A city’s aesthetic often reveals itself not in grand pronouncements but in the grain of its streets, the habits of its facades, and the density of its symbols. Prague, more than most cities, compels its visitors to look upward and inward at once. It is a place where the decorative speaks with architectural weight, and the stones themselves seem to carry memory. Before the Gothic heights of St. Vitus or the nervous ingenuity of Czech Cubism, Prague was already an artistic organism in formation—stitched together by myth, regional power, and the improvisational pragmatism of empire.

The Vltava as Muse and Boundary

The Vltava River, winding through the city like a drawn bow, is both lifeline and limit. Ancient settlements clustered on opposite banks—the Castle District on one side, the Old Town and later New Town on the other—long before the city coalesced into a single urban identity. The river not only framed the city’s geography but shaped its visual logic. Its crossings—most famously the Charles Bridge—became processional stages and symbolic arteries, where political theology and urban planning blurred.

The earliest art in Prague was functional but suggestive. Romanesque rotundas, such as St. Martin’s at Vyšehrad, spoke of a religious architecture still emerging from monastic austerity. They were thick-walled, low-ceilinged, and sparsely decorated, more statements of possession and survival than aesthetic invention. But even these early forms carried visual codes: blind arcading, carved tympanums, and imported motifs gestured toward the Latin West and the ambitions of a region angling for inclusion in the broader Christian world.

Romanesque Stone and Bohemian Ambition

In the 11th and 12th centuries, as Bohemia asserted itself within the political machinery of the Holy Roman Empire, Prague’s art began to serve as a language of power. The Romanesque style, imported from southern Germany and northern Italy, was adapted to local material and spiritual needs. The Basilica of St. George, with its austere rhythm of columns and apses, became not just a church but an ideological marker—evidence of dynastic consolidation and clerical infrastructure. Art was not merely devotional; it was administrative, hierarchical, and strategic.

Sculpture, when it appeared, did so tentatively. Capitals might be adorned with animals or biblical scenes, but the Czech stoneworker still stood in the shadow of foreign models. Yet this very restraint, this slightly delayed absorption of Western currents, would become a strength. Prague did not rush to innovate; it watched, absorbed, and then reinterpreted. This became a recurring pattern—one that would later allow it to develop truly original hybrids, such as Cubist architecture or the Art Nouveau synthesis of folk and modern motifs.

Meanwhile, manuscript illumination thrived behind cloister walls. The Vyšehrad Codex, a late 11th-century gospel book, reveals a culture not only borrowing but embellishing the Ottonian visual lexicon. Golden backgrounds, twisted vine motifs, and a dense narrative compression all point to an elite comfortable in both word and image. The Bohemian court understood the symbolic weight of visual literacy.

Myths, Saints, and the Visual Invention of a Capital

Just as vital as stone and parchment, however, was story. Prague’s visual identity was always more than architectural—it was mythopoeic. The legends of Libuše, Přemysl the Ploughman, and St. Wenceslas functioned as narrative anchors for spatial memory. The visual representations of these stories—on fresco, tapestry, and eventually in public sculpture—worked to sacralize the city’s topography.

Take the figure of St. Wenceslas, the “Good King” of carol and cult. His equestrian image, which would become a monumental centerpiece in Wenceslas Square centuries later, originated in manuscript marginalia and processional banners. Early visual depictions of Wenceslas—bearded, youthful, haloed—set the template for a saint who was as much symbol as intercessor. His story was told again and again not only to affirm Christian piety, but to map a specifically Czech sanctity onto the city itself.

Even Libuše, the mythical prophetess who is said to have founded Prague with a vision from her cliffside throne, had an iconographic presence. Though initially passed down orally, by the time of the 14th century chroniclers, she appeared in murals and allegorical cycles—always portrayed as wise, commanding, and linked to landscape. Her image made political geography into fate. The hills she pointed toward became the hills on which castles were built.

These legends were not quaint embellishments. They offered a visual grammar for the emergent city. In altarpieces, civic seals, and tapestries, Prague was rendered as both historical and providential—chosen, elevated, and charged with meaning.

By the late 13th century, Prague stood poised for transformation. The medieval city, still provincial in parts, was about to become an imperial capital. Charles IV would soon remake its skyline, calling artists and architects from across Europe, and endowing the city with a grandeur few could match. But that later radiance was built on deeper foundations: a river that shaped the streets, a stone that spoke the politics of faith, and a mythology that taught Prague how to see itself. Even in its earliest forms, Prague’s art was already doing what it would do for centuries—layering history into beauty, and beauty into memory.

Gothic Prague: Faith, Verticality, and Visual Drama

It begins with a vault and a vision—stone ascending in counterpoint to gravity, and a city recast in height. Gothic architecture arrived in Prague not as mere style but as imperial declaration. Under the rule of Charles IV, Prague became a spiritual and administrative nerve center for Central Europe, and its visual culture was radically transformed. What had been sturdy and earthbound became intricate, theatrical, and celestial. In the 14th century, Prague’s ambition crystallized in the pointed arch and flying buttress, and the city’s skyline began to express a theology of dominance.

Charles IV’s Imperial Aesthetic Project

The driving force behind Prague’s Gothic flourishing was Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia. His reign (1346–1378) marked a turning point not only politically but artistically. Charles viewed art and architecture as extensions of authority—tools of persuasion, devotion, and legacy. His urban interventions were systematic: the founding of the New Town (Nové Město), the reconstruction of Prague Castle, and the reorganization of religious life through new monastic foundations and cathedral projects.

Charles envisioned Prague as a Second Rome. This was not metaphor but policy. He imported relics, established Prague as an archbishopric, and founded the first university in Central Europe in 1348. Each of these moves required visual framing: chapels, facades, reliquaries, ceremonial sculpture. He called in artists and architects from France and Germany, most notably the Bavarian-born Peter Parler, whose work would define Gothic Prague as distinctly Bohemian.

In this new Gothic idiom, Charles encoded his lineage, his ambitions, and his spiritual metaphysics. The city became a visual catechism—its stonework narrating sacred history, imperial genealogy, and apocalyptic symbolism. This was not only art in service of faith, but faith in service of monarchy.

St. Vitus Cathedral and the Politics of Stone

Nowhere is Charles’s vision more visible than in St. Vitus Cathedral. Construction began in 1344 under Matthias of Arras, a French master builder who brought the linear rigor of the Southern Gothic. But it was Peter Parler who transformed the structure into something more dynamic, more sculptural, more psychologically alive.

Parler’s contribution was as much spatial as ornamental. He loosened the geometry of the choir vaults, introducing asymmetries and net-like ribs that created a sense of unfolding energy. His treatment of tracery and clerestory windows allowed for greater light modulation—so that the divine did not merely dwell in the cathedral but moved within it.

The cathedral was a palimpsest of sacred and dynastic purpose. Beneath its high Gothic arches lay the tombs of Bohemian kings, while its chapels housed relics of saints acquired from across Christendom. Most famously, the Chapel of St. Wenceslas—encrusted with semi-precious stones and frescoed with legends—functioned as both reliquary and political shrine. Here, the Czech patron saint was not only venerated but positioned as spiritual guarantor of Charles’s rule.

Three particularly unusual features of the cathedral reveal the Bohemian adaptation of Gothic norms:

- The use of life-sized sculptural busts—often thought to be portraits of Parler’s workers—lining the triforium, breaking with anonymous medieval traditions.

- The unconventional articulation of the southern tower, whose late completion left a hybrid spire that bridged Gothic with Renaissance and Baroque layers.

- The astronomical clockworks and calendrical motifs embedded in architectural detail, reflecting Prague’s courtly interest in cosmology and timekeeping.

St. Vitus was not completed until the 20th century, but its 14th-century foundations cemented Prague’s status as a city where faith, art, and governance fused into a single architectural lexicon.

Sculpture, Manuscript, and the Holy Roman Gaze

Gothic sculpture in Prague evolved alongside the architecture, but often played a quieter, more contemplative role. Unlike the dramatic façades of Reims or Chartres, Prague’s public sculpture tended toward the restrained. The figures carved by Parler’s workshop—whether angels or prophets—are distinguished by their individualized faces, dynamic postures, and inward gaze. They seem less theatrical than meditative, often inhabiting a liminal space between worldliness and beatitude.

