Madrid’s art history does not begin with kings or cathedrals, but with stone and fire—etched, daubed, and carved into the plateau long before the city had a name. For centuries, the region that now surrounds Spain’s capital existed as a sparsely populated high plain, its artistic footprint scattered across cliffs, caves, and riverbanks. The art left behind is sparse but compelling: it reveals not only human presence, but imagination, memory, and symbolic intent. These earliest markings were not precursors to greatness. They were complete in their own time, born of spiritual urgency or communal ritual. They mark the beginning of Madrid’s visual history in a place where permanence was never guaranteed.

Paleolithic Echoes: Cave Paintings in the Sierra de Guadarrama

The Sierra de Guadarrama, the granite mountain range that looms to the northwest of Madrid, holds some of the oldest artistic traces in central Spain. Though lacking the grandeur of Altamira or El Castillo, this landscape hides rock shelters with Paleolithic and Neolithic markings—schematic deer, handprints, and abstract motifs rendered in red ochre and black manganese. Sites such as Peña Escrita in the nearby Montes de Toledo region contain vivid figures that suggest a continuity of symbolic practice across millennia.

What survives from this era is fragmentary, often faint to the point of disappearance. Yet even these fragments carry the unmistakable signs of deliberate design. A single painted line, placed in relation to the natural curve of a rock, suggests a mind attuned to more than survival. These images likely held spiritual or communal meaning—perhaps related to seasonal migration, fertility, or territorial claims. The Iberian interior was never empty. Its early artists, anonymous and itinerant, left symbols instead of signatures.

Later, in the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages, rock engravings and megalithic constructions appeared in the wider region. Dolmens near the Madrid–Ávila border suggest the presence of early ceremonial structures, while petroglyphs etched along river routes like the Lozoya and Jarama hint at long-forgotten ritual landscapes. Although these are not strictly “Madrid” in the modern sense, they form part of the same central plateau ecosystem—evidence of human creativity flowing through the geography long before borders fixed it.

Roman Footprints and Visigothic Silences

By the time Rome arrived in the Iberian Peninsula, the central plateau had already hosted a mosaic of pre-Roman cultures: the Carpetani, the Vettones, and the Olcades, among others. The Romans brought new scales of artistic production—mosaics, statuary, inscriptions—and new forms of visual language. Yet Madrid itself, then an unremarkable settlement or perhaps not even a formal habitation, was marginal to the imperial project.

Nonetheless, archaeological discoveries in the surrounding Comunidad de Madrid reveal Roman villas with intricate mosaics, often featuring geometric designs or mythological themes. One striking example, uncovered in the village of Carranque (just south of the capital), includes detailed scenes of Dionysus and Medusa, rendered in tesserae no larger than a fingernail. These were the private luxuries of Romanized elites, their artistry born of imported technique and local labor.

The fall of Rome and the subsequent rise of the Visigothic kingdom left a thinner artistic legacy in the region. Visigothic art, which flourished elsewhere in Spain—such as in Toledo or Mérida—barely touched Madrid, which remained peripheral. Surviving objects are mostly liturgical: fibulae, small crosses, and carved altars from necropolises near Alcalá de Henares or the Manzanares basin. Unlike the classical grandeur of Rome, Visigothic visual culture is cryptic, abstract, and often insular, preoccupied with religious symbolism and formal repetition. It is an art of introversion, befitting a fragmented post-imperial landscape.

Here, a curious paradox emerges: as artistic skill persisted, public visibility declined. The region slid into a kind of visual quiet, its artifacts buried under soil and memory. Madrid’s future greatness had not yet been foretold—not in stone, not in pigment.

Islamic Madrid: The Alcázar and the Geometry of Power

Madrid enters recorded history not through a Christian lens, but through Islamic strategy. In the 9th century, the Umayyad emir Muhammad I of Córdoba ordered the construction of a military outpost called Mayrit—a fortress perched above the River Manzanares, tasked with monitoring Christian advances from the north. Though it began as a garrison, it soon grew into a small town, complete with mosque, baths, and a rudimentary urban structure. This was the true origin of Madrid.

Islamic architecture, even in a frontier town like Mayrit, brought a geometric sophistication absent from earlier Iberian structures. Though most of the original buildings were later destroyed or rebuilt, fragments survive. The base of the old Muslim wall, excavated near the current Almudena Cathedral, reveals finely dressed stonework arranged in interlocking patterns—defensive, but not artless. The nearby Cuesta de la Vega also contains remnants of Islamic urban planning, including water channels and traces of tiled surfaces.

Unlike the narrative of reconquest that would later dominate Spanish national identity, Islamic Madrid was not a historical anomaly. It was part of a larger civilization that spread scientific, philosophical, and artistic knowledge across the peninsula. Even in its modest size, Mayrit carried visual elements now considered hallmarks of Spanish aesthetic tradition: horseshoe arches, stucco reliefs, ceramic tiles glazed in cobalt and turquoise.

Three aspects of Islamic art in Madrid deserve particular attention:

- Calligraphic fragments unearthed from the medieval layers of the city—mostly Qur’anic verses—testify to a culture in which writing was inseparable from beauty.

- Water infrastructure, including fountains and irrigation channels, reflected the Islamic view of urban life as a balance of utility and elegance.

- Decorative abstraction, found in architectural ornament, resisted figural depiction in favor of geometry, revealing a worldview at once mathematical and mystical.

When Christian forces under Alfonso VI captured Madrid in 1085, they did not destroy the city’s Islamic character overnight. In fact, many of its architectural techniques and aesthetic motifs were absorbed, adapted, and Christianized. Mudéjar art—hybrid, bilingual, and brilliant—would emerge from this convergence. But that story belongs to the next chapter.

Madrid’s prehistory, then, is not a blank canvas waiting for culture. It is a palimpsest of modest but meaningful marks: handprints on cave walls, tesserae in rural villas, defensive towers turned into foundations for palaces. These early layers do not predict what Madrid would become, but they ground it in something older than monarchy or modernity: the enduring human urge to shape the world and to leave behind a trace.

The Reluctant Capital: Madrid’s Unearned Rise to Power

Madrid did not ascend to capital status because of artistic brilliance, cultural prestige, or historical centrality. It became the seat of empire through a cold calculation of geography, politics, and control. When Philip II declared Madrid the capital of Spain in 1561, he chose a city without a university, cathedral, or established civic grandeur. It had no ancient lineage like Toledo, no mercantile force like Seville, no ecclesiastical prestige like Santiago. And yet, from this unlikely base, Madrid grew into a furnace of royal patronage and artistic ambition. Its art history begins not with a golden inheritance, but with an institutional vacuum into which the monarchy poured money, talent, and power.

The Habsburg Shift: From Toledo to Madrid

Before Madrid, Toledo had served as the unofficial heart of Castile—a hilltop city layered with Roman, Visigothic, Jewish, and Islamic cultural strata. It was the seat of the archbishopric, home to a powerful nobility, and a center of manuscript illumination and religious art. Moving the court from Toledo to Madrid was, on the surface, inexplicable. But Philip II had different priorities.

Madrid’s central location allowed easier communication across the Iberian Peninsula. It lacked the entrenched elites of older cities, giving the monarchy space to build a capital in its own image. It was also small, quiet, and defensible—an ideal base for a ruler obsessed with surveillance, order, and control.

Yet this strategic emptiness posed a problem: Madrid had no artistic institutions of its own. Everything had to be imported. Artists, architects, and scholars followed the court, and with them came foreign influences, especially from Italy and Flanders. The early Habsburg period was a moment of improvisation and hybridization, as the visual culture of the new capital struggled to find form.

One of the first major commissions was the transformation of the Alcázar—originally a Muslim fortress—into a royal palace. Though it remained architecturally uneven and suffered multiple fires, the Alcázar served as the symbolic and administrative heart of Madrid until its destruction in 1734. Its halls were hung with Italian paintings, tapestries, and religious icons, creating a visual program designed to reinforce Habsburg authority rather than regional identity.

The court also invested in urban infrastructure: roads, fountains, and public squares that began to sculpt the city into a place befitting empire. It was an aesthetic of control, not celebration.

