Portuguese Luminism was a luminous yet contemplative branch of European landscape painting that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rooted in Portuguese Naturalism and influenced by French Impressionism, this movement prized the interplay of light, air, and atmosphere over strict realism. Unlike its French cousin, however, Portuguese Luminism leaned toward quieter, more melancholic moods, reflecting the unique geography and cultural sensibility of the nation. Coastal vistas, riverbanks, and rural fields bathed in soft sunlight became its hallmarks.

Though not a formally defined movement, Portuguese Luminism came to be recognized through the works of key painters who embraced plein-air techniques and emphasized the emotive power of natural light. It emerged from the evolving taste of artists reacting to academic rigidity, seeking instead to paint the living essence of their surroundings. These painters often trained abroad, especially in Paris, and brought home new ways of seeing that they adapted to Portuguese themes and settings. Luminism became a bridge between Naturalism and the early stirrings of modernism in the Iberian Peninsula.

This article explores the evolution and impact of Portuguese Luminism through the lives and work of six key artists, contextualized within the cultural shifts of late 19th-century Portugal. From the rural fields of Carlos Reis to the maritime magic of João Vaz, these painters captured more than light — they preserved national identity in brushstrokes and shadow.

Their work offers an enduring testimony to Portugal’s natural beauty and artistic voice, balancing tradition with the quiet spark of innovation.

What Is Portuguese Luminism?

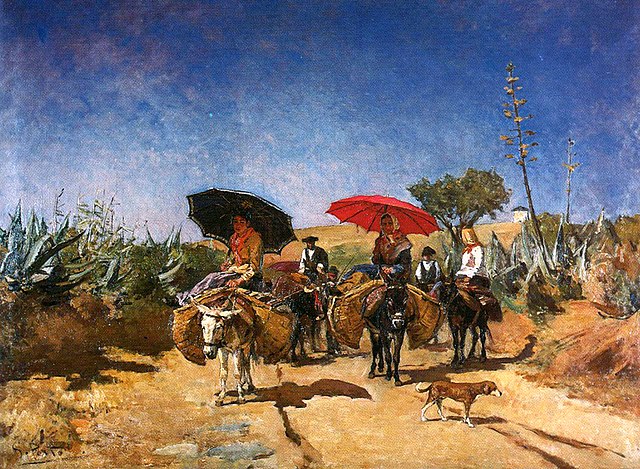

Portuguese Luminism was a style of painting that emphasized the effects of natural light on landscapes and coastal scenes, flourishing between the 1870s and 1930s. While deeply rooted in the Realist and Naturalist traditions of 19th-century Europe, it shifted away from photographic precision toward a more emotive, light-focused approach. It combined technical fidelity with atmospheric beauty, particularly in rural and maritime scenes across Portugal. Often described as Portugal’s answer to Impressionism, it carried a more subdued palette and introspective tone.

This artistic style grew from a reaction to academic rigidity and a desire to explore nature as lived experience, not just visual data. Rather than focusing on modern life in cities, Luminist painters often turned their attention to sunlit wheat fields, coastal harbors, or small countryside villages. Their aim was not to imitate the Impressionists exactly but to find a national way of expressing light and emotion on canvas. They embraced plein-air painting, spending long hours outdoors capturing specific light conditions.

Origins in Naturalism and Impressionism

The movement emerged during a time when Portuguese artists were increasingly exposed to foreign styles, especially through travel and study in France. Many had attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris or worked alongside French Realists and Impressionists. The Barbizon School, with its naturalistic landscapes and outdoor painting, was a significant influence. However, Portuguese Luminism retained a more restrained color palette and often prioritized a meditative tone over spontaneity.

It was also deeply informed by Portuguese Naturalism, which had gained traction in literature and art during the 1870s and 1880s. Writers like Eça de Queirós and painters like Silva Porto sought to describe Portuguese life in authentic detail. Luminism continued this spirit but introduced a poetic lightness and visual lyricism that elevated it beyond documentation. The result was a body of work that married tradition and innovation — and captured Portugal’s landscapes in their most soulful light.

The Cultural Context of Late 19th-Century Portugal

Portuguese Luminism didn’t arise in a vacuum — it developed in a nation undergoing significant transformation in the final decades of the 19th century. Politically, the country was struggling with instability, economic challenges, and the tensions of constitutional monarchy. Culturally, however, it was a time of growth and modernization. The country’s intellectual elite were looking to France for new ideas, especially in the arts and sciences. In this environment, art became both a mirror and a moral compass.

In painting, the influence of academic classicism was still dominant in the 1860s and 1870s, especially within Lisbon’s Academia de Belas-Artes. However, a younger generation of artists began to challenge that paradigm. They wanted to capture everyday life and the natural world through direct observation, not idealized models or historical scenes. Naturalism took hold first, but it would soon soften into Luminism — an evolution from realism into poetry, guided by sunlight and air.

