase drawn from surrealist impulse—signaled its attitude: irreverent, experimental, and unapologetically modern.

Angry Penguins published poetry, essays, and visual art that embraced symbolism, abstraction, and emotional extremity. It championed figures like Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd, whose work defied narrative realism in favour of psychological intensity. It also courted controversy, most famously in the Ern Malley hoax of 1944, in which two conservative writers submitted a suite of absurdist poems under a fictional name to expose the pretensions of modernist criticism. Harris, taken in by the ruse, published the poems with great fanfare. The scandal that followed tarnished his reputation but also cemented Angry Penguins in Australian cultural history as a site of both brilliance and vulnerability.

For Adelaide, the episode was double-edged. On one hand, it confirmed the city’s role as a crucible for modernist thought, even if it lacked institutional support. On the other, it exposed the fragility of that scene—its dependence on a few charismatic figures, its distance from broader public understanding, and its tendency toward aesthetic insularity.

Still, the legacy of Angry Penguins endures. It linked Adelaide to international currents in surrealism, psychoanalysis, and abstraction. And it opened space for visual artists who were beginning to test the limits of representation. Painters like Jeffrey Smart, who would later relocate to Europe, began their careers in this atmosphere of tentative modernism, nourished by literature as much as by visual precedent.

Formal Rebellion and Institutional Discomfort

By the 1950s and 60s, modernism had lost its shock value in the international art world. But in Adelaide, it still retained the power to unsettle. Public institutions lagged behind private experimentation. The Art Gallery of South Australia, though slowly acquiring more contemporary works, continued to present modern art within cautious frames. When it did display abstraction or expressionism, it was often buffered by explanatory text or downplayed in curatorial emphasis.

Yet outside the gallery system, artists were pushing boundaries. The Contemporary Art Society, founded in 1942 with a South Australian branch soon following, became a key platform for experimental work. Its exhibitions included non-objective painting, assemblage, and proto-conceptual art. Many participants—such as Sydney Ball and Ian Fairweather—would go on to shape the national conversation about form, colour, and materiality.

These years also saw the rise of modernist architecture in Adelaide, particularly in university buildings, civic centres, and private homes. Architects like Jack McConnell and John Overall brought internationalist style to the city’s skyline, embracing glass, concrete, and steel as symbols of postwar optimism. Though architecture is often treated separately from visual art, the interplay was significant: both fields were engaged in questions of abstraction, scale, and the relation of form to function.

There was resistance, of course. Modernist work—whether on canvas or in concrete—was frequently described as cold, foreign, or unnecessary. Letters to editors lamented the decline of “real painting.” Critics questioned the value of “meaningless shapes.” Adelaide’s institutions, still shaped by 19th-century ideals of beauty and craftsmanship, hesitated to endorse what they could not categorise.

Yet the ground was shifting. By the late 1960s, students at the South Australian School of Art were engaging with pop, minimalism, and conceptualism. National and international exhibitions began to feature Adelaide artists who had outgrown their provincial label. And the city’s cultural leaders were slowly learning that artistic innovation could be framed not as a threat to order, but as a sign of maturity.

Adelaide’s modernism was not loud. It did not explode in manifestos or sweep through institutions with revolutionary speed. It arrived through back doors and private studios, through student magazines and side-room exhibitions. But in its hesitations, it found a voice. The long delay, the slowness to accept, and the resistance to change all produced a form of modernism uniquely shaped by distance—not from the world, but from consensus.

Women in the Frame: Adelaide’s Overlooked Artists and Their Legacy

In Adelaide’s early cultural record, women are everywhere—and almost nowhere. They populate exhibition catalogues, art school rosters, and the margins of institutional histories. Their work, often praised in its time, was quietly dismissed in the decades that followed. The exclusion was not always overt. It was administrative, structural, and habitual: a system that defined seriousness in terms men had already set. And yet, from parlour sketchbooks to national portraiture, women artists in Adelaide laid a foundation of aesthetic strength, subtle rebellion, and hard-earned recognition.

Portraits, Parlor Arts, and the Canon’s Blind Spots

For much of the 19th century, women in Adelaide had access to training, materials, and exhibition spaces—but not necessarily to careers. Art was encouraged as a refinement, not a profession. Drawing and watercolour were taught in girls’ schools and finishing colleges as part of a civilised upbringing. These works—floral studies, domestic scenes, careful landscapes—were technically competent and sometimes brilliant, but rarely acquired by galleries or reviewed in the press.