Philip II’s Pragmatism and Patronage

Philip II is often remembered as austere, devout, and reclusive—a monarch more invested in monastic stone than in courtly spectacle. Yet his role in shaping Madrid’s artistic destiny is undeniable. From his isolated palace-monastery at El Escorial (just northwest of the capital), he orchestrated one of the most ambitious building projects in early modern Europe. Though technically outside the city, El Escorial shaped Madrid’s cultural identity as a center of sober magnificence and Catholic orthodoxy.

Philip’s taste in art was deliberately restrained. He collected Titian obsessively, but preferred the elder master’s more contemplative later works over scenes of overt sensuality or triumph. He commissioned sacred paintings, architectural plans, and religious sculptures that aligned with the Counter-Reformation’s strictures on decorum and didactic clarity. These tastes filtered into Madrid through the court’s influence, establishing a visual language that valued gravity, introspection, and symbolic rigor over exuberant flourish.

At the same time, Philip established the basis for the royal collections that would later become the Prado Museum. His acquisitions of Flemish tapestries, Italian canvases, and Iberian altarpieces set the tone for Madrid’s role as a collecting capital. Though not yet an artistic innovator, the city became a gravitational force: artists came to Madrid not to be inspired by it, but to serve it.

- The Flemish painter Antonio Moro became court portraitist, introducing an austere realism that would shape Spanish portraiture for generations.

- The sculptor Leone Leoni, and later his son Pompeo, contributed imperial effigies and bronze medallions that reinforced dynastic legitimacy.

- Architect Juan Bautista de Toledo, trained in Rome and Naples, brought Renaissance vocabulary to the king’s projects, laying the groundwork for what would become Herrerian architecture.

Through these commissions, Madrid absorbed European styles and filtered them through a lens of bureaucratic solemnity.

Absence of Legacy, Presence of Opportunity

Madrid’s lack of a pre-existing artistic identity proved both burden and blessing. On the one hand, it struggled to match the mythic resonance of Rome, the mercantile splendor of Venice, or the religious intensity of Seville. On the other, its very newness allowed it to be shaped entirely by royal ambition.

Artists who came to Madrid often found constraints, but also patronage. The painter El Greco, though famously rebuffed by the court in Madrid before settling in Toledo, understood the city’s ambitions well: in a place governed by divine right and central authority, art had to serve power. Those who stayed adapted to this demand. Bartolomé González, Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, and other court painters developed a visual style that emphasized static majesty, devotional clarity, and unbending hierarchy.

Urban development followed similar patterns. The construction of Plaza Mayor in the early 17th century, under Philip III, created a central civic space that balanced public ceremony with architectural uniformity. Its arcades, balconies, and symmetry expressed a vision of urban life as orderly spectacle. The plaza would become a setting for festivals, executions, and bullfights—a kind of open-air theatre of power.

This emerging visual culture was not experimental or expressive. It was calculated, coded, and hierarchical. It revealed the court’s preoccupation with appearances, but also with control. In this sense, Madrid’s early art history reflects not creativity unleashed, but creativity conscripted.

And yet, something new began to stir in these disciplined forms. Beneath the polished portraits and geometrical plazas lay the seeds of a uniquely Spanish visual identity—one forged not in freedom, but in the paradox of serving empire through the making of beauty. Madrid, born out of royal convenience, was beginning to teach itself how to look.

Baroque Splendor and the Spanish Golden Age

If Madrid’s Habsburg rise was a story of strategic consolidation and imported culture, the 17th century saw the city explode into visual intensity. This was the age when the capital’s artistic infrastructure matured, when its churches swelled with gilded altarpieces, and when Spanish painting achieved unprecedented psychological and formal depth. The Baroque in Madrid was not just decorative; it was performative, doctrinal, and deeply entangled with Spain’s imperial anxiety and Catholic orthodoxy. Its art was built to awe, to convert, to affirm divine and royal order. And yet, some of its greatest achievements came from artists who undermined these ideals from within, turning grandeur into irony, and piety into deeply human drama.

Velázquez at Court: Art in the Service of Monarchy

Few figures dominate Madrid’s artistic history like Diego Velázquez, whose career was inseparable from the Habsburg court. Born in Seville in 1599, Velázquez was summoned to Madrid by Count-Duke Olivares, Philip IV’s powerful favorite. By 1623, he was appointed court painter, a position he would hold for nearly four decades. His studio in the Alcázar became a crucible where politics, portraiture, and philosophy fused into a visual language unlike anything else in Europe.

Velázquez painted the king repeatedly—stoic, withdrawn, dressed in mourning black—as if Philip IV were already a ghost in his own court. Yet the true genius of his royal portraits lies not in flattery, but in their tension. These are images of a monarchy in decline, cloaked in protocol but besieged by inertia. The painter’s brush rendered power not as spectacle, but as burden.

This reach extended beyond the king. Las Meninas (1656), painted late in Velázquez’s life, is both court portrait and metaphysical meditation—a canvas about seeing and being seen, about illusion and reality, about the position of the artist in a world of rigid hierarchies. The Infanta Margarita is the ostensible subject, but the true center is elusive. Velázquez places himself in the act of painting, staring outward at a viewer who may or may not be the king and queen. It is a staggering act of self-placement: the court artist claiming not just presence but authorship.

At the heart of his mature style was an economy of means—a looseness of brushstroke that suggested detail rather than insisting on it. Unlike his Italian contemporaries, Velázquez did not idealize. He studied light, texture, psychology. He painted dwarfs and jesters, drunkards and philosophers, with the same dignity he granted to nobility.

Madrid under Velázquez was a court full of paradox: obsessed with ritual yet vulnerable to collapse, steeped in wealth but increasingly impoverished. His paintings reflect this dissonance without resolving it.

The Catholic Spectacle: Churches, Altarpieces, and Mysticism

While Velázquez articulated royal doubt in paint, the religious institutions of Madrid doubled down on certainty. The Counter-Reformation, in full swing by the early 17th century, demanded a visual culture that was immediate, emotional, and doctrinally correct. Art had to teach, move, and defend the faith. Madrid’s churches became crucibles of this Baroque spectacle.

The Iglesia de San Ginés, San Isidro, and San Antonio de los Alemanes all contain exemplary altarpieces from the period, encrusted in gold leaf, carved in riotous detail, and populated with ecstatic saints. Sculptors like Gregorio Fernández and Pedro de Mena, though based in Castile and Andalusia respectively, supplied works to Madrid’s convents and chapels. Their hyperrealist wooden figures—complete with glass eyes, ivory teeth, and real hair—were meant to provoke awe, tears, and repentance.

Madrid’s version of the Baroque was theatrical. Painted ceilings opened into heaven, angels descended in choreographed clouds, and martyrdoms were shown in gory precision. Yet this intensity was not merely emotional—it was structured to reinforce Catholic dogma at a time when Protestantism had fractured Christendom.

- Juan Carreño de Miranda, another prominent court painter, specialized in religious scenes that combined drama with refined technique, often in service of royal chapels.

- The Carmelite convents of Madrid commissioned imagery of the mystical experiences of Saint Teresa and Saint John of the Cross, anchoring Spain’s unique brand of spiritual interiority in visual form.

- The Jesuits, whose power rose rapidly during this era, introduced a pedagogical form of religious art: instructive, rigorous, and emotionally charged.

Even Madrid’s architecture obeyed the logic of this Catholic theater. Churches were designed with deliberate sightlines, pulling the viewer’s gaze toward the altar or the dome—toward transcendence. The aim was not serenity but intensification: to blur the boundary between heaven and earth.

Plaza Mayor and the Public Eye

Amid this visual drama, Madrid also developed a space for more secular forms of display: the Plaza Mayor, completed in the early 17th century under the reign of Philip III. Framed by uniform façades, accessible arcades, and painted frescos, the plaza was both civic center and ritual stage. Here the city staged bullfights, executions, royal proclamations, and public festivals. It was an art form in urban planning—a formal void surrounded by codified grandeur.

The architect Juan Gómez de Mora designed the plaza with symmetry and stagecraft in mind. Its design reflects the Baroque obsession with framing: the spectacle must be contained, legible, and total. In times of celebration, the entire plaza could be dressed in cloth banners, scaffolding, and firework towers; during autos-da-fé, it became a theater of punishment and purification.