This emotional realism carried into the smaller arts as well. Illuminated manuscripts produced at Charles’s court, such as the famed Vyšehrad Antiphonary or the Bible of King Wenceslas, display a rich visual language: elongated saints, gold-leaf ornamentation, and architectural frames that echo the vaults of St. Vitus. But beneath the ornament lies a deeper register of affect—martyrs who wince, apostles who lean inward in whispered counsel, a Christ whose glance is both judgment and mercy.

The spiritual intensity of these images may have reflected a broader cultural anxiety. The 14th century in Prague was marked not only by imperial expansion but by plague, succession crises, and religious unrest. The arts responded with both splendor and introspection, producing images that shimmered on the surface but suggested a world beneath trembling with tension.

And yet, for all its sacred focus, Gothic Prague was never insular. Pilgrims and emissaries traveled to and from the city; artists saw Paris, Cologne, Siena. The Holy Roman gaze—that visual sensibility forged in a polyglot empire—was always looking both outward and inward. Prague’s Gothic art navigated this gaze with remarkable poise, absorbing outside influences while forging a visual identity steeped in Bohemian particularity.

By the time of Charles IV’s death, Prague had become an artistic capital—dense with chapels, stained glass, codices, and sculpture. But his monumental vision would soon encounter turbulence. The Hussite Wars would erupt in the early 15th century, ushering in an era of iconoclasm, reform, and uncertainty. The city’s religious art would become both target and battleground. But the vertical lines of the Gothic period—their aspiration, their psychological depth, their theological stakes—would remain etched in the city’s memory and silhouette.

The Bohemian Renaissance: Humanism and Ornament

At first glance, the Renaissance arrived late in Prague. By the time Italian humanists were charting anatomical precision and rediscovering Vitruvius, Bohemia was still reeling from religious wars and political fragmentation. But once the dust of the Hussite uprisings settled, Prague entered a quieter period of renewal—one defined not by explosive innovation, but by selective adaptation and careful synthesis. Here, Renaissance ideals were filtered through Bohemian sensibilities: the ornamental over the austere, the emblematic over the systematic, and the courtly over the civic. The result was a form of visual humanism rooted not in rebellion, but in refinement.

Italian Artists in a Northern Court

The first stirrings of Renaissance influence in Prague came not from local revolutionaries but from royal taste. After the extinction of the Luxembourg dynasty, the Bohemian crown passed into the hands of the Jagiellonian line, whose rule from the late 15th to early 16th century ushered in an era of relative peace and cautious prosperity. Wladislaus II (r. 1471–1516) moved the royal residence permanently to Prague Castle, making the court once again a cultural magnet.

Italian artists and architects soon followed, drawn by patronage and prestige. Benedikt Rejt, a Czech-born architect trained in German Late Gothic but influenced by Italian forms, became one of the era’s defining figures. His work on Vladislav Hall within Prague Castle shows this transitional moment clearly. The hall’s ceiling features a vast network of ribbed vaults—still Gothic in spirit—but their sweeping, geometric regularity hints at Renaissance spatial thinking. This was a court architecture that paid homage to the past while rehearsing the future.

Italian sculptors, such as Paolo della Stella and Giovanni Maria Aostalli, contributed to funerary monuments, fountains, and portals throughout the city. Their style was classical, but not archaizing. The human figure, increasingly central, appeared with a softened sensuality and a hint of theatrical poise. These were bodies meant not for martyrdom but for memory.

Three aesthetic tendencies marked the Prague Renaissance:

- A fascination with surface detail: sgraffito facades, coffered ceilings, and stucco flourishes proliferated in noble residences and public buildings.

- A hybridization of styles: Gothic ribbing coexisted with pilasters and arches in the same structure, often without clear hierarchy.

- A visual interest in allegory and emblems: coats of arms, zodiac signs, and mythological motifs reappeared, not merely decorative, but as coded symbols of virtue, lineage, and cosmology.

This was not the Florence of the Medici or the scientific spirit of Leonardo—it was a more modest, more ornamental Renaissance, but no less deliberate.

The Arcades of Belvedere and the Geometry of Grace

Nowhere does Bohemia’s Renaissance elegance declare itself more clearly than in the Queen Anne’s Summer Palace—also known as the Belvedere—commissioned by Ferdinand I for his wife Anne of Bohemia and Hungary. Designed by Italian architects and constructed from 1538 to 1563, the Belvedere is an architectural anomaly in Prague: a freestanding villa in the classical style, set apart from the city’s medieval fabric, like an imported dream.

Its defining feature is its arcade—a series of slim, Ionic columns supporting a delicate roofline, framing views of the castle gardens and the horizon beyond. The structure is symmetrical, restrained, and serenely horizontal. But it is not minimalist. Every surface is animated with sgraffito decoration—mythical creatures, garlands, Latin inscriptions—giving the viewer a sense of both intellectual play and regal self-assurance.

The Belvedere was less a residence than a stage for ideas. It was where music, astronomy, and diplomatic ceremony coexisted under classical ideals of order and proportion. The adjacent Singing Fountain, cast in bronze with ornate bas-relief panels, turned water into choreography. The entire complex suggested a new kind of space: one where reason, pleasure, and statecraft might merge.

For Prague’s artists and architects, the Belvedere became a visual grammar book. Its columns and patterns were copied in noble estates, civic buildings, and even tombstones. But few could match its coherence. It remained a singular object of aspiration—a monument to the city’s cosmopolitan potential.

Royal Portraits, Alchemy, and Self-Invention

While architecture flirted with classical restraint, painting during the Prague Renaissance moved more cautiously. Gothic devotional styles persisted into the 16th century, particularly in ecclesiastical commissions. But portraiture became a key site of innovation, driven largely by the court’s interest in identity, legitimacy, and science.

The royal portrait in Prague was not simply likeness—it was emblematic self-fashioning. Painters such as Jacob Seisenegger and later Bartholomeus Spranger captured rulers and aristocrats with the trappings of virtue, learning, and lineage. Books, globes, armor, and astronomical instruments often appeared alongside the sitter. These were not props but signals: a visual rhetoric of governance grounded in Renaissance ideals of reason and order.

There was also an esoteric dimension. Alchemy—both as science and metaphor—played a significant role at court, especially as Prague approached the reign of Rudolf II (whose obsession would define the next chapter). Even before his arrival, artists embedded alchemical references into their compositions: ouroboros rings, planetary metals, symbolic animals. These motifs linked the arts to the occult sciences, blurring the line between image and invocation.

One remarkable example is the evolving image of the Bohemian crown itself. No longer simply a relic of feudal inheritance, it was depicted as a cosmological object—radiant, symmetrical, mathematically perfect. Renaissance art in Prague may not have produced a Michelangelo, but it offered something more elusive: a vision of art as mirror, map, and mechanism.

By the end of the 16th century, Prague stood on the cusp of another transformation. The sober elegance of the Renaissance would soon be overwhelmed by the strange fervor of Mannerism and the maximalist swirl of the Baroque. But in this middle moment, the city achieved a fragile balance—between north and south, ornament and intellect, myth and measure. It was not a rupture with the Gothic past, but a re-tuning of its emotional register: from penitential awe to humanistic poise. Prague, once a city of stone saints and apocalyptic visions, had learned to see itself in columns and arcades, portraits and allegories. The mirror had turned outward, and with it, a new self began to emerge.

Rudolfine Prague: Art, Science, and Obsession

It was a court at once glittering and opaque, rational and haunted. When Emperor Rudolf II moved his imperial seat from Vienna to Prague in 1583, the city transformed into one of the strangest and most compelling artistic laboratories of early modern Europe. No other monarch in the Habsburg world—and few in the history of European art—assembled a collection as eccentric, ambitious, and hermetic as Rudolf’s. His Prague became not only a haven for painters, sculptors, and architects, but for astrologers, alchemists, automatists, and scholars of the arcane. This was not the Renaissance of clarity and harmony, but of mirrors, mutations, and microscopic truths.

Emperor Rudolf II as Collector and Alchemist

Rudolf II ruled as Holy Roman Emperor from 1576 to 1612, but his reign is often remembered more for its cultural consequences than its political ones. Though he largely withdrew from military campaigns and Catholic re-consolidation efforts that dominated other Habsburg courts, Rudolf directed his energy inward—to art, science, and mysticism. In this inward turn, he fashioned himself not just as patron but as participant.