This boundary between amateur and professional was not simply about skill; it was enforced through institutions. The South Australian Society of Arts allowed women to exhibit but rarely awarded them prizes. Art schools accepted women students but disproportionately hired male instructors. Criticism, when it came, often focused on charm or delicacy rather than formal innovation.

Despite these limitations, a generation of women artists emerged with discipline and ambition. Rosa Fiveash, best known for her botanical illustrations, produced works of remarkable precision and elegance. Her training at the Adelaide School of Design under H. P. Gill gave her a grounding in academic technique, which she applied with scientific clarity to South Australia’s native flora. While rarely described as a “painter” in the broader sense, Fiveash’s contributions to both art and natural science were significant—and unusually durable.

Equally important, though often overlooked, were Adelaide’s many portraitists and miniaturists. Women such as Margaret Glover and Maude Priest exhibited regularly at local shows and took private commissions that circulated widely in middle-class homes. Their work documented a generation of faces—children, wives, clergy, soldiers—that rarely made it into official portraiture. In doing so, they created a parallel visual archive of the colony’s social history.

The blind spot wasn’t just exclusion from collections. It was the habit of treating women’s art as ephemera—as delicate things that faded, rather than works that endured. Even today, many of these pieces survive only in family holdings or uncatalogued archives, unscanned, unsigned, and misattributed.

Stella Bowen and the Tension of Exile

The most prominent South Australian-born woman artist of the early 20th century remains Stella Bowen—a painter whose fame came not in Adelaide, but in Europe. Born in 1893 and educated at Adelaide High School and the University of Adelaide, Bowen left for London in 1914 and immersed herself in the expatriate literary scene. She lived with the writer Ford Madox Ford, socialised with the Bloomsbury Group, and pursued painting with stubborn purpose.

Bowen’s self-portraits and domestic interiors are technically modest but emotionally intense. Her style—lean, economical, slightly flattened—owes something to the post-Impressionist mood of her circle, but her subject matter remained grounded in daily life. She painted friends at dinner tables, her daughter sleeping, herself weary in a mirror. These were not glamorous images, but neither were they private confessions. They were records of attention: small truths rendered without performance.

In 1944, Bowen was appointed an official war artist for the Australian government. Her paintings of airmen in England, bombed-out buildings, and military dormitories are some of the most quietly devastating images of the war. Unlike the triumphalism of many male war artists, Bowen’s work conveys exhaustion, boredom, and the emotional cost of service. Her portrait of Flight Lieutenant John Dyer, seated and looking away, captures the dignity of disillusionment with rare clarity.

Yet despite these achievements, Bowen remained on the margins of Australian art history for decades. Her expatriate status, modest production, and refusal to conform to either abstraction or heroic realism left her without a critical home. It was not until the 1980s, with a retrospective at the Art Gallery of South Australia, that her work was reappraised in earnest.

What Bowen’s career makes clear is the tension many Adelaide women artists faced between presence and recognition. To succeed often meant to leave. To remain was to risk invisibility.

New Appraisals and a Slow-Moving Revolution

The marginalisation of women artists in Adelaide was not eternal, but it was persistent. It lingered well into the mid-20th century, even as more women graduated from art schools, held exhibitions, and taught in university departments. Institutional change came slowly—and often under pressure.

By the 1970s and 80s, feminist scholars and curators began to challenge the omissions of the canon. Exhibitions such as Australian Women Artists: One Hundred Years 1840–1940, first staged in Melbourne and later adapted for South Australian audiences, drew attention to the long record of ignored or undervalued work. Adelaide artists like Jacqueline Hick, whose brooding figurative paintings explored urban loneliness and psychological strain, were re-evaluated not as curiosities but as central figures in the national story.

More recently, the Art Gallery of South Australia and regional institutions have begun to acquire and display works by lesser-known women artists of the past, alongside contemporary figures such as Catherine Truman (jewellery and installation), Fiona Hall (mixed media and sculpture), and Hossein Valamanesh’s collaborator Angela Valamanesh. These acquisitions, while still piecemeal, mark a shift from tokenism to serious engagement.

This reappraisal has been driven in part by archival work—digging into family collections, old exhibition records, and forgotten portfolios—and in part by younger artists themselves. Many Adelaide-based women artists in the 21st century have made a point of reclaiming their predecessors, not only in name but in form. Echoes of early botanical illustration, needlework, and domestic scale appear in new media practices, site-specific installations, and hybrid craft-art experiments.

The slow revolution of recognition is not without cost. For many, rediscovery comes decades too late. And there remains the risk of historicising women artists as exceptions—singular figures rather than part of a broader tradition.

