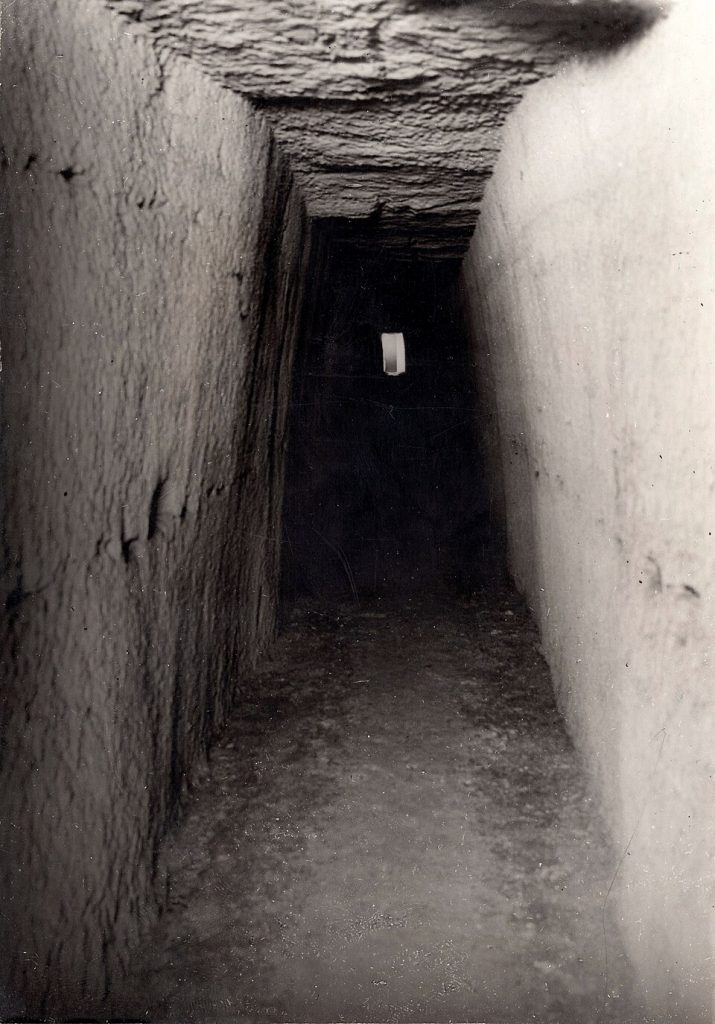

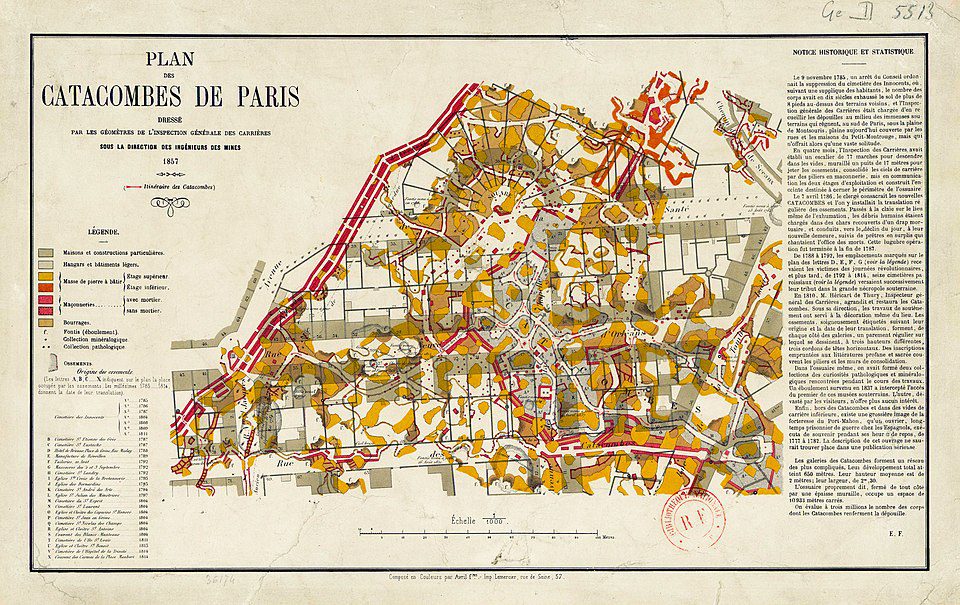

Beneath the glittering streets of Paris lies a darker, more somber world: the Paris Catacombs. This immense subterranean labyrinth stretches over 200 miles, though only a small portion is open to the public. Constructed in the late 18th century as a response to overflowing cemeteries, the Catacombs were originally a solution to a public health crisis. By 1786, bones from Saints Innocents and other burial grounds were systematically moved into the abandoned limestone quarries under the city.