The Role of the Grupo do Leão (Lion’s Group)

A key force in this artistic transformation was the Grupo do Leão (“The Lion’s Group”), formed in Lisbon in 1880. This informal circle of painters, writers, and intellectuals gathered at the Leão d’Ouro tavern, exchanging ideas about modern art and Portuguese identity. Their mission was to elevate Portuguese painting by opening it to European trends while grounding it in national themes. Members included Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro, João Vaz, António da Silva Porto, and others.

They held exhibitions from 1881 to 1889, which helped shift public taste and establish new names in the art world. Although not all members were Luminists in a strict sense, their embrace of plein-air painting, modern themes, and looser brushwork laid the groundwork for Luminism. The group’s emphasis on the natural landscape as a bearer of national spirit would continue to influence Portuguese painters well into the 20th century.

Silva Porto – The Pioneer of Portuguese Plein-Air Painting

António Carvalho da Silva Porto (1850–1893) is widely recognized as the founding figure of modern Portuguese landscape painting. Born in Porto, he studied at the Academia Portuense de Belas-Artes before traveling to Paris in 1873, where he absorbed the techniques of the Barbizon School and painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. He embraced plein-air painting, working outdoors to capture natural light and atmosphere. Returning to Portugal in 1879, he brought these techniques home, reshaping the national approach to landscape art.

His works often depict the Portuguese countryside with earth-toned palettes and delicate brushstrokes. He avoided the bright, almost abstract light of French Impressionism, instead creating a more grounded and contemplative vision. Paintings like Margem do Tejo and Paisagem com Animais show his mastery of mood and tone, turning simple scenes into quiet meditations on rural life. He paid particular attention to how sunlight filtered through trees or shimmered on riverbanks.

Career, French Influence, and Lasting Impact

Silva Porto’s influence extended beyond his canvases. He became a professor at the Lisbon Academy of Fine Arts and mentored several younger painters who would later shape Portuguese Luminism. He also helped organize the first exhibitions of the Grupo do Leão, offering a platform for emerging artists to explore light and color more freely. His writings and teachings emphasized a sincere connection to nature, captured through direct observation rather than strict adherence to academic technique.

Although he died relatively young in 1893, Silva Porto’s legacy endured through the work of artists like Carlos Reis and João Vaz. He is often credited with setting the stage for Luminism by marrying the French plein-air method with distinctly Portuguese subject matter. His dedication to painting light not just as a visual effect but as an emotional presence defines his role as a true pioneer. Today, many of his works are housed in the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea (MNAC) in Lisbon.

João Vaz and the Maritime Soul of Luminism

João José Vaz (1859–1931) carved out a unique space in Portuguese Luminism with his evocative depictions of coastal life and maritime scenes. Born in Setúbal, a city closely tied to the sea, Vaz was deeply influenced by his surroundings from a young age. He trained at the Academia de Belas-Artes de Lisboa, where he distinguished himself early with strong draftsmanship and sensitivity to natural settings. His paintings often feature fishing boats, beaches, and dockside communities immersed in golden light.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who focused on inland scenery, Vaz embraced the sea as a symbol of national pride and identity. His palette was typically soft, often dominated by cool blues, silvery whites, and the gentle glow of sunrise or sunset. He had a remarkable ability to suggest temperature and time of day with subtle tonal shifts. In works like Pescadores na Praia and Cais do Sodré, he translated ordinary coastal life into visual poetry.

The Sea as a Luminous National Symbol

For João Vaz, maritime imagery was more than a stylistic choice — it was a cultural statement. Portugal’s history as a seafaring nation resonated deeply with his generation, and Vaz used this theme to affirm continuity between past and present. His depictions of fishermen and harbor workers conveyed dignity and resilience, elevating humble labor into something almost sacred. Light was his ally in this mission, wrapping his subjects in warmth and serenity.

Beyond painting, Vaz was also an accomplished illustrator and taught at the Escola Industrial Afonso Domingues in Lisbon. He was a key participant in the Grupo do Leão, aligning with its commitment to modernizing Portuguese art while honoring national themes. His teaching and public work helped spread Luminist ideals to a wider audience. His seascapes remain some of the most beloved examples of Portuguese maritime painting, balancing realism with lyrical beauty.

Carlos Reis and the Poetic Vision of the Countryside

Carlos Reis (1863–1940) brought a distinctly lyrical voice to Portuguese Luminism through his depictions of sunlit rural life. Born in Torres Novas, Reis enrolled at the Academia de Belas-Artes de Lisboa in the 1880s and later studied in Paris, where he was influenced by Naturalism and plein-air methods. Unlike more urban or maritime painters, Reis focused on the agrarian world — fields, farmers, harvesters — captured in glowing, atmospheric compositions. He treated rural subjects with deep affection and poetic reverence.

His best-known works, including Ceifeiras and Colheita do Milho, feature women harvesting grain under expansive skies. These are not idealized peasants but dignified figures, portrayed with restraint and warmth. The landscapes around them shimmer with diffused light, creating a feeling of timelessness. Through his brushwork and composition, Reis gave visual expression to the quiet strength of Portugal’s rural communities.