Adelaide’s women artists were never absent. They were present, producing, teaching, exhibiting, and documenting the world around them. What they lacked was not agency but acknowledgment. As institutions begin to correct the record, the art remains—quiet, unclaimed, and waiting to be seen not as marginal, but essential.

Post-War Expansion and the Creation of the Art Gallery of South Australia’s Identity

In the years following World War II, the Art Gallery of South Australia transformed from a quiet provincial repository into one of the most distinctive and intellectually ambitious cultural institutions in the country. It did so not through wealth or scale, but through conviction—and a carefully cultivated sense of identity. While other galleries chased international prestige or leaned heavily on blockbuster exhibitions, Adelaide’s leading art institution turned inward, constructing a collection and philosophy that drew strength from coherence, depth, and, at times, deliberate eccentricity.

Max Harris, Patronage, and Provocation

No individual shaped Adelaide’s post-war artistic climate more idiosyncratically than Max Harris. A poet, publisher, critic, and cultural provocateur, Harris straddled the worlds of literature, journalism, and visual art with theatrical confidence. Having made his name as the enfant terrible of Angry Penguins, he spent the postwar decades not in bohemian exile but at the centre of Adelaide’s commercial and cultural life—writing for newspapers, running the Mary Martin Bookshop, and advising both private collectors and public institutions.

Harris was not a curator, but his influence on acquisitions, reputations, and public taste was substantial. He championed artists others ignored: surrealists, symbolists, and late romantics. He advocated for modernism not in its internationalist, abstract form, but in its psychologically charged, often figurative incarnations. His taste ran toward the enigmatic and the lyrical—qualities that began to inform the gallery’s character under directors who respected, if not always followed, his instincts.

This period also marked the rise of Adelaide’s private collecting class—figures like Mary Martin herself, Ann and Gordon Samstag, and the Barr Smith family—who often acted as intermediaries between artists and institutions. Their purchases, donations, and advocacy allowed the gallery to develop areas of strength without state dependence. Though modest in budget, the Art Gallery of South Australia became unusually rich in certain areas: British Symbolism, Australian Surrealism, and, later, colonial portraiture and decorative arts.

Harris understood that a gallery’s power lay not in its size, but in its editorial voice. He treated the gallery as a cultural argument: a place to persuade, provoke, and unsettle, rather than merely display. His presence was sometimes divisive, but always catalytic.

Acquisitions, Ambitions, and the Building of a Collection

Under the directorship of Daniel Thomas in the 1970s and early 80s, the gallery’s collection strategy took a more structured and scholarly turn. Thomas, trained as an art historian and steeped in the principles of connoisseurship and archival research, brought a new seriousness to both curation and interpretation. His emphasis was on quality over novelty, coherence over fashion. He sought to make the gallery not just a mirror of current taste, but a repository of layered history.

One of the defining features of the gallery’s development during this period was its commitment to filling gaps. Rather than pursuing only contemporary work or large-scale international names, the gallery focused on assembling a comprehensive and contextualised history of Australian art. It built strength in overlooked areas: early colonial painting, 19th-century sculpture, women’s decorative arts, and mid-century figurative works that had fallen out of critical favour.

This approach had three advantages:

- It gave Adelaide a unique institutional voice, distinct from the internationalist ambitions of Sydney or the scale-obsessed collecting of Melbourne.

- It allowed the gallery to develop excellence in areas neglected by others, creating depth rather than breadth.

- It fostered a culture of interpretation—of writing, scholarship, and exhibition-making—that treated the collection as an ongoing argument rather than a static display.

Significant acquisitions during this period included works by Clarice Beckett, Rupert Bunny, and Grace Cossington Smith—artists whose reputations had suffered from critical neglect but whose re-evaluation would place the gallery ahead of national trends. The gallery also began acquiring non-European works with greater seriousness, including Asian textiles, Islamic metalwork, and eventually a stronger Indigenous Australian collection.

The result was a collection defined not by consensus, but by choice. It rewarded the attentive viewer, the historically curious, the stylistically open-minded. The Art Gallery of South Australia became not the largest, but perhaps the most narratively rich collection in the country.

The Gallery as a Cultural Mirror

Institutional identity is never fixed, and the gallery’s trajectory in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has continued to shift—at times sharply. Under successive directors, including Ron Radford, Nick Mitzevich, and currently Rhana Devenport, the gallery has navigated a changing landscape of funding models, curatorial fashion, and public expectation.

One of the most visible changes in recent decades has been the gallery’s embrace of spectacle—particularly through the success of the Biennial of Australian Art (now The Adelaide Biennial), a regular national exhibition that draws contemporary artists into thematic group shows across the gallery’s entire footprint. These exhibitions have pushed the institution into more experimental territory, showcasing installation, digital media, and performance alongside painting and sculpture. They have also brought new audiences into the gallery—curious, younger, and less attached to traditional hierarchies.