The transformation of these tunnels into an ossuary wasn’t merely practical—it quickly acquired symbolic and cultural weight. As Enlightenment ideals clashed with traditional religious practices, the notion of confronting mortality head-on became increasingly acceptable. Parisians began viewing the ossuary as a meditative space where the line between reverence and morbid fascination blurred. By the 19th century, visits to the Catacombs were already becoming a popular pastime for the curious elite.

The Catacombs as Cultural Obsession

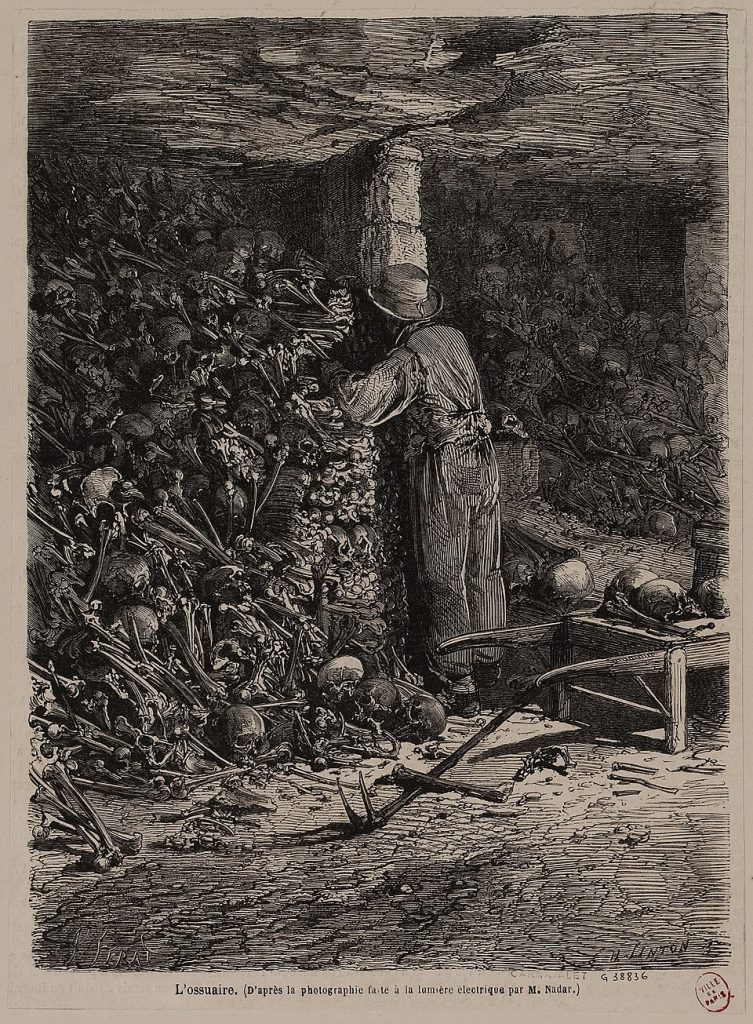

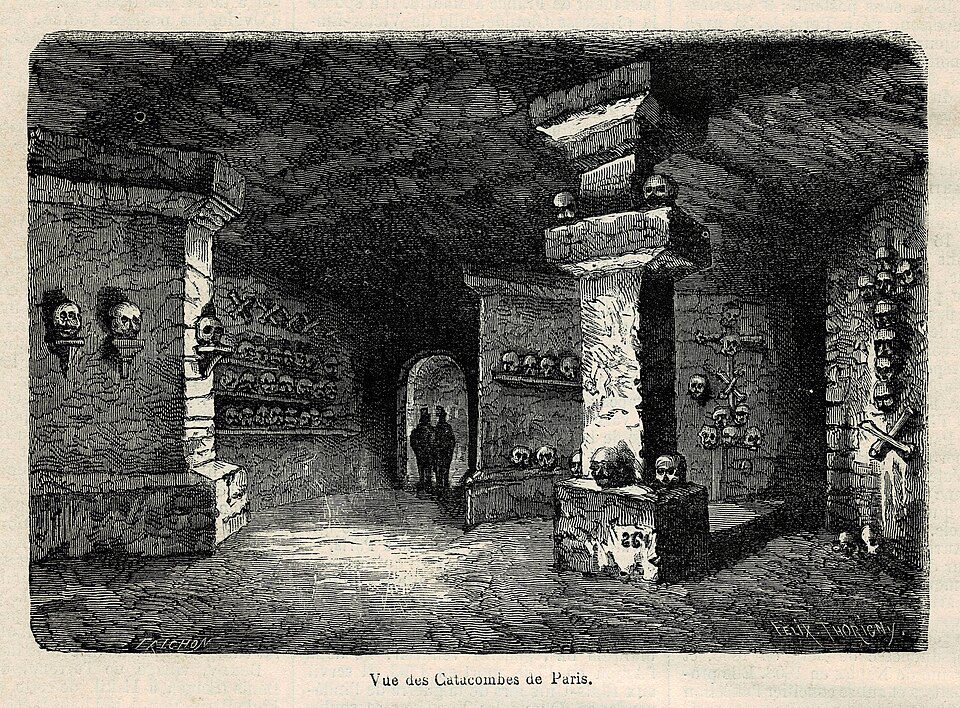

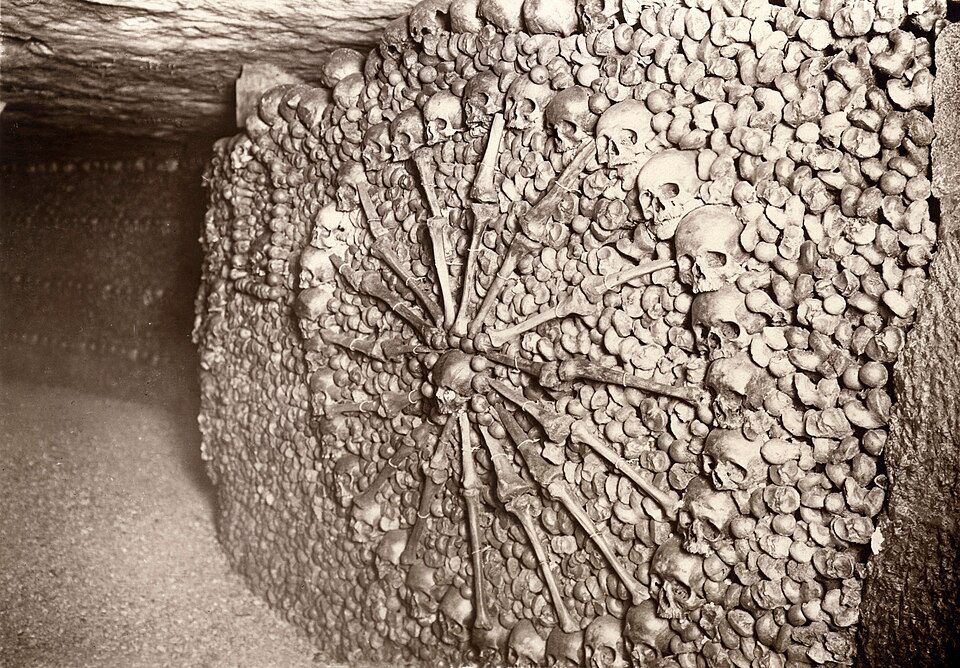

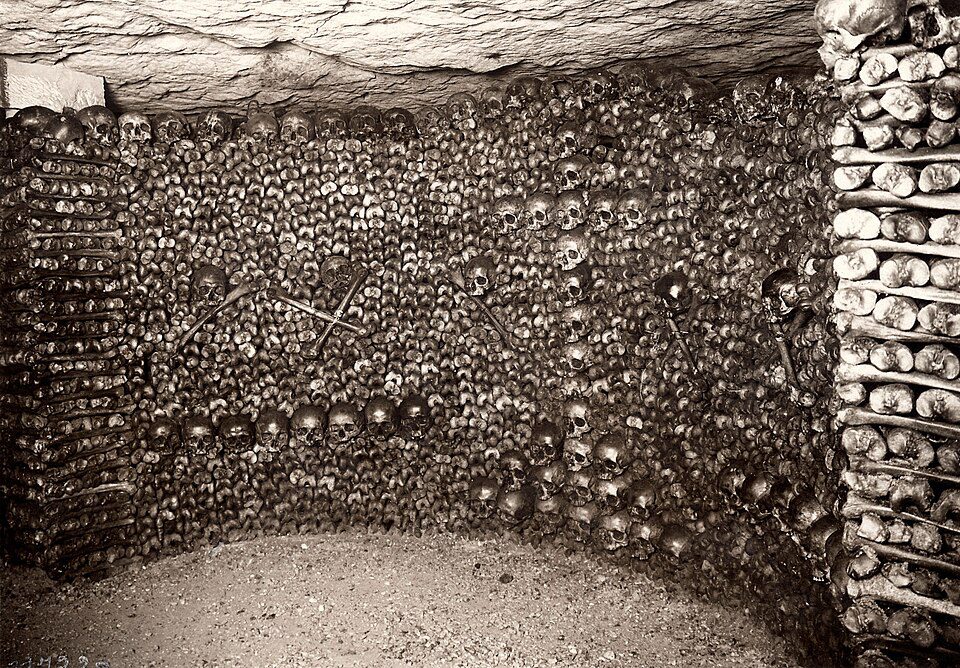

The bones were often arranged with intentional care, creating patterns, crosses, and walls of skulls that hinted at an artistic eye behind the grim task. The earliest