The Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, known in Czech as Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze (AVU), was founded in 1799. This marked a major turning point in Czech cultural history, establishing the first formal institution dedicated to fine arts education in the region. Its creation was part of a broader Enlightenment movement sweeping across Europe, where art academies were viewed as essential for cultivating refined taste, civic virtue, and a sense of national pride. Within the Habsburg Monarchy, the Academy carried political and cultural importance, serving as a tool for both imperial prestige and local identity formation.

The founders of the Academy included several Czech nobles and intellectuals who wanted to provide a local alternative to Vienna’s dominant Academy of Fine Arts. Count Franz Thun-Hohenstein was one of the chief patrons, and the Academy initially focused on classical drawing, painting, and sculpture rooted in Greco-Roman ideals. These foundations emphasized technical mastery and moral seriousness, both seen as pillars of a proper artistic education. Instruction mirrored the Austrian academic model, where harmony, order, and discipline were valued above personal expression.

The 1799 Establishment and Cultural Context

At the time, Prague was culturally divided between Czech and German influences. The creation of a Czech art academy became an act of quiet resistance against cultural Germanization, allowing local artists to study in their homeland. It also aligned with a growing wave of Czech patriotism that would blossom into a full-fledged national revival later in the 19th century. By training young artists to depict Czech history, landscapes, and traditions, the Academy became a subtle but powerful contributor to the nation’s cultural independence.

Over time, the Academy’s mission expanded beyond mere artistic training. It evolved into a center for cultivating Czech artistic identity in a multi-ethnic empire. This process was gradual and complex, but the Academy’s students began to integrate patriotic symbols and local folklore into their works. These early efforts laid the groundwork for the distinctive Czech art that would flourish in the next century. In many ways, the Academy was not only teaching art—it was nurturing the very idea of a Czech nation.

19th Century Growth and the Rise of Czech Modernism

The 19th century brought enormous growth for the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. After its early decades of consolidation, the school began to establish a reputation for excellence throughout Central Europe. Among its most notable instructors was Antonín Mánes, appointed professor of landscape painting in 1836. His teaching emphasized truth to nature and emotional engagement with the Czech landscape, a theme that resonated with the nationalist sentiment growing across Europe. Under Mánes’s guidance, the Academy’s focus broadened to include more expressive, regionally inspired art.

Antonín’s son, Josef Mánes, born in 1820, became one of the Academy’s most illustrious alumni. Though educated partly under his father’s direction, Josef’s artistic vision carried forward the national ideals his father championed. His famous calendar paintings for the Prague Astronomical Clock, completed between 1864 and 1866, fused folklore, symbolism, and everyday Czech life into a grand patriotic statement. His works reflected a people reclaiming their voice through art, and his influence at the Academy inspired generations to come.

Key Professors and Early Alumni

Other artists shaped the Academy’s reputation during this century. Václav Brožík, born in 1851, rose to prominence after studying in Paris, where he absorbed French academic painting’s refined techniques. Returning to Prague, he became a professor and helped modernize instruction by encouraging his students to study the European masters firsthand. His monumental canvas “Master Jan Hus before the Council of Constance” (1883) captured the Czech reformer’s defiance and became an emblem of moral integrity. Brožík’s approach reinforced the Academy’s role as both an artistic and ethical institution.

By the end of the 19th century, Czech nationalism was inseparable from the Academy’s artistic output. Many graduates contributed to public monuments, historical paintings, and national exhibitions that celebrated Czech identity within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While the Academy retained elements of traditional academicism, it was increasingly characterized by a patriotic spirit. The seeds of modernism were sown during this time, as artists began to question realism and experiment with expressive form and color.

The Interwar Period and Avant-Garde Influence

When Czechoslovakia declared independence in 1918, the Academy entered a new and vibrant chapter. Freed from Habsburg control, the institution now reflected the optimism of a new republic seeking its cultural voice. The school’s leadership encouraged a greater diversity of expression and engagement with international art movements. While still rooted in classical training, the Academy began to open its doors to modernist ideas sweeping across Europe.

The interwar years were intellectually electric. Czech Cubism, which had emerged before World War I, influenced architecture and painting alike, and the Academy’s students could no longer ignore such developments. Artists such as Emil Filla and Bohumil Kubišta, though not always teaching there, shaped the broader artistic discourse that surrounded the school. The Academy’s faculty and students absorbed and debated these trends, gradually incorporating aspects of abstraction and symbolism into the curriculum.