Yet the gallery has retained its sense of tone. Even its most contemporary exhibitions tend to be organised with clarity and restraint. There is less theatrical chaos than in comparable events in Sydney or Venice. The lighting is elegant. The wall texts are literate. The works are allowed to breathe.

A particularly telling example of the gallery’s recent self-awareness is its curatorial rehangs. Rather than adopting the chronological or nationalist models common in encyclopaedic collections, the gallery has increasingly turned to thematic and aesthetic groupings. In doing so, it acknowledges the biases of its own history—gendered, Eurocentric, and shaped by donor influence—while also resisting the shallowness of fashion-led curation. It presents itself not as a neutral space, but as a constructed one.

Perhaps most emblematic of the gallery’s dual identity—traditional and forward-looking—is its handling of decorative arts. Where many major galleries marginalise furniture, textiles, and ceramics, Adelaide continues to treat them as central. Entire rooms are dedicated to design history, and objects are often presented with the same care and prominence as paintings. This approach reflects not only the city’s collecting history but also its cultural temperament: thoughtful, composed, and slow to discard the past.

The Art Gallery of South Australia is not a passive container. It is an actor in the city’s artistic life—sometimes a provocateur, sometimes a caretaker, but always a participant. Its evolution from colonial showcase to modern cultural engine reflects Adelaide’s broader story: a city that values coherence over noise, and continuity over fashion, but which—when it chooses—can still surprise.

Kaurna Artists and the South Australian Landscape Tradition

The land on which Adelaide stands is Kaurna country. This is not a footnote to the city’s history, but its origin. For generations, that origin was overwritten—first by colonial maps and municipal grids, then by the art institutions that emerged around them. Only in recent decades has Adelaide begun to reckon with the visual traditions, cultural knowledge, and living artistic practices of the Kaurna people and other Aboriginal artists whose work has reshaped South Australian art. This process has not been tidy. It has unfolded across protests and exhibitions, political shifts and personal stories, in a city where landscape was once pictured without its people.

Art as Inheritance and Adaptation

Traditional Kaurna visual culture—like that of many Aboriginal nations—was expressed in forms not historically recognised by Western institutions as “art.” Body painting, carved objects, woven fibre works, and ephemeral designs in sand or ash were embedded in ceremony, law, and daily life. These forms, though not collected or preserved by early settlers, carried meaning across generations: they marked place, encoded knowledge, and maintained spiritual ties to specific sites, flora, and fauna.

The disruption of this continuity by the colonisation of South Australia was immediate and violent. Dispossession, language loss, and the forced displacement of Kaurna people into missions and fringe settlements severed many forms of traditional practice. Yet even in this rupture, adaptation began. Visual expression did not vanish—it transformed. Materials changed, audiences shifted, and new techniques entered the repertoire, often combining traditional references with modern media.

In the late 20th century, a revival of Kaurna cultural practices gained momentum through the work of artists, linguists, and elders committed to restoring knowledge and asserting presence. Visual art became one of the most powerful vehicles for this process—not only as heritage, but as invention. Artists like Jacob Stengle, whose finely rendered paintings depict both historical trauma and community life, represent a generation working to reconnect fragmented stories and reassert Kaurna sovereignty through image.

Others, including contemporary printmakers and sculptors, have drawn on inherited motifs—lines of movement, seasonal symbols, ancestral beings—and translated them into new forms. The use of ochre, wood, and natural fibres continues, but so too does the adoption of acrylics, photography, and video. In this way, Kaurna art today is not a static revival, but a live and evolving language.

From Local Practice to Institutional Display

For most of the 20th century, South Australian institutions treated Aboriginal art as ethnography rather than aesthetic achievement. Collections focused on tools, implements, and ceremonial items, often acquired without consent and displayed without attribution. The Art Gallery of South Australia, though more progressive than some peers, was slow to incorporate Aboriginal artists into its contemporary holdings or major exhibitions.

Change began in the 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s, spurred by broader national conversations around land rights, cultural ownership, and Indigenous visibility. Exhibitions like Tjukurpa Pulkatjara (2003) and Desert Country (2010), both curated at AGSA, began to reposition Aboriginal art not as peripheral but as central to Australian visual culture. These shows gave serious space to artists from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands, but they also made room for voices closer to Adelaide—Kaurna, Ngarrindjeri, and Narrunga artists whose work had long been obscured by the dominance of desert painting in the Aboriginal art market.