Prague Castle became a Wunderkammer on an imperial scale. Rudolf’s collection included antiquities, paintings, sculptures, botanical specimens, celestial globes, automatons, fossils, mechanical clocks, and alchemical devices. In a time when taxonomy was still an act of the imagination, the collection did not separate the natural from the supernatural. What mattered was rarity, resonance, and symbolic density.

He employed artists such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who painted his likeness as Vertumnus—the Roman god of change—composed entirely of fruits, vegetables, and flowers. This was no jest. It was a portrait of a ruler who saw himself as mutable, cosmic, and hybrid. The face that emerged from that impossible bouquet was not a satire but an emblem of imperial omniscience.

Rudolf’s obsession with alchemy was equally sincere. He corresponded with John Dee and Edward Kelley, sought out texts on the Philosopher’s Stone, and funded transmutation experiments. But unlike earlier rulers who dabbled in alchemy for practical gain, Rudolf saw it as an art form—akin to painting in its layering, secrecy, and transubstantiation. His court blurred categories on every level: king and mage, artist and scientist, image and instrument.

Arcimboldo, Roos, and the Culture of Cabinets

The Rudolfine style did not emerge from one school or workshop. It was a mood—baroque before the Baroque, surreal before Surrealism. Its aesthetic prized intricacy, obscurity, and intellectual wit. The artists who flourished in this context did so because they could speak multiple languages: classical, grotesque, hermetic, erotic.

Arcimboldo, the most emblematic of Rudolf’s painters, returned to Prague in the 1580s after working in Milan and Vienna. His composite heads—constructed from books, animals, and flora—were more than visual riddles. They embodied the emperor’s belief that the world was knowable through pattern, that the visible was a code. His Librarian (composed entirely of tomes and bookmarks) and Water (a face made of fish and eels) were not simply trompe l’œil; they were encyclopedias made flesh.

Another court artist, Roelant Savery, combined landscape painting with zoological exactitude. His renderings of dodos, exotic birds, and imaginary beasts expanded the imperial gaze beyond Europe, integrating natural discovery into aesthetic pleasure. In his canvases, paradise was catalogued—not as a fantasy, but as a possibility.

The emperor’s passion for assemblage found architectural expression in the vast Cabinet of Curiosities, or Kunstkammer, which filled entire wings of the palace. Here, a preserved chameleon might sit beside a lapis lazuli cup, a taxidermied bird next to a miniature clockwork ship. These were not objects of leisure. They were instruments of thinking—devices through which the emperor meditated on the order (and disorder) of the cosmos.

Three key characteristics defined the Rudolfine visual culture:

- An intense interest in micro-worlds: miniatures, magnification, and hidden compartments were everywhere.

- A collapse of boundaries between genres: portraits merged with allegory, science with fantasy.

- A coded eroticism: mythological nudes and disguised sexual symbolism appeared even in scientific illustrations.

For artists, this created unusual freedom—and unusual expectations. Works were meant to impress, but also to mystify. Rudolfine art was not meant to be understood at first glance. It was a puzzle handed from maker to monarch, decipherable only through shared allusion.

Astronomy, Eroticism, and the Prague Mannerist

Science in Rudolfine Prague was not yet specialized. Astronomy was still tangled with astrology, anatomy with mysticism. The emperor funded Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, both of whom lived and worked in Prague for periods of their careers. Kepler’s Rudolphine Tables—named in gratitude—represented a major advance in celestial computation, but even these tables carried an echo of divination. The cosmos was not just measured, but interpreted.

Artists absorbed this atmosphere. Their canvases, engravings, and reliefs teem with stars, moons, planetary deities, and anthropomorphic signs of the zodiac. The iconography of the heavens was not background decoration, but a structuring principle. Paintings were designed to reflect the harmonic proportions of the macrocosm, and portraits often contained celestial diagrams as markers of fate.

Eroticism, too, became cosmological. The female nude in Prague during this period was rarely idealized. Instead, she was enigmatic, frequently part of allegorical or astrological systems. Spranger’s Venus and Adonis or Hans von Aachen’s Allegory of Peace depict bodies that are both sensuous and strange—elongated, turned at impossible angles, draped in fabrics that seem to flow by their own volition. Mannerism, the dominant style of the era, delighted in the theatrical: it prized the elegant distortion, the delayed revelation.

These images, dense with symbols and charged with erotic ambiguity, did not offer clarity. They were invitations to interpretation. They mirrored the court’s philosophical obsession with concealment, transformation, and layered meaning.

By the time of Rudolf’s death in 1612, the imperial court in Prague had already begun to unravel. His brother Matthias relocated the seat back to Vienna. Many of the artists and scientists dispersed. The Thirty Years’ War would soon ravage Bohemia, and large parts of Rudolf’s collection were looted or dispersed. Yet the impact of his court lingered—in the archives of European museums, in the histories of science, and most visibly, in the city of Prague itself.

Rudolfine Prague was never truly a Renaissance court, nor a Baroque one. It belonged to a narrower and stranger zone of cultural history: an empire turned inward, a ruler obsessed with the invisible, and a city transformed into a cabinet of thought. Its art continues to whisper, if not always clearly, because it was made to seduce not with answers, but with questions.

Baroque Conversions: The Jesuit Agenda and Czech Resistance

In the aftermath of war, Prague’s art spoke in a new register—one of thunderous faith, heightened drama, and ideological confrontation. The early 17th century saw Bohemia convulsed by the Thirty Years’ War, a conflict rooted in religion but unfolding across political and cultural lines. The Bohemian Revolt of 1618 and the catastrophic defeat at the Battle of White Mountain two years later marked not just a political turning point, but a profound visual reprogramming of Prague itself. Where Rudolfine art had been ambiguous and speculative, Baroque art declared, instructed, and dazzled. It was an art of victory—and of occupation.

Theatricality on the Streets and Altars

The Catholic victory at White Mountain in 1620 allowed the Habsburgs to reassert control over Bohemia with ruthless efficiency. Protestant nobles were executed, churches were re-catholicized, and Czech-language liturgy was suppressed. But this re-imposition of Catholicism was not just political—it was visual. Art became the primary vehicle of persuasion, and Prague’s cityscape was rapidly remade to reflect a new orthodoxy.

The Jesuit order, newly empowered in Bohemia, led much of this cultural campaign. Their agenda was clear: to reclaim not just churches, but the hearts and eyes of the populace. To do so, they harnessed the full range of Baroque theatricality—ceiling frescoes that tore open heaven, altars that overflowed with gold and blood, sculptures that lunged into the viewer’s space with outstretched hands and draped robes.

St. Nicholas Church in the Lesser Town, constructed beginning in 1704 by Christoph Dientzenhofer and completed by his son Kilian Ignaz, is one of Prague’s most overwhelming examples. Its interior is a cascade of pink marble, gilded ornament, and soaring frescoes that celebrate the triumph of the Church Militant. The dome—an illusionistic marvel painted by Johann Kracker—features a dizzying vision of the Trinity presiding over a cloud-swarmed choir of saints. This was art as sermon, art as spectacle, art as conquest.

Even the streets became processional stages. Statues of saints appeared on bridges and squares—most famously, the Charles Bridge, now lined with 30 stone figures of martyrdom and miracle. These sculptures were not contemplative; they were demonstrative. They reached outward, gestured skyward, called for allegiance.

Three visual strategies defined Prague’s Baroque mode:

- The use of diagonals and spirals to suggest movement and emotion.

- A theatrical dialogue between light and darkness—windows placed to ignite gold leaf and cast deep shadows.

- The mobilization of sculpture as part of architectural rhythm, creating buildings that seemed to breathe or pray.

Baroque Prague, in short, was not built to charm—it was built to convince.

The Kinský Palace and the Language of Power

Beyond churches and bridges, Baroque art also infiltrated the civic and domestic sphere. Aristocratic families, many of whom had aligned themselves with the Habsburgs after the war, commissioned grand palaces in the New Town and Old Town. These buildings often featured monumental facades, sculpted pediments, and allegorical frescoes that announced both wealth and loyalty.