arrangement work is credited to Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, who oversaw major renovations between 1810 and 1814. His decisions made the Catacombs both navigable and visually striking, embedding an aesthetic logic into a space filled with human remains. These decisions elevated the space from a mere repository of bones into a visual and emotional experience.

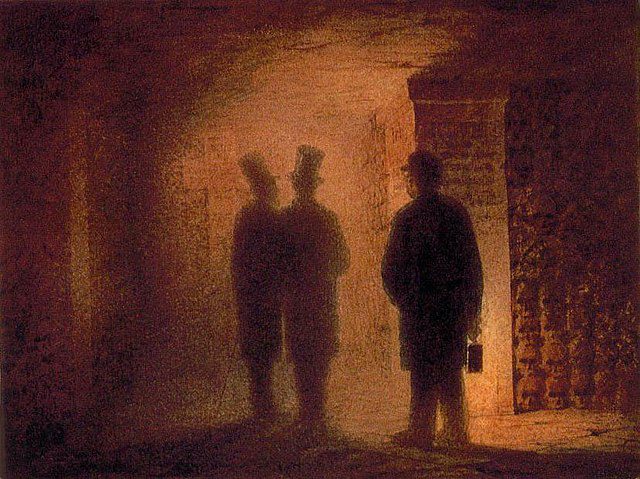

Over time, artists, writers, and mystics alike found inspiration in the Catacombs. Their haunted corridors were referenced in 19th-century Gothic literature, and later appeared in visual art, photography, and film. The eerie ambiance and ever-present reminder of death made it fertile ground for the Romantic imagination. Even today, modern artists and urban explorers continue to be drawn to the catacombs not just for their mystery, but for their raw visual power.

Architecture of the Dead: Aesthetic and Design

The architecture of the Paris Catacombs reflects a unique union of practicality and symbolism. Originally, these were just stone quarries—abandoned and forgotten beneath the growing city. But after the cemetery crises of the 18th century, the tunnels became a carefully structured ossuary. The bones of over six million people were placed here, forming walls, arches, and columns made entirely of femurs and skulls.

The architectural layout was designed to impose order on death. Unlike chaotic mass graves, the Catacombs display a reverence for symmetry and proportion. One of the most striking elements is the “Barrel of Bones,” a central pillar made entirely from stacked skulls and tibiae. These arrangements evoke the Neoclassical emphasis on order, form, and geometric balance, even in the face of death and decay.