One pivotal figure in this shift has been Karl Telfer, a Kaurna cultural leader and artist whose installations, performances, and public works emphasize both the depth of ancestral knowledge and its contemporary urgency. His collaborations with institutions—including museum reinterpretations and site-specific projects—have helped recalibrate how place, identity, and history are understood in Adelaide’s cultural sphere.

The rise of dedicated Aboriginal curatorial roles within AGSA and other institutions has also marked a structural change. Curators such as Nici Cumpston have reshaped exhibition priorities, collection strategies, and interpretive frameworks, placing Aboriginal voices at the centre rather than the edge. This curatorial presence ensures that Aboriginal art is not merely shown, but contextualised on its own terms.

Still, the relationship between institutional display and community practice remains delicate. The gallery wall is not always a natural home for works rooted in story, ceremony, or activism. Many artists continue to produce work outside of commercial or institutional frameworks, sharing their art in community halls, schools, and health centres—spaces that do not confer prestige but allow for continuity.

Cross-Territory Dialogue in South Australian Collections

South Australia’s Aboriginal art is not confined to Kaurna country. The state encompasses vast and culturally diverse lands, from the coastal communities of the south-east to the red deserts of the north and the salt lakes of the interior. This geographic and cultural range is reflected in the collections of South Australia’s institutions, which hold major works from the APY lands, the Western Desert, and Arnhem Land alongside locally produced art.

The interaction between these traditions—each with distinct symbols, languages, and styles—has created a layered and sometimes contradictory visual record. Adelaide-based galleries and art centres have had to navigate this complexity, often balancing market demand for desert dot paintings with commitments to support local community artists whose work does not conform to commercial expectations.

One of the most successful frameworks for this dialogue has been collaborative exhibitions that bring together multiple regional voices. Shows like Kulata Tjuta (2017), which presented contemporary sculpture and installation from the APY lands in a high-concept, politically charged format, offered a model for how South Australian art institutions can present Aboriginal art without flattening its differences.

Equally important are artist-run spaces and community workshops, such as those supported by Ku Arts and Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute. These platforms allow artists to experiment, teach, and connect across territory lines, while also challenging the dominance of curatorial authority. They remind audiences that Aboriginal art is not a genre but a plurality of practices—sometimes in conversation, sometimes in tension, and always grounded in specific relationships to place.

The presence of Kaurna artists within this broader ecology is increasingly visible. Public art projects along the River Torrens / Karrawirra Parri, installations at the Adelaide Festival Centre, and collaborations with schools and councils have brought Kaurna motifs, language, and stories back into the city’s visual field—not as decoration, but as claim.

Adelaide’s history of landscape art begins with absence: a land rendered empty, its original custodians unacknowledged. The emergence of Kaurna artists and their peers across South Australia is not a correction—it is a return. Through painting, sculpture, performance, and installation, they have re-entered the frame, not as subjects of someone else’s gaze, but as makers, speakers, and teachers. The land looks different now. It always did.

The Adelaide Festival and the Art of Performance

In Adelaide, performance art did not grow in the shadow of the visual arts—it burst into view, sometimes literally, on the city’s streets, lawns, and stages. With the founding of the Adelaide Festival in 1960, the city became host to an unprecedented experiment: a state-funded, publicly visible platform for avant-garde theatre, music, dance, and increasingly, visual art that refused to stay inside gallery walls. It was not just a festival of entertainment, but an annual opportunity for the city to test its boundaries, aesthetically and socially. And while Adelaide remained cautious in many areas of artistic life, the Festival became a space where caution could be temporarily suspended.

Avant-Garde Publicness in a Conservative City

The inaugural Adelaide Festival of Arts was both elite and populist, ambitious and mannered. Modelled in part on Edinburgh’s festival model, it brought international acts to South Australian stages and introduced audiences to forms of performance they had rarely encountered before. European theatre troupes, modernist orchestras, contemporary dance companies, and experimental filmmakers arrived in waves. From the start, there was tension: a festival conceived by a largely conservative establishment began to showcase artists whose work was deliberately provocative.

Yet this was part of its power. Adelaide, a city known for order and restraint, found itself redefined—if only briefly—each festival season. Public life was punctuated by moments of dissonance: modern dance on church lawns, abstract film projected onto civic buildings, site-specific performance that treated the city as a stage. The Festival invited not only viewing, but participation.

By the 1970s, visual artists had begun to claim more space within this performance-oriented structure. Installation, video, and multimedia works appeared in parallel programs. Outdoor sculpture, light displays, and process-based art events blurred the lines between stage and gallery, between audience and participant.