Frescoes added later, notably those on the Casa de la Panadería, introduced mythological and allegorical figures that blended imperial iconography with civic pride. Though decorative, these images served a propagandistic function: affirming the unity of the crown and the capital, sanctifying public space with layers of symbolic meaning.

But beyond these grand rituals, there was also the flowering of popular visual culture: devotional prints, religious processions, street puppetry, and ephemeral art created for festivals. Madrid’s Baroque era was not confined to the palace or the church—it spilled into streets, markets, and homes.

This was the first moment when Madrid ceased to be a stage and became a protagonist in the history of European art. Through the confluence of religious fervor, royal ambition, and popular participation, the city acquired a visual identity both grand and conflicted—beautiful, excessive, and haunted by the knowledge that its wealth and power were already beginning to fade.

Imported Enlightenment: Bourbon Rule and Neoclassical Order

The War of the Spanish Succession ended not just a dynasty, but an entire sensibility. With the death of Charles II in 1700 and the ascension of the Bourbon Philip V—a grandson of Louis XIV—Madrid’s artistic center of gravity shifted dramatically. Out went the introspective solemnity of the Habsburgs; in came the theatrical clarity, rational architecture, and bureaucratic modernism of the French court. The 18th century in Madrid was defined by a concerted effort to remake the capital: to cleanse its medieval clutter, import Enlightenment ideals, and discipline its artistic institutions. The results were uneven but profound, leaving the city with new monuments, museums, and a visual culture pulled between didactic order and expressive resistance.

The Royal Palace and Architectural Absolutism

Madrid’s Alcázar had always been an unstable symbol of royal presence—half fortress, half residence, prone to fire and architecturally inconsistent. Its destruction in a fire on Christmas Eve, 1734, cleared the way for a new expression of Bourbon ambition: the Palacio Real, an immense stone edifice designed to project imperial grandeur on a classically ordered scale.

Built primarily under Philip V and completed during Charles III’s reign, the Royal Palace was modeled in part on Versailles but adapted to the Spanish temperament. Its architect, Filippo Juvarra, and his successor Giovanni Battista Sacchetti, envisioned a palatial structure of white granite and limestone, perched above the Manzanares River, with a symmetrical façade and a strict axial plan. The palace’s vast ceremonial rooms, monumental staircases, and ceiling frescoes—especially those by Corrado Giaquinto and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo—defined a new aesthetic of state: theatrical, secular, and cosmopolitan.

The interior program emphasized allegory over narrative, sovereignty over devotion. Tiepolo’s ceiling fresco in the Salón del Trono (“The Apotheosis of the Spanish Monarchy”) is a paradigmatic example—cloudborne virtues, angels, and personifications swirling around a central image of royal glory. This was not the introspective mysticism of the Counter-Reformation; it was dynastic theater, broadcast in luminous color and cosmic geometry.

But the Royal Palace was more than a residence—it was an anchor for the city’s transformation. Its construction catalyzed a series of urban reforms that would remake Madrid’s streets, parks, and institutions along neoclassical lines.

Mengs, Goya, and the Academic Machine

Bourbon cultural policy was not content with architectural spectacle alone. It aimed to discipline art, to regulate its production, and to align it with Enlightenment values. In 1752, Charles III founded the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, an institution designed to codify taste, train artists, and elevate Spanish art to European standards. Modeled on French and Italian academies, it emphasized drawing from classical sculpture, anatomical precision, and historical painting as the highest genre.

The court painter Anton Raphael Mengs, a German classicist steeped in Winckelmann’s aesthetics, became a central figure in this campaign. His portraits of the royal family, though technically refined, verge on sterile, their idealized features lacking the psychological depth of Velázquez or the theatrical force of Tiepolo. Yet Mengs’s influence on pedagogy was enormous. His teachings shaped an entire generation of Spanish artists and established the Academy’s preference for order, symmetry, and classical restraint.

Into this institutional structure stepped Francisco de Goya, a disruptive presence whose early career was shaped by the very forces he would later question. Goya won prizes from the Academy, studied in Italy, and painted tapestries for the royal factory of Santa Bárbara. These works—cheerful scenes of daily life—masked a restless intelligence that would erupt in later decades.

By the 1790s, Goya had become court painter to Charles IV, producing portraits that slowly edged toward satire. In his famous painting Charles IV of Spain and His Family (1800), he arranges the royals with almost mocking formality: stiff poses, distracted glances, and an awkward sense of composition. He inserts himself in the shadows, behind the canvas—half Velázquez homage, half critique of a court in decay. Goya’s trajectory from academic success to moral witness tracks the unraveling of the Enlightenment’s promises in Madrid.

- His early success owed everything to the Academy and its networks.

- His mature skepticism grew in tandem with his exposure to court corruption and war.

- His late work, especially the Black Paintings, would obliterate the neoclassical ideal from within.

Gardens, Fountains, and the Rational City

Urban reform under the Bourbons extended beyond monumental architecture. It sought to remake Madrid itself as a stage for enlightened citizenship. Charles III, often called “the best mayor of Madrid,” oversaw a vast public works campaign: street paving, lighting, drainage, and the construction of promenades and civic buildings. His aim was not only sanitation and order, but a new visual rationality—a city where aesthetics reinforced governance.

Among the most visible legacies are the Paseo del Prado, a broad boulevard lined with fountains, botanical gardens, and scientific institutions. It was conceived as a space of leisure and learning, a kind of democratic salon where citizens could stroll among allegories and encyclopedic displays. The Fountain of Neptune, Fountain of Cibeles, and Fountain of Apollo, all designed by Ventura Rodríguez, turned mythological figures into civic emblems. They were placed not at random, but as punctuation marks in a new grammar of urban experience.

Parallel to this was the construction of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales, which would later become the Museo del Prado. Though it was initially conceived as a scientific institution, its transformation into an art museum in the 19th century retroactively confirmed the Enlightenment’s visual ambitions: to collect, categorize, and display the world.

This rationalization extended even to religious architecture. Churches from this period—such as San Francisco el Grande, designed by Francesco Sabatini—favor domes, columns, and balanced facades over baroque flourish. The sacred was now housed in the language of classical geometry.

And yet, the Enlightenment in Madrid remained an elite project. For many, its effects were cosmetic rather than transformative. The royal family sponsored public health campaigns and scientific institutions, but censorship persisted, poverty was endemic, and the Inquisition lingered. The city’s new visual order masked deeper tensions, many of which would erupt during the Napoleonic invasions and the political chaos of the early 19th century.

Madrid in the 18th century was a city of surfaces and systems—gleaming fountains, orderly boulevards, and academies filled with plaster casts. But underneath, the contradictions were piling up: an absolutist regime preaching reason, a court sponsoring reform while resisting change, and an art world caught between submission and critique. It would fall to Goya, more than any institution, to reveal the abyss beneath the marble.

Goya’s Madrid: Disillusion, Darkness, and the Birth of the Modern Eye

Francisco de Goya’s Madrid was not the city of Enlightenment promise. It was a place of flickering gaslight and whispered denunciations, where royal decrees clashed with mob violence and superstition held its ground beneath marble façades. Goya arrived in Madrid a dutiful apprentice of neoclassical decorum, but he ended as its most devastating critic. No artist before or after has captured the capital’s psychological terrain with such unflinching intensity. Through his work, the city emerges not as a backdrop but as a protagonist: fractured, volatile, and haunted by the twin specters of power and fear.

Court Painter and Chronicler of Decay

When Goya was appointed court painter to Charles IV in 1786, he was forty years old and already well-versed in the protocols of academic art. His early portraits were elegant, attentive to costume and status, and free of overt critique. Yet even in these commissioned likenesses—such as The Family of the Infante Don Luis (1783)—there is a disquieting informality, a sense that the viewer is intruding on something too private, too fragile.

That tension would deepen as Goya gained access to the highest circles of power. In Charles IV of Spain and His Family (1800), the royal family stands rigid in stiff silks and glinting medals, bathed in unnatural light. Behind them, barely visible, Goya paints himself at his easel—echoing Velázquez’s Las Meninas, but without the sense of confidence. Here, the monarchy is not commanding but hollow. Historians have often debated whether the portrait is satirical, but the real force lies in its ambiguity. The figures are both real and embalmed, tender and absurd.