The Kinský Palace, on Old Town Square, is a prime example. Built in the mid-18th century, it blends Rococo elegance with Baroque assertiveness. Its undulating facade, sculpted balconies, and statuary of classical deities signal the fusion of secular power and cultural display. Inside, ceiling paintings by Josef Navrátil celebrate Apollo, the Muses, and Enlightenment virtues—but within a Catholic, monarchical frame.

These palaces were more than residences. They were ideological outposts. Their decoration was loaded with coded messages: portraits of emperors, symbols of divine order, and carefully arranged genealogical frescoes. Even the gardens were sculpted into stage sets, with grottoes, obelisks, and symmetrical paths that reinforced the idea of centralized, God-given control.

Yet beneath the polish, there was unease. Many of the noble families whose homes now gleamed with imperial favor had once been Protestant. Their conversions, their newly acquired lands, and their baroque splendor were built on the ruins of a different Prague—a Prague silenced, but not entirely erased.

Faith, Spectacle, and the Counter-Reformation Image

The defining artistic current of this period was the Counter-Reformation, and Prague became a textbook case of its strategy. Art was not to inspire ambiguity or reflection; it was to affirm doctrine and stir the senses. This imperative shaped not only architecture and sculpture, but painting and print.

One of the most powerful examples is the cult of St. John of Nepomuk. Canonized in 1729, he became a kind of visual patron saint of Prague. His martyrdom—cast into the Vltava by King Wenceslas IV for refusing to betray the queen’s confessional secrets—was dramatized again and again in sculpture, painting, and print. His most famous image stands on the Charles Bridge: a baroque bronze statue by Matthias Braun, showing the saint mid-fall, five stars circling his head.

Nepomuk’s story was ideal for the Counter-Reformation: a saint loyal to the seal of confession, resisting a secular authority. He became an icon of fidelity and obedience, and his likeness spread across the city—and the entire Habsburg empire—with astonishing speed. Every church had its Nepomuk. His face appeared on medals, processional banners, and reliquaries. His story became part of the visual rhythm of Catholic restoration.

Yet Prague’s Baroque culture was not without contradiction. In private, Czech elites continued to commission allegorical paintings and rococo interiors that leaned more toward sensuality than piety. The line between sacred and profane blurred in the hands of painters like Petr Brandl, whose altarpieces are marked by Caravaggesque chiaroscuro and turbulent emotion. His saints weep, bleed, and reach—not from serenity, but from a storm of human feeling.

And still, Czech language and identity survived in private chapbooks, folk crafts, and oral tradition. The Baroque image may have sought to erase the Protestant past, but it could not fully suppress the undercurrents of resistance. In fact, it sometimes amplified them, simply by being so insistent.

By the mid-18th century, the Baroque tide in Prague had begun to ebb. Enlightenment values, economic modernization, and the rise of secular aesthetics were reshaping the city’s cultural terrain. But the Jesuit architecture, the gilded pulpits, the statue-lined bridges—all remained. Baroque Prague had succeeded in branding the city with a visual theology of triumph and transformation. It wrapped faith in gold, made politics into processions, and recast the city itself as a stage for salvation.

And yet, under that splendor, something restless remained. The Czech language had been pushed into the margins. The Protestant past had been paved over. The Baroque had conquered—but it had not quite silenced. That tension would begin to stir again in the next century, when artists, writers, and architects sought to recover what had been driven underground.

Rococo and Rationalism: Prague Between Ornament and Reform

In the decades following the Baroque’s grand pageantry, Prague entered a more delicate and ambiguous phase—one in which the power of ornament began to soften, and a quieter, more introspective aesthetic emerged. The Rococo in Prague did not sweep away the Baroque’s foundations; it hovered atop them like mist, reshaping their mass into lightness, intimacy, and wit. At the same time, the Enlightenment arrived—not as revolution, but as reform. What followed was a period of aesthetic negotiation, in which pleasure, reason, and piety vied for space on the same ceiling.

The Intimacy of the Decorative Wall

Unlike the theatrical excesses of high Baroque churches, Rococo interiors in Prague turned their attention inward. Their scale was often smaller, their effects more tactile. Instead of golden floods of divine glory, one now found playful stucco garlands, asymmetrical flourishes, and scenes of myth or pastoral leisure. This was an art of salons, not sanctuaries—an aesthetic better suited to aristocratic apartments than cathedral naves.

The Clam-Gallas Palace provides one of Prague’s most exquisite Rococo environments. While its exterior remains relatively sober, its interiors burst with delicate moldings, ceiling paintings, and gilded mirrors that refract light into shifting patterns. Here, art becomes environmental—meant to be lived with, moved through, glanced at in conversation. Scenes from classical mythology play across oval medallions: Venus lounging with doves, Cupid alighting on a cloud. These are not images of cosmic destiny, but of choreographed seduction.

This shift toward the decorative paralleled changes in social life. The salon culture that developed in Prague’s upper circles during the mid-18th century mirrored developments in Paris and Vienna. Conversations turned toward philosophy, literature, and science, and the art around them followed suit. It became more intimate, more ironic, more aware of the audience’s gaze.

Three subtle but significant features distinguished Prague’s Rococo:

- A fondness for pastel tones—soft greens, rose pinks, and creams that blurred the edges of form.

- A focus on surface continuity: stucco and paint merged, walls became visual tapestries.

- A displacement of the sacred: secular themes—pastoral scenes, classical myths, erotic play—entered spaces once reserved for devotional art.

In this context, Prague’s art seemed to exhale after the weight of the Counter-Reformation. It did not reject piety, but it relocated the divine into the folds of everyday beauty.

Enlightenment Eyes in a Catholic Frame

Alongside the Rococo’s ornamental pleasures, Enlightenment ideas began to reshape the city’s intellectual infrastructure. Reforms under Empress Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II touched nearly every aspect of cultural life—from censorship and clerical authority to education and urban planning. Art, long a tool of spiritual persuasion, was now tasked with reflecting clarity, usefulness, and decorum.

The Jesuits, once the dominant force in Czech visual culture, were suppressed in 1773. Their schools and churches remained, but their political grip dissolved. New state-sponsored academies promoted classical ideals over theological grandeur. Neoclassicism began to take root, not yet as dominant form, but as a conceptual horizon.

Artists such as Josef Bergler the Elder, who would later become the first director of the Prague Academy of Fine Arts (founded in 1799), navigated this transition with elegance. His work retained Baroque technical skill, but turned toward Enlightenment themes: civic virtue, historical allegory, and human reason.

Scientific illustration also came into its own. Botanical prints, anatomical studies, and mineralogical diagrams became prized both for their accuracy and aesthetic appeal. These were not dry technical exercises—they were images of order, clarity, and control, infused with a new reverence for the observable world.

This intersection of beauty and knowledge produced unexpected hybrids:

- Illustrated herbaria that married plant taxonomy with Rococo layout.

- Educational frescoes in gymnasiums that depicted allegories of physics, geometry, and the liberal arts.

- Public monuments that celebrated scientific figures alongside saints and emperors.

The result was an art that increasingly addressed the citizen rather than the subject. It sought not to convert but to elevate—to guide the viewer toward improvement through clarity and grace.

Public Sculptures and the Grammar of the Pastoral

Even as Rococo interiors embraced intimacy and Enlightenment paintings aimed for intellectual uplift, Prague’s public sculptures continued to play a central role in shaping collective identity. But here, too, the mood shifted. The violent martyrdoms of the Baroque gave way to calmer, often Arcadian imagery. Fountains, squares, and gardens were adorned with nymphs, muses, shepherds, and personifications of seasons or virtues.

The Vrtba Garden, laid out in the early 18th century on the slopes of Petřín Hill, stands as a masterwork of this transitional idiom. Its terraces, staircases, and balustrades are ornamented with statues by Matyáš Bernard Braun—figures whose poses are elegant, even flirtatious. They inhabit a world where mythology serves not as cosmic allegory, but as refined decoration.

Braun’s other major project, the allegorical statues in the Hospital Kuks complex, reflect a deeper tension. There, he carved figures representing virtues and vices—Justice, Lust, Humility, Envy—each rendered with psychological subtlety and theatrical flair. While nominally Catholic in origin, these sculptures operate in a more humanist mode, inviting ethical reflection rather than devotional awe.