One pivotal example came in 1972, when artist Aleks Danko presented his satirical performance installations critiquing nationalism and cultural mythmaking. Danko, born in Adelaide to Ukrainian parents, embodied the hybrid nature of the festival’s expanding identity: formally educated, politically sharp, and deeply attuned to the absurdity of civic ritual. His works, which combined deadpan humour with sculptural craft, set a tone for the local avant-garde that followed.

The Festival thus became a testing ground not only for imported excellence but for local disruption. Artists who might otherwise be marginalised in the city’s conservative galleries found temporary visibility—and sometimes lasting influence—through festival commissions and side programs.

Tensions Between Art and Audience

The Adelaide Festival’s greatest success has also been its greatest strain: it made challenging art public. Unlike gallery exhibitions or niche performances that attract self-selecting audiences, the Festival placed experimental work in the civic sphere, where it had to face people who had not asked for it.

This produced memorable frictions. In 1974, a piece by Sydney-based performance artist Mike Parr—whose work often included bodily endurance and confrontation—was met with confusion and protest. Parr’s piece involved silent presence, altered movement, and self-imposed restraint: subtle to the point of invisibility. Many viewers dismissed it as nonsense. Others saw it as threatening. Parr would later note that “Adelaide was not ready for silence.”

And yet, each conflict expanded the city’s capacity to absorb complexity. The Festival’s public profile made it impossible to ignore contemporary art’s more difficult edges. Even conservative critics were forced to engage, to argue, to attend. The Festival institutionalised dissent—not politically, but culturally.

Audience discomfort was not always about content. Sometimes it was about context. When performance art entered shopping malls, train stations, or civic parks, it altered the terms of engagement. The usual cues—gallery walls, opening speeches, white cubes—were gone. Artists had to negotiate space, logistics, and unpredictability. Viewers had to decide whether they were part of the performance or merely in the way.

This unpredictability produced some of the Festival’s most electric moments:

- The appearance of large-scale kinetic sculpture in Rundle Mall during peak shopping hours.

- Interactive light environments on the steps of Parliament House.

- Temporary structures that invited occupation, sleep, and vandalism.

These moments were not just artistic interventions. They were urban experiments in attention and behaviour.

Ephemera, Installations, and the Festival’s Visual Turn

By the 1990s, the Adelaide Festival had begun to shift more decisively toward visual art—not by sidelining performance, but by expanding what “performance” could mean. Installations became more ambitious, often merging sculpture, sound, light, and video into immersive environments. The temporary nature of these works—built to last days or weeks—became a defining aesthetic feature.

The 2002 Festival, directed by Peter Sellars, marked a turning point. Its heavy emphasis on global politics, Indigenous sovereignty, and multimedia installations received mixed reviews but introduced a new scale of ambition. Works such as William Kentridge’s animated video installations and the collaborative project A Drone Opera brought together music, image, surveillance, and spatial choreography in ways that redefined the visual vocabulary of the Festival.

Meanwhile, local artists continued to push boundaries. Adelaide-based artist Stelarc presented performances using robotic prosthetics and body suspension, confronting the limits of flesh and technology. His work, though controversial, aligned with the Festival’s increasing interest in transdisciplinary practice—where art, science, and philosophy collided.

The Festival’s embrace of ephemerality also challenged collecting institutions. These works, by nature temporary, left no object to acquire. Documentation became key: video recordings, artist interviews, architectural models. The gallery shifted from a site of preservation to a site of memory. Adelaide’s archives swelled with performance artefacts—programs, photos, sketches—creating a history built on what had vanished.

This raised questions still being negotiated: How does a city remember art that was meant to disappear? How does it measure impact without lasting form?

The Adelaide Festival made performance visible—not just to the elite, but to the city. It brought art into public space, sometimes gently, sometimes with disruption, but always with consequence. What began as a civic celebration became a recurring challenge: to see differently, to risk confusion, and to experience art not as passive viewing, but as encounter. In a city shaped by order, the Festival made room for rupture.

Education and Experimentation: The Art School as Incubator

Adelaide’s reputation as a city of formalism and order has always sat uneasily beside the restless, often anarchic energy of its art school culture. For more than a century, the South Australian School of Art and its institutional successors have functioned as laboratories of technique, rebellion, and identity formation. It is here—in classrooms, studios, and pub conversations—that the city’s most enduring artistic debates have been rehearsed, overturned, and occasionally buried. The art school has not simply trained artists; it has trained Adelaide to tolerate its own capacity for invention.