Goya was no revolutionary, but he was a realist with a conscience. As Spain’s political order fractured under the weight of Napoleonic invasion and court intrigue, his art became less about portrayal and more about testimony.

His two paintings commemorating the French occupation of Madrid—The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808—are unambiguous in their moral fury. In the former, civilians attack French troops in a chaotic street melee; in the latter, French soldiers methodically execute Spanish captives beneath a black sky. The contrast is deliberate. One is a convulsion of rage, the other a mechanical massacre. In both, Goya strips away neoclassical symmetry and Baroque spectacle, replacing them with raw immediacy and terror.

This was not patriotic myth-making. Goya had no illusions about heroism. The figures he painted were frightened, dirty, and human. What mattered was the act of bearing witness—not for glory, but for memory.

The Executions of the Third of May and the End of Hope

The Third of May 1808 may be the most consequential painting in Spanish history. Commissioned years after the events it depicts, it was Goya’s response to the savagery unleashed by both sides during the Peninsular War. In it, a group of condemned men kneel and stagger beneath a firing squad. A man in a white shirt raises his arms in surrender or martyrdom—his pose echoing Christ, yet his face twisted in horror. The soldiers, faceless and mechanical, form a single unit of death, their rifles aligned in perfect sync.

This was a direct refutation of Enlightenment ideals. Reason had not tamed violence; it had, if anything, armed it with new efficiency. Goya does not idealize the victims, but he refuses to aestheticize the violence. The light in the scene—emanating from a lantern on the ground—illuminates only suffering. There is no divine glow, no moral resolution.

And crucially, there is no landscape. The world has vanished. Madrid is implied but invisible, reduced to dirt and stone and blood. In earlier centuries, the city had stood as a theater of power and display. Now, it dissolves into background, eclipsed by the enormity of death.

This painting was not shown publicly until years after Goya’s death. In his lifetime, there was no reward for honesty.

The Black Paintings and the Private Catacomb

In the final years of his life, Goya retreated to a house on the outskirts of Madrid known as the Quinta del Sordo—the House of the Deaf Man. There, between 1819 and 1823, he painted a series of nightmarish images directly onto the plaster walls of his home. These were not commissions. They were private visions, unshown, unsigned, and profoundly unsettling.

The so-called Black Paintings are unlike anything else in European art. They include Saturn Devouring His Son, Witches’ Sabbath, Fight with Cudgels, and The Dog—each steeped in existential dread, madness, and silence. Their palette is restricted to browns, blacks, and sickly yellows. Their figures are deformed, spectral, grotesque. And yet, they are unmistakably contemporary—not allegories, but symptoms.

Saturn Devouring His Son is perhaps the most iconic: a god, crazed and naked, rips the body of his child with bloodied fingers and eyes wide with terror. The classical reference is just a pretext. What Goya paints is the pathology of power—the instinct to destroy what one fears.

The Dog, a near-abstract image of a lone canine’s head rising from a brown slope against an empty sky, may be the most modern painting of the 19th century. Its meaning is unknowable, its emotion overwhelming. It is not about politics or mythology, but about being alone in a void that does not answer.

These works were discovered only after Goya’s death and later transferred to canvas by restorers. But their original context—a private home, never meant for exhibition—suggests something more intimate than despair. They are exorcisms, visual attempts to rid the mind of what history had placed there.

Goya’s deafness, which began in the 1790s, may have intensified his isolation, but it also sharpened his vision. Cut off from polite society, he saw more clearly than any court flatterer or academic theorist. Madrid, in his late work, becomes a haunted zone: no longer capital of empire, but capital of disillusion.

By the time he left Spain for Bordeaux in 1824, Goya was a man out of place and out of time. He had chronicled the fall of the old order and the failure of the new. He had painted kings and lunatics, martyrs and monsters. His Madrid was not the city of rational squares or golden palaces—it was a city of quiet screams, flickering shadows, and indelible truth.

From Revolution to Ruin: 19th-Century Turmoil and the Fragmenting of Tradition

Madrid in the 19th century was a city in perpetual crisis—political, social, and artistic. The century opened with foreign occupation and closed with national humiliation. In between came civil wars, royal restorations, assassinations, failed republics, and the collapse of empire. This instability fractured the capital’s cultural institutions, splintered its artistic communities, and disrupted its relationship with tradition. The grand narratives of faith and monarchy no longer held unchallenged authority. In their place emerged a heterogeneous visual culture: part Romantic, part realist, increasingly skeptical, and deeply entangled with the violence of the street.

Romantic Rebels and the Persistence of History Painting

In the decades following Goya’s departure, Madrid’s art scene struggled to define itself. The Royal Academy still held sway, but its neoclassical ideals felt increasingly detached from a society lurching between revolution and repression. Into this breach came the Romantic painters—not radicals in the Parisian sense, but artists who chafed at academic rigidity and sought to recover history as a site of drama, nationalism, and melancholy.

José de Madrazo, who had studied with Jacques-Louis David in Paris, became both a prominent painter and director of the Prado Museum. His monumental canvases and institutional reforms helped preserve the status of history painting as the premier genre. But it was his son, Federico de Madrazo, who brought a more fluid, painterly elegance to portraiture, combining Romantic flair with a lingering courtly touch.

Still, the most powerful Romantic works of the period emerged not from harmony but from conflict. Antonio Gisbert’s The Execution of Torrijos and his Companions on the Beach at Málaga (1888), now housed in the Prado, is a vast and anguished tableau. Depicting the failed liberal uprising of 1831, it places the viewer just moments before the gunshots. The men stand calm, dignified, lit by a cold Mediterranean dawn, while the soldiers prepare their rifles. The painting is both memorial and indictment—a clear echo of Goya’s Third of May, updated for a new generation of martyrs.

Yet even this commitment to heroic tragedy was slipping. By mid-century, the audience for grand historical canvases was shrinking. The art world, like the nation, was fragmenting.

Art, Exile, and the Madrid Salon

The political upheavals of the 19th century forced many artists into exile—whether abroad, in ideological retreat, or within private commissions. Some followed the court when it relocated, others fled censorship, and still others drifted into obscurity. The result was an art scene that, while geographically centered in Madrid, was emotionally unmoored.

The Madrid Salon—modeled on its French counterpart—attempted to provide coherence. These public exhibitions, organized by the Academy, offered a platform for artists to display their work and compete for state commissions. But the Salon quickly became a battlefield of styles and ideologies. Traditionalists clung to polished mythological scenes and Catholic themes. Others—realists, social critics, and proto-modernists—pushed for art that reflected contemporary life.

One of the most significant developments of this period was the slow infiltration of French artistic influence. Painters like Eduardo Rosales, after studying in Rome and Paris, returned with a more dramatic, gestural approach to composition. His Doña Isabel la Católica Dictating her Last Will and Testament (1864) exemplifies this blend of Spanish historical consciousness and Romantic theatricality. The queen, pale and dying, lies in bed, surrounded by advisors in shadow. It is not a triumphal image, but a meditation on decline.

Meanwhile, Mariano Fortuny, though based in Barcelona and Rome, gained prominence in Madrid with his dazzling technique and orientalist subjects. His watercolors and small oil paintings—bright, intricate, and full of shimmering surfaces—offered a luxurious escape from the grim political reality. They sold well, particularly to foreign collectors, and helped shift taste away from grand narrative toward private pleasure.

But even as Madrid’s elite collected decorative art, the city around them was erupting with protest.

The Rise of Costumbrismo and the Madrid Street Scene

Amid political chaos and academic fatigue, a new style took hold: costumbrismo, a genre focused on the observation of everyday life. It was not radical in form, but it marked a decisive shift in subject matter. Artists turned their attention to taverns, markets, festivals, and the lower classes. Their works depicted Madrid not as a capital of empire, but as a city of noise, color, and contradiction.

Leonardo Alenza, a mordant observer of urban life, painted satirical scenes that teetered between comedy and despair. His Satire on Romantic Suicide (1839) shows a fashionable young man shooting himself while a servant yawns in the background. It is both a jab at Romantic affectation and a bleak portrait of modern alienation.

Others, like Joaquín Domínguez Bécquer, rendered street vendors, musicians, and beggars in picturesque detail. These paintings often walked a fine line between documentation and caricature, sentiment and condescension. Yet they also captured a city that no official portrait could represent—a Madrid of smells and shouts, of muddy boots and smoking cigarettes.