Light, Labor, and the Rural Spirit

Reis believed in the importance of regional identity and national character, and his rural scenes reflect that philosophy. He saw the countryside as the heart of Portugal — steady, unchanging, and noble. His light was not dramatic or high-contrast but soft and glowing, as though the land itself were exhaling at the end of a long day. He was a master at capturing the golden tones of late afternoon and early evening.

In 1911, Reis became director of the Academia de Belas-Artes, a position he held until 1930. He used his influence to champion Naturalist and Luminist styles at a time when avant-garde movements were gaining momentum. His leadership ensured that a generation of painters remained grounded in tradition even while exploring new methods. He was awarded numerous honors during his lifetime, and his work continues to be exhibited in leading Portuguese museums today.

Henrique Pousão – The Luminist in Miniature

Though his life was tragically short, Henrique Pousão (1859–1884) left an outsized legacy in Portuguese painting. Born in Vila Viçosa, Pousão studied at the Academia Portuense de Belas-Artes before earning a scholarship to Rome in 1881, where he developed a style that blended academic technique with luminous realism. His health was frail — he suffered from tuberculosis — and he was often confined to small, manageable studies painted en plein air. These works, usually oil on wooden panels, glowed with intimacy and delicacy.

Pousão’s style evolved quickly during his years abroad. In Italy, he painted quiet street corners, rooftops, sunlit walls, and empty pathways — scenes full of stillness and subtle light. His use of color was restrained yet expressive, with pale ochres, soft blues, and muted greens dominating his palette. His approach suggested both the Realism of earlier Portuguese painters and the atmospheric softness that would define Luminism.

A Brief, Brilliant Legacy

Pousão died in 1884 at the age of just 25, but left behind over 150 known works. His paintings were not widely recognized until after his death, when critics and curators began to see in them a transition from strict realism to a more lyrical, light-driven approach. He is now considered a precursor to Portuguese Luminism, with some even calling him the first true Luminist.

His work is preserved at the Museu Nacional de Soares dos Reis in Porto, where it continues to attract scholarly attention and public admiration. Despite his limited output, his artistic sensitivity and experimental brushwork made him an essential figure in the movement. His quiet, intimate portrayals of architecture and landscape remain deeply moving. Pousão’s legacy lives on not in grand canvases, but in the tender luminosity of his small, glowing studies.

Legacy of Portuguese Luminism Today

Though Portuguese Luminism had its peak between the 1870s and 1930s, its influence can still be seen in the country’s visual culture. As Modernism gained ground in the early 20th century, Luminism was gradually overshadowed by Cubism, Futurism, and later, abstraction. Still, many 20th-century artists retained a fascination with light and landscape, incorporating these Luminist traits into more contemporary forms. The emotional and sensory qualities of the movement continue to resonate today.

Museums across Portugal proudly display works by Silva Porto, João Vaz, Carlos Reis, and others. The Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea, Museu do Chiado, and Soares dos Reis Museum all maintain strong Luminist collections. Scholars have revisited the movement with fresh eyes, recognizing its subtle innovations and cultural importance. Exhibitions in Lisbon and Porto have reintroduced this poetic chapter of art history to new generations.

Influence on 20th-Century Portuguese Art

Even as abstraction and conceptual art took hold, Portuguese painters such as Eduardo Viana and Almada Negreiros carried forward the Luminist attention to national landscape and identity. Contemporary artists like Isabel Sabino and Júlio Pomar have also cited the importance of light and color in their work. Luminism laid the foundation for visual storytelling rooted in place, emotion, and atmosphere.

In this way, Portuguese Luminism is not a closed chapter but an enduring influence — a style that captured the soul of a nation through brush, pigment, and light. It reminds us that even the most fleeting rays of sunlight can tell deep and lasting stories.

Key Takeaways

- Portuguese Luminism emphasized light and mood over strict realism, often in rural or coastal settings.

- It was influenced by French Impressionism and the Barbizon School but retained a more subdued tone.

- Key artists include Silva Porto, João Vaz, Carlos Reis, and Henrique Pousão.

- The Grupo do Leão played a major role in promoting modern Portuguese art.

- Luminism continues to shape Portuguese visual culture through museum collections and artistic legacy.

FAQs

- What is Portuguese Luminism?

It is a painting style focused on natural light and atmosphere, active from the 1870s to early 20th century. - Who were the main Portuguese Luminist painters?

Notable figures include Silva Porto, João Vaz, Carlos Reis, and Henrique Pousão. - What subjects did Luminists paint?

They often painted rural fields, harbors, fishermen, and sunlit landscapes. - Where can I see Portuguese Luminist paintings today?

Major museums in Lisbon and Porto, such as MNAC and Soares dos Reis, have strong collections. - How did Portuguese Luminism differ from French Impressionism?

It used a softer palette and conveyed a more introspective, poetic tone.