New Currents and Modernist Instruction

The 1920s and 1930s were marked by artistic experimentation at the Academy. Professors encouraged students to study modern forms, including Cubism, Constructivism, and Surrealism. This period coincided with a broader European movement toward experimentation, with Prague becoming a hub of intellectual exchange. Artists such as František Kupka, born in 1871 and one of the pioneers of abstract painting, symbolized the Czech embrace of modern art’s spiritual and intellectual dimensions.

Although Kupka’s mature career unfolded in Paris, his early experiences in Prague and Vienna reflected the educational standards of AVU. His journey demonstrated how Czech-trained artists could compete on the world stage. Inside the Academy, students learned that technical precision and creative innovation were not opposites but complementary forces. By the eve of World War II, the Academy had become both a bastion of Czech identity and a beacon of modernist inquiry.

The Academy During Communism (1948–1989)

The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948 profoundly reshaped the Academy of Fine Arts. The new regime demanded ideological conformity, turning the arts into tools for political propaganda. Socialist Realism became the mandated style, celebrating the laborer, the soldier, and the collective. Freedom of expression, experimentation, and individualism—hallmarks of prewar modernism—were suppressed. The Academy, once a haven of creative independence, now faced rigid control.

Faculty members who resisted were dismissed or sidelined, replaced by politically reliable figures. The teaching of Western art history was heavily censored, and foreign influences were condemned as “bourgeois decadence.” Students learned to produce art that glorified the Communist Party and its ideals. Murals, sculptures, and paintings portrayed industrial progress and agricultural prosperity, masking the regime’s control behind idealized imagery. Artistic innovation retreated underground.

Socialist Realism and State Control

Despite these restrictions, the Academy never entirely lost its creative spirit. Some students and instructors found subtle ways to express dissent through allegory and symbolism. The Prague Spring of 1968 briefly lifted censorship, allowing a surge of artistic experimentation before being crushed by the Warsaw Pact invasion. Figures such as Jiří Kolář, though not formally tied to the Academy, inspired young artists to seek new means of expression outside official channels. Underground exhibitions and private studios became sanctuaries of free thought.

During the “Normalization” era of the 1970s and 1980s, the Academy endured continued pressure, but internal resistance persisted. Some professors quietly introduced students to modernist and conceptual art under the radar of state supervision. These acts of intellectual defiance preserved the continuity of Czech artistic thought. By the late 1980s, as the Communist regime began to crumble, the Academy once again stood poised for renewal. The revolution of 1989 would change everything.

Post-Communist Renewal and Institutional Reform

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, the Academy of Fine Arts underwent rapid transformation. Freed from decades of political control, it redefined itself as a modern European institution dedicated to open inquiry. One of the leading figures of this transition was Milan Knížák, an avant-garde artist and member of the Fluxus movement, who became rector in 1990. His leadership symbolized a complete break from the past—introducing new pedagogical models and integrating contemporary art forms into the curriculum.

The 1990s saw the return of academic freedom and the rediscovery of Western modernism. The Academy reestablished ties with institutions abroad, welcoming visiting lecturers and hosting international workshops. Traditional disciplines like painting and sculpture were reinterpreted in light of new theories about art and society. The focus shifted toward fostering independent thought, critical reflection, and experimentation—a profound change after years of ideological uniformity.

Academic Freedom and Contemporary Curricula

New departments were established, including Intermedia, New Media, and Conceptual Art. The Academy also introduced updated art history and aesthetics programs that reconnected Czech students with previously banned ideas and global artistic developments. Professors encouraged students to combine traditional craftsmanship with new technologies, from video and sound to performance and installation art. The renewed curriculum made the Academy one of the most forward-thinking art schools in Central Europe.

At the same time, the Academy remained grounded in its heritage. Drawing and painting were still viewed as essential foundations, ensuring continuity with the school’s classical past. This balance between tradition and innovation became its defining strength. By the end of the decade, AVU had regained its international reputation as a premier art academy. Its transformation reflected not only political liberation but also a restored faith in the power of creative freedom.