Macabre Design as Moral Lesson

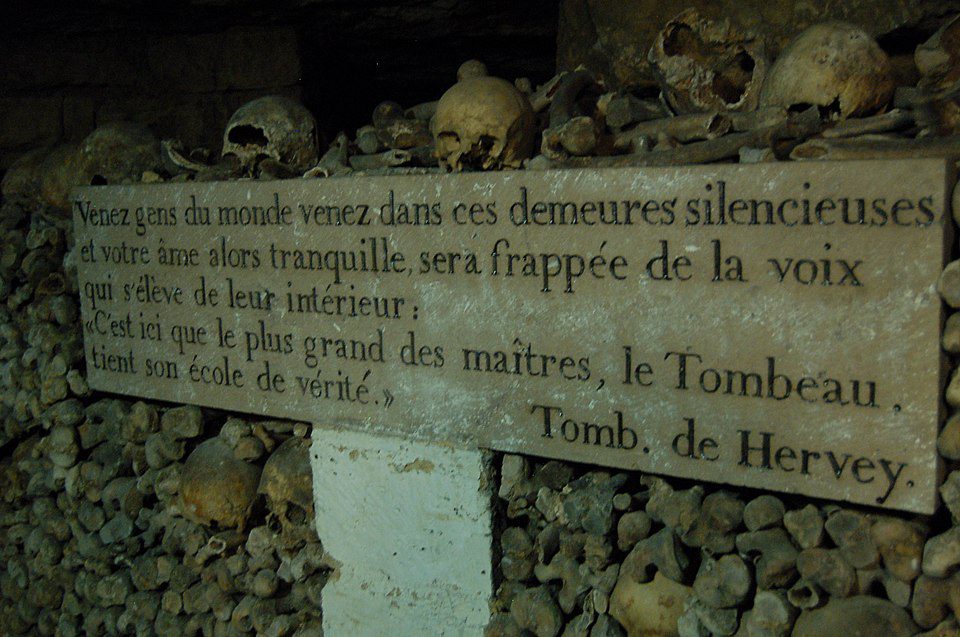

There is more to the Catacombs than just their visual appeal. The bone arrangements often carry moral or spiritual messages. Inscriptions above entrances or embedded in the walls—many of them drawn from the Bible or classical philosophy—remind visitors of their own mortality. The phrase “Arrête, c’est ici l’empire de la mort” (“Stop, this is the empire of death”) is perhaps the most iconic, and sets the tone for the entire experience.

These artistic decisions weren’t accidental. The early 19th-century custodians wanted to ensure that the space prompted reflection, not revulsion. Architectural techniques such as the use of corbeling, archways, and alcoves help guide the viewer’s eye and underscore the meditative nature of the space. While stark, the design insists that death is neither chaos nor oblivion—it is, rather, an ordered passage from one state to another.

Ghost Stories and Urban Myths of the Catacombs

Among the twisted tunnels of the Catacombs, countless ghost stories have taken root over the centuries. The most famous legend involves Philibert Aspairt, a doorman who disappeared in 1793 while searching for a hidden liquor cache and was found 11 years later, just feet from an exit. His body was identified by his janitor’s keyring, and a plaque now marks the spot of his demise. His story became a symbol of the dangers lurking beneath the city’s surface.

Other tales speak of shadowy figures, spectral lights, and disembodied whispers echoing through the limestone corridors. Some cataphiles—those who illegally explore the restricted zones—report feelings of unease, sudden temperature drops, and even visions of lost souls. While skeptics chalk these experiences up to low oxygen or overactive imaginations, the stories persist. Such tales contribute to the Paris Catacombs’ enduring reputation as one of the world’s most haunted places.

The Myths That Refuse to Die

In recent years, more modern legends have emerged. One particularly persistent tale describes a man who filmed himself wandering through the tunnels in 1990, only to drop his camera and vanish. The footage, later supposedly discovered by cataphiles, became the subject of documentaries and online debates, though its authenticity remains unproven. Yet the myth of the “lost explorer” continues to capture imaginations.

Another popular story involves the so-called “midnight tours,” illegal excursions conducted in the dead of night. These covert gatherings are said to include séances, rituals, or even sacrifices, though most accounts are likely exaggerated. Regardless of their truth, these myths function as cultural artifacts, revealing our fascination with what lies beneath the surface—both literally and metaphorically.