This move toward allegory and pastoral fantasy was not apolitical. In a society still shaped by Habsburg absolutism and the scars of religious suppression, the Rococo and Enlightenment modes offered a space for coded commentary. Bucolic scenes could contain satire; classical myths could suggest contemporary anxieties. Art became quieter, but no less pointed.

By the close of the 18th century, Prague was poised for yet another cultural reinvention. The rise of nationalist sentiment, the revival of Czech language and folklore, and the growing desire for civic autonomy would all find their voice in the art of the 19th century. But the Rococo-Enlightenment period had done crucial work: it had softened the dogmas of the Baroque, infused art with reason, and expanded the range of what could be said—and seen—in Prague’s visual life.

The walls glittered, the ceilings smiled, and the city’s imagination began to widen its field. Ornament was no longer only divine; it had become intellectual. And in the process, the city took a breath before its next long cultural ascent.

National Revival and the Search for Czech Form

Beneath the elegant surface of Enlightenment Prague, something began to stir. A suppressed language, a scattered history, a longing for continuity—all these slowly gathered force in the 19th century as Prague entered its National Revival. This was not merely a literary or political movement; it was an aesthetic awakening. For the first time in centuries, art in Prague began to speak self-consciously in Czech again—not just linguistically, but visually. Artists, architects, and intellectuals sought to rediscover, invent, and define a national style that could reclaim the city from centuries of Habsburg rule and German dominance. The stakes were existential, and the canvas became a battleground for identity.

Folk Motifs and Political Allegory

One of the central strategies of the Czech National Revival was the elevation of folk culture to high art. What had once been relegated to embroidery, wooden toys, and peasant verse now became the foundation for a new visual language. Artists scoured the countryside for traditional costumes, architectural forms, and decorative patterns. These were not quaint gestures—they were defiant acts of cultural archaeology.

Painters such as Josef Mánes turned rural life into symbolic tableau. His portraits of Moravian girls in regional dress, his genre scenes of Slavic rituals, his calendar illustrations of peasant labors—all were composed with an eye toward dignity, rhythm, and mythic resonance. The rural Czech was no longer a subject of sociological curiosity; he and she became avatars of national soul.

Architecture followed suit. Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Gothic styles, though imported, were adapted to express national pride. The ornamentation on new buildings began to feature Czech coats of arms, historical scenes, and inscriptions in the Czech language—something unimaginable a generation earlier. The decorative became declarative.

These visual strategies were often wrapped in allegory. Paintings personified the Czech nation as a serene female figure, often veiled or mourning, recalling lost greatness or prophesying rebirth. In sculpture, figures of Hus, Comenius, and Saint Wenceslas were recontextualized not as mere saints or scholars, but as moral exemplars of Czech endurance.

Three elements recur across Revival-era art as talismans of Czech identity:

- The linden tree, national symbol of endurance and peace.

- The Hussite chalice, emblem of religious defiance and sovereignty.

- The Slavic color triad: red, white, and blue, encoded in costumes, banners, and decorative borders.

This wave of symbolic art was not abstract nationalism; it was materially specific, emotionally urgent. Artists were not just painting scenes—they were reasserting existence.

The National Theatre as Painted Manifesto

The National Theatre in Prague (Národní divadlo) became the spiritual and aesthetic epicenter of the Czech National Revival. Built with funds raised by public subscription, it opened in 1881 as a civic cathedral to art and language. Though damaged by fire soon after, it was rebuilt and reopened in 1883—this time more richly adorned, more self-consciously Czech.

The architecture, designed by Josef Zítek in a hybrid neo-Renaissance style, drew from Italian and French models but was filled with Czech content. Every surface of the theatre—inside and out—was used to narrate the nation’s story. Reliefs of mythic figures, busts of composers and poets, murals of historical allegories: this was Gesamtkunstwerk turned national curriculum.

The theatre’s interior painting program, led by Mánes, Mikoláš Aleš, František Ženíšek, and others, was effectively a manifesto. Ženíšek’s Apotheosis of the Czech Nation on the curtain shows a radiant female figure rising amid scenes of history, learning, and progress. Aleš’s murals in the foyer retell Czech legends with clear linework, dramatic composition, and a moral clarity that fused Neoclassicism with folk narrative.

This was art meant to educate as much as to enchant. Every detail—the typography of the programs, the choice of subject matter, the musical repertoire—was curated to reclaim and project Czech sovereignty through aesthetics. It was a theatre, yes—but also a visual constitution.

The theatre’s funding, drawn from peasants and industrialists alike, added another layer of meaning. It symbolized a united front of classes under a cultural ideal. Its architecture stood not just against the past but against invisibility.

Mánes, Aleš, and the Forge of Visual Patriotism

Josef Mánes (1820–1871) is often called the visual poet of the Czech National Revival, and rightly so. Educated in Prague and Munich, he was steeped in academic technique but driven by nationalist urgency. His work fused clarity of line with emotional tenderness, and his paintings often feel like carefully composed prayers—devotional not to saints, but to land and language.

His Calendar Plate cycle for the Prague Astronomical Clock remains one of the most beloved visual artifacts of the period. Each month is personified by a peasant engaged in seasonal labor—harvesting, pruning, sowing. The figures are monumental, yet humble. Their tools are rendered with the same care as their faces. Time itself becomes rural, cyclical, Czech.

Mikoláš Aleš (1852–1913), a generation younger, expanded this vision into larger and more explicitly political terrain. His illustrations for historical chronicles, posters, and architectural decoration bristle with energy. His style, sharp and linear, was suited to both didactic murals and mass-printed imagery. Aleš was a master of the visual slogan—able to condense centuries into a single emblem.

His collaboration with architects and builders ensured that Czech patriotism became embedded in the very stone and stucco of Prague. Schools, train stations, and apartment buildings bore his friezes and motifs. He made history public again—not in Latin inscriptions or courtly portraiture, but in common line and native tongue.

Together, Mánes and Aleš forged a visual language that merged folk authenticity with classical clarity. They gave form to the Czech longing for continuity—after centuries of suppression—and helped to reimagine Prague as a city that did not merely contain Czech culture, but expressed it.

By the dawn of the 20th century, the groundwork had been laid. Prague no longer borrowed its cultural self-understanding from Vienna or Rome. The National Revival had not only reclaimed the Czech past—it had built the aesthetic armature for the modern nation. In murals, facades, illustrations, and everyday design, a visual Czech was now visible.

The next artistic generation would take this foundation and push it further—not into nostalgia, but into innovation. Art Nouveau and Cubism awaited, eager to prove that Czech form was not only national, but modern.

Art Nouveau and the Prague Style: From Ornament to Identity

At the turn of the 20th century, Prague underwent a visual flowering that redefined both its urban fabric and its cultural self-image. Art Nouveau, known locally as Secese, arrived not as an imported fashion but as a vital articulation of modern Czech identity. It marked a turning away from historical pastiche and toward a synthesis of beauty, function, and symbolism. What made the Prague version of Art Nouveau distinctive was not simply its elegance, but its ideological charge: this was ornamentation as national expression, typography as protest, and architecture as embodied philosophy.

Alphonse Mucha and the Myth of the Slavic Soul

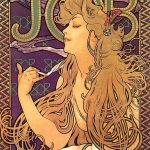

The most internationally recognized figure of this movement is Alphonse Mucha, whose lithographic posters for the actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1890s Paris became icons of Art Nouveau’s graphic vocabulary. Swirling lines, haloed figures, stylized flowers, and mystical inscriptions—it was a lexicon of spiritualized femininity and ornamental logic. But beneath its sensual allure was a political heart, one that would beat louder once Mucha returned to Prague.

Mucha’s later work, especially The Slav Epic, offers a different register: monumental canvases that depict key moments in Slavic history and myth with reverent solemnity. These paintings, completed between 1910 and 1928, blend Symbolist aesthetics with nationalistic pedagogy. Here, Mucha sought not only to beautify the past but to construct a visual history in which the Czech and broader Slavic identity was noble, unified, and spiritually radiant.

His figures are not individual portraits, but archetypes—priests, warriors, mourners, mothers—rendered in a soft-focus glow of faith and endurance. He used gold not for luxury, but for liturgical weight. In doing so, he reclaimed the scale of religious painting for secular and national myth.