Notable Alumni and Their Impact on Czech Art

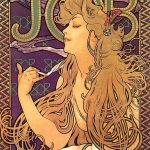

The Academy’s alumni have profoundly influenced both national and international art. Alphonse Mucha, born in 1860, is perhaps the best-known Czech artist of the early 20th century. Though he studied in Munich and Paris, Mucha’s monumental series “The Slav Epic” (1910–1928) was created for Prague and dedicated to the Slavic people’s history. His Art Nouveau style, characterized by graceful lines and patriotic symbolism, became a cornerstone of Czech visual identity. Mucha’s work demonstrated the artist’s lifelong dedication to his homeland and its spiritual values.

Another towering figure is František Kupka, born in 1871, one of the founders of abstract art. Kupka’s philosophical approach to painting—linking color, rhythm, and movement—paved the way for generations of Czech and European abstractionists. His connection to the Academy lay in its emphasis on disciplined drawing and intellectual rigor. Through Kupka, Czech art entered the global modernist conversation, and his example continues to inspire students who see abstraction as a path to freedom.

Influential Figures Across Generations

In more recent times, artists such as Krištof Kintera, born in 1973, and Kateřina Šedá, born in 1977, represent the Academy’s contemporary legacy. Kintera’s installations use humor and technology to comment on modern society, while Šedá’s social projects bring art directly into the public sphere. Both embody the Academy’s spirit of curiosity and engagement with real-world issues. Their success underscores the school’s relevance in shaping artists who are both technically skilled and socially conscious.

Together, these alumni demonstrate the Academy’s enduring influence across generations. They bridge the gap between traditional and experimental forms, between national heritage and global dialogue. Their diverse practices reflect the Academy’s openness to change while maintaining respect for its past. Each new generation adds another layer to the institution’s long story—a story that continues to shape Czech and European art today.

The Academy Today: Programs, Partnerships, and Vision

In the 21st century, the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague stands as a thriving institution rooted in both heritage and innovation. Its programs span a wide spectrum, including painting, sculpture, architecture, restoration, and new media. Students are encouraged to blend these disciplines in search of new creative directions. The school remains a magnet for young artists seeking both technical mastery and conceptual depth, continuing its mission to unite art and intellect.

The Academy’s campus in Letná, Prague, houses studios, galleries, and libraries where history and modernity coexist. Annual exhibitions allow students to showcase their works to the public, reinforcing the connection between education and community engagement. AVU’s academic calendar includes symposia, workshops, and open studios, where visitors can observe students’ creative processes firsthand. The Academy’s reputation for rigor and innovation attracts talent from across Europe and beyond.

Current Offerings and Global Engagement

International cooperation remains a central pillar of the Academy’s philosophy. Through the Erasmus program and partnerships with universities in Germany, France, and the United States, AVU facilitates exchange and dialogue among cultures. Faculty members participate in international research projects and exhibit in prestigious galleries worldwide. The school’s graduates frequently represent the Czech Republic in major biennials and global exhibitions, ensuring that Prague remains an active voice in contemporary art.

Looking toward the future, the Academy continues to invest in interdisciplinary research and digital technologies. Its commitment to public outreach—through lectures, exhibitions, and community projects—keeps art accessible and relevant. More than two centuries after its founding, the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague remains both a guardian of Czech artistic tradition and a laboratory of creative experimentation. Its story is one of endurance, renewal, and the timeless pursuit of beauty and truth.

Key Takeaways

- The Academy of Fine Arts in Prague was founded in 1799 during Habsburg rule.

- Key figures like Antonín and Josef Mánes shaped its early identity.

- The Academy evolved through nationalism, war, and political repression.

- Post-1989 reforms brought academic freedom and artistic innovation.

- Notable alumni include Alphonse Mucha, František Kupka, and Kateřina Šedá.

FAQs

- When was the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague founded?

It was founded in 1799 under Habsburg influence. - Who were some of its most famous alumni?

Alphonse Mucha, František Kupka, and Krištof Kintera are notable examples. - How did Communism affect the Academy?

The curriculum was restricted to Socialist Realism, limiting artistic freedom. - What changes occurred after 1989?

The Academy embraced academic freedom, international exchanges, and contemporary media. - What programs are offered today?

Departments include Painting, Sculpture, Intermedia, New Media, and more.