Three recurring motifs dominated this street-level art:

- The majo and maja—flamboyantly dressed lower-class figures who embodied Madrid’s local color and defiant charm.

- Religious festivals, especially those of San Isidro and the Virgin of Almudena, where sacred ritual merged with street spectacle.

- Urban trades and professions, from knife-grinders to street preachers, each rendered with ethnographic attentiveness.

This turn toward the vernacular had implications beyond subject matter. It suggested that Madrid’s identity was not in its palaces or museums, but in its people—in their gestures, dress, and defiance.

As the century wore on, this insight deepened. Artists began to explore themes of poverty, alienation, and moral ambiguity with greater frankness. The aesthetic was still realist, but the content had changed. Madrid was no longer a city to be idealized. It was to be survived, analyzed, and—occasionally—laughed at.

By the 1890s, the capital had become a palimpsest of contradictions: a fading imperial city filled with anarchists, poets, police, and painters. The glories of the Golden Age were long past. The Enlightenment had failed to civilize politics. And yet, amid the rubble of illusions, a new modern eye was beginning to emerge—one that would shape Madrid’s next generation of artists, writers, and thinkers.

A New Century, a New Language: Modernism in Madrid

The dawn of the 20th century in Madrid was not greeted with triumph but with exhaustion. The 1898 loss of Spain’s last overseas colonies—Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines—struck the capital like a national funeral. The once-great empire had collapsed, and its cultural institutions seemed adrift. Out of this vacuum rose a generation of writers, thinkers, and artists determined to strip Spanish identity down to its roots and rebuild it in new, modern terms. Madrid, at the heart of this effort, became a crucible for experimentation, defiance, and aesthetic self-invention.

Modernism in Madrid was not a monolith. It ranged from Symbolist decadence to socialist realism, from poetic abstraction to political caricature. What united its practitioners was a refusal to inherit the visual language of decline. Their Madrid was not the city of kings or saints, but of cafés, typewriters, theater marquees, and psychological uncertainty.

The Generation of ’98 and the Visual Avant-Garde

The Generation of ’98 was not an art movement per se, but a loose constellation of intellectuals—including Miguel de Unamuno, Azorín, and Pío Baroja—who sought to make sense of Spain’s spiritual and cultural crisis after the 1898 defeat. Their influence on Madrid’s artists was indirect but profound. They rejected academic historicism and called for an art that engaged with Spain’s stark landscapes, existential dilemmas, and moral contradictions.

Visual artists began to follow suit. Madrid-based painters like Darío de Regoyos, though previously aligned with Impressionism, moved toward a bleaker realism that echoed the disillusionment of the era. His España negra series (though earlier in conception) remained influential for its haunting images of rural superstition and social stagnation—an aesthetic both modern and archaic.

Yet it was the younger generation, coming of age around 1910, that pushed Madrid’s visual culture into the modernist sphere. José Gutiérrez Solana painted funeral processions, puppeteers, and bullfights with a grotesque intensity that prefigured Expressionism. His Madrid is a world of death masks and religious mania, carnival and rot—drawn in thick strokes and ominous shadows.

Solana’s work exemplifies a key strand of early 20th-century Madrid art: modernism not as liberation, but as confrontation. The city was not a gateway to Parisian light, but a battleground of repression and revelation.

Meanwhile, the influence of symbolism, art nouveau, and Jugendstil arrived via poster design, book illustration, and theatrical scenography. Artists like Rafael de Penagos brought sinuous linework, eroticism, and fashion illustration to the fore, while magazines such as Blanco y Negro and Nuevo Mundo provided platforms for visual experimentation that blurred the line between commercial and fine art.

Residencia de Estudiantes and Cross-Pollination

No institution was more important to Madrid’s modernist ferment than the Residencia de Estudiantes, founded in 1910. Modeled on the Oxford-Cambridge collegiate ideal and imbued with Krausist humanism, the Residencia served as a free-thinking enclave for young artists, scientists, and philosophers. Its alumni and visitors would form the backbone of Spain’s 20th-century avant-garde.

Federico García Lorca, Luis Buñuel, and Salvador Dalí all passed through its halls, alongside physicists like Severo Ochoa and poets such as Pedro Salinas. The atmosphere was electric with debate, performance, and experimentation. The visual artists among them—often untrained in the academic sense—turned to collage, automatic drawing, and surrealist symbolism.

Dalí, before decamping to Paris, painted several early works in Madrid, combining the melancholy of El Greco with Cubist fragmentation and dream imagery. Though his mature style would be forged abroad, the DNA of his strangeness was already present in his Madrid years.

The Residencia also hosted international figures, including Albert Einstein, Le Corbusier, and Paul Valéry, who brought with them the intellectual shockwaves of European modernism. Madrid’s artists, while always working under the shadow of delayed reception, responded with increasing urgency.

This environment of cross-disciplinary fertilization led to innovations in theater design (by figures like Benjamín Palencia), experimental typography, and magazine art that helped push Madrid’s visual language beyond oil and canvas. The walls between the arts were porous. The stage became a painting. The poem became a poster.

Yet this openness did not last.

Sorolla, Zuloaga, and the Spanish Identity Crisis

Even as avant-garde circles flourished in pockets, the dominant public image of Spanish painting in early 20th-century Madrid was split between two poles: Joaquín Sorolla and Ignacio Zuloaga. Both were masters of their craft. Both were internationally successful. And both represented opposing visions of Spain.

Sorolla, based in Madrid but spiritually rooted in Valencia, painted sunlit beaches, shimmering fabrics, and luminous family scenes. His massive murals for the Hispanic Society of America—now housed in the Sorolla Museum in Madrid—offered an idealized, regionalist vision of Spain: vibrant, diverse, and almost entirely devoid of conflict.

His technical skill was extraordinary. In Paseo a orillas del mar (1909), the movement of sheer white dresses in sea breeze seems to dissolve the boundary between pigment and air. Yet Sorolla’s popularity with the bourgeoisie made him, to some, a painter of pleasant evasions—art that soothed rather than confronted.

In contrast, Zuloaga painted Spain’s darker soul. His subjects included matadors, penitents, ascetics, and decaying aristocrats—figures often posed against barren Castilian landscapes or shadowy interiors. His palette was earthier, his lighting more theatrical. Zuloaga’s Madrid was a city of ancestral ghosts and spiritual extremes.

Critics often viewed the two as symbolic adversaries:

- Sorolla: Mediterranean light, optimism, cosmopolitanism.

- Zuloaga: Castilian severity, tradition, fatalism.

But both, in their own way, struggled with the same question: what is Spain, and how can it be shown?

As the 1920s progressed, neither answer felt sufficient. The country—and Madrid with it—was entering another period of political instability, soon to rupture into civil war. Artists increasingly turned to new forms: photography, caricature, film, and graphic design. The canvas no longer held all the answers.

The language of modernism had been spoken in Madrid, often fluently. But its speakers were about to be silenced, scattered, or radicalized. The city’s art scene, vibrant and divided, stood unknowingly on the edge of catastrophe.

Madrid in Ruins: Art and Civil War

Between 1936 and 1939, Madrid ceased to function as a city in the ordinary sense. It became a besieged capital, a frontline, a bunker, a symbol. The Spanish Civil War, ignited by a failed military coup against the elected Republican government, tore the country in half and turned its cultural center into a site of physical devastation and ideological warfare. Artists in Madrid responded with urgency, desperation, and courage—but also, in some cases, with complicity. The war unleashed not only bullets and bombs, but a cultural cataclysm that would destroy institutions, silence voices, and forever alter the trajectory of Spanish art.

The violence came from both sides. Madrid was bombed by Franco’s forces, subjected to starvation and artillery fire. But within the city itself, Republican militias carried out arrests, assassinations, and church burnings. Art, once a vehicle of identity and beauty, became a battleground of propaganda, resistance, and often, casualty.