Artistic Interpretations of the Paris Catacombs

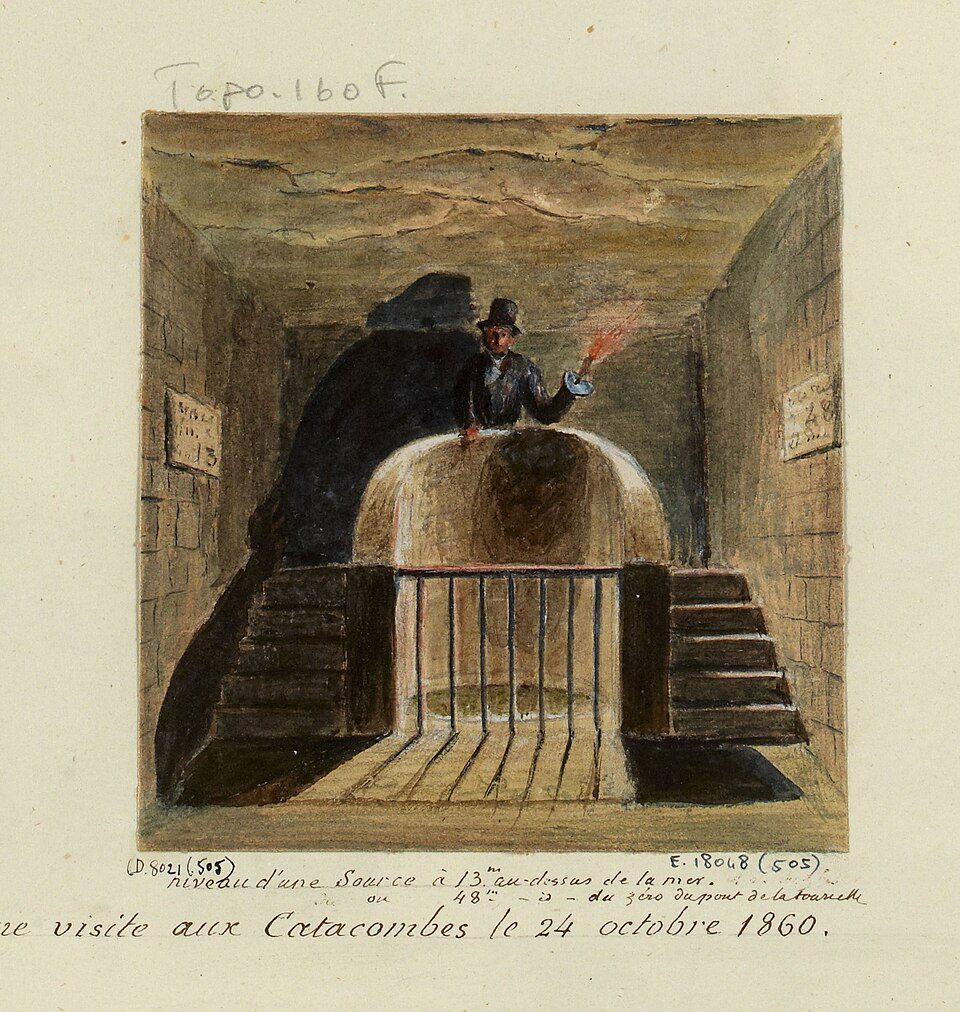

Artists have long been captivated by the Paris Catacombs, interpreting them through various mediums. In the 19th century, photographer Félix Nadar famously descended into the tunnels with cumbersome equipment to capture their eerie grandeur. Born Gaspard-Félix Tournachon in 1820, Nadar is credited with some of the first underground photography ever taken, bringing the hidden world of the Catacombs to light for curious Parisians. His images presented a stark, almost spiritual meditation on space and silence.

Painters and illustrators soon followed. Romantic artists like Gustave Doré created etchings and lithographs inspired by the Catacombs’ moral and symbolic depth. Their chiaroscuro compositions often echoed the dim torchlight and cavernous ceilings of the actual site. In the 20th century, Surrealists such as André Breton and Salvador Dalí viewed the Catacombs as a real-world portal into the subconscious. Though not all ventured inside, the atmosphere of death and decay deeply influenced their work.

Modern Expressions and Digital Rebirths

In recent years, the Catacombs have emerged as a touchstone in digital and installation art. Parisian artist Gaspard Delanoë projected videos onto Catacomb walls during illegal performances in the early 2000s, blending shadow and memory. Street artists like Zevs and Psychose have left graffiti messages that question life, capitalism, and mortality. Their work isn’t preserved in museums—it’s constantly at risk of being painted over or collapsing into dust.

In horror cinema and video games, the Catacombs have also found a home. The 2014 film As Above, So Below fictionalized the tunnels as a Dantean hellscape, drawing on both ghost legends and artistic references. Game franchises such as Assassin’s Creed Unity and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare have recreated the Catacombs in vivid detail, introducing them to audiences worldwide. Whether through brush, lens, or pixel, the Catacombs remain a muse of grim fascination.

Symbolism and Allegory: Death in French Visual Culture

French visual culture has long been obsessed with themes of mortality and decay, and the Catacombs are a central emblem in that tradition. The aesthetic of memento mori—Latin for “remember you must die”—is deeply embedded in both the layout of the Catacombs and the art it has inspired. From the 17th-century vanitas paintings to 19th-century Symbolism, French artists repeatedly used death to comment on the transience of beauty and power. The Catacombs gave that symbolism a physical form.

Religious symbolism also plays a vital role in the Catacombs’ design. Many of the bone arrangements resemble Christian crosses or altarpieces, subtly reinforcing the idea of redemption through death. Inscriptions throughout the tunnels offer biblical warnings, reinforcing a moralistic tone. The architecture thus becomes a kind of cathedral to the dead, reminding visitors that their time, too, will come.

Romanticism and Gothic Undertones

During the Romantic era (roughly 1800–1850), death took on a new role in French art and literature—as a sublime and often beautiful force. Writers like Victor Hugo and painters such as Théodore Géricault saw tragedy and decay as sources of moral truth. The Catacombs fit neatly into this worldview. Their shadowy depths and quietude symbolized a return to the natural order, where all men are equal in death.