While The Slav Epic was controversial for its didacticism, it encapsulated the Prague Art Nouveau ethos: the past reimagined through form, the national spirit rendered as decorative narrative.

Municipal House and the Total Artwork

Nowhere does Prague’s Art Nouveau achieve such a civic synthesis as in the Municipal House (Obecní dům), completed in 1912. Built on the former site of the Royal Court and designed by architects Antonín Balšánek and Osvald Polívka, the building is an encyclopedic example of Gesamtkunstwerk—a “total artwork” in which architecture, sculpture, mural, typography, lighting, and furniture function as a unified organism.

From the mosaic above the entrance—Homage to Prague by Karel Špillar, showing the city as a radiant matron offering sanctuary—to the interior stained glass, carved wood, wrought iron, and ornamental plaster, every detail is charged with symbolism. Czech myths, Slavic patterns, and local flora are woven into every surface. Even the fonts used in signage and menus were custom-designed to harmonize with the building’s nationalist elegance.

Inside, the Smetana Hall—a concert space crowned by a massive glass dome—is framed by murals from Mucha and other leading artists of the time. The themes vary: history, beauty, morality—but the undercurrent is consistent. This was a building designed to reflect a nation in waiting, on the edge of self-governance.

Municipal House was not merely decorative. It was also political. It hosted the 1918 proclamation of Czechoslovakia’s independence. In that moment, ornament ceased to be aesthetic garnish and became part of the architecture of statehood.

Three features distinguish Prague’s Art Nouveau architecture from its European counterparts:

- A persistent use of national allegory and local botanical motifs—lime leaves, thistles, and poppies—as structuring elements.

- A conscious integration of Slavic and folk styles into the refined vocabulary of the movement.

- A visual emphasis on synthesis: Prague Art Nouveau is less whimsical than its Parisian cousin, more architectonic, more symbolic.

Where French Art Nouveau evoked sensual reverie, Prague’s version often looked outward—toward history, myth, and collective identity.

Typography, Posters, and the Aesthetic of the Everyday

One of the most radical contributions of the Art Nouveau period in Prague was the aestheticization of the everyday. Under Mucha’s influence and the broader principles of the Secessionist movement, designers reimagined not only buildings and paintings, but menus, tickets, street signs, magazines, and advertisements. A nationalist modernity was to be visible everywhere—not in slogans, but in shapes and flourishes.

Typography became a central site of innovation. Czech typographers developed alphabets inspired by runic, Gothic, and folk elements. These were not academic exercises. They were meant to restore dignity to the Czech language in visual form. Street signage in Prague began to favor Czech over German, and in distinctly Czech lettering styles. The letter became a building block of identity.

Posters, too, became a kind of popular muralism. Commercial advertisements for theaters, products, and concerts borrowed from high art. Mucha’s influence was widespread, but local printers and illustrators adapted his style for a more pragmatic aesthetic—less mystical, more direct. The streets of Prague, in the early 1900s, shimmered with stylized women, looping tendrils, and nationalist color schemes.

Even industrial design was touched by the movement. Cutlery, tiles, lamps, and teapots from this period carry a soft geometry, a sinuous elegance that suggests domestic modernity without mechanization. This was not machine-age functionalism—it was a hopeful humanism in metal and glaze.

As Prague’s middle class grew, so did the demand for art that could live in homes, cafes, and public parks. Art Nouveau, in this sense, democratized design. It offered a vision of national beauty available in wallpaper and stained glass, in postage stamps and balconies.

By the eve of World War I, Prague’s Art Nouveau had accomplished something rare: it had made ornament speak. It had bound beauty to nationhood, myth to material, and turned a style into a declaration. But this stylistic high point also marked a threshold. The war would rupture the decorative optimism of the Secessionist age, and the architectural modernism that followed would reject much of Art Nouveau’s curvature and complexity.

And yet, the Prague style—shaped by Mucha’s mystical figures, the Municipal House’s grand synthesis, and the typographers’ visual patriotism—remains embedded in the city’s visual DNA. It did not just adorn Prague; it helped invent it.

Cubism in Stone: A Prague-Only Modernism

Among the many cities transformed by modernism in the early 20th century, only one took Cubism off the canvas and poured it into the street. Prague, alone in Europe, made Cubism architectural. While painters in Paris were fracturing planes and abandoning perspective on canvas, architects and designers in Bohemia took those same formal ideas and reimagined them in brick, stone, glass, and plaster. The result was not derivative, nor purely theoretical—it was a startling, concrete reinvention of space. Prague Cubism fused avant-garde aesthetics with structural ambition, and it remains one of the city’s most daring and enduring contributions to modern art.

From Paris to Vodičkova: Adapting the Grid

Czech artists were already well attuned to European artistic currents by the outbreak of World War I. In the first decade of the 20th century, Paris exerted enormous influence on Prague’s painters and writers. Picasso and Braque’s experiments with Cubism in Montmartre were quickly translated in the pages of Czech art journals and brought back by artists who studied abroad. But where French Cubism remained largely pictorial—concerned with how to see—Czech Cubism quickly became spatial: concerned with how to build.

The key figures in this transformation were Pavel Janák, Josef Gočár, and Josef Chochol—architects who moved from Secessionist elegance to something more aggressive, angular, and experimental. They began designing buildings in which the ornament was no longer applied, but integral to form. Cubist architecture was not decoration—it was faceting. A building’s surfaces were broken into crystalline geometries, windows set within sharply tilted planes, balconies and doorways fractured like cut gemstones.

This aesthetic took root in central Prague, particularly in the New Town (Nové Město), where bourgeois confidence and artistic daring converged. The House of the Black Madonna, designed by Josef Gočár in 1912, is often cited as the first true Cubist building in the world. Named after a baroque statuette preserved on its corner, the structure balances tradition and innovation. Its rusticated base gives way to a sharply articulated facade: angled bay windows, zigzag cornices, and dynamic ironwork. Inside, the Grand Café Orient maintained the geometry—chairs, lamps, and even coat racks echoed the angular vocabulary.

Three innovations made Cubist architecture in Prague uniquely viable:

- The adaptability of Cubism to traditional urban plots: buildings fit into their historic neighborhoods without erasing context.

- The collaboration between architects and craftsmen: stucco workers, metal smiths, and furniture makers understood how to execute these novel forms.

- The coexistence of Cubism with nationalist goals: it was seen not as foreign import, but as proof of Czech modernity.

This balance of radical form and national application gave Cubist Prague a confidence unmatched elsewhere.

Gočár, Chochol, and the Crystal House

While Gočár led the charge with his early Cubist buildings, his contemporaries brought distinct voices to the movement. Josef Chochol, perhaps the most uncompromising of the group, designed a series of villas in Vyšehrad that remain among the most extreme Cubist structures ever built. His 1913 Kovařovic Villa is a masterclass in fractured form: staircases turn in abrupt diagonals, windows are nested in prismatic recesses, and rooflines slant like shards of glass. The house feels both solid and volatile, as if it had been built from a geological upheaval.

Pavel Janák, meanwhile, combined Cubist principles with a more disciplined rationalism. His theoretical writings positioned Cubism not just as an aesthetic, but as a structural logic: an attempt to unify mass and ornament through tectonic expression. In projects such as the crematorium in Pardubice or the Cubist-style ceramics he designed for industrial production, Janák argued for a total environment. For him, Cubism was not just a style—it was a worldview.

One of the most emblematic buildings of this vision was the Diamond House (Diamantový dům), designed by Emil Králíček in 1912. Though often overlooked, its concave and convex façade, sharp corner details, and interior staircases reflect the Cubist ambition to turn everyday space into visual energy. It was an urban structure that seemed to vibrate with formal intelligence.

Cubist architecture, however, was a short-lived phenomenon. The outbreak of World War I, the economic instability that followed, and the rise of Functionalism in the 1920s all contributed to its decline. But for a brief window, Prague stood alone in treating Cubism as a structural possibility—not just a visual metaphor.

Functionalism Meets the Fractured Form

After 1918, with the founding of Czechoslovakia, modern architecture in Prague took a sharp turn. The demands of a new republic—efficiency, social housing, public infrastructure—required a new architectural language. Functionalism, with its clean lines, flat roofs, and glass-and-concrete materials, supplanted Cubism as the dominant paradigm.