The South Australian School of Art and Its Legacy

Founded in 1856 as the School of Design under Charles Hill, the South Australian School of Art is one of the oldest such institutions in the country. From the beginning, it was grounded in a British academic model: drawing from casts, mastering perspective, and adhering to the slow climb from technical proficiency to compositional freedom. For much of its first century, the school’s curriculum was conservative but serious. Its graduates went on to teach, illustrate, exhibit, and participate in the slow construction of a provincial aesthetic culture.

By the mid-20th century, however, pressures for reform began to mount. The rise of modernism and the increasing professionalisation of art education brought international currents into tension with local expectations. Students wanted more than still life and anatomy; they wanted theory, materials, and access to contemporary discourse. Teachers were often caught between fidelity to tradition and an unease with abstraction or experimentation.

The 1960s and 70s saw a decisive shift. Under the influence of visiting lecturers, international residencies, and internal student movements, the School of Art began to embrace newer forms: printmaking, photography, video, and installation. The school became part of the South Australian Institute of Technology (now the University of South Australia), and its pedagogical ambitions widened. It was no longer just a place to learn how to paint—it became a place to learn how to think about art.

Some of Australia’s most influential artists and educators passed through its halls during this period. Sydney Ball, for example, returned from New York in the late 1960s and brought with him the language of colour field abstraction and hard-edge painting. His presence as both practitioner and teacher helped shift the conversation away from figurative traditions and toward materiality, scale, and spatial logic.

Others, like Ann Newmarch, took the school in another direction—toward political art, feminist critique, and community practice. Newmarch, who taught printmaking and founded the Progressive Art Movement, was a forceful presence in Adelaide’s 1970s art scene. Her silkscreens and poster designs tackled social inequality, domestic violence, and cultural erasure with clarity and formal power. She also redefined what an art school could do: not just teach technique, but generate publics.

These divergent paths—abstraction and activism, form and message—have remained in productive tension within Adelaide’s art education institutions. The school has incubated artists who make work for galleries and for protests, for biennials and for nursing homes. That heterogeneity is one of its enduring strengths.

Workshops, Studios, and the Art of Mentorship

Much of what gives an art school its character happens outside the syllabus. It happens in the studio—the shared spaces where materials are tested, failures accumulate, and new forms begin to cohere. Adelaide’s art school tradition has long been shaped by the quality of these spaces, and by the teaching culture that animates them.

Workshops in sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking have been particularly vital. In contrast to theory-heavy departments in some other cities, Adelaide retained a strong emphasis on process and making. This has attracted generations of artists whose work is grounded in material intelligence, including notable ceramicists like Gwyn Hanssen Pigott and furniture makers influenced by the JamFactory’s training programs.

Mentorship has played a critical role in sustaining this culture. Artists who stayed in Adelaide to teach—sometimes despite limited recognition elsewhere—created lines of influence that are traceable through multiple generations. These mentors often offered more than technical advice: they modeled seriousness, patience, and independence. In a city not always quick to celebrate its own, the studio became a sanctuary.

The relationship between teacher and student in Adelaide’s art schools has often been intimate—less hierarchical than elsewhere, and more sustained. It is not unusual to find contemporary artists who still work alongside, or even collaborate with, their former tutors. This continuity has helped Adelaide maintain an identity distinct from the cycles of novelty that characterise larger scenes.

At the same time, the studio has also been a site of contest. Debates over assessment, gender, cultural appropriation, and institutional priorities have played out in critiques and classroom confrontations. But rather than smoothing these over, the best educators have allowed them to become part of the learning. The art school has taught students not only how to make work, but how to live with the work they make.

Failure, Risk, and the Necessity of the Fringe

In Adelaide, the art school has often been the birthplace of failure—and that has been part of its function. Not every student becomes a professional artist. Not every project succeeds. But the school has cultivated a tolerance for risk that extends into the city’s broader culture.

This ethos finds its clearest expression in the Adelaide Fringe, the annual open-access festival that runs alongside the more formally curated Adelaide Festival. Though originally conceived as a space for alternative theatre, the Fringe has become a proving ground for emerging visual artists, many of them art school graduates. Pop-up exhibitions, experimental installations, and ephemeral street art fill warehouses, pubs, and alleyways. The line between student project and professional practice often blurs.

The Fringe offers what the gallery cannot: the chance to fail in public, cheaply, and without lasting consequence. For many artists, this is the real beginning of their career—not the degree, but the moment when their work meets an audience outside the academy.

The spirit of improvisation fostered by the Fringe feeds back into the school itself. Students see their tutors exhibiting. Artists see their peers taking risks. What emerges is a culture of visibility—not always prestige, but participation.