Compared to other European ossuaries, the Paris Catacombs offer a particularly refined sense of design and philosophical intent. The Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic features chandeliers of bones, while the Capuchin Crypt in Rome is more ornamental. The Catacombs, by contrast, reflect a distinctly French restraint—more architectural than decorative. That aesthetic restraint gives the site its power: it is not theatrical, but quietly profound.

Artists Who Ventured Below: Known and Unknown

Many artists have been drawn to the Catacombs not as spectators, but as explorers. One of the earliest was the photographer Félix Nadar, who, in 1861, used primitive lighting methods to capture ghostly images deep beneath the city. These photographs were revolutionary, not just for their technical merit but for their eerie atmosphere. Nadar’s work revealed the Catacombs as a space worthy of aesthetic contemplation, not merely historical interest.

More recent artists have taken a riskier path. Known as “cataphiles,” these underground explorers create art in unauthorized zones. Parisian graffiti artists such as Psyckoze Nolimit have painted elaborate murals, sculptures, and typographic installations in hidden chambers. While much of this work is impermanent, some pieces have survived for decades, passed from one generation of cataphiles to the next.

The Legal and Ethical Maze

Creating art in the Catacombs without permission is illegal, punishable by fines and arrests. Yet for some artists, the risk is part of the allure. It brings urgency and rebellion to their work, connecting them to a lineage of countercultural expression. These acts defy not just the law, but traditional notions of what constitutes a gallery or studio.

Some argue this art desecrates a sacred site, while others see it as a continuation of the Catacombs’ legacy as a mirror of society. The question is whether intention redeems intrusion. Like much of modern art, the answer depends on context. But one thing is certain: the Catacombs continue to inspire the boldest among us to find beauty even in the depths of death.

The Cataphile Subculture and DIY Aesthetics

The modern cataphile movement, emerging in earnest during the late 20th century, transformed the Paris Catacombs from a historical artifact into a living underground community. These urban explorers—often artists, punks, or philosophical anarchists—illegally access restricted parts of the Catacombs. Motivated by curiosity and creativity, they map forgotten tunnels, host underground film screenings, and create ephemeral art installations. Though largely invisible to the surface world, cataphiles have developed their own visual language and aesthetic codes.

This underground world has produced its own form of DIY art, born of rebellion and necessity. Paint, candles, broken tiles, and even human bones are repurposed as materials. The fragility and impermanence of these works—constantly at risk from collapse, discovery, or time—contribute to their raw emotional impact. It’s a kind of guerrilla artistry that rejects commercialization, echoing older traditions of sacred space and hidden messages.

A Culture Beneath the Surface

Cataphile culture is influenced by punk, libertarian, and anti-globalist movements that emerged in France during the 1970s and 1980s. It carries the spirit of resistance and counter-authority, celebrating spaces unclaimed by the state. Their work is rarely signed, and anonymity is a core value, reinforcing the idea that the art belongs to the community, not to individual fame. Despite the legal risks, many cataphiles view their actions as a form of preservation—keeping the Catacombs alive as a space of living memory, not sterile museum curation.

Photographers and documentarians have attempted to catalog these elusive works, but their efforts are often incomplete or quickly outdated. Some projects, like the 2004 discovery of an entire underground cinema set up by cataphiles (complete with electricity and a bar), shocked authorities and fascinated the public. The Catacombs have become, for these creators, both canvas and sanctuary. This makes their subculture one of the most important and least visible contributors to the modern artistic legacy of subterranean Paris.

Comparative Spaces: Other Ossuaries and Their Artistic Impact

While the Paris Catacombs are singular in scale and cultural influence, they are not the only ossuary to fuse death and design. The Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic is perhaps the most famous alternative, housing the bones of over 40,000 people arranged in chandeliers, pyramids, and coats of arms. Created in the 1870s by František Rint, a woodcarver commissioned by the Schwarzenberg family, this chapel transforms human remains into baroque spectacle. It offers a more ornamental, even theatrical, approach to confronting mortality.

In Italy, the Capuchin Crypt beneath the Santa Maria della Concezione church in Rome contains the bones of around 4,000 friars, arranged in arches and niches since the 17th century. The intention here is deeply religious—the Capuchins believed that their macabre décor reminded viewers of the Christian promise of resurrection. Latin inscriptions warn against vanity and pride, reinforcing traditional Catholic teachings. This blend of spirituality and artistry mirrors the values of the Counter-Reformation era.