Yet Cubism never disappeared entirely. In fact, it mutated. A short-lived but significant movement known as Rondocubism—or National Style—emerged in the early 1920s. Architects such as Bohumil Hübschmann and Josef Gočár began integrating rounded forms, Czech folkloric motifs, and patriotic colors into their designs. The result was a kind of post-Cubist modernism that gestured back toward the folk revival of the 19th century while looking forward to industrial clarity.

Examples include the Legiobanka Building by Gočár (1923), where geometric ornamentation coexists with sculptural reliefs of legionnaires and historical motifs. The building, though monumental, retains Cubist DNA in its articulation and decorative logic. It is a national modernism—not utopian, but grounded.

The dialogue between Cubism and Functionalism was not hostile. Many of the same architects moved fluidly between the styles, treating each as a toolkit rather than an ideology. The Czech approach to modernism, unlike the doctrinaire purity of Le Corbusier or the Bauhaus, remained plural, adaptive, and locally inflected.

Even as glass towers rose in other European capitals, Prague held on to its fractured edges. Cubism, though eclipsed, had left a residue in the city’s imagination: an awareness that modernity could be expressive, that structure could be symbolic, and that the avant-garde need not erase place.

Today, Prague remains the only city where Cubism is not just a style of painting, but a walkable experience. Its Cubist houses, staircases, lamp posts, and cafés are not museum pieces—they are part of the urban pulse. The city made geometry into poetry, and in doing so, created a modernism all its own.

Surrealism, Dissent, and the Underground Image

By the mid-20th century, Prague had experienced waves of aesthetic transformation—Gothic splendor, Baroque power, National Revival idealism, Cubist radicalism—but none prepared it for the surreal inversion that followed. As political repression tightened under successive regimes, especially during the Communist period, Prague’s artists increasingly turned inward, downward, and obliquely outward. They cultivated a culture of symbols, shadows, and subversion. Surrealism, already latent in the city’s mythic texture, became a lifeline—not just an aesthetic, but a strategy. And with it came a new kind of image: coded, ironic, obsessive, and often dangerous.

Toyen, Štyrský, and the Poetics of Obsession

Prague’s relationship with Surrealism was neither imported nor belated—it was indigenous. Long before the official Czech Surrealist Group formed in the 1930s, the seeds had been sown in the work of artists who found modernist formalism insufficient to express the turbulence beneath the surface. Chief among them were Jindřich Štyrský and Marie Čermínová, better known as Toyen.

Toyen, a name adopted to reject gender categories and traditional authorship, emerged as one of the most distinctive voices in European Surrealism. Working first with Štyrský in a style they called Artificialism—a private, atmospheric idiom of texture and suggestion—Toyen eventually moved into fully Surrealist terrain: dreamscapes rendered with forensic precision, erotic motifs rendered in ghostly abstraction, war horrors transmuted into intimate allegory.

Her wartime works, especially during the Nazi occupation, carry a quiet fury. In The Shooting Range series, grotesque dolls, fragmented limbs, and anatomical diagrams appear against blank, ominous fields. These are not illustrations of violence; they are psychological evidence of its aftermath. Toyen’s art is often mute but never silent. It hums with dread, desire, and defiance.

Štyrský, for his part, produced erotic collages, melancholic cityscapes, and enigmatic texts that resisted linear reading. His photomontages and illustrated journals anticipated later conceptual strategies. Together, he and Toyen helped build a Surrealism that was not Parisian fantasy, but Czech metaphysics—fueled by Kafka’s claustrophobia, Hlaváček’s symbolism, and the gothic architecture of Prague itself.

Key characteristics distinguished Prague Surrealism from its Western counterparts:

- A stronger sense of silence and spatial anxiety—empty rooms, abandoned objects, disrupted scale.

- A recurring use of erotic symbolism as psychological code, often filtered through a cool, almost forensic distance.

- A merging of literature and image—many artists were also poets, translators, and editors, treating image-making as part of a larger symbolic economy.

This visual language of dream and resistance would become a template for the decades ahead, especially under the pressures of authoritarian rule.

Prague Spring and the Photomontage Weapon

The brief period of liberalization known as the Prague Spring (1968) offered a momentary thaw in cultural repression. Artists, writers, and filmmakers seized the opportunity to reconnect with Western avant-gardes and reimagine socialist aesthetics outside the bounds of state kitsch. But the Soviet invasion in August 1968 crushed these hopes—and with them, any illusion that art could proceed innocently.

Visual artists responded not with propaganda, but with subversion. Photomontage, a medium long used for political commentary, became a favored weapon. Karel Teige, though deceased by then, had pioneered the method in the 1930s; now, a new generation revived it with sharper irony and darker tone.

Jan Švankmajer, a key figure of the Czech Surrealist Group in its later phase, moved fluidly between collage, sculpture, and stop-motion film. His animations—such as Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) and Alice (1988)—used found objects, puppets, and disassembled food to tell stories of repression, recursion, and psychological fragmentation. His work was Surrealism under surveillance: grotesque, anti-rhetorical, and full of mute defiance.

Photographers like Václav Chochola and Emila Medková, working in monochrome, created images of urban decay and metaphysical unease: walls that seemed to weep, doors without buildings, wounds in the city’s skin. Their images were not overtly political, but they carried a mood of suffocation and coded memory. The city became a haunted archive.

Underground exhibitions, known as bytové výstavy (apartment shows), took place in private homes. Art was smuggled, whispered, and passed hand to hand. The image no longer functioned in the public sphere; it had retreated to the margins, where its power was paradoxically amplified.

The Charter 77 Generation and Visual Irony

The normalization period that followed the Soviet crackdown saw a deepening of state censorship. Artists who refused to conform were blacklisted, their work prohibited from galleries and official publications. Out of this cultural quarantine, a new generation of dissident artists emerged—less romantic, more ironic, and often brutally self-aware.

Signatories of Charter 77, the human rights manifesto issued in January 1977, included many artists who would form the nucleus of an unofficial, alternative culture. Their visual work tended toward conceptual interventions, absurdist gestures, and documentary subversion. These were not cries for freedom, but diagnostic images of confinement.

David Černý, though younger and more associated with the post-Communist era, inherits this sensibility. His sculpture Entropa (2009), installed in the EU headquarters in Brussels, caricatured each member state with brutal stereotypes—Germany as highways, France on strike, Bulgaria as a squat toilet. While playful, it channeled the Czech tradition of institutional mockery and surreal provocation.

Even earlier, in the 1980s, artists such as Jiří David and Magdalena Jetelová staged clandestine performances, installations, and spatial interventions. Jetelová’s Place (1986), a massive wooden chair installed in the English countryside, and later her laser text projects—ephemeral words inscribed across cityscapes—drew from both the dissident toolkit and the legacy of Prague’s symbolic precision.

Visual irony became a mode of survival. It allowed artists to critique power without slogans, to mourn without elegy, and to resist without martyrdom. The image was no longer a statement—it was a riddle, a joke, a wound with a caption.

By the time the Velvet Revolution arrived in 1989, Prague’s underground art world had already built a dense network of images, ideas, and tactics. Its visual culture had survived by turning inward, by building symbols like bunkers and whispering from the cracks. Surrealism, collage, photomontage, conceptual games—these were not just styles, but lifelines.

The city’s images had been censored, but never erased. They had been pushed into closets, burned into negatives, etched into celluloid, memorized in silence. And when the walls came down, they poured outward—not with vengeance, but with the strange, stuttering poetry of survival.

Post-Communist Reckonings: Memory, Ruin, and Renewal

The Velvet Revolution of 1989 did not merely liberate Prague politically—it triggered a reckoning with the city’s visual memory. Freed from the ideological demands of both Soviet orthodoxy and underground resistance, Prague’s artists, architects, and curators entered a phase of radical introspection. What should be remembered? What should be rebuilt, erased, or exposed? In the decades that followed, Prague became a city of contested symbols, improvised monuments, and ironized nostalgia. The ruin became an aesthetic category, and the past—a layered, unstable archive—became the city’s most charged artistic material.