The Bombing of the Prado and the Exodus of Culture

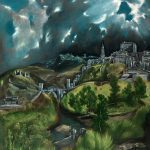

Madrid’s most revered artistic monument, the Museo del Prado, stood perilously close to the front lines during the early months of the war. As shells fell across the city, the museum’s staff—led by director Pablo Picasso’s friend, José Lino Vaamonde—undertook an emergency operation to evacuate its treasures. Paintings by Velázquez, Goya, El Greco, and Titian were crated, padded, and transported under cover of night to Valencia, then on to Catalonia, and eventually to Geneva for safekeeping under the auspices of the League of Nations.

This effort was both heroic and symbolic. The Republican government framed the evacuation not merely as preservation, but as a defense of Spanish culture against fascism. Posters and speeches invoked the Prado as the soul of the nation. But beneath the rhetoric was real peril. Several buildings adjacent to the museum were hit by bombs. A shell damaged part of the museum’s roof. One more strike could have incinerated centuries of Spanish visual history.

The evacuation exposed a deeper anxiety: that Spain’s heritage no longer belonged safely to Spain. Painters, conservators, and curators fled the capital, taking with them more than paintings—taking knowledge, memory, and trust. In a war that destroyed churches and libraries, the museum became both a sanctuary and a target.

Meanwhile, across the city, cultural sites burned. Republican militants, particularly in the early weeks of the war, torched convents, churches, and private collections associated with the old regime. Hundreds of artworks were lost—altarpieces hacked apart, sculptures mutilated, canvases consumed by fire. Some of this destruction was anarchic, driven by hatred of the Church and aristocracy. Other acts were deliberate executions of the past.

The Nationalists would later commit their own cultural violence—not with fire, but with censorship, purges, and ideological imposition. Neither side protected art universally. Each side saved what it wanted, and destroyed what it feared.

Republican Murals and Propaganda Posters

Despite the trauma, or because of it, Madrid during the war saw an explosion of visual propaganda. Artists, designers, and printmakers created thousands of posters, murals, and pamphlets for the Republican cause. These were not subtle works. They were bold, graphic, and meant to be read at a glance: rifles, red flags, shattered swastikas, clenched fists, mothers, soldiers, slogans.

The posters, many printed by the Sindicato de Dibujantes Profesionales, combined Soviet-inspired visual language with distinctly Spanish themes—bulls, flamenco, the silhouette of Don Quixote. Some of the finest examples came from José Bardasano, Carlos Sáenz de Tejada, and Manuel Monleón, artists who had worked in advertising or publishing and now turned their skills to wartime persuasion.

Walls became canvases. Murals adorned workers’ clubs, schools, even trenches. One striking example was the series of anti-fascist murals painted on the walls of the Círculo de Bellas Artes—a prewar cultural center now converted into a propaganda hub. These murals blended socialist realism with surrealist distortion, turning ordinary citizens into giants of defiance.

But this visual campaign had a chilling counterpart. As the war intensified, the Republican zone—including Madrid—became home to mass executions, including the infamous Paracuellos massacres, where thousands of political prisoners, clergy, and suspected right-wing sympathizers were executed and buried in mass graves. Some of the same walls that bore murals of liberation were silent witnesses to state terror.

There was no clean side. There was only survival, and expression under siege.

Visual Witnesses: Photographers, Filmmakers, and Survivors

Not all war art was propaganda. Some of it bore witness—fragmented, terrified, urgent. The war in Madrid was documented by Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and David Seymour (Chim), whose photographs captured both combat and civilian suffering. Capa’s image of a boy playing soldier amid rubble is as unsettling as his more famous frontline shots. These photographs, later published in European and American magazines, shaped international perception of the war as a human catastrophe, not just an ideological struggle.

In cinema, Luis Buñuel, briefly active with the Republican Film Service, worked on newsreels and documentary projects that blended surrealism with reportage. Though much of his wartime work was lost or unfinished, it revealed an artist trying to wrest control over images in a world disintegrating under violence.

Other witnesses created more personal forms of testimony. The painter Antonio Rodríguez Luna, a committed Republican, fled Madrid after the war and later painted his memories in exile—dark canvases of bombed-out streets and skeletal figures. His work is lesser-known but viscerally powerful, a private Goya for a forgotten generation.

And then there were the silences. Many of Madrid’s most promising artists were imprisoned, executed, or exiled. Ramón Puyol, Maruja Mallo, Benjamín Palencia—each experienced displacement, marginalization, or suppression. The war did not only destroy buildings. It fractured trajectories. It broke the future.

In the end, the art of Civil War Madrid offers no redemption. It does not resolve. It accuses, remembers, fragments. It is not about winners or losers—it is about what is lost when a nation turns on itself.

When Franco’s forces finally entered Madrid in March 1939, the city was physically broken and culturally hollowed. The Nationalist victory would bring stability of a kind—but it was the stability of silence, surveillance, and official truth. The war had ended. But the violence of erasure was just beginning.

Under the Shadow: Art in Franco’s Madrid

When Francisco Franco marched into Madrid in 1939, the city was already half-ruin. Bombed, starved, and ideologically splintered, it bore little resemblance to the restless cultural capital of the prewar decades. The Nationalist victory was not only military—it was also a program of cultural imposition. In Franco’s Spain, and particularly in Madrid, art became both a tool and a casualty of authoritarian control. What could not be used to affirm the regime’s ideology was silenced, repurposed, or buried.

Yet even under this weight, creativity persisted. Some artists found ways to adapt, others resisted in quiet forms, and a few exploited the system’s preferences to secure state commissions. But the air had changed. Madrid’s art world was now haunted by exile, censorship, and the eerie stillness of a city where dissent had been driven underground.

Censorship, Conformity, and the Official Style

Franco’s cultural policy in the 1940s and 1950s was reactionary by design. The regime sought to restore a mythic Spain: Catholic, imperial, unified. This meant exalting the Old Masters—particularly Velázquez and Zurbarán—as paragons of national genius, while condemning modernist experimentation as degenerate or foreign. Museums were reorganized to serve this narrative. Exhibitions had to conform to ideological scrutiny. Abstraction was suspect; Surrealism was often banned outright.

The Real Academia de Bellas Artes once again became a gatekeeper, promoting a conservative style rooted in late 19th-century academicism. Government support flowed toward artists who painted religious subjects, heroic Spanish history, or rural idealizations of peasant life. Aesthetic innovation was treated as moral deviance.

In this atmosphere, Antonio López García, then a young painter, began producing hyper-realist images of Madrid that were meticulous, subdued, and emotionally opaque. His early work conformed to acceptable subject matter—portraits, still lifes, empty streets—but its atmosphere of psychological stagnation subtly mirrored the mood of postwar Spain. López was not a political dissident, but his art captured something deeper: the suffocating quiet of a city that had buried its trauma without resolving it.

At the other end of the spectrum were regime-affiliated artists like José María Sert, who painted large-scale murals in state buildings and churches. Sert’s style—baroque, bombastic, laden with allegory—suited Franco’s desire for a visual language of dominance. His works, such as the monumental apse fresco in the Basílica de Santa María la Real de Covadonga, reflected a fusion of religious fervor and nationalist grandeur.

Art, for the regime, was a means of restoration. But it was also a means of forgetting.

Informalism and the Quiet Revolt

By the late 1950s, however, cracks began to show in the cultural edifice. Spain’s isolation after World War II was giving way to tentative reengagement with Europe and the United States. This opening—combined with the exhaustion of academic painting—created space for a new, apolitical abstraction that could bypass censorship without directly confronting it.

This was the age of Informalism: an aesthetic of texture, gesture, and material experimentation. Painters like Manuel Millares, Antoni Tàpies, and Antonio Saura created works that were abstract but emotionally volatile—scraped surfaces, twisted forms, scorched colors. Millares, who used torn burlap and sand to evoke wounds and decay, presented his work not as protest, but as existential reflection. Yet to those who had survived the war and its aftermath, the symbolism was unmistakable.

Though many of these artists were based in Barcelona or abroad, Madrid became a key node in this network of resistance-by-abstraction. The Galería Juana Mordó, opened in 1964, provided a crucial platform for artists working outside the approved aesthetic. Exhibiting Saura, Luis Feito, and Lucio Muñoz, Mordó’s gallery cultivated an audience for art that refused narrative, ideology, or submission.

This wasn’t protest art in the usual sense. It was a language of interior exile—a way of articulating trauma without direct confrontation. Abstract expressionism, in Franco’s Spain, became a form of code.