Other Global Catacombs and Cultural Comparisons

Palermo’s Catacombs of the Capuchins take the relationship between death and display to another level. Here, corpses are not simply arranged bones but preserved bodies dressed in their finest clothing. The most famous is little Rosalia Lombardo, who died in 1920 at age two and was embalmed so perfectly that she appears to be merely sleeping. Her presence in the catacombs offers a hauntingly intimate confrontation with death, quite different from the more abstract symbolism of Paris.

What sets the Paris Catacombs apart is their understated, philosophical aesthetic. Where Sedlec dazzles and Palermo shocks, Paris broods. The Catacombs reflect Enlightenment ideals of order, reason, and contemplation—even in death. They are less about spectacle and more about the sobering truth of mortality, making them perhaps the most artistically mature and emotionally resonant of the world’s ossuaries.

Ethical Debates: Is This Art or Desecration?

One of the most enduring controversies surrounding the Paris Catacombs is whether artistic intervention in the space is a form of expression or a moral transgression. Critics argue that creating art, hosting parties, or installing sculptures in a mass grave disrespects the dead. These bones once belonged to real individuals—mothers, fathers, children—each with a story now lost to time. Treating them as aesthetic elements can strike some as exploitative or sacrilegious.

However, others defend these artistic acts as forms of remembrance and reflection. In a secularizing society, traditional modes of mourning and veneration have weakened. Art becomes a new language through which people confront death, honor the past, and question their place in history. Especially when done respectfully, these acts can breathe new relevance into an ancient site, ensuring that the memory of those interred is not forgotten.

Voices from Faith and Government

Religious leaders often weigh in on the ethics of art in the Catacombs, usually from a standpoint of reverence and caution. Some Catholic figures in France have condemned unsanctioned activity in the tunnels, citing the dignity of the human body and the need for solemnity. Meanwhile, the French government tightly regulates access to the Catacombs, and defacing or entering restricted sections carries fines or even jail time. Legal boundaries exist to preserve the sanctity and historical integrity of the site.

Still, ethical lines remain blurry. Is it more disrespectful to create art in the Catacombs—or to turn them into a tourist attraction, commodified for Instagram photos and souvenir stands? These are not easy questions. But the fact that they are asked at all underscores the unique power of the Catacombs as a space where art, death, and morality collide. It’s a debate that will likely continue as long as the Catacombs endure.

Conclusion: A Labyrinth of Memory, Death, and Art

The Paris Catacombs are not just a graveyard—they are a cultural monument, a philosophical space, and a source of endless artistic inspiration. Their walls whisper not just of death, but of meaning—of how we, as individuals and as societies, confront the inevitable. From the Enlightenment thinkers who envisioned an orderly repository of bones to the cataphile graffiti artist scrawling messages in a hidden chamber, each has left their mark on this subterranean world. They remind us that beauty and terror often walk hand in hand.

For artists, the Catacombs offer more than just aesthetic challenge—they demand emotional honesty. Here, one cannot escape the truth of mortality. Every installation, every photograph, every whispered ghost story is layered over a foundation of real human lives. It is a space where creation and destruction are not opposites but partners in a quiet, eternal dance.

Final Reflection and Responsibility

As visitors or interpreters of this unique space, we carry a responsibility. Whether we explore the Catacombs in person or through the pages of a book or the frame of a painting, we become participants in their legacy. Our fascination must be balanced with reverence. This is a site of death, yes—but also of extraordinary life, channeled through art, design, and storytelling.

The Catacombs stand as one of humanity’s most profound cultural expressions—a literal descent into the past. And as long as their tunnels remain, filled with bones and meaning, they will continue to draw artists, thinkers, and dreamers into their depths. Just as they always have.

Key Takeaways

- The Paris Catacombs serve as both a memorial and a creative canvas.

- Their architecture reveals artistic intent through symmetry and symbolism.

- Ghost stories and legends keep the Catacombs culturally alive.

- Modern artists and cataphiles reinterpret the space with underground art.

- Ethical debates persist around the line between reverence and exploitation.

FAQs

- What are the most famous legends tied to the Paris Catacombs?

The story of Philibert Aspairt, ghost sightings, and lost explorers are among the most retold tales. - Is it legal to create art in the Catacombs?

No—any unsanctioned activity in the restricted zones is illegal and punishable by fines. - How do artists incorporate catacomb imagery into their work?

Through photography, street art, installations, and themes in literature and film. - Are there other ossuaries similar to the Paris Catacombs?

Yes—Sedlec in the Czech Republic, Palermo in Italy, and the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. - Why are the Catacombs considered important in French visual culture?

They embody themes of mortality, order, and spiritual reflection central to French art.