Graffiti, Ghosts, and the Velvet Wall

In the early days after 1989, Prague’s visual culture exploded with urgency and improvisation. The city’s walls, once carefully monitored, became surfaces for expression. Posters, graffiti, and stenciled slogans bloomed almost overnight. Among the most iconic sites of this spontaneous reclamation was the so-called Lennon Wall near the French Embassy—a public wall that, beginning in the 1980s, had already hosted layers of Beatles lyrics, anti-regime slogans, and makeshift shrines. After the revolution, it transformed into a palimpsest of hope, chaos, and unresolved grief.

The Lennon Wall functioned as both memorial and protest, art space and tourist magnet. Layers of paint were constantly added, covered, and revealed again. It became a living object—always unfinished, always in negotiation. For Prague’s younger artists, it was also a site of frustration: its symbolism risked ossification, its commodification undermined its original radicalism.

More enduring, perhaps, were the ephemeral interventions that briefly surfaced and then vanished—acts of drawing, projection, and occupation that refused to be historicized. Artists like Jiří Kovanda and Krištof Kintera worked with disruption rather than assertion. Kovanda, known for his “invisible” performances under the regime, continued his practice of minor transgressions—rearranging objects, interrupting spaces, unsettling expectations.

These interventions marked a shift from monumentality to intimacy. In a city laden with stone saints and equestrian heroes, the new art sought smaller openings—places where the past could be prodded rather than staged.

Three visual gestures became emblematic of the early post-Communist moment:

- The restoration or partial exposure of Communist-era signage and architecture, now seen through a double lens of nostalgia and critique.

- The use of projection and video mapping to animate historical facades with ghostly, shifting imagery.

- The insertion of subtle commemorative markers—stumbling stones, nameplates, or sidewalk engravings—into everyday infrastructure.

These were not grand symbols. They were visual murmurs, attempts to rethread the past into the city’s living surface.

David Černý and the Politics of Public Art

Perhaps no artist has shaped Prague’s post-1989 public image more provocatively than David Černý. Irreverent, confrontational, and often vulgar, Černý has made a career of goading both local and international audiences into uncomfortable laughter. His sculptures litter the city like political landmines—part visual pun, part institutional provocation.

His 1991 work Pink Tank, in which he painted a Soviet-era tank bright pink and added a raised middle finger, remains a foundational act of post-Communist satire. Though briefly arrested for the gesture, Černý was celebrated by many as embodying the spirit of the Velvet Revolution—a refusal to sanctify the past, a will to make mockery into moral weapon.

Since then, his projects have grown in scale and ambition. Babies, a series of grotesque infant sculptures with barcode faces, now crawl up the Žižkov Television Tower. His rotating bust of Kafka, composed of mirrored layers, presents a kind of kinetic absurdity: a literary mind in perpetual reassembly. Even when commissioned, Černý’s works rarely flatter; they deride, disturb, and destabilize.

His 2009 installation Entropa for the EU Presidency—a massive collage of European stereotypes placed within the EU headquarters—exemplifies his brand of institutional mischief. The piece triggered diplomatic protests and debates about national identity, artistic license, and European unity. It was not elegant, but it was effective: it reminded viewers that symbols are always contested, and public space is never neutral.

Černý’s critics argue that his work flirts too often with spectacle and avoids moral depth. But his defenders note that in a city where history is often monumentalized into piety, his derision offers a necessary counterweight. He forces the city to ask what it is willing to laugh at—and what it isn’t.

Nostalgia, Museums, and the Archive of Irony

As the 1990s gave way to the 2000s, Prague entered a more institutional phase of its post-Communist aesthetic: museums, archives, and state-sponsored memorials proliferated. But even these structures bore the marks of aesthetic ambivalence. Should the past be preserved or deconstructed? Should memory comfort or provoke?

The Museum of Communism, opened in 2001 above a McDonald’s and a casino, became a symbol of this strange collision. Its exhibition, filled with propaganda posters, wax mannequins, and kitsch artifacts, tried to walk the line between documentation and spectacle. For some, it offered necessary confrontation; for others, it risked trivialization. The juxtaposition of horror and humor—bread lines and neon signage—made it hard to tell if one was in a shrine or a parody.

More serious efforts emerged as well. The DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, opened in 2008 in a repurposed factory, quickly became a hub for conceptual and socially engaged art. Its exhibitions often focus on memory, disinformation, and post-totalitarian anxiety. Here, artists interrogate not just the past, but the mechanisms by which we frame and forget it.

Photography, too, entered a new phase. Exhibitions revisiting the work of dissident photographers—like Libuše Jarcovjáková’s nocturnal images of queer and underground life—reframed the late socialist period not as an era of silence, but of coded vitality. These images, once marginal, became central to the city’s memory culture.

Even the city’s ruins began to be re-evaluated. Former bunkers, factories, and surveillance stations became galleries, theaters, or simply left as open scars. Prague did not sanitize its decay—it began to curate it.

Post-Communist Prague is not a city that forgets easily. It is a city where every corner contains a contested layer, every sculpture a debate, every restoration a choice. The reckoning with memory—still ongoing—has produced a rich, often ironic visual culture. It is a culture skeptical of monumentality, alert to contradiction, and attuned to the aesthetics of absence.

The ruin is no longer something to fix, but something to read. The past is not something to restore, but something to haunt with precision. And the future? It remains, fittingly for Prague, a mirrored surface: fractured, reflective, and always shifting.

Contemporary Prague: Digital Experiment, Global Frame

In the 21st century, Prague’s visual culture exists in a paradox. It is at once deeply rooted in its historical sediment and increasingly untethered by the demands of global capitalism, digital circulation, and aesthetic pluralism. Artists now operate within overlapping systems—public institutions, online platforms, activist networks, commercial galleries, and algorithmic economies. The past is never far behind, but it no longer dictates form. Instead, memory, space, and national identity are refracted through new technologies and new modes of engagement. Contemporary art in Prague is not a unified movement—it is a zone of experimentation, irony, preservation, and acceleration.

AI, NFTs, and the New Bohemian Circuit

Over the last decade, digital media has reshaped the production, distribution, and reception of art in Prague. While traditional forms—painting, sculpture, photography—remain robust, the digital has become both a tool and a subject. Artists manipulate datasets, train machine learning models, mint NFTs, and stage virtual exhibitions. This is not novelty for novelty’s sake; rather, it reflects a longstanding Czech fascination with systems, codes, and absurdities.

The influence of Czech conceptualism—especially the legacy of Jiří Kolář, Milan Knížák, and the broader Fluxus-affiliated scene—remains strong in this context. Today’s digital artists often channel this sensibility: low-budget satire, algorithmic collage, and self-effacing criticality. Where the West’s digital art sometimes leans toward grandiosity or techno-optimism, Prague’s version tends to be anti-heroic, even melancholic.

NFT art arrived in Prague not as a speculative mania, but as an ambivalent experiment. Platforms like Tezos and Ethereum host Czech creators who produce digital ephemera infused with local themes—ghosts of Kafka, pixelated Cubism, VR reconstructions of vanished architecture. These works rarely command top auction prices, but they circulate widely within niche, literate communities.

Artists such as Janek Rous and Magdalena Jadwiga Härtelová explore digital form in relation to language and ritual. Their works combine video, sound, and code into layered installations that evoke both folkloric enchantment and data anxiety. They do not treat the digital as future—they treat it as medium.

Prague’s art schools—particularly the Academy of Fine Arts and the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design—now foster this hybridity. Young artists are trained not only in studio craft, but in curatorial practice, web-based production, and critical theory. The new Bohemia is dispersed, but it speaks fluently in pixels and projections.

The Biennale’s Shifting Language

The Prague Biennale, launched in 2003, attempted to position the city as a hub of Central European contemporary art. In its early editions, the Biennale emphasized post-Communist transformation, new media, and the reconfiguration of the “East” as both aesthetic and geopolitical category. Its curatorial language was ambitious—often grand, occasionally opaque—and the results were uneven. Still, it provided a platform for Czech artists to be seen in international dialogue.

Over time, the Biennale has fluctuated between local engagement and global ambition. Some editions have foregrounded ecological art, queer archives, and anti-authoritarian strategies. Others have veered toward the commercially polished or curatorially incoherent. But its existence—despite funding struggles and organizational resets—testifies to Prague’s ongoing desire to situate itself within global flows while retaining a distinctive visual cadence.