Three traits characterized this underground avant-garde:

- Material intensity: works used unconventional surfaces—wood, sand, cloth—as expressive media.

- Gesture as meaning: brushstrokes were not marks but actions, evoking pain, effort, or release.

- Ambiguity as shield: by avoiding figuration, artists avoided censorship—without compromising on emotional truth.

This was a Madrid where a painting could bleed without showing blood.

Madrid’s Art Underground: Cafés, Collectives, and Small Magazines

Beneath the regime’s sanctioned culture, a parallel Madrid art world flourished in hushed conversations, backroom exhibitions, and ephemeral publications. Artists, poets, filmmakers, and musicians gathered in private studios and modest cafés—spaces that offered respite from the official narrative and a place to imagine other futures.

Among the most significant gathering spots was the Café Gijón, a haunt of poets, philosophers, and frustrated artists. It served as an informal academy where ideas were shared, arguments erupted, and friendships forged across aesthetic and ideological lines. Here, the spirit of prewar intellectual Madrid flickered, tenuous but unextinguished.

Small publishing houses and journals like Revista de Occidente, Poesía Española, and Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos printed essays, reviews, and occasional visual supplements that engaged with international movements in coded language. Exhibitions were organized in private homes, alternative venues, or sympathetic embassies—creating a kind of shadow infrastructure for cultural life.

One vivid example of quiet defiance was the work of Equipo Crónica, a Valencia-based collective that frequently exhibited in Madrid. Their pop-art-inflected style, referencing Velázquez and Goya through irony and political commentary, offered a sharp contrast to the pious heroism of regime-sponsored art. Their pieces were often censored or altered—but never fully suppressed.

By the 1970s, as Franco aged and the regime began to soften its grip, Madrid’s underground scene grew bolder. Artists began to test the limits of tolerance, smuggling subversion into performance, installation, and conceptual work. The air was thick with tension: anticipation, exhaustion, and the first stirrings of post-dictatorship possibility.

Franco died in 1975, and with him died the pretense that Spanish culture could remain frozen in a 17th-century ideal. But his shadow would linger. The silence had lasted too long to be quickly dispelled.

The city emerged blinking into democracy—uncertain, hungry, and ready for upheaval. The transition would be chaotic, glorious, and irreversible.

The Movida Madrileña: Explosion After Dictatorship

When Francisco Franco died in 1975, the silence cracked open. Within a few years, Madrid transformed from a city of repression into a stage for one of Europe’s most unruly cultural awakenings. The Movida Madrileña—a chaotic, exhilarating eruption of art, music, film, design, and performance—did not emerge from government policy or academic institutions. It came from the streets, from the nightclubs, from bedrooms turned into studios. It was messy, juvenile, provocative, self-destructive, and essential. After decades of censorship, artists in Madrid were no longer asking for permission. They were making up the rules as they went.

The Movida was not a movement with manifestos or leaders. It was a sensation—an attitude more than an ideology, a refusal rather than a program. It was punk and pop, kitsch and camp, erotic and grotesque, deeply local and wildly cosmopolitan. And it changed the way Spain—especially Madrid—saw itself.

Almodóvar, Alaska, and the Visual Codes of Freedom

No figure captures the spirit of the Movida more vividly than Pedro Almodóvar, the filmmaker who emerged from Madrid’s underground scene to become one of the most acclaimed directors in the world. His early films—Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980), Labyrinth of Passion (1982), Law of Desire (1987)—were low-budget, absurd, saturated with color and irreverence. But beneath the jokes and provocations was a new visual logic: Madrid as a playground of liberated identities.

Almodóvar’s Madrid was filled with drag queens, porn stars, junkies, priests, housewives, and rock singers—all bumping into each other in neon-lit apartments and crumbling stairwells. The sets were cluttered, the costumes outrageous, the performances theatrical. But this was not parody. It was a reclamation of space—a declaration that all bodies and all stories were now admissible on screen.

Alongside Almodóvar, musicians like Alaska (Olvido Gara), frontwoman of the band Kaka de Luxe and later Alaska y Dinarama, helped establish a new visual and sonic iconography for the city. With her shock-pink hair, exaggerated makeup, and irreverent lyrics, Alaska became a living artwork: a moving poster for a Spain reborn through pastiche, irony, and attitude.

Graphic designers like Ceesepe and Ouka Lele captured the aesthetics of the time in posters, photography, and illustrations. Their works blended cartoon vulgarity with surrealist whimsy—part Warhol, part Lorca, filtered through LSD and the Madrid metro. Magazine covers, fanzines, record sleeves, and storefronts became canvases. High and low art dissolved into one another.

- Ceesepe’s posters for early Almodóvar films were visual riots—hand-drawn, fluorescent, and self-consciously juvenile.

- Ouka Lele’s photography staged mythic, saturated tableaus of androgynous figures, flamenco gods, and urban saints.

- Carlos Berlanga, both painter and pop musician, shifted seamlessly between easel and keyboard, blending musical hooks with visual elegance.

This was the visual language of a generation that had grown up under dictatorship and wanted nothing more than to reject solemnity. Irony was its armor. Excess was its ethic.

Design, Graffiti, and Gallery Culture in Malasaña

The geographical heart of the Movida was Malasaña, a working-class neighborhood northwest of Gran Vía. Formerly known for its run-down tenements and shuttered shops, Malasaña became a breeding ground for nightclubs, squats, design studios, and underground galleries. The district’s very architecture—tight alleys, creaking balconies, leftover industrial spaces—lent itself to reinvention.

Nightclubs like Rock-Ola, La Vía Láctea, and Pentagrama functioned as both dance floors and salons. Musicians, painters, poets, filmmakers, and fashion designers mingled, collaborated, and sometimes collapsed on the same beer-stained floor. La Movida was as much nocturnal as visual: many ideas were scrawled on napkins at 4 a.m. and enacted before lunch the next day.

One of the most dynamic forms of public art in this era was graffiti, still largely illegal but increasingly embraced by a younger generation of artists who saw Madrid’s walls as blank canvases. Inspired by New York street art but infused with Spanish slang, Catholic iconography, and political sarcasm, Madrid’s graffiti scene became its own genre. Figures like Muelle, whose spiral tag became ubiquitous across the city, bridged the gap between vandalism and style.

At the same time, the gallery world began to shift. Spaces like Galería Juana de Aizpuru and Galería Moriarty began exhibiting younger, riskier artists—installations made of trash, performances that involved nudity and bodily fluids, conceptual art that spoofed advertising and government propaganda.

Three characteristics defined this new gallery culture:

- Interdisciplinary practice: artists worked across media, often blending painting, music, theater, and video.

- Provocation as principle: themes included sexuality, drugs, gender fluidity, and the grotesque—subjects long forbidden.

- Ephemeral forms: many works were designed to decay, be destroyed, or vanish after a single performance.

This was not art for eternity. It was art for now.

The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo and New Institutions

By the mid-1980s, Spain’s new democratic government began to institutionalize the Movida’s energy, attempting to preserve and promote contemporary art within more official frameworks. The creation of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Madrid (MAC), located in the old Conde Duque barracks, was emblematic of this shift. The museum’s collection included many Movida-era works and served as a bridge between underground expression and public legitimacy.

But not everyone was pleased. Some veterans of the scene saw the move toward institutional recognition as a domestication of the revolution. What had once been raw, cheap, and illegal was now curated, catalogued, and sponsored.

Still, the creation of MAC, along with expanded programming at the Círculo de Bellas Artes and early efforts to develop the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, signaled that Madrid was serious about embedding contemporary art in its civic identity. For the first time in decades, young artists could see a future that didn’t involve exile, silence, or compromise.

The Movida was already fragmenting by the late 1980s. AIDS, heroin, commercial saturation, and sheer burnout took their toll. Some artists died young; others retreated. The wild energy cooled.

But the city had changed. Forever. Madrid was no longer a shadow-capital hiding behind its Golden Age. It had become a capital of invention, noisy, plural, ungovernable in the best sense.

The wreckage of dictatorship had not been cleaned up. It had been painted over, danced on, and filmed in Technicolor. And the art was no longer in service of the state. It was in service of life.