That ethos has also influenced the development of alternative spaces, including Fontanelle, FELTspace, and the late CACSA (Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia), which for decades provided a home for mid-career experimentation. Many of these spaces are now run by artists who came through the very institutions they now critique. This recursive structure—learning, leaving, returning—has given Adelaide’s scene its particular texture.

The South Australian art school tradition has been less about polish than about persistence. It has created a scene that is provisional, experimental, and unusually self-aware. In the studio and on the street, in formal critiques and late-night install hangs, the school continues to serve not just as a training ground, but as Adelaide’s most generative cultural engine—where artists learn not only to make work, but to survive it.

Public Art and the Sculptural Politics of Space

Walk through Adelaide’s centre and you will encounter a city unusually thick with sculpture. Monuments, busts, abstract forms, whimsical interventions, and commemorative plaques appear on corners and in parks, in malls and on campuses. Some are admired, some ignored, and a few actively contested. But none are accidental. In Adelaide, public art has long been treated not as incidental embellishment but as an index of civic identity. The built environment tells stories—some confidently told, others revised or resisted. And those stories, rendered in bronze, stone, steel, and neon, form a peculiar kind of archive: one that is both material and mutable.

Statues, Controversy, and Changing Memory

Adelaide’s earliest public sculptures were monuments—formal, representational, and unambiguous in their messaging. They honoured governors, explorers, philanthropists, and monarchs. Many of these works still stand, most notably:

- The statue of Queen Victoria in Victoria Square (erected in 1894), a commanding bronze presence surrounded by colonial geometry.

- The figure of Colonel William Light, pointing authoritatively over his planned city from Montefiore Hill.

- The sombre memorials to war dead along North Terrace, including the 1925 South African War Memorial.

These works reflect the priorities of their time: imperial loyalty, settler heroism, and a linear sense of historical progress. Their style is largely classical, their symbolism direct. But even in their permanence, these statues have never been immune to critique.

In recent decades, public discourse around such monuments has sharpened. Questions of who is remembered, and how, have led to calls for reinterpretation, contextualisation, or removal. The statue of Edward John Eyre, for example—an explorer whose role in violent frontier conflict is now better understood—has been the subject of debate. While Adelaide has not seen the dramatic removals witnessed in other cities, these statues are increasingly treated as open texts rather than settled statements.

Artists and activists have responded with counter-monuments and interventions. In some cases, this has meant temporary installations near existing statues, offering alternative narratives or drawing attention to historical absences. In others, it has meant the creation of new works that consciously reject the monumental mode in favour of intimacy, ambiguity, or humour.

What emerges from this landscape is a city wrestling, in public, with its past. The meaning of a statue is never fixed. It shifts with its context—with the changing shape of trees, traffic, and political consciousness. Adelaide’s public sculpture now exists in a state of ongoing negotiation.

Malls Balls and the Aesthetics of Everyday Encounter

Perhaps the most beloved public sculpture in Adelaide is also its most baffling: Bert Flugelman’s Spheres (1977), colloquially known as the “Malls Balls.” Two polished stainless-steel globes, stacked and slightly offset, standing in the heart of Rundle Mall. They reflect everything and explain nothing.

When installed, Spheres was divisive. Critics questioned its meaning, its cost, and its relevance. Shoppers bumped into it. Children climbed on it. Over time, though, it became iconic—not despite its opacity, but because of it. It does not instruct or commemorate. It simply exists, playfully deflecting the city around it in warped reflections.

This work marked a shift in Adelaide’s public art: away from commemoration and toward interaction. Flugelman’s sculpture invited touch, selfies, irreverence. It was not about authority but about presence. Its very lack of narrative became its strength.

Other works have followed this logic. In Hindmarsh Square, Greg Johns’ Gateway (1997), a rusted corten steel form with ambiguous curves and voids, frames space rather than declaring meaning. On North Terrace, Hossein and Angela Valamanesh’s collaborative work 14 Pieces (2005), a series of sculptural “pages” emerging from the ground, invites reading, wandering, and interpretation.

These works operate within what might be called the aesthetics of encounter. They do not seek awe. They ask for attention—casual, repeated, evolving. They become part of people’s routines: meeting points, landmarks, or mysteries passed on daily commutes. Their success lies not in message but in integration.

This approach suits Adelaide. A city often wary of grand gestures finds in these sculptures a quieter kind of public dialogue—less about instruction, more about conversation.

Temporary Works, Permanent Debates

The rise of temporary public art—particularly through the Adelaide Biennial, Fringe, and independent commissions—has added new layers to the city’s sculptural life. These works, ephemeral by design, have often been bolder in form and politics. They are not burdened by permanence and can therefore take greater risks.