Madrid Today: Museums, Money, and the Marketplace

Contemporary Madrid presents a paradox: a city steeped in artistic legacy, yet locked in an ongoing struggle between institutional preservation and commercial ambition. The aftermath of the Movida Madrileña gave way to a cultural landscape that is both richer and more fractured. On one hand, Madrid is now a global capital for art tourism, with some of the world’s finest museums concentrated in a walkable corridor. On the other, it faces the same pressures that afflict major cultural hubs everywhere: market-driven taste, gentrification, and the uneasy blending of spectacle with substance.

The city’s visual culture today is a complex ecosystem. Its major museums function as sites of historical prestige and soft power. Its galleries and fairs serve collectors as much as artists. And its neighborhoods—from Lavapiés to Chamberí—sustain a churn of experimental art, activism, and reinvention that resists easy packaging.

The “Golden Triangle”: Prado, Reina Sofía, and Thyssen-Bornemisza

Madrid’s art axis—informally known as the “Golden Triangle of Art”—is unique in Europe. No other city boasts three museums of such complementary strength within such close proximity. Together, they form the public face of Madrid’s artistic identity. But each institution tells a different story.

The Museo del Prado, established in 1819, remains the soul of the city’s artistic memory. It houses canonical works by Velázquez, Goya, El Greco, and Titian, as well as extensive collections of Flemish and Italian masters. In recent decades, the Prado has sought to expand its scope beyond its 16th- to 18th-century core, organizing exhibitions that highlight overlooked figures—women painters, lesser-known religious art, and global interconnections. Yet it still functions as a cathedral of the past: immersive, awe-inspiring, and fiercely protective of tradition.

Just down the Paseo del Prado lies the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, founded in 1992 as Spain’s flagship institution for modern and contemporary art. Its crown jewel is Picasso’s Guernica, which now hangs in a climate-controlled gallery under strict guidelines—a piece both revered and politically charged. The museum also houses important works by Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, and Maruja Mallo, and curates exhibitions that engage with contemporary crises: migration, labor, memory, and protest.

The Reina Sofía has increasingly positioned itself as a critical institution, one that resists the neutralizing effects of the market and aligns itself with leftist and global discourses. Not all viewers embrace this stance, but the museum’s intellectual rigor has helped anchor Madrid in international debates around decolonization, state violence, and the politics of the archive.

The third vertex is the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, based on the private collection of the Thyssen industrial family and opened to the public in 1992. Unlike the Prado and Reina Sofía, the Thyssen offers a survey collection: early Renaissance panel paintings, Dutch genre scenes, 19th-century Romanticism, and American pop art. It is less ideologically driven, more panoramic. Its success lies in its breadth—and in its ability to attract international visitors who want a compact encounter with Western art history.

Together, these three museums create a dense zone of artistic immersion. But they also point to a question Madrid continues to ask: Who owns culture—the state, the market, or the people?

Corporate Patronage and the New Art Economy

While public museums define the city’s prestige, Madrid’s contemporary art scene is increasingly shaped by private institutions, foundations, and fairs. The line between collector and patron has blurred, and cultural capital is often indistinguishable from financial capital.

The annual ARCOmadrid fair, founded in 1982, has become one of Europe’s premier art markets. It draws galleries from across the globe, with a strong presence of Latin American art and a growing focus on Africa and Southeast Asia. For Madrid’s collectors, ARCO is a place to acquire. For its artists, it is an opportunity—and a test. Success at ARCO can make or break a career. But the fair also represents a shift: from Madrid as a place of artistic production to Madrid as a platform for art as investment.

Private foundations have stepped into this terrain with growing influence. The Fundación MAPFRE, backed by the insurance conglomerate, mounts high-quality exhibitions that range from photography retrospectives to deep dives into early modernism. The Fundación Juan March balances avant-garde historical shows with music and lecture programming. Both institutions curate with professionalism and ambition, but their dependence on corporate sponsorship raises perennial questions about curatorial independence and the softening of critique.

Meanwhile, private collecting has boomed. Figures like Helga de Alvear, whose collection now has a dedicated museum in Cáceres, and galleries such as Elba Benítez and Travesía Cuatro maintain satellite spaces in Madrid, often representing Spanish and Latin American artists to the global market. These entities fund residencies, publications, and commissions—but they also filter what gets seen and sold.

Madrid’s contemporary art world is not corrupt, but it is stratified. A handful of collectors, curators, and dealers set the tone. Beneath them, hundreds of artists labor in relative obscurity. Visibility depends as much on networks as on merit.

Three structural shifts define this new economy:

- The rise of hybrid spaces: bookstores, cafés, co-working labs that double as galleries or event spaces.

- The commodification of street art: graffiti once prosecuted is now curated, branded, or reinterpreted for gallery walls.

- The tension between global relevance and local urgency: art that travels sells; art that speaks only to Madrid often vanishes.

In this environment, artists must navigate with care. The system offers visibility, but at the cost of autonomy.

Art Fairs, Globalization, and the Madrid Art Scene

Beyond ARCO, Madrid hosts a growing constellation of art fairs and festivals that reflect its increasingly global profile. Drawing Room Madrid, Hybrid Art Fair, and JustMAD cater to younger collectors and more experimental forms. PHotoEspaña, founded in 1998, has become one of Europe’s top photography festivals, exhibiting work across galleries, museums, and public spaces each summer.

These events bring energy, internationalism, and cash. They also put pressure on the local scene to remain competitive, fluent in global aesthetics, and tuned to shifting discourses. Artists who once focused on studio practice now maintain social media strategies, grant portfolios, and international residencies. The language of contemporary art—installation, postcolonial critique, archival intervention—has been largely imported, and sometimes sits uneasily with Madrid’s specific history.

Yet for all the globalization, the city still produces intensely site-specific work. Artists like Cristina Lucas, Javier Vallhonrat, and Santiago Sierra continue to engage with the politics of Spain, of memory, of the post-Franco condition. Their work may appear in Venice or Kassel, but its soul remains rooted in Madrid’s scars.

New artist-run spaces, especially in Lavapiés, Carabanchel, and Usera, have created micro-communities that resist both institutional hegemony and commercial dilution. These spaces—often barely funded, precariously legal—host performances, video art, lectures, and workshops that bypass both ARCO and the museums. They form an essential part of Madrid’s cultural metabolism: fast, fragile, and sometimes invisible.

Madrid today is a city of multiple art histories in simultaneous motion. The Golden Age remains at the Prado. The vanguard continues at the Reina Sofía. But between those poles, in cafes, apartments, repurposed garages, and pop-up galleries, the next chapters are being drafted—often with little money, little fame, and fierce urgency.

The city is not finished. It may never be. But its art continues to insist on presence.

Ghosts in the Gallery: Memory, Identity, and the Future of Madrid’s Art

In Madrid, the past is never quite past. Its cathedrals and palaces endure, but so do its absences: the vanished exiles, the purged archives, the memories that remain politically unsettled. Contemporary artists in the city now face a double challenge—how to live in a global present while reckoning with a national past that refuses to rest. The resulting work is diverse in form but often united by a shared urgency: to explore not only who Madrid was, but who it might still become.

The question is not just historical. It is ethical, spatial, and aesthetic. Madrid is filled with ghosts—of war, repression, resistance, and invention—and the city’s most vital art today does not try to exorcise them. It gives them space to speak.

Public Monuments and Contested Memory

Madrid’s physical landscape is saturated with monuments. Some celebrate saints or kings; others glorify a version of Spanish unity that many now find unbearable. For years after Franco’s death, the dictatorship’s visual markers—street names, plaques, statues—remained largely intact, protected by inertia and institutional reluctance. But beginning in the early 2000s, a new politics of memory emerged, driven by victims’ associations, activists, and artists.

One of the most symbolic flashpoints has been the debate over the Valle de los Caídos—a monumental basilica and burial site near Madrid built with forced labor during the dictatorship. Long presented as a site of “national reconciliation,” it in fact contained the remains of Franco himself, until his exhumation in 2019. The visual aesthetics of the monument—monolithic, Catholic-imperial, hewn into mountain rock—continue to provoke deep unease.

Inside Madrid proper, the removal of Franco-era street names, such as Avenida del Generalísimo, and the renaming of plazas and buildings, has generated both praise and backlash. Artists have entered this terrain not with slogans, but with gestures—subtle, ironic, and forensic.